Introducción al Cálculo

2. Límites

1. Funciones

Continuidad

El Caso 0/0

Polinomios

Racionales

Límites que tienden a infinito

Método Gráfico

Ejemplos

Teorema del Valor Intermedio

Método Numérico

3. Derivada

Recta Tangente

Definición por Límites

Teorema de los Extremos

Para navegar, utiliza las flechas del teclado

4. Integral

Ejemplos

Funciones

Repaso

Limits

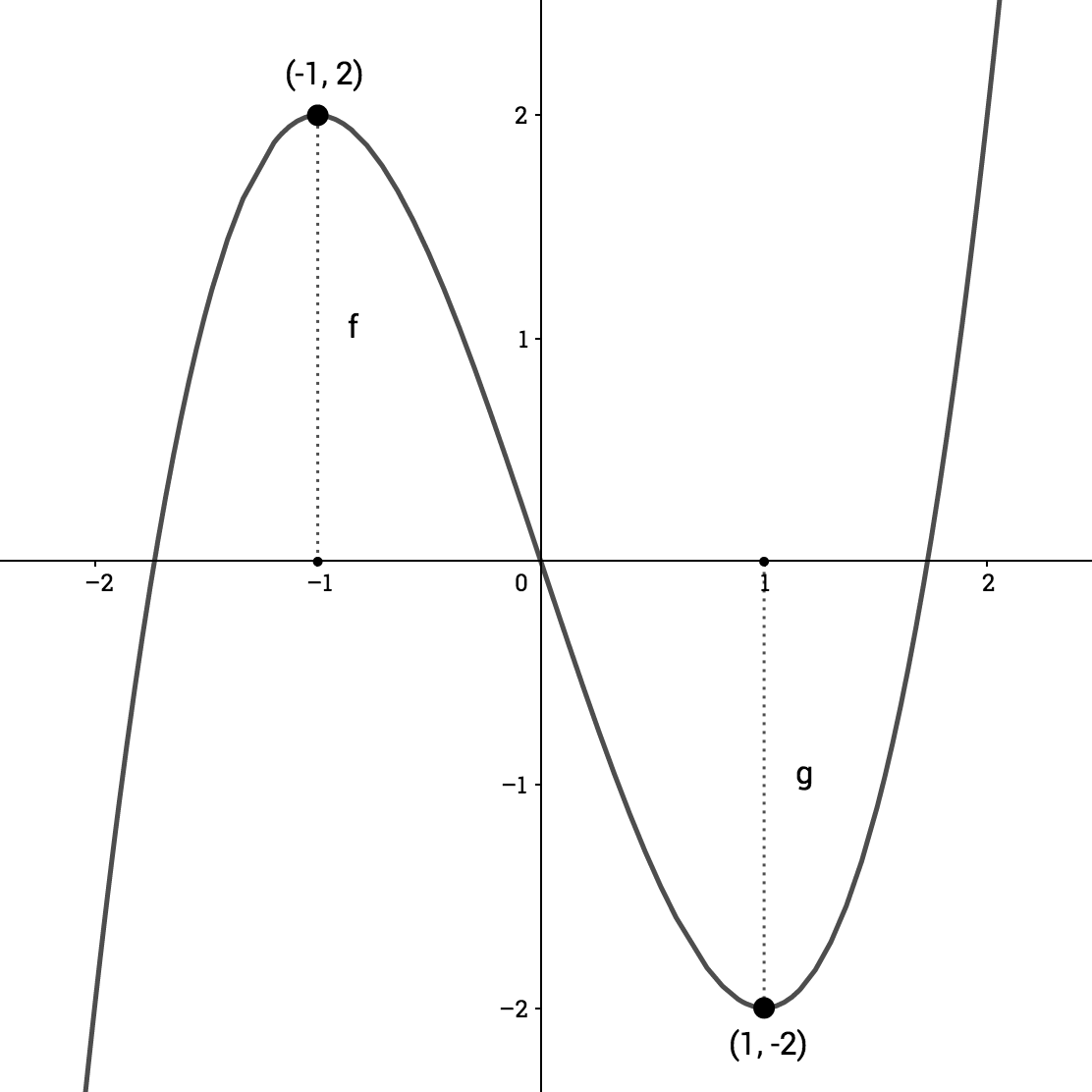

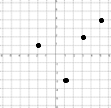

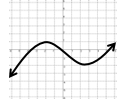

\(f(x) = x^3-3x \)

\(f(x) = x^3-3x \)

$$ \sqrt{3} $$

$$ -\sqrt{3} $$

Polinomios

Continuo en \((-\infty, \infty)\)

\(y\uparrow\infty\) conforme \(x\rightarrow \infty\)

\(y\downarrow-\infty\) as \(x\rightarrow -\infty\)

Los extremos van en direcciones opuestas, así que el grado del término principal debe ser impar (odd.)

\(y\) crece conforme \(x\rightarrow\infty\), así que el coeficiente líder debe ser positivo

En este caso

¿Y qué si quisiéramos encontrar los valores máximos o mínimos de \(p(x)\)?

Usando distintas técnicas de diferenciación se puede, y lo haremos con frecuencia conforme avancemos nuestro estudio en Cálculo.

$$ = x(x^2 -3) $$

$$x = 0$$ $$ x=\sqrt{3} $$ $$ \ x=-\sqrt{3}$$

$$ \text{Sabemos que } p(x) = x \ (x+\sqrt{3})(x-\sqrt{3})$$

$$ p(x) = x^3 -3x $$

\( \text{Encuentra la fórmula de un polinomio cuyas soluciones sean } x=0, x = \sqrt{3} \ y \ x= -\sqrt{3}\)

\(\Leftarrow \) esta es la forma completamente factorizada de \(p(x)\)

\(\Leftarrow \) Este es tu polinomio completamente expandido a partir de las soluciones.

$$ \Rightarrow \text{Estas son soluciones ya que } p(0) = 0 ,\ \ p(\sqrt{3})=0 \ \text{ o } \ \ p(-\sqrt{3}) = 0. $$ Esto también implica que \(p(x)\) cruza el \(eje- x\) exactamente en estos puntos.

\(\Leftarrow \) multiplica los factores para llegar a esta forma

$$ p(x) = x^3 -3x $$

$$ p'(x) = 3x^2 -3 $$

$$ \Rightarrow p(x) \text{ tiene un máx. o un mín en } x=\pm 1$$

\(\text{ (saca la derivada) } \)

\(\text{ (iguálalo a 0) } \)

saltar

$$ 3x^2 -3=0$$

$$ 3x^2 =3$$

$$ x =\pm 1$$

\(\text{ (la derivada es solo la pendiente, por lo que si } f'(x) = 0 \text{, entonces este punto debe ser un mínimo o máximo} \)

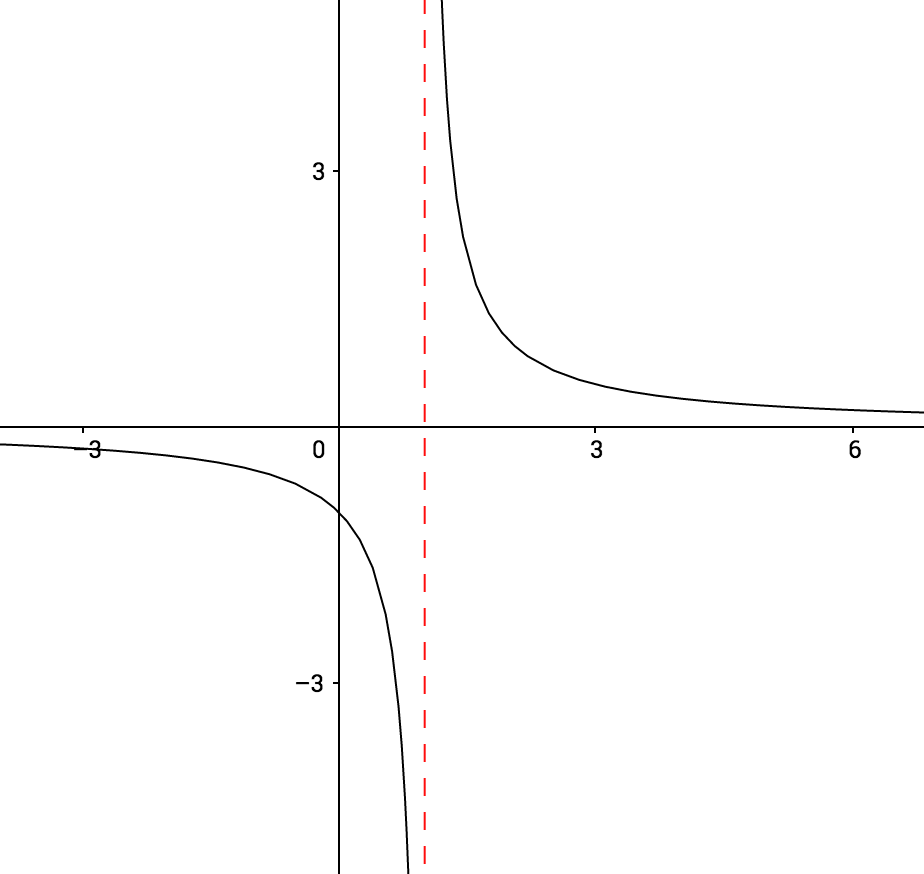

Funciones Racionales

$$f(x) = \dfrac{1}{x-1} $$

$$\text{ asíntota vertical} : $$

$$x=1$$

$$\text{asíntota horizontal } : $$

$$y=0$$

$$y-\text{intercept } : $$

$$y=-1$$

$$x-\text{intercept } : $$

$$\text{none }$$

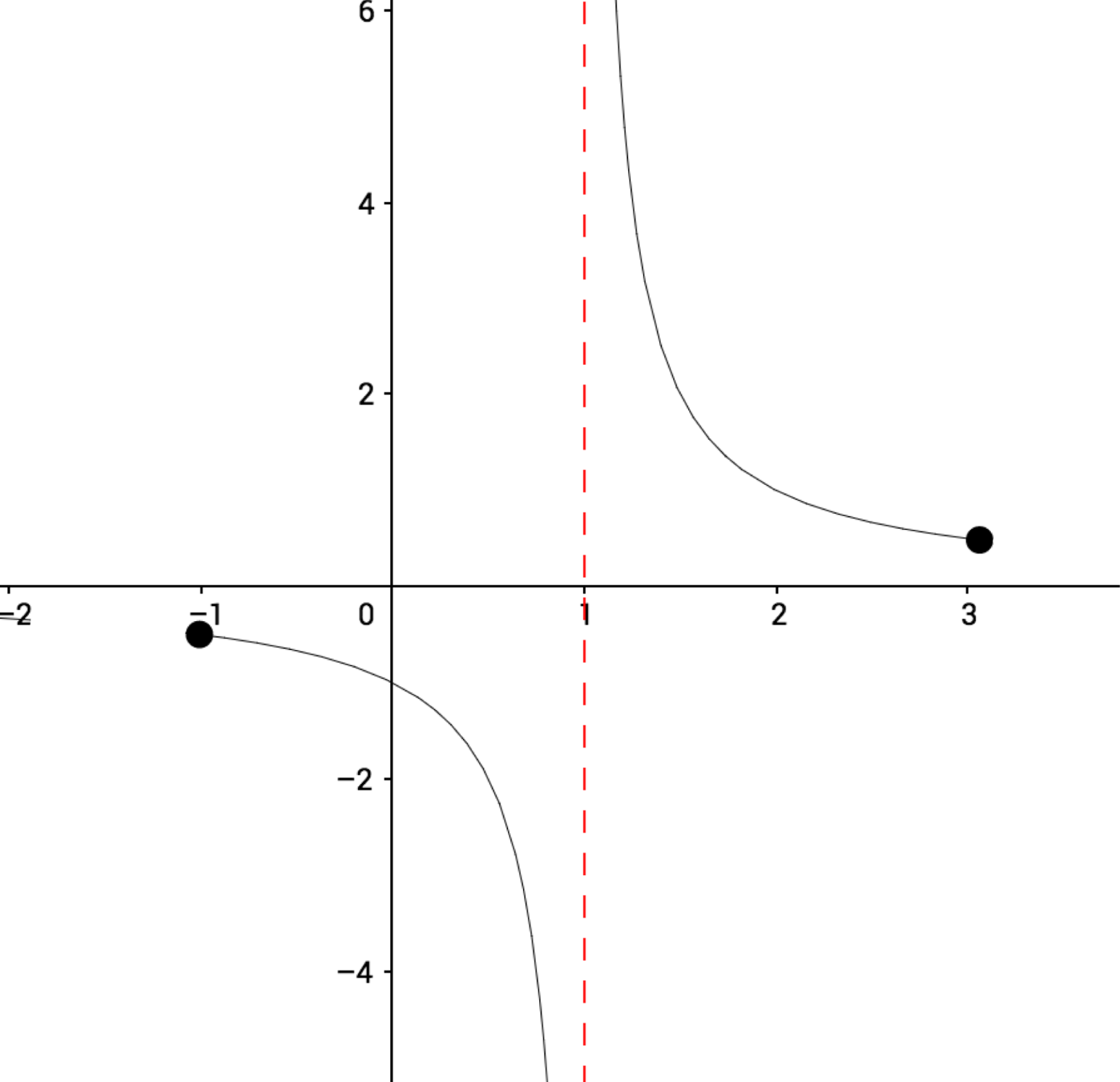

Rational Functions

$$f(x) = \dfrac{1}{x-1} $$

$$ \text{set notation: } \ x\in [-1,3]$$

$$ -\{1\} $$

$$ \text{interval notation: } [-1,1) \cup (1, 3] $$

$$\text{domain of } f(x): $$

Continuidad

y conceptos fundamentales para límites

Competencia a desarrollar: Identifica y aplica la continuidad de una función

Objetivos

- Conocer los conceptos de límite de una función en un punto (tanto finito como infinito) y de límite en el ±.

- Saber calcular límites de cocientes de polinomios.

- Saber determinar las asíntotas verticales, horizontales y oblicuas de una función.

- Conocer el concepto de límite lateral y su relación con el de límite.

- Conocer las propiedades algebraicas del cálculo de límites, los tipos principales de indeterminación que pueden darse y las técnicas para resolverlas.

- Conocer el concepto de continuidad de una función en un punto, incluida la continuidad lateral, y, como consecuencias elementales, la conservación del signo y la acotación de la función en un entorno del punto.

- Saber dónde son continuas las funciones elementales.

- Conocer los distintos comportamientos de discontinuidad que pueden aparecer y saber reconocerlos usando los límites laterales.

- Saber determinar la continuidad de las funciones definidas a trozos.

- Conocer el concepto de continuidad de una función en un intervalo y qué significa eso en los extremos del intervalo.

Repaso de dominios

¿cuál es el dominio para cada una de las siguientes funciones?

$$\lim_{x\rightarrow a}f(x) = L $$

$$ \lim_{x\rightarrow a^{+}} = L =\lim_{x\rightarrow a^{-}} $$

$$ \lim_{x\to a^{+}} f(x) = L $$

$$ \lim_{x\to a^{-}} f(x) = L $$

i.e.

entonces decimos "El límite de \(f(x)\) conforme \(x\) tiende a \(a\) es igual a \(L\)", y se escribe:

Existencia de un Límite

Si

y

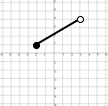

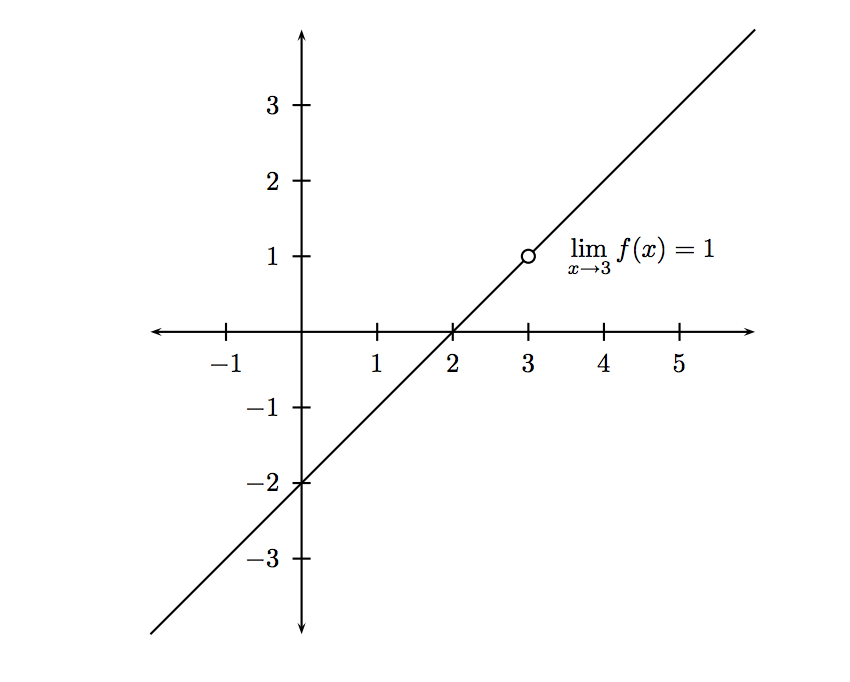

\(\text{ ¿A dónde se aproxima } f(x) \text{ conforme } x \rightarrow 2 ? \)

Este método intuitivo es clave para poder asimilar el concepto de límites más complejos. Pregúntate, ¿a dónde se acerca? ¿Se acercan ambos lados al mismo lugar? ¿Es continua?

\[\lim_{x\to2} f(x)= 4 \]

\[\text{Observa cómo} f(x) \text{ es continua en } x=2 \]

Evaluando Límites:

Método Gráfico.

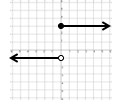

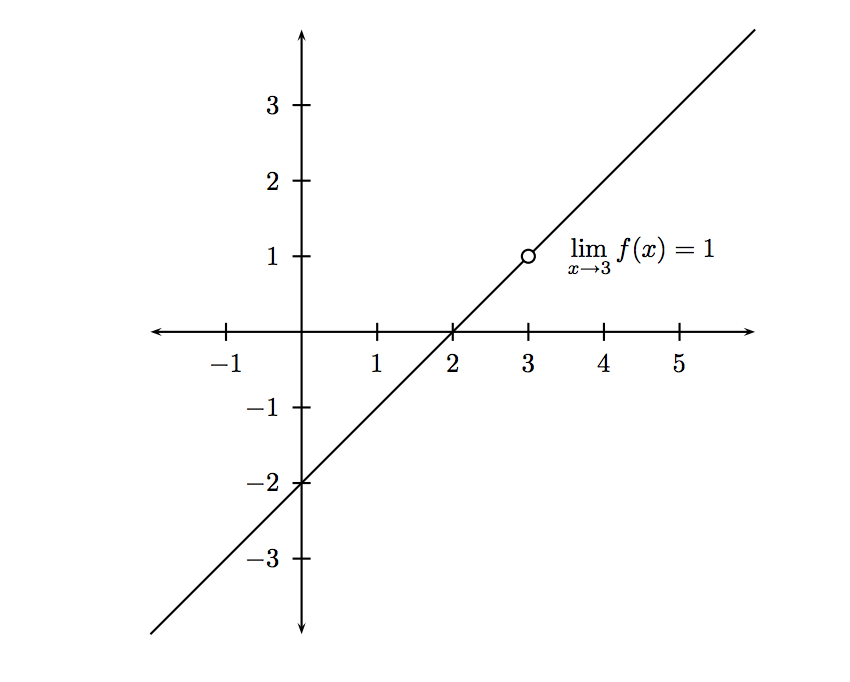

La ecuación de la función \(f\) es

\(f(x)=x-2\)

aunque debemos hacer explícito que esta es discontinua cuando \(x=3\)

\(f(x)=x-2 \ , x\ne 3\)

¿Cuál es el dominio de la función \(f?\)

cualquier valor de \(x\) excepto \(x=3\), ya que, como se observa, cuando \(x\) es 3, hay un agujero en la curva (que en este caso es una recta), lo cual indica que no hay una definición en \(x=3\).

\(\text{Sabemos que} \) \(f(3) \text{ es } \text{ indefinida} \)

\(\text{Pero ¿a dónde se aproxima} \) \(f(x) \text{ entre más se acerca } x \text{ a } 3? \)

\(f(3) = \text{ indefinido}\)

$$ \lim _{x\to3} f(x) = 1$$

$$ f(x) = x-2, x\ne3 $$

Es importante que tomes en cuenta que el concepto del límite

¡es el más importante en el estudio del Cálculo, tanto diferencial como integral!

Límites

Evaluando Límites - Método Gráfico

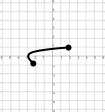

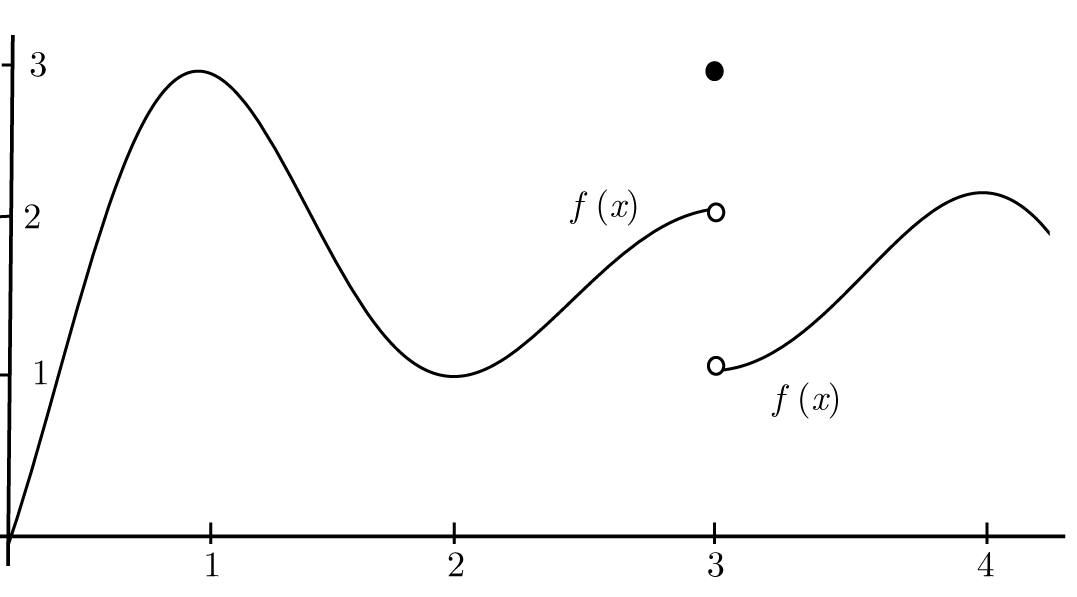

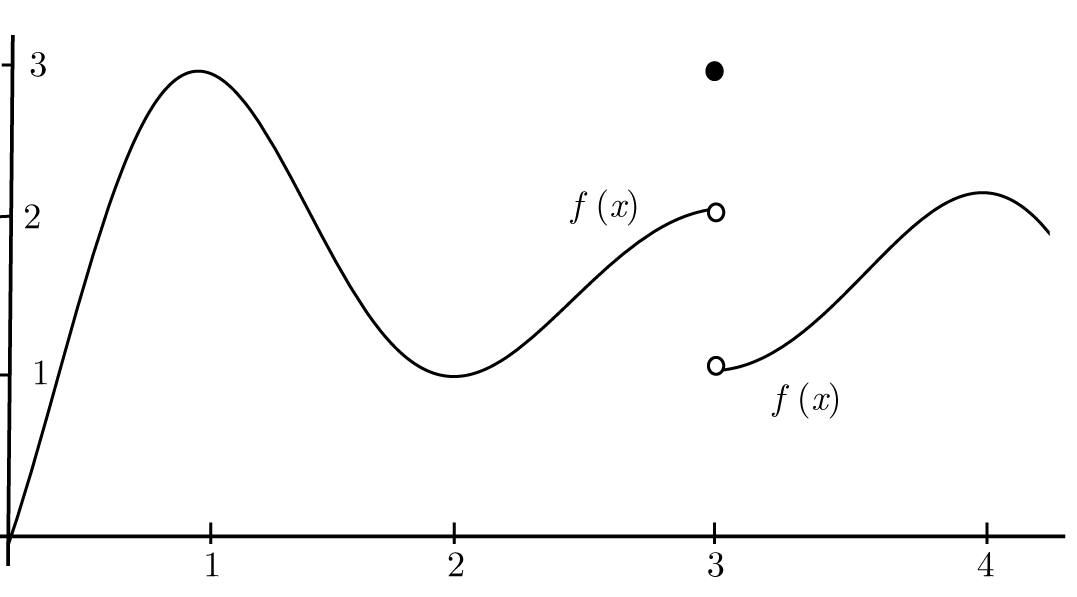

$$\lim_{x\to3^{-}} = $$

$$\lim_{x\to3^{+}} = $$

$$\lim_{x\to3} = $$

$$f(3) = $$

$$\lim_{x\to2^{+}} = $$

$$\lim_{x\to2^{-}} = $$

$$\lim_{x\to2} = $$

$$f(2) = $$

$$ \text{máximo absoluto} = (1,3) $$

$$ \text{mínimo absoluto} = \text{undefined}$$

$$ \text{máximo local } = (4,2) $$

\(2\)

\(1\)

\(\text{No Existe}\)

\(3\)

\(1\)

\(1\)

\(1\)

\(\text{indefinido}\)

\((1,3)\)

\((4,2)\)

$$ \text{crece en el intervalo: } (-\infty,1)\cup(2,3)\cup(3,4) $$

$$ \text{decrece en: } (1, 2)\cup(4,\infty) $$

¡Inténtalo tú hasta que saques todas bien!

$$\lim_{x\to3^{-}} = $$

$$\lim_{x\to3^{+}} = $$

$$\lim_{x\to3} = $$

$$f(3) = $$

$$\lim_{x\to2^{+}} = $$

$$\lim_{x\to2^{-}} = $$

$$\lim_{x\to2} = $$

$$f(2) = $$

$$ \text{Intervalos en los que }f(x) \text{ crece} = $$

$$ \text{Intervalos en los que }f(x) \text{ decrece} = $$

$$ \text{máximo absoluto} = $$

$$ \text{máximo local} = $$

$$x$$

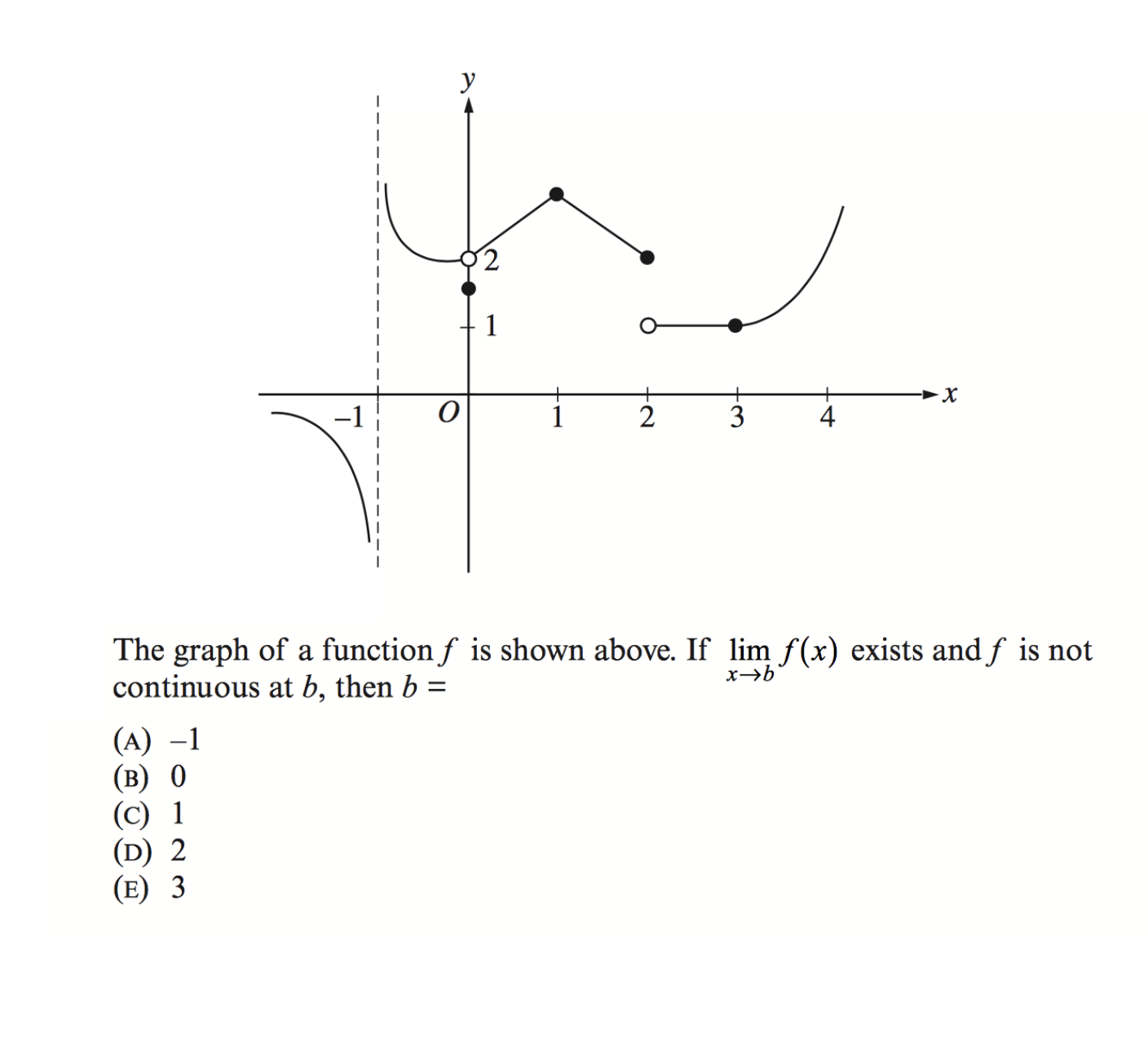

Definición de Continuidad

Un límite es aquel punto o recta (usualmente asíntota) donde una función convergería. Es decir, donde ambos lados de la gráfica de la función se encuentran. Puedes recordarlo haciéndote la siguiente pregunta:

¿A dónde se aproxima \( f(x) \) conforme \(x\) tiende a \( a\)?

Nos importa el valor de \(f(x)\) cuando \(x= a\), solo estamos interesados en los puntos infinitesimales que están justo antes y después del valor de

\(a\). El método de substitución para encontrar límites se puede utilizar cuando la función es continua en \(a\), es decir, que el límite de \(f(x)\) y el valor de \(f\) cuando \(x =a\) son iguales.

Es como evaluar una función para un valor de x, solo que puede darse el caso de que \(f\(x)\) no esté definida cuando \(x=a\). Es decir, puede ser que \(f(a)\) no exista, pero \( \lim_{x\to a} f(x) \) sí. Sin embargo, \(f(x)\) debe ser continua en el valor dado para poder utilizar el método de substitución. m En otras palabras, una función es continua si:

\[\lim _{x \to a} f(x) = f(a)\]

Clasificación de Discontinuidades

1. Removible

En este caso \(a\) no está definida en la función, es decir existe el límite finito \(L\) de \(f(x)\) en \(x = a\) pero \(f(x)\) no está definida en \(a\). La función puede modificarse adoptando como \(f(a)\) el valor \(L\) correspondiente, convirtiéndose así en una función continua en \(x = a\).

También se clasifica como removible la discontinuidad en la que no se cumple la condición (c) de la definición de continuidad, es decir, existen \(f(a)\) y , pero no coinciden. En este caso, puede salvarse la discontinuidad tomando como valor de la función el resultado del límite.

2. Salto

Existen los límites laterales pero son distintos.

3. Infinita (asíntotas)

Al menos uno de los límites laterales no existe.

Ir a GeoGebra

Determinando Continuidad

¿Cómo saber si la siguiente función es continua o no en \(x = 2\)?

\(f(x) = \dfrac{(2x+1)(x-2)}{(x-2)} \)

¿Necesitamos usar límites? Probemos para ver si se requiere.

Si evaluamos la función anterior en \(f(2)\), veremos que \(f(2) = \dfrac{0}{0} \), lo cual nos obliga a utilizar límites.

Actividad #1

Una función \(f\) se muestra a continuación.

1. Indica los intervalos en los que la función \(f\) es continua.

2. Identifica el tipo de discontinuidades y su ubicación en el eje \(x\).

3. La función está definida para todo número real, excepto cuando \(x\) vale:

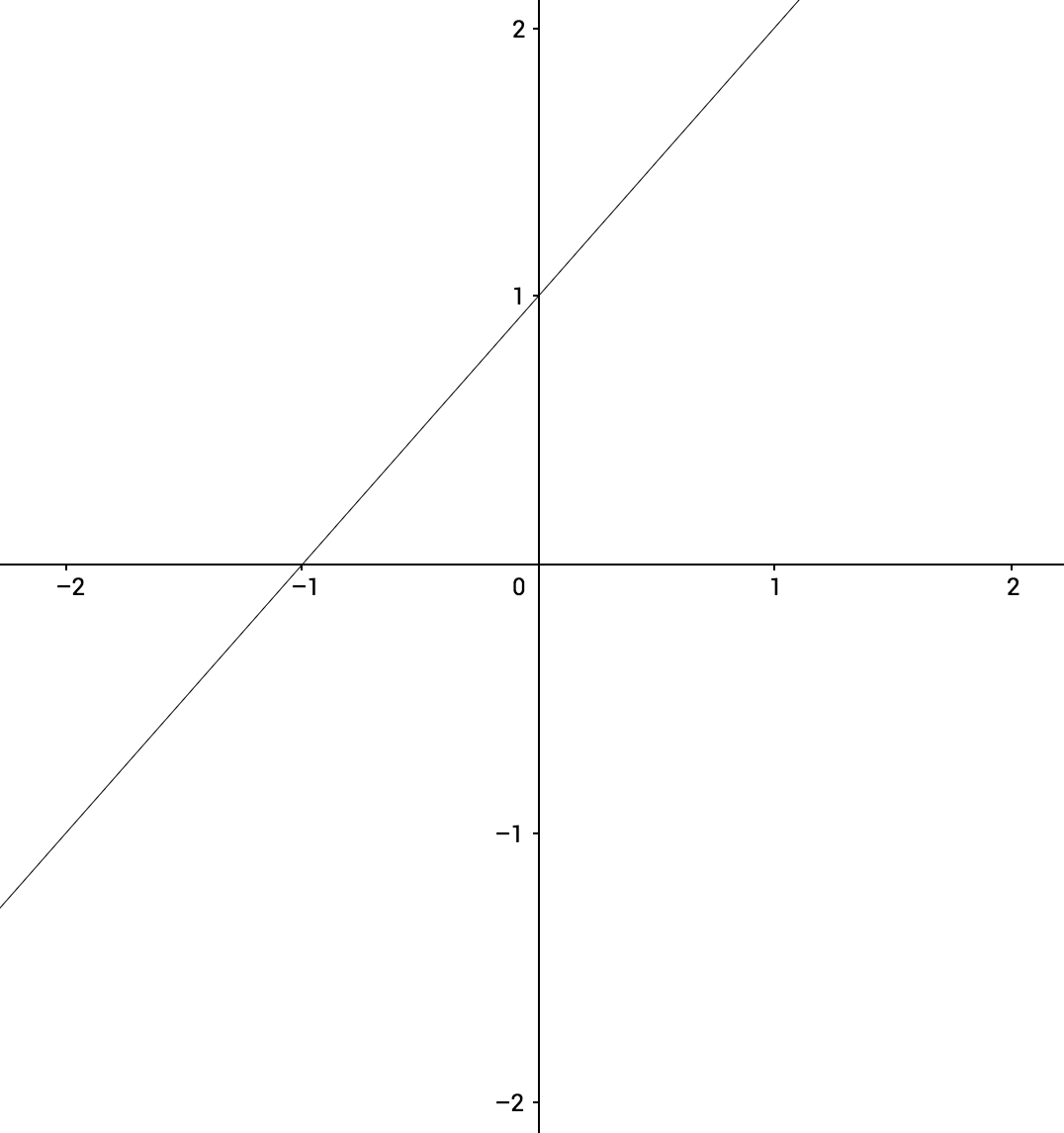

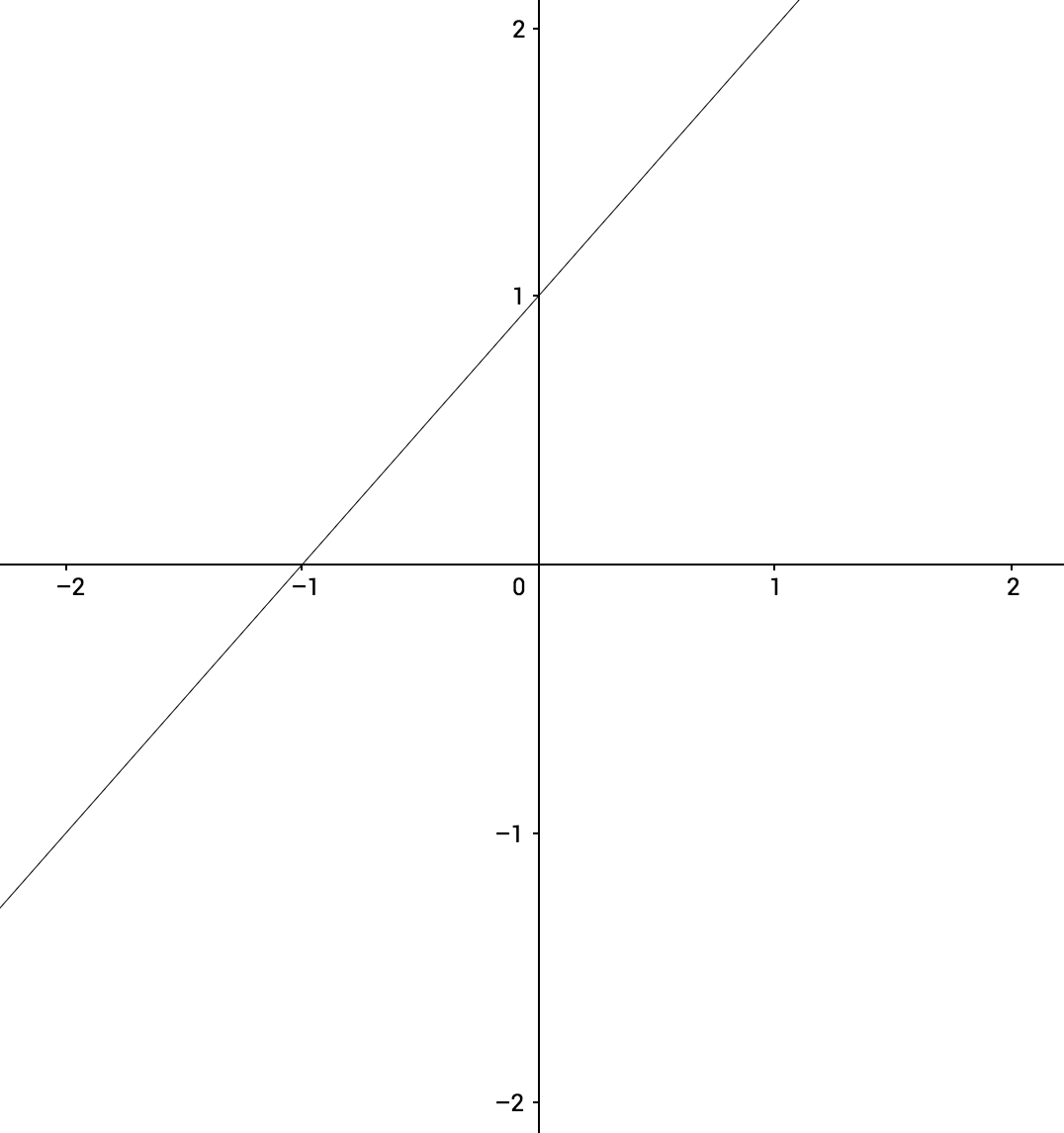

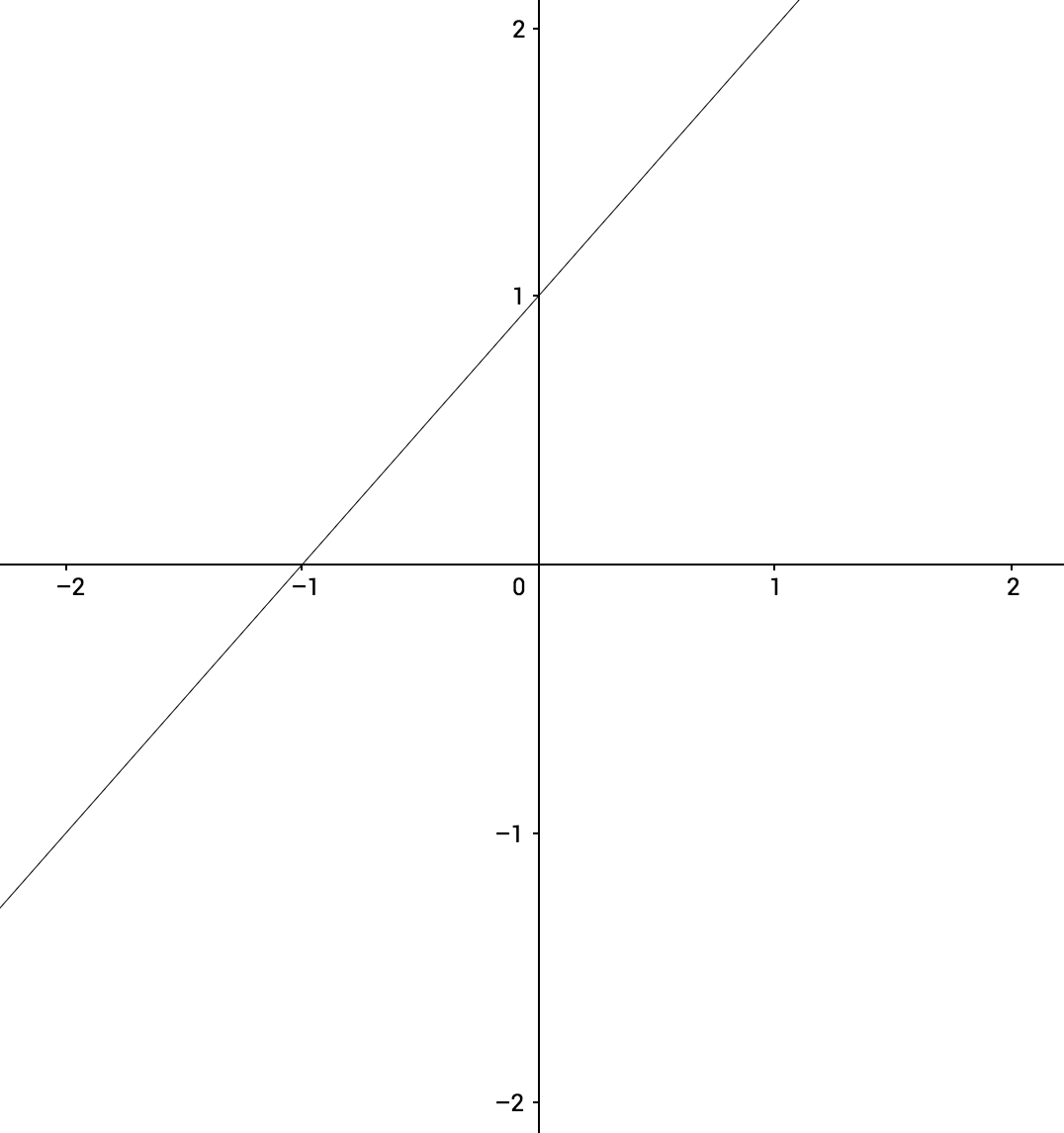

Evaluando Límites Numéricamente

$$ \lim_{x\to0} \ x + 1$$

$$(0) + 1$$

$$= 1$$

$$ \lim_{x\to0} \ x + 1 = 1$$

$$ \leftarrow f(x) $$

$$ f(x) = x+1 $$

$$\leftarrow x$$

$$x \rightarrow $$

Como la función es continua en \(x=0\) podemos emplear el método de sustitución \(x\) \(\rightarrow\)\(0\)

Evaluando Límites Numericamente

$$ \lim_{x\to0} \ f(x) = 1$$

$$ \leftarrow f(x) $$

$$ f(x) = x+1 $$

$$\leftarrow x$$

$$x \rightarrow $$

$$\text{¿A dónde se aproxima } f(x)$$

$$ \text{ conforme } x \text{ tiende a } 0? $$

$$ f(x) = x+1 $$

$$ \lim_{x\to1} \ x + 1$$

What happens as \(x\) approaches \(1\)?

$$(1) + 1 $$

$$= 2$$

$$ \lim_{x\to1} \ x + 1 = 2$$

By looking at the graph, what will be the \(\lim\) as \(x\to-1\)?

$$x \rightarrow 1$$

$$ \leftarrow x $$

Note that \(f(1)\) is defined:

\(f(1) = 2\)

Propiedades de Límites

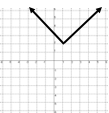

Limit of piecewise functions

$$\lim_{x\to0} $$

$$f(x) = x^2$$

$$f(x) = x+1$$

$$ f(x) = x^2$$

$$ f(x) = x+1$$

$$ \text{From negative infinity and up until } 0 $$

$$\text{just past 0 and unbound (up to infinity) } $$

The limit does not exist.

$$\text{so our function, made of two pieces, is: } $$

Limits of Piecewise Functions

$$\lim_{x\to0} f(x) = $$

$$\lim_{x\to0^{-}} f(x) = $$

$$\lim_{x\to0^{+}} f(x) = $$

$$\text{DNE}$$

$$ 0$$

$$ 1$$

$$\lim_{x\to0^{-}} \neq \lim _{x\to0^{+}}$$

$$\text{Since} $$

Evaluando Límites

$$\text{El caso }\dfrac{0}{0} $$

You might stumble find functions that will evaluate to be undefined upon direct substitution. This is known as the However, you should not automatically declare that the function is discontinuous. The 0/0 case is usually an indicator of further algebraic manipulation.

\[\dfrac{0}{0} \text{ case.}\]

We know that the result of any number \(a\) divided by \(0\) is not defined

Nonetheless, remember that we are interested in the values that are really close to \(a\), not \(a\) itself. So let's take a look at some examples to illustrate this situation.

Caso 1: Factorizar

$$ \lim _{x\to3} \dfrac{x^2+x-12}{x-3}$$

$$\Rightarrow \dfrac{0}{0} \text{ case}$$

(we factor)

$$=\dfrac{(x+4)(x-3)}{(x-3)}$$

$$\Rightarrow (x+4)$$

$$ \lim _{x\to3} \dfrac{x^2+x-12}{x-3} = 7$$

$$\Rightarrow (3+4) =7 $$

(we substitute again)

$$ \lim _{x \to 4} \dfrac{x-4}{\sqrt{x} -2}$$

Caso 2: Racionalizar

$$\dfrac{x-4}{\sqrt{x} -2}$$

$$\dfrac{\sqrt{x}+2}{\sqrt{x} +2}$$

$$\Rightarrow \dfrac{(x-4)(\sqrt{x} +2)}{(x -4)}$$

$$= {\sqrt{x}+2}$$

$$\Rightarrow {\sqrt{4}+2 = 4}$$

$$ \lim _{x \to 4} \dfrac{x-4}{\sqrt{x} -2} = 4$$

•

$$\Rightarrow \dfrac{0}{0} \text{ case}$$

\( (\text{we substitute again)} \)

\( (\text{we rationalize)} \)

Encontrando Límites

Example 1

$$\lim_{x\to-2} 3x^2+5x-9 $$

Example 2

$$\Rightarrow 12-19= -7$$

$$\lim_{x\to0} {(x+e^{x})}^{-1}$$

$$= \lim_{x\to0}\dfrac{1}{(x+e^{x})}$$

$$= \lim_{x\to-2} 3(-2)^2+5(-2)-9 $$

$$= \lim_{x\to-2} 12-10-9 $$

$$\lim_{x\to-2} 3x^2+5x-9 = -7 $$

$$= \lim_{x\to0}\dfrac{1}{(0+e^{0})}$$

$$\Rightarrow \lim_{x\to0}\dfrac{1}{1}=1$$

$$\lim_{x\to0} {(x+e^{x})}^{-1} = 1$$

Example 3

$$\lim_{x\to2} \dfrac{x^3-4x}{x^2-4} $$

Example 4

$$=\lim_{x\to2} \dfrac{x(x^2-4)}{x^2-4} $$

$$=\lim_{x\to2} {x} =2$$

$$=\lim_{x\to2} {x} $$

$$\lim_{x\to6} \dfrac{x^2+x-42}{-12+2x} $$

$$= \lim_{x\to2} \dfrac{(x+7)(x-6)}{2(x-6)} $$

$$= \lim_{x\to2} \dfrac{(x+7)}{2} $$

$$ \Rightarrow \lim_{x\to2} \dfrac{(2+7)}{2} =\dfrac{9}{2} $$

$$\lim_{x\to6} \dfrac{x^2+x-42}{-12+2x} = \dfrac{9}{2} $$

$$\lim_{x\to2} \dfrac{x^3-4x}{x^2-4} = 2 $$

Example 5

$$\lim_{x\to-4} x^2+\sqrt{-4x} $$

Example 6

$$\Rightarrow 16+ 4= 20$$

$$\lim_{x\to0} {(x+1)^2}\cos{(\dfrac{x}{1-x})}$$

$$= \lim_{x\to-4} (-4)^2+\sqrt{-4(-4)} $$

$$= \lim_{x\to-4} 16+\sqrt{16} $$

$$\lim_{x\to-4} x^2+\sqrt{-4x} = 20$$

$$= \lim_{x\to0} {((0)+1)^2}\cos{(\dfrac{0}{1-0})}$$

$$\Rightarrow \lim_{x\to0} {(1)^2}\cos{(0)}$$

$$\Rightarrow \lim_{x\to0} {(1)}{(1)}=1$$

$$\lim_{x\to0} {(x+1)^2}\cos{(\dfrac{x}{1-x})}=1$$

Límites que tienden a infinito

Limits Involving Infinity \(\infty\)

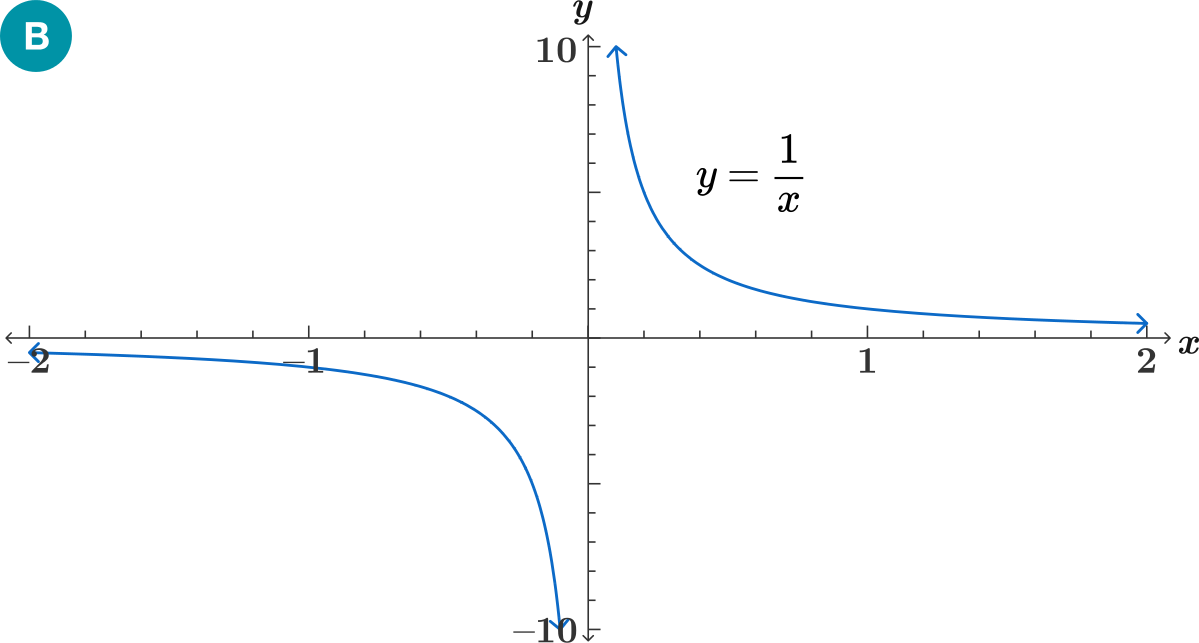

Before jumping into limits involving infinity, let's recall what indeterminate forms are and how to "evaluate" expressions that oscillate near these values. For instance, let's take a look at the expression \(\dfrac{1}{x}\).

Let's start with \(x=1\), plotting each time a greater value for \(x\)

\(\dfrac{1}{10000000}= 0.0000001\)

\(\dfrac{1}{1}=1\)

\(\dfrac{1}{100}=0.01\)

\(\dfrac{1}{10000}=0.00001\)

Do you see where the value of \(\dfrac{1}{x}\) is going? What would \(\dfrac{1}{x}\) be if \(x=1,000,000,000\)?

The expression \(\dfrac{1}{x}\) would get closer and closer to zero as \(x\) gets bigger and bigger. We can represent this mathematical behavior by assigning this huge number an infinite value: \(\infty\).

\(\text{ Any number divided by } \pm\infty \text{ approaches } 0\)

\[\lim_{x\to\infty}\dfrac{a}{x}=0 \]

\(\dfrac{a}{\infty}\ne0 \)

but!

'Intuitive' Forms:

\[ \dfrac{a}{\infty} = 0\]

\[ \dfrac{\infty}{a} = \infty\]

\[ a^{-1}=\dfrac{1}{a}\]

\[a^{\infty}=\infty\]

\[a^{-\infty}=\dfrac{1}{a^{\infty}}\]

\[a*\infty=\infty, a\ne 0\]

\[ \infty-\infty\]

\[a^{0}=1\]

\[\infty^{\infty}\]

\[\infty^{0}\]

\[0^{0}\]

\[1^{\infty}\]

\[\dfrac{0}{0}\]

\[0*\infty\]

Indeterminate Forms:

\[ \dfrac{a}{0^{+}} = \infty\]

\[ \dfrac{a}{0} = \text{und. }\]

\[ \dfrac{a}{0^{-}} = -\infty\]

Let's consider

What happens as \(x\to0\)

We know that

\( \lim _{x\to0} f(x) \text{ does not exist since}\)

But what happens when \(x\to-\infty\) ?

\[\lim_{x\to-\infty } \dfrac{ 1}{x}\]

\[\Rightarrow \dfrac{ 1}{(-\infty)}\]

\[\lim_{x\to-\infty } \dfrac{ 1}{x}=0\]

Similarly, when \(x\to\infty\)

\[\lim_{x\to\infty } \dfrac{ 1}{x} = \dfrac{1}{\infty} = 0\]

\[f(x) = \dfrac{1}{x} .\]

\(\lim _{x\to0^{-}} \ne \lim_{x\to0^{+}}\)

\[\lim_{x\to\infty } \dfrac{ 1}{x}=0\]

Analytical Approach

\[f(x) = \dfrac{9}{(x-3)^5}\]

\[\lim _{x\to3^{-}} f(x) = \]

\[\lim _{x\to3^{+}} f(x) = \]

\[\lim _{x\to3} f(x) = \]

Let's use our intuition first. If \(x \rightarrow 3^{-} \), then the denominator of \(f(x)\) will be negative, \(x - 3 < 0\), and progressively smaller as we get closer to 3 from the left. This looks like the form \(\dfrac{a}{0^{-}} \) , and even though the denominator will never be 0, we know

\[\lim _{x\to3^{-}} f(x) = \dfrac{9}{(2.99999-3)} = \dfrac{1}{0^{-}} = -\infty \]

\[\lim _{x\to3^{+}} f(x) = \dfrac{9}{(3.00001-3)} = \dfrac{1}{0^{+}} = \infty \]

\(\infty\)

\(-\infty\)

\(\text{DNE }\)

\(e^{\pm\infty}\)

\[\lim _{x\to\infty} e^x = \infty \]

Trick: \(e^{-\infty} = \dfrac{1}{e^{\infty}}\) and any number \(a^{\infty} = \infty\)

\[\lim _{x\to\infty} e^{-x} = 0 \]

\[\lim _{x\to-\infty} e^{x} = 0 \]

\[\lim _{x\to-\infty} e^{-x} = \infty \]

\[\lim_{x\to\infty} e^{-x}\]

\[\lim_{x\to-\infty} e^{x}=\]

\[\Rightarrow \frac{1}{e^{\infty}}\]

\[\lim_{x\to\infty} e^{-x}=0\]

\[e^{-\infty}\]

\[\Rightarrow \frac{1}{e^{\infty}}\]

\[\lim_{x\to -\infty} e^{x}=0\]

\[=\frac{1}{e^{x}}\]

\(3. \ f(x) = \dfrac{4x^4-3x^3+3x^2-3x+3}{2x^2+5x^3+2x^4} \)

\(2.\ f(x) = -(x^3-x)^{-2}\)

Find \(\lim_{x\to\infty}\) and \(\lim_{x\to-\infty}\) for the following functions:

\(1. \ f(x)= e^{2x^2-x+1}\)

\(4.\ f(x) =\dfrac{\sin{3x}}{x}\)

\[ \lim_{x\to0} f(x) =\dfrac{\sin{3x}}{x} \ ?\]

how about

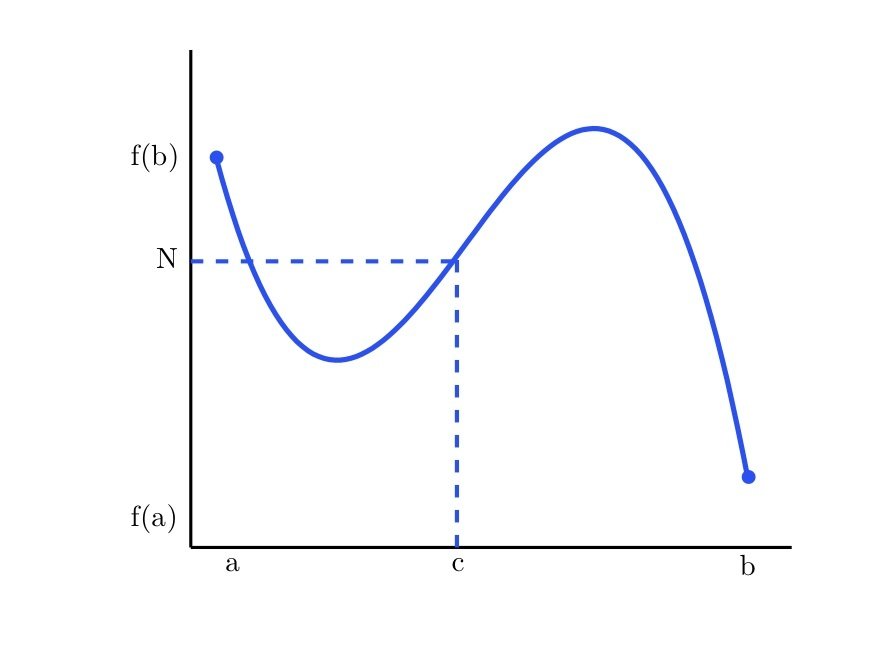

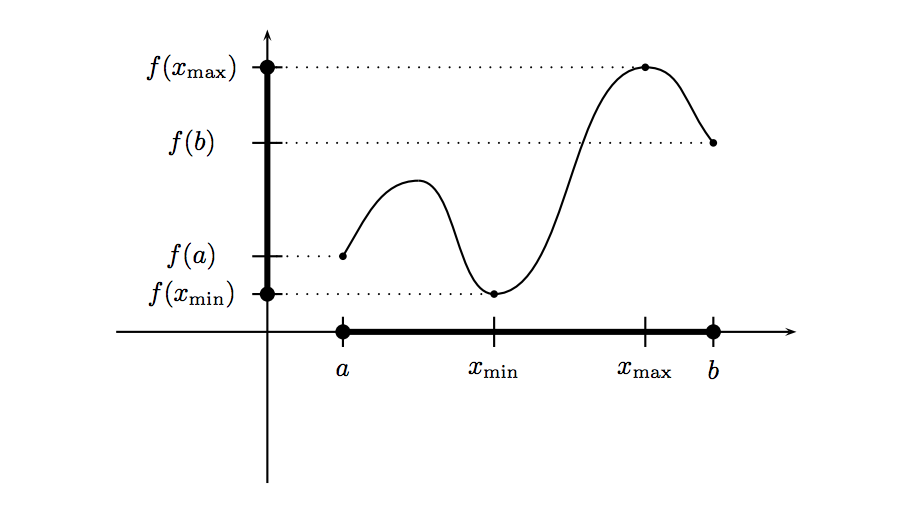

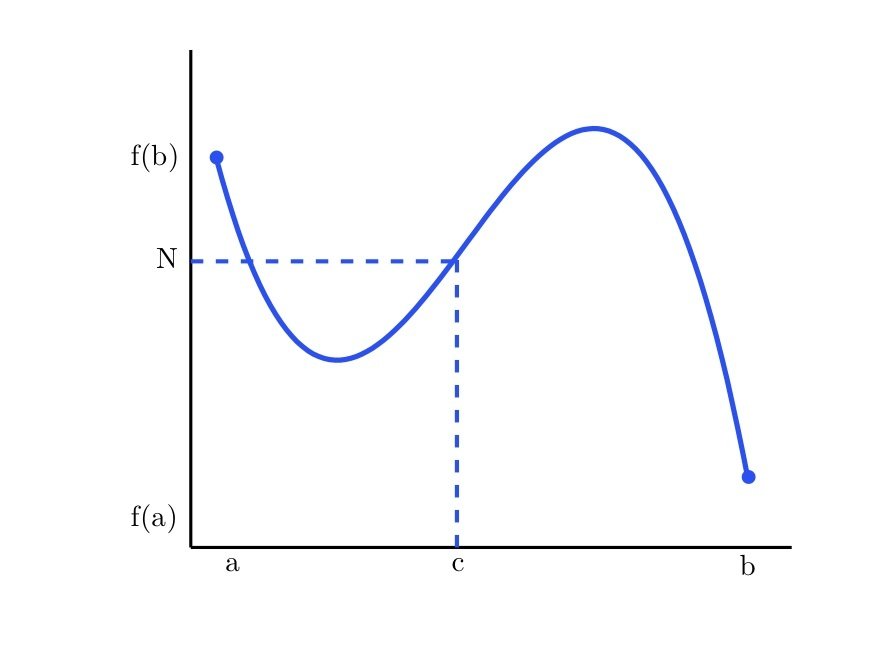

Intermediate Value Theorem

Domain:

$$[a,b]$$

Continuous on: $$[a,b]$$

$$\text{abs. minimum }$$

$$(x_{max}, f(x_{max}))$$

$$\text{abs. maximum }$$

Intermediate Value Theorem

For any function \(f(x)\) that is continuous on \([a, b]\), and \(f(a)\) and \(f(b)\) exist, (at each end of the interval), then some value \(c\) must exist between \(a\) and \(b\) such that \(f(b)>f(c)>f(a)\)

\(f(c)\)

\(f(a)\)

\(f(b)\)

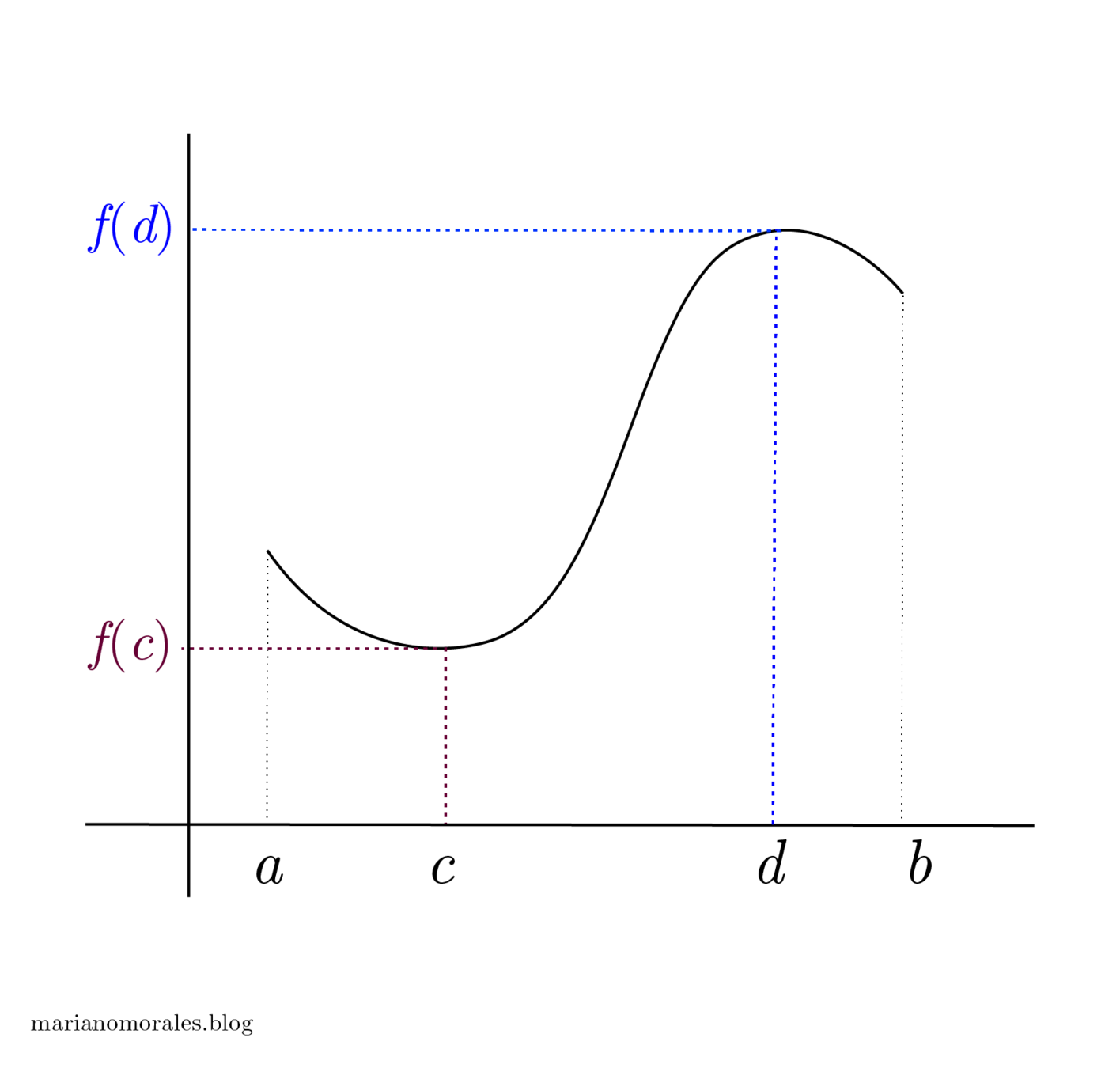

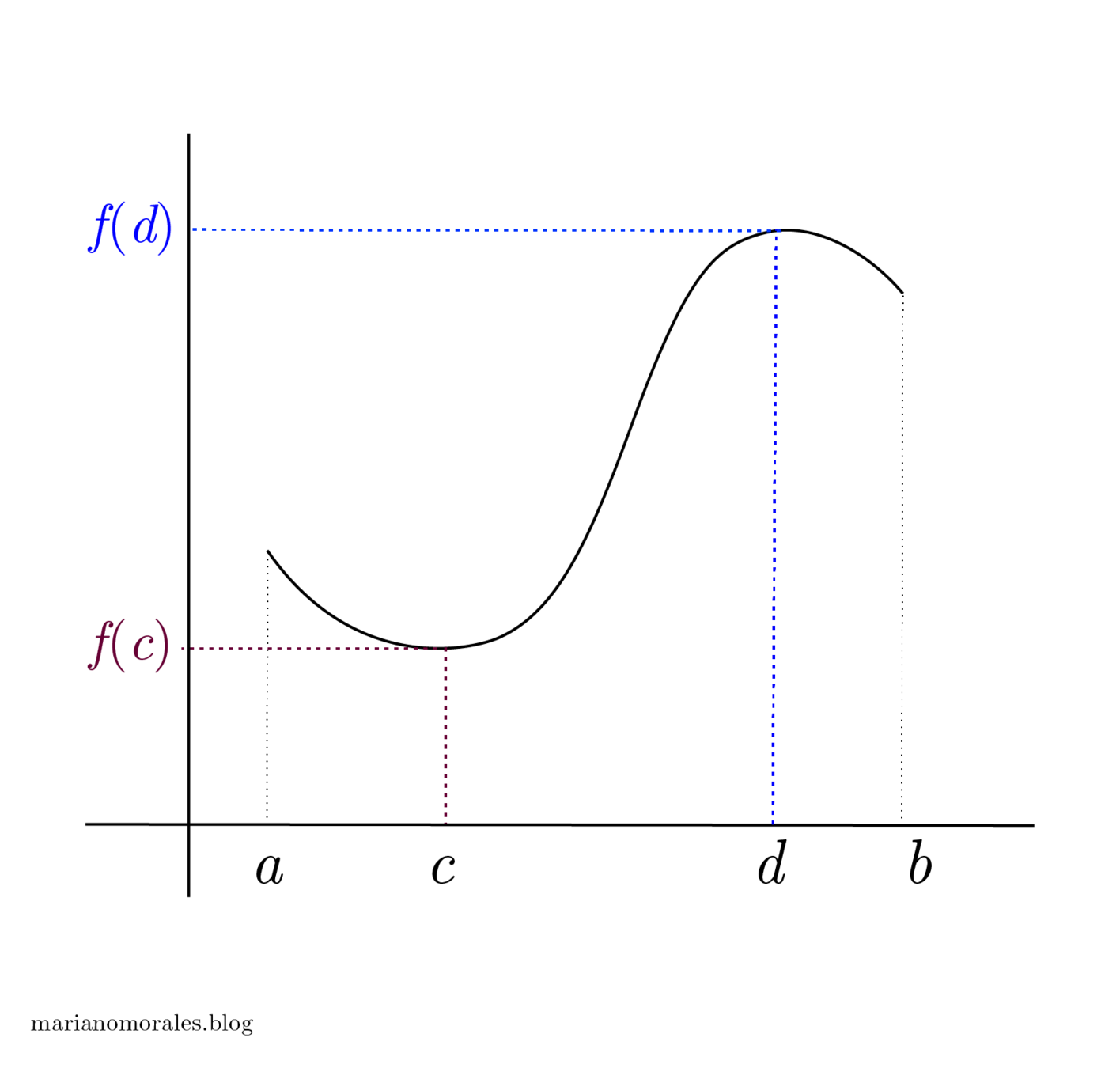

Extreme Value Theorem

There is at least one point \(c\) in the interval \([a,b]\) such that \(f(c) \leq f(x) \) for all \(x\) in \([a,b]\) and there is at least one point \(d\) in the interval \([a,b]\) such that \(f(d) \geq f(x)\) for all \(x\) in \([a,b]\).

\(f(x)\)

Extreme Value Theorem

There is at least one point \(c\) in the interval \([a,b]\) such that \(f(c) \leq f(x) \) for all \(x\) in \([a,b]\) and there is at least one point \(d\) in the interval \([a,b]\) such that \(f(d) \geq f(x)\) for all \(x\) in \([a,b]\).

Consider the function \(f(x)\). Assume it is continuous on \([a,b]\). According to The Extreme Value Theorem, the function \(f\) will have a maximum value and also a minimum value within [a,b]

\(f(x)\)

The Derivative

What the hell is a derivative, anyways?

are all the derivative of \(f(x)\):

\[f'(x) = \lim _{h\to0}\dfrac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}\]

The slope of the tangent line

\[m_{tan} = \dfrac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\]

and the instantaneous rate of change

\[\lim_{\Delta x\to0}\dfrac{f(x+\Delta x) - f(x)}{\Delta x}\]

...yup, we are bound to have some fun! :)

Examples in Spanish

Differentiation Rules

(beta, in construction)

The Integral

(beta, still in construction)

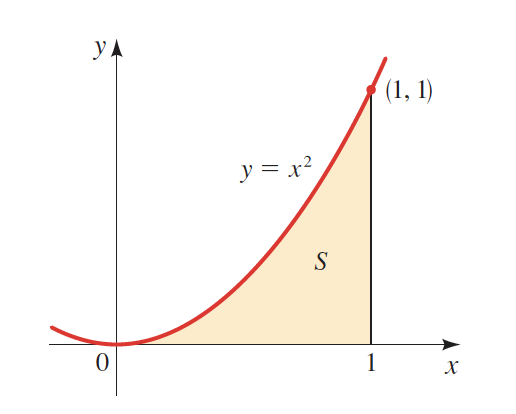

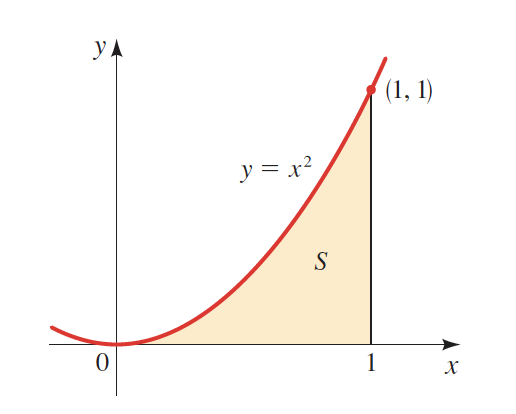

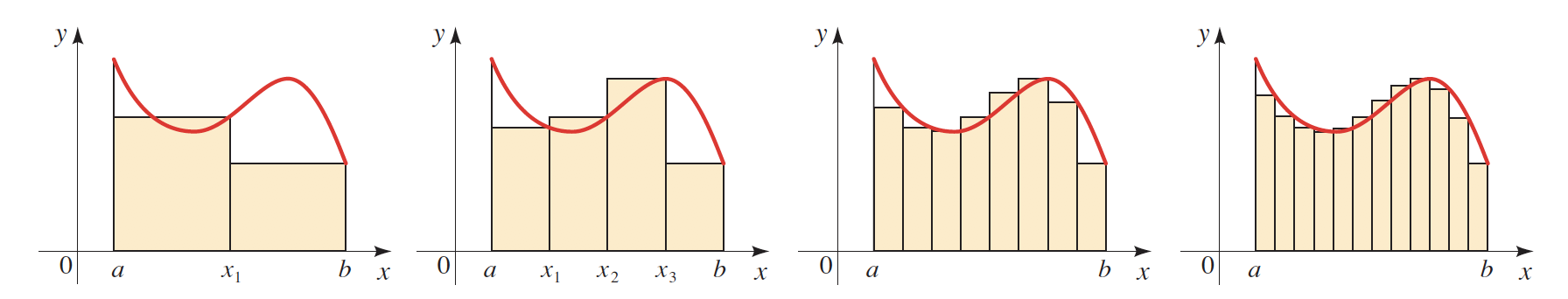

The Area Problem

Imagine you want to find the area below the curve shown at the right.

Of course, there is no formula that can nearly be fixed for every area under every curve. However, we can approximate, to an infinitesimal point, the total area if we break it down into rectangles.

Let's see what I mean by this.

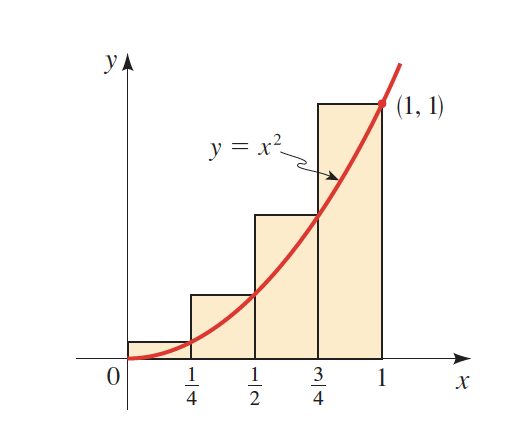

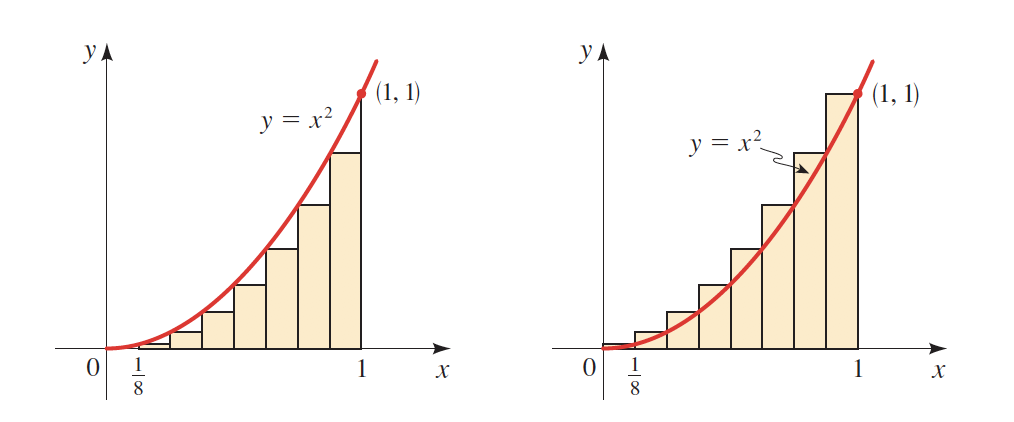

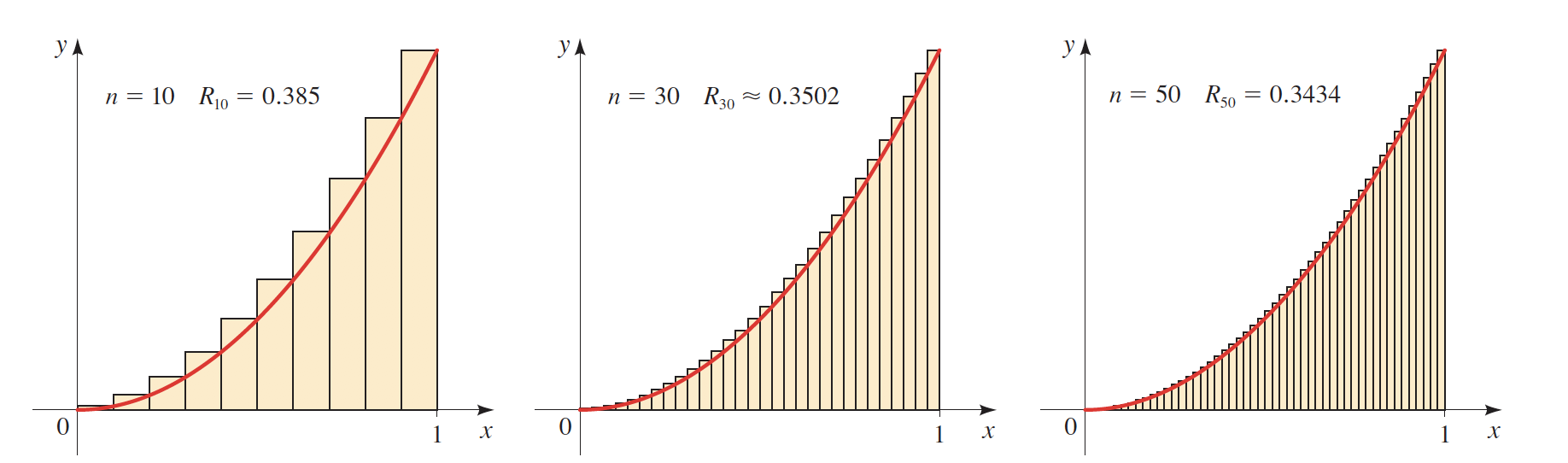

The Sum of the Areas

As observed in both curves, the more rectangles (\(n)\) we draw, the more accurate will be our result.

\(n=4\)

\(n=4\)

\(n=8\)

\(n=14\)

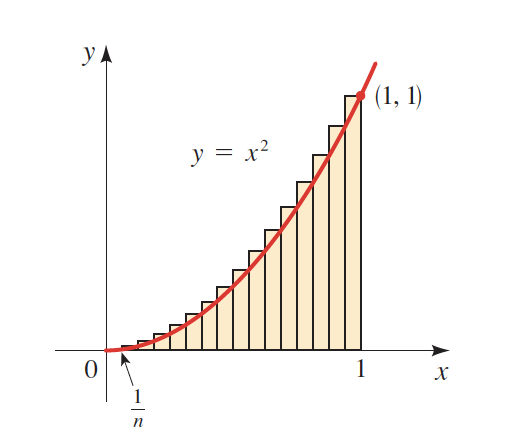

Limits in Integration

As we anticipated earlier, limits are also a fundamental concept behind integration. As a matter of fact, the limit is the most important concept in all calculus. Let's see the role that the limit plays in integration.

What is the base of each rectangle that is drawn between 0 and 1?

If we draw 5 rectangles \(n=5\), then the base of each rectangle will be \(\dfrac{1}{5}\) or \( \dfrac{1}{n}\). The height will vary, but the base will remain constant for every triangle.

Furthermore, we can find the area of each rectangle and add them up to come up with the exact area. The more rectangles we draw, the smaller will be the base of each triangle, but the more accurate we will get.

Solving the area problem

In the make as of July 31st, 2018

Title Text