Local and regional democracy

in European politics

Based on paper of Frank Hendriks, Anders Lidström and John Loughlin

Subnational governments

[Local governments, local governance]

What is it?

Why is it s important?

Subnational governments

- Subnational governments are generally underestimated as levels of government in the European context.

- There are almost 100,000 democratically elected units of local and regional selfgovernment in the EU;

- not only do these units serve important functions in the everyday life of European citizens, but they also play a key role in the implementation and legitimation of national and European policies.

- Local and regional governments are the units of democracy closest to the people.

Subnational governments

- Most subnational governments in Europe have deep historical roots, often based on traditions of local rule, self-organization or city government dating back to the Middle Ages.

- With the arrival of the modern state from the sixteenth century onwards, these systems of government were absorbed into, and dominated by, what became the central governments of unitary states or the sub-federal units of federal states.

Subnational governments

- Nevertheless, some of their traits have persisted over the years and are still visible in the ways in which subnational governments are organized.

- This would suggest that local and regional governments are subject to strong path-dependencies and institutional resistance, as suggested by historical institutionalism. This is also reflected in how democracy is coordinated at these levels.

Subnational governments

- However, the key importance here are changes in the situations of nation-states themselves.

- Nation-states are still generally the principal actors within systems of governance, but they have become subject to pressures from above – from globalization and, in Europe, the constraints of European integration – as well as from below, as regions and local authorities have mobilized, becoming less dependent on and subject to their respective national governments.

Subnational governments

Text

Subnational governments

The idea of neomedievalism (new -, neo-)

It is also conceivable that sovereign states might disappear and be replaced not by a world government but by a modern and secular equivalent of the kind of universal political organisation that existed in Western Christendom in the Middle Ages.

In that system no ruler or state was sovereign in the sense of being supreme over a given territory and a given segment of the Christian population; each had to share authority with vassals beneath, and with the Pope and (in Germany and Italy) the Holy Roman Emperor above.

The universal political order of Western Christendom represents an alternative to the system of states which does not yet embody universal government.

Bull H., The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics, London 2002, s. 245-246.

Subnational governments

- However, the key importance here are changes in the situations of nation-states themselves.

- Nation-states are still generally the principal actors within systems of governance, but they have become subject to pressures from above – from globalization and, in Europe, the constraints of European integration – as well as from below, as regions and local authorities have mobilized, becoming less dependent on and subject to their respective national governments.

Method

- We will use two main sets of theoretical constructs in order to analyse the patterns of European

local and regional democracy. - Countries with various systems of local and regional government will be grouped together according to similarities in their organization, their main functions

and their relationship with the state. - These patterns are largely path-dependent and are based on the specific state traditions to which they belong. In addition, we will identify four different models of democracy that will be used to characterize how local and regional democracy functions within countries.

Method

- To some extent, these are specific to each state tradition; however, there are also tendencies of change, signifying that models of democracy are being transferred between systems.

Method

We will make a distinction between

five clusters of countries:

- the British Isles (Ireland and the UK),

- the Rhinelandic states (Benelux, Germany, Austria and Switzerland),

- the Nordic states (Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Norway),

- the Southern European states (Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal and Spain)

- the ‘new democracies’ of Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Slovakia).

Method

The main defining criteria for these systems involve:

- the type of state tradition that they reflect.

- State–society relationship,

- Form of political organization,

- Basis of policy style,

- Form of decentralization,

- Dominant approach to the discipline of public administration,

An initial distinction that may be made is between countries in the ‘Anglo’ tradition – the UK, Ireland (as well as the US, Canada, Australia, etc.) – and the countries of continental Europe.

In the Anglo tradition, the ‘state’ as such does not exist in the same way that it exists in the European countries on the continent; that is, as an entity with its own legal personality.

In continental Europe, the state as a "moral actor" (or une personne morale, as the French call it or "osoba prawna" for polish) is capable of entering into contractual relations with other legal entities such as local authorities, universities or, indeed, private enterprises.

In the Anglo tradition, one usually speaks of the ‘government’ or government departments rather than the state.

In continental Europe, the state as a "moral actor" (or une personne morale, as the French call it or "osoba prawna" for polish) is capable of entering into contractual relations with other legal entities such as local authorities, universities or, indeed, private enterprises.

In the Anglo tradition, one usually speaks of the ‘government’ or government departments rather than the state.

Another important difference is that in the Anglo tradition government has traditionally been dominated by society, while in the continental tradition it is instead society that is dominated by the state.

- These differences have influenced other aspects of both approaches to understanding politics, policy and state–society relations.

- For example, in the Anglo tradition, and particularly in the US, politics is dominated by a pluralistic approach emphasizing the role of groups, with government departments being considered simply additional ‘groups’ along with the groups of civil society.

Similarly, public administration is concerned less with constitutional-legal structures than with the power relations that exist behind these structures, as described in the theory of ‘intergovernmental relations’.

The continental European tradition of understanding politics and public administration, on the other hand, has its roots not in the ‘social sciences’ but in public law. This emphasizes the role of the state and parliamentary legislation in defining policy over and above society.

The continental tradition was strongly influenced by both traditions of Roman law and the legacy of the Napoleonic code.

However, there are also interesting differences between the countries of Western continental Europe, which we have summarized under three broad categories:

French, Germanic and Scandinavian.

The contrasts here are most evident between the French and Germanic approaches.

In each case, there is a distinctive understanding of the nature of the state and the nation, as well as the relationship between state and society.

The Germanic tradition has more of a corporatist and organic character, with groups from civil society incorporated into the policy-making functions of the state itself.

The nation is regarded as a corporate body based on a common language and culture that transcended the territorial fragmentation of the German lands during the nineteenth century.

The French tradition is quite different, conceiving of the state as somehow embodying the nation, but viewing the nation as a collection of individual citizens joined together by a ‘general will’.

Sometimes, German nationalism is expressed as ‘ethnos’, while the French understanding is expressed as ‘demos’. One is born into a specific German culture, whereas one may choose to become French.

Of course, the two concepts became intertwined with the arrival of the modern nation-state, since Germanic ethnos also implies demos and French demos has evolved into ethnos, whereby French citizenship also denotes the adoption of French language and culture.

The Scandinavian tradition stands somewhere between the Anglo and the Germanic, but bears some resemblance to the French tradition.

Like the Anglo system, it has a tradition of self-reliant communities, resulting in strong local government; however, as in the German tradition, the Scandinavian countries feature a strong state with some corporatist elements. Like the French tradition, the Scandinavian tradition emphasizes central control and uniformity.

State traditions also express distinct forms of territorial governance. The French tradition tends toward a high degree of centralization and uniformity, whereas the Germanic tradition is marked by organic federalism. The Anglo tradition, given its weak form of the ‘state’, has a pragmatic and ad-hoc form of territorial governance. The Scandinavian tradition, as mentioned above, features a strong central state but also strong local government.

The ‘new democracies’ are more problematic. Although in most cases they have been influenced by the four traditions, they are in fact quite heterogeneous.

While they all share a common history of (so called) communism and authoritarianism and the transition to democracy, their precommunist histories are quite distinct.

Some of them participated in the historical evolution of Western Europe, such as the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Industrial Revolution and the rise of liberal democracy.

Others, in contrast, formed part of the Ottoman or Russian Empires and did not experience these developments to the same extent (e.g. the protest movement of the opposition in the Ukraine is a good illustration of a still problematic relationship with Russia due to its historical legacy.

Although these longer-term historical influences should not be exaggerated, neither should they be ignored; it may be the case that a particular country has historical memories, however deeply repressed, of democratic life, while others simply lack this background.

Models of democracy

In comparative politics, Lijphart has made a fundamental distinction between majoritarian ‘Westminster democracy’ on the one hand and cooperative ‘consensus democracy’ on the other.

He differentiates these along the federal–unitary and the politics–executive dimensions.

Models of democracy

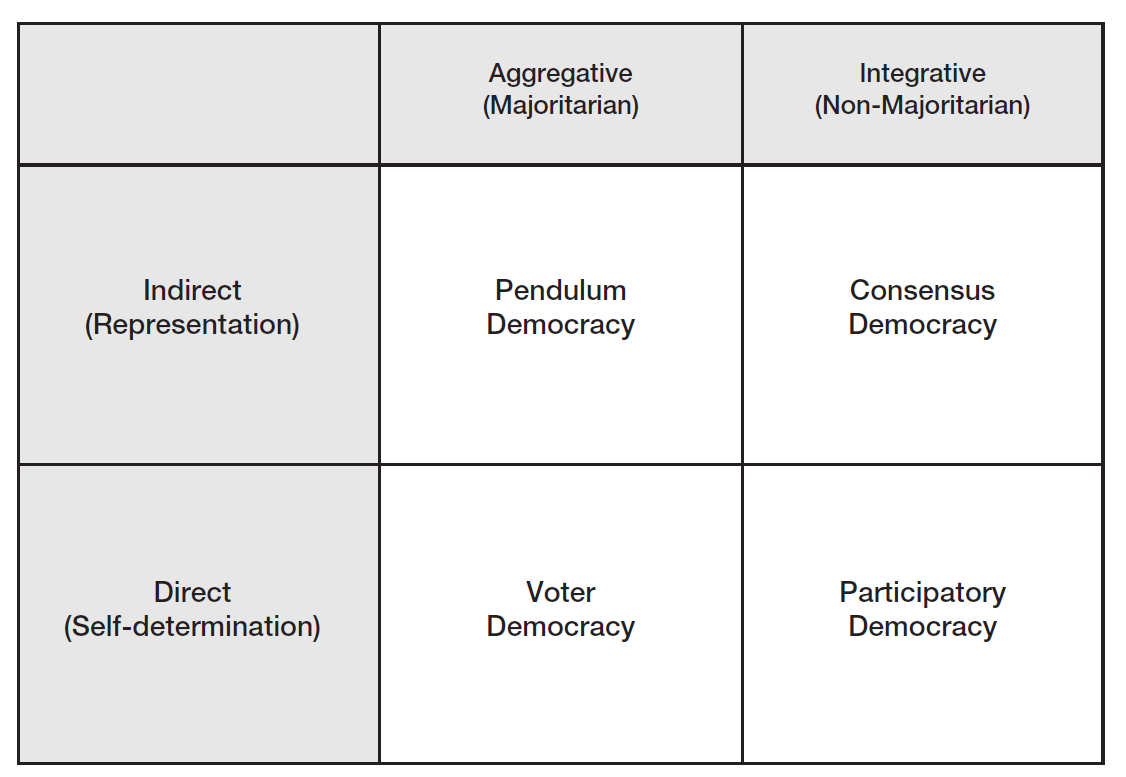

Hendriks (2010) has amended and expanded the Lijphart scheme in order to allow the incorporation of subnational democracy.

He distinguishes between four competing models of democracy by interrelating two basic distinctions.

Models of democracy

The first distinction is between aggregative and integrative democracy, which essentially concerns how democratic decisions are taken.

Are they taken in an aggregative (majoritarian) process, in

which a simple majority eventually wins, even if this majority is opposed by sizeable minorities?

Or are decisions taken in an integrative (non-majoritarian, deliberative) process, in which there is an attempt to reach the widest possible – ideally complete – consensus?

Models of democracy

The second distinction is between direct and indirect democracy. This involves the question of whether citizens take decisions themselves or select representatives who ultimately take the decisions

Models of democracy

Pendulum democracy

- refers to the model of democracy in which political power alternates between two competing political formations and their leaders – like the pendulum of a clock. [polish: zasada wahadła].

- Its best-known manifestation is the so-called ‘Westminster’ model.

- Pendulum democracy is fundamentally indirect and representative in nature.

- Citizens periodically cast their votes and hand over decision-making powers to their elected representatives.

Pendulum democracy

- Decision-making is largely majoritarian and aggregative: the winner takes all in constituencies, because of the ‘first-pastthe-post’ electoral system, and the government is monopolized by the winning party, even if its majority is minimal.

- In pendulum democracy, broad-based citizen participation is limited to the brief period of elections.

- To the extent possible, elected politicians rather than citizens take charge of policy implementation, policy preparation, agenda-setting and political control.

Voter democracy

combines aggregative decision-making with direct popular rule, unmediated by political representation.

Citizens participate in voter democracy by casting their votes in plebiscites, either on a small scale (e.g. assembly meetings) or on a large scale (e.g. referendums).

An example is the New England town meeting, where citizens take decisions on public matters in assemblies.

A more large-scale manifestation of this type is the California-style decision-making proposition (referendum), in which a simple majority decides binary questions (for or against a particular proposition).

Participatory democracy

combines direct self-governance with integrative decision-making.

It is illustrated by classic as well as contemporary cases of ‘communal’ self-rule, involving ‘com - municative’ and ‘deliberative’ citizen governance.

In a participatory democracy, a minority would never be simply overruled by a straightforward numerical majority; the intention is to include minorities, rather than exclude them.

Counting heads only takes place in the final stages of decision-making (if at all) and serves to confirm shared views rather than to take decisions.

Participatory democracy

Decision-making is first and foremost a process of engaging in thorough, preferably trans formative, and usually lengthy deliberations in search of consensus. In a participatory democracy, everyone has the same right to raise and debate an issue, and relationships are largely horizontal, open and ‘power free’.

Consensus democracy

refers to a general model of democracy that can be found in historically divided societies such as the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland and Austria. Consensus democracy is basically indirect and integrative.

Representatives of groups and sections of society are the prime decision-makers. They act in an integrative and consensus-seeking manner, usually in a conference-room or round-table type of setting.

Consensus democracy

Collective decision-making largely takes place through co-producing, co-governing and coalition-oriented methods and aims to establish consensus and broad-based support.

Preferably, the majority will not overrule substantial minorities by simply counting heads; the goal is to build policies on a broad platform of support, both politically and socially.

Models of democracy

Democratic practice is the result of a dynamic process of push and pull between these models of democracy.

Pendulum democracy may be most prominent in some countries, and consensus democracy in others, but these models are never exclusive or uncontested.

Enduring democratic systems, ‘vital democracies’, are usually hybrids of different models.

Subnational change: common themes

- Discussions about the transformation of subnational governance are often highly idiosyncratic, driven by specific institutional or situational challenges in the various countries.

- Nevertheless, there are some general themes that have driven reform agendas in many, if not most, European states.

- We identify and discuss four of these: multilevel governance, interactive governance, the local referendum and the elected mayor.

multilevel governance

This concept refers to the interactions across the different levels of governance – European, national, regional, local – that are increasingly interconnected and interdependent.

The concept was originally developed to describe the evolving relations between the European Union and subnational authorities but it has increasingly been used to analyse interactions between levels of governance both within and between states.

multilevel governance

The European institutions and the EU member states are dependent on each other to function, and there is a need for collaboration with regional and local actors within the various countries.

Multilevel governance is a pragmatic response to these situational and institutional challenges.

However, it does have certain implications for the practice of democracy at both national and subnational levels.

Multilevel governance entails all the disadvantages of intergovernmental networks, due to its strong reliance on professional dealmakers and experts from umbrella organizations.

multilevel governance

At the same time, however, new methods for local and regional governments to exert influence over EU issues have been developed.

The Committee of the Regions, featuring representatives from subnational governments in all member states, was established in the Maastricht Treaty.

multilevel governance

- Although its role is primarily consultative, this institution has highlighted the importance of the local and regional levels vis-à-vis the EU. In addition, subnational governments are represented in Brussels by regional information offices and by their national Local Government Associations.

- This does not mean that subnational governments are equally positioned in Brussels, however: regions with legislative powers seem to have a slightly stronger position due to their unique role as the implementers of EU legislation.

Interactive governance

- This refers to a form of policy-making that has been developed in order to overcome the weaknesses associated with both representative democracy and ‘network governance’ by decision-making experts.

- ‘Participatory’ or ‘deliberative’ democracy, which are variants of interactive governance, are often geared towards ‘bringing the citizen back in’, or at least attempting to make and maintain connections between local and regional policy-makers and citizens. Initiatives include neighbourhood councils, participatory budgeting, participatory regional planning, citizen assemblies and various forms of e-participation.

Interactive governance

- This participatory discourse can be found in all of the country groups that we have identified.

- Although it appears that participatory approaches are more readily accepted in the Rhinelandic group of countries than in the new democracies of Eastern Europe, participatory discourse is somewhat on the rise even in the latter group.

- The British Isles, the Nordic group and the Southern European group lie between these two positions on the continuum, with some countries in the Southern group – Italy, Spain and France – remarkably active in this field.

Interactive governance

- Quite rarely, participatory democracy gains an autonomous position vis-à-vis the established systems of representative democracy. At best, citizens are ‘brought in’ via participatory extensions to the established model of representative democracy.