Outline: Episodes

-

Episode I

-

Recap: Pointers vs References

-

Passing by Value, Reference, and Pointers

-

Eigen's Passing by Value, Reference, and Pointers

-

-

Episode II

-

Function Inputs: Default arguments

-

Function Outputs: Output Parameters, Values, Tuples, or Structures

-

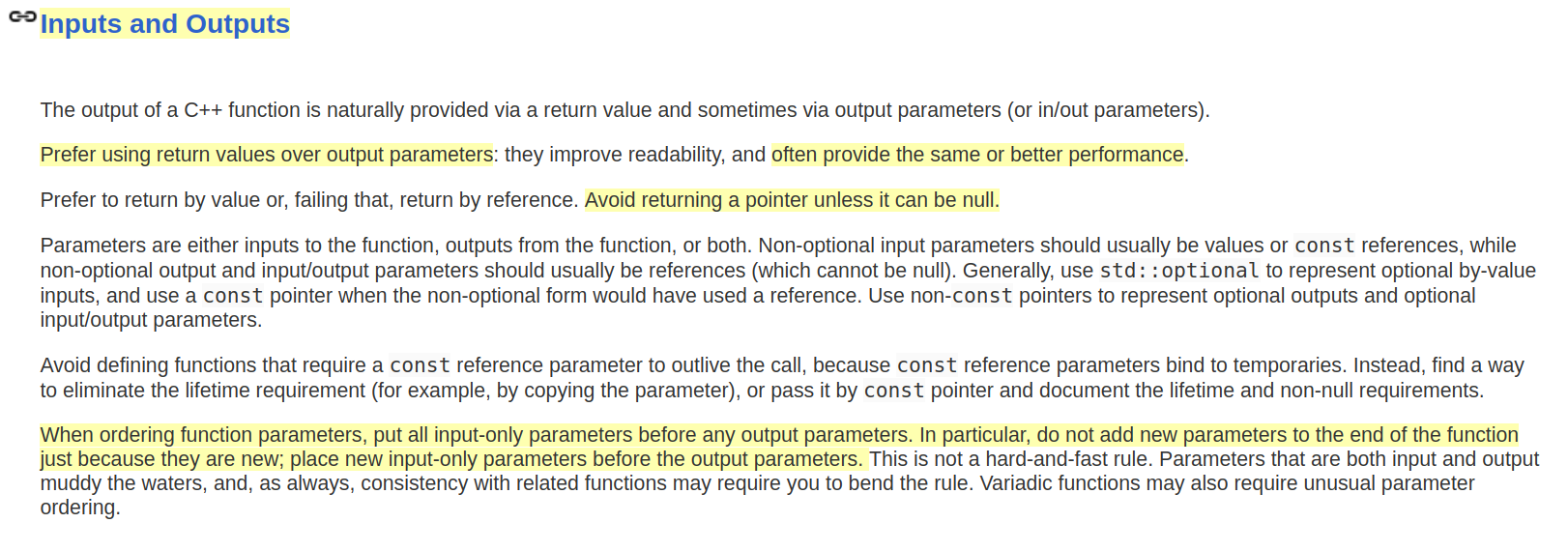

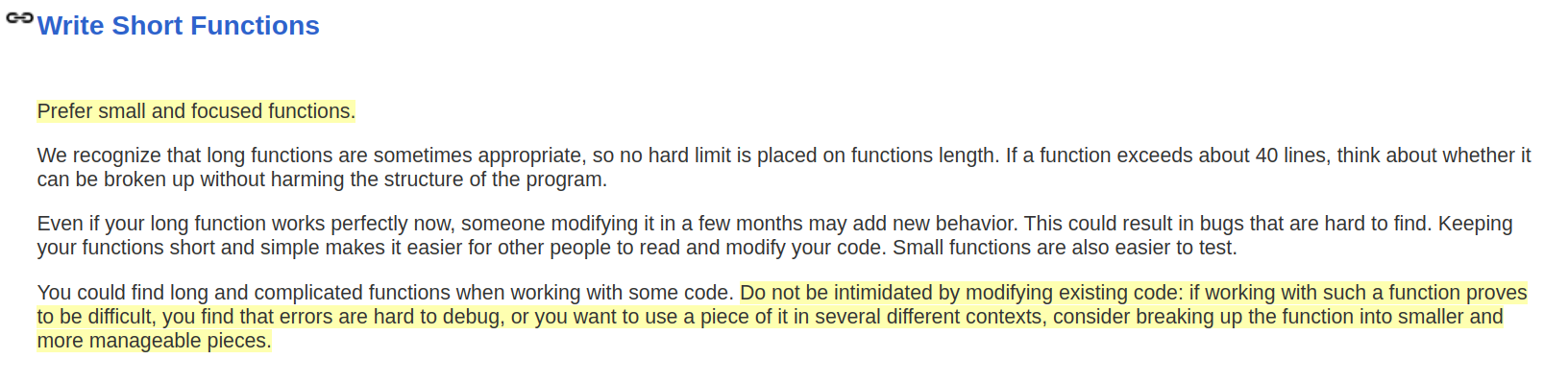

The Google C++ Guide on Functions

-

-

Episode III

-

Using Inline Functions

-

Writing the best getter function

-

Statements with Initializers in C++ 17

-

- Episode IV

- Templates

- Templates vs Auto

C++ Guide

(Episode I)

Shamel Fahmi

January, 2023

References and Pointers

-

Reference

-

It is an alias for a variable

-

It stores the value of the variable

-

The value is implicitly referenced.

-

-

Pointer

-

Is a variable that holds the memory address of another variable.

-

It stores the memory location of a variable; not the value.

-

You have to dereference the variable (*) to get its value.

-

// define a variable

int i = 3;

// Pointer

int * ptr = & i; // this is a pointer

// the * operator means that we are declaring a pointer.

// the & operator means that we want the address of the variable i

// Reference

int num1 = 20;

int &refNum1 = num1; // this is a reference

// Both num1 and refNum1 point to the same location.

// Changing num1 will change refNum1 (and vice versa).

std::cout << ptr << std::endl; // output: 0x7ffcc4fbe0c0

std::cout << *ptr << std::endl; // output: 3

std::cout << refNum1 << std::endl; // output: 20

std::cout << &refNum1 << std::endl; // output: 0x7ffcc4fbe0c4Passing by Value, Reference, or by Pointer

-

Passing by Value

-

Two copies of the variable are created with the same value.

-

The changes made to the variable inside the function are not reflected in the actual variable.

-

-

Passing by Reference

-

The memory location of the variable is passed in the function call.

-

The passed variable and the function's parameter are in the same location.

-

-

Passing by Pointer: Similar to passing by reference, but using pointers.

void exampleFunction1(int t){ t += 10; } // pass by value

void exampleFunction2(int &t){ t += 10; } // pass by reference

void exampleFunction3(int *t){ *t += 10; } // pass by pointer

int x = 0; exampleFunction1(x);

int y = 0; exampleFunction2(y);

int *z; *z = 0; exampleFunction3(z);

Passing by Value, Reference, or by Pointer

#include <iostream>

void exampleFunction1(int t){ t += 10; } // pass by value

void exampleFunction2(int &t){ t += 10; } // pass by reference

void exampleFunction3(int *t){ *t += 10; } // pass by pointer

int main()

{

int x = 0;

exampleFunction1(x);

int y = 0;

exampleFunction2(y);

int *z; *z = 0;

exampleFunction3(z);

std::cout << "x = " << x << std::endl;

std::cout << "y = " << y << std::endl;

std::cout << "z = " << *z << std::endl;

std::cout << "z = " << &z << std::endl;

std::cout << "z = " << z << std::endl;

return 0;

}

x = 0

y = 10

z = 10

z = 0x7ffd07309ed0

z = 0x7ffd07309fd0

Passing by Value, Reference, or by Pointer

-

Verdict: "Most objects use reference because it is quicker and does not have to deal with the additional features that the pointer gives. When you have to reassign a location, use a pointer. Otherwise, always prefer references!"

-

But, what if you do NOT want to change the value of the function's (input) parameter?

void Foo(const int & x){...}Passing Eigen objects by Value, Reference, or by Pointer

-

Passing objects by value is almost always a very bad idea in C++, as this means useless copies.

-

One should pass them by reference instead.

-

Passing fixed-size Eigen objects by value is not only inefficient but illegal or makes your program crash!

void my_function(Eigen::Vector2d v); // Do NOT do this.

void my_function(const Eigen::Vector2d& v); // Do this instead.

struct Foo { Eigen::Vector2d v; };

void my_function(Foo v); // Do NOT do this.

void my_function(const Foo& v); // Do this instead. Passing Eigen objects by Value, Reference, or by Pointer

/*!

* returns the position of a point with respect to the body, in body axes.

* The point in interest is defined by link_idx, and local_pos.

* @param local_pos : relative position in link frame, with respect to the link origin.

* @param link_idx : index of the link in which local_pos is defined.

* @return position of a point with respect to the body, in body axes

*/

template <typename T>

Vec3<T> FloatingBaseModel<T>::getPositionBody(const int link_idx,

const Vec3<T> & local_pos)

{

forwardKinematics();

Mat6<T> Xai = invertSXform(_Xa[link_idx]*invertSXform(_Xa[5])); // from link to torso

Vec3<T> link_pos_body = sXFormPoint(Xai, local_pos);

return link_pos_body;

}-

This is everywhere in the FloatingBaseModel. We are creating multiple copies of things that are not needed.

C++ Guide

(Episode II)

Shamel Fahmi

February, 2023

Default Arguments

-

Allows a function to be called without providing one or more trailing arguments. (like python)

#include <iostream>

int add(int x = 3, int y = 4){return x + y;}

int main()

{

std::cout << "output = " << add() << std::endl;

std::cout << "output = " << add(1) << std::endl;

std::cout << "output = " << add(1,2) << std::endl;

return 0;

}

// output = 7

// output = 5

// output = 3Default (Input) Arguments

enum printColors {black, red, green, blue, yellow, magenta, cyan, white};

template <typename T> void prettyPrint(T input, int color = printColors::black){

switch (color) {

case printColors::black:

std::cout << input << std::endl;

break;

case printColors::red:

std::cout << "\033[1;31m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

case printColors::green:

std::cout << "\033[1;32m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

case printColors::yellow:

std::cout << "\033[1;33m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

case printColors::blue:

std::cout << "\033[1;34m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

case printColors::magenta:

std::cout << "\033[1;35m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

case printColors::cyan:

std::cout << "\033[1;36m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

case printColors::white:

std::cout << "\033[1;37m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

}

}Function Outputs: Output Parameters

// Option 1: Output Parameters

#include <iostream>

void getQuotientRemainder(const int & dividend, const int & divisor, int & quotient, int & remainder){

quotient = dividend / divisor;

remainder = dividend % divisor;

}

int main() {

int a_quotient, a_remainder;

getQuotientRemainder(5, 2, a_quotient, a_remainder);

std::cout << "Option 1: Quotient " << a_quotient << " Remainder " << a_remainder << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Function Outputs: Output Values

// Option 2: Output Values

#include <iostream>

int getQuotient(const int & dividend, const int & divisor){return dividend / divisor;}

int getRemainder(const int & dividend, const int & divisor){return dividend % divisor;

int main() {

int another_quotient = getQuotient(5, 2);

int another_remainder = getRemainder(5, 2);

std::cout << "Option 2: Quotient " << another_quotient << " Remainder " << another_remainder << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Function Outputs: Output Structures

// Option 3: Output Object/Structure

#include <iostream>

struct myQuotientRemainderStruct {

int quotient;

int remainder;

};

myQuotientRemainderStruct getQuotientRemainder(const int & dividend, const int & divisor){

myQuotientRemainderStruct a_quotient_remainder_struct;

a_quotient_remainder_struct.quotient = dividend / divisor;

a_quotient_remainder_struct.remainder = dividend % divisor;

return a_quotient_remainder_struct;

}

int main() {

myQuotientRemainderStruct a_quotient_remainder_struct = getQuotientRemainder(5, 2);

std::cout << "Option 3: Quotient " << a_quotient_remainder_struct.quotient;

std::cout << " Remainder " << a_quotient_remainder_struct.remainder << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Function Outputs: Output Tuples

// Option 4: Tuples

#include <iostream>

#include<tuple> // for tuple

std::tuple<int, int> getQuotientRemainderUsingTuple(const int & dividend, const int & divisor){

int quotient = dividend / divisor;

int remainder = dividend % divisor;

return std::make_tuple(quotient, remainder);

}

int main() {

int tuple_quotient, tuple_remainder;

std::tie(tuple_quotient, tuple_remainder) = getQuotientRemainderUsingTuple(5, 2);

std::cout << "Option 2: Quotient " << tuple_quotient << " Remainder " << tuple_remainder << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Function Outputs: Full Code

// Online C++ compiler to run C++ program online

#include <iostream>

#include<tuple> // for tuple

// Option 1: Output Parameters

void getQuotientRemainder(const int & dividend, const int & divisor, int & quotient, int & remainder){

quotient = dividend / divisor;

remainder = dividend % divisor;

}

// Option 2: Output Values

int getQuotient(const int & dividend, const int & divisor){return dividend / divisor;}

int getRemainder(const int & dividend, const int & divisor){return dividend % divisor;}

// Option 3: Output Object/Structure

struct myQuotientRemainderStruct {

int quotient;

int remainder;

};

myQuotientRemainderStruct getQuotientRemainder(const int & dividend, const int & divisor){

myQuotientRemainderStruct a_quotient_remainder_struct;

a_quotient_remainder_struct.quotient = dividend / divisor;

a_quotient_remainder_struct.remainder = dividend % divisor;

return a_quotient_remainder_struct;

}

// Option 4: Tuples

std::tuple<int, int> getQuotientRemainderUsingTuple(const int & dividend, const int & divisor){

int quotient = dividend / divisor;

int remainder = dividend % divisor;

return std::make_tuple(quotient, remainder);

}

int main() {

// Write C++ code here

std::cout << "Hello world!" << std::endl;

// Option 1

int a_quotient, a_remainder;

getQuotientRemainder(5, 2, a_quotient, a_remainder);

std::cout << "Option 1: Quotient " << a_quotient << " Remainder " << a_remainder << std::endl;

// Option 2

int another_quotient = getQuotient(5, 2);

int another_remainder = getRemainder(5, 2);

std::cout << "Option 2: Quotient " << another_quotient << " Remainder " << another_remainder << std::endl;

// Option 3

myQuotientRemainderStruct a_quotient_remainder_struct = getQuotientRemainder(5, 2);

std::cout << "Option 3: Quotient " << a_quotient_remainder_struct.quotient << " Remainder " << a_quotient_remainder_struct.remainder << std::endl;

// Option 4

int tuple_quotient, tuple_remainder;

std::tie(tuple_quotient, tuple_remainder) = getQuotientRemainderUsingTuple(5, 2);

std::cout << "Option 2: Quotient " << tuple_quotient << " Remainder " << tuple_remainder << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Using Function Outputs in Robot Software

-

Let's take the WBC as an example. We want to run the WBC and get the result from the QP.

-

The result from the QP can vary (torques, body and joint accelerations, GRFs, etc.).

-

Output Parameters: You still are not sure what are the inputs and what are the outputs.

-

Output Values: In this case, you will need to write multiple getters.

-

Output Struct: Probably the best thing to do.

_dwbc_runner->run(_dwbc_data, *this->_data, torques, accelerations);_dwbc_runner->run(_dwbc_data, *this->_data);

torques = _dwbc_runner->getTorqueOutput();

accelerations = _dwbc_runner->getAccelerationOutput();Using Function Outputs in Robot Software

-

Output Struct: Probably the best thing to do.

// in dWBC_runner.hpp

template<typename T> struct dWBC_result

{

DVec<T> tau_ff; // joint feedforward torque

DVec<T> q_des; // joint position setpoint

DVec<T> qd_des; // joint velocity setpoint

DVec<T> qdd_des; // joint accelerations, from the QP

int QP_flag; // 0 if QP is feasible, otherwise QP_swift exit code (infeasible)

};

// In Humanoid_State_Balance.cpp

dWBC_result<T> dwbc_res = _dwbc_runner->run(_dwbc_data, *this->_data);Google C++ Guide

Google C++ Guide

C++ Guide

(Episode III)

Shamel Fahmi

February, 2023

Outline

-

Inline Functions

-

Writing the best getter function

-

Statements with Initializers in C++ 17

Inline Functions in Robot Software

// In Humanoid_State_Balance.h

// Behavior to be carried out when exiting a state

virtual inline void onExit(){ return; }Infline functions

-

What happens when you call a function? Function call overhead vs execution overhead.

-

C++ provides inline functions to reduce the function call overhead.

-

Inline function is a function that is expanded in line when it is called.

-

When called, the code of inline functions gets inserted or substituted at the point of the function call.

-

This substitution is performed by the compiler at compile time.

virtual inline void onExit(){ return; }Writing the Best Getter Function

inline <type> & getVariable() const { return this->variable; }- The constant operator denies permission to change the value of a variable or a function.

void setIntVariable(const int & x) {this->variable = x}- We know how write a "good" setter function.

- What about a getter function?

inline const <type> & getVariable() const { return this->variable; }Writing the Best Getter Function

int get_data() {

++x;

return x;

}int get_data() const {

++x;

int y = x;

y++;

return x;

}C++17: If Statements with Initializers

if (init; cond) { /* ... */ }- C++17 allows if and switch statements to include an initializer.

-

This syntax lets you keep the scope of variables as tight as possible.

- When to use it?

- When you need a new variable for use within the if statement that is not needed outside of it.

- Since the variable’s scope is now small, its name can be shorter, too.

C++17: If Statements with Initializers

#include <iostream>

int main() {

// Example 1

int x = 1;

if (x == 1) { x++; }

std::cout << x << std::endl;

// Example 2

{

int z = 1;

if (z == 1) { z++; }

}

std::cout << z << std::endl; // <-- compilation error, z is out of scope

// Example 3

if (int y = 1; y == 1) { y++; }

std::cout << y << std::endl; // <-- compilation error, z is out of scope

return 0;

}C++ Guide

(Episode IV)

Shamel Fahmi

February, 2023

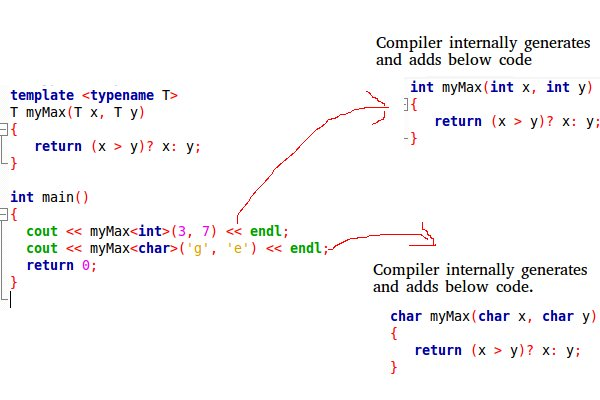

Templates

-

Pass data type as a parameter so that we don’t need to write the same code for different data types.

void lazyPrint(const <type> & input){ std::cout << input << std::endl; }

void lazyPrint(const double & input){ std::cout << input << std::endl; }

void lazyPrint(const int & input){ std::cout << input << std::endl; }

void lazyPrint(const Eigen::VectorXd & input){ std::cout << input << std::endl; }Templates

-

Templates are expanded at compiler time.

-

Examples of function templates are sort(), max(), min(), printArray().

Templates

-

Class Templates are possible when a class defines something that is independent of the data type.

-

Can be useful for classes like LinkedList, BinaryTree, Stack, Queue, Array, etc.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

template <typename T> class Array {

private:

T* ptr;

int size;

public:

Array(T arr[], int s);

void print();

};

template <typename T> Array<T>::Array(T arr[], int s)

{

ptr = new T[s];

size = s;

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++)

ptr[i] = arr[i];

}

template <typename T> void Array<T>::print()

{

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++)

cout << " " << *(ptr + i);

cout << endl;

}

int main()

{

int arr[5] = { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 };

Array<int> a(arr, 5);

a.print();

return 0;

}Templates

-

Can there be more than one argument to templates?

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

template <class T, class U> class A {

T x;

U y;

public:

A() { cout << "Constructor Called" << endl; }

};

int main()

{

A<char, char> a;

A<int, double> b;

return 0;

}Templates

-

Can we specify a default value for template arguments?

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

template <class T, class U = char> class A {

public:

T x;

U y;

A() { cout << "Constructor Called" << endl; }

};

int main()

{

A<char> a; // This will call A<char, char>

return 0;

}Using Templates vs. Auto: Robot-Software Example

enum colors {red, green, blue, white};

template <typename T> void prettyPrint(T input, int color = colors::white){

switch (color) {

case printColors::red:

std::cout << "\033[1;31m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

case printColors::green:

std::cout << "\033[1;32m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

case printColors::blue:

std::cout << "\033[1;34m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

case printColors::white:

std::cout << "\033[1;37m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

}

}enum colors {red, green, blue, white};

void prettyPrint(auto input, int color = colors::white){

switch (color) {

case printColors::red:

std::cout << "\033[1;31m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

case printColors::green:

std::cout << "\033[1;32m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

case printColors::blue:

std::cout << "\033[1;34m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

case printColors::white:

std::cout << "\033[1;37m" << input <<"\033[0m\n";

break;

}

}Templates: Pros and Cons

Pros

-

Use templates in situations that result in duplication of the same code for multiple types.

-

Because their parameters are known at compile time, template classes are more typesafe, and could be preferred over run-time resolved code structures (eg. auto).

Cons

- Some compilers exhibited poor support for templates. So, it could decrease code portability.

- Since the compiler generates additional code for each template type, templates can lead to code bloat, resulting in larger executables.

- Can lead to longer build times.

- It can be difficult to debug code that is developed using templates. Since the compiler replaces the templates, it becomes difficult for the debugger to locate the code at runtime.

To ADD:

- Eigen (5)

- Github (3)

- Explicit (0)

- Exceptions (3)

- Classes - Structs

- Smart and Shared ptrs

- Bash

- L-values and R-values

- Rule of 3-warning

- Docker