C++ Course

Templates

Objectives

- Function template

- Motivation

- Syntax

- Multiple types

- Constraints

- Class template

- Syntax

- Constant, Defaults

- Specialisation

- Member function

- Template method in template class

Function tempate - motivation

int swap(int& first, int& second)

{

int tmp(first);

first = second;

return second = tmp;

}If we have a certain algorithm that we coded for 1 type

and we would like to extend it to other type. Without templates we will have to resort to coding the algorithm for each of the types. or alternatively work with generic pointer to pointers.

void* swap(void** first, void** second)

{

void* tmp(*first);

*first = *second;

return *second = tmp;

}Function template - motivation

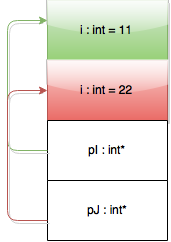

To explain the C style implementation

We need to understand that

1. We must work with pointers but we can not just supply the address of i or j (&i, &j), because we have no way of swapping i and j directly. So are required to introduce 2 more variables pI & pJ

2. It's not enough to send pI and pJ by value (that is the same as sending &i and &j, we would like to update the value of pI and pJ hence we send their address and cast it to a generic pointer (void**)

In C++ the introduction of references we can simplify the function to the following signature.

void* swap(void*& first, void*& second);

Still, far from elegant and given that we now have templates we don't need to use such incompressible & error prone syntax.

Function template - motivation

Disadvantages of C Style generic programming

- Code is more difficult to program/read and maintain

- Casting to pointer to void (generic pointers) are required = no type safety can be policed by the compiler

Function template - syntax

Templates are introduced to generalise an algorithm to multiple types

template <class T>

T swap(T& first, T& second)

{

T tmp = first;

first = second;

return second = tmp;

}Instantiation of the template functions is generated per using type

int i(10), j(20);

swap(i, j); // swap is called with integers

string s1("One"), s2("two");

swap(s1, s2); // swap is called with strings

swap(s1, i); // error: type of s1 is not equal to type of s2This may result in code bloat, when .

It is possible to demand the compiler instantiate explicit type.

swap<double>(i, j);Function template - multiple types

It is possible to have more than 1 generic type

int add(int first, int second)

{

return first + second;

}

template <class T1, class T2>

T1 executeOperation(const T1& first, const T1& second, T2 predicate)

{

return predicate(first, second);

}

int main()

{

cout << executeOperation(1, 2, add);

}Function template - constraints

string addString(const string& s1, const string& s2)

{

return s1 + " " + s2;

}

template <class T1, class T2>

T1 executeOperation(const T1& first, const T1& second, T2 predicate)

{

return predicate(first, second);

}

int main()

{

cout << executeOperation(string("Hello"), string("World"), addString);

}With templates implicit conversion doesn't take place.

Note that we rare required to send string, char[] otherwise T1 will be char[], T1 being also the return value will not be compatible the string type returned from predicate.

Template function - constraints

template <class T>

T min(T first, T second)

{

return first <= second ? first : second;

}

int main()

{

unsigned int i=1;

cout << ::min(i,2) << endl;

}

Another simple example demonstrating that implicit conversion won't

Take place, the compiler will only instantiate exact matches.

It is advisable to put the implementation of all templates in the header file.

Class template

Class template allows us to introduce Generic user defined types. Just like Vector<T>.

template <class T>

class Calc {

public:

Calc(T a, T b): m_first(a), m_second(b) {}

T multiply() const { return m_first * m_second; }

T add() const { return m_first + m_second; }

private:

T m_first;

T m_second;

};Calc<int> mi(2.1, 3);

cout << mi.multiply() << endl;

Calc<double> md(2.1, 3);

cout << md.multiply() << endl;Instantiation type must incorporate the type.

Class template -constant & defaults

Just like function template class template can also have multiple generic types

template <class T, size_t SIZE = 8>

class Array {

public:

Array();

T& operator[](size_t index) { return m_data[index]; }

const T& operator[](size_t index) const { return m_data[index]; }

private:

T m_data[SIZE];

};

template <class T, size_t SIZE>

Array<T,SIZE>::Array()

{

for(size_t i=0; i < SIZE; ++i)

m_data[i] = 0;

}

The example above also demonstrates template constants as well as default values, types can also be defaulted.

Class template - specialisation

template <>

class Array<bool, 8> {

public:

Array(): m_data(0) {}

bool getBit(size_t index) const { return m_data & (1 << index); }

void setBit(size_t index) { m_data |= (1 << index); }

private:

unsigned char m_data;

};It is possible to specialise templates, in case a specific type requires special handling

It is possible to specialise templates, in case a specific type requires special handling.

Member function template

struct A {

template <class T> void foo(T i);

};

template <class T>

void A::foo(T i) { cout << "A<T>::foo(" << i << ")" << endl; }It may be useful to generalise some some internal class methods. Here is the syntax

A specialisation of a member function template can be done in only outside the class, and must be in the same file (usually header) where the class is defined.

template <>

void A::foo(double d) { cout << "A<double>::foo(" << d << ")" << endl; }Template Method in Template class

Somewhat more complex syntax

template <class T_CLASS>

struct A {

A(T_CLASS value):m_value(value) {}

template <class T_METHOD>

void foo(T_METHOD i);

public:

T_CLASS m_value;

};

template <class T_CLASS>

template <class T_METHOD>

void A<T_CLASS>::foo(T_METHOD i) { cout << "A<T>::foo(" << i << ")" << endl; }

template <>

template <>

void A<int>::foo(const char* d) { cout << "A<double>::foo(" << d << ")" << endl; }A member function specialisation of a member class requires the enclosing class to be also specialised.