Future of Storytelling

Disruption

Today’s networked digital technologies differ fundamentally from the centralized media systems that dominated the 20th century.

Legacy media industries

simply extended familiar ways of thinking to the Internet only to find income elusive, user-bases unpredictable, and competition from digital-first upstarts fierce.

Adaptation

Several quality journalism organizations have responded by experimenting with new, digitally native forms of storytelling

Begin with the user

Thinking about user experience, understanding user behavior, and being in dialogue with the intended public at the beginning of an interactive documentary or journalistic project is fundamental to reaching and engaging with that public.

Let Story Determine Form

The story and materials should determine the storytelling techniques employed, and not vice-versa; interactivity and participation provide an expanded toolkit that can enhance clarity, involvement, meaning, and “spreadability,” but they are not one-size-fits-all solutions.

Experiment and Learn

Interactive and participatory documentaries can provide research and development opportunities for journalism organizations, which may then adapt relevant tools, techniques, and experiences for their future work.

Collaborate Across Borders

In an era when word, sound, and image flow together into one digital stream, media institutions fare better when they partner with like-valued organizations, form interdisciplinary teams, and co-create with their publics.

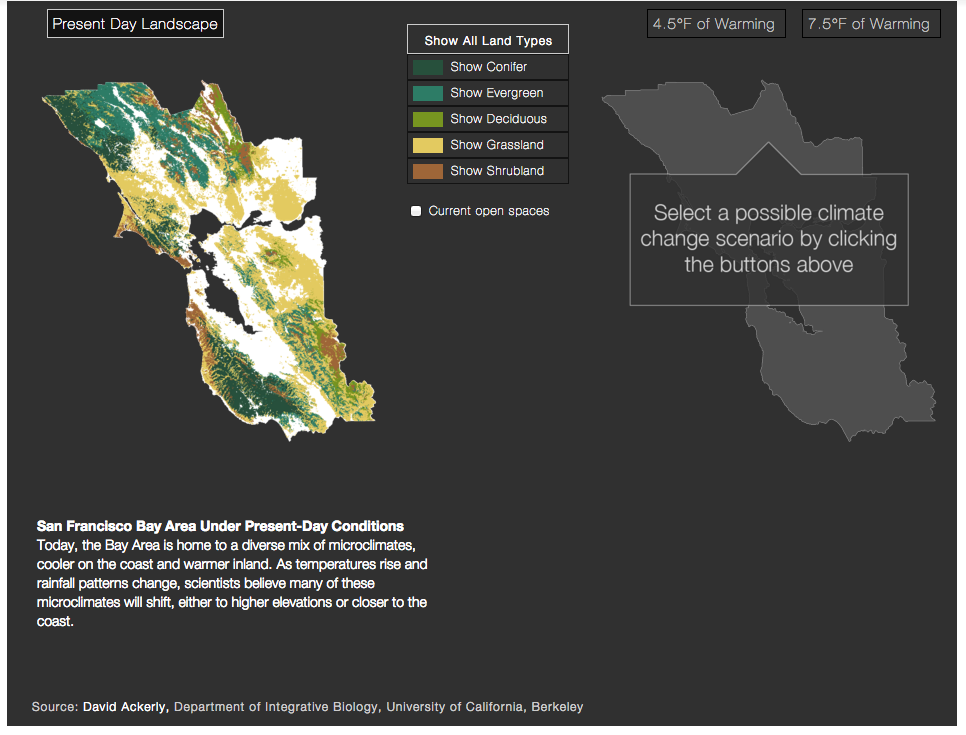

Visualizing a Warmer Future for Bay Area Open Spaces

Reported by KQED's Lauren Sommer with the support of a media fellowship from the Bill Lane Center for the American West, the story included two interactive graphics produced in collaboration with the Center's Creative Director for Media and Communications, Geoff McGhee, and the postdoctoral scholar and ecologist Maria Santos.

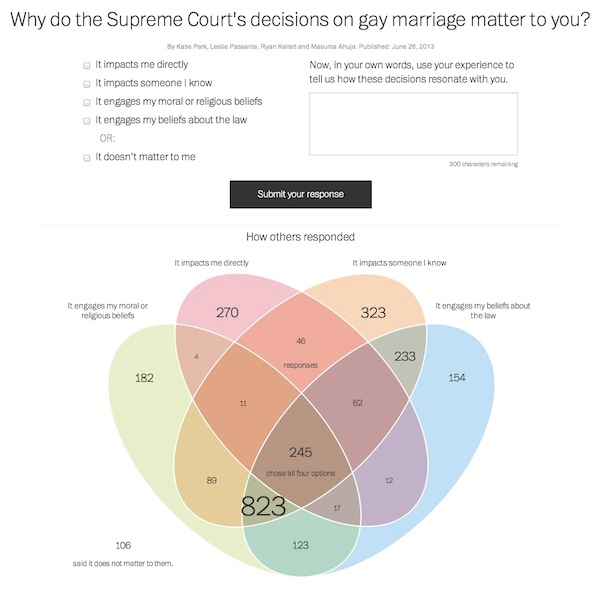

Shape Conversations

Interactivity and user participation can enable and inform the connection between audiences and sources, helping journalism to shape conversations in addition to defining truths.

Use archives creatively

Legacy journalism organizations can make much better use of a defining asset—their archives—to build deep, interactive story environments, distinguishing their voices in a crowded news environment and empowering their users to explore how events and their coverage take shape.

Michel Setboun - French Photojournalist - shot the 1979 Iranian Revolution

40 of his images are used in 1979 Revolution Game

Consider long-term impact

A cost-benefit analysis of interactive and participatory storytelling in journalism settings should include not only audience reach and impact, but also organizational innovation in the form of new teams, processes, and tools that can be integrated into other parts of the newsroom

A well-informed citizenry has never been more possible. We have tools, platforms, and petabytes of information at our disposal.

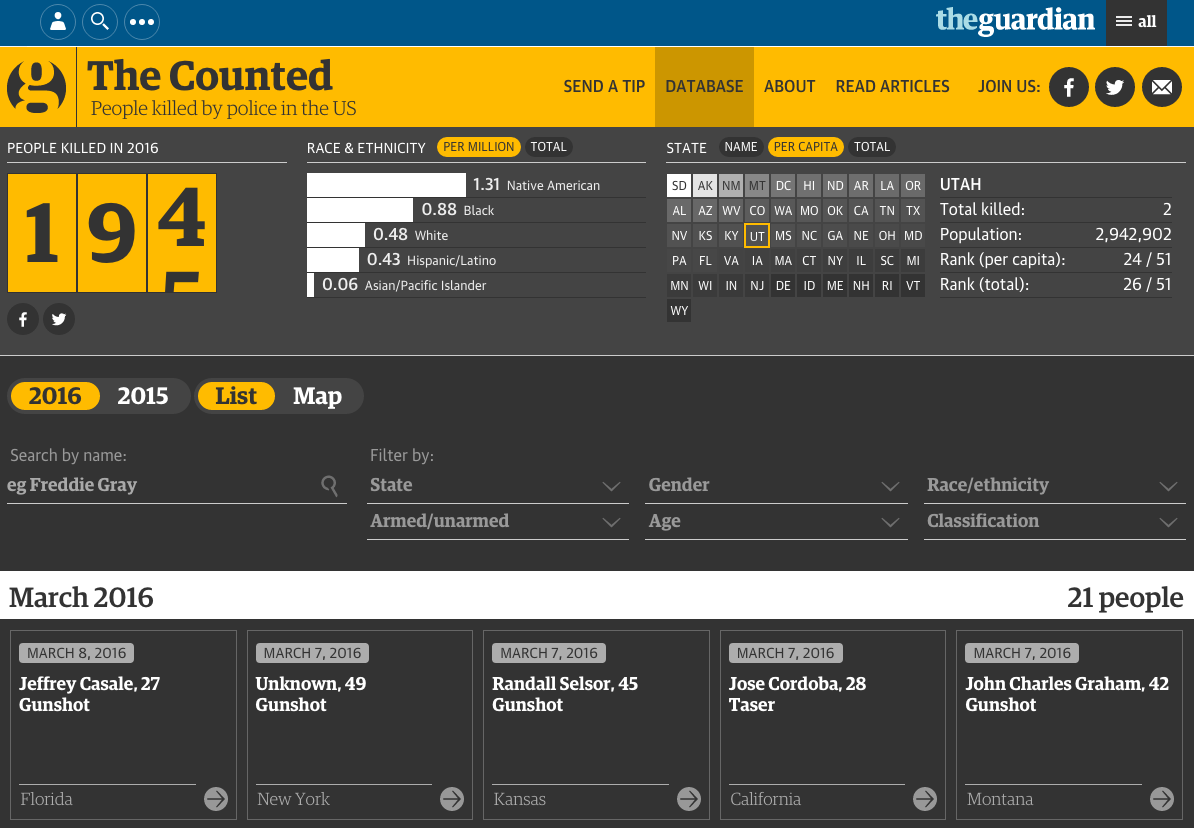

Today’s media enable user-generated stories to complement the mainstream press, offer powerful opportunities to analyze and display data, and provide engaging new ways to spread information

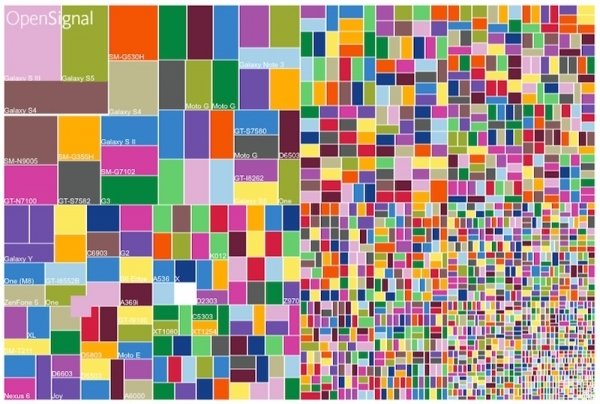

Fragmentation

Studies point to the collapse of existing commercial business models, aging traditional readerships, the dominance of the small screens/mobile, ever-faster news cycles, and the growing “noise” produced by a new generation of digital native news startups.

Experimentation

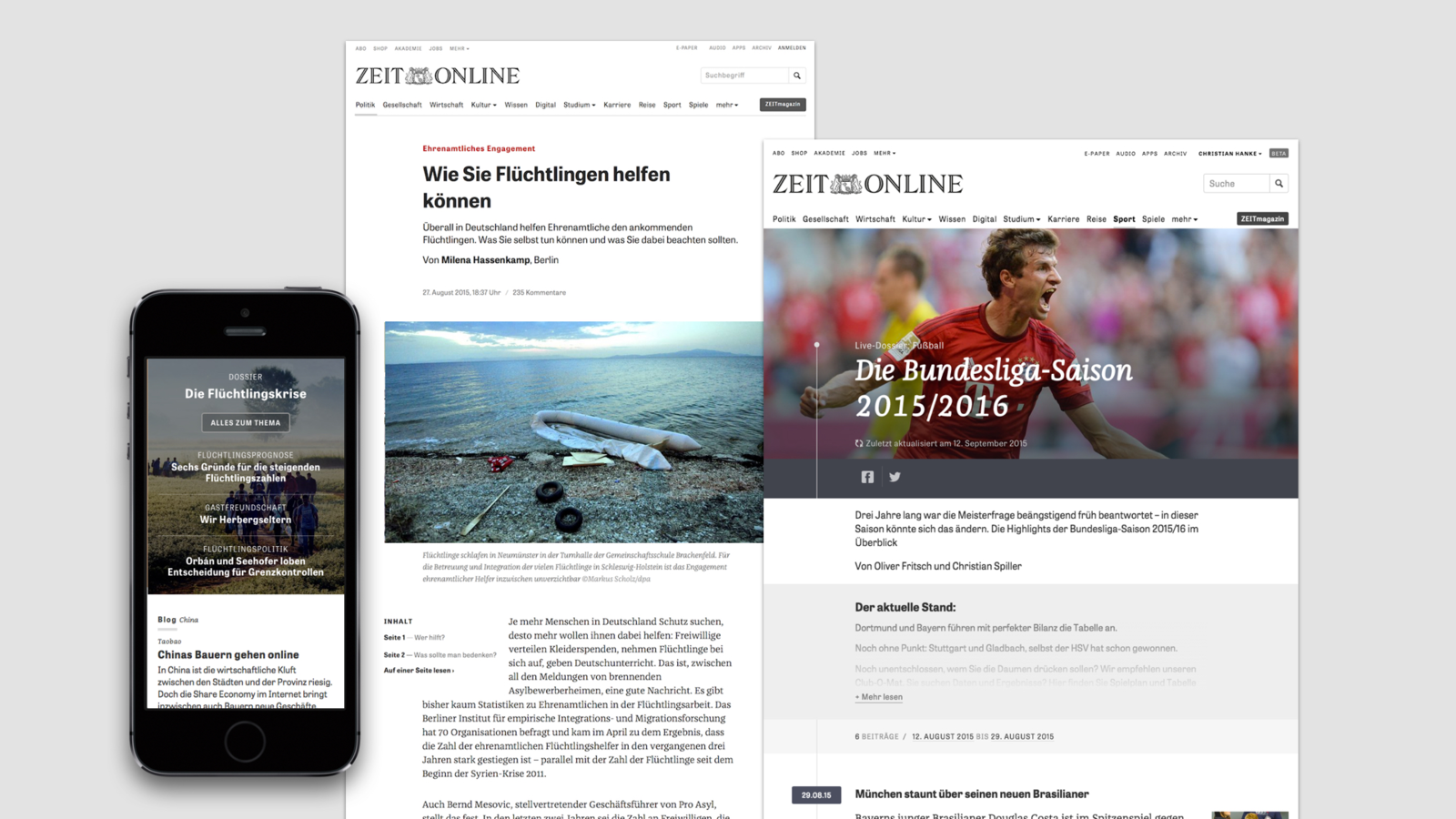

A few pioneering journalism organizations such as The New York Times, The Guardian, The Washington Post, AIR, Al Jazeera, Frontline, POV, Zeit.online and the University of North Carolina’s News 21 “Powering a Nation” program are exploring new kinds of stories and storytelling processes.

Doc Vs. Journalism

Documentary and journalism largely share the same ethos and commitments to truth-telling, sense-making, and explaining. But they have taken form in very different institutional settings. Journalism is professionalized and bound by tradition, codes of ethics, and institutional frameworks.

Documentary

A relative newcomer, documentary harkens back in a narrow sense to a particular medium (film) at a particular moment (the 1920s). Narrative in structure, embodying an authorial point of view, embracing a visual aesthetic sensibility, documentary is historically associated with characteristics that put significant emphasis on ritual.

Documentary

Documentary has a deep history of working across media borders, which has led to today’s considerable innovation in both interactive and participatory documentary forms

Interactive Docs

Gerry Flahive, producer of the National Film Board of Canada’s Highrise series, said, “If the growth of interactive documentary does anything, I think it will open our eyes to the hundreds of possibilities of telling stories in original ways, and re-defining what a story is, what an audience is, and what a maker is."

Particpatory Doc

- techniques for telling engaging and immersive interactive stories that draw on the documentary tradition of narrative, characters, and an aesthetic sensibility

- point of view, a rhetorical stance as “conversation-starter” and enabler of ritual in the process of communication

- ways of imagining, addressing, and working with the audience associated with the documentary, including co-creation and user generated content

Particpatory Doc - cont.

- changes to the production pipeline that draw on and recombine methodologies derived from documentary, journalism, and information technology

- uses of graphically-rich interfaces, moving image and sound, navigational systems, and dynamic data

- techniques can be used with good effect on mobile, small-screen platforms.

Media ecosystem characterized by fragmentation and plenty

Why documentary? As the Center for Investigative Reporting’s Cole Goins puts it, journalism “could be a play, a poem, a 5,000 word story. It could be an animation, it could be a data app. It could be whatever you want it to be.”

Documentaries actually come from a multimedia storytelling tradition, often with a distinctive point of view and notions of character, audience, aesthetics, and even impact differ from mainstream journalism.

And yet, like the best examples of long-form investigative journalism, interactive documentaries are capable of relaying deep and complex information in compelling ways.

Lego Blocks

A modular approach has significant advantages when designing stories for small screens that enable their users to move from simplicity to depth as they follow their interests, linking units together, Lego-style, into a larger structure in the process.

Narrative units are easily shared in a socially-networked economy. This maps onto an emergent behavior known as “unbundling,” in which users and producers dismantle larger integral texts into self-contained fragments or segments such as webisodes, mobisodes, viral videos, and digests.

Ways of engaging

and immersing the audience

According to Sandra Gaudenzi, there are three different levels of interactivity that determine the type of i-doc.

The interactivity is either:

- semi-closed (the user can browse but not change the content)

- semi-open (the user can participate but not change the structure of the interactive documentary)

- completely open (the user and the interactive documentary constantly change and adapt to each other)

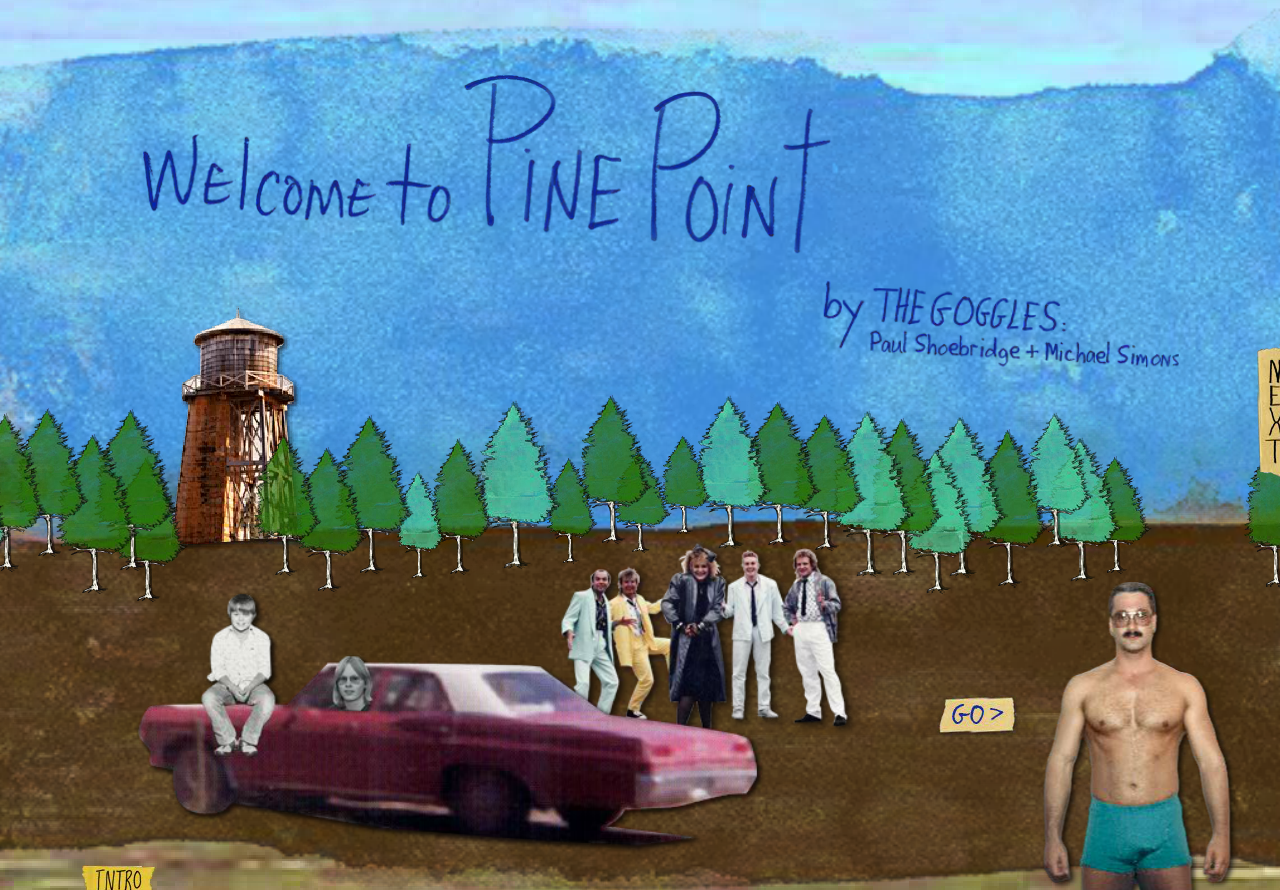

Welcome to Pine Point

A multimedia portrait of the disappeared Canadian mining settlement of Pine Point by one of its former residents.

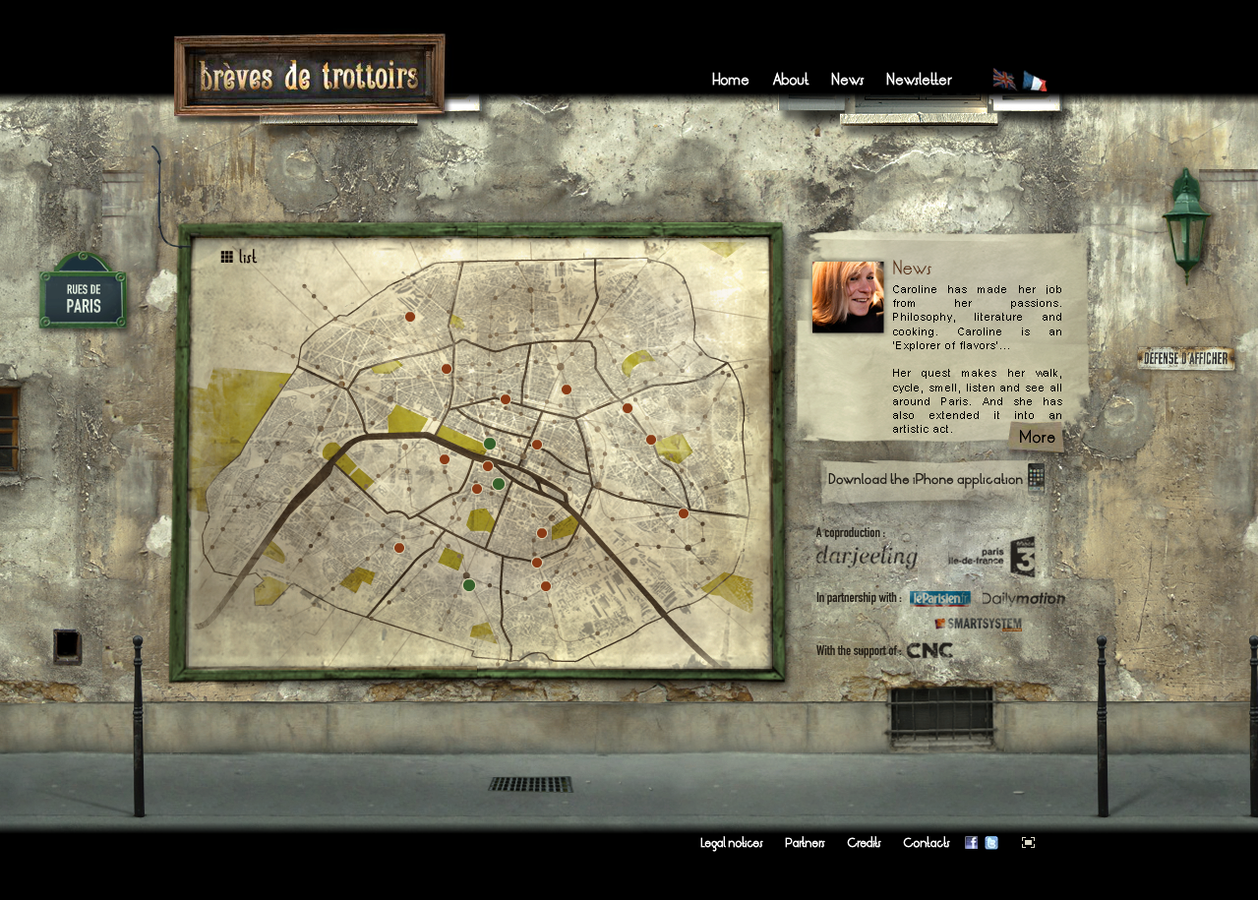

Brèves de Trottoirs

A Multimedia Guide To Paris

How do you map the life of a city? A Web documentary from writer Olivier Lambert and photojournalist Thomas Salva, “Brèves de Trottoirs,” (literal translation: “Sidewalk Shorts”) aims to find out. Their videos of Parisians with interesting backstories has appeared online and on television, and is in the process of becoming a full-length documentary film. (Even in French, the visuals provide a tremendous sense of the people and the city, but for a partially English-language version of the material, click on the British flag at the top of the home page.)

http://paris-ile-de-france.france3.fr/brevesdetrottoirs/#/intro

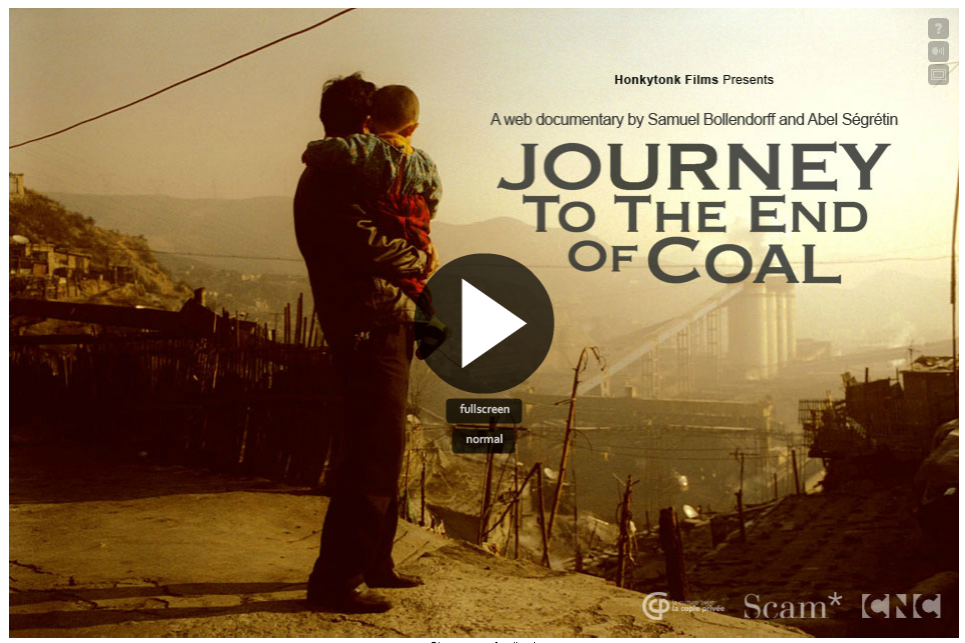

Journey to the End of Coal

This web documentary was made in 2008 by French production company Honkytonk Films ( directors Samuel Bollendorff and Abel Ségrétin).

This project explores the very poor working conditions of Chinese coal miners and investigates on the daily death that occur in those mines – deaths that never get reported by the media. Following a montage of stylish photos linked by an explanatory scrolling text, you are positioned in the role of an investigator that travels in the coal region and meets local people.

Your journey begins in Datong which is located just a couple hours away West from Beijing. You travel from there all around the region and visit its major coal mines, from the “best” state-owned complex to the worst private coal plants.

In and around the coal mines, you get the story first hand from the mingong, the rural migrants traveling their country looking for work.

Soul Patron

Follow your guide Tokotoko, an animated bunny, through Japanese shrines and city streets on a poignant exploration of Japanese culture and mythology.

Prison Valley

This web doc is the result of months of investigative work by two French journalists, Dufresne and Brault, and the distillation of thousands of photographs, hours of audio and video, and an eye-watering number of statistics.

Prison Valley invites users to check into a room at the motel with a personal Facebook or Twitter account, and then continue the journalists’ journey into the valley.

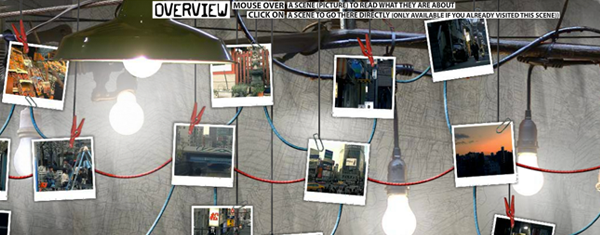

Man With The Movie Camera

Man With a Movie Camera: The Global Remake

is a participatory video shot by people around the world who are invited to record images interpreting the original script of Vertov’s Man With A Movie Camera and upload them to this site.

Software developed specifically for this project archives, sequences and streams the submissions as a film. Anyone can upload footage. When the work streams your contribution becomes part of a worldwide montage, in Vertov’s terms the “decoding of life as it is”.

This website contains every shot in Vertov’s 1929 film along with thumbnails representing the beginning middle and end of each shot.

http://dziga.perrybard.net/

Quipu Project

This interactive documentary provides a platform for victims of the involuntary sterilization campaigns under Peruvian President Fujimori in the 1990s.