Hear Us Out! Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and Their Music

Lesson Hub 7:

Mobilizing Asian America

What led to the rise of the Asian American movement?

How did taiko drumming come to be associated with the Asian American movement?

How can the Arts contribute to social justice movements?

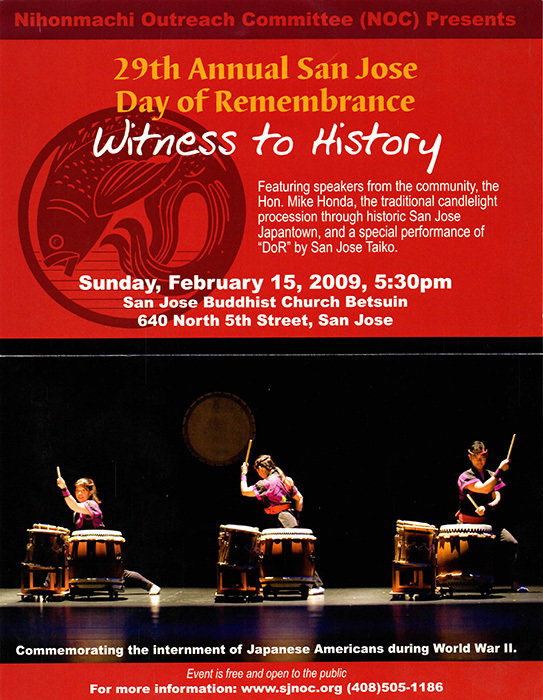

San Jose Taiko, by Bob Hsiang. Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

Lesson Hub 7: Mobilizing Asian America

CREATIVE CONNECTIONS

30+ MIN

30+ MIN

15+ MIN

HISTORY & CULTURE

MUSIC LISTENING

"#Solidarity." Millions March in New York City, December 13, 2014, by Marcela McGreal. CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

Legacy of the Asian American Movement

Path 1

30+ minutes

International Hotel, 848 Kearny Street in San Francisco August, 1977, photo by Nancy Wong. CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

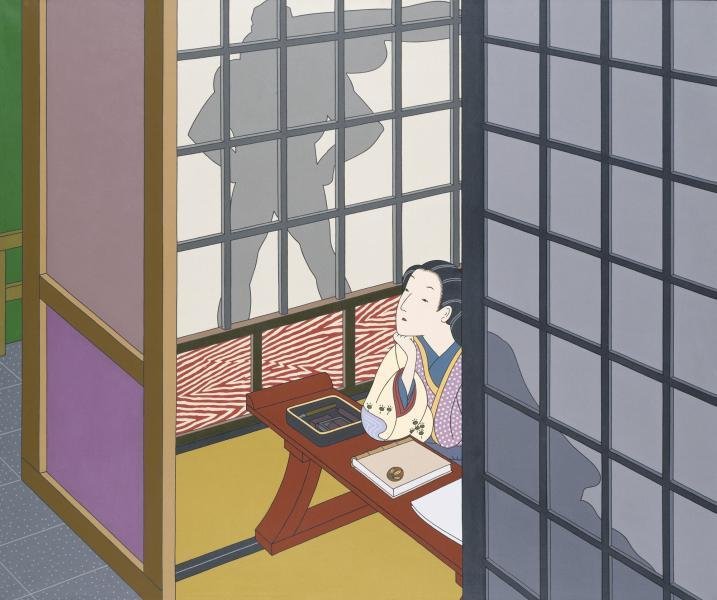

Opening Listening Activity: "Yellow Pearl"

In this song, the musicians sing about how the "yellow peril" will become the "yellow pearl."

Listen to the opening song from the 1973 Paredon album, A Grain of Sand, while following along with the lyrics.

What is "yellow peril"?

How do the lyrics express Asian American pride?

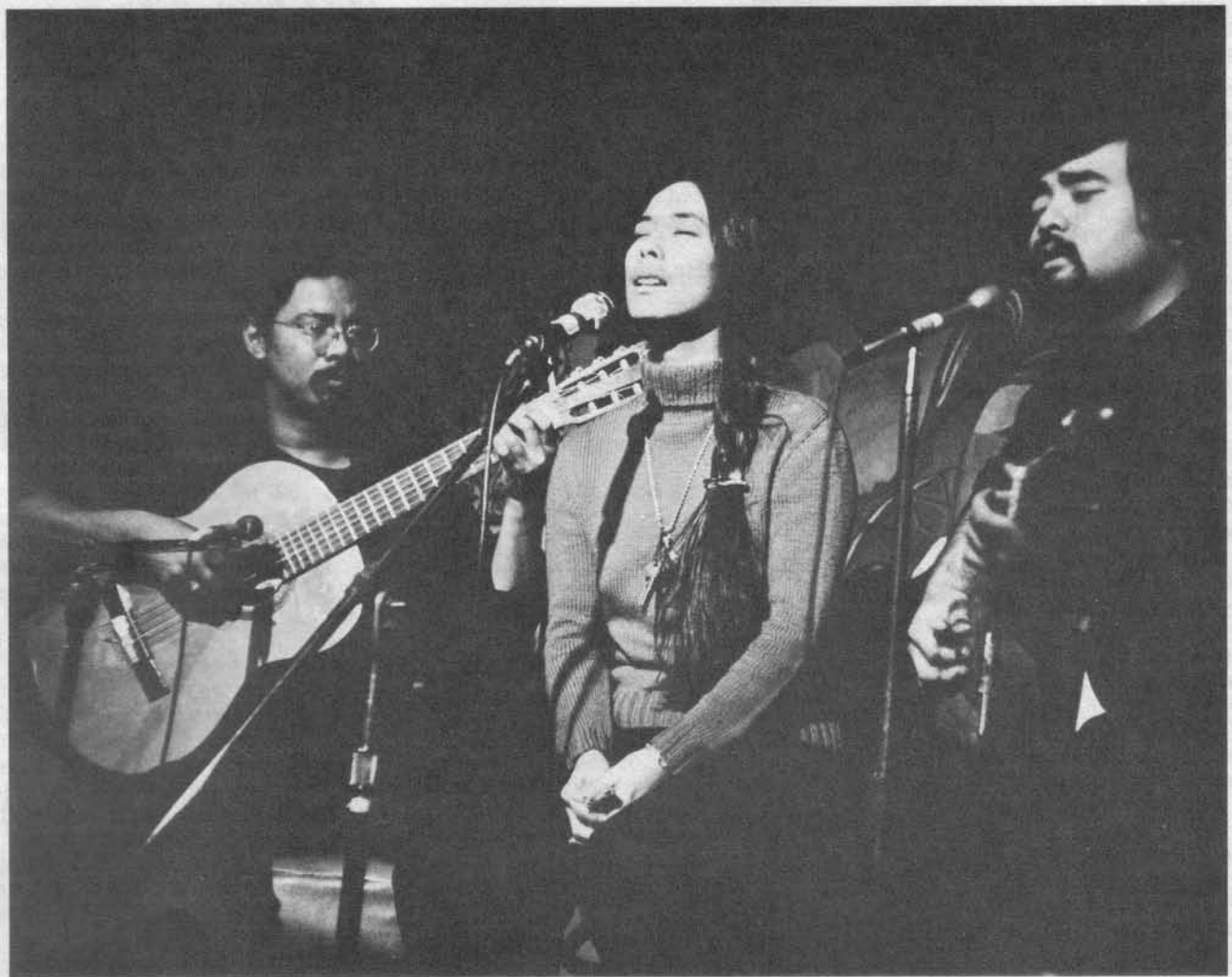

Charlie Chin, Nobuko Miyamoto, and Chris Iijima, unknown photographer. Paredon Records.

Asian American Activism and Cross-Racial Coalitions

Because of the long history of violence and legal discrimination against Asian Americans, there is also a long history of political and labor activism in Asian American communities.

About the video: Agustin Lira created music for the Chicano movement and the United Farm Workers. In this interview excerpt, he discusses cross-racial coalitions, specifically - the key role that Filipino farm workers played during the joint Filipino-Chicano Delano Grape Strike from 1965 to 1970.

Much Asian American activism across the political spectrum relies on cross-racial coalitions.

Jason Ma wrote a musical entitled "Gold Mountain" that is inspired by this strike. Here's a preview of a production of this musical on KSL TV in Utah in November 2021.

The workers demanded ten-hour workdays and wages equivalent to those of white workers.

In 1867, Chinese railroad workers went on strike after a tunnel explosion killed six (five of whom were Chinese).

However, the strike showed railroad tycoons that they could not take Chinese workers for granted.

The owner of the railroad ended the strike after eight days by cutting off all provisions to Chinese workers.

Early Examples of Asian American Activism

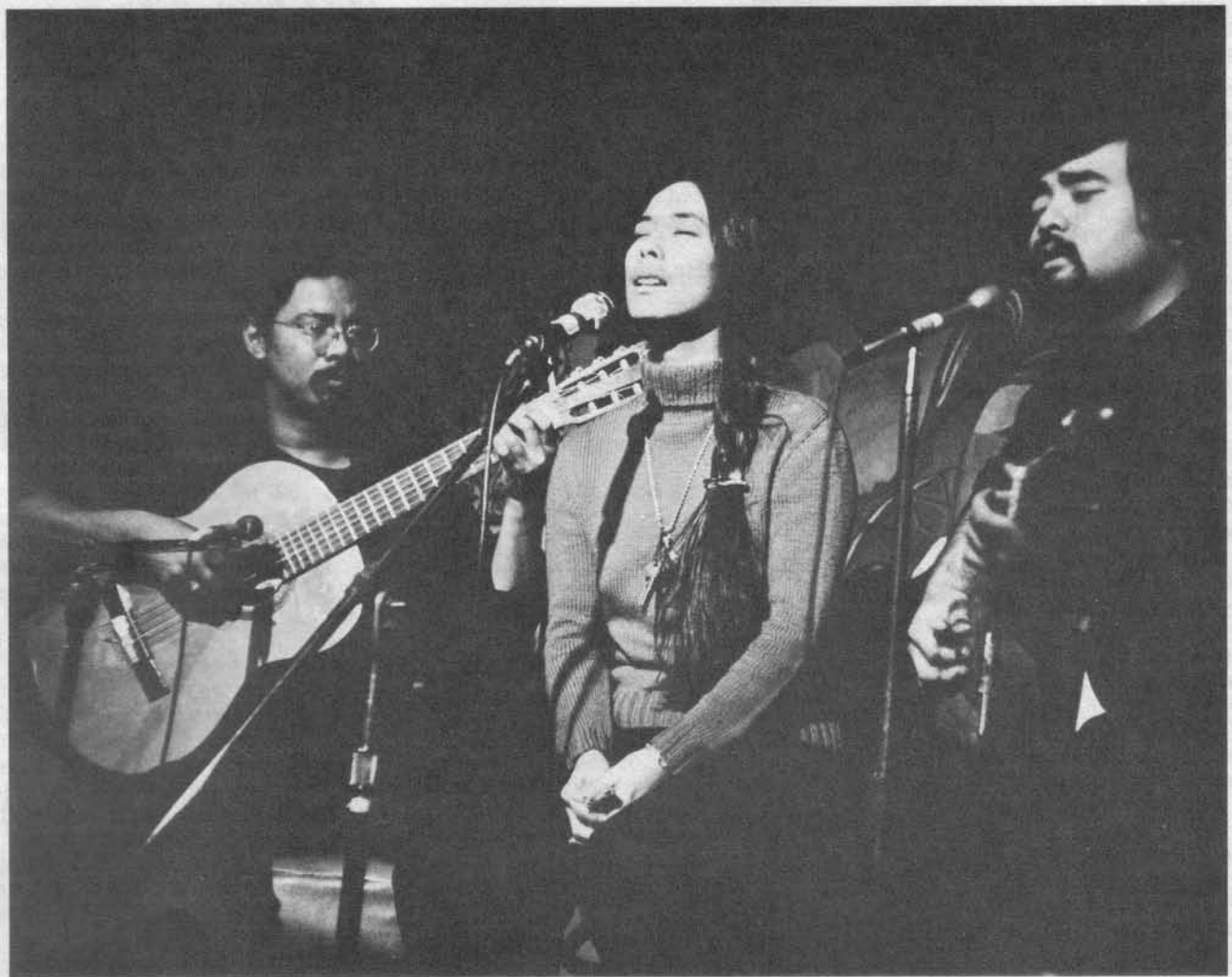

Silent Protests: Angel Island Poems

There, many Chinese and some other arrivals carved poems onto the walls of the barracks protesting their extended detentions and often deportations.

Poem Carved on the Walls of a Lavatory at the Angel Island Immigration Station, author unknown. Photo by Ying Diao. Smithsonian Magazine.

Under some circumstances, the protests of Asian Americans could not be public.

Angel Island, located near San Francisco, was the main immigration station charged with enforcing racist Asian exclusion laws in the early 1900s.

Setting Angel Island Poems to Music

The carved poems on Angel Island have inspired many musicians. In the late 1990s, Jon Jang wrote Island: Immigrant Suite #1 and #2. The first suite is for an ensemble of Chinese and Western instruments that performs in a style inspired by free jazz. This excerpt contains the fourth movement.

Jang's grandparents were detained and interrogated on Angel Island.

Protesting through Lawsuits

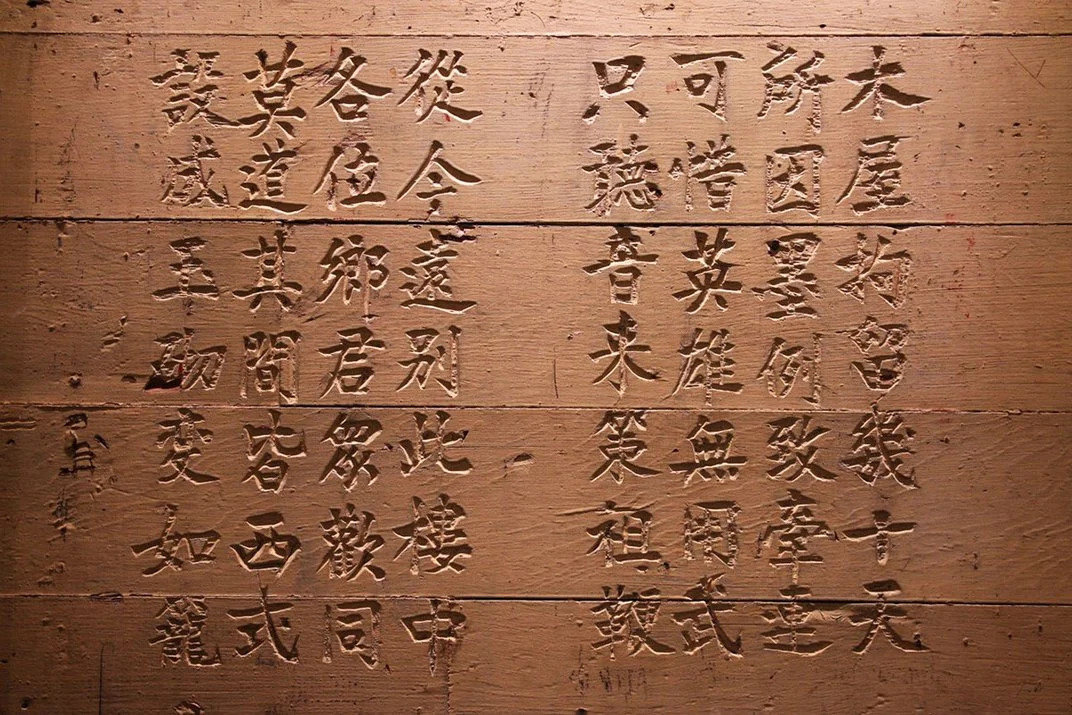

Bhagat Singh Thind in U.S. Army Uniform, unknown photographer. South Asian American Digital Archive.

Asian Americans also used courts to fight for rights.

Some challenges were successful, but others were not.

These cases demonstrate the limits of assimilation in the U.S.

In the 1920s, several Asian Americans unsuccessfully tried to fight for citizenship (Ozawa v. U.S.; Thind v. U.S.) and the right to attend white schools in the South (Lum v. Rice) by claiming Whiteness.

Korematsu v. U.S.

In a 6-3 decision, the Court ruled against Korematsu, arguing that the government can take individuals' or groups' civil rights in situations of "military necessity."

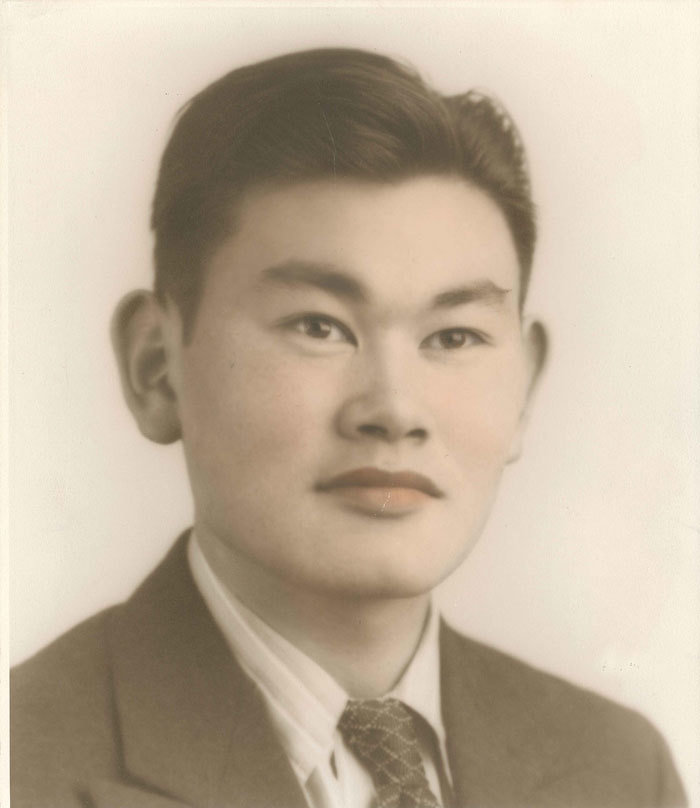

Fred Korematsu in the 1940s, unknown photographer. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0, via Densho Encyclopedia.

When FDR issued Executive Order 9066 incarcerating Japanese Americans on the west coast, a man by the name of Fred Korematsu decided to remain at his residence in San Leandro, CA. He was arrested and convicted.

Ultimately, this case went all the way to the Supreme Court, where he and his lawyers argued that E.O. 9066 was unconstitutional.

The Legacy of Korematsu

Although Korematsu's conviction was voided in 1983, the Supreme Court's decision that "military necessity" can lead to the curtailing of civil rights remained.

However, did the Court actually create a new precedent that resembles Korematsu in many ways?

Fred Korematsu in 2009, uploaded by Timothyjosephwood. Courtesy of the family of Fred T. Korematsu. CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In Trump v. Hawaii (2018), the court disagreed about the meaning of Korematsu, but both sides repudiated it. In her dissent, Justice Sotomayor wrote, "This formal repudiation of a shameful precedent is laudable and long overdue.”

Involvement in Homeland Politics

Examples include:

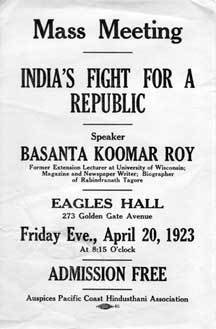

- The Ghadar Party, founded by members of the South Asian diaspora who want to overthrow British colonialism.

- Chinese Americans fundraising for the 1911 Revolution in China and for war efforts in the 1930s.

Poster for an Indian Independence Meeting in San Francisco in 1923. University of California Berkley Libraries.

In the early 20th century, many Asian Americans were also involved in the politics of their homeland.

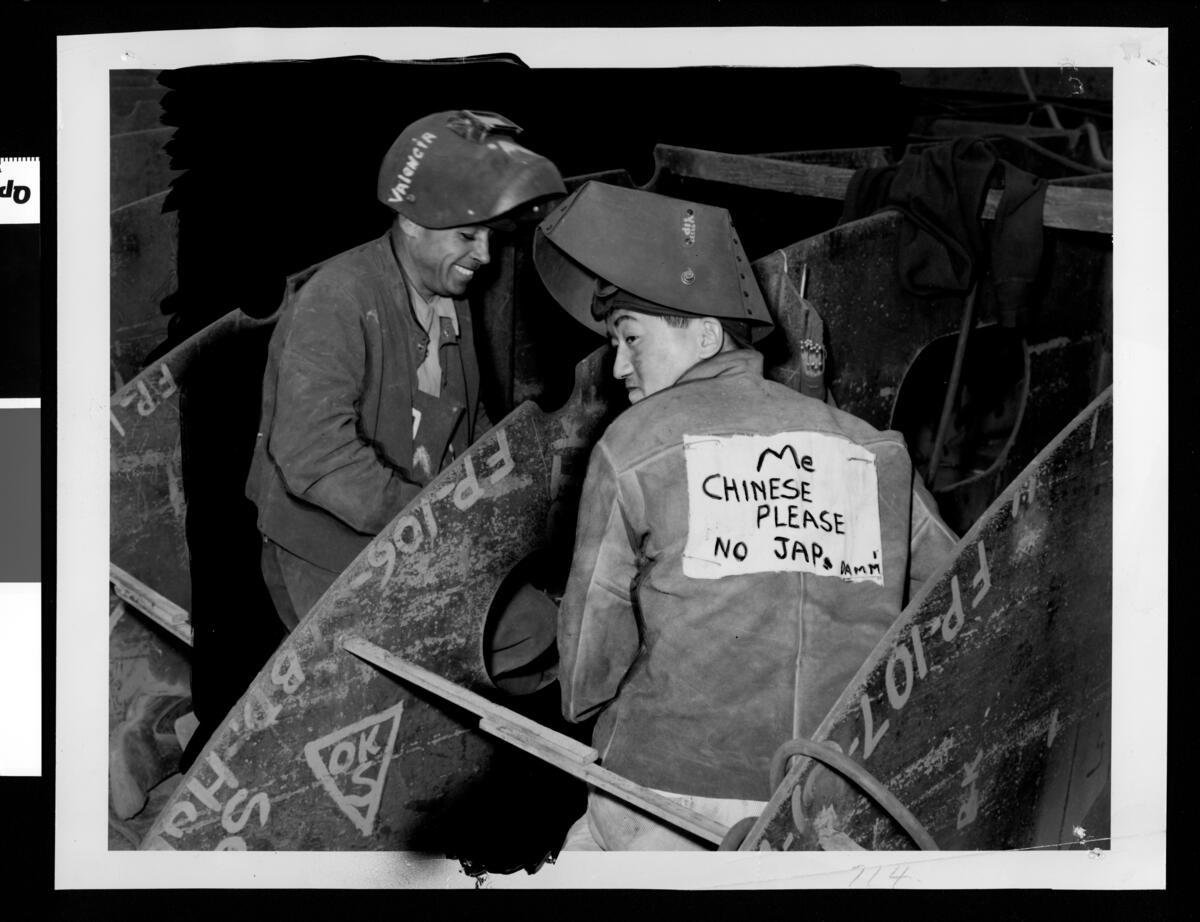

From Ethnicities to Race, Before the 1960s

- Different Asian ethnicities often lived very different lives; and

- Homeland politics often made coalitions between different ethnicities difficult.

"Me Chinese Please," unknown photographer. University of Southern California Libraries.

Before the mid-1960s, Asian Americans did not think of themselves as a single racial group. Two key reasons are:

From Ethnicities to Race, During and After the 1960s

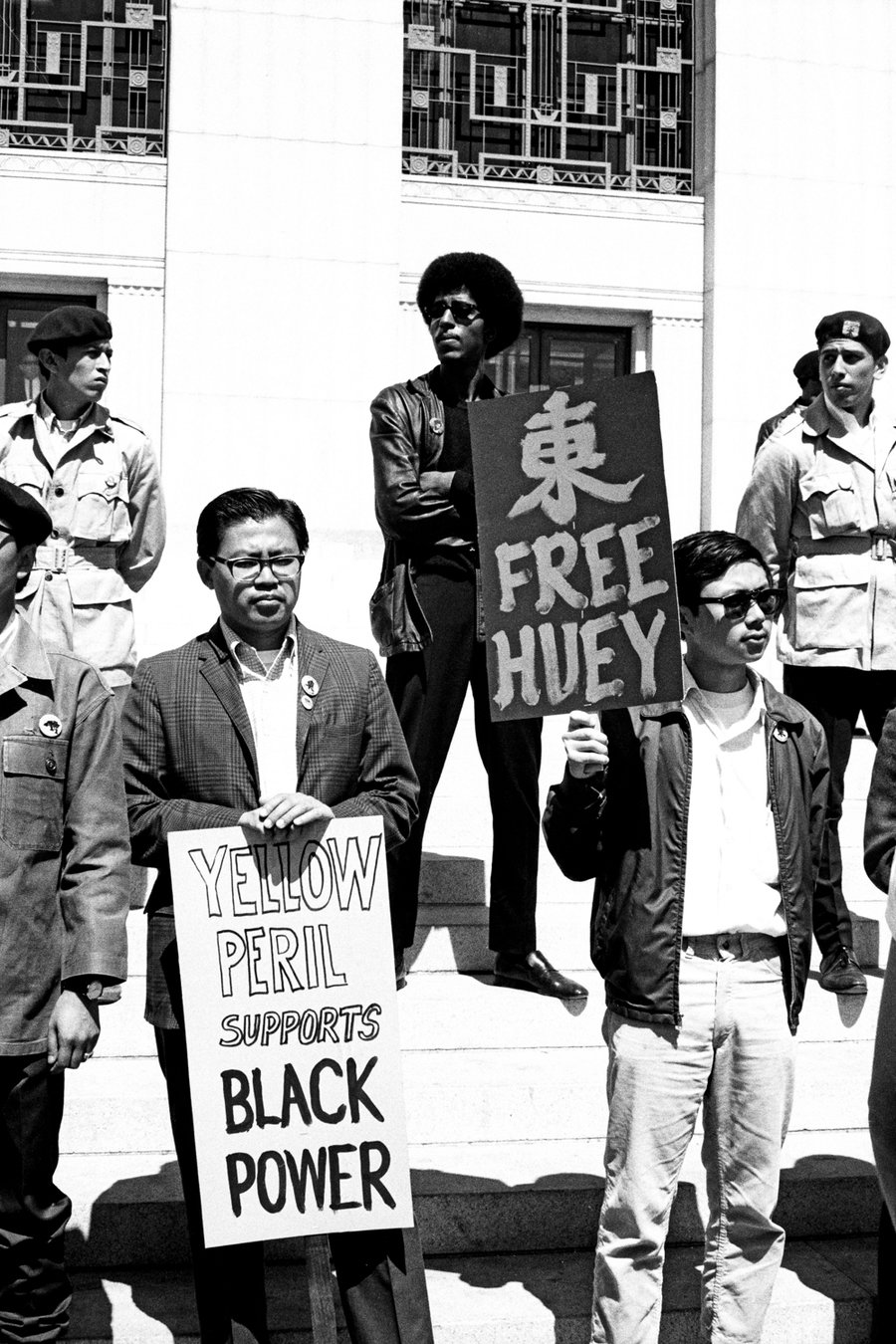

In the 1960s, more radical Asian American activists participated in the Civil Rights and Anti-war movements, and started to see the political potential of large coalitions.

In this short video clip, Shui Mak Ka, a lead organizer of the 1982 Garment Workers' Strike in New York City, discusses her approach to giving a big speech in a union rally.

Cross-Racial Coalitions: Black Power and the Asian American Movement

The pioneers of the Asian American movement in the late 1960s were heavily influenced by the Black Power movement, which holds political stances that emphasize:

- Racial pride

- Self-determination, particularly community control over institutions (education/police)

- Fair housing and employment

Asian American Demonstrators Rally for Black Panther Party Co-Founder Huey P. Newton's Release from Prison in 1969, by Roz Payne. Roz Payne Sixties Archive, University of Nebraska Lincoln.

Three Early Organizations

Anti-War Rally in San Francisco, 1969, by Ray Okamura. Originally published in Gidra, via Densho Encyclopedia.

-

Asian American Political Alliance (San Francisco and Berkeley, 1968-69): Helped lead student strikes (see next slide).

- The Red Guard Party (San Francisco, 1969-73): Directly modeled on the Black Panther party. They focused their efforts on SF Chinatown.

- Asian Americans for Action (NYC, 1969-80): Dedicated to opposing the Vietnam War and nurturing grassroots Asian American solidarity.

Campus Strikes

The biggest success of the early Asian American movement came about through the student strikes at San Francisco State College (1968-69) and UC Berkeley (1969). Asian American activist students joined other students of color as members of the Third World Liberation Front to demand:

- Changing how the university produces and disseminates knowledge about BIPoCs

- Giving BIPoCs greater access to admission and financial aid

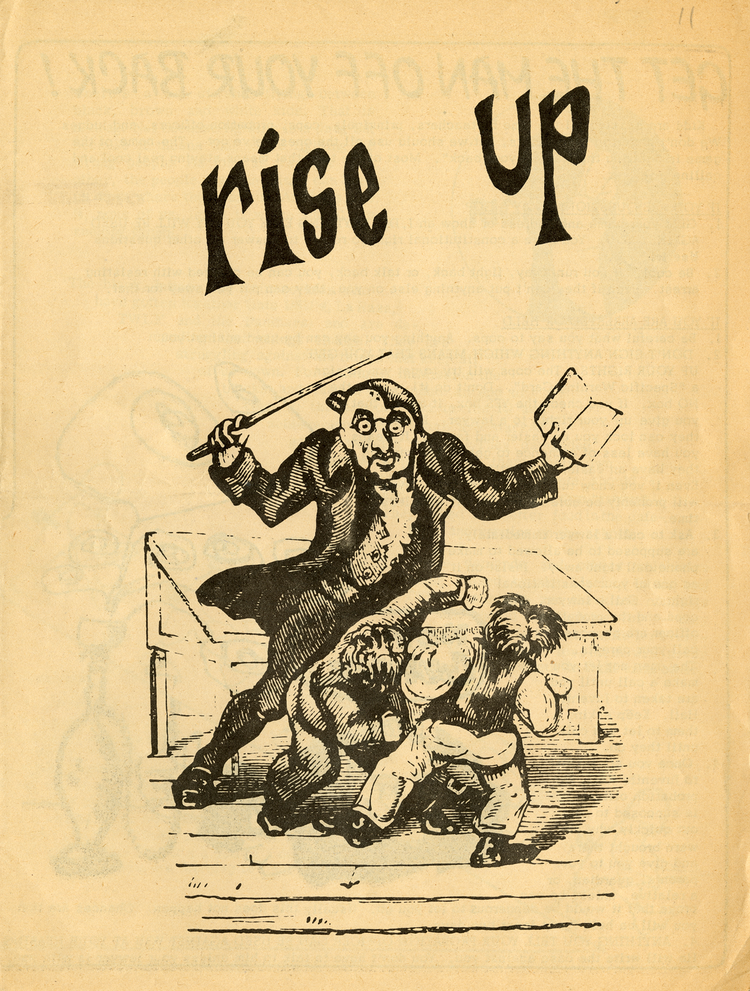

Rise Up, unknown artist. San Francisco State University.

The Birth of Ethnic Studies

The five-month strike at SF State and the three-month strike at Berkeley ended when both universities agreed to create ethnic studies departments.

The flourishing of these programs at hundreds of universities today demonstrates the far-reaching influences of these strikes.

College of Ethnic Studies Logo, unknown artist. San Francisco State University.

Helping Communities throughout the 1970s

The efforts of the Asian American Movement were most visible in large Asian enclaves. In San Francisco, Los Angeles, Honolulu, Seattle, New York, Philadelphia and several other cities, activists in the Asian American Movement in the 1970s worked to:

- Preserve and sustain traditional Asian neighborhoods

- Fight for affordable housing

- Provide social services

- Organize labor and fight discriminatory employment practices

Preserving Neighborhoods

Activists fought against redevelopment in many Asian enclaves, including Seattle's International District, Los Angeles' Little Tokyo, and Philadelphia's Chinatown.

In the late 1960s, Philadelphia unveiled plans to build a highway that cut across Chinatown. Chinatown residents rose up, and reached a compromise: a sunken expressway that allowed for pedestrians and local car traffic at street level.

Top: Help Save Chinatown!. unknow artist. Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Bottom: Vehicles Move Along The Vine Street Expressway, by Donald D. Groff. Via The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.

Fighting for Affordable Housing

In numerous cities, Asian American movement activists fought for affordable housing. Many were particularly concerned about housing for elderly members of their community.

The most famous of these battles took place at the International Hotel in San Francisco, where many older Filipino Americans lived. Although ultimately unsuccessful, activists managed to delay the eviction of the tenants by almost a decade.

Protesters Lock Arms to Prevent the Eviction of the International Hotel Tenants, 1977, by Nancy Wong. CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Providing Social Services

Asian American activists focused much of their energy on social services, a direct influence from the work of the Black Panthers. These social services included:

- Providing meals

- Repairing and renovating affordable housing in poor condition

- Starting free health clinics

- Offering legal services

The Story of The 1971 Chinatown Health Fair. Uploaded by the National Museum of American History.

Fighting for Workers' Rights

The Asian American movement also involved labor organizing in the fight against discriminatory hiring practices.

A particularly important event was the Jung Sai Strike of 1974-75 by 135 mostly middle-aged Chinese American women who wanted to unionize. They had worked for low wages in poor conditions and were regularly facing harassment and intimidation.

Jung Sai Garment Workers Picketing in San Francisco, 1974, by Cathy Cade. Via Found SF: The San Francisco Digital History Archive.

Jung Sai Strikers

Striking Jung Sai garment workers often faced arrest, police harassment, and unsympathetic judges. A truck driver who worked for the factory owner even ran over several workers.

Ultimately, the workers prevailed. The court ruled that the factory had to hire back all workers employed at the start of the strike, give them back pay, and negotiate with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union.

135 Strikers From The Chinatown Jung Sai Garment Factory Rallied at Portsmouth Square in 1974, unknown photographer. Via Found SF..

Time for Reflection

- Who is providing necessary social services?

- Who should be providing these social services?

- Are these social services accessible?

-

Is your community threatened in some way?

- If so, who is fighting to preserve and sustain the community?

As you have learned, activists from the Asian American movement worked to help their communities get services and fight for survival.

In your own community (ethnic, racial, geographic, or professional) ...

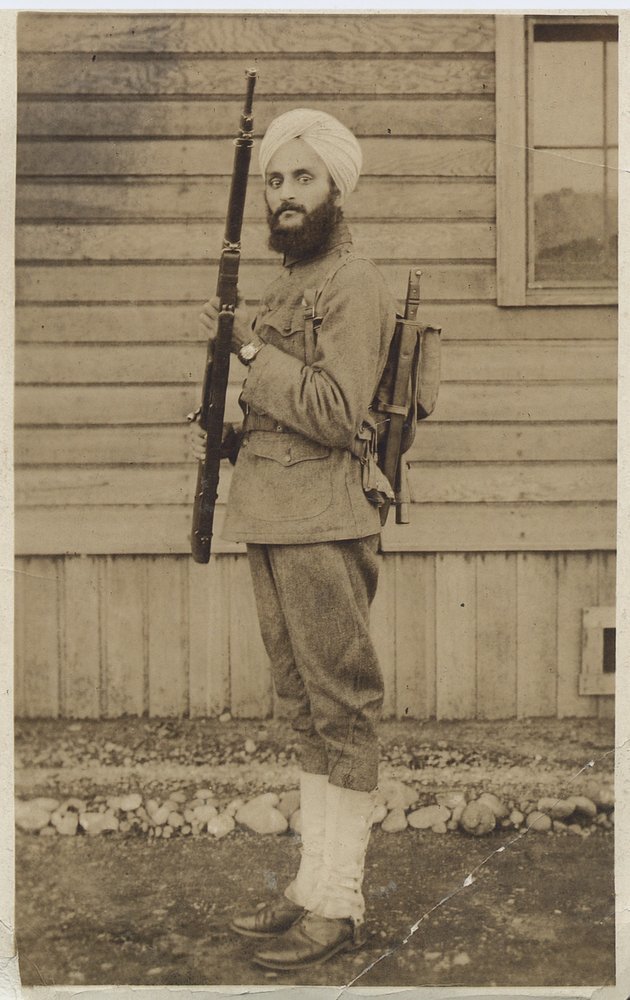

Asian American Consciousness

Perhaps the most long-lasting aspect of the Asian American movement's work is the development of an Asian American identity that is defined primarily by community members.

Artists--including many who participated in organizations you can research in Path 3--were instrumental in developing this new racial identity.

Developing an Asian American Identity

Developing an Asian American identity means:

- Recognizing that your community has stories that are worth telling.

- Recognizing that your community's experiences are different from those of non-Asian American communities.

- Recognizing commonalities between the diverse experiences of your community, particularly similar forms of exclusion and similar strategies for resistance and healing.

- Recognizing the limits of assimilation.

Music of the Asian American Movement

The most famous example of this is the trio of Chris Iijima, Nobuko Miyamoto and Charlie Chin, who sang the song you listened to at the beginning of this Path, "Yellow Pearl."

Many were influenced by the folk music revival of the 1960s.

Musicians involved in the Asian American movement, who helped develop and sustain this Asian American identity, created music in a wide variety of genres.

Asian American Music and the Folk Revival

Another group that performed folk music during the time of the Asian American movement was the San Jose-based Yokohoma, California.

"Tanforan (Is Anybody There?)" is the opening track on Yokohoma, California's eponymous album (1977).

The band's song, "Tanforan (Is Anybody There?)," memorialized Tanforan, an assembly center south of San Francisco where Japanese Americans gathered before they departed for incarceration camps in 1942.

What is the story behind these lyrics?

Asian Sounds in Asian American Music

Unlike the folk-influenced artists, some musicians involved in the Asian American movement wanted to center Asian instruments in their music making.

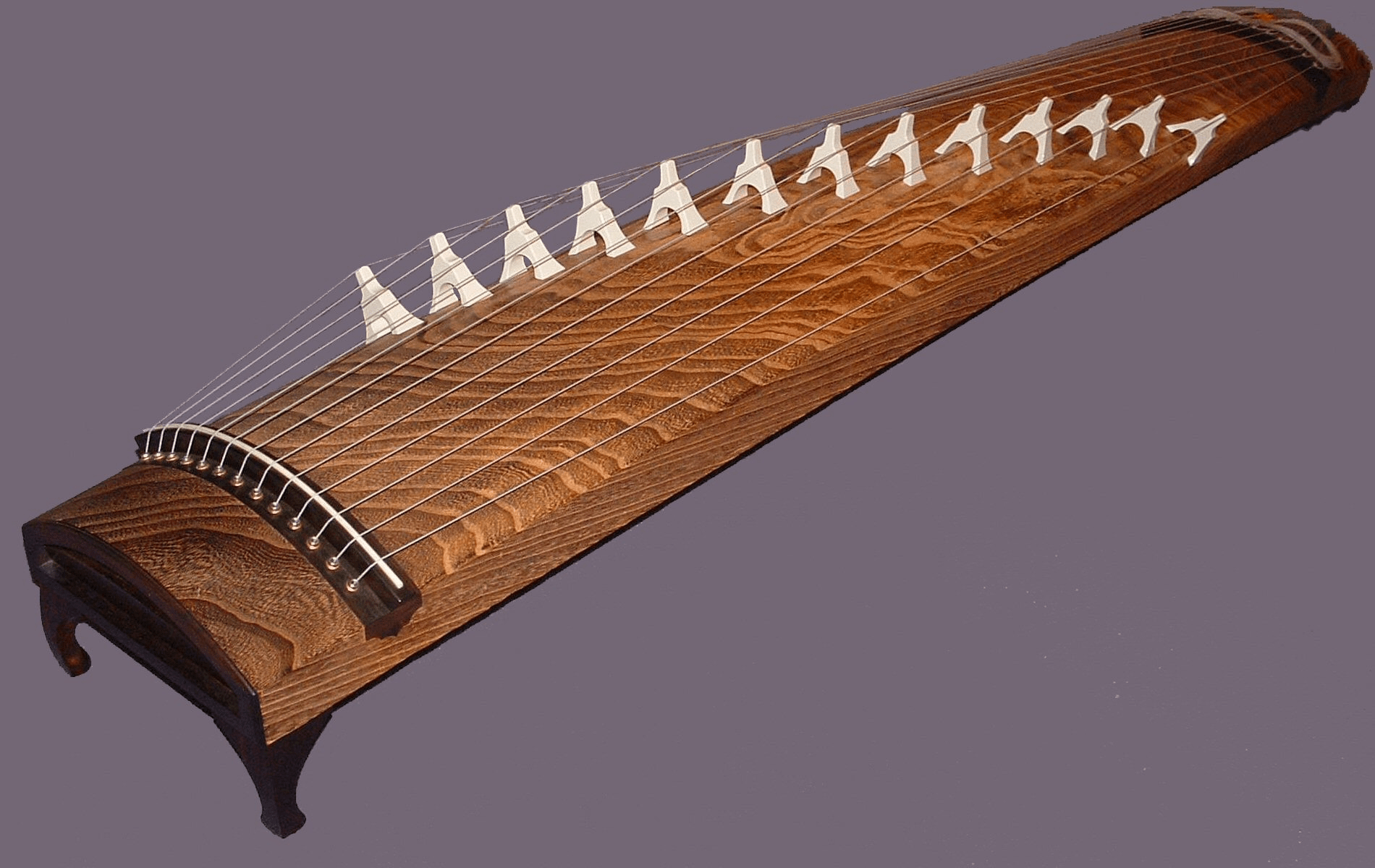

One example is the band Hiroshima. Formed by Dan and June Kuramoto in 1974 (and still active in 2022), the band expressed ethnic/racial pride by foregrounding the sounds of koto (Japanese zither), and often Japanese dance.

"Da Da," a track from Hiroshima's eponymous debut album (1979).

Japanese Koto, by Smgregory. CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Jazz in Asian American Music

Still other musicians, such as Mark Izu, Anthony Brown, Jon Jang, Francis Wong, Glenn Horiuchi and Fred Ho, found inspiration in free and avant-garde jazz. They saw this music's liberatory potential, and began collaborating with musicians from these traditions.

United Front was one of the most prominent mixed Asian American and African American combos in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

This is an excerpt of Outside in Sight: The Music of United Front (1986). Uploaded to Vimeo by Brenda Wong Aoki & Mark Izu.

Discussion

- Which track was most meaningful to you? Why?

In the last four slides, you heard four groups that include musicians involved in the Asian American movement. Based on listening to these tracks, discuss one or more of these questions in small groups or as a class:

- Do these tracks remind you of any music you listen to? Why (not)?

- Which track was least meaningful to you? Why?

- What do the musical sounds and/or lyrics of each track reveal about Asian American experiences?

- Are these tracks relevant to Asian American experiences today? Why (not)?

The Decline of the Asian American Movement

Many scholars argue the Asian American movement began to peter out in the late 1970s.

Over the past decade, and particularly since the rise of anti-Asian violence in 2020, many Asian Americans have called to a new Asian American movement--one that fits the very different and vastly expanded landscape of Asian America in the 21st century.

This does not mean that Asian American activism stopped.

"#Solidarity." Millions March in New York City, December 13, 2014, by Marcela McGreal. CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

Learning Checkpoint

- What are some examples of Asian American activism before the late 1960s?

- What was the Asian American movement? How and why is the movement still relevant today?

- How did musicians involved in the Asian American movement of the 1970s express their Asian American identity?

End of Path 1: Where will you go next?

Return to Pathway homepage:

Hear Us Out! Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and Their Music

Path 2

30+ minutes

Taiko and the Asian American Movement

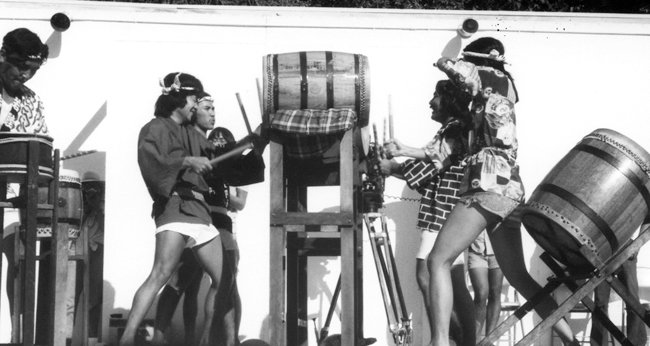

San Jose Taiko, by Bob Hsiang. Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

What is Taiko?

San Jose Taiko, by Bob Hsiang. Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

Taiko is the musical tradition that is most closely associated with the Asian American movement.

Taiko means "big drum" or "fat drum" in Japanese. Taiko drums are played using bachi, or cylindrical wooden sticks about 16 inches long and three-quarters of an inch in diameter.

What is Taiko?

New York City-based Soh Daiko performs one of the group's signature pieces, "Hachidan Uchi" ("Hitting Eight Sides") by Peter Wong and Jennifer Wada.

In North America, the term taiko generally refers to kumi-daiko: ensembles that use big and smaller drums, other percussion instruments, voice and choreography. Watch an example.

The Development of Taiko

Many drums used in contemporary taiko came from Buddhist and Shinto rituals, gagaku (court music), noh, and kabuki theater.

Although these instruments have existed for centuries, the tradition of performances that focus on an ensemble of drums did not emerge until the 1950s.

"Ama-No-Naru Tatsu-O Dai-Kagura"

Listen for the solos played by each drummer.

The Flourishing of Taiko in the U.S.

Over the past half century, the art of taiko has spread throughout the world.

Seiichi Tanaka, by Tom Pich. National Endowment for the Arts.

In the U.S., there were two taiko groups in the late 1960s. The number grew to 200 in 2000 and 464 in 2016!

Early History of Taiko in the U.S.

The three earliest taikos in the U.S. were:

- San Francisco Taiko Dojo (founded 1968)

- Kinnara Taiko (Los Angeles, founded 1969)

- San Jose Taiko (founded 1973)

Kinnara Taiko in the Early Years, unknown photographer. Photo courtesy of Kinnara Taiko.

Early History of Taiko in the U.S.

In this period (late 1960s–early 1970s), most taiko players were Japanese Americans who wanted to challenge the stereotype of the weak Asian who is unable to speak up for themselves.

The founding of these ensembles coincided with the emergence of the Asian American movement, and many early players were movement activists.

"Big Drum: Taiko in the United States." Uploaded by Japanese American National Museum.

San Jose Taiko's "Ei Ja Nai Ka?"

"Ei Ja Nai Ka?" performed at the 2015 San Jose Obon Festival. Uploaded by San Jose Taiko.

Other works in this Path show how taiko pieces often emphasize power, precision and rhythmic / choreographic complexity.

The piece that best shows the connection between U.S. taiko and the Asian American movement is "Ei Ja Nai Ka?" by San Jose Taiko co-founder P.J. Hirabayashi.

"Ei Ja Nai Ka?" is different. The focus is not virtuosity, but participation.

"Ei Ja Nai Ka?"

"San Jose Taiko performs Ei Ja Nai Ka (At-Home Instruments)." Uploaded by San Jose Taiko.

A key goal of the Asian American movement was the development of an Asian American consciousness/identity. This requires a good understanding of Asian American history.

"Ei Ja Nai Ka?" pays tribute to the Issei, the early Japanese American immigrants who worked in plantations, mines, and on railroad construction.

The Growth of Taiko in the U.S.

Established at the Buddhist Temple of Chicago in 1987, Kokyo Taiko has been one of the most prominent taikos in the midwest. Uploaded by TEDxYouth.

In the last quarter of the 20th century, community and Buddhist-church-sponsored taiko groups were formed across the country. The 1990s also saw the start of the collegiate taiko tradition.

This growth brought many non-Japanese Americans into taiko, which led to many changes in the taiko community.

Taiko and Japanese American Reparations

Taiko player and ethnomusicologist Deborah Wong wrote:

"Playing taiko has been one of the most joyful and fulfilling experiences I've ever had, but it is also interlaced with anger--and more than one kind of anger at that."

San Jose Taiko Performs at the 2014 Day of Remembrance. Courtesy of San Jose Taiko. Smithsonian Folklife Festival Blog.

Taiko and Japanese American Reparations

Taiko was one of the key sounds of this campaign.

San Jose Day of Remembrance Poster. Smithsonian Folklife Festival Blog.

One source of anger was Japanese American incarceration during WWII.

In the 1970s/80s, Japanese Americans and their allies campaigned for and ultimately received reparations from the U.S. government.

Taiko and Asian American Jazz

In the 1980s, taiko players in the U.S. increasingly began experimenting with putting their drums in a variety of musical contexts.

In 1987, Asian American jazz composer/pianist Jon Jang wrote Reparations Now!.

Excerpts from Jon Jang's Reparations Now! Uploaded by Asian Improv aRts.

Taiko in the 21st Century in the U.S.

In the 21st century, taiko has continued to grow around the country. One of the most important developments is the huge increase in non-Asian American participation.

Another is the growth of infrastructure (e.g., conferences, online spaces) that allows taiko groups to network with one another.

Attendees at the 2019 North American Taiko Conference in Portland, Oregon, photo by Ben Pachter.

Kenny Endo

"Spirit of Rice" by Kenny Endo, performed by Kenny Endo and Friends in 2015. Uploaded by Taiko Center of the Pacific.

After playing in San Francisco Taiko Dojo and Kinnara Taiko, Endo trained in Japan and became the first non-Japanese national to receive "master’s rank" in classical Japanese drumming. He and his wife, taiko player Chizuko Endo, moved to Hawai'i in 1990, and built a strong taiko training program in the state.

One of the most important innovators in U.S. taiko is Kenny Endo.

Listening Reflection

In this Path, you have listened to at least four works involving taiko by Asian Americans:

- Peter Wong and Jennifer Wada: "Hachidan Uchi" (slide 39)

- P.J. Harabayashi: "Ei Ja Nai Ka?" (slide 44)

- Jon Jang: Excerpts from Reparations Now! (slide 50)

- Kenny Endo: "Spirit of Rice" (slide 52)

How are these works similar and different: musically, expressively, and socially?

Which performance speaks to you most/least? Why?

What other musical practices does taiko remind you of? Why?

Taiko and Gender

"Taiko is not a matter of Asian American women 'rediscovering' a certain kind of Asian body but is rather an intricate process of exploring a Japanese bodily aesthetic and refashioning/re-embodying its potential for Asian American women."

Tiffany Tamaribuchi in 1988, by Katherine Saunders.

Interestingly, around two-thirds of taiko players in the United States are women. In exploring the prevalence of Asian American women in this musical practice, Deborah Wong wrote:

Taiko Leadership and Gender

With its emphasis on power, large gestures and stances that command large personal spaces, taiko empowers Asian American women and allows them to "disown" both the Western stereotype of the passive sexualized Asian woman and the gender expectations of many Asian cultures.

"The Genki Spark Documentary Trailer", uploaded Misako Ono.

Despite their prevalence in the genre, however, women are often overlooked for leadership positions, and left out of taiko histories.

Taiko Reception in the U.S.

For example, "Ei Ja Nai Ka?" discusses long history of Japanese America and the community's many contributions to the U.S.

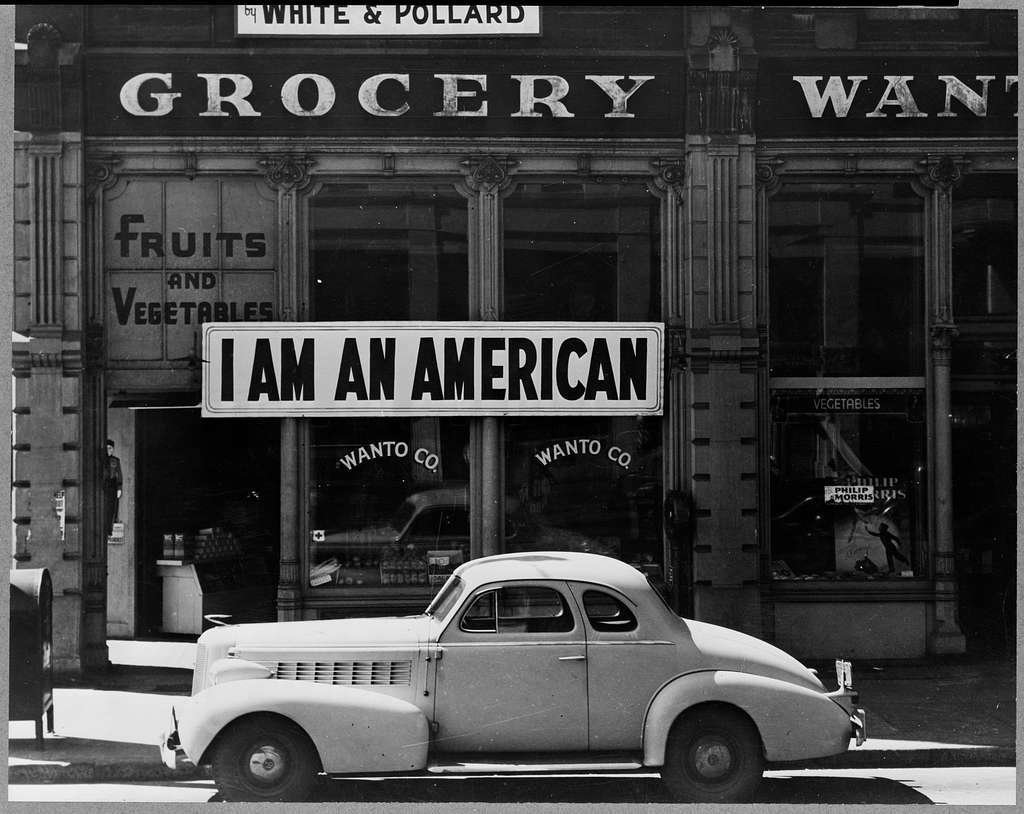

The Wanto Co. Store in Oakland, California, by Dorothea Lange. Public Domain {{PD-USGov}}, National Archives.

As we have seen in this Path, taiko performers in the U.S. often work hard to dispel stereotypes of Asians.

Taiko Reception in the U.S.

Despite these efforts, many audience members fail to understand what taiko players are trying to communicate because they still listen and watch with an Orientalist frame.

Sometimes, taiko reinforces pre-conceived notions that Asian Americans are "exotic" and "inscrutable".

Broken Communication, by Jack Moreh. Stockvault.

So ... How Do We Move Forward?

Deborah Wong wrote: "Taiko effectively addresses Asian American needs for empowerment precisely because it is commodified, mediated, and easily appropriated...Taiko teeters permanently on the edge of orientalist reabsorption...Its slipperiness as a sign of authenticity is both its power and a vulnerability"

What are your ideas for better communication between players and audience members?

Overcoming Barriers, by Jack Moreh. Stockvault.

Learning Checkpoint

- What is taiko and kumi-daiko? (describe musical characteristics, expressive qualities, social context)

- When and why did taiko become established in the U.S.? How is the early history of taiko connected to the Asian American movement?

- How has taiko in the U.S. changed since the 1970s?

- What are some challenges that the taiko community faces?

End of Path 2: Where will you go next?

Return to Pathway homepage:

Hear Us Out! Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and Their Music

Researching Asian American Arts

Path 3

15+ minutes

Nancy Wang and Robert Kikuchi-Yngojo, .

Arts and Social Justice Movements

As we have seen in Paths 1 and 2, the arts can play a major role in sustaining social justice movements.

This is because the arts are very good at storytelling, and reaching an audience beyond the activist community. Through theater, film, music, dance and the visual arts, audiences can build communities, learn, and forge possible paths toward a better future in an entertaining way.

In 1981, Nancy Wang and Robert Kikuchi-Yngojo founded Eth-No-Tec, an interdisciplinary story theater company based in San Francisco.

Project: Researching Asian American Arts Groups

In this project, you will do some research on a major Asian American arts group.

Here are some possibilities:

- Kearny Street Workshop

- East West Players

- Asian Improv aRts (AIR)

- Pan-Asian Repertory Theater

- Chen Dance Company

- Visual Communications

- Center for Asian American Media

- The Taiko Community Alliance (TCA)

- Theater Mu

Discover, by Mohamed Hassan. {PD}, via Pxhere.com.

The Project

In small groups, you will do research on your chosen organization. Try to find answers to the following questions:

- When, why, and by whom was this organization founded?

- What does this organization do (in the past and currently)?

- How has the organization changed over the years?

- Find a few seminal achievements for this organization. Why are they considered important? See if you can find relevant videos, audio recordings, newspaper reviews and reliable blogs about these seminal moments.

-

Does this group have a social justice mission?

- If so, what type is it? Is it implicit or explicit? How well does the group fulfill it?

- If not, why not?

Resources for the Project

To complete your research, you can:

- Explore the organization's website carefully.

- Go to https://archive.org, and see if there are archived version of the organization's website.

- Check out websites of local newspapers.

- Explore newspaper databases--many schools have subscriptions to newspapers.com or ProQuest. There is also a free trial available on newspapers.com.

- Search the Internet for relevant and reliable articles, videos and podcasts. Interviews are often particularly helpful.

Present Your Findings to the Class

- Why the organization was founded, and how it has changed since its founding;

- The key socio-political issues that the organization is most concerned about;

- If and how the organization has fought for social justice;

- What the organization's greatest achievements and challenges are.

After the completing your research, each group can give a 7-10 minute presentation in class. At the end of the presentation, your classmates should understand:

Reflection

After all the presentations, the class should discuss:

- How the organizations they studied are similar and different.

- How their achievements and challenges are similar and different.

- The potential and limitations of the arts in the fight for social justice.

Learning Checkpoint

-

How and why do the arts play an important role in sustaining social justice movements?

-

What were the most rewarding and most challenging aspects of this research project?

-

What are some of the achievements and challenges of the community-based arts organizations you learned about?

-

What resources are most useful when you research community arts institutions?

End of Path 3 and Lesson Hub 7: Where will you go next?

Continue to Lesson Hub 8:

Cultural Preservation and Adaptation: Kulintang, Kundiman, and Pinpeat in the U.S.

Lesson 7 Media Credits

© 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This project received Federal support from the Asian Pacific American Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 7 landing page.

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Video courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

\National Museum of American History

Images courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

South Asian American Digital Archive

Densho Encyclopedia

University of California Berkley Libraries

University of Southern California Libraries

Roz Payne Sixties Archive, University of Nebraska Lincoln

San Francisco State University

Labor Archives and Research Center, San Francisco State University

Asian Community Center Archive Group

National Archives

Smithsonian Asian Pacific America Center

Tom Pich

Smithsonian Folklife Festival

Kinnara Taiko

Bob Hsiang