Fun with arrows

Marcin Rzeźnicki

Scala Animal

mrzeznicki@iterato.rs

FUN WITH ARROWS

- https://github.com/VirtusLab/kleisli-examples

- http://virtuslab.com/blog/arrows-monads-and-kleisli-part-i/

- http://virtuslab.com/blog/arrows-monads-and-kleisli-part-ii/

PROBLEM

Logika biznesowa napisana w "Scavie" - Java z trochę innymi słowami kluczowymi. Zazwyczaj:

- imperatywny

- komunikacja poprzez wyjątki

- Unit

- zerowe możliwości kompozycji

Logika utopiona w kodzie - niewidoczny flow (nawet jeżeli kod nie jest fatalny)

ANEGDOTA

Dostałem taki komentarz:

I know this is a bit of a religious thing in FP, but personally I don't think there is anything wrong with throwing exceptions. Of all the problems I have encountered in the years of programming, having to deal with exceptions and throwing exceptions was never a core problem. Throwing and catching exceptions is well defined even if it escapes explicit/compile-time types (so is pattern matching).

PROBLEM

Realistyczny przykład takiego stylu (to kiedyś był prawdziwy kod produkcyjny)

Jeśli chcemy używać FP, tego typu API nie ma sensu

WYMAGANIA

- walidacja

- brak wyjątków

- logowanie

- rozgałęzienia w logice

Chcemy nie tylko wyeliminować problemy - ale również zmienić kod na czysto funkcyjny

WYMAGANIA - WALIDACJA

- załóżmy, że nie możemy dokonać żadnej modyfikacji jeśli status ustawiony jest na Done

- nieuchronny copy-paste (?)

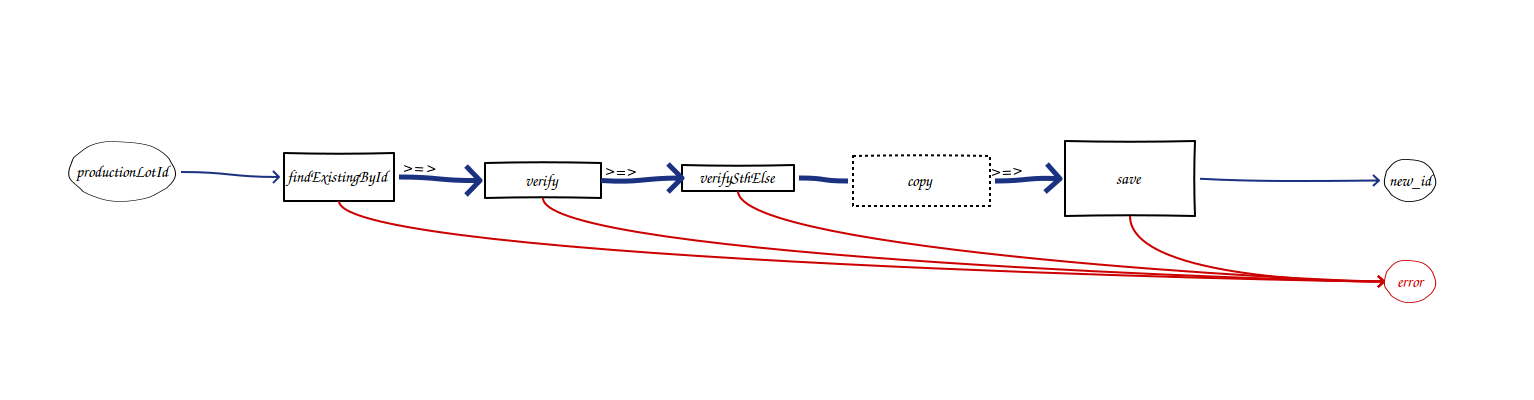

OBSERWACJE

Wszystkie metody napisane są wg tego samego wzorca: pobierz dane z bazy, sprawdź poprawność, zmodyfikuj encję, zapisz do bazy.

Czy kompozycja funkcji będzie w sam raz? Każda metoda może być przepisana jako: getFromDb andThen verify andThen copy andThen save.

Pozostaje problem z unit oraz wyjątki - potrzeba potężniejszej abstrakcji

INSPIRACJE

- Railway Oriented Programming (http://fsharpforfunandprofit.com/rop/)

- talk na Scala Days (https://www.parleys.com/tutorial/functional-programming-arrows)

STRZAŁKI - DEFINICJE

Wikipedia:

Arrows are a type class used in programming to describe computations in a pure and declarative fashion. [Arrows] provide a referentially transparent way of expressing relationships between logical steps in a computation. Unlike monads, arrows don’t limit steps to having one and only one input.

STRZAŁKI - DEFINICJE

Haskell wiki:

Arrow a b c represents a process that takes as input something of type b and outputs something of type c.

W praktyce: można rozumieć strzałki jako typ rozszerzający funkcję (=>) o dodatkowe kombinatory (poza compose i andThen)

Komponowanie strzałek jest bardziej ekspresywne i może zawierać bogatą semantykę np. komponowanie obliczeń monadycznych

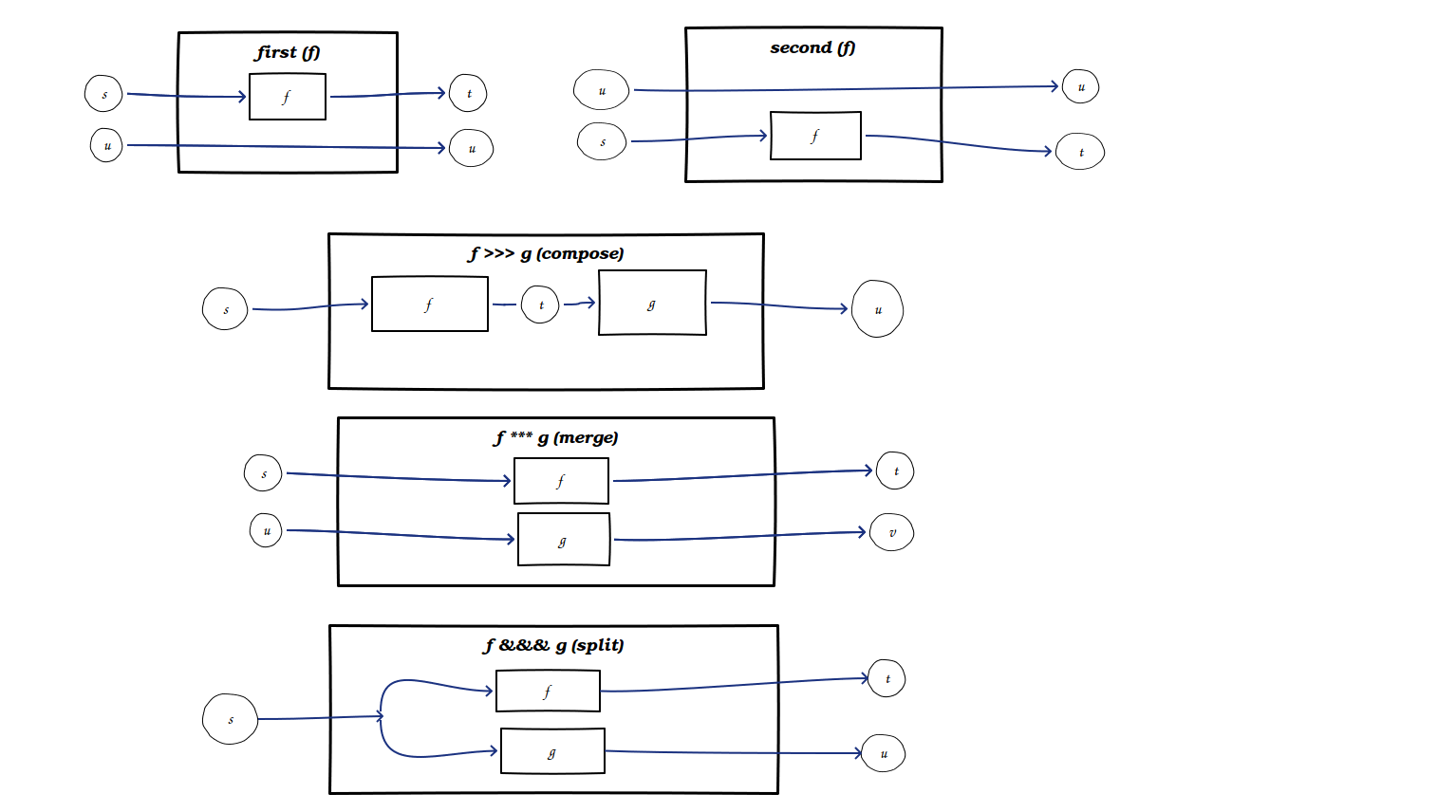

STRZAŁKI - INTERFEJS

- arr (s -> t) -> A s t

- first (A s t) -> A (s,u) (t,u) / second (A s t) -> A (u, s) (u, t)

- kompozycja: A s t >>> A t u -> A s u

- scalenie: A s t *** A u v -> A (s,u) (t,v)

- rozdzielenie: A s t &&& A s u -> A s (t, u)

STRZAŁKI - INTERFEJS

trait Arrow[=>:[_, _]] {

def id[A]: A =>: A

def arr[A, B](f: A => B): A =>: B

def compose[A, B, C](fbc: B =>: C, fab: A =>: B): A =>: C

def first[A, B, C](f: A =>: B): (A, C) =>: (B, C)

def second[A, B, C](f: A =>: B): (C, A) =>: (C, B)

def merge[A, B, C, D](f: A =>: B, g: C =>: D): (A, C) =>: (B, D) =

compose(first(f), second(g))

def split[A, B, C](fab: A =>: B, fac: A =>: C): A =>: (B, C) =

compose(merge(fab, fac), arr((x: A) => (x, x)))

}KOCHAMY SYMBOLICZNE OPERATORY

final class ArrowOps[=>:[_, _], A, B](val self: A =>: B)(implicit val arr: Arrow[=>:]) {

def >>>[C](fbc: B =>: C): A =>: C = arr.compose(fbc, self)

def <<<[C](fca: C =>: A): C =>: B = arr.compose(self, fca)

def ***[C, D](g: C =>: D): (A, C) =>: (B, D) = arr.merge(self, g)

def &&&[C](fac: A =>: C): A =>: (B, C) = arr.split(self, fac)

}

KOCHAMY SYMBOLICZNE OPERATORY ?

Part of my problem with Arrows is the names most people give the functions. andThen and orElse I understand; their names reflect their meaning in some way. *** and &&& not so much.

Interesting read, except for accumulating =>:, >>>, <<<, ***, &&&, >>=, >=>, >==>, <=<, <==<. Looks like ancient sbt to me ;)

KOCHAMY SYMBOLICZNE OPERATORY !

Yeah, well, there are two camps of thought on symbolic operator. It's love or hate, nothing in between :-) I tend to like them because they're concise, but I totally understand people who find them cryptic. At least one could argue that things like '***' have somewhat established meaning and that helps to avoid cognitive overload, don't they?

I have no objection to both being available.

FUNKCJA TO STRZAŁKA

implicit object FunctionArrow extends Arrow[Function1] {

override def id[A]: A => A = identity[A]

override def arr[A, B](f: (A) => B): A => B = f

override def compose[A, B, C](fbc: B => C, fab: A => B): A => C =

fbc compose fab

override def first[A, B, C](f: A => B): ((A, C)) => (B, C) = prod =>

(f(prod._1), prod._2)

override def second[A, B, C](f: A => B): ((C, A)) => (C, B) = prod =>

(prod._1, f(prod._2))

override def merge[A, B, C, D](f: (A) => B, g: (C) => D): ((A, C)) => (B, D) = {

case (x, y) => (f(x), g(y))

}

}

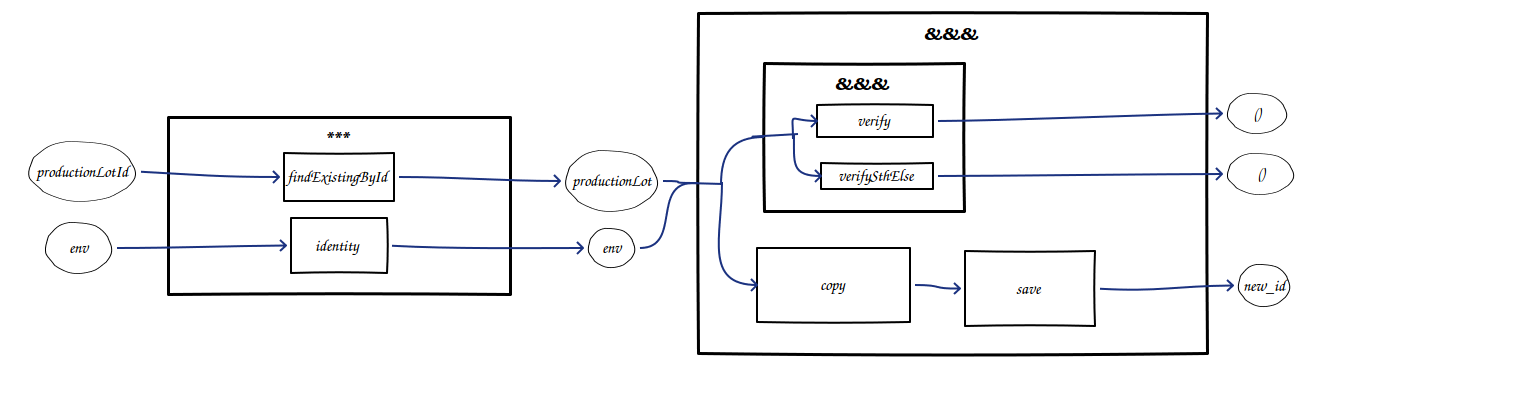

FLOW

WYMAGANIE-WALIDACJA

private def productionLotArrow[Env](verify: (ProductionLot, Env) => Unit,

copy: (ProductionLot, Env) => ProductionLot):

(Long, Env) => Long = {

val verifyProductionLotNotDoneF: ((ProductionLot, Env)) => Unit = {

case (pl, _) => verifyProductionLotNotDone(pl)

}

Function.untupled(

(productionLotsRepository.findExistingById _ *** identity[Env])

>>> ((verify.tupled &&& verifyProductionLotNotDoneF)

&&& (copy.tupled >>> productionLotsRepository.save))

>>> (_._2)

)

}

private def verifyProductionLotNotDone(productionLot: ProductionLot): Unit =

require(productionLot.status != ProductionLotStatus.Done,

"Attempt to operate on finished production lot")

ANEGDOTA

Kolejny komentarz:

And so it happens that the original half-functional code looks the most readable and easy to grasp version. And yeah, I can copy and paste that to insert another verification…

WYJĄTKI = EITHER

Obsługa błędów staje się częścią control flow.

Umożliwia bycie type-safe, pure etc. mimo przykrej konieczności obsługiwania błędów.

Przepiszmy wszystkie miejsca gdzie chcemy "rzucić" wyjątek z użyciem Either.

Możemy stworzyć ADT do reprezentowania różnych przypadków

WYJĄTKI = EITHER

sealed abstract class Error(val message: String)

case class ProductionLotNotFoundError(id: Long) extends

Error(s"ProductionLot $id does not exist")

case class ProductionLotClosedError(pl: ProductionLot) extends

Error(s"Attempt to operate on finished ProductionLot $pl")

case class NoWorkerError(pl: ProductionLot) extends

Error(s"No worker has been assigned to $pl")

case class SameWorkerError(pl: ProductionLot) extends

Error(s"Illegal worker reassignment $pl")

case class WorkerAlreadyAssignedError(pl: ProductionLot) extends

Error(s"Worker already assigned: $pl")

class ProductionLotsRepository {

def findExistingById(productionLotId: Long): Either[Error, ProductionLot] =

findById(productionLotId).toRight(ProductionLotNotFoundError(productionLotId))

def findById(productionLotId: Long): Option[ProductionLot] = ???

def save(productionLot: ProductionLot): Either[Error, Long] = ???

}WYJĄTKI = EITHER

class ProductionLotsService {

//...

private def verifyProductionLotNotDone(productionLot: ProductionLot):

Either[Error, ProductionLot] =

Either.cond(productionLot.status != ProductionLotStatus.Done,

productionLot,

ProductionLotClosedError(productionLot))

private def verifyWorkerChange(productionLot: ProductionLot, newWorkerId: Long):

Either[Error, ProductionLot] =

productionLot.workerId.fold[Either[Error, ProductionLot]](

Left(NoWorkerError(productionLot)))(

workerId => Either.cond(workerId != newWorkerId,

productionLot,

SameWorkerError(productionLot)))

private def verifyWorkerCanBeAssignedToProductionLot(productionLot: ProductionLot, workerId: Long):

Either[Error, ProductionLot] =

Either.cond(productionLot.workerId.isEmpty,

productionLot,

WorkerAlreadyAssignedError(productionLot))

}OBSERWACJE

Strzałka się nie kompiluje :-(

Nie ma tego jak naprawić, bo kompozycja funkcji zwracających Either jest średnio wykonalna (każda składowa funkcja musiałaby umieć "odpakować" rezultat z Either - masa boilerplate'u).

Monads do not compose

OBSERWACJE

Abstrakcja strzałki jest w stanie wyrazić wiele "typów" obliczeń. Nie ma żadnych ograniczeń co do typów na jakich operujemy - musimy umieć tylko wyrazić obliczenia na tych typów za pomocą kombinatorów first/second oraz compose

Funkcje A => B są ewidentnie niewystarczające w obliczu monady, ale istnieją inne abstrakcje, w których monadyczne obliczenie jest łatwo wyrażalne.

Są one znane jako ...

STRZAŁKI KLEISLIEGO

Mówiąc językiem Scali:

Strzałki Kleisliego są implementacją klasy typów (typeclass) strzałek w oparciu o funkcje A => M[B], gdzie M jest instancją monady

STRZAŁKI KLEISLIEGO

final case class Kleisli[M[_], A, B](run: A => M[B]) {

import Monad._

import Kleisli._

def apply(a: A) = run(a)

def >=>[C](k: Kleisli[M, B, C])(implicit m: Monad[M]): Kleisli[M, A, C] =

Kleisli((a: A) => this(a) >>= k.run)

def andThen[C](k: Kleisli[M, B, C])(implicit m: Monad[M]): Kleisli[M, A, C] = this >=> k

def >==>[C](k: B => M[C])(implicit m: Monad[M]): Kleisli[M, A, C] = this >=> Kleisli(k)

def andThenK[C](k: B => M[C])(implicit m: Monad[M]): Kleisli[M, A, C] = this >==> k

def <=<[C](k: Kleisli[M, C, A])(implicit m: Monad[M]): Kleisli[M, C, B] = k >=> this

def compose[C](k: Kleisli[M, C, A])(implicit m: Monad[M]): Kleisli[M, C, B] = k >=> this

def <==<[C](k: C => M[A])(implicit m: Monad[M]): Kleisli[M, C, B] = Kleisli(k) >=> this

def composeK[C](k: C => M[A])(implicit m: Monad[M]): Kleisli[M, C, B] = this <==< k

def map[C](f: B ⇒ C)(implicit m: Monad[M]): Kleisli[M, A, C] = Kleisli((a: A) => m.fmap(this(a))(f))

}

object Kleisli extends KleisliInstances {

implicit def kleisliFn[M[_], A, B](k: Kleisli[M, A, B]): (A) ⇒ M[B] = k.run

}STRZAŁKI KLEISLIEGO

//kleisli (a => m b) is arrow

abstract class KleisliArrow[M[_]] extends

Arrow[({ type λ[α, β] = Kleisli[M, α, β] })#λ] {

import Kleisli._

import Monad._

implicit def M: Monad[M]

override def id[A]: Kleisli[M, A, A] = Kleisli(a => M.point(a))

override def arr[A, B](f: (A) => B): Kleisli[M, A, B] =

Kleisli(a => M.point(f(a)))

override def first[A, B, C](f: Kleisli[M, A, B]): Kleisli[M, (A, C), (B, C)] = Kleisli {

case (a, c) => f(a) >>= ((b: B) => M.point((b, c)))

}

override def second[A, B, C](f: Kleisli[M, A, B]): Kleisli[M, (C, A), (C, B)] = Kleisli {

case (c, a) => f(a) >>= ((b: B) => M.point((c, b)))

}

override def compose[A, B, C](fbc: Kleisli[M, B, C], fab: Kleisli[M, A, B]): Kleisli[M, A, C] =

fab >=> fbc

}

implicit def kleisliArrow[M[_]](implicit m: Monad[M]) = new KleisliArrow[M]

override implicit def M: Monad[M] = m

}SCALA WOES

Either w scala.util nie jest monadą:

- brak tzw. biasu

- type kind monady to * -> *, Either : * -> * -> * (w Scali, w przeciwieństwie do np. Haskella nie ma curryingu na poziomie konstruktora typu)

OBSERWACJE

Wprawdzie scala.util.Either nie jest monadą, ale bardzo łatwo można to naprawić odpowiednio implementując instancję klasy typów (albo używamy scalaz). Oba problemy załatwiamy za jednym posunięciem:

implicit def eitherMonad[L] = new Monad[({ type λ[β] = Either[L, β] })#λ] {

override def point[A](a: => A): Either[L, A] = Right(a)

override def bind[A, B](ma: Either[L, A])(f: (A) => Either[L, B]): Either[L, B] =

ma.right.flatMap(f)

override def fmap[A, B](ma: Either[L, A])(f: (A) => B): Either[L, B] =

ma.right.map(f)

}

SCALA WOES

Type lambdy

- piekielna składnia:

- Type lambdas are cool and all, but not a single line of the compiler was ever written with them in mind. They’re just not going to work right: the relevant code is not robust.

implicit def ToArrowOpsFromKleisliLike[G[_], F[G[_], _, _], A, B](v: F[G, A, B])(implicit

arr: Arrow[({ type λ[α, β] = F[G, α, β] })#λ]) =

new ArrowOps[({ type λ[α, β] = F[G, α, β] })#λ, A, B](v)

OBSERWACJE

Składnię można naprawić, dzięki projektowi kind-projector. Polecany plugin do kompilatora, dla lubiących "zabawę z typami":

- implicit def eitherMonad[L] = new Monad[({ type λ[β] = Either[L, β] })#λ] {

+ implicit def eitherMonad[L] = new Monad[Either[L, ?]] {

FLOW Z WYJĄTKAMI

WYMAGANIE - WYJĄTKI

type E[R] = Either[Error, R]

private def productionLotArrow[Env](verify: (ProductionLot, Env) => E[ProductionLot],

copy: (ProductionLot, Env) => ProductionLot):

Env => Long => E[Long] = {

val verifyProductionLotNotDoneF: (ProductionLot) => E[ProductionLot] =

verifyProductionLotNotDone

(env: Env) => (

Kleisli[E, Long, ProductionLot]{ productionLotsRepository.findExistingById }

>>> Kleisli { verify(_, env) }

>>> Kleisli { verifyProductionLotNotDoneF }

).map(copy(_, env)) >==> productionLotsRepository.save _

}

+ MAŁY REFACTOR

private def productionLotArrow[Env](verify: (ProductionLot, Env) => Either[Error, ProductionLot],

copy: (ProductionLot, Env) => ProductionLot):

Env => Long => Either[Error, Long] = {

type Track[T] = Either[Error, T]

def track[A, B](f: A => Track[B]) = Kleisli(f)

val getFromDb = track { productionLotsRepository.findExistingById }

val validate = (env: Env) => track { verify(_: ProductionLot, env) }

>>> track { verifyProductionLotNotDone }

val save = track { productionLotsRepository.save }

(env: Env) => (

getFromDb

>>> validate(env)

).map(copy(_, env)) >>> save

}

SCALA WOES

SI-2712 - bug, którego numer pamiętam:

-

czemu musimy używać aliasu Kleisli[Track, A, B]?

-

[error] — because — [error] argument expression’s type is not compatible with formal parameter type; [error] found : org.virtuslab.blog.kleisli.ProductionLot => Either[org.virtuslab.blog.kleisli.Error,org.virtuslab.blog.kleisli.ProductionLot] [error] required: ?A => ?M[?B]

SCALA WOES

SI-2712 - bug, którego numer pamiętam:

-

to czemu nie napisaliśmy np. Kleisli[Either[Error, ?], Long, ProductionLot]? -

[info] — because — [info] argument expression’s type is not compatible with formal parameter type; [info] found : org.virtuslab.blog.kleisli.Kleisli[[R]scala.util.Either[org.virtuslab.blog.kleisli.Error,R],Long,org.virtuslab.blog. kleisli.ProductionLot] [info] required: ?F[?G, ?A, ?B]

SCALA WOES

SI-2712 - bug, którego numer pamiętam:

-

ale przecież istnieje unifikacja! F[_, _, _] / Kleisli, G[_] / [R]scala.util.Either[org.virtuslab.blog.kleisli.Error,R], A / Long, B/ ProductionLot

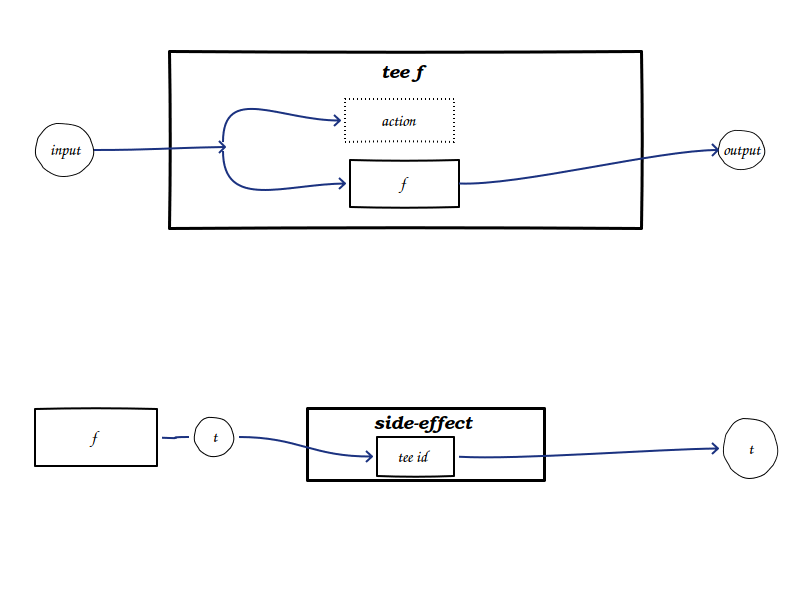

WYMAGANIE - LOGOWANIE

Problematyczna operacja z funkcjonalnego punktu widzenia:

- String => Unit - nie ma użytecznej wartości zwracanej, side-effect

- musimy wprowadzić możliwość zrobienia "reroutingu" flow "wokół" tego typu funkcji (dead-end)

WYMAGANIE - LOGOWANIE

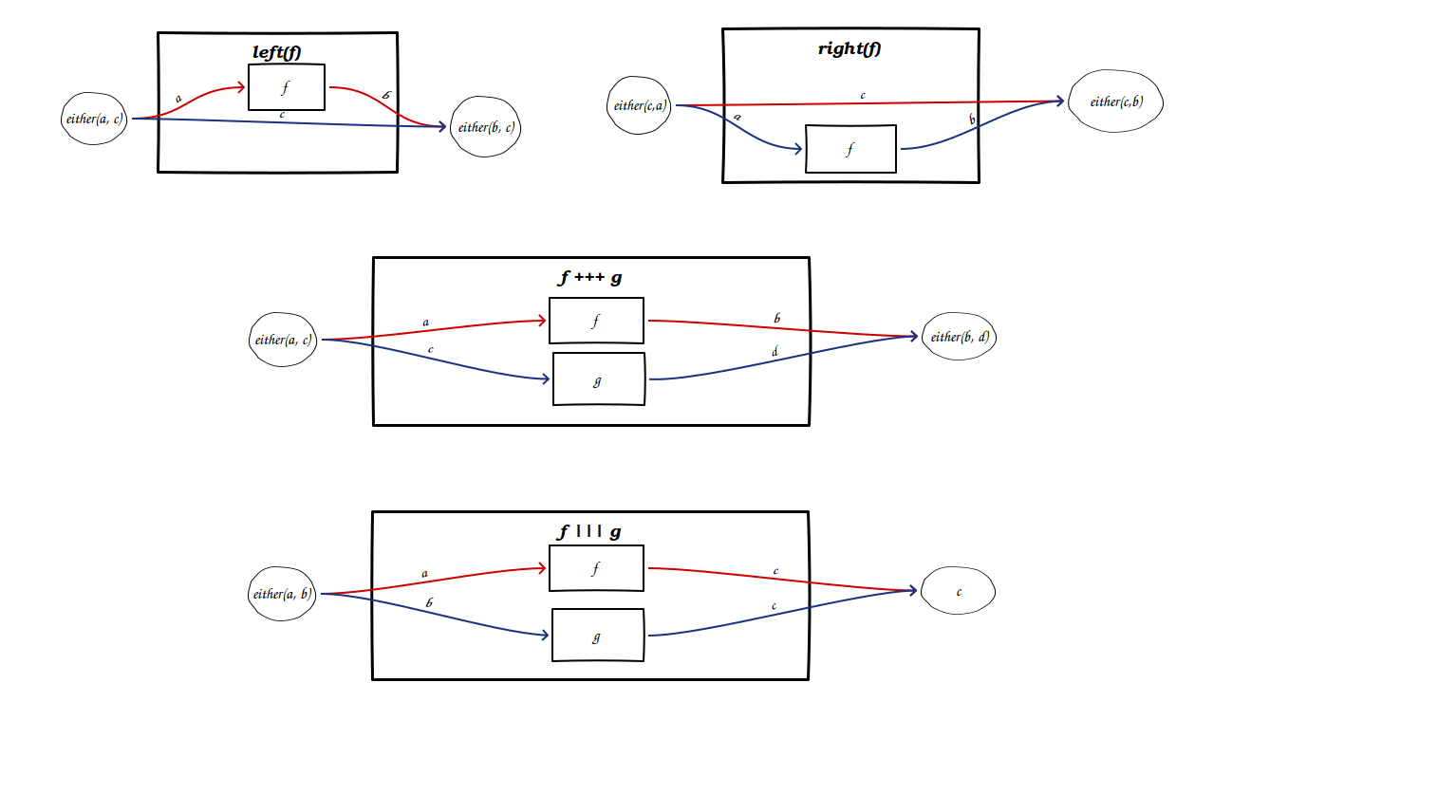

WYBÓR

Strzałka wyboru: ekwiwalent if w for-comprehension.

Dodatkowe kombinatory:

- left - ekwiwalent LeftProjection na Either

- right

- +++

- |||

WYBÓR

WYBÓR

Przykładowa implementacja strzałki wyboru dla funkcji

implicit object FunctionArrow extends Arrow[Function1] with Choice[Function1] {

// ...

override def left[A, B, C](f: (A) => B): (Either[A, C]) => Either[B, C] =

_.left.map(f)

override def right[A, B, C](f: (A) => B): (Either[C, A]) => Either[C, B] =

_.right.map(f)

override def multiplex[A, B, C, D](f: (A) => B, g: (C) => D):

(Either[A, C]) => Either[B, D] = {

case Left(a) => Left(f(a))

case Right(c) => Right(g(c))

}

override def fanin[A, B, C](f: (A) => C, g: (B) => C): (Either[A, B]) => C =

_.fold(f, g)

}

WYMAGANIA

private val logger = Logger.getLogger(this.getClass.getName)

private def productionLotArrow[Env](verify: (ProductionLot, Env) => Either[Error, ProductionLot],

copy: (ProductionLot, Env) => ProductionLot,

log: (ProductionLot, Env) => Unit):

Env => Long => Either[Error, Long] = {

type Track[T] = Either[Error, T]

def track[A, B](f: A => Track[B]) = Kleisli[Track, A, B](f)

val getFromDb = track { productionLotsRepository.findExistingById }

val validate = (env: Env) => track { verify(_: ProductionLot, env) }

>>> track { verifyProductionLotNotDone }

val save = track { productionLotsRepository.save }

val logError: Error => Unit = error =>

logger.warning(s"Cannot perform operation on production lot: $error")

val logSuccess: Long => Unit = id =>

logger.fine(s"Production lot $id updated")

(env: Env) =>

((

getFromDb -| (log(_, env))

>>> validate(env)).map(copy(_, env))

>>> save)

.run -| (logError ||| logSuccess)

}

DALSZE PRACE

- Różne monady - naturalna transformata, lifting (GitHub)

- Eliminacja explicit env - Reader monad + EitherT, transformatory strzałek

- Stworzenie biblioteki

DZIĘKUJĘ