Functional JavaScript

Rob Hilgefort

> whoami

Background

- Rob Hilgefort

- Cincinnati, OH native

- University of Kentucky graduate

- Moved to Denver, CO in 2018

- 10 years professional JS experience

Contact

- : rjhilgefort

- : rjhilgefort

- : rob.hilgefort.me

This Is

- A Zero FP knowledge talk

- Enablement to read/write FP in the real world

This Is Not

- An intro to JS

- A deep dive into FP

- ADT Coverage

- A Hindley Milner Notation Intro (probably)

At A Glance

(let's look at some code)

Imperative Approach

const users = [

{ active: true, first: 'Rob ', last: ' Hilgefort ' }, // 12

{ active: true, first: 'John ', last: ' Doe' }, // 7

{ active: false, first: ' Jane', last: 'Smith ' }, // 9

{ active: true, first: 'Jesselin ', last: ' Alexandra ' }, // 17

]

const sumNameLengths = (users) => {

let filteredUsers = []

for (let i = 0; i < users.length; i++) {

const user = users[i]

if (user.active) {

filteredUsers.push(user)

}

}

let allLengths = 0

for (let i = 0; i < filteredUsers.length; i++) {

const user = filteredUsers[i]

allLengths += user.first.trim().length + user.last.trim().length

}

return allLengths

}

sumNameLengths(users) // 36Problems With Imperative

const users = [

{ active: true, first: 'Rob ', last: ' Hilgefort ' }, // 12

{ active: true, first: 'John ', last: ' Doe' }, // 7

{ active: false, first: ' Jane', last: 'Smith ' }, // 9

{ active: true, first: 'Jesselin ', last: ' Alexandra ' }, // 17

]

const sumNameLengths = (users) => {

let filteredUsers = [] // intermediate state

for (let i = 0; i < users.length; i++) { // Duplicate structure traversal code

const user = users[i] // intermediate state

if (user.active) {

filteredUsers.push(user)

}

}

let allLengths = 0

for (let i = 0; i < filteredUsers.length; i++) { // Duplicate structure traversal code

const user = filteredUsers[i] // easy to make a mistake here and reference `users`

// hard to see what the math is we're even doing

allLengths += user.first.trim().length + user.last.trim().length

}

return allLengths // Other variables don't matter and are just intermediate state

}

sumNameLengths(users)Declarative / FP

import { pipe, filter, map, pipe, pick, trim, length, values, sum } from 'ramda'

const users = [

{ active: true, first: 'Rob ', last: ' Hilgefort ' }, // 12

{ active: true, first: 'John ', last: ' Doe' }, // 7

{ active: false, first: ' Jane', last: 'Smith ' }, // 9

{ active: true, first: 'Jesselin ', last: ' Alexandra ' }, // 17

]

// User :: { active: Bool, first: String, last: String }

// sumNameLength :: [User] -> Number

const sumNameLength = pipe(

filter(propEq('active', true)),

map(pipe(

pick(['first', 'last']),

map(pipe(trim, length)),

values,

sum,

)),

sum,

)

sumNameLength(users) // 36

Is that even JavaScript?

WAT

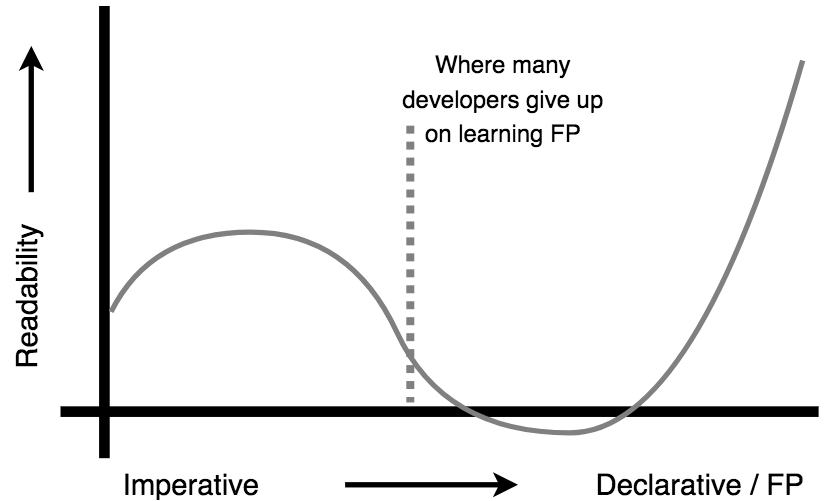

Learning Curve

Functional Programming

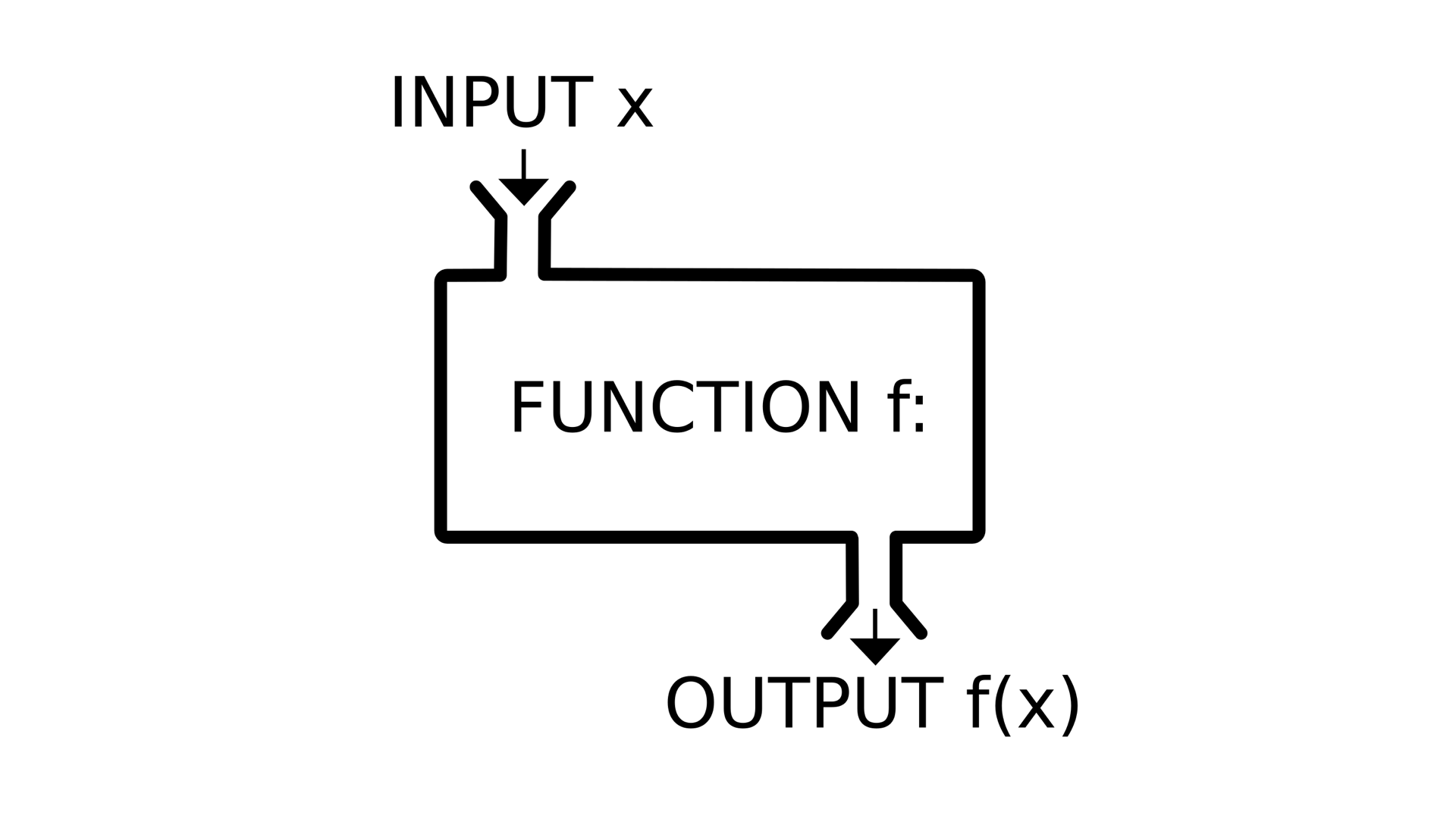

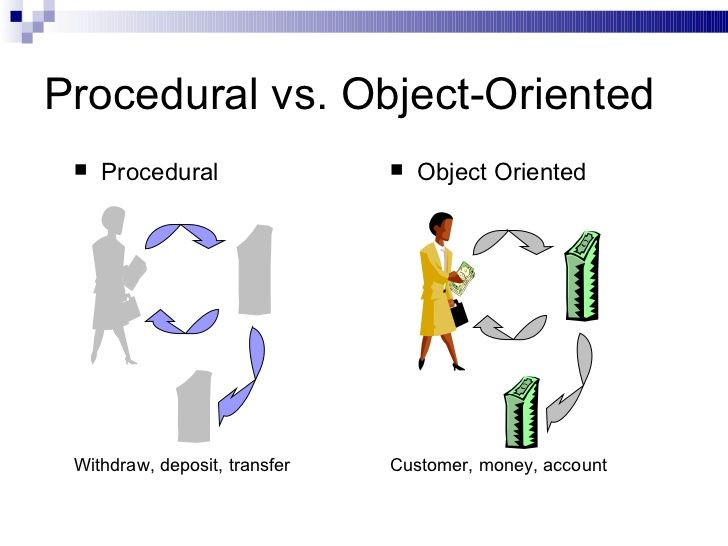

Functional programming (FP) is a programming paradigm that is the process of building software by composing pure functions and avoiding shared state, mutable data, and side-effects.

Data passes through transformations.

vs Object Oriented Programming

This is different than Object oriented programming (OOP), where application state is usually shared and colocated with methods in objects.

Why Functional Programming?

Problems With Imperative

| Error Prone | It's much easier to make mistakes when you have more code and more variables to keep track of |

| Hard To Refactor | The math we were doing was coupled with the structure traversal |

| Mutations | Easy to have unexpected side effects happen when mutating state |

| Noise | The data being acted on is buried in code that is extraneous |

| !Single Responsibility Principle: | Operations/Logic are coupled and harder to reuse |

FP Advantages

| Predictability | Pure functions mean we always get the same output for a given input |

| Testability | Pure functions are easy to test because you don't have to mock |

| Easy To Reason About | Declarative code indicates intent and desire, self documenting |

| Single Responsibility Principle | FP encourages tiny composable methods (lego blocks) which are easy to reuse |

| Refactorability | Tiny composable methods are easy to move around and/or remove |

How?

1️⃣ Tools

- Higher Order Functions

- Currying

- Composition

2️⃣ Rules

- Purity

- Immutability

- No Side Effects

3️⃣ Concepts

- Declarative

- First Class Functions

- Point Free

FP Topics

Don't Worry!

We'll cover these, look for this icon!

Let's Break This Down

import { pipe, filter, map, pipe, pick, trim, length, values, sum } from 'ramda'

const users = [

{ active: true, first: 'Rob ', last: ' Hilgefort ' }, // 12

{ active: true, first: 'John ', last: ' Doe' }, // 7

{ active: false, first: ' Jane', last: 'Smith ' }, // 9

{ active: true, first: 'Jesselin ', last: ' Alexandra ' }, // 17

]

// User :: { active: Bool, first: String, last: String }

// sumNameLength :: [User] -> Number

const sumNameLength = pipe(

filter(propEq('active', true)),

map(pipe(

pick(['first', 'last']),

map(pipe(trim, length)),

values,

sum,

)),

sum,

)

sumNameLength(users) // 36

Filtering The Users

import { pipe, filter, map, pipe, pick, trim, length, values, sum } from 'ramda'

const users = [

{ active: true, first: 'Rob ', last: ' Hilgefort ' }, // 12

{ active: true, first: 'John ', last: ' Doe' }, // 7

{ active: false, first: ' Jane', last: 'Smith ' }, // 9

{ active: true, first: 'Jesselin ', last: ' Alexandra ' }, // 17

]

// User :: { active: Bool, first: String, last: String }

// sumNameLength :: [User] -> Number

const sumNameLength = pipe(

filter(

propEq('active', true)

),

map(pipe(

pick(['first', 'last']),

map(

pipe(trim, length)

),

values,

sum,

)),

sum,

)

sumNameLength(users) // 36In `sumNameLength`, we first need to select only the active users from the list. We need to filter the list.

Imperative Filter

const sumNameLengths = (users) => {

let filteredUsers = []

for (let i = 0; i < users.length; i++) {

const user = users[i]

if (user.active) {

filteredUsers.push(user)

}

}

let allLengths = 0

for (let i = 0; i < filteredUsers.length; i++) {

const user = filteredUsers[i]

allLengths += user.first.trim().length + user.last.trim().length

}

return allLengths

}In our imperative approach, we described how to filter, and we tightly coupled our array traversal with our "predicate" (condition).

Furthermore, our function has to be concerned with how to traverse an array. Ideally, it would just say what it wants to filter on, and not be concerned with how.

Single Responsibility Principle

// filter ::

// ((* -> Boolean), Array a)

// -> Array b

const filter = (predicate, data) => {

let filtered = []

for (let i = 0; i < data.length; i++) {

const val = data[i]

if (predicate(val)) {

filtered.push(val)

}

}

return filtered

}

// isLessThan5 :: Number -> Boolean

const isLessThan5 = x => x < 5

filter(isLessThan5, [1, 3, 6, 8])

// -> [1, 3]Let's hide all the details of how to traverse a list and filter by a predicate.

This allows us to reuse this functionality and allow the callers to say what they want, and not be concerned with how to do it.

FP Topics

1️⃣ Tools

- Higher Order Functions

- Currying

- Composition

2️⃣ Rules

- Purity

- Immutability

- No Side Effects

3️⃣ Concepts

- Declarative

- First Class Functions

- Point Free

Declarative Programming

// Imperative

// Double every number in list

const nums = [2, 5, 8];

for (let i = 0; i < nums.length; i++) {

nums[i] = nums[i] * 2

}

nums // [4, 10, 16]Express the logic of a computation without describing its control flow.

Programming is done with expressions or declarations instead of statements. In contrast, imperative programming uses statements that change a program's state.

// Declarative

// Double every number in list

const double = x => x * 2

const nums = [2, 5, 8];

const numsDoubled = nums.map(double)

numsDoubled // [4, 10, 16]

First Class Functions

Functions are values.

First class function support means we can treat functions like any other data type and there is nothing particularly special about them - they may be stored in arrays, passed around as function parameters, assigned to variables, etc.

// isLessThan5 :: Number -> Boolean

const isLessThan5 = x => x < 5

filter(

isLessThan5,

[1, 3, 6, 8]

)

// -> [1, 3]

Higher Order Functions

Functions take and can return functions.

First class function support enables higher order functions- functions that work on other functions, meaning that they take one or more functions as an argument and can also return a function.

const getServerStuff = (callback) => {

return ajaxCall((json) => {

return callback(json)

})

}

// ... is the same as ...

const getServerStuff = ajaxCall;

Higher Order Functions

const getServerStuff = (callback) => {

return ajaxCall((json) => {

return callback(json)

})

}const getServerStuff = (callback) => {

return ajaxCall(callback)

}const getServerStuff = ajaxCall

Okay, back to the breakdown!

Filtering For Active Users

import { pipe, filter, map, pipe, pick, trim, length, values, sum } from 'ramda'

const users = [

{ active: true, first: 'Rob ', last: ' Hilgefort ' }, // 12

{ active: true, first: 'John ', last: ' Doe' }, // 7

{ active: false, first: ' Jane', last: 'Smith ' }, // 9

{ active: true, first: 'Jesselin ', last: ' Alexandra ' }, // 17

]

// User :: { active: Bool, first: String, last: String }

// sumNameLength :: [User] -> Number

const sumNameLength = pipe(

filter(

propEq('active', true)

),

map(pipe(

pick(['first', 'last']),

map(

pipe(trim, length)

),

values,

sum,

)),

sum,

)

sumNameLength(users) // 36We've created an abstraction for `filter`, let's look at the predicate (condition) we're passing to it to select only the users which have a prop `active` equal to `true`.

Let's try write our own version of this function which is looking to find a property which equals a value.

`propEq` Predicate

filter(

(user) => user.active === true,

users

)

const isUserActive =

(user) => user.active === true

filter(

user => isUserActive(user),

users

)

const isActive =

(data) => data.active === true

filter(

user => isActive(user),

users

)

const isPropTrue =

(prop, data) => data[prop] === true

filter(

user => isPropTrue('active', user),

users

)

const propEq =

(prop, val, data) => data[prop] === val

filter(

user => propEq('active', true, user),

users

)Works, but not reusable

We can name it, but it could apply to more than users

Nice, but we could be flexible to other props

While we're at it, we may as well make it fully flexible/reusable

✅, but we've learned that passing data through is noisy...

// User :: { active: Bool, first: String, last: String }

// sumNameLength :: [User] -> Number

const sumNameLength = pipe(

filter(

propEq('active', true)

),

map(pipe(

pick(['first', 'last']),

map(

pipe(trim, length)

),

values,

sum,

)),

sum,

)What can we do to `propEq` to make this possible?

const propEq =

(prop, val, data) => data[prop] === valconst getServerStuff = (callback) => {

return ajaxCall((json) => {

return callback(json)

})

}

// ... is the same as ...

const getServerStuff = ajaxCall;Can we apply this HOC principle to reduce code and not name the data we're acting on?

So what's going on here?

`propEq` Predicate

// propEq ::

// (String, Any) -> Object -> Boolean

const propEq = (prop, val) => data =>

data[prop] === valWe can build our function to return a function after providing the first two arguments.

`propEq` Predicate

Now we can provide the information we care about, and let `filter` fill in the rest.

// User :: { active: Bool, first: String, last: String }

// sumNameLength :: [User] -> Number

const sumNameLength = pipe(

filter(

propEq('active', true)

),

map(pipe(

pick(['first', 'last']),

map(

pipe(trim, length)

),

values,

sum,

)),

sum,

)FP Topics

1️⃣ Tools

- Higher Order Functions

- Currying

- Composition

2️⃣ Rules

- Purity

- Immutability

- No Side Effects

3️⃣ Concepts

- Declarative

- First Class Functions

- Point Free

const double = (x) => x * 2

[1,2,3,4,5].map(

(number) => double(number)

)

// [2,4,6,8,10]

// ... is the same as ...

const double = (x) => x * 2

[1,2,3,4,5].map(double)

// [2,4,6,8,10]No intermediate state.

Pointfree style means never having to say your data. Functions never mention the data upon which they operate.

Pointfree code can help us remove needless names and keep us concise and generic.

Point Free

What about non unary functions like our `propEq` function?

(Function arity refers to the number of arguments a function takes)

Non Unary Function

// propEq ::

// (String, Any) -> Object -> Boolean

const propEq = (prop, val) => data =>

data[prop] === valconst add = x => y => z =>

x + y + z

add(1)(2)(3) // 6

add(1, 2, 3) // <Function>

Manual Currying refers to function interfaces that expect their arguments one at a time.

You can call a function with fewer arguments than it expects. It returns a function that takes the remaining arguments. Because of this, it is critical that your data be supplied as the final argument.

Manual Currying

When we left our third argument out, to be filled in later, we curried our function!

import { curry } from 'ramda'

const add = curry(

(x, y, z) => x + y + z

)

add(1, 2, 3) // 6

add(1)(2)(3) // 6

add(1, 2)(3) // 6

add(1)(2, 3) // 6

Many functional libraries provide a `curry` function which allow functions to be called like a normal function if desired. This is called Auto Currying.

When called with fewer than the expected arguments, a function is returned waiting for the remaining arguments.

Auto Currying

const add = x => y => z =>

x + y + z

const add12 = add(10)(2)

add12(1) // 13

add12(8) // 20

add12(12) // 24Back To The Breakdown

import { pipe, filter, map, pipe, pick, trim, length, values, sum } from 'ramda'

const users = [

{ active: true, first: 'Rob ', last: ' Hilgefort ' }, // 12

{ active: true, first: 'John ', last: ' Doe' }, // 7

{ active: false, first: ' Jane', last: 'Smith ' }, // 9

{ active: true, first: 'Jesselin ', last: ' Alexandra ' }, // 17

]

// User :: { active: Bool, first: String, last: String }

// sumNameLength :: [User] -> Number

const sumNameLength = pipe(

filter(

propEq('active', true)

),

map(pipe(

pick(['first', 'last']),

map(

pipe(trim, length)

),

values,

sum,

)),

sum,

)

sumNameLength(users) // 36Now that we've filtered, we need to get the combined length of the "first" and "last" props for each user.

So what's this `pipe` all about?

Let's take this simpler example.

Sanitizing The Name

const sumNameLength = pipe(

filter(

propEq('active', true)

),

map(pipe(

pick(['first', 'last']),

map(

pipe(trim, length)

),

values,

sum,

)),

sum,

)This could look like this:

After selecting the props we care about, we need to find their true length.

const { ..., trim, length } from 'ramda'

const sumNameLength = pipe(

filter(

propEq('active', true)

),

map(pipe(

pick(['first', 'last']),

map(

(val) => {

const trimmed = trim(val)

const valLength = length(trimmed)

return valLength

}

),

values,

sum,

)),

sum,

)Sanitizing The Name

There's intermediate state that distracts from the aim.

map(

(val) => {

const trimmed = trim(val)

const valLength = length(trimmed)

return valLength

}

)map(

(val) => length(trim(val))

)map(

(val) => compose(length, trim)(val)

)map(

compose(length, trim)

)Better, but It's hard to see the data we're acting on.

We can compose these functions together!

And then it's easy to see that we can make this point-free.

FP Topics

1️⃣ Tools

- Higher Order Functions

- Currying

- Composition

2️⃣ Rules

- Purity

- Immutability

- No Side Effects

3️⃣ Concepts

- Declarative

- First Class Functions

- Point Free

// compose ::

// (Function, Function) ->

// Any a ->

// Any b

const compose = (f, g) => x => f(g(x))

const add1 = x => x + 1

const add2 = compose(add1, add1)

add2(2) // 4

add2(5) // 7

add2(10) // 12Functions built from functions.

Function composition is the process of combining two or more functions in order to produce a new function.

For example, the composition `f . g` (the dot means “composed with”) is equivalent to `f(g(x))` in JavaScript.

Composition

🎉 Full Breakdown 🎉

import { pipe, filter, map, pipe, pick, trim, length, values, sum } from 'ramda'

const users = [

{ active: true, first: 'Rob ', last: ' Hilgefort ' }, // 12

{ active: true, first: 'John ', last: ' Doe' }, // 7

{ active: false, first: ' Jane', last: 'Smith ' }, // 9

{ active: true, first: 'Jesselin ', last: ' Alexandra ' }, // 17

]

// User :: { active: Bool, first: String, last: String }

// sumNameLength :: [User] -> Number

const sumNameLength = pipe(

filter(propEq('active', true)), // [User]

map(pipe(

pick(['first', 'last']), // { first: String, last: String }

map(pipe(trim, length)), // { first: Number, last: Number }

values, // [Number]

sum, // Number

)), // [Number]

sum, // Number

)

sumNameLength(users) // 36

FP Rules

FP Topics

1️⃣ Tools

- Higher Order Functions

- Currying

- Composition

2️⃣ Rules

- Purity

- Immutability

- No Side Effects

3️⃣ Concepts

- Declarative

- First Class Functions

- Point Free

Purity

No outside scope.

Always returns a value.

// Impure

const maxNames = 5

const isValidNames = names => {

return names.length <= maxNames

}

isValidNames(names) // falseconst names = [

'Michael', 'Erin', 'Dylan',

'Wes', 'Bao', 'Taron',

]// Impure

let count

const getNamesCount = names => {

count = names.length

}

getNamesCount(names)

count // 6

// Pure

const isValidNames = names => {

const maxNames = 5

return names.length <= maxNames

}

isValidNames(names) // false// Pure

const getNamesCount = names => names.length

const count = getNamesCount(names)

count // 6Immutability ❌

Mutations can lead to inconsistent behavior and are hard to reason about.

Mutating shared state complicates debugging and reasoning about code.

// Given the following

const foo = { val: 2 }

const addOneObjVal = () => foo.val += 1

const doubleObjVal = () => foo.val *= 2

// Has a different effect on each call

addOneObjVal() // { val: 3 }

addOneObjVal() // { val: 4 }

addOneObjVal() // { val: 5 }

addOneObjVal() // { val: 6 }

// The order of execution changes

// the output of the function

addOneObjVal() // { val: 3 }

doubleObjVal() // { val: 6 }

// `foo` is reset to original

doubleObjVal() // { val: 4 }

addOneObjVal() // { val: 5 }

Immutability ✅

Objects can’t be modified after it’s created.

Immutability is a central concept of functional programming because without it, the data flow in your program is lossy. State history is abandoned, and strange bugs can creep into your software.

import { merge } from 'ramda'

// Given the following

const foo = { val: 2 }

const addOneObjVal =

x => merge(x, { val: x.val + 1})

const doubleObjVal =

x => merge(x, { val: x.val * 2})

addOneObjVal(foo) // { val: 3 }

addOneObjVal(foo) // { val: 3 }

addOneObjVal(foo) // { val: 3 }

doubleObjVal(foo) // { val: 4 }

doubleObjVal(foo) // { val: 4 }

doubleObjVal(addOneObjVal(foo))

// { val: 6 }

compose(doubleObjVal, addOneObjVal)(foo)

// { val: 6 }

Resources

This talk was heavily inspired by the following resources.

If you liked this talk and/or want to learn more, these are some of my favorite links to give out.