Python from C

A gentle introduction to Python for C programmers

~ $ python

Python 3.3.0 (default, Dec 15 2012, 17:19:46)

[GCC 4.5.2] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> import ian

>>> help(ian)

Enough about me...

Help on module ian:

DESCRIPTION

Ian Cordasco

~~~~~~~~~~~~

- Developer at Bendyworks

- Open Source Lover

* Maintainer of Flake8 (python code-quality tool)

* Maintainer of Requests (python library for HTTP/1.1)

* Author of github3.py (wrapper around the GitHub API)

* Author of betamax (recording your HTTP interactions so the NSA doesn't have to)

* Author of uritemplate.py (implementation of RFC 6570)

* Contributor to lots of other stuff

- Python developer for the last 2 years

- C developer before that (still loves it)

lines 1-23/23 (END)Core Topics

- Type disciplines (which apply to C and which apply to Python)

- Duck typed

- Dynamically typed

- Statically typed

- Caveat into Exceptions

- Creating "full programs"

- Everything is an object

-

Creating your own objects

Type Disciplines

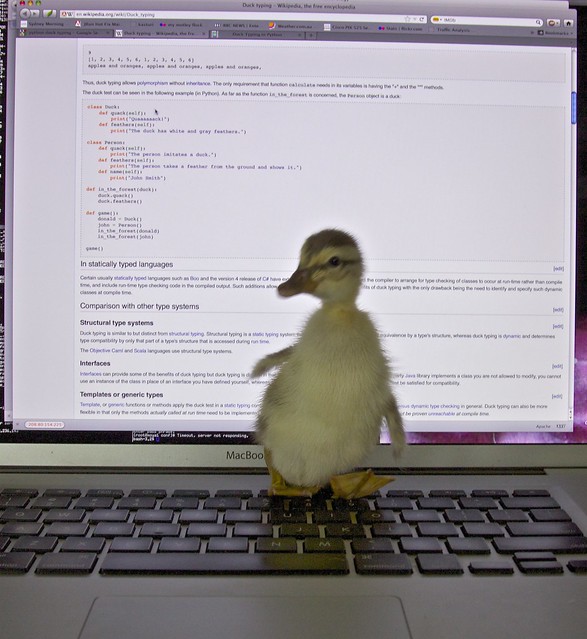

- Duck typed

- If it looks, acts, and sounds like a duck, it is most likely a duck.

- This applies to Python (and we'll see how soon)

- Strongly typed

- Interactions between types are well defined

- This applies to Python (not C)

- Statically typed

- Developers must specify the type they wish to use

- This applies to C

- Dynamically typed

- Developers do not have to specify the type they wish to use

- This applies to Python

And now for some examples

Hello World

In C

#include <stdio.h>

int main(char **argv, int argc){

puts("Hello World!\n");

return 0; /* Technically not even necessary anymore in C11 */

}In Python

print("Hello World!")Now that we have that out of the way

...

Something still trivial

But not exactly...

C

int add(int a, int b){

return a + b;

}

int main(void){ /* We're all adults here */

(void)add(1, 2);

(void)add(1, 'c');

(void)add(1, "characters");

return 0;

}Python

def add(a, b):

return a + b

add(1, 2)

add(1, "foo") # Wait, what?!What is actually happening here?!

Duck Typing

Duck Typing

In that code example:

def add(a, b):

return a + b

add(1, 2)

add(1, "foo")What is actually happening is something along these lines:

- 1 and 2 look and act alike. Let's try 1 + 2. Okay, we're good

- 1 and "foo" act alike (they can both be added). Let's try adding them.

The difference is that the second case will raise a TypeError

Some questions

- Will that C example ever run? (Hint: For the purpose of the example, I'm not using strict compilation flags)

- If it does, how?

- Does the Python example ever run?

- How does the Python example run?

Some answers

(I don't like suspense)

- The C example compiles and will run. (The third call to add will cause a warning on compilation.)

- It runs because of "weak" typing. (No don't start pressing your keys harder.)

- The Python example does run up until it encounters the TypeError

Exceptions

Let's look at that code example again

def add(a, b):

return a + b

add(1, "string")We see a TypeError in the console

~ $ python add.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "add.py", line 4, in <module>

add(1, "string")

File "add.py", line 2, in add

return a + b

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'We get the line numbers and an explanation of the exception

Exceptions cont'd

Our C example, when compiled provides

~ $ gcc add.c -o add

add.c: In function 'main':

add.c:10: warning: passing argument 2 of 'add' makes integer from pointer without a castWho said anything about pointers?

This is a common complaint among new programmers

But who said anything about new programmers?

(And who is dog?)

I did. Just now. Did you miss it?

Why I Like Exceptions

They make everything so accessible

- The exception

- triggers a full stack trace

- stops execution entirely

- provides a more intuitive message

- Standard compilation

- merely warns you

- compiles anyway

- assumes you know what you're doing

Program execution

In C#include <stdio.h>

int main(void){

printf("%d\n", 1 + 2);

return 0;

}

def main():

print("%d" % (1 + 2))Which one prints out 3?

How can I make Python work?

If you run the following instead

def main():

print("%d" % (1 + 2))

main()or even just

print("%d" % (1 + 2))you'll see 3 printed to the screen

Why?

Program Execution

- When the python interpreter opens a file it executes its contents

- If all you have are function definitions they are simply added to

the namespace - For something to happen you have to tell Python you want it

to happen - Canonical python script:

def function():

# This function does something

if __name__ == '__main__':

function()

__name__

- __name__ is a special variable set in each file

- Let's make the following files and run one of them:

- my_main.py:

import fake_module

if __name__ == '__main__':

print("From within my_main.py")

print("fake_module.__name__ = %s" % fake_module.__name__)

print("my_main.__name__ = %s" % __name__) - fake_module.py

print("From within fake_module.py")

print("fake_module.__name__ = %s" % __name__)

~ $ python my_main.py

From within fake_module.py

fake_module.__name__ = fake_module

From within my_main.py

fake_module.__name__ = fake_module

my_main.__name__ = __main__

__name__

- So everything in a python file is executed even on import

- That is, assuming it is not a function or class definition

- As is demonstrated flow-control statements are executed

(if, else, elif) - Loops will also be executed (while, for)

- Variables will be evaluated and assigned to

- Calls to functions, methods called on class instances,

and calls to class methods are all executed - Why? Because that's how Guido wanted it and he

is our Benevolent Dictator for Life (BDFL)

Everything is an Object

Seriously, even integers have methods

~ $ python

Python 3.3.0 (default, Dec 15 2012, 17:19:46)

[GCC 4.5.2] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> help(1)Help on int object:

class int(object)

| int(x[, base]) -> integer

|

| Convert a string or number to an integer, if possible. A floating

| point argument will be truncated towards zero (this does not include a

| string representation of a floating point number!) When converting a

| string, use the optional base. It is an error to supply a base when

| converting a non-string.

|

| Methods defined here:

|

| __abs__(...)

| x.__abs__() <==> abs(x)

|

| __add__(...)

| x.__add__(y) <==> x+y

...

Object-Oriented Programming

Everything has methods

So simple integer arithmetic can be written two ways:

1 + 1

1.__add__(1)

In Python, the obvious way is the right way

# |-1| == 1

assert abs(-1) == 1

assert (-1).__abs__() == 1

In many cases there are built-in functions that exist

simply to call methods on built-in objects.

Built-in Objects

- List

- Implementation: linked list

- Literal syntax "[1, 2, 3]"

- Dictionary (hash)

- Implementation: unordered hash

- Literal syntax "{'key': 'value'}"

- Tuples

- "Implementation": fixed-size array

- Literal syntax "(1, 2, 3)"

- Sets

- Literal syntax "{1, 2, 3,}"

- Strings, Bytearrays

- Integers, Complex numbers, floats

Example Usage

a = [1, 2, 3]

print(a[0]) # prints 1

print(a[-1]) # prints 3

print(a[-3]) # prints 1

a.append(4)

print(a[-1]) # prints 4

a[2] = 10

b = {1: 2, 'key': 'value'}

print(b[1]) # prints 2

print(b['key']) # prints value

b['new key'] = 'new value'

c = {1, 2, 3, 4}

d = {5, 6, 7, 8}

print(c.union(d)) # prints {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}e = (1, 2, 3)

print(e[0]) # prints 1

print(e[-1]) # prints 3

f = 'string'

print(f[0]) # prints s

print(f[0:3]) # prints str

g = 1 + 1j # Yay for Electrical Engineers -_-

print(1 + g) # prints (2+1j)

print(1j + g) # prints (1+2j)

Iteration

List iterations in C and Python

Rough C:

for (t_node node = list->head; node; node = node->next) {

dump_node(node);

}Python:

l = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

for i in l:

print(i)

Uhm, what?

- Lists, sets, tuples, dictionaries, & strings can all be iterated over

- Lists, sets, and tuples iterate on items

- Dictionaries iterate on keys

- Strings iterate on "characters"

for item in [1, 2, 3]: # prints "1 2 3"

print(item, end=' ')

d = {'key0': 'value0', 'key0': 'value0'} for item in d: # prints "key1 => value1 key0 => value0"

print("%s => %s" % (item, d[item]), end=" ")

for c in 'this is a string': # prints "t h i s i s a s t r i n g"

print(c, end=" ")

This last one, most people despise

Iteration vs Canonical C

Arrays

Let's assume arrays are like tuples

int[10] a = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10};

int i = 0;

for (; i < 10; i++) {

printf("%d ", a[i]);

}

a = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

i = 0

while i < 10:

print(a[i], end=" ")

i += 1vs

a = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

for i in a:

print(i, end=" ")Bye, bye loop counter. I shall miss you.

Quick Note on Slicing

a = "string foo bar"

print(a[:6]) # prints string

print(a[0:6])

print(a[7:10]) # prints foo

print(a[11:]) # prints bar

b = [1, 2, 3, 4]

assert b[:3] == [1, 2]

assert b[2:] == [2, 3, 4]

Slices seem like magic but they're awesome

Unfortunately they're a bit beyond the scope of this talk

But after the next topic I can discuss them a bit if I have time

Creating Your Own Objects

In C:

/* user.h */

typedef struct { /* We're all good citizens who use typedefs, right? */

int id;

char* login;

char* real_name;

/* ... */

} t_gh_user;

t_gh_user* gh_new_user(int, char*, char*, /* ... */);

int gh_update_user(t_gh_user, char*, char*, /* ... */);

/* And many more "methods" */In Python:

class User(object):

def __init__(self, id, login, real_name,

# ...

):

self.id = id

self.login = login

# ...

def update(self, # ...

):

# ...

Objects, cont'd

Making and manipulating objects

In C:

t_gh_user* u = gh_new_user(1, "mojombo", "Tom Preston Warner", /* ... */);

if (!gh_update_user(u, "Tom Preston (the Awesome) Warner", /* ... */) {

error("We can not update mojombo's profile! Abort! Abort!");

}In Python:

u = User(login="mojombo", id=1, real_name="Tom Preston Warner", #...

)

try:

u.update(real_name="Tom Preston (the Awesome) Warner", #...

)

except Exception:

error("We can not update mojombo's profile! Abort! Abort!)

But what is __init__?!

-

__init__ - is a method on an object

- is not a constructor

- is an initializer

- is called to initialze an instantiated object

- You might notice that

__init__'s first parameter isself - This is the object that was constructed

- We then set attributes on

self - We never return

self.

Where are the clowns?

I meant to say constructors

You should never need to see them

See possible up-coming talk on metaprogramming in Python

This may or may not be a vision test

Thanks!

@sigmavirus24

(Twitter, GitHub, StackOverflow)