Taiwanese Hokkien/Southern Min

Miao-Ling Hsieh(謝妙玲)

The Handbook of Chinese Linguistics

1. TSM vs. MD in general

2. Word order

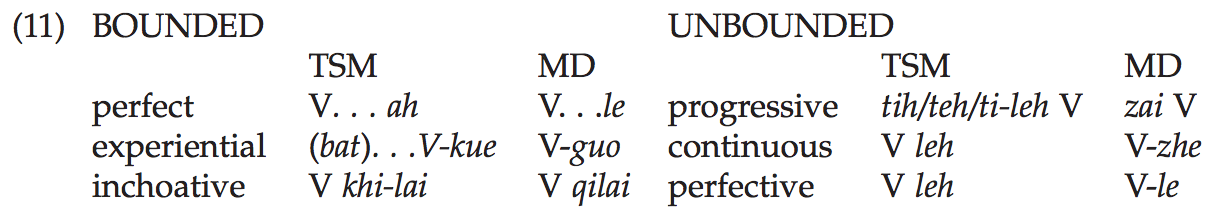

3. Aspect/phase markers

4. Causative/passive/unaccusative sentences

5. Negative question particles

6. Nominal domains

7. Conclusions

TSM vs. MD in general

1. SVO order, topicalization, focalization(focus)

2. Aspect/phase markers(ah、kue、khi-lai、ti-leh, 了、過、著)

3. Productive in verb compounding

4. Sentence-final particles(bo、be、m, 嗎、吧)

5. Classifier(measure word) with numeral

6. TSM is generally characterized to be more topic-prominent and analytic compared to MD

Word Order

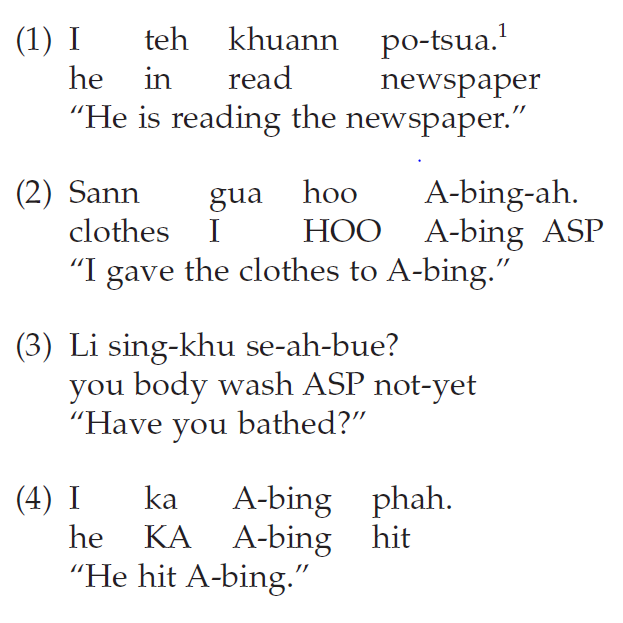

(1)Typically SVO

(2)OSV: Pre-verbal object is allowed, but is marked(有標) The object is topicalized

(3)SOV: Topicalization, usually associated with focus

(4)Affectee theta marker - ka

Word Order - Topics, Focuses

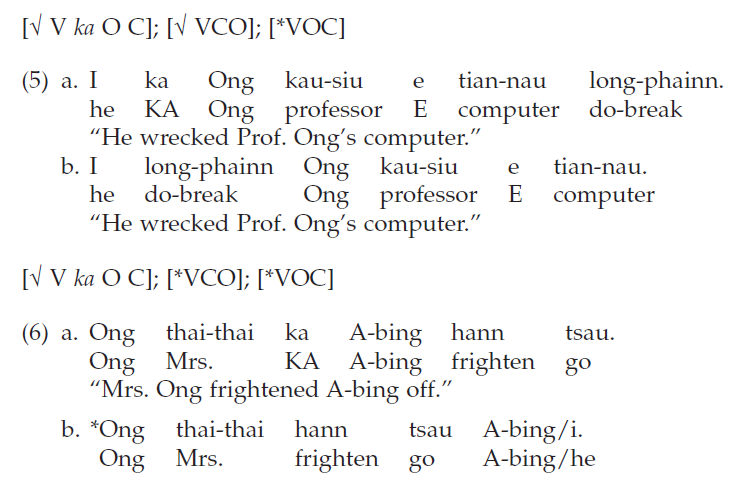

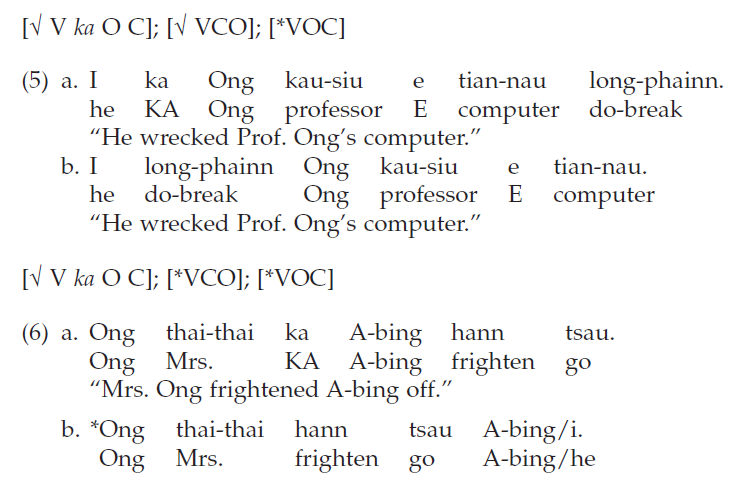

Verb complex: V + aspect/phase marker or a resultative/directional/potential complement e.g. 挵歹, 食了, 嚇走

The tendency for an object to be preposed for simplex verbs and verb complexes(VCs)

Word Order - Topics, Focuses

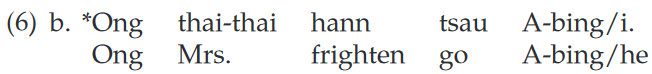

Long-phainn is a compound word, hann tsau is not.

The latter forms serial verb construction(連動結構)

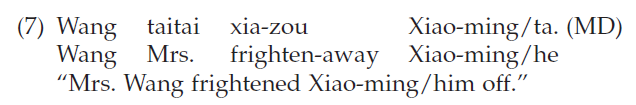

Word Order - Topics, Focuses

Most VCs in TSM don't take a post-verbal object while MD generally allows:

Word Order - Verb complexes

What decides whether a VC is a word?

Idiosyncratic(癖義) or rule-governed?

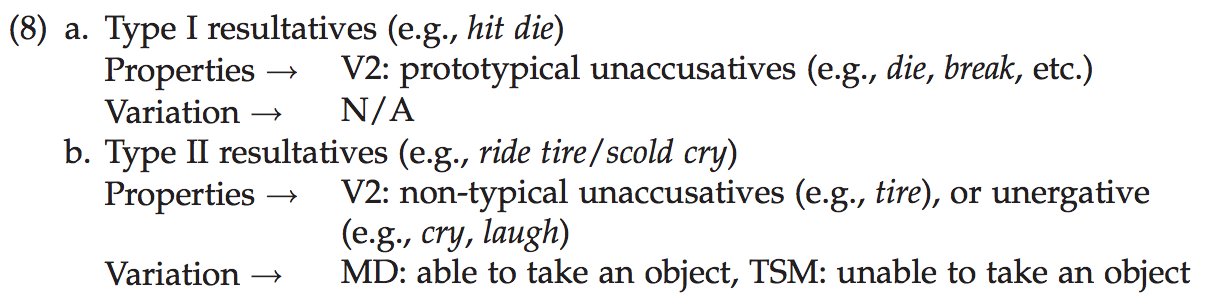

Wang, C. A.(2010)

Word Order - Verb complexes

Some problems: Not all unaccusative verbs belong to his Type I and not all unergative verbs behave like his Type II

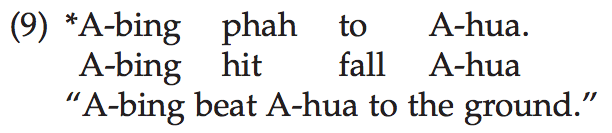

to : Takes an internal argument but no external argument, but a VC with such a C does not precede its object.

Word Order - Iann/Su/Pai

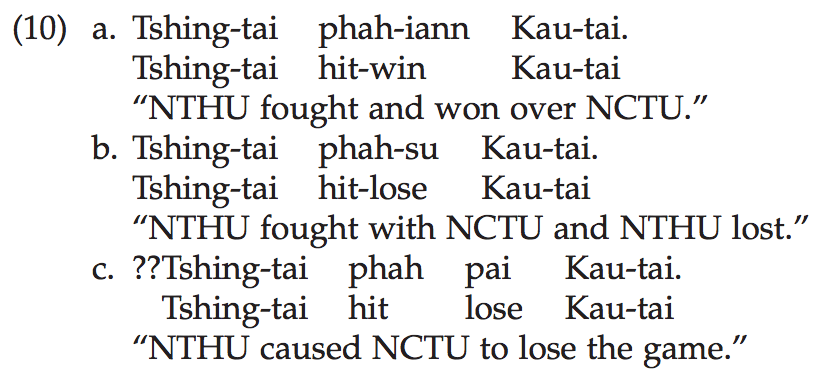

If iann/su and pai are taken to be unergative and unaccusative respectively, what Wang predicts is not borne out.

Lien, C. (2002)

If Wang's analysis were on the right track, there would be variation between TSM and MD for the VCs in (10a,b) because they belong to Type II and the VC in (10c) would be acceptable in both TSM and MD because it is Type I. More research in the future will thus be needed for the analysis of such data.

Aspect markers

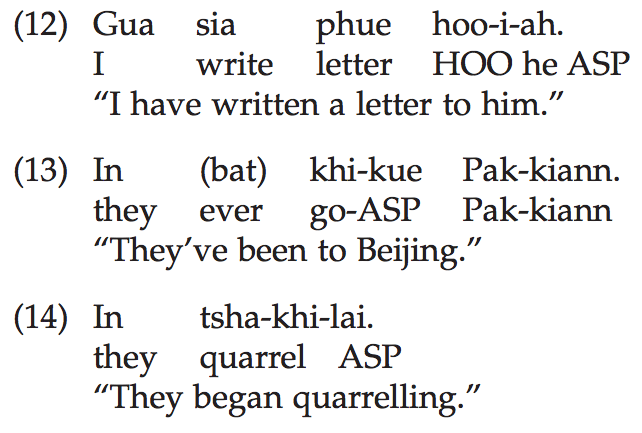

Aspect markers - ah

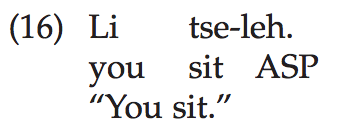

The perfect ah has to occur at a clause-final position.

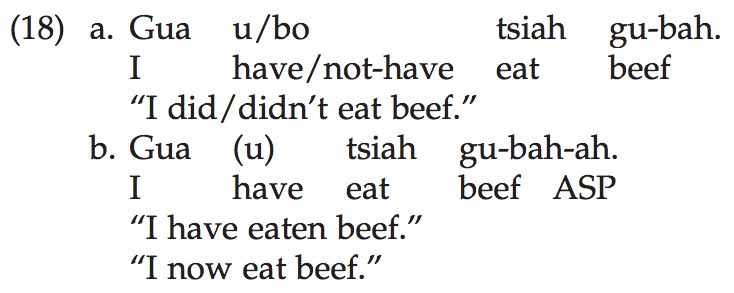

u

A modal marker of emphatic assertion. It is similar to the perfect le(了) in MD

(18b): "I have eaten beef" / "I have started eating and is still eating beef."

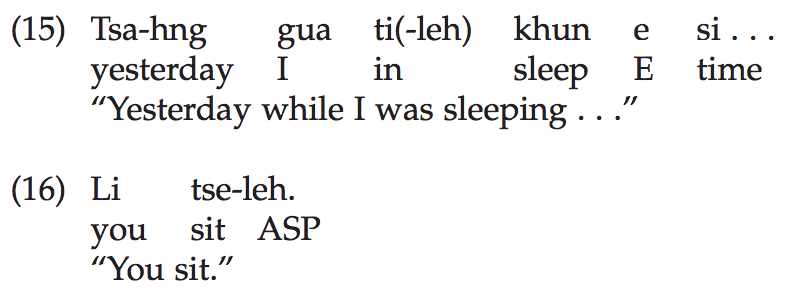

Aspect markers - tih/teh/ti-leh/leh

Relations between tih/teh/ti-leh and leh (Yang, H., 1992) :

Continuous leh is a variant of the pre-verbal Tih/teh through tone neutralization and the change of the initial at the clause-final position, it can also mark perfectivity.

Aspect markers - leh

The perfective of continuous use may depend on verb types.

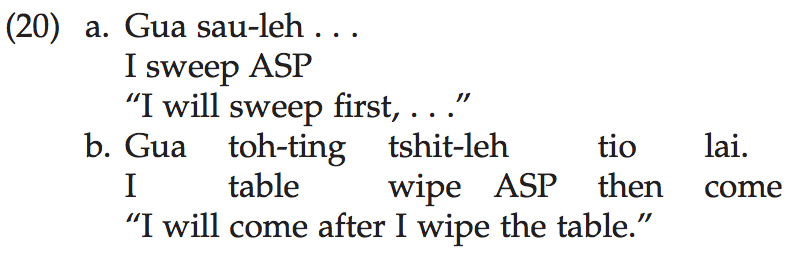

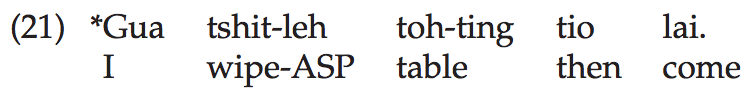

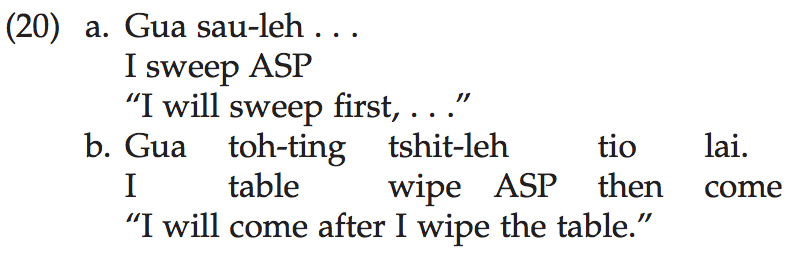

The post-verbal leh has to occur in the clause-final position:

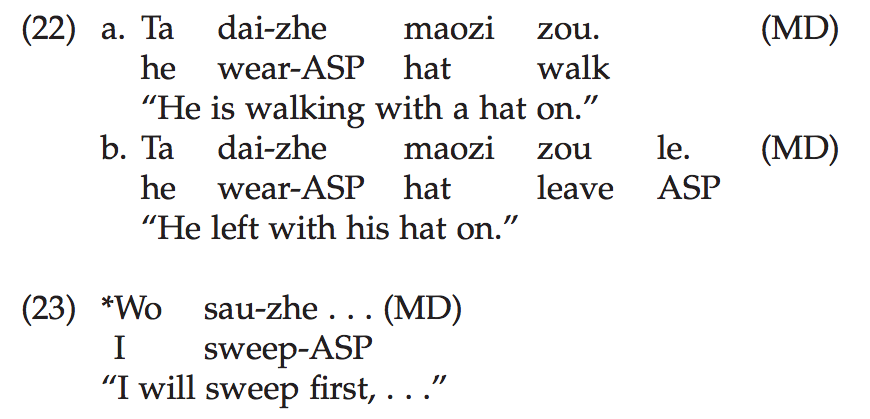

Aspect markers - MD zhe

The continuous marker zhe is a suffix and can only have the continuous use serving as a background marking the manner in which an action is carried out. It does not mark perfectivity.

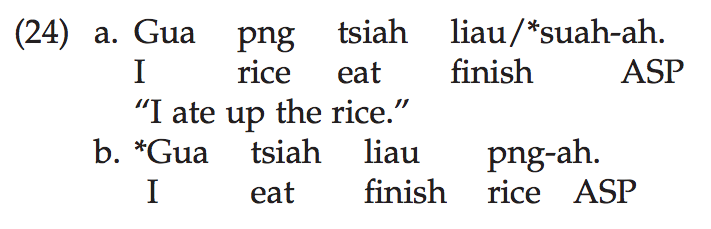

Phase markers - liau/suah

Liau marks the complete consumption of the object of an action.

Suah marks the completion of an action.

Both of them can NOT precede an object.

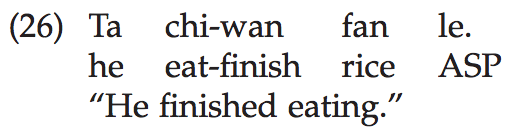

The phase marker wan in MD allows a post-verbal object:

Phase markers - liau/suah

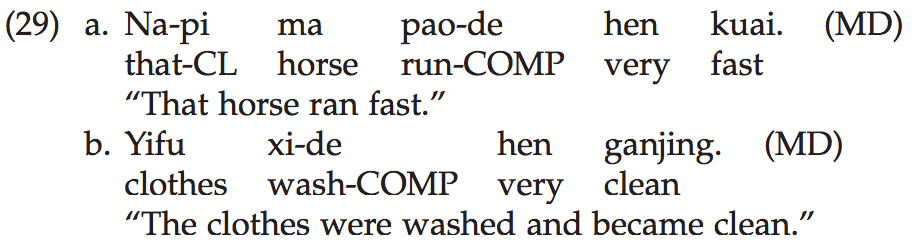

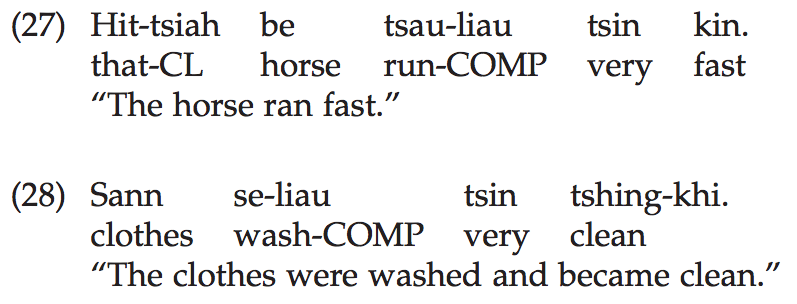

Another difference between liau and wan is that the former can introduce an extent complement (27) or a resultative complement (28), functioning like a complementizer:

It is translated into de in MD:

Phase markers - liau/suah

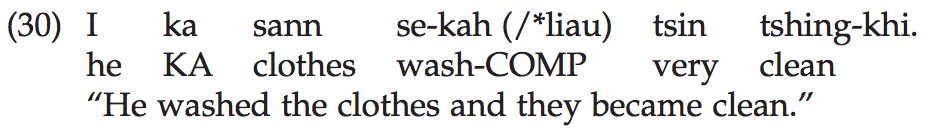

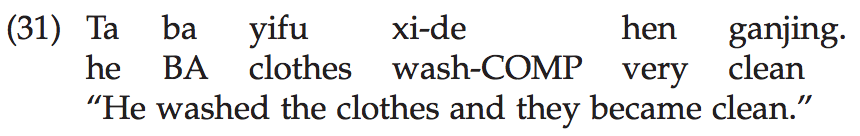

The resultative use in (28) is unaccusative. The subject of (28) is the internal argument. When an external argument is involved, only kah can be used.

No such restriction is found with MD. The same de is used.

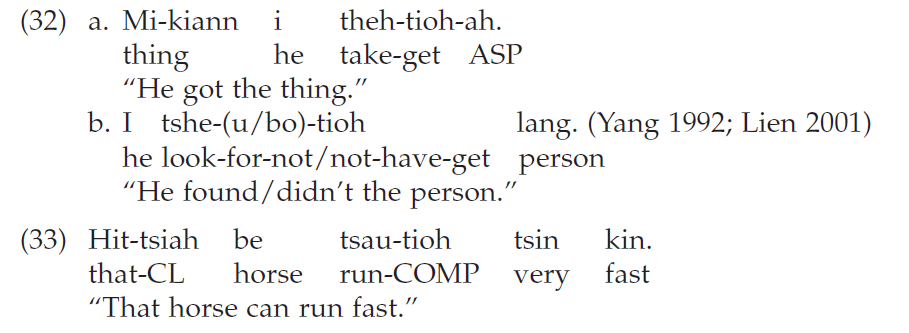

Phase markers - tioh

Tioh is usually translated into dao in MD

Meaning: The attainment of a goal.

V+tioh can take an object even when V and tioh are separated by the modal u/bo

Also, tioh can be used to introduce a complement (33).

Phase markers - tioh

This use of tioh in (33) emphasizes the capability of the horse.

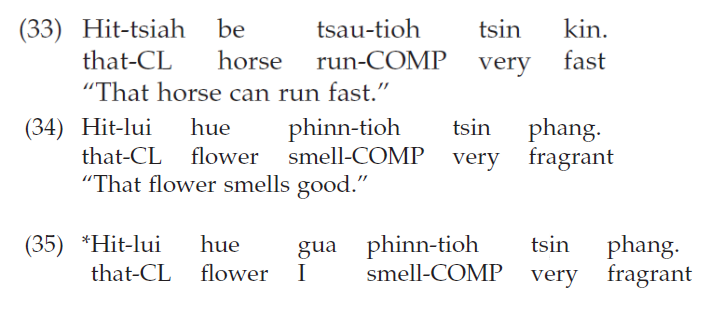

Tioh can also form a middle construction(中間結構) as in (34).

The presence of an external argument is disallowed (35).

中間結構是語言學研究中一種頗有爭議的結構形式。句中動詞具有及物性,以主動形式出現,但是動詞的施事不出現,句子主語由動詞的受事充當。另外,句中有一不可或缺的表示狀態的副詞做狀語。整個結構不表示對動作或事件的陳述,而是對受事主語的某種狀態進行的描述。

From: https://goo.gl/xYivKE

Phase markers

Tioh is the most grammaticalized(語法化) one since it can form a word with a verb and take an object.

Also, compared with MD, TSM employs more complementizers for difference meanings.

Grammaticalize: 意義實在的詞轉化為無實在意義,標示功能的成分的「過程或現象」

From: https://goo.gl/ZYhdkH

Causative/passive/unaccusative sentences

Causatives without hoo

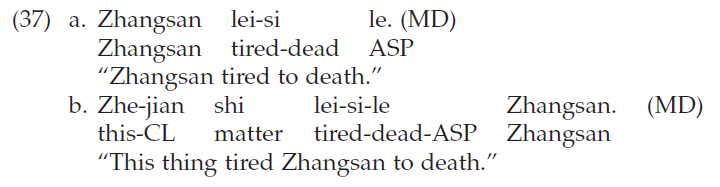

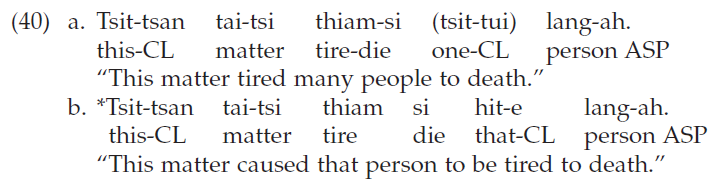

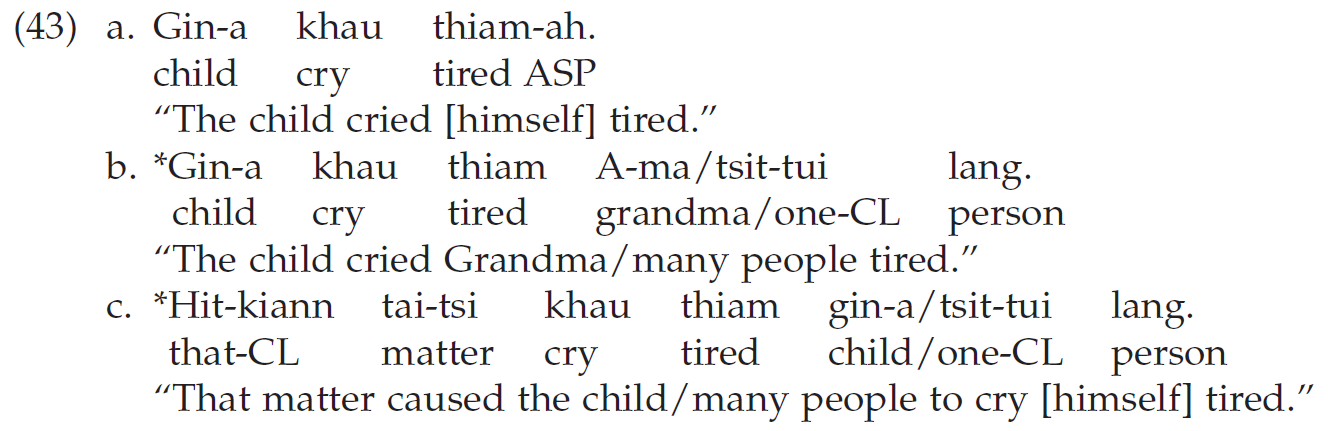

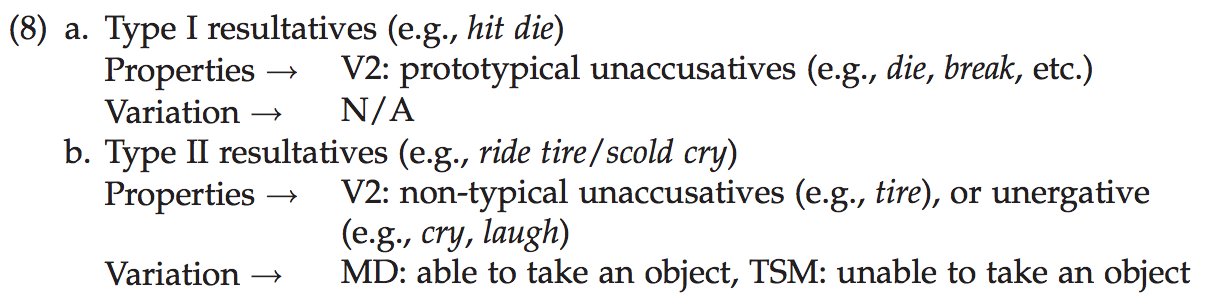

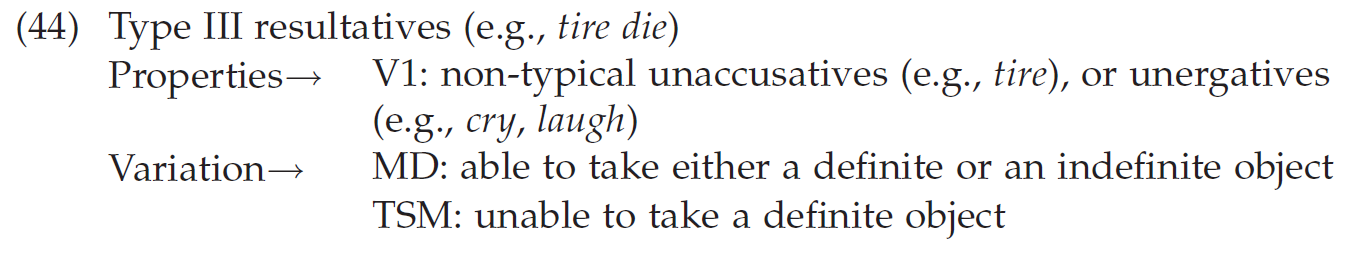

Research in MD shows that two types of causatives involve resultatives(結果式)(e.g., C.-T. Huang 2006).

The first type exhibits the typical unaccusative-causative(非賓格-使動) alternation.

An unaccusative is causativized with the addition of an external Causer argument.

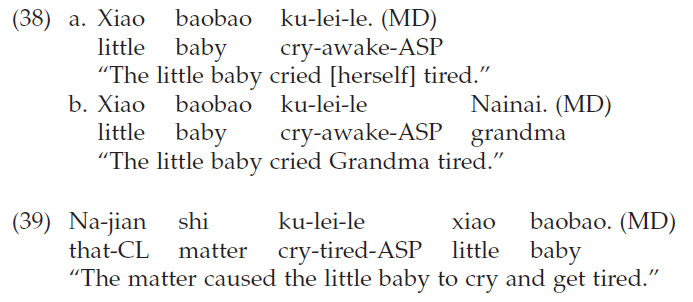

Causatives without hoo

The second type involves an unergative-transitive(非作格-及物) alternation (38), which shows that V1 remains the subject in both the intransitive and transitive version.

Although such resultatives do not have a causative meaning, they can be made causative (39):

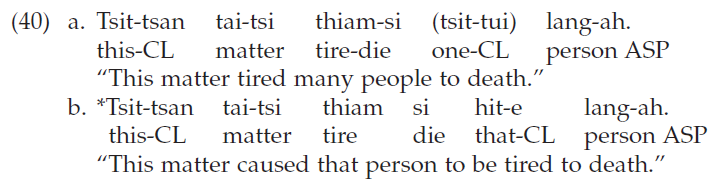

Causatives without hoo

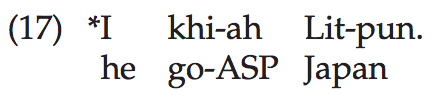

TSM has unaccusative-causatives, but they are restricted.

They can take an indefinite object, but not a definite object:

Causatives without hoo

Despite the fact that TSM has restricted unaccusataive-causatives, it does not have unergative causatives.

Causatives without hoo

No unergative-causatives

Wang, C.A. (2010)

Causatives without hoo

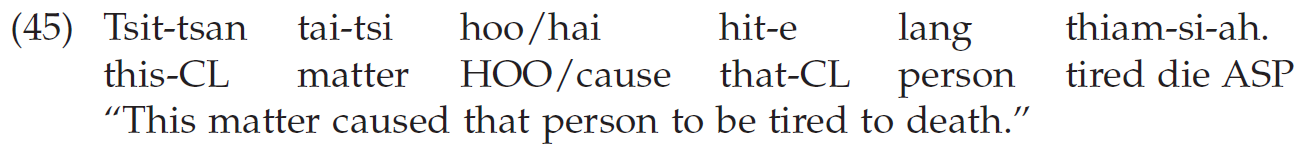

TSM is more analytic than MD because an overt causative marker has to be used for the unaccusative-causative in (40a) when a definite object is used.

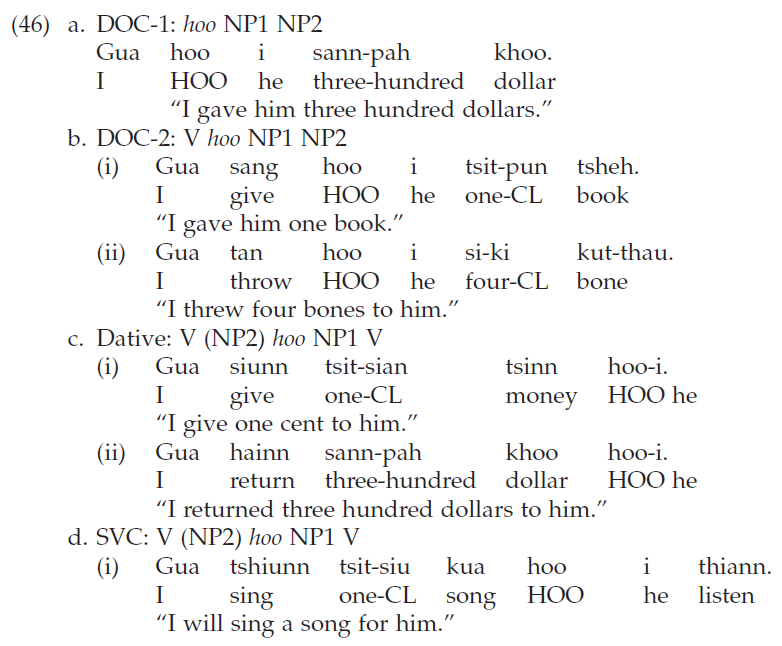

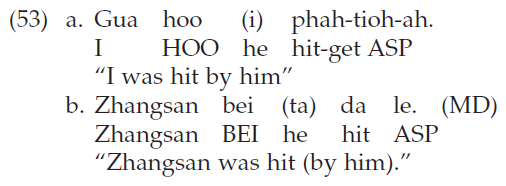

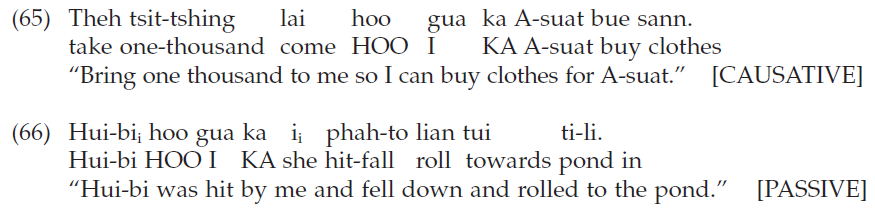

Hoo sentences

There are six patterns and are either causative or passive:

DOC: Double-Object Construction, 雙賓結構

Dative: 與格

SVC: Serial Verb Construction, 連動結構

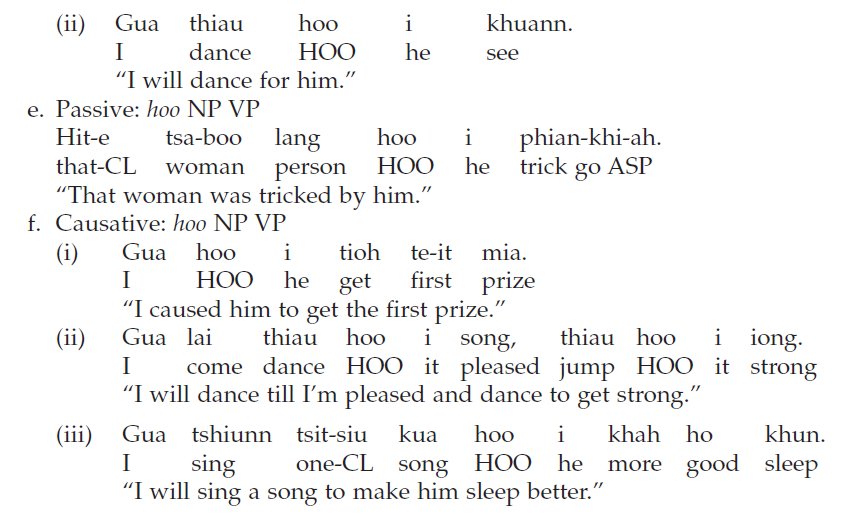

Hoo sentences

Hoo sentences

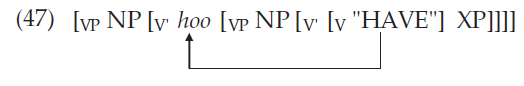

Cheng et al. propose that the two double-object constructions (DOC) in (46a–b) involve a causative hoo. (46bi) means “I caused him to have one book.” In a DOC-2, the embedded “have” can raise and be realized as hoo:

Hoo sentences

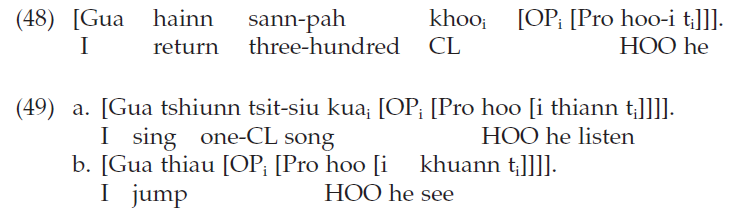

The dative construction in (46c) and the serial verb construction (SVC) in (46d) also involve a causative hoo clause, which predicts on the object in (48) and (49a) or the subject/event argument in (49b).

Hoo sentences

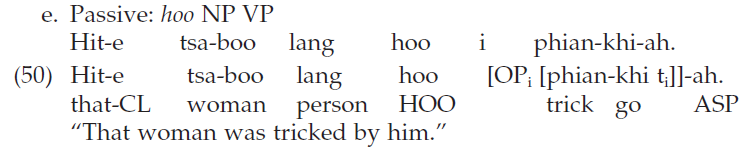

The passive hoo sentence in (46e) involves a NOP (null operator) movement in the embedded clause as follows:

Hoo sentences

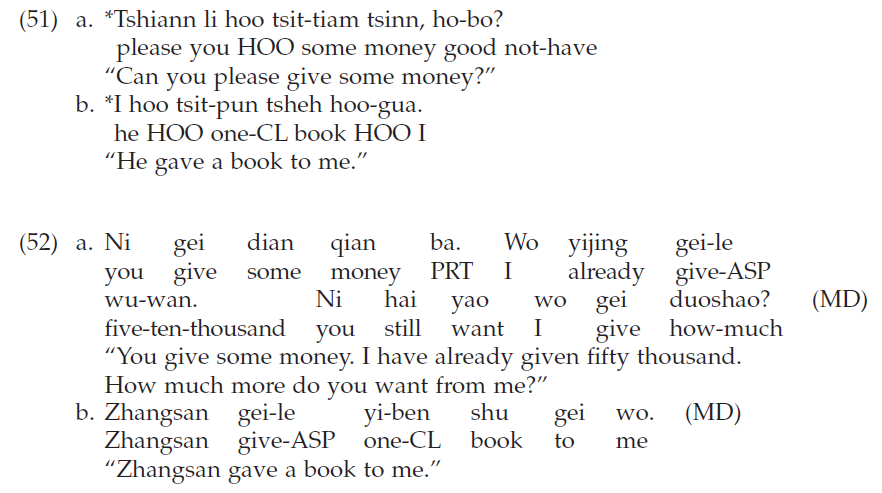

Cheng et al. (1999: 167) show that hoo behaves like a causative verb, unlike its counterpart in MD:

Gei is just like a transitive verb, rather than a ditransitive verb, and (52b) indicates that the use of gei has approached the status of a preposition

Hoo sentences

Hoo must take a human or animate NP shows that it is closer to a ditransitive verb in having a human or animate NP as a recipient.

Two more important conclusions added in C.-T. Huang (1999) are as follows. First, TSM does not have a short passive, unlike MD.

Short passive: passive without an agent

The fact that hoo in the above example has the tone value of the third person singular pronoun, i, supports the analysis that hoo is a contraction(縮合) of hoo plus i and hence a long passive is involved.

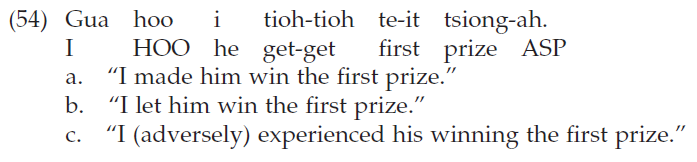

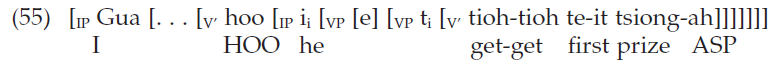

Hoo sentences

A hoo sentence in (54) can be three-way ambiguous with a strong and weak causative reading (“cause” and “let”) and an adversative passive reading.

The adversative reading is also derived by the NOP movement. What is different from the direct passive is that an “outmost” object is introduced.

In (55), [e] can be seen as an object of the VP, whose subject has raised to IP.The outermost object undergoes the NOP movement and is co-indexed(同指標) with the subject gua.

同指標:指涉ê對象相仝

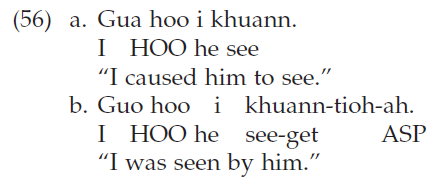

Hoo sentences

Passive hoo is related to the causative hoo through the causative–ergative alternation. That is, the passive meaning is precisely the inchoative/ergative counterpart of the cause reading of causative hoo.

This analysis explains why the passive meaning is possible only with verbs that are accomplishments but not activities, since this is a property of the causative–ergative alternation.

(Cheng et al. (1999) and C.-T. Huang (1999))

(Cheng et al. (1999))

Hoo sentences

Accomplishments and activities differ in boundedness. But in contrast to the remark in Cheng et al., a passive reading is possible when an activity is involved:

To derive a passive reading, what is crucial seems to be the case that the subject of a hoo clause has to be adversatively affected. More discussion of this is given in the next section.

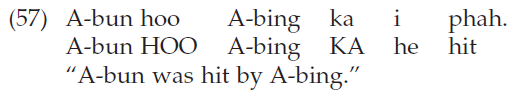

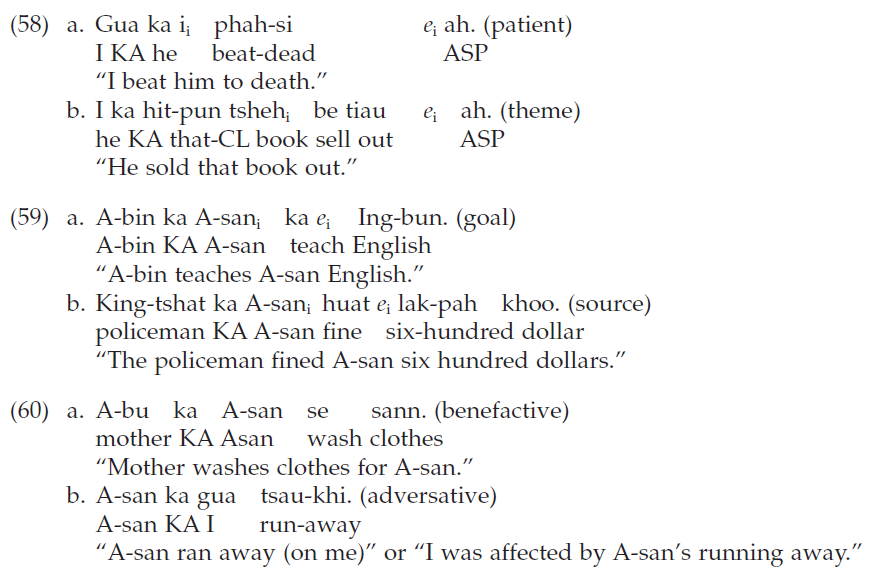

Hoo...ka sentences

It has been observed that ka can introduce many different thematic roles in a pre-verbal position.

Mark a patient

Mark a goal

Mark a theme

Mark a source

Benefactive marker

Adversative marker

↑受惠格

Hoo...ka sentences

light verb(輕動詞): 一些詞匯意義虛無 ,但卻發揮著主要句法功能的動詞

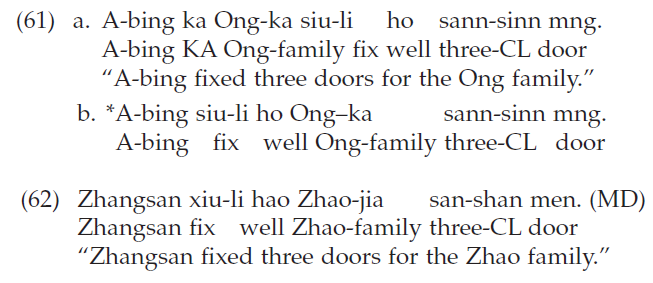

While the low applicative construction in (62) marking the relation between an event and a recipient in MD does not involve an overt marker, its TSM counterpart in (61) has to be overtly marked by ka:

Benefactive ka occurs in a lower position than the malefactive(受害格) ka.

Hoo...ka sentences

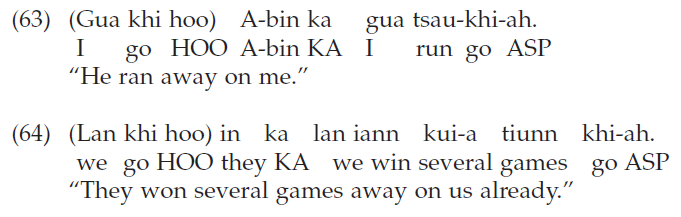

The distinction between the two uses of ka can be made by the use of khi ,which clearly marks adversity. Khi can occur before hoo, immediately after the verb or at the end of a clause

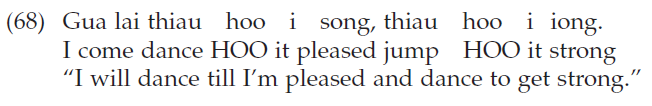

Hoo...ka sentences

Passive and causative reading

The examples in (65) and (66) show that when the argument introduced by ka refers to the same referent with the subject of a hoo sentence, a passive reading is available.

Unaccusative sentences

TSM also has pure unaccusatives (or inchoative), which do not demonstrate a causative alternation and can occur with hoo i to denote adversity. This hoo is obligatorily(強制性的) followed by the pronoun i, which is expletive(虛詞) and non-referential.

The hoo i sequence is analyzed to be an optional adjunct (adjoined to VP) used to denote adversity.

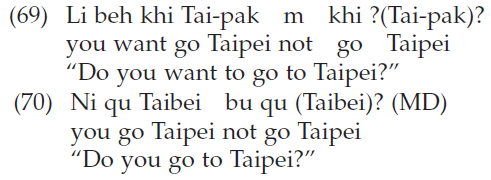

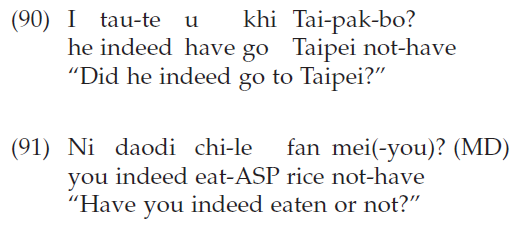

Negative question particles

Question types

Both TSM and MD involve sentence final particles.

Yes–no questions((Q-VP))

Disjunction questions(V(P)-not-V(P))

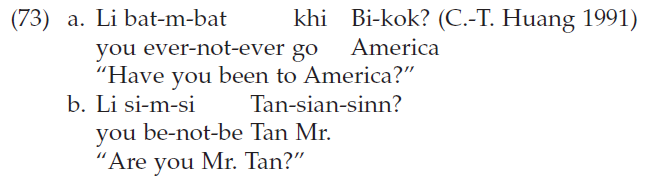

Both TSM and MD share the possibility of VP-not-V(P) forms:

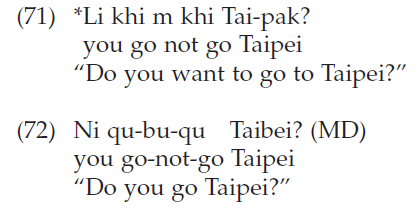

Question types

The VP-not-V form in TSM is somewhat degraded(?).

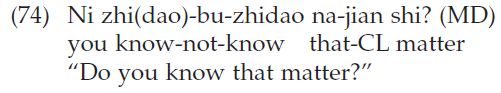

What clearly distinguishes TSM and MD is the V-not-VP type.

It is productive in MD, but unacceptable in TSM in general:

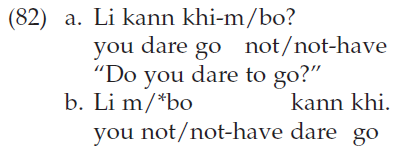

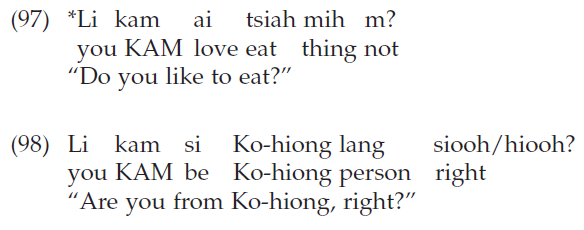

Only a few cases with the V-not-VP form in TSM are acceptable.

Question types

An acceptable V-not-VP form must be m. In addition, m in a V-not-VP form must be non-volitional (非意願), in contrast to the volitional m in (69). In addition to bat and si, only a few verbs can form a V-not-VP question. They include tsai, kann, tioh, bat, ho, thang, khing, and kam-guan, which do not seem to form a natural class(自然詞類?) in any way.

V-not-VP type is quite productive in MD

Question types

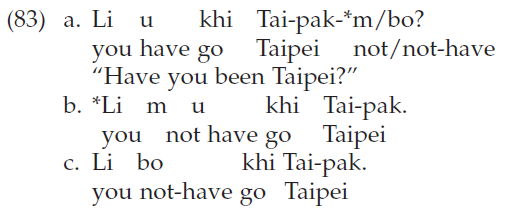

Because of the limited use of the V-not-VP form in TSM, a V-not-VP question in MD is usually translated into a VP-not in TSM, where a negative particle occurs at the sentence-final position. Neg-particles share the same forms with negative markers but receive a neutral tone instead.

TSM:

-m, -bo, -be, -

MD:

bu, mei(-you)

Question types

While the neg-particles in MD respect the agreement between the negative marker and verb/aspect, not all the neg-particles in TSM do. For example, while m observes the agreement, bo seems to be freer (with some exceptions such as si, Audrey Li, pers. comm.).

The neg-particles in both TSM and MD do not occur with a negative clause.

Analyses of negative question particles

They are neutral with respect to the answers expected of an addressee and cannot accept short answers like henn in TSM and shide in MD.

Analyses of negative question particles

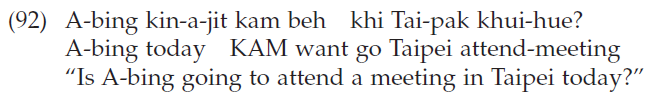

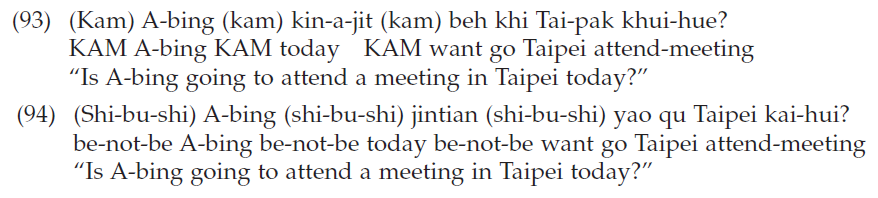

This type of question, that is the Q-VP type, is found in TSM but is not attested in MD.

Kam is the form closest to the yes–no question marker ma(MD), which is modality-free and can mark a rhetorical question(反問句).

The element that immediately follows kam has to be the focus , just like shi-bu-shi in MD

Kam, predicate-initial(謂語前置) question marker

Analyses of negative question particles

When placed in a pre-subject position, kam can only ask about the subject.

Analyses of negative question particles

M behaves differently from other true candidates of tag questions. That is, while m cannot occur with kam, other candidates of tag questions can:

The differences between TSM and MD in neg-particles show that TSM employs more neg-particles and they may occur in different positions, and more elaborate structure will be needed.

Nominal Domains

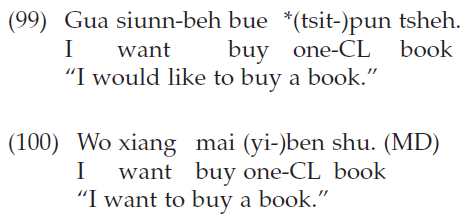

Like MD, TSM nouns cannot be counted without a classifier But while MD allows indefinite CL-NPs when the numeral is yi , TSM does not allow empty numerals

Nominal Domains

Cheng and Sybesma (2005) argue that classifier languages, having no indefinite article(冠詞), derive their indefinites based on definites, with the latter involving a Classifier Phrase and the former a Numeral Phrase on top of the Classifier Phrase. If this analysis is on the right track, this means the distinction between definites and indefinites has to be overtly marked in TSM when a classifier is involved.

Another differences between TSM and MD in neg-particles show that TSM employs more neg-particles and they may occur in different positions, and more elaborate structure will be needed.

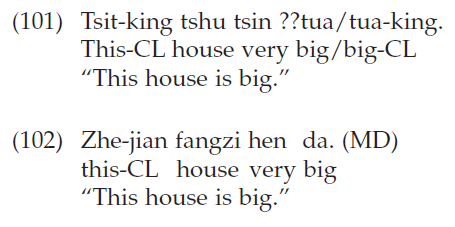

Nominal Domains

Other adjectives – se, tshim, tshian, tng, and khuah – behave the same. The classifiers are analyzed to be part of compound adjectives, serving as dimension markers.

Finally, another difference between TSM and MD in noun phrases is the modifier marker e in TSM and its counterpart de in MD.

The three differences between TSM and MD in nominal domains suggest that TSM may be more analytic in not allowing the omission of the numeral “one”.

Conclusions

-

TSM may be more analytic than MD

in allowing more verb complexes to be analyzed as compound words and to take post-verbal objects. - TSM employs pre-verbal adverbs, auxiliary verbs, and clause-final particles to encode aspect, while MD mainly uses suffixes for marking aspect. As far as phase markers are concerned, among the three TSM phase markers discussed, that is,

liau ,suah tioh , the first two cannot form a word with the verb, unlike MD.Tioh is the only exception.

Conclusions

- It is more difficult for TSM to have causatives without overt marking, unlike MD. Also, for a low benefactive applicative construction, TSM has to mark it with an overt marker, that is the benefactive ka, while no overt marking is required for MD. Moreover, hoo i in TSM instead of hoo by itself is grammaticalized.

- TSM has more neg-particles and they may occur in different syntactic positions. More elaborate structure is needed for TSM.

- In TSM, the numeral “one” can never be omitted, but the deletion is possible in MD when it occurs in an indefinite NP. Also, some adjectives in TSM, not in MD, require the presence of a classifier for marking dimension. Moreover, unlike MD, TSM allows two modifier markers to occur together.

Conclusions

More research will be required for the test of analyticity and for more revealing differences between the two dialects and others.