Following the Trail of the

Henry Hayden Civil War Diary

from

Petersburg, Virginia, 1864 to Cedaredge, Colorado, 2014

Surface Creek Valley Historical Society

Cedaredge, Colorado

For Henry Hayden and Alexander Davidson

Phil Ellsworth, January 1, 2015

It is the one hundred fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Civil War. This story has its start in that war. It’s about a young soldier from Wisconsin, about a little diary he left behind, and about the improbable journey of the diary to Cedaredge, a little town in western Colorado.

I suppose this story has meant so much to me because I have had my own war, have lost comrades, and in my mind have been at their homes when the telegrams arrived; and I had two great-grandfathers in the Civil War, one of whom didn’t come home, whose burial place is unknown.

How did a little diary whose soldier died in battle one hundred and fifty years ago turn up in the office at Pioneer Town in Cedaredge? I have been working on that mystery off and on for sixteen years.

From time to time things of unknown origin appear in the office at Pioneer Town, the museum of the Surface Creek Valley Historical Society. Sometimes they are single objects, sometimes they are shoe boxes full of things, most often trivia.

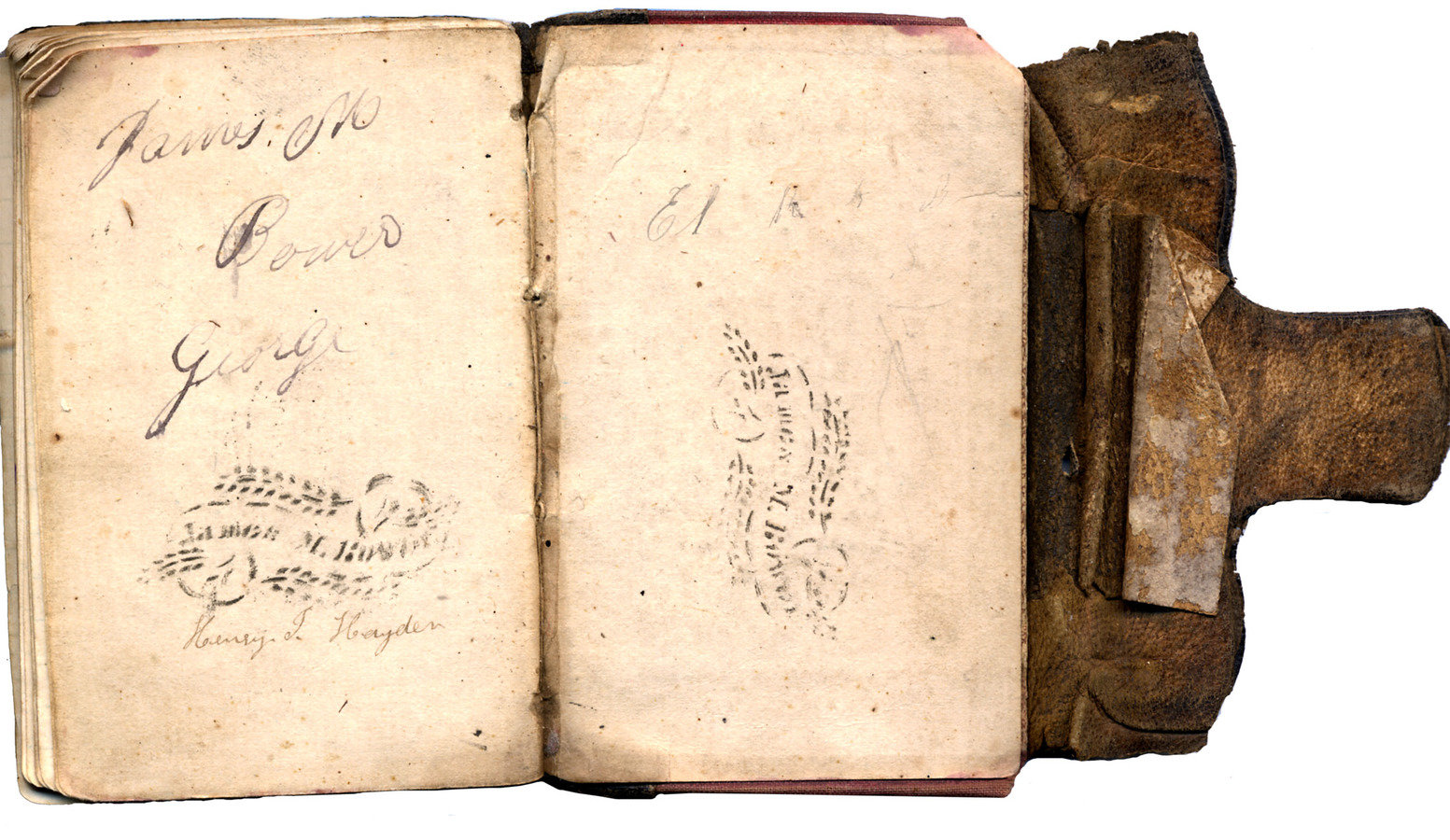

Once, and I have no recollection of the exact occasion, a little black book appeared.

It must have been in 1998 or before, because that’s when I first began trying to solve its mysteries. I have held it since 2009 as we have had no curator and I have been afraid of what might happen to it. Now we have a curator, Jane Everett, and I have turned it over to her.

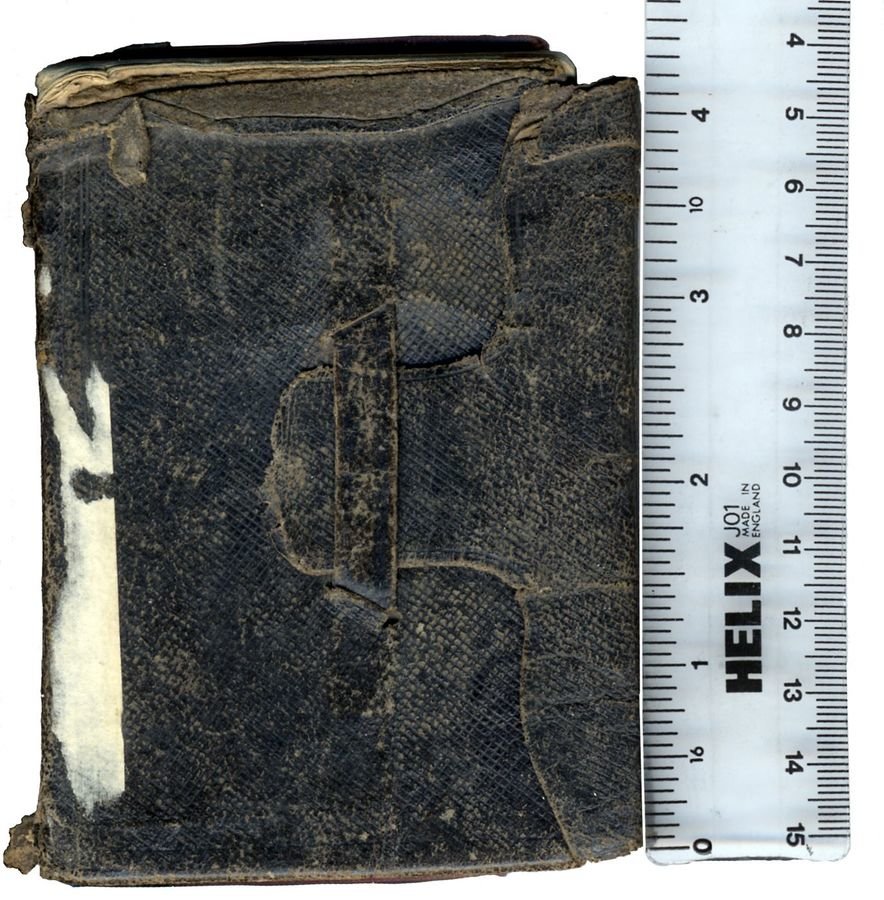

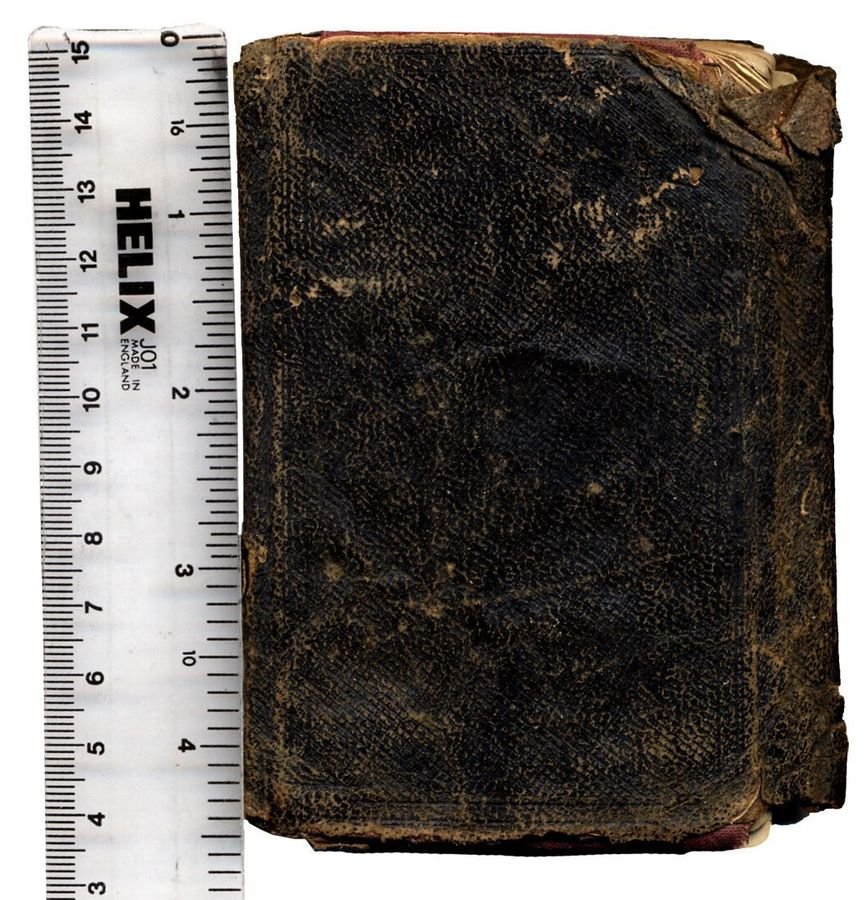

The book is really more like a wallet,

3" by 4",with a hundred pages.

Just seven of the pages are the diary of a young soldier who died in a charge at Petersburg, Virginia in 1864.

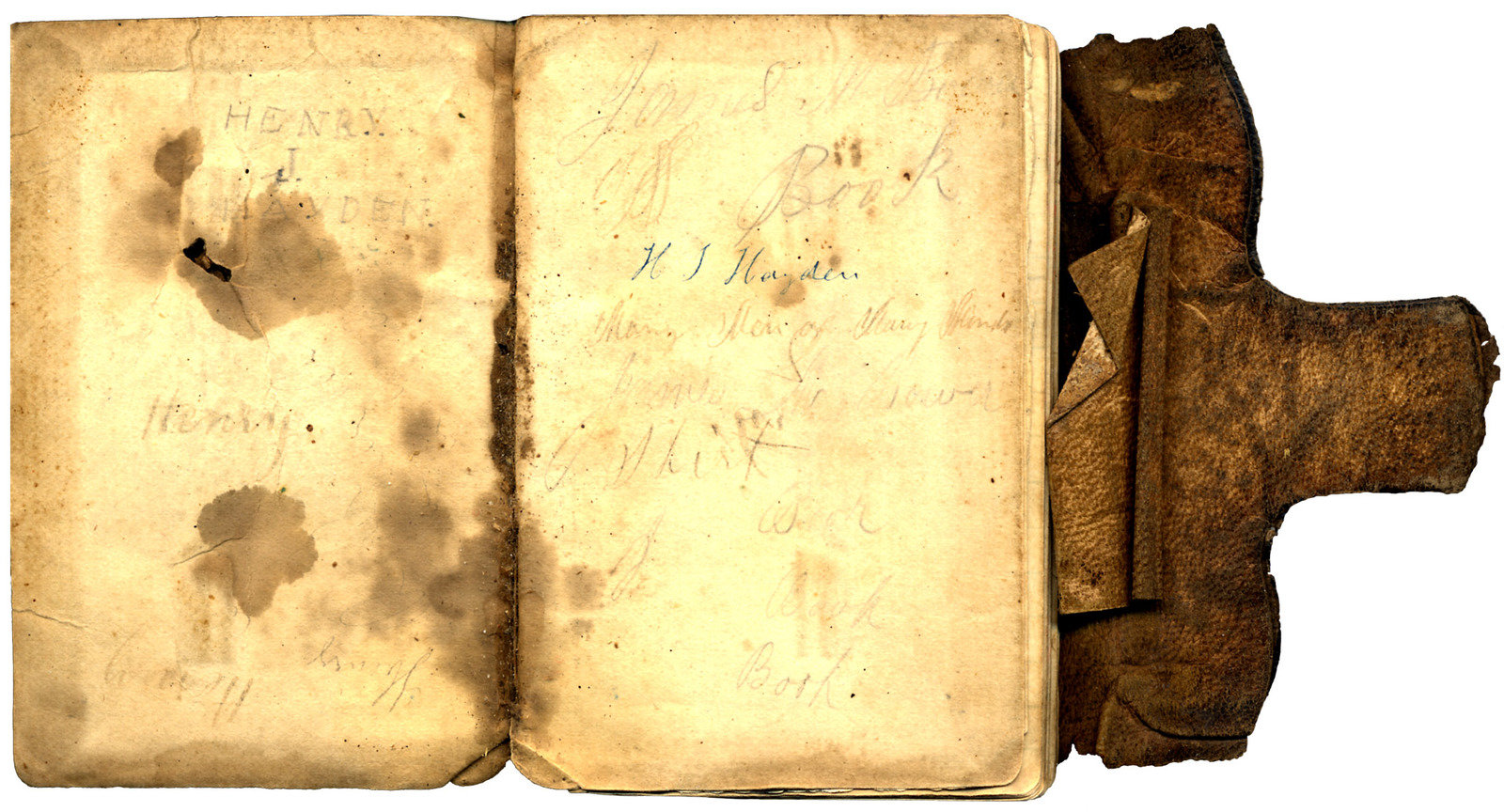

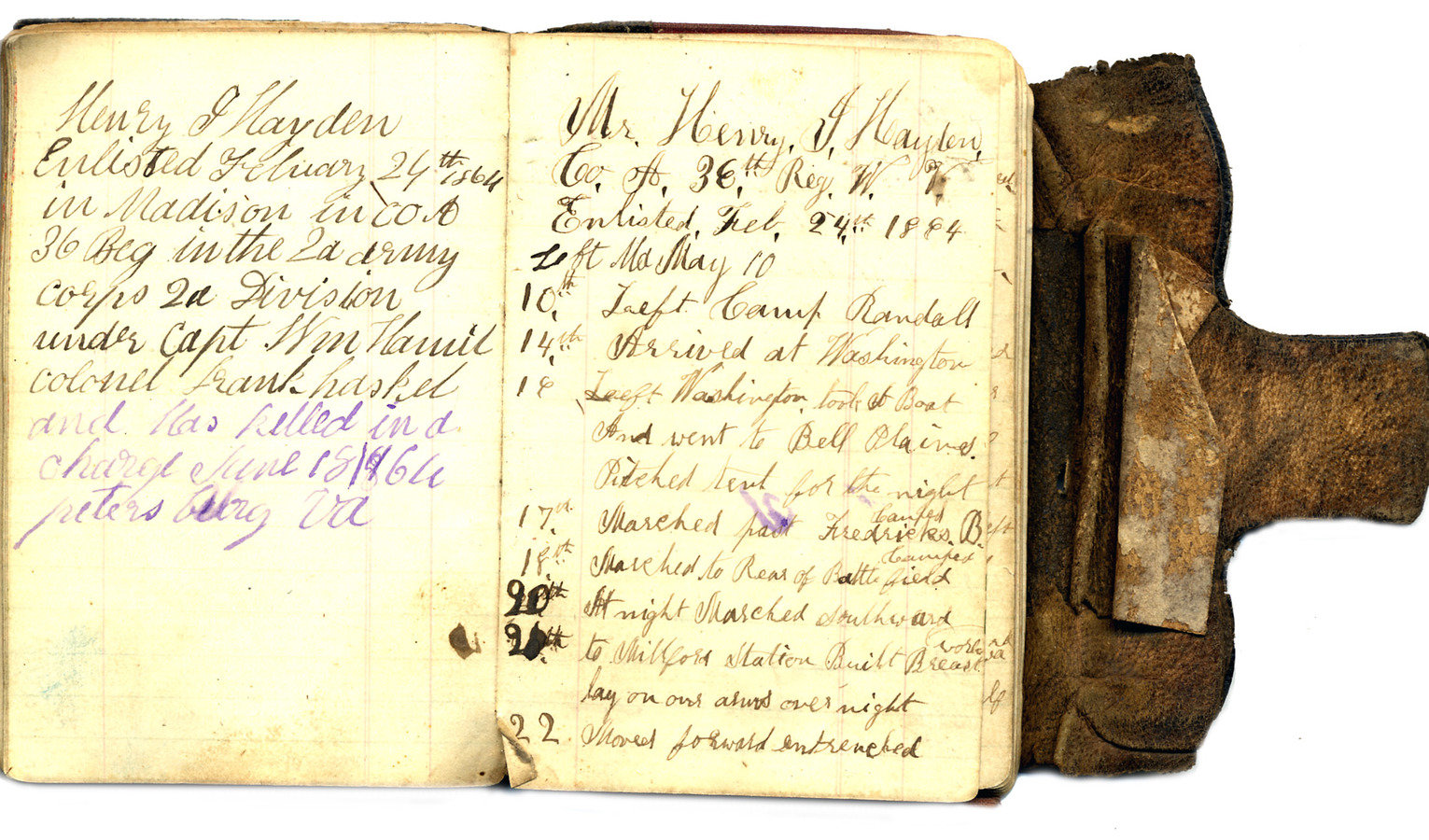

The soldier was Henry Hayden, and the diary says he enlisted February 24, 1864, in the 36th W.V. Regiment, and it mentions brothers Ashley and Lyman.

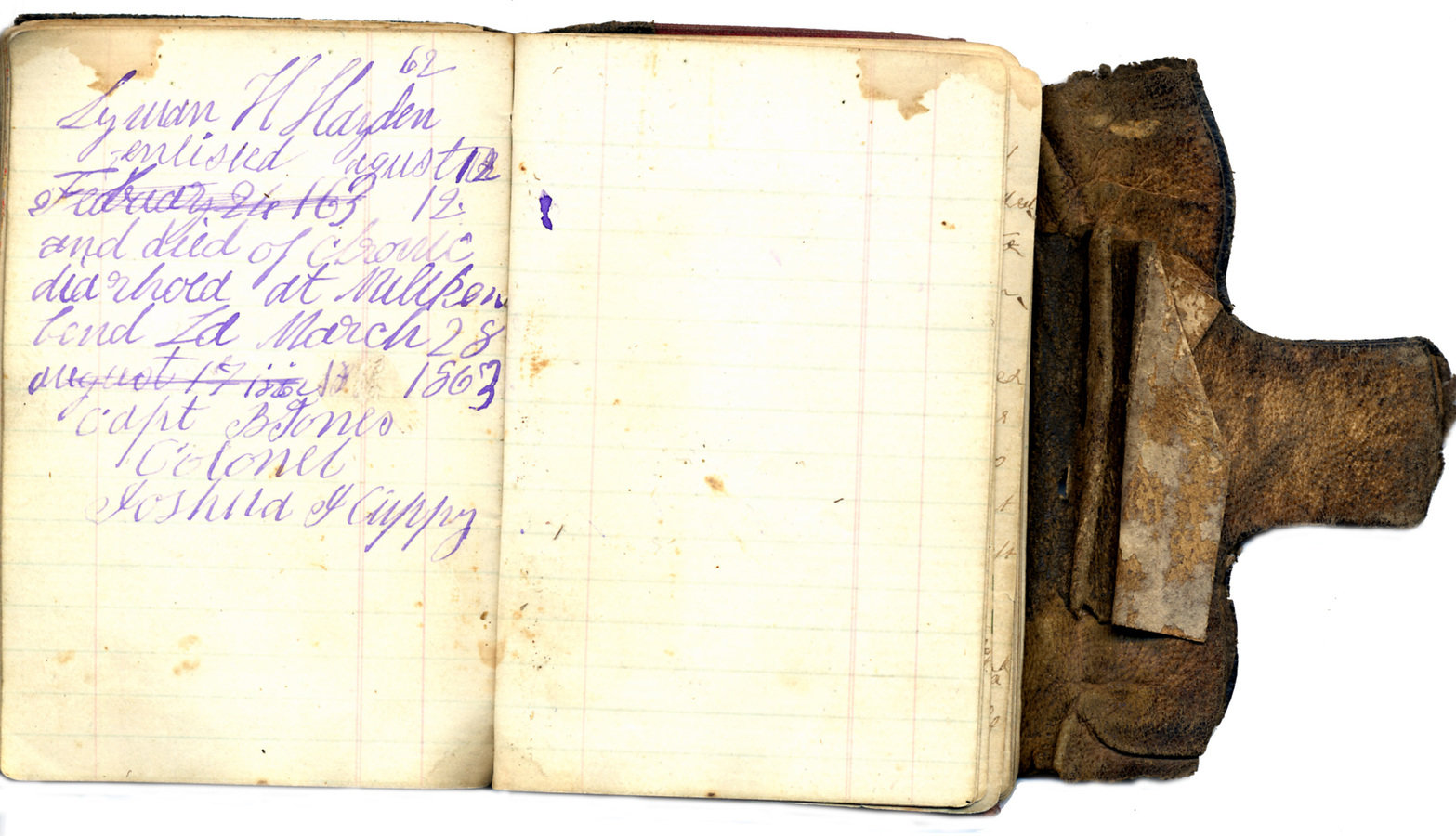

Lyman had died in the army at Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana, near Vicksburg.

The W.V. led to our first misstep. I took it to be West Virginia Regiment, but after finding no 36th West Virginia Regiment and searching among West Virginia Hayden families for those names the truth dawned and I saw that it was Wisconsin Volunteers.

With the names of the soldiers and knowing the state , a census search found them living in 1860 with their parents Horace and Lydia Hayden in Bear Creek, Sauk County, Wisconsin. Sauk County is the county of Aldo Leopold and Sand County Almanac. It is one of what he called the sand counties.

Henry and Ashley Hayden enlisted on February 24, 1864 in Company A, 36th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment. In January Stephen C. Foster had died in New York, and in March Beautiful Dreamer, his last song, was published.

Henry Hayden was nineteen and Ashley twenty-three.

The regiment was being raised by Colonel Frank Haskell, a veteran of Gettysburg and author of a classic account of that battle. Not much time was wasted in training. It was mustered in to Federal service in April, on May 10th left Wisconsin, and on the 16th arrived in Virginia. Can you imagine soldiers being sent to Normandy after less than three months training?

The Second Battle of the Wilderness was over with its nearly 28,000 casualties, and the Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse with its 30,000 was underway. It was there that on 18th of May the 36th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment caught up with the war.

Those battles and the succeeding battles, North Anna and Cold Harbor, the siege and capture of Petersburg, and the fall of Richmond resulted in more casualties than we suffered in Europe from the landing in Normandy in June 1944 until the following September.

Among them were Henry and Ashley Hayden. The diary covers only one month, from May 10 to June 10 , 1864. Hayden was killed on June 18, a month and eight days from home.

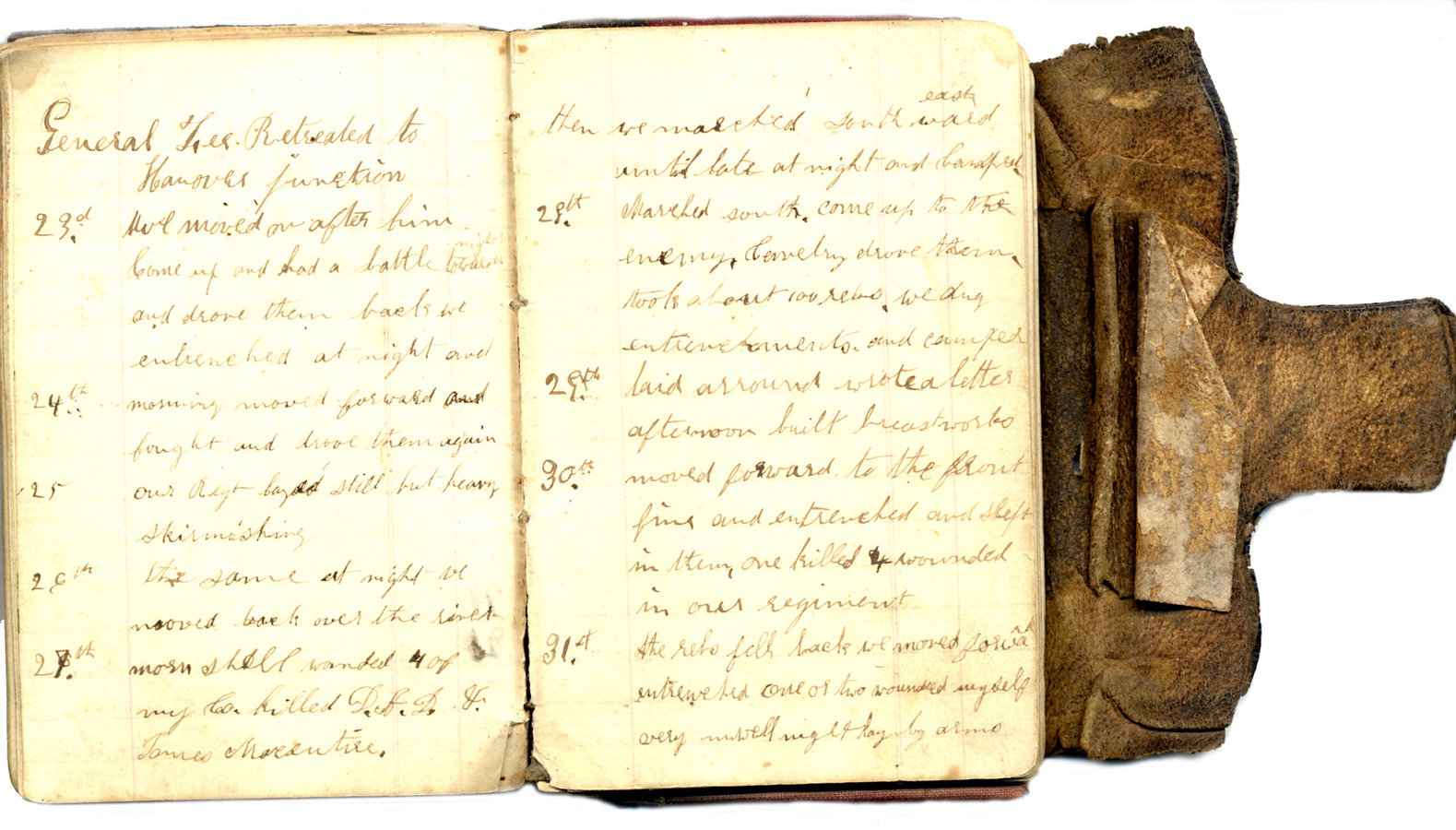

There are words in the diary that are illegible, but not many considering the conditions under which an infantry soldier lives. Only the seven pages describing Army service days have been transcribed.

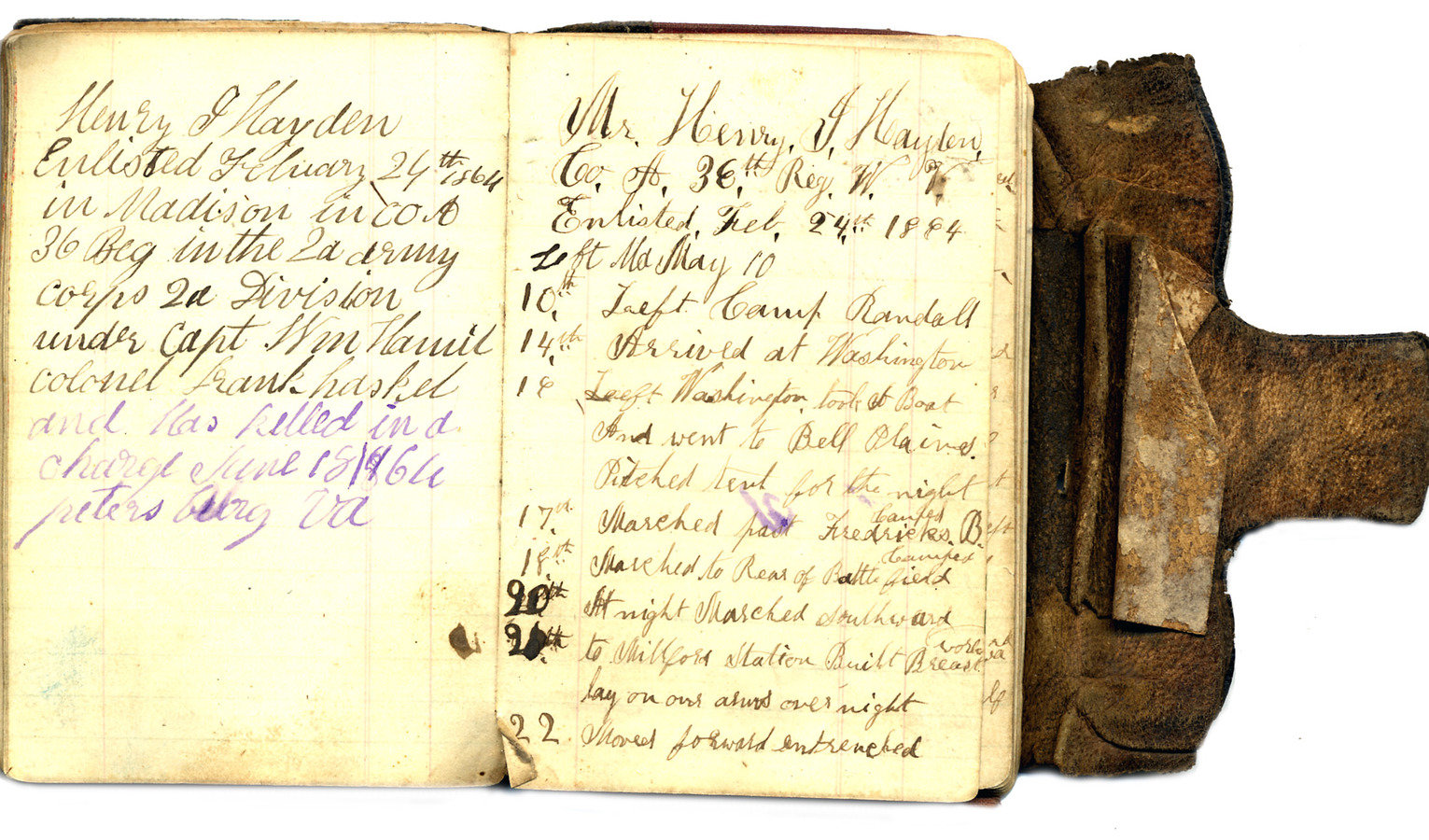

Mr. Henry Hayden

Co. A, 36th Reg. W.V.

Enlisted Feb. 24th, 1864

- Left Ma (?) May 10 (Ma probably indicates Madison)

- 10th Left Camp Randall(Camp Randall is in Madison, Wisconsin)

- 14th Arrived at Washington

- 16 Left Washington took a boat

- And went to Bell Plains (a steamboat landing supply port in northern Virginia)

- Pitched tent for the night

- 17th Marched past Fredericksburg camped

- 18th Marched to rear of battlefield camped

- 20th At night marched southward

- 21st To Millford Station Built breastwork Lay on ? overnight

- 22. Moved forward entrenched

- General Lee retreated to Hanover Junction

- 23rd We moved after him Come up and had a battle (?) and drove them back we entrenched at night and

- 24th morning moved forward and Fought and drove them again

- 25 Our regiment layed still but heavy skirmishing

- 26th The same at night we moved back over the field

- 27th morn shell wounded 4 of my co. Killed Lieut (?) - - James MacIntire

Then we marched northeastward

until late at night and camped

- 28th Marched south, come up to the Enemy cavalry drove them Took about 100 rebs, we dug entrenchments, and camped

- 29th laid around wrote a letter afternoon built breastworks

- 30th moved forward to the front

line and entrenched and slept

in them, one killed 4 wounded in our regiment - 31st the rebs fell back we moved forward

entrenched one or two wounded myself

Very unwell night lay by alone

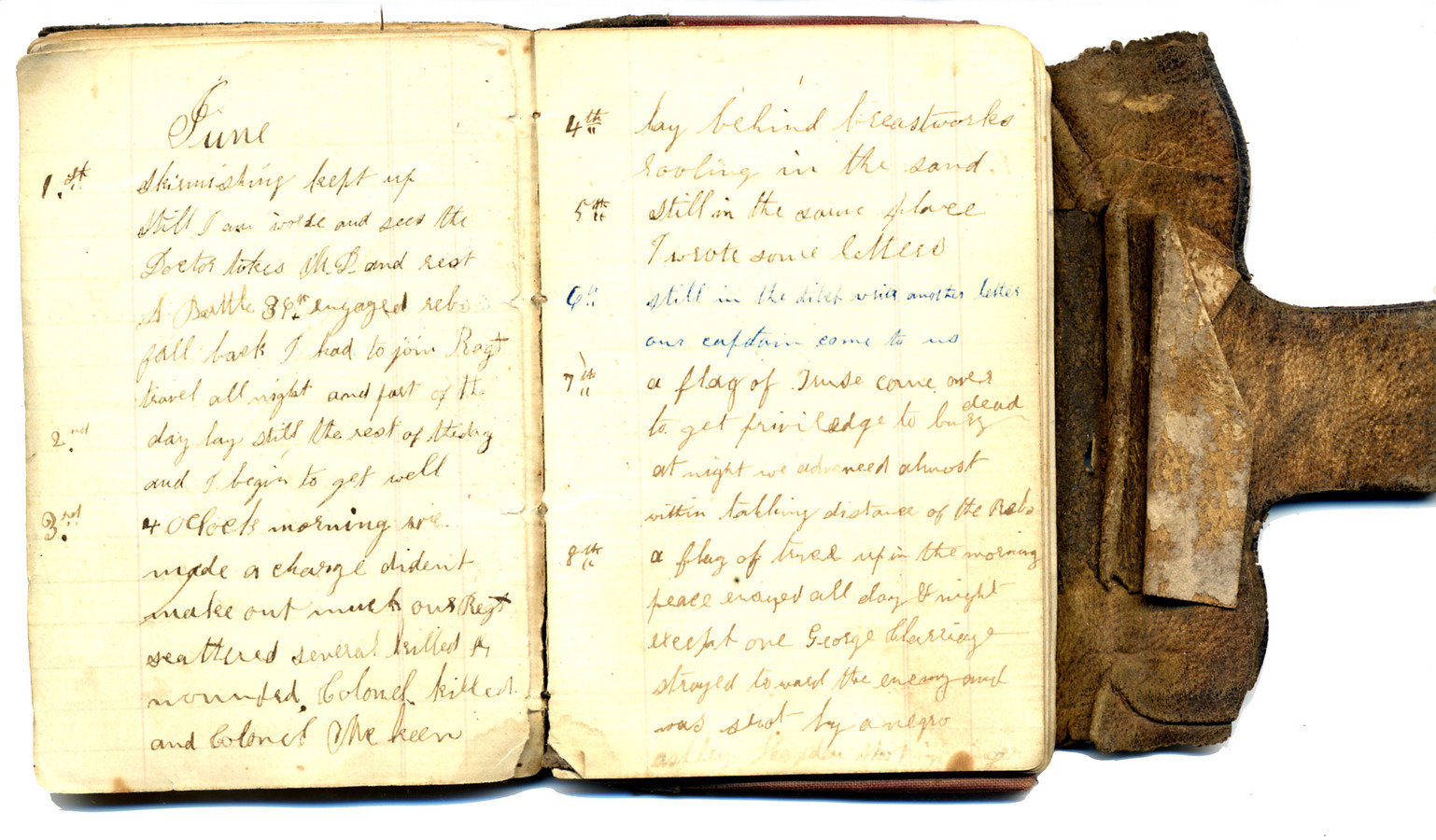

- June 1st Skirmishes kept up

Still I am unwell and see the

Doctor ? and rest

A battle 36th engaged rebs

fall back I had to join Regt

travel all night and part of the - 2nd day lay still the rest of the day

and begin to get well

- 3rd 4 o’clock morning

made a charge dident

make out much our Regt

scattered several killed and

wounded Colonel killed (this was Colonel Haskell, who raised the regiment)

and Colonel McKeen

- 4th lay behind breastworks

fooling? in the sand - 5th Still in the same place

I wrote some letters - 6th still in the ditch write another letter

and captain comes to us

- 7th a flag of truce came out

to get priviledge to bury dead

at night we advanced almost

within talking distance of the Rebs

- 8th a flag of truce up in the morning

peace all day and night

except one George Claridge

strayed toward the enemy and

was shot by a negro

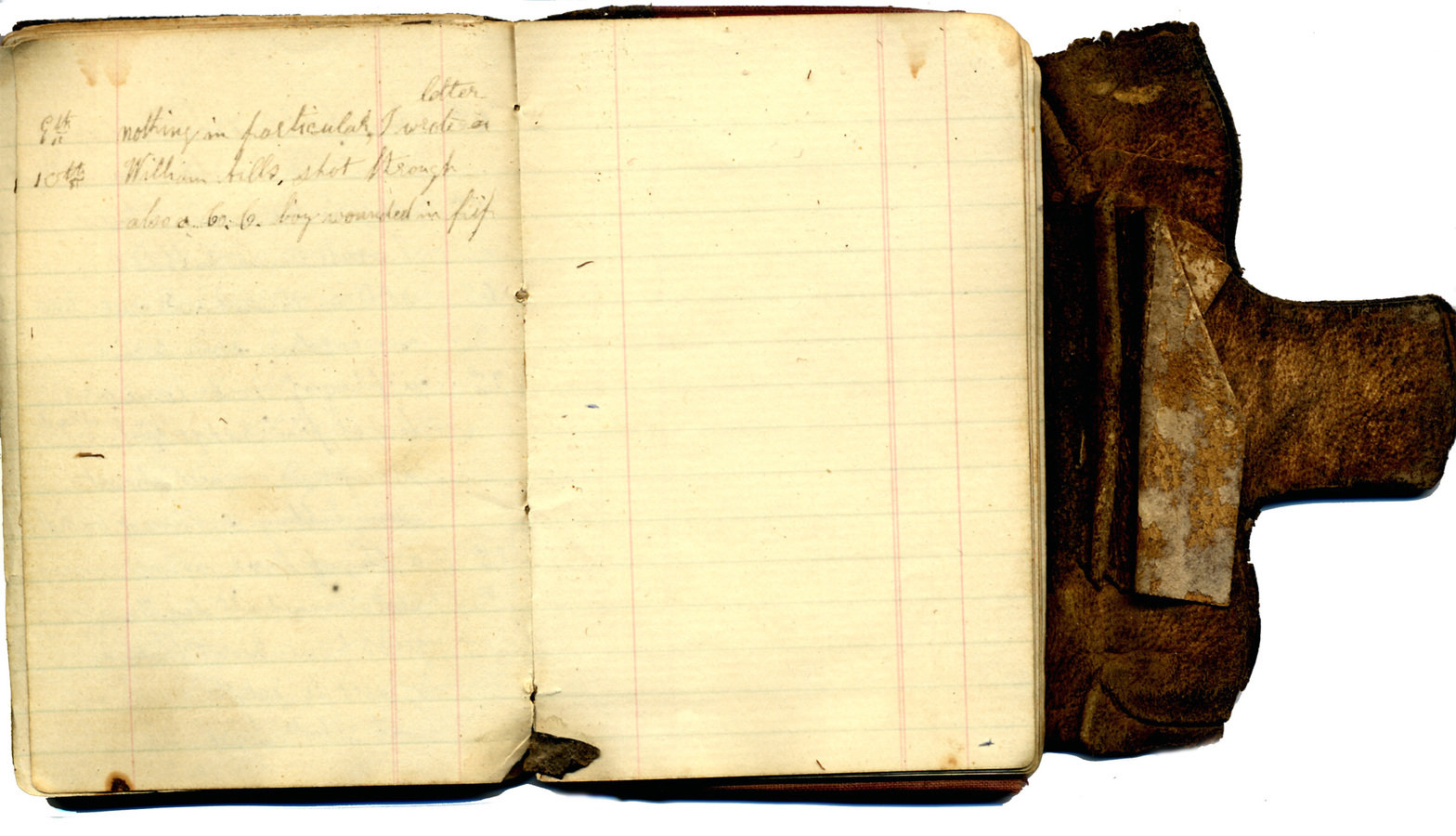

- 9th nothing in particular. I wrote a letter

- 10th William Bills, shot (illegible)

also a Co. G. boy wounded in (illegible)

- The diary ends there, on June 10th.

From about May 31 to June 10 most of the entries must have been written at Cold Harbor, and the end of the diary on June 10th coincides with the movement of the army from Cold Harbor to Petersburg.

In his memoir General Grant said, “ I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made. At Cold Harbor no advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained. (13,000 Union killed and wounded)”.

This was June 3rd, on which day Hayden noted “4 o’clock morning made a charge dident make out much our Regt scattered several killed and wounded Colonel killed and Colonel McKeen”. (Henry Boyd McKeen). The unnamed colonel was Colonel Frank Haskell, the one who had raised the 36th Regiment.

On the page preceding the actual diary in what appears to be Hayden’s handwriting are the words: “Henry J. Hayden enlisted February 24, 1864 in Madison in Co. A. in the 2nd Army Corps 2d Division under Capt Wm Hamill (Hamilton) Colonel Frank Haskel” and then in different handwriting and different ink: “and was killed in a charge June 18 1864 Petersburg, VA.”

When I read that entry I think of the family at home on the farm in Sauk County and of Walt Whitman’s poem “Come Up from the Fields Father”, a poem about a letter that has come with word that their son has been fatally wounded; and I think of my great-grandmother, Caroline Davidson, on a farm in Macoupin County, Illinois, receiving such a letter about her husband. My grandfather was three years old at the time.

The charge in which Henry Hayden lost his life is recounted in a history of the 36th Regiment by James M. Aubery, who participated in it. It begins with the order from General Meade, Commander of the Army of the Potomac.

Headquarters Army of Potomac, June 17th, 11 p. m [circular.] A vigorous assault on the enemy's works will be made to-morrow morning at 4 o'clock by the whole force of the Fifth, Ninth and Second Corps • * • and the general commanding hopes by a united and vigorous effort to drive the enemy beyond the Appomattox. By command of Major-General Meade.

The above circular of General Meade, issued at 11 p. m. on the 17th, came to us through the regular channel. The regiment was formed in line of battle at 4 a. m. the next day (18th), they advanced driving the enemy's skirmish line from heavy works, and followed them about a mile through a dense wood, in front of which, across an open field, lay the main rebel line, strongly entrenched. While advancing through the woods. Lieutenant Galloway of Company K fell mortally wounded. At 2 in the afternoon a general advance was ordered.

Colonel Savage, who commanded the regiment, stopped in front of the colors, shouting: "Three cheers for the honor of Wisconsin; forward, my brave men !" at the same time springing over the slight works behind which the regiment was lying. The regiment advanced, but the effort was vain. Within two minutes Colonel Savage fell mortally wounded; Major Brown received two severe wounds; Lieutenants Harris and Morris were severely wounded and nearly one- third of the men fell killed or wounded.

The regiment halted, looked to the right and to the left and found it was the only one which had advanced over the works. It was certain death to advance and no less dangerous to retreat. The soil being light and sandy, the men lay down, burrowing with their cups and plates to make any protection possible.

Here they had to remain under fire until dark, when they retreated the best they could. This charge is known in the regiment as the "'charge over the melon patch." Captain Fisk of Company C was the last man to leave the field, bringing with him the dead and wounded. Captain Warner of Company B, being the senior officer, the command of the regiment devolved on him.

The loss during the day was five officers and one hundred and eleven (men) killed and wounded. The night was spent in burying the dead and caring for the wounded. There was heavy cannonading and musketry' all night.

Aubery then names the killed and wounded by company beginning with the killed.

On the list the first is:

Company A Henry J. Hayden

Who saved the diary from the carnage? In a number of places in the book is stamped or written the name James M. Bower (B-o-w-e-r). For a while we thought Bower might have been someone with Surface Creek connections and we looked for B-o-w-er or B-a-u-e-r connections here. Then we found that he was a corporal in Hayden’s company and was from Bear Creek, Hayden’s home town.

p. 100 and inside back cover

What of Hayden’s brother Ashley, who served in the same company? The regimental roster reports him to have been wounded at Cold Harbor, though the diary says nothing of that; but because of the wound he probably wasn’t at Petersburg. It is my guess that Bower recovered the diary and gave it to Hayden’s parents after the war. But how did it get to Cedaredge?

The break came when it was found that the soldier’s brother Ashley had died in Fruita, Colorado, just seventy miles from Cedaredge. I had posted an on-line query in 1998 and another in 1999 seeking information about Henry, Ashley, and Lyman but received no responses. Then in 2007 I found a 1999 posting by Gene Myers of Lindale, Texas with the family of Horace and Lydia Hayden.

The family included among the children Houghton Ashley, Huron Lyman, and Henry Joshua. No places or dates of death were given for Lyman or Henry, but Ashley, their brother, is shown as dying in Fruita in 1909. It shows that the family had lived in Missouri before Ashley moved to Fruita and that the father had died there. Census records show that the move to Fruita was after 1900.

Since he died in 1909 he doesn’t appear on any Federal census there and it is only the Myers posting that connected him to Fruita. One can imagine the diary having been in the possession of Hayden’s parents and then having been left to Ashley Hayden, to go with him to Fruita. But Myers didn’t know of a Cedaredge connection. How did the diary get to Cedaredge?

It is here that the power of search engines and genealogical data bases shows. From information on Ancestry.com we have the surnames of some of the grandchildren of Ashley Hayden. Those we have are Hayden, Morse, Myers, Boyd, Smith, and Green. Boyd is a name with Pioneer Town connections.

I recall, or think I recall, a “shoebox” having been dropped off at Pioneer Town by someone from the Boyd family who lived near the old States coal mine near the intersection of T and Green Valley roads. One step-grandson of Ashley Hayden was a Clarence Boyd, and the 1940 Federal census shows a Clarence Boyd, coal miner, Cedaredge.

Genealogical search has shown that Clarence Boyd, the coal miner at Cedaredge, was indeed a step-grandson of Ashley Hayden. Not only that, but he married a granddaughter of Ashley Hayden, Florence Lynn Smith. She is on the 1940 Cedaredge census (Florence Boyd). So that places a grand-niece of Henry Hayden, the soldier, in Cedaredge. Surely she must have been the one who brought the diary here. We can’t ask her for she died in Washington state in 2010.

The Boyd connection to Pioneer Town goes beyond the hazy recollection of a shoebox having been dropped off. William Boyd, who lives near the old States Mine at the present time, has told me that Clarence Boyd was his great-uncle. William’s grandfather was Walter B. Boyd, Clarence’s brother, and his grandmother was Genevieve States, whose father was owner of the mine and whose museum became an integral part of Pioneer Town.

Perhaps Florence Smith Boyd gave the diary to Charles States and it has become separated at Pioneer Town from the other parts of his collection. It may be that further inquiry among the Boyds will answer the question.

In retrospect, it is the World Wide Web, only in operation since the mid-nineties, that has made following the diary’s trail possible. Without it, it would have been impossible to discover the Fruita connection or a connection between Fruita and a coal mine in Cedaredge.

It would have been impossible for us to discover that Florence Lynn Boyd, of Cedaredge, was a grand-niece of Henry Hayden, a young Wisconsin soldier who died in a charge at Petersburg a hundred and fifty-one years ago. In fact, nearly every step in the search would have been impossible twenty years ago, and some probably impossible as recently as two or three years ago.

After the war in an effort to gather all the Union dead from Petersburg and surrounding areas to one place, Poplar Grove National Cemetery was established, just south of the city. A search found 6,718 remains, of which only 2, 139 were identified. In Blandford Cemetery in Petersburg there are the graves of almost 30,000 Confederate soldiers. Only 2,000 are identified.

Henry Hayden is one of those whose resting place is unknown. He could be one of the unidentified at Poplar Grove. He has no great-grandchildren to remember him. There is only the little diary that found its way to us.

In the evening when the sound of taps drifts across our little town, remember him.

...