Euler's fundamental discoveries about the exponential function: Their role in quantum computing

Marek Gluza

NTU Singapore

Click links at slides.com/marekgluza

Outline:

- Infinite sums

- Euler's formula

- Infinite products

Read Euler - he is the master of us all.

- Pierre-Simon Laplace

Sums and infinite sums

In times of Euler, mathematics was an experimental science:

What will be the value of \(S_\infty\)?

Will it exceed \(S_\infty>2\)?

Sums and infinite sums

Let us use a trick:

Euler (and later Ramanujan) was famous for playing with infinite sums. This trick works but Euler made mistakes too. Generations of mathematicians after him had to provide a proof that his intuition was correct.

Sums and infinite sums

Check: \(S_\infty(q=1/2) = 1 / (1-1/2) =2\)

The exponential function

Above, \(|q|<1\) was a restriction. Here \(1/n!\) coefficients remove the restriction and \(x\in \mathbb R\) can be arbitrary.

We understood \(q\in \mathbb C\). What if \(q\) was a matrix?

Check: It makes sense to ask this because if \(A\in \mathbb C ^{d\times d} \) then \(A^k\in \mathbb C ^{d\times d} \) and we can add matrices of the same dimension.

Quantum mechanics

used to be called matrix mechanics

Matrix inversion?!

Quantum mechanics

is all about exponentials

If \(A\in \mathbb C ^{n\times n} \) then we can define the exponential:

It means: multiply the matrix with itself \(n\) times and sum it up with the coefficient \(1/n!\)

I cannot draw a picture of \(e^A\) like for \(e^x\). But I will show you why choosing \(A\) to be \(A = \begin{pmatrix} 0 &1\\-1 & 0\end{pmatrix}\) is useful in quantum computing.

It means: multiply the matrix with itself \(n\) times and sum it up with the coefficient \(1/n!\) (this was missing before).

Outline:

- Infinite sums

- Euler's formula

- Infinite products

Euler was studying complex numbers:

\(z = x+iy\) where \(x,y\in \mathbb R\) and \(i^2 = -1\)

He asked: What would be the exponential of a purely complex number \(e^{z} = e^{iy}\)?

Euler wrote 800 manuscripts in his life, they included many formulas.

But what he found here is usually called the Euler's formula.

Euler was studying complex numbers:

\(z = x+iy\) where \(x,y\in \mathbb R\) and \(i^2 = -1\)

He asked: What would be the exponential of a purely complex number \(e^{z} = e^{iy}\)?

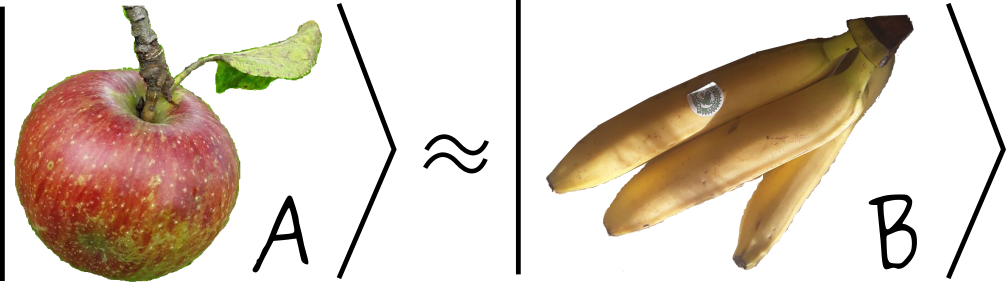

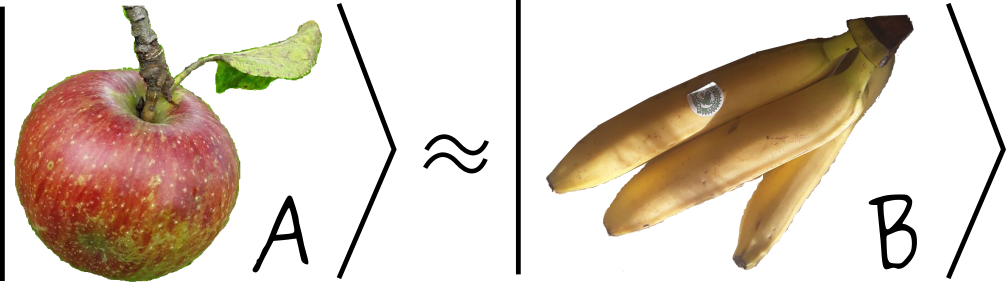

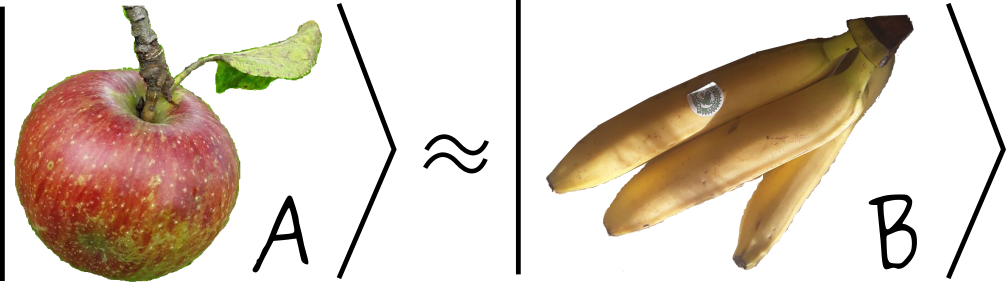

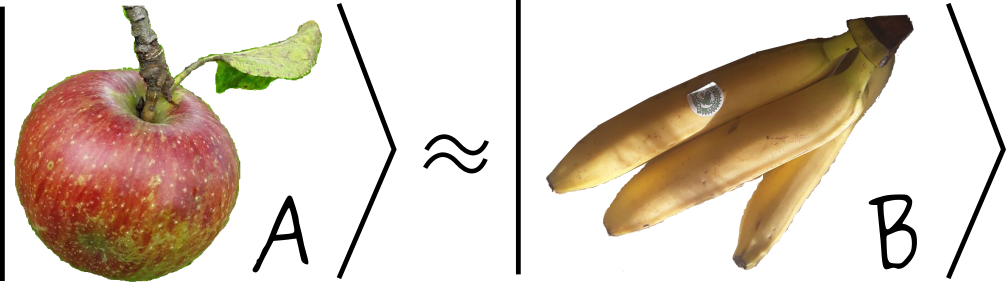

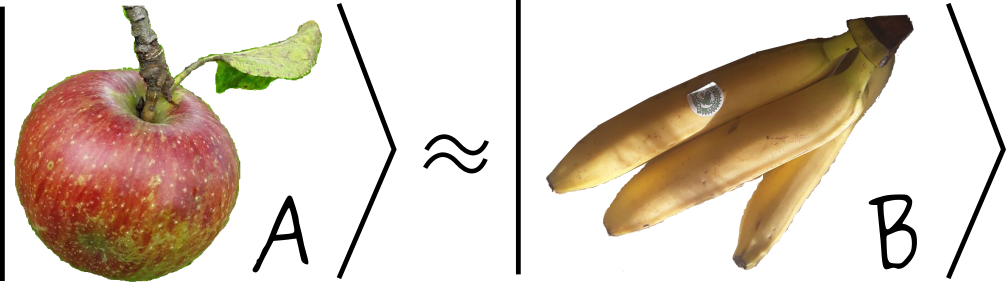

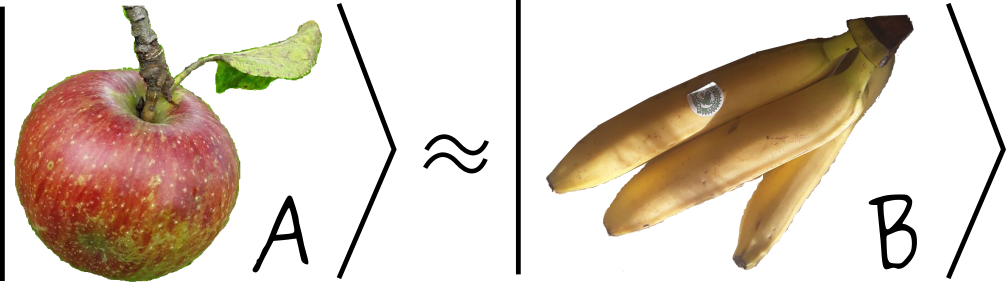

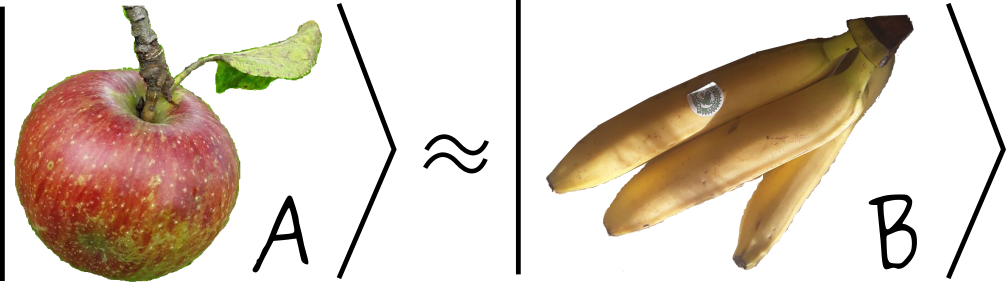

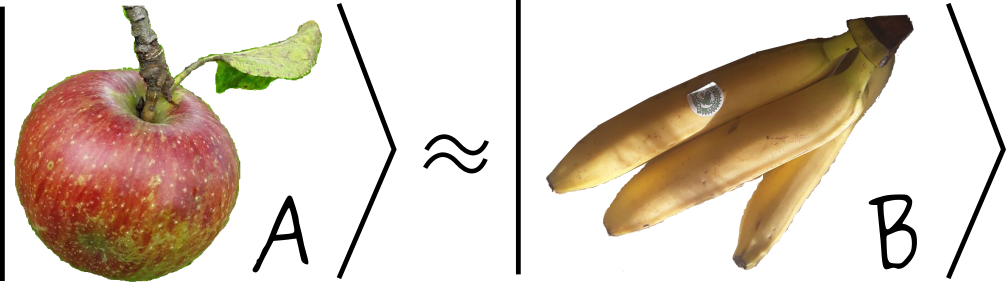

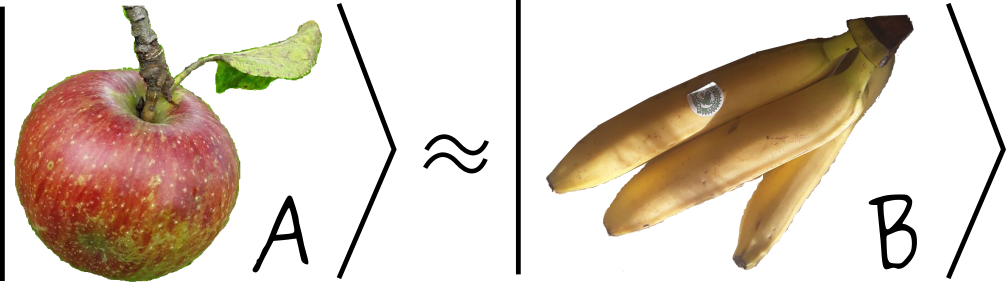

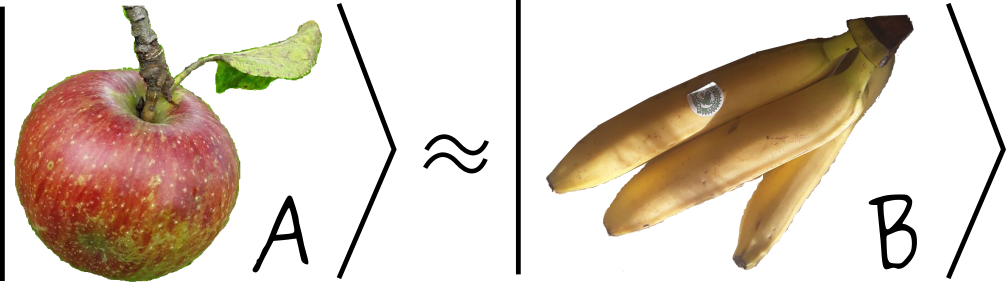

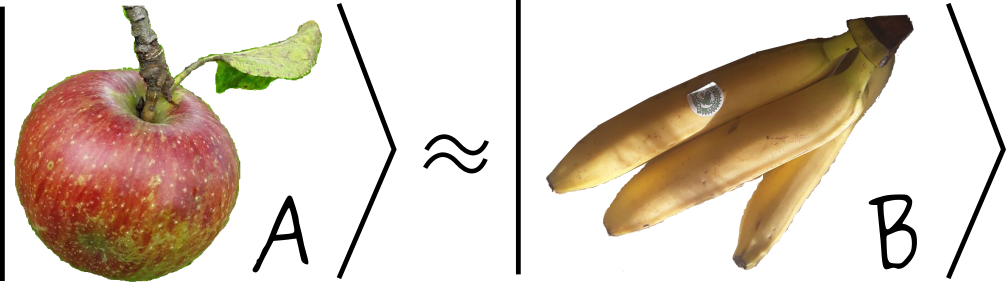

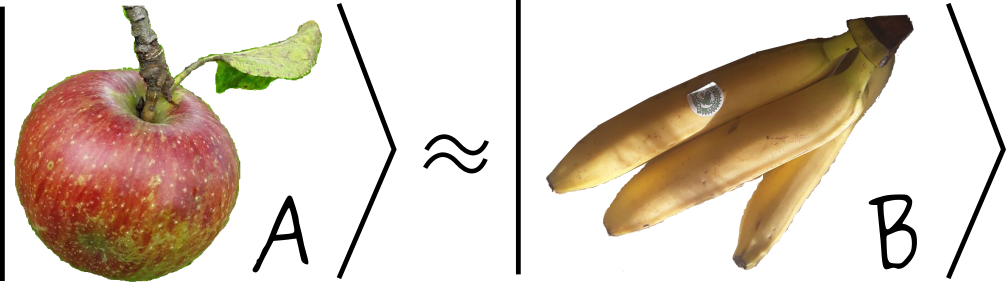

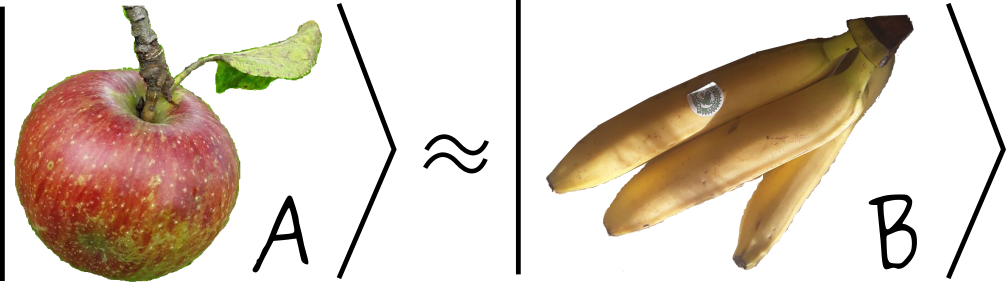

Braket notation

"ket"

"quantum superposition"

In quantum computing, the state of a single qubit is a 2-dimensional vector \(\ket\psi = a \ket{0} +b\ket{1}\).

An operation with duration \(t\) and generated by \(Y=Y^\dagger \in\mathbb{C}^{2\times 2}\) is given by

Quantum computing operation a qubit is given by multiplying a 2-dimensional matrix to that vector.

"quantum evolution"

How can we create \( \frac1 {\sqrt 2} \ket{0} +\frac 1 {\sqrt 2}\ket{1}\)?

It has the properties

\(Y^2 = I\) and \(Y\ket 0 = - i \ket 1\)

Let us study the matrix \(Y = \begin{pmatrix} 0 &-i\\i & 0\end{pmatrix}\)

It can be engineered by applying oscillatory electromagnetic fields to the qubit.

This is how we can 'program' the state of the qubit!

Using Euler's formula to 'program a qubit

Outline:

- Infinite sums

- Euler's formula

- Infinite products

Definition of the Euler number:

Example:

\(x = 2, N = 100 \)

To think that you multiply the number \(1.02\) with itself \(100\) times and you will get an approximation of \(e^2 \approx 7.39\) - that's what people admire about Euler's formulas!

Infinite products

Definition of the Euler number:

We saw that EM drive creates qubit oscillation:

What if we would remove the imaginary number \(i\)?

It is very difficult to implement it on a quantum computer but if we would find a way then we could make a lot of money solving problems in industry.

The right-hand side is a polynomial and the protocol called quantum signal processing can be used to implement it on a quantum computer.

Ongoing research on quantum algorithms!

Definition of the Euler number:

We saw that EM drive creates qubit oscillation:

What if we would remove the imaginary number i?

The right-hand side is a polynomial and the protocol called quantum signal processing can be used to implement it on a quantum computer.

Ongoing research on quantum algorithms!

I'm not sure if Euler had ideas about quantum computations.

I am sure that if he was alive today then he would be working on quantum computing!

It is very difficult to implement it on a quantum computer but if we would find a way then we could make a lot of money solving problems in industry.

Double-bracket quantum algorithms for diagonalization

Marek Gluza

NTU Singapore

slides.com/marekgluza

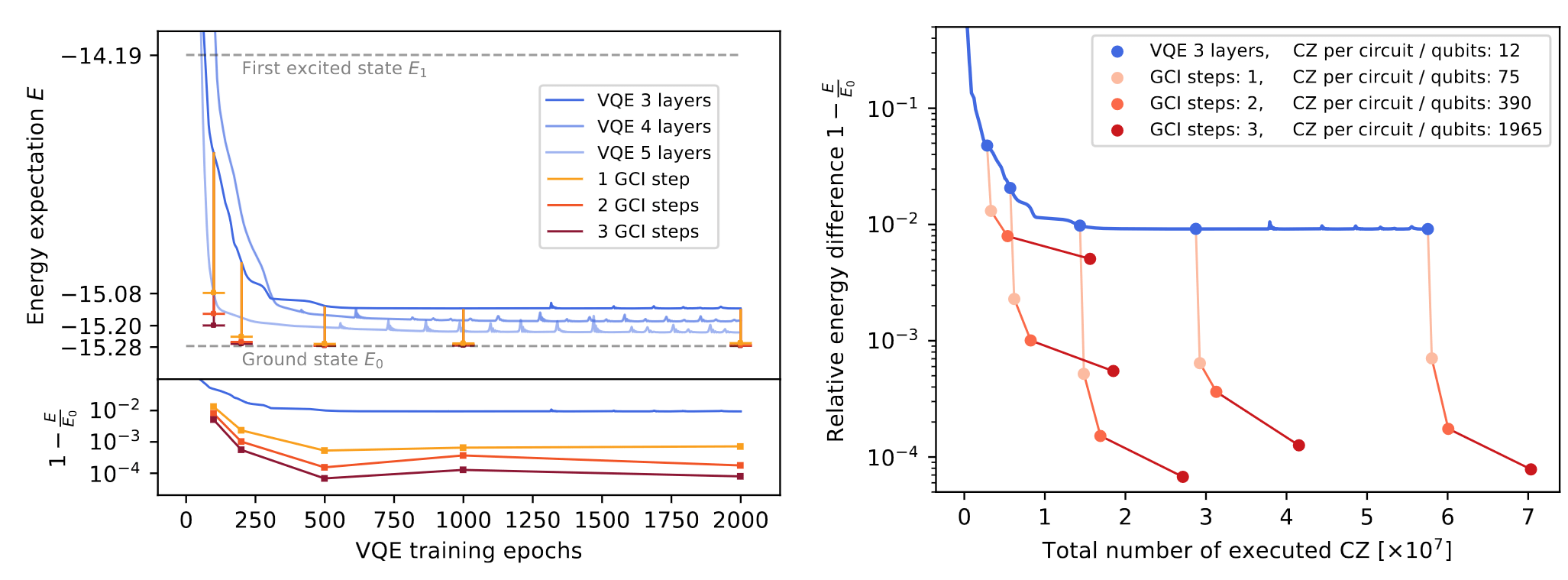

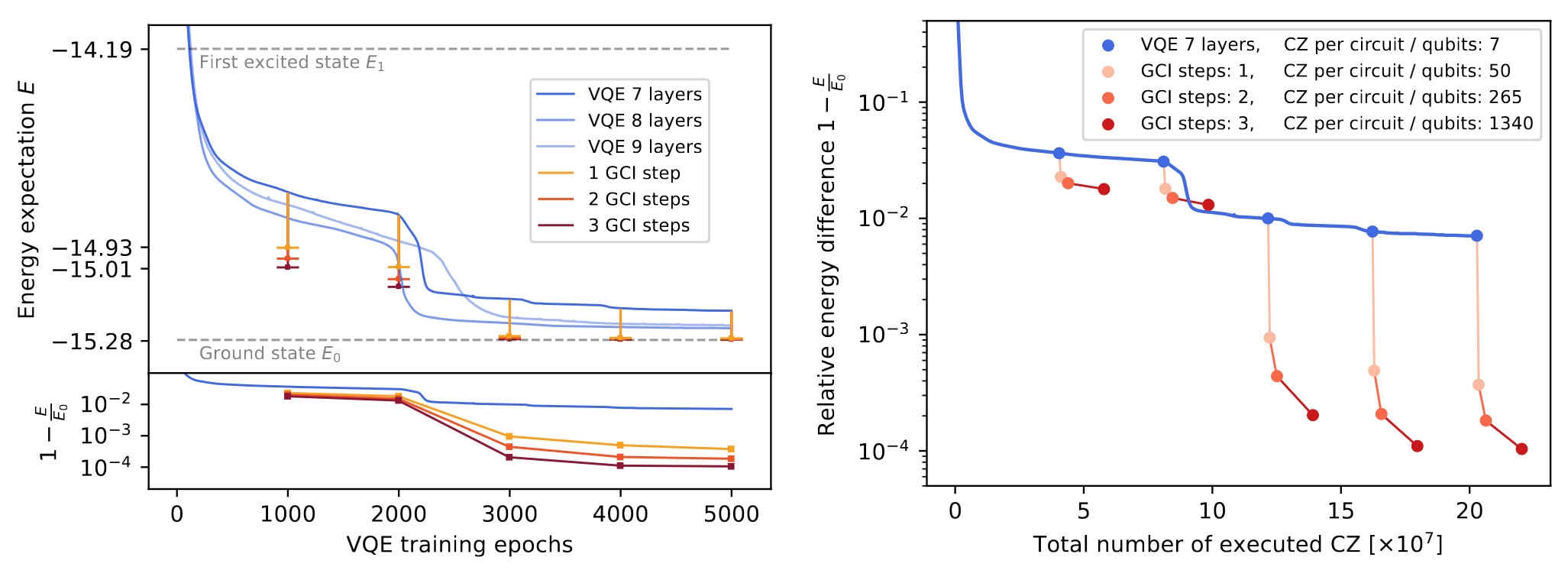

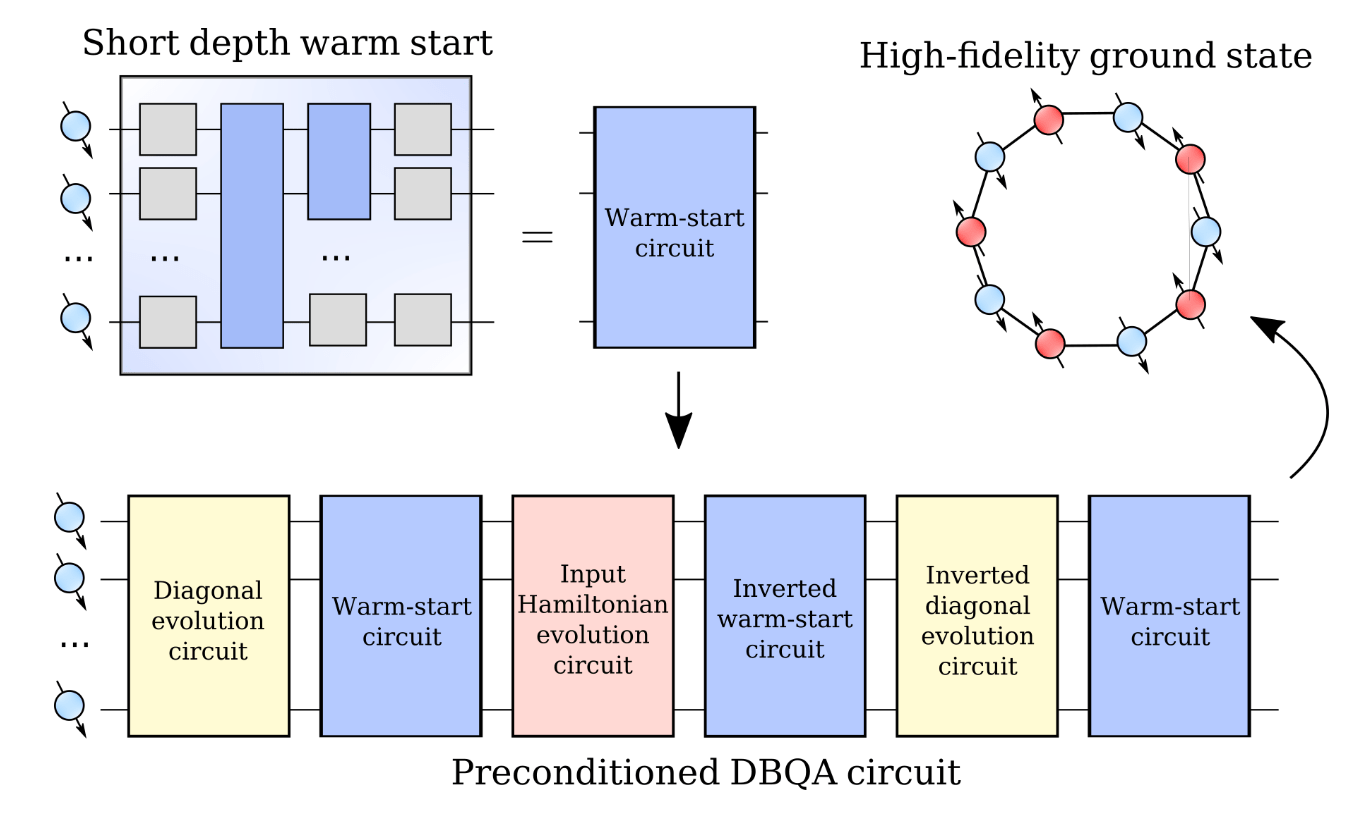

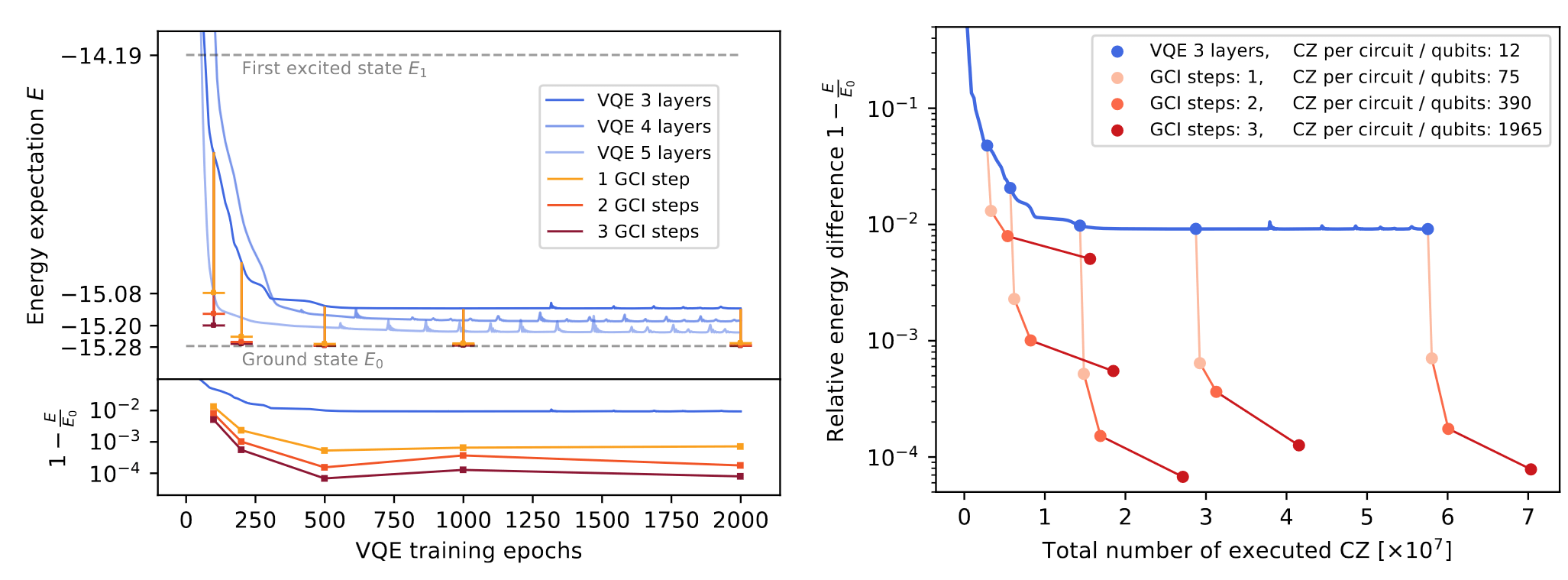

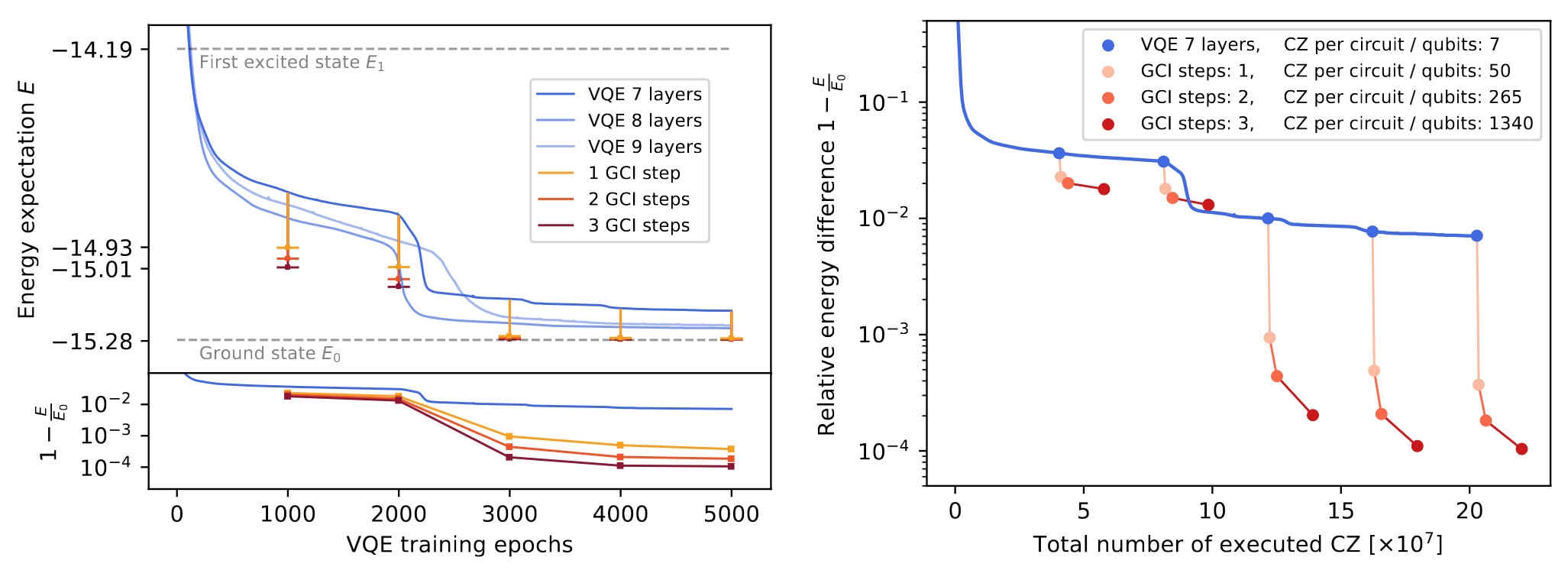

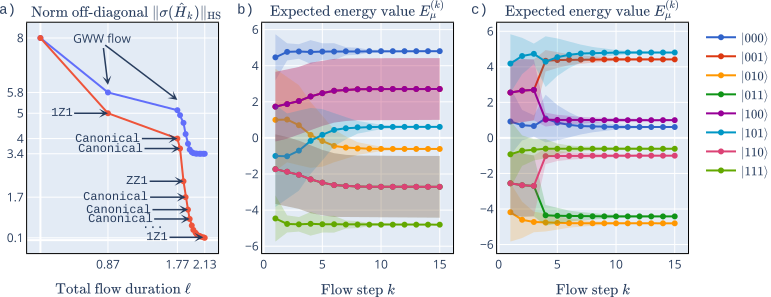

Gate count after VQE warm-start:

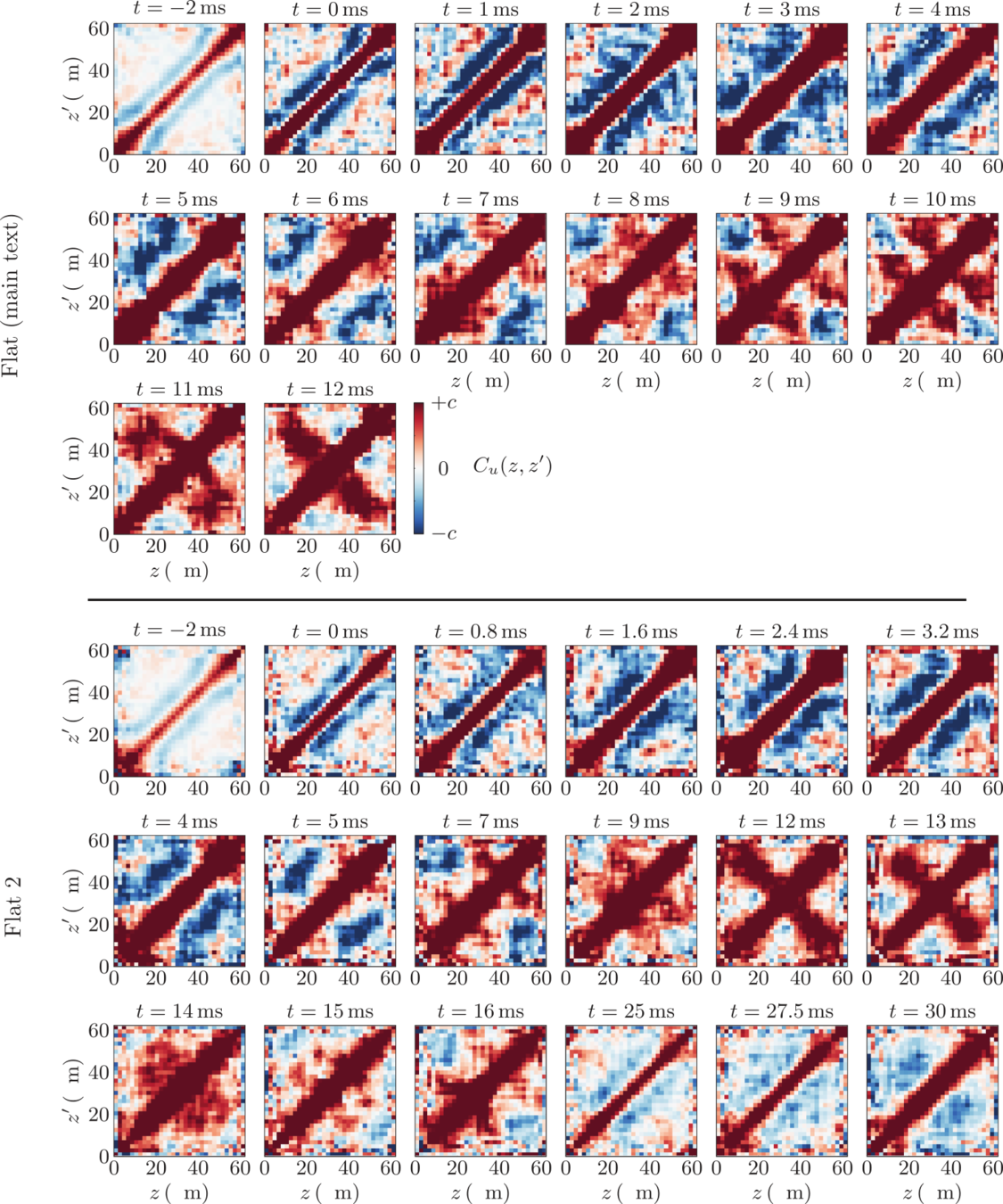

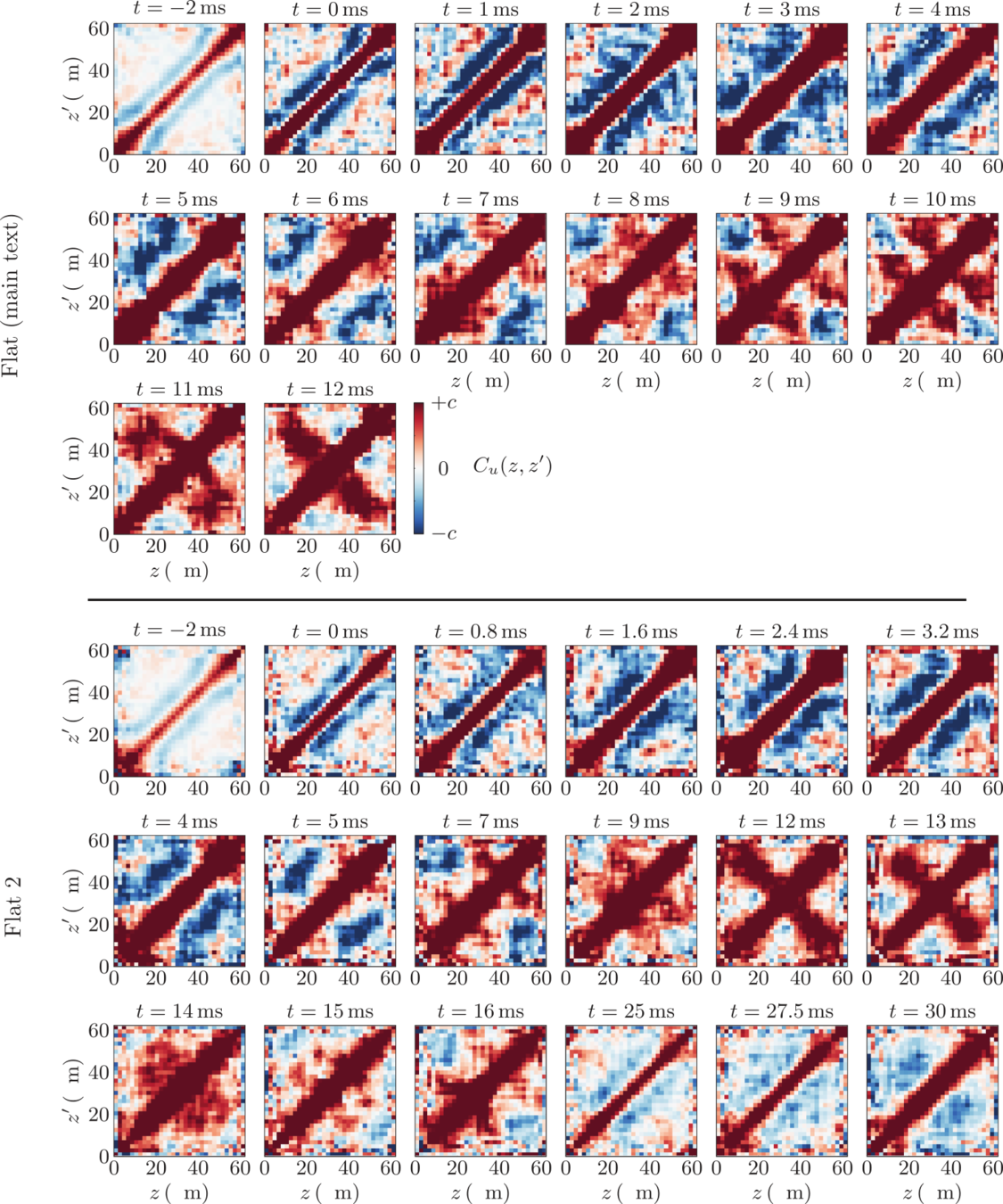

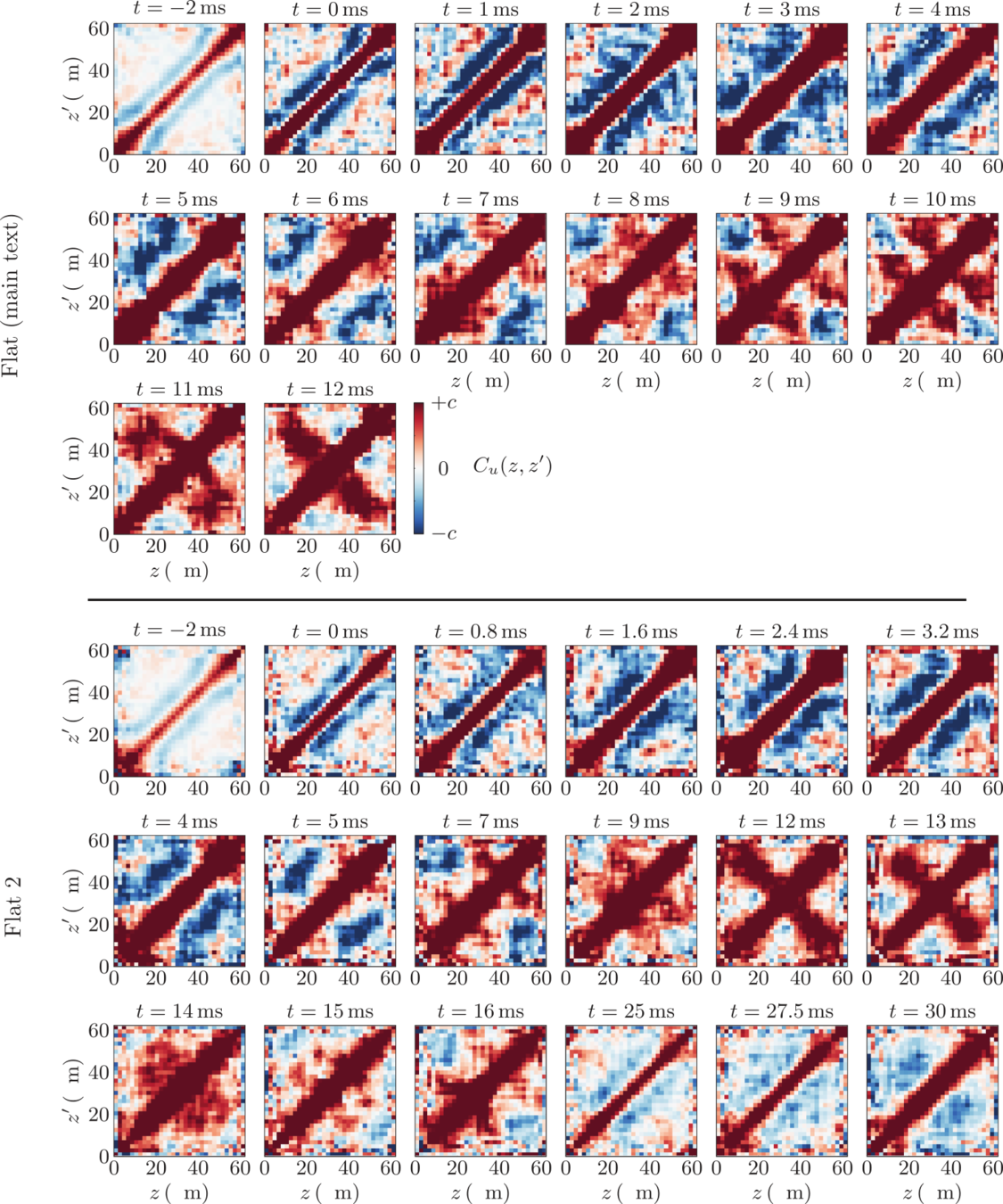

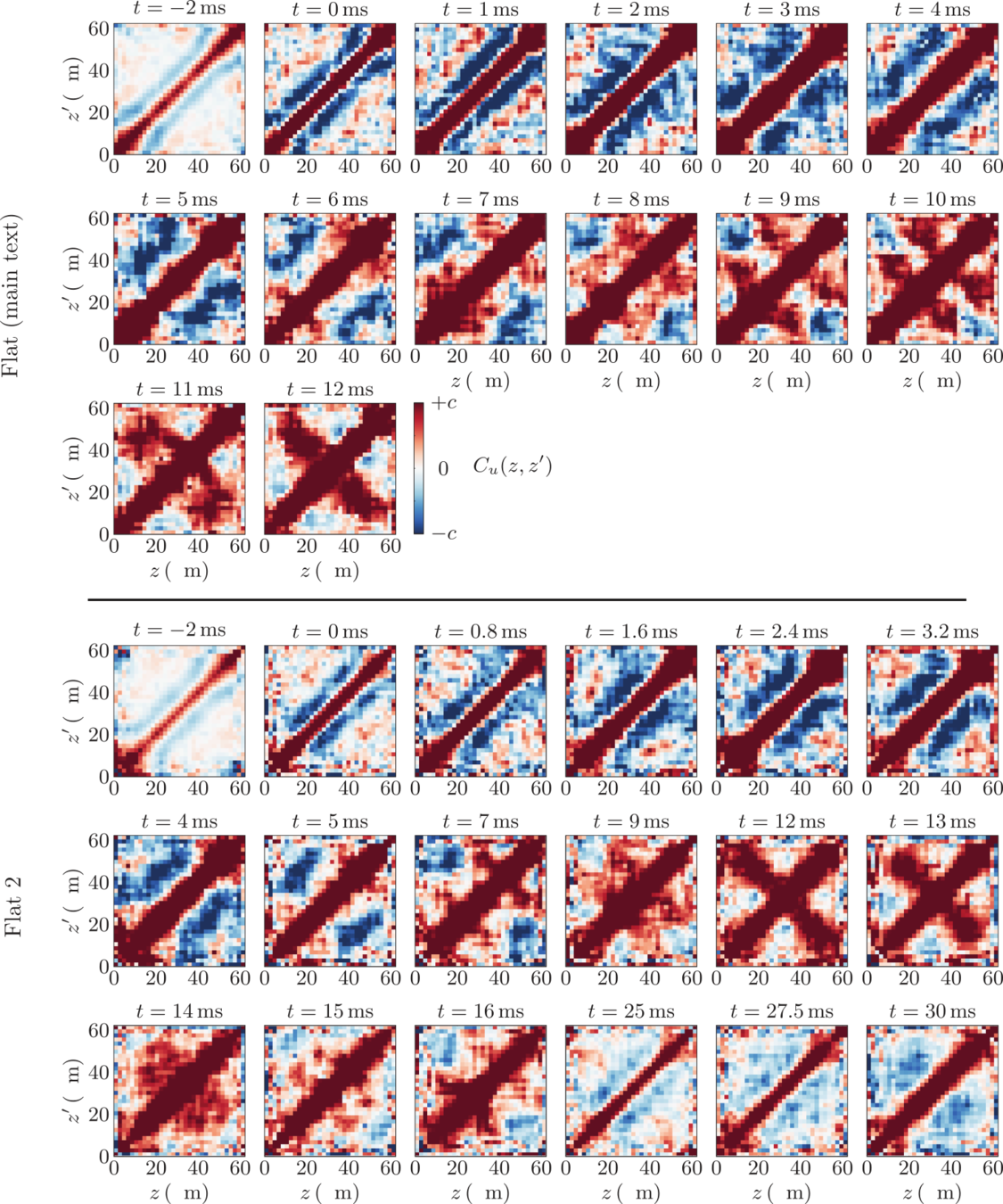

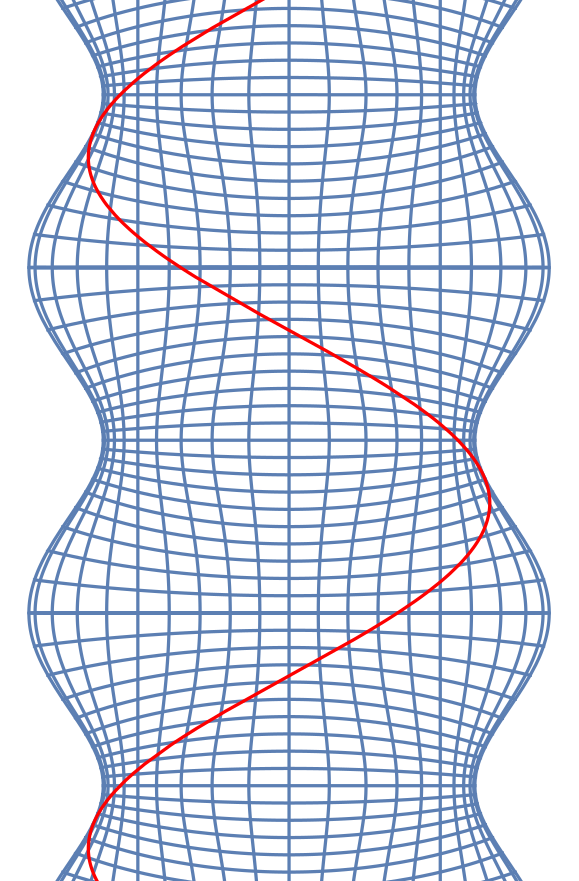

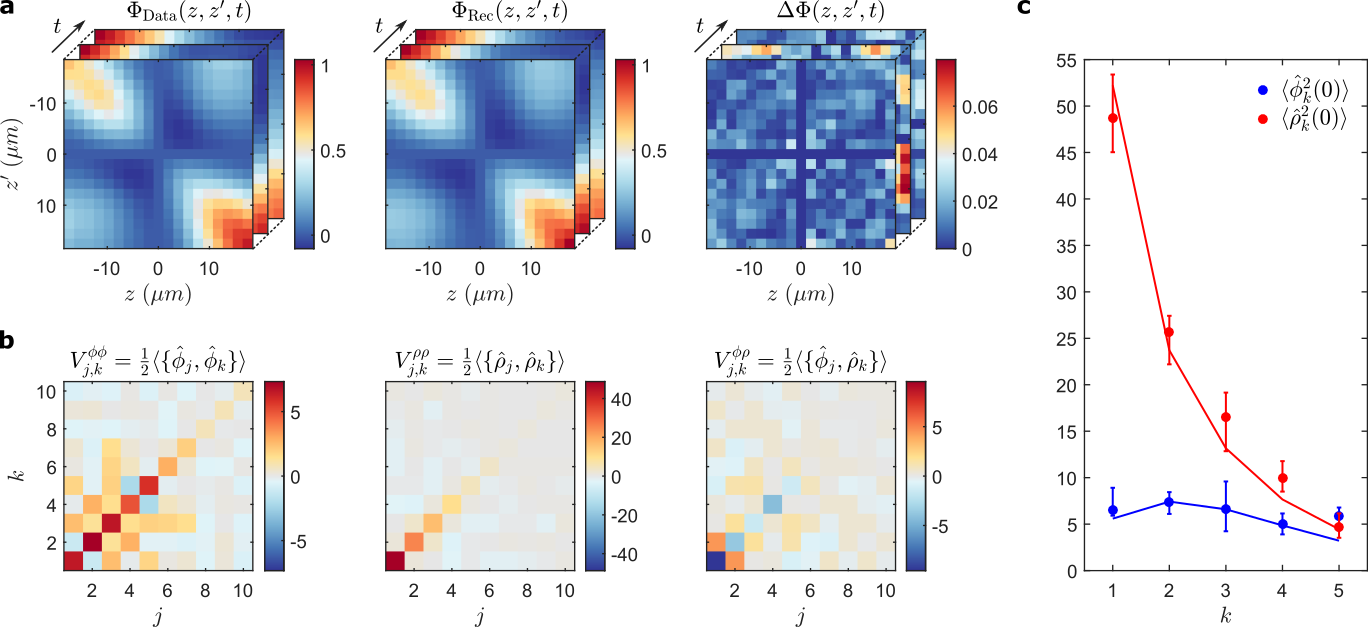

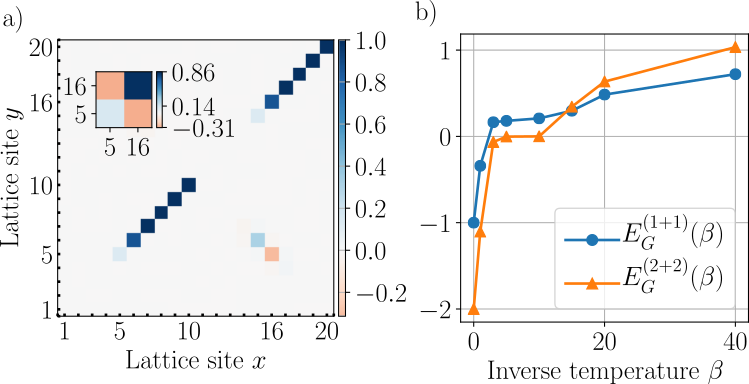

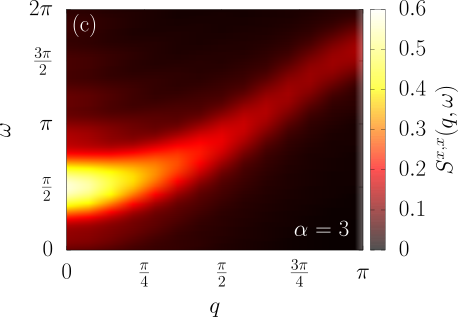

Experimental Observation of Curved Light-Cones in a Quantum Field Simulator

M. Tajik, J. Schmiedmayer

Breaking of Huygens-Fresnel principle in inhomogeneous Tomonaga-Luttinger liquids

Spyros Sotiriadis

Per Moosavi

Tomography for phonons

https://arxiv.org/abs/1807.04567

https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.09000

Quantum mechanics

used to be called matrix mechanics

We understood \(q\in \mathbb C\). What if \(q\) was a matrix?

Check: It makes because if \(A\in \mathbb C ^{n\times n} \) then \(A^k\in \mathbb C ^{n\times n} \) and we can add matrices of the same dimension.

Examples of infinite sums

Quantum mechanics

used to be called matrix mechanics

Quantum mechanics

used to be called matrix mechanics

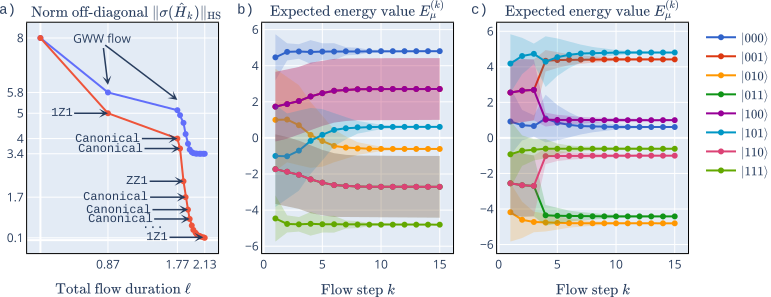

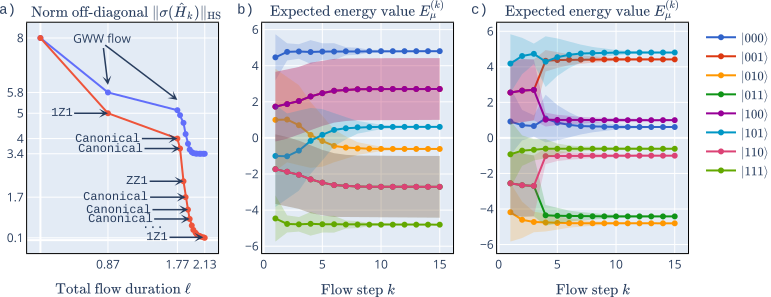

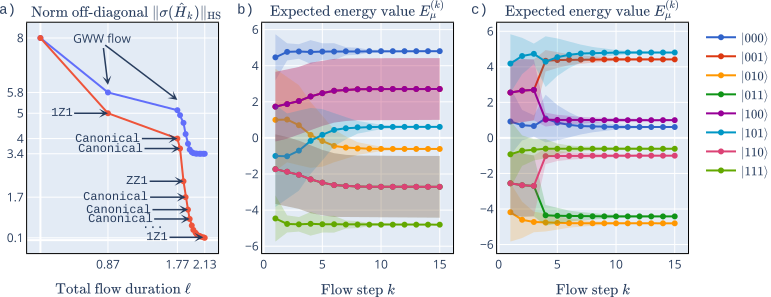

Why double a bracket?

Why double a bracket?

2 qubit unitary

Canonical

Double-bracket quantum algorithms

are inspired by double-bracket flows

and allow for quantum compiling of short-depth circuits which approximate grounds states

Inspired by double-bracket flows we compiled quantum circuits which yield quantum states relevant for material science

2 qubit unitary

Canonical

Double-bracket rotation ansatz

antihermitian

Rotation generator:

Input:

Unitary rotation:

Double-bracket rotation:

Double-bracket rotation ansatz

Rotation generator:

Input:

Unitary rotation:

Double-bracket rotation:

Key point: If \(\hat D_0\) is diagonal then

\(\hat H_1\) should be "more" diagonal than \(\hat H_0\)

Double-bracket rotation ansatz

Rotation generator:

Input:

Double-bracket rotation:

Restriction to off-diagonal

Lemma:

Proof: Taylor expand, shuffle around (fun!)

Double-bracket rotation ansatz

Rotation generator:

Input:

Double-bracket rotation:

Restriction to off-diagonal

Lemma:

Proof: Taylor expand, shuffle around (fun!)

A new approach to diagonalization on a quantum computer

Double-bracket iteration

Głazek-Wilson-Wegner flow

Restriction to off-diagonal

Restriction to diagonal

as a quantum algorithm

(addendo: where it's coming from)

Głazek-Wilson-Wegner flow

as a quantum algorithm

(addendo: where it's coming from)

New quantum algorithm for diagonalization

0

0

0

0

1) Dephasing

2) Group commutator

3) Frame shifting

Fun but painful because probably not possible efficiently

What about other methods?

0

0

0

0

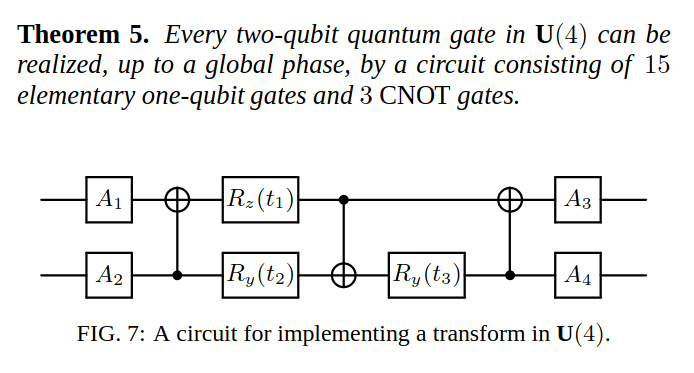

Universal gate set:

single qubit rotations + generic 2 qubit gate

Universal gate set can approximate any unitary

What is a universal quantum computer?

quantum compiling approximates unitaries with circuits

Quantum compiling

2x2 unitary matrix - use Euler angles

4x4 unitary matrix - use KAK decomposition + 3x CNOT formula

2 qubit unitary

Canonical

KAK decomposition, Brockett's work etc

=

2 qubit unitaries modulo single qubit unitaries are a 3 dimensional torus

Quantum compiling

\(2\) qubits - \(4\times 4\) unitary matrix - use KAK decomposition + \(3\) CNOT formula

Quantum compiling

\(1\) qubit - \(2\times 2\) unitary matrix - use Euler angles

\(n\) qubits - \(2^n\) unitary matrix - use quantum Shannon decomposition + \(O(4^n)\) CNOT formula

Variational quantum eigensolver

0

0

0

0

+

+

+

+

+

This works but is inefficient

This is efficient but doesn't work

Open: fill this gap!

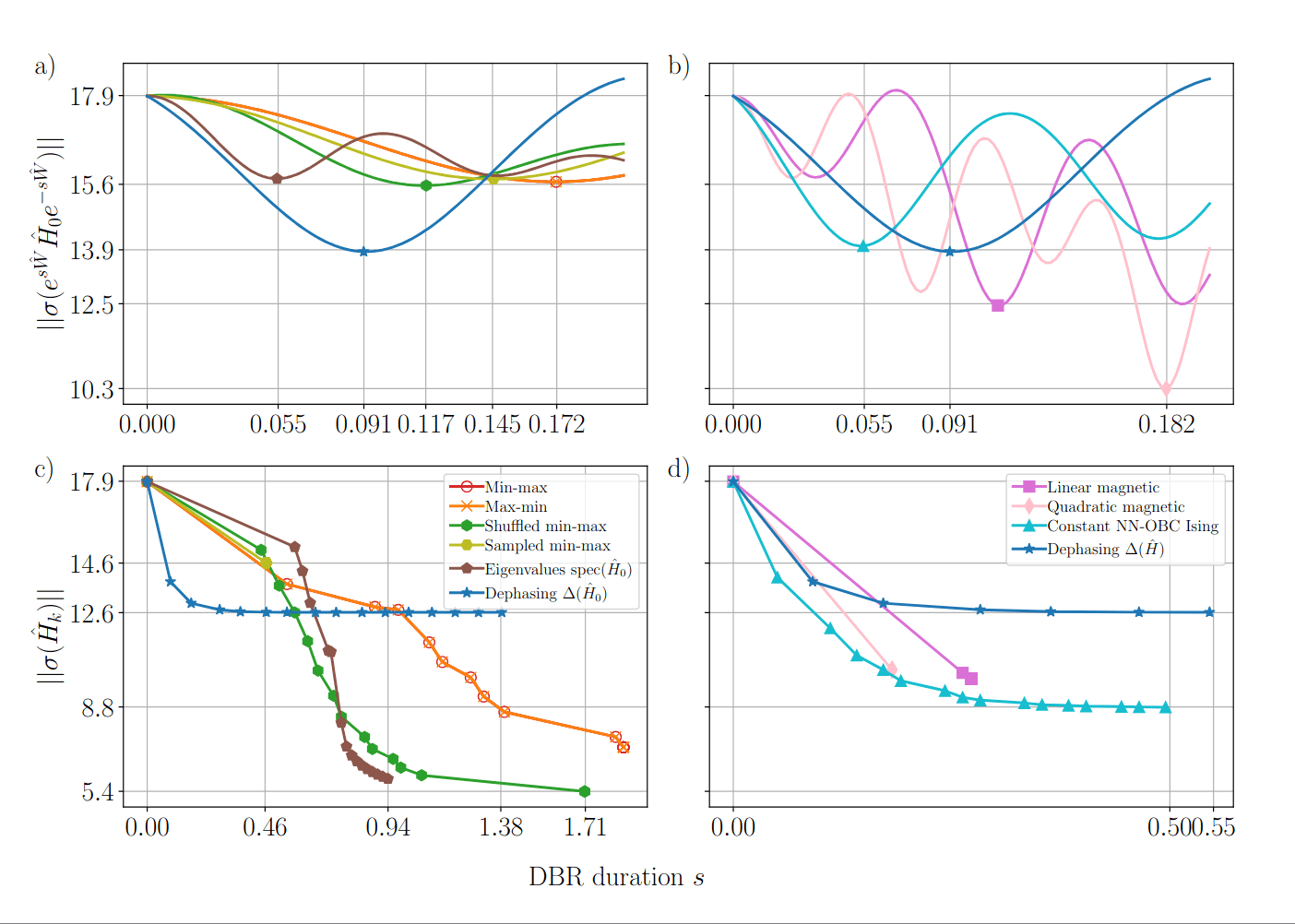

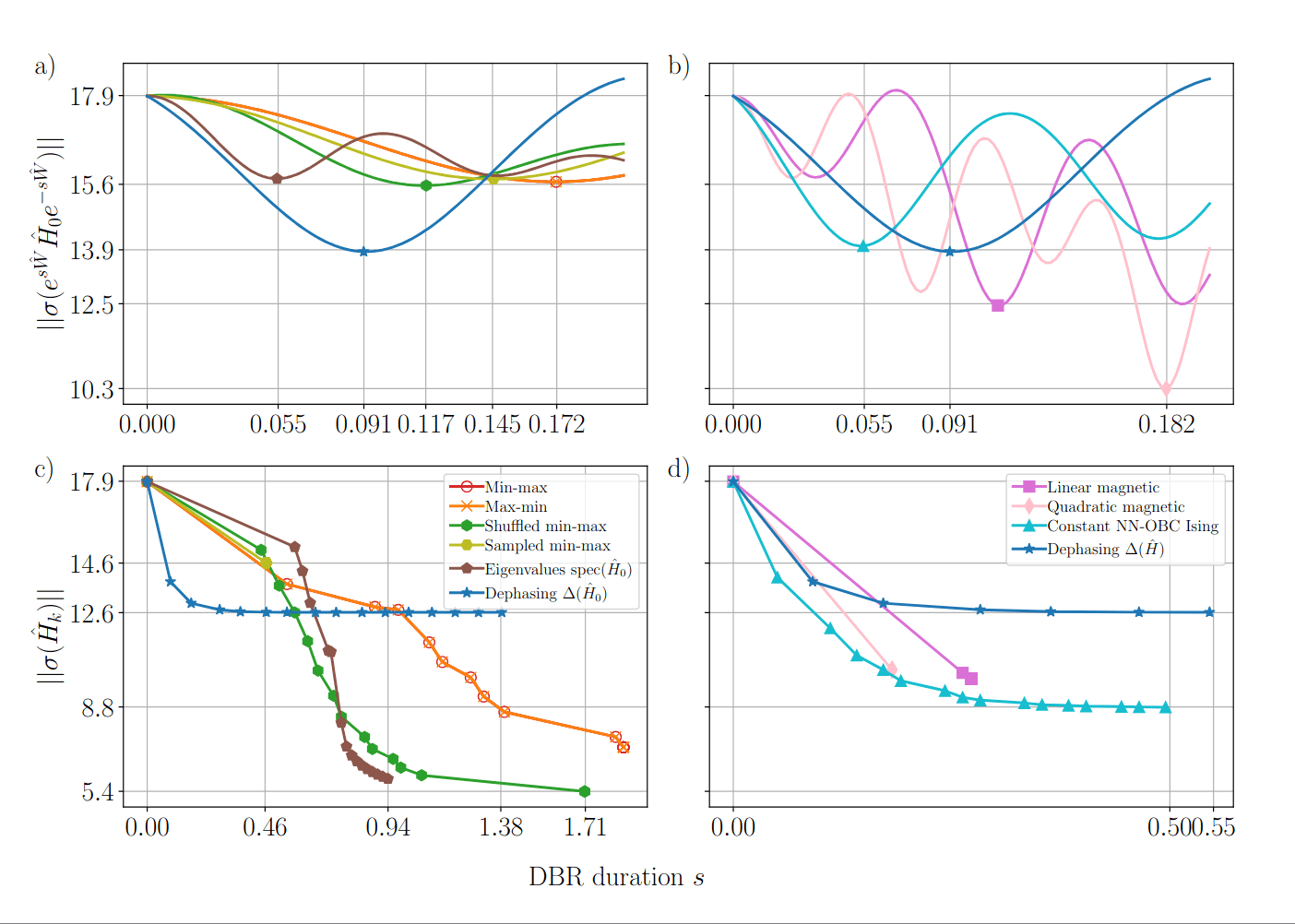

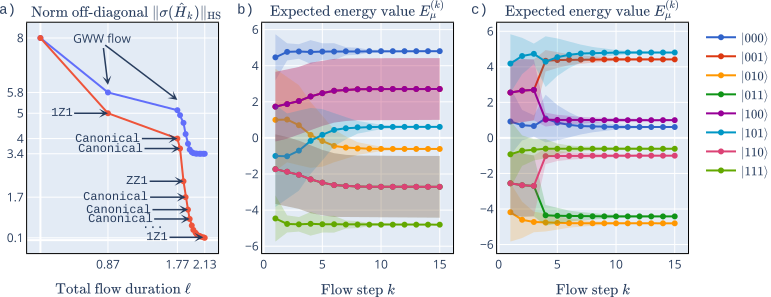

Double-bracket iteration

Rotation durations:

Input:

Diagonal generators:

A new approach to diagonalization on a quantum computer

Great: we can diagonalize

How to quantum compile?

How to quantum?

Group commutator

0

0

0

0

Want

New bound

Group commutator during iteration

0

0

0

0

Group commutator during iteration

0

0

0

0

Double-bracket iteration

Rotation durations:

Input:

Diagonal generators:

A new approach to diagonalization on a quantum computer

Great: we can diagonalize

How to quantum compile?

Replace by the group commutator

Group commutator iteration

Double-bracket iteration

Double-bracket iteration

Transition from theory to QPUs

How well does it work?

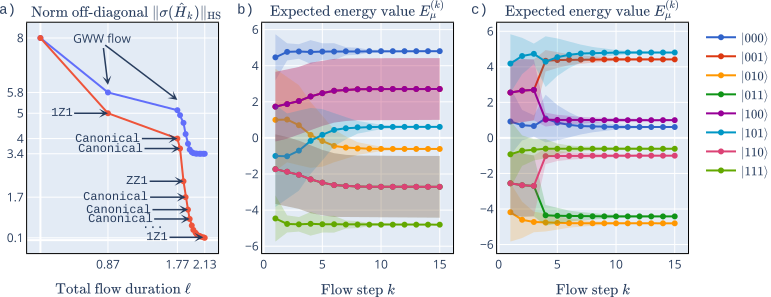

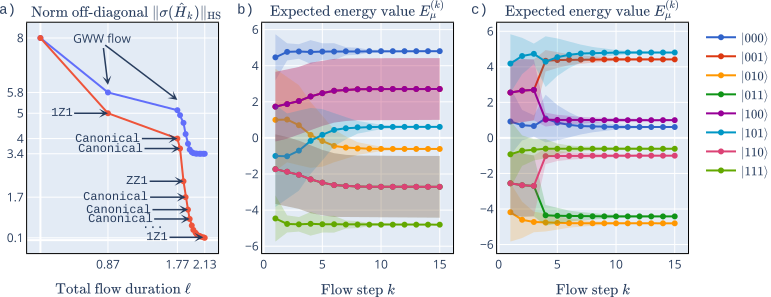

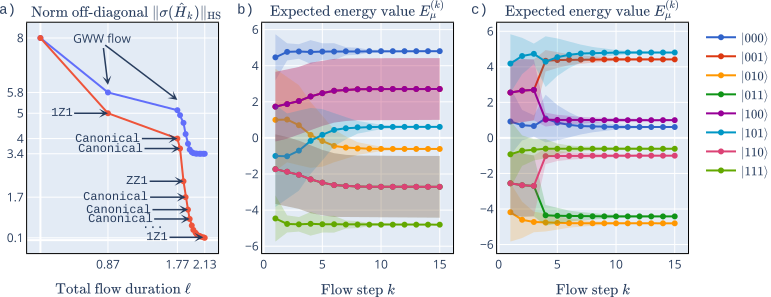

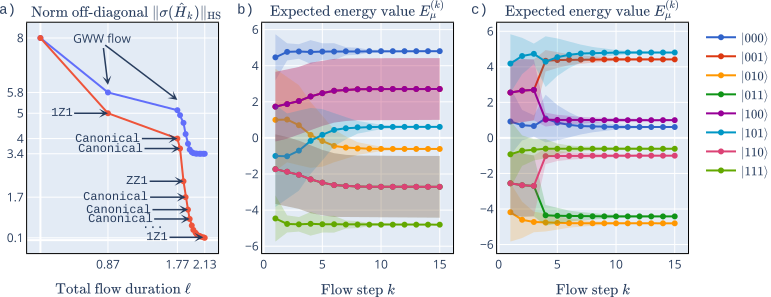

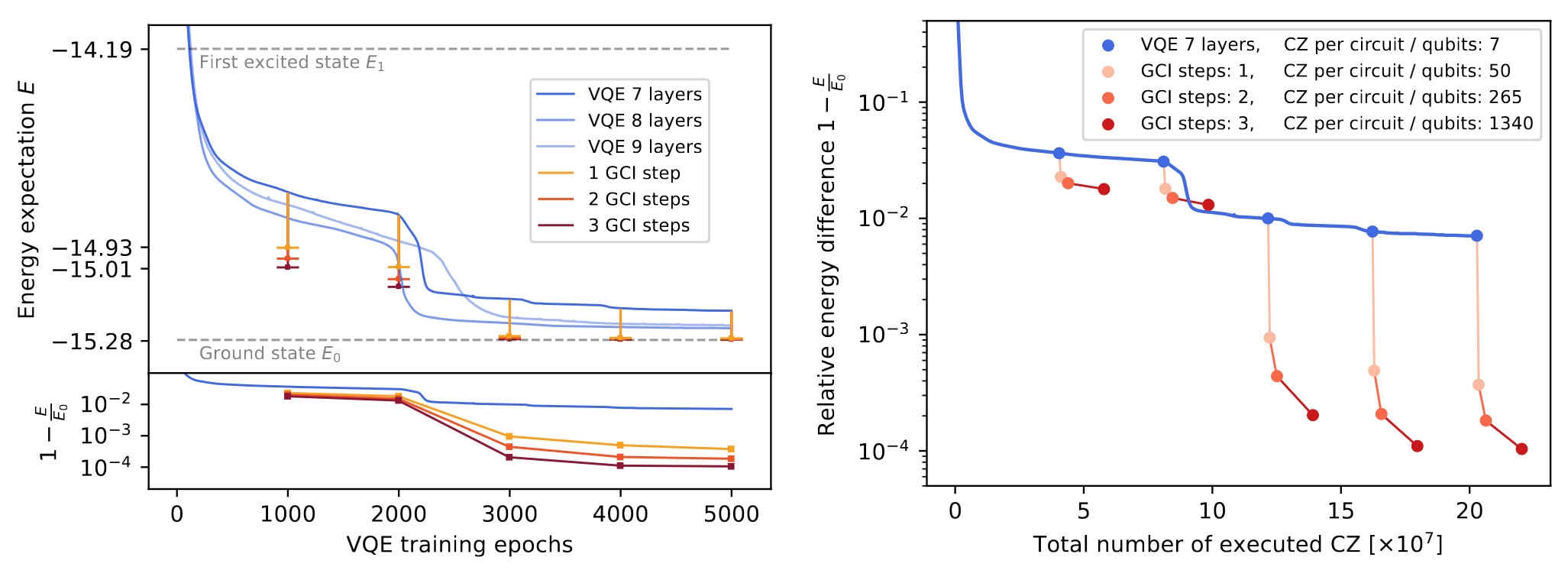

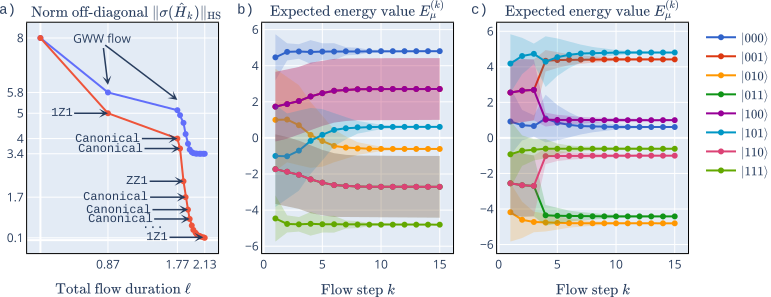

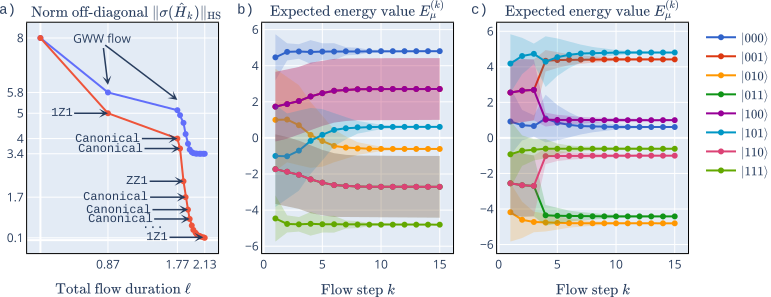

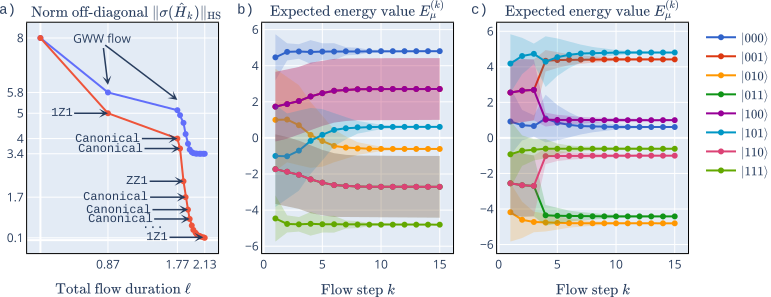

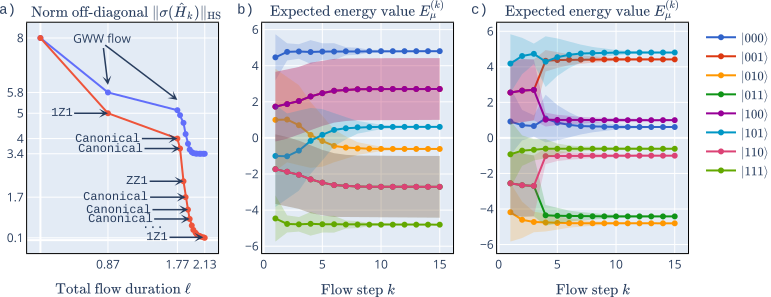

Variational flow example

Notice the steady increase of diagonal dominance.

Variational vs. GWW flow

Notice that degeneracies limit GWW diagonalization but variational brackets can lift them.

GWW for 9 qubits

Notice the spectrum is almost converged.

GWW for 9 qubits

Notice that some of them are essentially eigenstates!

How does it work after warm-start?

10 qubit, 50 layers of CNOT - 99.5% ground state fidelity

This both works and is efficient

How to interface VQE and DBQA?

Quantum Dynamic Programming

with J. Son, R. Takagi and N. Ng

QDP code structure

Warm-start unitary from variational quantum eigensolver

0

0

0

0

+

+

+

+

+

DBQA input with warmstart

Use unitarity and get circuit VQE insertions

10 qubit, 50 layers of CNOT - 99.5% ground state fidelity

2 qubit unitary

Canonical

Canonical

For quantum compiling we use:

- higher-order group commutators

- higher-order Trotter-Suzuki decomposition

- 3-CNOT formulas

New quantum algorithm for diagonalization

no qubit overheads

no controlled-unitaries

0

0

0

0

C

0

0

0

0

Simple

=

Easy

Doesn't spark joy :(

Double-bracket quantum algorithm for diagonalization

new approach to preparing useful states

0

0

0

0

What else is there?

Linear programming

Matching optimization

Diagonalization

Sorting

QR decomposition

Toda flow

Double-bracket flow

Runtime-boosting heuristics

Analytical convergence analysis

Group commutator bound

Hasting's conjecture

Relation to other quantum algorithms

Code is available on Github

0

0

0

0

C

Double-bracket quantum algorithms for diagonalization

with J. Son, R. Takagi and N. Ng

Quantum dynamic programming

Material science?

0

0

0

0

C

How to dynamically quantum?

Group commutator

0

0

0

0

Want

New bound

Group commutator

0

0

0

0

Want

How to get ?

Phase flip unitaries

N

S

N

S

N

S

N

S

N

S

N

S

N

S

Phase flip unitaries

Evolution under dephased generators

0

0

0

0

We can make it efficient:

Use unitarity

and repeat many times

New quantum algorithm for diagonalization

0

0

0

0

1) Dephasing

2) Group commutator

3) Frame shifting