Elections and electoral systems

The concept of elections

Elections

What is it?

Elections are a common phenomenon and characteristic of the developed world, and at the same time they should be taken as a phenomenon fulfilling various functions and thus occupying different places in particular political systems.

Elections

The very concept of elections means a cyclical process by which a given group appoints representatives to specific positions or to perform specific functions. They may concern various forms of power, appropriate for various social groups - from formalized groups such as associations to the level of the nation (society), where they serve to appoint representatives to perform functions and positions related to the exercise of state power.

Elections

Is that the only known technique used to choose the representatives?

Elections

Is that the only known technique used to choose the representatives?

eg.:

appointment

establishment by succession

Elections

And their use in various systems:

- Democratic

- Non-democratic

Elections

Elections without democratic content can be used in various processes of selection and appointment of representatives in undemocratic (authoritarian or gray-zone) political systems. Given that elections can apply and take place in political systems of a different nature, their meaning would be different, as well as a catalog of functions fulfilled by elections in systems of different nature.

Elections

The understanding of elections in individual political systems determines the freedom of action of political actors and the scope of the widest possible offer, the choice of which is made as well as the widest possible real freedom of choice from among the created offer.

Elections

There is a fundamental difference between a situation when a voter has the (limited) possibility to choose candidates of only one political formation and a situation when the range of possibilities presented to him is wider and contains various candidates of various political groups - both those in power and the opposition so far.

Elections

The distinction between two categories is important here:

- the widest possible offer from which the choice could be made

and

- the actual offer from which this choice is made.

Elections

Refers to the broadest theoretically possible offer that can be created in accordance with existing standards - it is influenced, for example, by allowing a limited set of entities to participate in its construction (eg only political parties when a system does not give freedom of their operation, or only one entity controlled by the authorities).

Elections - the widest possible offer

Defines the offer actually presented to voters during a particular electoral process - its shape depends both on the standards defining the widest possible offer and on other factors, such as the catalog of existing political parties and other entities interested in participating in the electoral process.

Elections - actual offer

The actual offer in most cases will be narrower than the widest possible offer.

Especially in democracies (always)

Elections

The limitation of the widest possible offer is characteristic of undemocratic systems and is followed by the creation of the right preventing entities from participating in building the parts of offer other than controlled (or sanctioned) by the authorities or as a result of administrative decisions resulting in the elimination of the submitted elements.

Limitations of the widest possible offer are also found in democratic systems, however, they are usually of objective and justified nature.

Elections

In contrast to the restriction of the widest possible offer, limiting the offer actually presented to voters does not have to indicate the undemocratic nature of the system in which the given elections are carried out. It may be the result of other factors - for example high level of public support that results in lovering the interest of creation competitive elements of the offer (opposition candidates) or low level of organization of specific groups, preventing them from proposing their own candidates

Elections

There is only one candidate (or only one element of actual offer)?

Elections - what if...

Even the limitation of the actual election offer to one element does not mean that such elections are carried out in the undemocratic system if this limitation does not result from limiting the freedom to create an election offer.

Elections

Competitive elections in contemporary systems relate to the principles that allow to recognize that the process and the end result of a particular election is consistent with the attitudes and will of the electors (electorate). At the same time, these principles capture the normative meaning of liberal democracy:

Elections and democratic system

- Elements of the election offer are subject to equal legal criteria, the fulfillment of which is necessary, but also sufficient for the existence of a given element of the offer.

- There is real competition between candidates (groups of candidates) and competition of political offers (programs).

- Equality of participants in the electoral process is ensured, especially in the area of election campaigning.

Elections and democratic system

- Freedom of choice is ensured by a secret ballot, which is generally understood not as the entitlement (right) , which may be used in an optional way, but as the right and obligation to vote in a manner that ensures secrecy.

[! Why?]

Elections and democratic system

- The existing electoral system is not dishonest or does not negate the democratic result of the election through an unjustified deformation of the will (majority) of voters.

[! But what does it mean?]

Elections and democratic system

- Elections are relatively frequent and cadentional electoral decisions, which means that decisions made during specific elections do not affect the widest possible offer and possible freedom of choice at subsequent elections (or - the possibility and freedom of choice are not limited due to earlier decisions ).

Elections and democratic system

The catalog of functions that can be fulfilled by elections in the democratic system is not clearly defined, and shanges along with the development of modern social relations.

The following may be included:

- legitimization of the political system and faction (party or coalition) in power.

- Transfer of social trust to individuals and parties (factions).

- Recruitment of political elites, including regional or sub-regional elites.

Elections and democratic system (functions)

- Articulation of views and convictions of voters (and broadly - also those entitled to vote knowingly not using the right to vote).

- Social mobilization.

- Awareness of social problems and challenges facing the state in society.

- Control, targeting and mitigation of social conflicts.

- Shaping the community's political will.

- Implementation of the fight for political power and transferring it to the program level.

Elections and democratic system (functions)

- Establishment of the government (as well as other institutions - eg executive bodies of territorial self-government units) or enabling its appointment by forming a collegial body (in the event that none of the groupings has an independent majority, the government arises as a result of cross-party arrangements in which, however, the potential of individual actors depend on the result of the election).

- Forming the parliamentary majority and the opposition (and similar institutions, e.g. at the local government level).

- Allowing the alternation of power.

Elections and democratic system (functions)

Functions of elencions in different political systems

| political system | Democracy | Authoritarianism | Consolidated a. |

|---|---|---|---|

| understanding of the election | competitive | semi-competitive* | non-competitive |

| Freedom of creation of the offer | full (with possible exemptions) | limited* | none |

| Freedom of voter's decision regarding the offer presented | full | partial or none | none |

| The legitimacy of the political system | strong | partial* | none |

Functions of elencions in different political systems

| political system | Democracy | Authoritarianism | Consolidated a. |

|---|---|---|---|

| resolution of the issue of exercising power [Decision who is in power] |

yes | no | no |

| raising citizens' awareness | yes | yes | yes |

| alternation of political elites (possibility) | yes | partial or none | none |

What does it mean to win the election?

Elections and democratic system

- Lorgo (wide) meaning of electoral system

- Stricto (narrow) meaning of electoral system

Electoral system

Broad understanding, dominating most often in countries without long and stable democratic traditions. It contains all the norms, conditions and processes related to the electoral process, including electoral law.

B. Banaszak defines the largo meaning of electoral system as all legal and non-legal principles) specifying how to prepare and conduct the voting and determine the election results.

Largo meaning of electoral system

The most commonly used approach in political science and political science literature.

Patterns of behavior according to which voters express their preferences regarding the party and / or the candidate as well as the method of transforming electoral results into mandatory results. Electoral systems regulate this process by defining: electoral districts, voting methods and methods for determining election results [D. Nohlen].

Stricto meaning of electoral system

"The system of norms, above all the legal ones, governing the process, in which the set of votes cast by voters is transformed into a set of seats symbolizing shares in the exercise of power.

The electoral system is understood as a dynamic system composed of three elements interacting with each other:

1) electoral formula,

2) electoral constituencies structure,

3) electoral rights directly during the election act"

[M. Pierzgalski]

Stricto meaning of electoral system

The narrow perspective of the electoral system, in addition to its dominant position in the literature ofthe subject, seems to be sufficient to study the electoral process and political changes in it.

However, this approach would make it impossible to study all the changes introduced in the election process, affecting the subsequent outcome.

The largo understanding, on the other hand, seems too broad, and it would take too much time to analyze all its aspects.

Meaning of electoral system

The broad approach, in particular, concerns the financing of election campaigns, which are necessarily connected with the whole of norms regulating the financing of political parties or those aspects of criminal law that may affect the electoral process under certain conditions by specifying the electoral rights of the individual, including depriving them of such rights. powers, and finally other regulations indirectly interfering with the electoral system and the party system, which in Poland can include even the norms regulating the functioning of the Register of Political Parties or the constitutional ban on political parties to promote specific content and promote specific political solutions.

Meaning of electoral system

For the purposes of the classes, the broader approach to the stricto meaning of electoral system sensu will apply:

- election formula

- structure of constituencies

- electoral rights directly during the election act

- legal norms shaping the electoral rights of individuals, in particular the right to stand as a candidate, and the manner of submitting candidates to a given body or office.

Meaning of electoral system

The mosaic of electoral systems used in democratic states is extremely diverse.

Not only can't one talk about one "democratic electoral system", but it should be noted that the solutions used are often far from each other, and the implementation of particular election functions occurs with varying intensity.

The basic determinant for the diision of electoral systems is the application of a specific representation principle.

Electoral system - division

Traditionally, the division into

majority

and

proportional

systems is used.

[What are they?]

Electoral system - division

The first is characterized by the fact that a candidate (or party) obtains a majority (absolute or relative) of votes, while the second is characterized by the possibly accurate representation of the party's share in the overall pool of votes for its share in the total pool of available seats.

Electoral system - division

This division seems ok, however - as D. Nohlen or G. Sartori points out - it is asymmetrical. The majority election is determined by the settlement method used, while the proportional elections are determined by the representation method used.

Electoral system - division

Other scholars as the basis for the distinction between majority and proportional elections adopted the size of the constituency: in majority elections, one candidate is elected in each constituency, but if there are more of them - we are automatically dealing with proportional elections.

[Is it right?]

Electoral system - division

The classification of a particular electoral system as a majority or proportional one should result first of all from the effect of the system.

Two categories that allow you to examine and analyze systems:

- resolution rule (settlement method, rule of resolution)

- principle of representation (rule of representation)

Electoral system - division

The rule of settlement refers to the method of determining the distribution of seats in the district (transposing a set of individual electoral attitudes of voters in the district to the collection of seats in the district).

Resolution rule

In majority elections, the mandates are distributed depending on which candidate (or which party, list, etc.) has the most votes (relatively - the most votes and fulfilled additional conditions, for example, the requirement to obtain support not only of the majority voters, but also specific support in the group of all entitled, regardless of their actual participation in the vote).

Resolution rule - majority system

In proportional elections we deal with the possibly accurate representation of the share of votes for a given party (list) in a set of electoral decisions of voters in the district for the collection of mandates possible to be obtained in the district. This requires the determination of a certain amount (required participation in the set of votes) or a ranking list of quotients (depending on the share in the set of votes) for individual lists.

Resolution rule - proportional system

In contrast to the rule of resolution, which is considered at the level of the electoral district, the principle of representation refers to the national level, and in a broader sense - to the level of the whole elected collegiate body or a part of the elected collective body to which the given electoral system applies.

Principle of representation

In Poland, therefore, it refers not only to the Sejm of the Republic of Poland and the Senate of the Republic of Poland, but also to the local self-government bodies - municipal councils (cities), poviat councils and regional assemblies, with the proviso that the representation principle in their case applies both to the general level a specific governing body, as well as a set of bodies constituting territorial self-government units at a given level, and to the election of members of the European Parliament, but only to the extent that their election is subject to the Polish electoral system.

Principle of representation

The principle of representation (which can also be called the purpose of representation) is different for both types of electoral systems.

The majority system aims to provide one party (one faction) the majority of places in a body that allows it to create government (and similar bodies), whilst it is not important whether a given party (faction) has gained the support of the majority of voters.

The main function of the election is in this case to provide the majority capable of forming a cabinet.

Principle of representation

In the proportional system, the principle (goal) of representation is to ensure the best possible reflection of the social (electoral) support of particular groups in a collegial electoral body.

Principle of representation

In other words:

The majority rule of representation presupposes such a mapping of a set of electoral decisions for a set of seats so the share of one of the factions is significant enough to enable governance (which usually means more than half of the seats), while the proportional representation principle assumes the best representation of each fraction's share in the electoral decisions for participation in a set of seats.

Principle of representation

The principle of representation and the rule of settlement

| Type of electoral system | Rule of resolution (settlement) | Principle (purpose) of representation |

|---|---|---|

| The majority system | The majority share wins | Creating the majority |

| The proportional system | Participation in votes gives participation in mandates | Possibly the ideal representation of voters' preferences |

From the set of possible electoral systems, two subsets can be distinguished:

the first - classic electoral systems, in which the rules for the determination of specific electoral systems are appropriate for the adopted rules of representation (specific, "model" examples will be both elections according to the formula of a relative majority in single-member constituencies as well as elections carried out according to a proportional formula in one, multi-mandate electoral district in which the allocation of all available seats takes place);

the second subset will be combined systems in which the applied resolution rule does not coincide with the adopted representation principle.

The principle of representation and the rule of settlement

The classification of a particular electoral system to one of the two basic types will be determined by the adopted principle of representation as superior to the technical aspects of the system, including the rules of resolving.

The principle of representation and the rule of settlement

An example of a combined system is a single transfer vote system (STV), which - despite the rule based on achieving the amount (appropriate for proportional systems) - in certain conditions implements the principle of representation appropriate for majority systems, especially when it occurs in a relationship with small (especially 2-, 3-mandate) electoral districts. Another example is the application of the principle of resolving proportional elections in the aforementioned small constituencies - such a combination of technical elements of the system, including in particular high natural thresholds, lead to the implementation of the principle of representation proper again for majority systems

The principle of representation and the rule of settlement

An example of a combined system is a single transfer vote system (STV), which - despite the rule based on achieving the amount (appropriate for proportional systems) - in certain conditions implements the principle of representation appropriate for majority systems, especially when it occurs in a relationship with small (especially 2-, 3-mandate) electoral districts. Another example is the application of the principle of resolving proportional elections in the aforementioned small constituencies - such a combination of technical elements of the system, including in particular high natural thresholds, lead to the implementation of the principle of representation proper again for majority systems

The principle of representation and the rule of settlement

[Also, You can meet third group - mixed electoral systems, so what about them?]

The principle of representation and the rule of settlement

The principle of representation and the rule of settlement

| Dimension | Majority s. | Proportional s. |

|---|---|---|

| Preservation of the material equality of voices within the constituency | ||

| Perception of linking the voter's voice with the election results in the district | ||

| Preservation of the material equality of voices at the level of the entire elected body |

The principle of representation and the rule of settlement

| Dimension | Majority s. | Proportional s. |

|---|---|---|

| Preservation of the material equality of voices within the constituency | defective | Possibly full |

| Perception of linking the voter's voice with the election results in the district | Simple | Complicated |

| Preservation of the material equality of voices at the level of the entire elected body | Possible under certain conditions, more often defective | Possible full, under certain conditions, are disorders |

The principle of representation and the rule of settlement

| Dimension | Majority s. | Proportional s. |

|---|---|---|

| Perception of linking the voice of voter groups with the outcome of elections at the general level | ||

| The importance of dominated electoral districts | ||

| Share of wasted votes |

The principle of representation and the rule of settlement

| Dimension | Majority s. | Proportional s. |

|---|---|---|

| Perception of linking the voice of voter groups with the outcome of elections at the general level | Complicated | Straight |

| The importance of dominated electoral districts | Significant | Limited |

| Share of wasted votes | Relatively high | Limited |

The principle of representation and the rule of settlement

| Dimension | Majority s. | Proportional s. |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy of the mandate towards the election group | ||

| Responsibilities of the mandate to the voters | ||

| Perception of linking a potentially implemented electoral program with the voter's voice |

The principle of representation and the rule of settlement

| Dimension | Majority s. | Proportional s. |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy of the mandate towards the election group | Depending on other factors - from limited to significant |

Limited (with exceptions) |

| Responsibilities of the mandate to the voters |

direct |

Limited |

| Perception of linking a potentially implemented electoral program with the voter's voice |

Limited | Straight |

Typology of electoral systems

| Majority s. | Proportional s. |

|---|---|

| FPTP (First Past the Post) | Largest remainder method |

| PBV (Party Block Vote) | Highest averages method |

| BV (Block Vote) | STV (Single Transferable Vote) |

| AV (Alternate Vote) | Segment Systems* |

| SNTV (Single Nontransferable Vote) | Compensation Systems* |

| LV (Limited Vote) | |

Elements of the electoral system

-

electoral formula

- structure of constituencies

- electoral rights directly during the election act

- legal norms shaping the electoral rights of individuals, in particular the right to stand as a candidate, and the manner of submitting candidates to a given body or office.

Structure of constituencies

We may say (risk the statement) that while the reformulation of the results of voting in the one district on the results of the election is directly dependent on the electoral formula used, the reformulation of the result of voting on the level of the entire elected body on the overall election result is primarily dependent on the structure of electoral districts.

Structure of constituencies

Constituency:

1. a separate part of the area on which elections to the collegial body are carried out, on which the aggregation of votes and the allocation of seats take place.

2. a separate part of the area on which elections to the collegiate body are carried out, where the aggregation of votes takes place, however, it is not related to the distribution of seats.

Structure of constituencies

Function of division into electoral constituences:

1. allowing proportional (equal, fair etc.) representation of different regions (areas) in the composition of the chosen body, which is of particular importance in the event of a conflict between the center and the periphery,

2. reduction of the maximum election offer (offers of candidates) presented directly to a single voter, thanks to which he has a greater opportunity to learn about the offer presented to him and make a choice consistent with his interests and views,

Structure of constituencies

Function of division into electoral constituences:

3. determining the actual level of proportionality of the electoral system and influencing the final effect of the election formula.

It can be stated that while the reformulation of voting results in the district on the election results depends directly on the voting formula used, the reformulation of the voting result at the level of the entire elected body on the overall election result is primarily dependent on the structure of electoral districts.

Structure of constituencies

The importance of division into electoral districts:

- the division into electoral districts directly refers to the issue of maintaining the principle of equality of elections,

- ensuring equal opportunities for all participants in the electoral process and ensuring an equal impact of their (equivalent) actions and acts on the electoral process and its outcome,

- Electoral equality should be treated as one of the elements of political equality, indicated as one of the basic constitutional values of democratic states in their highest-level normative acts (eg in the Constitution of the Republic of Poland, including the preamble and article 11).

Structure of constituencies

Function of division into electoral constituences:

-

The notion of political equality reflects the classical definition of R. A. Dahl and C. Lindblom defining political equality as "control over decisions of the authorities in such a way that the preference of one citizen does not matter more than the preference of every other citizen",

Structure of constituencies

Function of division into electoral constituences:

- CS Quińiones: equality in the electoral law is when there are no natural or accidental disadvantages that lead to its distortion. The consequence of adopting such a position is to ensure equality as a form of fair elections by removing these election mechanisms and the law regulating them, which lead to the disturbance of real equality in the electoral process. equality is simply understood as ensuring coherent and identical conditions of rivalry for the actors of the political scene in the election.

Structure of constituencies

Aspects of electoral equality

- Formal

- Material

- Fair-Play

First two of them are comonly recognised, whilst "fair play" is rather new, currently geting into use.

Structure of constituencies

Function of division into electoral constituences:

- Ensuring the perfect material equality of the elections, also at the stage of the division of the area on which the elections are conducted, is practically impossible.

- It results directly from the discreet character of the number of seats (it is not possible to assign part of the mandate to the district, as well as to the party or the candidate).

- Therefore, the phenomenon of inequality is objective.

Structure of constituencies

Function of division into electoral constituences:

- The division into electoral districts can implement the principle of equality in different ways. It can also benefit particular parts of the area where the elections are being held or specific political parties (candidates).

The phenomenon of uneven representation is determined by the term malapportionment.

Structure of constituencies

Function of division into electoral constituences:

- Historically, the phenomenon of improper division was most often associated with the lack of updating the boundaries (or sizes) of constituencies despite migration processes.

The so-called. "broken districts" in Great Britain.

Structure of constituencies

Features of the constituency:

1. The size of the constituency - the number of seats assigned to the district, which are to be distributed in it,

2. number of inhabitants (or people entitled to vote) residing in the area of the district,

3. (District shape) - district boundaries including the distance between the border points,

Structure of constituencies

The size (number of seats S) of districts is a key parameter of the electoral system affecting the preservation of the material equality during the elections and the proportional effect of the share of a given political group in in the entire elected body.

The basic distinction is the division into:

- single-mandate constituences, by their very nature, enforcing the use of the majority formula

and

- multi-mandate constituences leaving freedom of choice of the electoral formula.

Structure of constituencies

Among the functioning multi-mandate constituencies there are both two- and three-seats districts as well as districts in which all seats are allocated for distribution (eg in the elections to the Lower House of the Dutch parliament, the 150-seat district and 120-seat district in Israel).

Due to the number of seats, the constituances can be very different and their use give different effects.

Structure of constituencies

| Author | small constituences | medium constituences | big constituences |

|---|---|---|---|

| D. Nohlen | 2-5 | 6-9 | 10+ |

| M. Gallagher | 2-9 | - | 10+ |

| F. Tuesta Soldevilla | 2-5 | 6-10 | 11+ |

| G. Sartori | 2-7 | - | - |

Structure of constituencies

You can encounter divisions radically different from those indicated above.

For example, P. Uziębło indicates that "districts, which include fewer than a dozen or more (11+) seats, cause significant deformations, which grow with decreasing number the seats".

Structure of constituencies

The defined structure of electoral districts largely determines the effects of the electoral system.

It may, however, have various consequences depending on the structure of the party system, support structure.

E.g.: districts with fewer seats will deform the results of voting more in the case of a fragmented political scene with several parties with 10% support and one dominant party, e.g. with around 35% support rather than in a system with a fragmented structure in which the dominant party does not exist).

Structure of constituencies

| SMC | MMC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMC | small constit. | medium constit. | big constit. | very big const. | one constit. | |

| Numberof seats (S) | 1 seat | 2-5 | 6-9 | 10-18 | 19+ | all seats |

| Exclusion treshold | 50% | 16,67%-33,33% | 10%-14,29% | 5,26%-9,09% | max. 5% | <5%, going to 0 |

Structure of constituencies

Problems related to the structure of constituencies

- The way of calculating the number of seats in the district (especially limping in Poland),

- The entity entitled to apply for changes and to adopt them (who changes the structure or who starts the process of changing the structure),

- Depoliticization of the process of determining the structure of constituencies.

Structure of constituencies

The basic questions are:

How do you win the elections even though you do not have the majority support?

How to win the election despite having minority support?

Structure of constituencies

A thing to remember:

Winning the voting does not necessarily mean winning the election.

Structure of constituencies

A thing to remember:

Winning a vote does not necessarily mean winning the election

(What is more) In practice, electoral victory does not always mean political victory, and electoral defeat does not necessarily mean political failure.

Electoral formula

While the structure of electoral districts has the hightest influence on the overall election result, the distribution of seats within the electoral district mainly depends to the electoral formula used.

By electoral formula we understand the function transforming the set of individual electoral decisions of voters in the electoral district into a set of seats allocated within this district.

Electoral formula

Types of electoral forulas:

- of majority representation,

- of proportional representation

Electoral formula

Electoral formulas, due to their importance for the effect of the electoral system, as well as the fact that they focus the interest of decision-makers and the public opinion (especially in the case of changing formulas), usually determine the names of entire systems - we can find, for example, the term d'Hondt system (Jefferson-d'Hondt system).

Electoral formula

- Historically, the first formulas used were the majority formulas.

- Characterized by the relative simplicity of functioning.

- A "pure" or "model" example of the functioning of this formula is the FPTP formula that requires application in single-member constituencies.

Electoral formula

- In this case, the mandate is assigned to the candidate who obtained the largest number of votes in the district (relative majority).

- In addition to the condition of obtaining the highest support, part of the majority formulas puts additional - the requirement of obtaining a certain support (absolute majority or expressed as a percentage of votes) or the turnout requirement (most often 50%).

Electoral formula

- If additional conditions are not met, a second voting takes place (the so-called II round), in which the set of candidates is limited according to the adopted criteria.

- In a repeated vote, it is usually sufficient to obtain a relative majority, although there are also cases of additional requirements.

- The majority formulas are also applicable in multi-mandate electoral districts - in this case we need to find a subset of S candidates with the highest scores, where S is the number of seats to be filled in the district.

- Again, additional requirements may be set in this case.

Electoral formula

- Proportional electoral formulas were formed historically later than majority ones.

- In addition, they initially served not to allocate the mandates to the parties, but to allocate seats to constituencies.

- Their principle is to provide the exact representation for the party acording to the electoral support on constituency level.

Electoral formula

- This assumption can be supplemented as follows:

Ensuring the most (possible) accurate representation of support for a given party in a set of seats in a constituency.

Electoral formula

- Proportional electoral formulas use different methods of division of seats, which they also owe their names to.

-

The methods of division of seats can be divided into two types:

- methods of the largest remainder (in other words: quota methods, methods based on a priori quota, methods based on a fixed quota)

- methods of the highest averages (in other words: the methods of the highest numbers, methods based on a posteriori quota, divisor method).

Electoral formula

- A common feature of the largest reminder methods is basing them on the so-called Election quotas.

- Electoral quotas assume different, though similar, forms, while the simplest is V / S (simple Hare quotient or simple norm of representation), obtained by dividing the number of validly cast votes (V) by mandates to be distributed in the district (S) .

Electoral formula

- By modifying a simple norm of representation, one may get further methods of division of seats, and thus - subsequent election formulas.

- Modifications of the quota by increasing its denominator (adding fictitious seats to it) may be beneficial for the party with the highest support, as it makes winning at least half (or, by analogy, the majority) of seats in the district easier.

Electoral formula

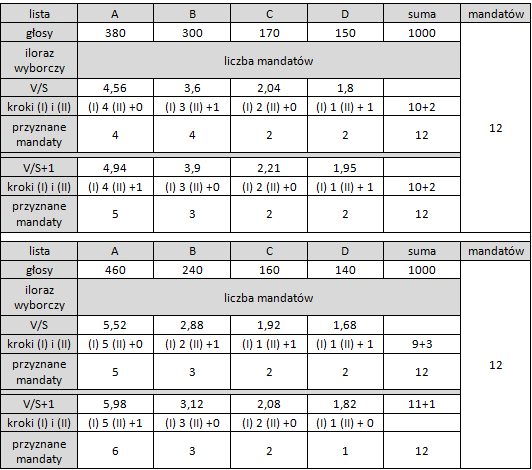

An example of the impact of modifying simple norm of representation on the possibility of obtaining at least half of the seats in a constituency by one party

Electoral formula

-

The artificial increase of the denominator in V / S is beneficial to the strongest parties.

-

In both cases, the increase in the denominator resulted in an increase in the share of the strongest party in the set of mandates to be distributed in the district,

-

in the first case at the expense of the second strongest grouping, while in the second - at the expense of the weakest.

-

What's more, in the second of the presented examples, increasing the denominator's value enabled the strongest party to obtain half of the seats despite obtaining only 46% of votes in the district.

Electoral formula

-

The procedures used to allocate seats using the largest reminder method are relatively simple.

At the first stage, the number of votes obtained in a given group by particular groups (vi) is divided by the adopted electoral quotient. The results obtained in this way take the form Xi, Yi, where Xi is the integral part of the result, while Yi is its fractional part.

In the first step, individual groupings are assigned seats in the number equal to Xi. Apart from extreme cases, after such a division, there are still remained mandates not assigned to any party.

Electoral formula

-

In the second step, the seats that have not been separated so far are assigned to the parties whose part Yi of the result of division are the highest (parties whose the reminder [rest] resulting from the division performed are the highest - that gives the name of formula).

Electoral formula

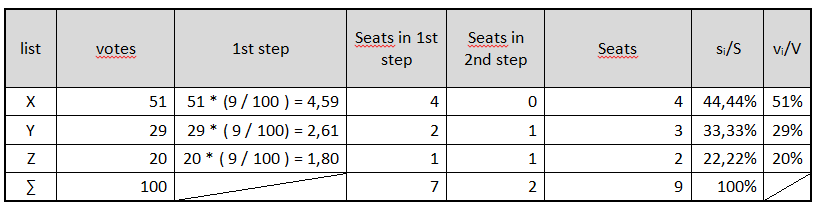

Hare-Niemeyer method, Hamilton method

- 1. Determine the number of mandates to be allocated in district S and the number of validly cast votes V,

- 2. Set the value of the quotient for the method used (in this case V / S),

- 3. Determine the number of seats to be received by each of the lists - multiples quotient included in the number of votes obtained by the list of a given party: si = vi * S / V = Xi, Yi,

- 4. Give each party (list) mandates equal to Xi,

- (5). If all mandates have been allocated - the end of the procedure.

Electoral formula

Hare-Niemeyer method, Hamilton method

- 5. Determine the value of Y = S-X where X is the sum of all Xi (and Y is the sum of all Yi),

6. Assign an additional mandate to the Y lists for which the reminder (Yi) is the highest.

Electoral formula

The Hare-Niemeyer method may result in the distribution of seats favorable to small parties.

Quota methods are considered to enable a fairly accurate representation of the proportion of votes in the ratio of seats, but they are exposed to a number of anomalies.

In addition, in extreme cases, an absolute majority of votes may give less than the absolute majority of seats in the district.

Electoral formula

Electoral formula

Anomalies that may occur when using the largest residue method are referred to as paradoxes. Three of them are most often referred to:

1. The Alabama Paradox,

2. Population paradox,

3. New state paradox.

Electoral formula

The Alabama paradox occurs when, with an unchanged set of individual electoral decisions, and thus - the shares of particular parties in this set - and with the increase of the number of seats to be disposed of in the district, the given party is granted fewer seats than previously.

Electoral formula

The Alabama paradox occurs when, with an unchanged set of individual electoral decisions, and thus - the shares of particular parties in this set - and with the increase of the number of seats to be disposed of in the district, the given party is granted fewer seats than previously.

Electoral formula

The Alabama paradox

Electoral formula

The population paradox takes place when the increase in the initial number of voters leads to assigning a given party (with a cpnstant number of votes) a smaller number of seats than if the number of voters did not increase, while in parallel another group for which the number of votes was decreased, gets more seats than before the change

Electoral formula

The new state paradox takes place when, with the unchanged number of votes cast for given parties and the constant number of seats, after the participation of the additional grouping in the split, the participation of any party already allowed to participate in the distribution of seats in the set of mandates to be distributed in the constituency will increase.

Electoral formula

The new state paradox takes place when, with the unchanged number of votes cast for given parties and the constant number of seats, after the participation of the additional grouping in the split, the participation of any party already allowed to participate in the distribution of seats in the set of mandates to be distributed in the constituency will increase.

Largest divisors methods

The methods of the largest averages, also called the methods of the largest divisors, use methods based on the ordering of the following quotients created by dividing the number of votes obtained by particular parties in the constituency by successive divisors appropriate for the given method.

Largest divisors methods

The simplest of them, and at the same time one of the most commonly used in the democratic world, is d'Hondt method. This method uses the procedure according to which successive divisors used to calculate the quotients are consecutive natural numbers with omitting zero (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ...). The number of successive divisors can not be determined without knowledge of the size of shares of particular groups in the set of valid votes, but it is never greater than the number of mandates to be distributed in the constituency.

Largest divisors methods

After the calculations we get a series of quotients.

Among them, the highest values are selected in an amount equal to the number of seats to be assigned.

The share of quotients of a given party in the [resulting] set means the number of seats obtained by the party.

Largest divisors methods

Among the methods of the largest divisors, also other electoral methods are used. The most popular methods, apart from the d'Hondt method, are the Sainte-Laguë method and various modifications (forming a subset of modified Sainte-Laguë methods).

They are also the only methods of the largest divisors used, apart from the d'Hondt method, in electoral systems in Poland. In its classic form, the Sainte-Laguë method uses a set of divisors, which are successive odd natural numbers (1, 3, 5, 7, 9 ...). Its modifications rely on changing the first divisor (1) by assigning a different value to it.

Largest divisors methods

In practice, the modified Sainte-Laguë method is comonly used with the first divisor 1.4.

This means that the sequence of dividers takes the form: (1,4; 3, 5, 7, 9 ...). It can also be described in a different way: DivZ = (10z-5) / 7 (Z> 1) -> (1, 2.14, 3.57, 5, 6.43 ...). Proportions of the values of subsequent successive divisors and individual successive ones to the first divisor are very close to those resulting from the above-mentioned series.

Largest divisors methods

In practice, the modified Sainte-Laguë method is comonly used with the first divisor of 1.4.

This means that the sequence of dividers takes the form: (1,4; 3, 5, 7, 9 ...). It can also be described in a different way: DivZ = (10z-5) / 7 (Z> 1) -> (1, 2.14, 3.57, 5, 6, 43 ...). Proportions of the values of subsequent successive divisors and individual successive ones to the first divisor are very close to those resulting from the above-mentioned notation.

But.............

Until now, I have presented you with a certain way of understanding the d'Hondt and Sainte-Laguë methods.

But we have a problem.

What I told you was not the d'Hondt and Sainte-Laguë methods.

Suprised?

But.............

After all, in every encyclopedia, even in Wikipedia, it presents such definitions.

Even all handbooks use them.

Even legal documents like electoral law or the electoral code use this form.

So: did your teacher go crazy, did he get it wrong or did the current conditions of the electoral process confuse everything?

But.............

In fact, this understanding of d'Hondt and Sainte-Laguë meotd is simply more convenient and easier to understand.

But he doesn't show us their logic.

What's more, this understanding of methods means that the distinction between methods based on a priori quota and based on a posteriori quota is neither simple nor intuitive.

But.............

Let's check.

Where do we have quota in methods based on a priori quota? (also called methods of the largest remainder, quota methods, methods based on a fixed quota)

But.............

Of course, we know the quota, because it's given before we start calculating.

[for example: simple quota V/S, Droop quota V/(S+1)]

We used them during calculations. We divided the number of votes given to the party (vi) by them and the result meant the number of seats given to the party (si). Of course, we had to deal with fractions.

But.............

So now:

Where do we have quota in methods based on a posteriori quota? (also called methods of the highest averages, the methods of the highest numbers, divisor methods).

But.............

In fact, we don't see the quota. What is more, we don't need the quota to calculate number of seats given to each party.

We don't need it because we divide the number of votes by 1, 2, 3, ... (or 1, 3, 5 ...)

But.............

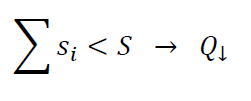

However, the original d'Hondt method (and others after it) looked a bit different.

D'Hondt method

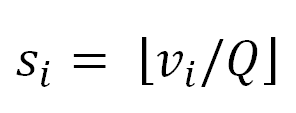

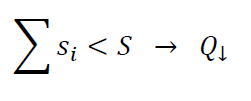

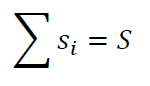

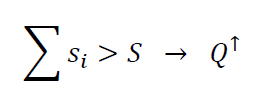

The oryginal d'Hondt method

Set a quota. Give each party as many seats as the rounded down quotient of their number of votes and quota is.

If the sum of the seats is too high, repeat the process increasing the quota.

If the sum of the seats is too small, repeat the process reducing the quota.

The distribution is correct if the number of seats awarded is correct.

D'Hondt method

Set a quota. Give each party as many seats as the rounded down quotient of their number of votes and quota is.

If the sum of the seats is too high, repeat the process increasing the quota.

for example

rounding down of 4.25

= 4

D'Hondt method

If the sum of the seats is too small, repeat the process reducing the quota.

The distribution is correct if the number of seats awarded is correct.

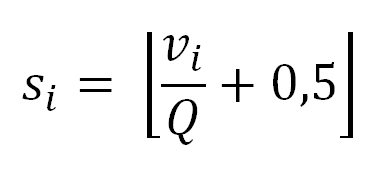

Sainte-Laguë

The original Sainte-Laguë method (and others after it) looked a bit different.

Set a quota. Give each party as many seats as rounded to the nearest whole number by the quotient of its number of votes and quota.

If the sum of the seats is too high, repeat the process increasing the quota.

If the sum of the seats is too small, repeat the process reducing the quota.

The distribution is correct if the number of seats awarded is correct.

Sainte-Laguë method

Set a quota. Give each party as many seats as the rounded quotient of their number of votes and quota is.

If the sum of the seats is too high, repeat the process increasing the quota.

rounding of 4.25 = 4

rounding of 4.55 = 5

Text

from 0 to 0,7 --> round down

0,7 --> round up --> = 1

Sainte-Laguë method

If the sum of the seats is too small, repeat the process reducing the quota.

The distribution is correct if the number of seats awarded is correct.

Consequences of using particular methods

The use of various methods, and thus the formulas, is, as already mentioned, a decisive factor in the proportionality of the distribution of seats in the constituency, and indirectly - the proportionality of the distribution of seats in the entire body from the given elections.

Consequences of using particular methods

The basic difference between the application of the quota and divisional methods is their dependence on particular parameters of the voting result.

In the most general terms - the result of applying both groups of methods in a given electoral district, in which a certain number of seats is filled, depends on other elements of the voting result in a given district.

Consequences of using particular methods

For the quota methods, the most important is the share of votes cast on a given electoral list in a set of votes cast in the district. In this case, the proportions of the number of votes relative to other lists are much less important.

Consequences of using particular methods

For the quota methods, the most important is the share of votes cast on a given electoral list in a set of votes cast in the district. In this case, the proportions of the number of votes relative to other lists are much less important.

Consequences of using particular methods

Irrespective of the electoral quotient used, for each list in the constituency the quotient taking the form Xi,Yi is determined (where Xi is the integral part and Yi the remainder of the division carried out for the result of the list i).

According to the logic of the functioning of the quota methods, the share in the set of mandates to be distributed in a given district may be equal to Xi or Xi + 1, depending on whether the rest of Yi will be in the set of the next largest residues with the number of items remaining to be filled after the division made on the basis of a part of the total quotients Xi.

Consequences of using particular methods

In this case, the proportion of votes cast on the list to the share of votes cast on other parties is of secondary importance - only the ratio of the rests is considered and only when the seats in the second step are divided.

The logic of the system looks different from the point of view of the parties whose lists do not obtain seats at the stage of their distribution due to the amount of the integral parties of Xi,Yi, (groups that can only count on obtaining a mandate at the stage of the allocation of seats by the rests of Yi).

Consequences of using particular methods

In this case, the proportion of votes cast on the list to the share of votes cast on other parties is of secondary importance - only the ratio of the rests is considered and only when the seats in the second step are divided.

Consequences of using particular methods

The logic of the system looks different from the point of view of the parties whose lists do not obtain seats at the stage of their distribution due to the amount of the integral parties of Xi,Yi, (groups that can only count on obtaining a mandate at the stage of the allocation of seats by the rests of Yi).

The possibility of obtaining a mandate by such formations is influenced by a number of factors: the size of the constituency ("the higher the better"), and the number of groups taking part in elections and obtaining at least minimal support and the resulting fragmentation of votes.

Consequences of using particular methods

The basic difference between divisional and quota methods is their sensitivity to different parameters of the election result (distribution of votes). While the logic of the quota methods meant that the share in the set of mandates disposed in the constituency is dependent on the vi / V ratio, the direct dependence of this type does not appear in divisional methods. The number of seats that a given list can get is not a mutually limited set, depending on the share in the total number of votes.

Consequences of using particular methods

Participation in the set of seats is dependent on the proportion between the number of votes obtained by a given list and those obtained by individual other lists (vi / vj, vi / vk, vi / vl ...). This means that it is possible to overrepresent individual lists in shares in the set of seats distributed in the district.

Consequences of using particular methods

| list | A | B | C | D | E | F | sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| votes (vi) | 55 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 100 |

| Div1i=vi/1 | 55 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| Div2=vi/2 | 27,5 | 4,5 | 4,5 | 4,5 | 4,5 | 4,5 | |

| Div3=vi/3 | 18,33 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Div4=vi/4 | 13,75 | 2,25 | 2,25 | 2,25 | 2,25 | 2,25 | |

| Div5=vi/5 | 11 | 1,8 | 1,8 | 1,8 | 1,8 | 1,8 | |

| Div6=vi/6 | 9,17 | 1,5 | 1,5 | 1,5 | 1,5 | 1,5 | |

| si= | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Consequences of using particular methods

In the presented example, list A obtained all 6 seats allocated for distribution in a given district, despite winning slightly above half of the votes. The 50% limit is irrelevant in this case, as an example can be cited, in which a list with significantly lower support gets all the seats - the only condition that must be met is DivSi> {Div1j, Div1k, Div1l, ...}, where Div1i, Div2i , Div3i ... DivSi mean the subsequent quotients created by dividing the number of votes cast into a given i-th list by successive divisors appropriate for the given method (in the presented example - using the d'Hondt method, they are successive natural numbers, omitting zero: 1, 2, 3, 4, ...) and S is the number of seats to be distributed in a district.

Consequences of using particular methods

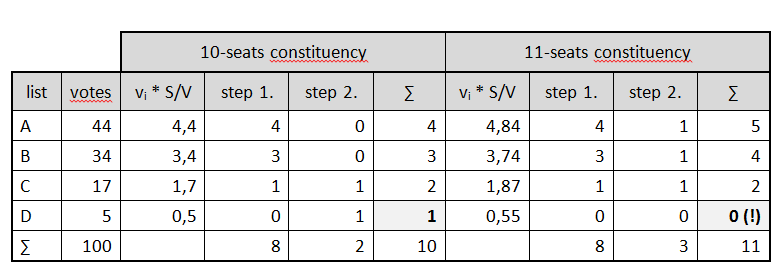

In comparison with the quota methods, it is clear that in the case of divisional methods, it is not possible to indicate the upper limit of the number of mandates possible to obtain in a given district in relation to the votes obtained. At the same time, it is not possible (*) for a committee to obtain a smaller number of seats than the integral part Xi of the expression Xi, Yi resulting from the action vi * S / V, so it is possible to determine the set of values that a given list can take part in the set of seats to be separation in a circle. This set takes the form {Xi, Xi + 1, Xi + 2 ..., S}.

Consequences of using particular methods

In fact, we can determine individual values even more precisely.

It is characteristic of the d'Hondt method that the cost of each subsequent mandate is identical (as opposed to, for example, S-L). We can therefore conclude that in each case si> = Xi where Xi is integral of vi * S / V, but we can even use here: vi * (S + 1) / V. The result of the new equation will of course not be smaller than the previous one. However, you must make a reservation: this rule will not work if all lists get the number of votes being a multiple of V / (S + 1).

Consequences of using particular methods

In the case of S-L and other methods in which the cost of each subsequent mandate is higher, more problems arise.

These are the so-called not sticking to the quota, which means that the number of seats obtained may be lower than Xi. For this method, the minimum number of seats is equal to:

si(min) = ([vi*S/V] + 1) / (2 - [vi/V]).

Consequences of using particular methods

Fortunately, the smarter than me, calculated the risk that the S-L method would not keep the uota. And for example, in the elections in the United States with the distribution of seats in the House of Representatives between states, the risk is 1: 1600.

Therefore, it can be assumed that the number of seats with the S-L method is likely to be included in the set {Xi, ..., S}.

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

The use of various methods, and thus the formulas, is, as already mentioned, a decisive factor in the proportionality of the distribution of seats in the constituency, and indirectly - the proportionality of the distribution of seats in the entire body from the given elections.

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

Electoral equality (mateiral aspect).

The material aspect of the equality principle is connected with striving to guarantee the same “voting power” to the election participants. Most briefly, it means that a given number of people elect as many representatives as another group with the same numerical strength.

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

Electoral equality (mateiral aspect).

How to calculate voting power of voters (in a constituency)?

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

Electoral equality (mateiral aspect).

How to calculate voting power of voters?

We may use cost of a seat Cs = si/vi.

1. Voting power of votes cast in favour of a party that gains NO seats in a constituency is equal 0.

2. VP of other votes may be calculated:

vi/si

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

Electoral equality (mateiral aspect).

For example:

Party A: 3.000 votes, 2 seats

vi/si = 3.000/2 = 1500

si/vi = 0,000667

Party B: 2.000 votes, 1 seat

vi/si = 2.000/1 = 2.000

si/vi = 1/2000 = 0,0005

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

Electoral equality (mateiral aspect).

The higher cost of a seat is - the lower is voting power

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

Electoral equality (mateiral aspect).

Main issue:

How electoral method affects voting power?

Which electoral methods can cause greater differences in voting power?

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

Electoral equality (mateiral aspect).

The biggest differences in the volume can be caused by quota methods.

Remember:

TI = 1/S*L

TN (or TE) = 1/S

The maximum possible difference of voting power is practically unlimited.

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

Difference in voting power between the strongest and weaker votes in the 1991 Sejm elections using the Hare-Niemeyer method

| okr. | list | vi | Xi | Yi | si | vi/si | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | 17036 | 0 | 0,5646 | 1 | 17036 | 181,54% |

| - | 30927 | 1 | 0,0249 | 1 | 30927 |

| 34 | + | 11525 | 0 | 0,3481 | 1 | 11525 | 378,32% |

| - | 43601 | 1 | 0,3170 | 1 | 43601 |

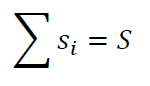

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

Difference in voting power between the strongest and weaker votes in the 1991-2015 Sejm elections if the Hare-Niemeyer method was used.

| Year of ellections | medium proportion | the lowest proportion | the highest proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 280,45% | 181,54% | 378,32% |

| 1993 | 325,60% | 196,80% | 528,15% |

| 1997 | 254,86% | 112,97% | 451,97% |

| 2001 | 208,35% | 127,74% | 295,80% |

| 2005 | 218,13% | 136,58% | 328,52% |

| 2007 | 175,28% | 104,46% | 401,82% |

| 2011 | 176,85% | 110,08% | 337,95% |

| 2015 | 231,02% | 148,78% | 350,94% |

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

Electoral equality (mateiral aspect).

In practice, if we use quota methods, the difference in voting power will occur mainly in fawour of smaller (weaker) parties.

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

The difference in voting power will be lower if divisor methods are used.

However, the direction of inequality may change - especially in the case of the d'H method, we should expect benefits for the stronger party.

In addition, in the case of divisor methods, we are able to indicate the maximum possible levels of inequality.

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

Apart from the rules for settling ties (tie-breaks), they are:

- for d'H 200%,

- for S-L 300%,

- for S-L with the first divider 1.4 slightly above 214%.

Consequences of using particular methods (part II)

In practice:

In how many constituences would we see inequality in favor of a stronger party?

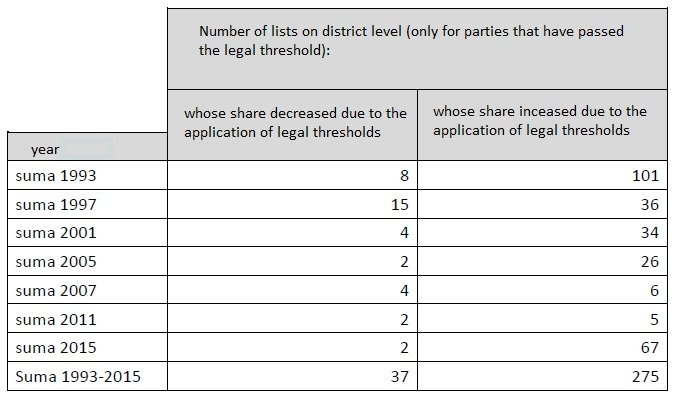

Consequences of using particular methods (part III)

Problem of paradoxes - new state paradox in practice.

What would happen if we use quota method (ie. H-N) and legal threshold (let's say 5% on national level)?

How often the new state paradox would happen?

That is, how often would the introduction of a legal threshold cause a loss for a party whose support is higher than the threshold value?

Consequences of using particular methods (part III)

Problem of paradoxes - new state paradox in practice.

What would happen if we use quota method (ie. H-N) and legal threshold (let's say 5% on national level)?

How often the new state paradox would happen?

That is, how often would the introduction of a legal threshold cause a loss for a party whose support is higher than the threshold value?

Consequences of using particular methods (part III)

Problem of paradoxes - new state paradox in practice.

Electoral thresholds

Electoral thresholds

1. Natural thresholds

- nominal natural threshold

- threshold of exclusion

- threshold of inclusion

- real threshold

2. Legal electoral thresholds

Electoral threshold

By natural threshold (TN) is meant the smallest share of votes for a given list (or a given candidate) in a set of validly cast votes in a district that guarantees that the list (or the candidate) receives at least one seat (or - no less than a specified number) with the known size of the electoral district and the electoral formula used, regardless of the distribution of votes in the given district.

Electoral threshold

The concept of this type of threshold is very close to the exclusion threshold (TE), which is a measure of "friendliness for minorities" of a given electoral system. However, unlike the postulated concept, the "exclusion threshold" assumes the intentional action of voters, informing about the minimum size of the group of voters who - using the right strategy - are able to get the desired result in obtaining at least one mandate by their preferred candidate (supported list ). In contrast, the nominal natural threshold does not assume intentional actions of voters or the adoption of a strategy by them. Relatively - it is assumed to adopt the least beneficial strategy from the point of view of a political group.

Electoral threshold

Therefore, the value of both thresholds brings different information, despite the fact that in most cases their value will be identical. The difference occurs in a situation in which voters, adopting the most favorable strategy for themselves, have greater opportunities than the parties (candidates) in the selection of the tools used.

Electoral threshold

This situation occurs in the case of the Limitet Vote majority rule, according to which voting takes place in multi-mandate constituencies, and each voter has a number of votes greater than 1, but smaller than the number of seats to be allocated in a district, but can not accumulate votes. The exclusion threshold will be G / (S + G), while the nominal natural threshold G / S + 1. This is due to the possibility of voters using a strategy in which each of them gives only one vote of several he has the right to.

Electoral threshold

Understanding the real natural threshold (TR) will be partly different. It should be understood as the smallest possible share of votes for a given list (or a given candidate) in a set of validly cast votes in a constituency, which allows to assume that a given list (or candidate) will obtain at least one mandate (or not less than a specified number of seats).

Electoral threshold

The real threshold is determined for the known size of the electoral district and the electoral formula used, taking into account the actual (imperfect) distribution of votes between the lists (or candidates), the discreet nature of seats and factors such as the number of lists participating in the distribution of seats in the district, anticipated the percentage of votes cast in the district into lists (candidates) not taking part in the distribution of seats, the expected percentage of votes cast in the district into groups with weak support - taking formal participation in the distribution of seats, but not having a real chance of getting them and others.

The significance of these factors depends on the elements of a particular electoral system.

Electoral threshold

If the nominal natural threshold is an unequivocal value and can be accurately calculated, the real natural threshold is the information burdened with the risk of mistake each time. In practical terms, especially when planning actions in the field of electoral engineering, the real electoral threshold is more important, because its level (and its correct estimation) influences the effectiveness of the adopted strategy by the political decision maker.

Electoral threshold

The difference between the nominal and real electoral threshold can also be explained using an example of the practice of functioning of various organizations in the electoral process:

imagine a situation in which a representative of the p olitical party asks: "what support the list (candidates) ) our organizations in each district should get, that we get at least one seat in each district? " In trying to answer such a question, it is necessary to have knowledge about the size of electoral districts and the electoral formula used.

Electoral threshold

With this data, you can give proper information in the form of a nominal natural threshold. For example, in the case of elections carried out according to the formula of proportional representation using the d'Hondt method in 5-seats constituances, the minimum support that lists must get in each district to be certain of obtaining a mandate (nominal natural threshold ) is 16.667%. This information is certainly important, but it may turn out to be insufficient. Practice indicates that a mandate may be obtained with 13,10%, 13.79% or 13.93% of valid votes in the constituency, which is 78.62% 82.72% and 83 , 57% of the face value of the natural threshold.

Electoral threshold

The nominal natural threshold is dependent on specific electoral methods.

TNd'H (Si) = Si / (S + 1)

TNS-L (Si) = (2Si-1) / (S + Si)

TNmod.S-L (Si) = (2 * Si-1) / [(2 * S1-1) + ((S-Si + 1) * 1.4)] Si> 1

TNH-N (Si) = [Si (S- (Si-1)) + (Si-1)] / [S (S + 2-Si)]

Electoral threshold

The value of the nominal natural threshold for the first mandate in the S-mandate district, in which L lists is allowed to participate in the distribution of seats depending on the electoral method used:

| d'Hondt | 1/(S+1) | ||

| Sainte-Laguë | 1/(2S-L+2) | L ≤ S+1 | |

| Mod. Sainte-Laguë (1,4) | 1,40/ [(2S-(L-1)+1,40)+(R*0,40)] |

L ≤ S+1 | R=2(L-1)-S dla L ≥ (S/2)+1 or R=0 for L<(S/2)+1 |

| Hare-Niemeyer | (L-1) / (L*S) | L ≤ S+1 |

Electoral threshold

Threshold of Inclusion otherwise defined by the representation threshold (TI).

Obtaining a number of votes smaller than TI makes it impossible to obtain even one mandate, even with the most favorable possible distribution of votes

Electoral threshold

Threshold of Inclusion otherwise defined by the representation threshold (TI).

| d'Hondt | 1 / (S+L-1) |

| Sainte-Laguë | 1 / (2S+L-2) |

| Mod. Sainte-Laguë (1,4) | 1,4 / (2S+1,4L-2,4) |

| Hare-Niemeyer | 1/(S*L) |

Electoral threshold

Threshold of Inclusion otherwise defined by the representation threshold (TI).

| FPTP used in SMC | 1/L |

| Party Block Vote | 1/L |

| SNTV | 1 vote |

| Block Vote | 1/L-S+1 |

| Limited Vote | 1 vote |

Electoral threshold

The presented values of the nominal natural threshold (threshold of exclusion) and the threshold of inclusion can be treated as border points on the axis determining the probability of obtaining a mandate - when vi = TI the probability is slightly above 0% (for vi = TI - 1 the chance is 0), while for vi = TN, the probability = 100%. The likelihood of gaining a seat will increase with retreat vi from TI, but more precise description is difficult due to its sensitivity to the specific distribution of votes in the district, and especially such elements as the number of votes cast on lists that did not exceed TI.

Electoral threshold

Looking for a value that could be an important piece of information, R. Taagepera, based on earlier studies by A. Lijphart, proposed the value of the average threshold, or the so-called effective threshold (meaning the last name seems to reflect its essence). According to his proposition, the effective TM threshold value is approximately 0.75 / (S + 1).

Electoral threshold

The effective threshold should be understood as the point where the chance to obtain a mandate is 50%. The logical consequence of this state is that exceeding TM means that the chance to obtain a mandate is (statistically) higher than the chance of not obtaining it. Applying this threshold in practice may be useful, but its usefulness is limited.

Electoral threshold

In addition to the natural thresholds resulting from the electoral structure and the electoral method adopted, the legal electoral threshold may be used.

In contrast to natural thresholds, the level of these thresholds and, consequently, their impact on the distribution of seats, depends directly on the political decision (in the case of natural thresholds, a similar relationship can be indicated, however, it is indirect).

The idea of electoral engineering

Electoral engineering should be understood as changes made in the electoral system that affect the electoral process at any stage, with the aim of changing the likelihood of obtaining a specific election result in line with the interests of the decision-maker, without directly affecting electoral decisions of voters regarding the election offer.

It may cause deformation of election results in relation to citizens' attitudes.

The idea of electoral engineering

Electoral engineering, as defined, has the following characteristics:

1. Is intentional The goal is to achieve a predetermined result:

- Elimination of specific candidates or parties from the election process.

- Increasing or decreasing the representation of a particular party in collegiate bodies.

- Increasing the probability of obtaining a specific personal composition of a given fraction in a collegial body.

- Increasing the likelihood of choosing a particular candidate or candidate representing a given party for a given function.

The idea of electoral engineering

2. It is a consequence of the decision-maker's interest or his perception of his own interest.

3. It affects the party system at various levels, and indirectly the political system. Directly shaping a political system should be considered as constitutional not electoral engineering.

The idea of electoral engineering

4. Electoral engineering may relate to various elements of the electoral process and its environment:

- Shaping the set of people with voting rights - both active and passive.

- The legal system of political parties.

- Determining the structure of constituencies.

- Catalog of entities authorized to submit candidates or lists of candidates.

-

Possibilities of interaction between entities submitting candidates or lists of candidates - e.g. grouping of lists.

The idea of electoral engineering

4. Electoral engineering may relate to various elements of the electoral process and its environment:

- The method of choice - direct, indirect.

- To apply a specific principle of representation - majority or proportional, and a specific electoral formula.

- Maintain the principle of effective equality of votes.

- To influence the perception of citizens and their ability to move inside the electoral process.

The idea of electoral engineering

5. It may apply to authorities at all levels:

- Central authority - in the case of Poland: the Sejm, Senate, President of the Republic of Poland.

- Local government bodies - legislative and executive bodies of communes, poviats, voivodships.

- Supranational institutions - this is a special case that applies due to Poland's membership in the European Union, and thus - elections to the European Parliament.

The idea of electoral engineering

7. It may be or is a disruption to the electoral process by:

- Obstructing the perception of the electoral process, including mainly the voter's understanding of the effect of the vote cast.

- Difficulties in the decision-making process of institutional participants of the election process - political parties, committees, etc.

- Distortion of the electoral offer presented to the voter.

- Excessive, unjustified deformation of election results in comparision to voting results.

The idea of electoral engineering

8. Can be analyzed due to:

- Impact on the party system.

- Realization of the goal set (if it is succesfull or not).

- The level of deformation relative to the adopted principle of representation .

- Impact on the social opinion of elected bodies .

The idea of electoral engineering

Electoral engineering in practice.

The idea of electoral engineering

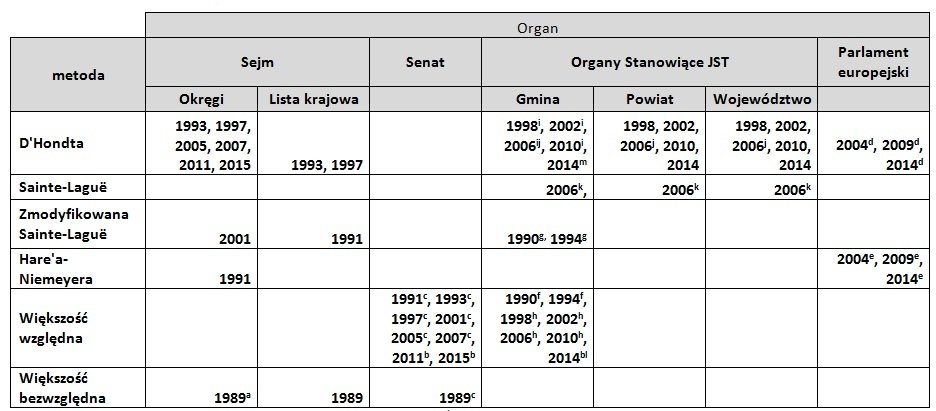

Electoral engineering in practice (electoral method 1989-2015).

The idea of electoral engineering

Electoral engineering in practice.

-

Prawo i Sprawiedliwość + Solidarna Polska + Porozumienie 44%

-

Koalicja Obywatelska: 30%

-

PLS+Kukiz’15: 14%

-

Lewica: 7%

-

Konfederacja: 5%

41 constituences (7-20 seats)

D't method

Legal threshold 5%/8%