Music of the Chicano Movement

Lesson Hub 1:

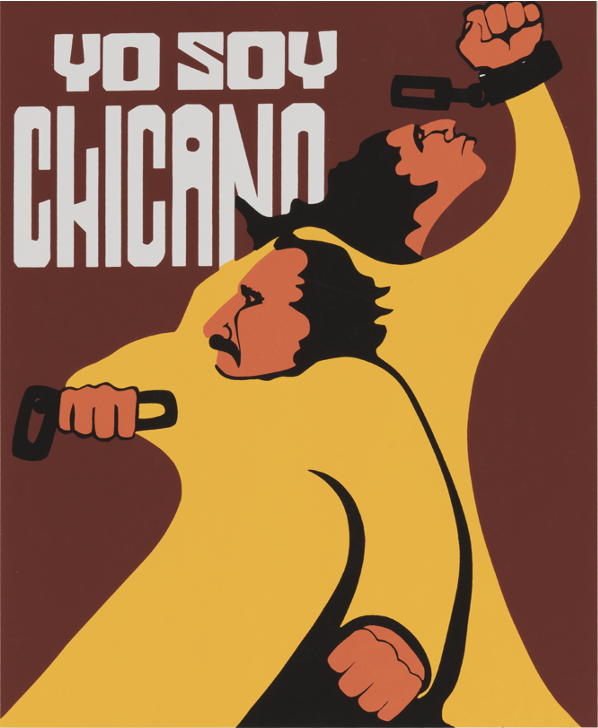

¡Yo soy Chicana/o!

Exploring Cultural Identity through Music

How is Chicana/o identity expressed through music?

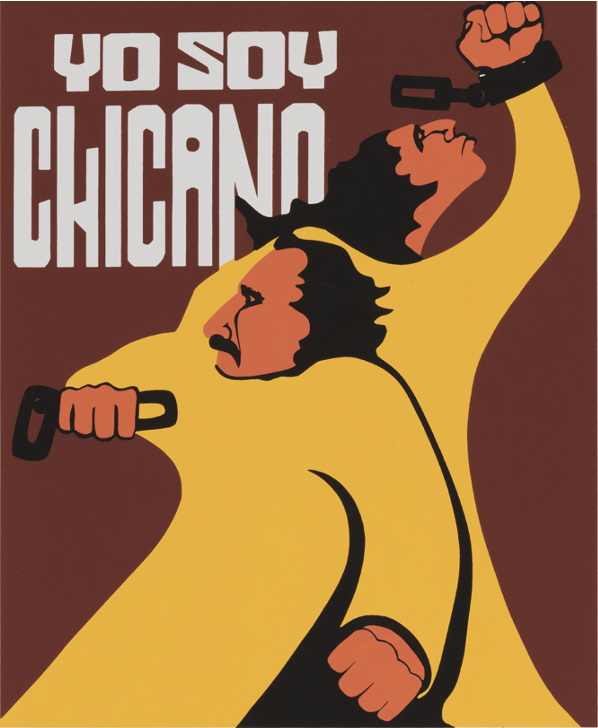

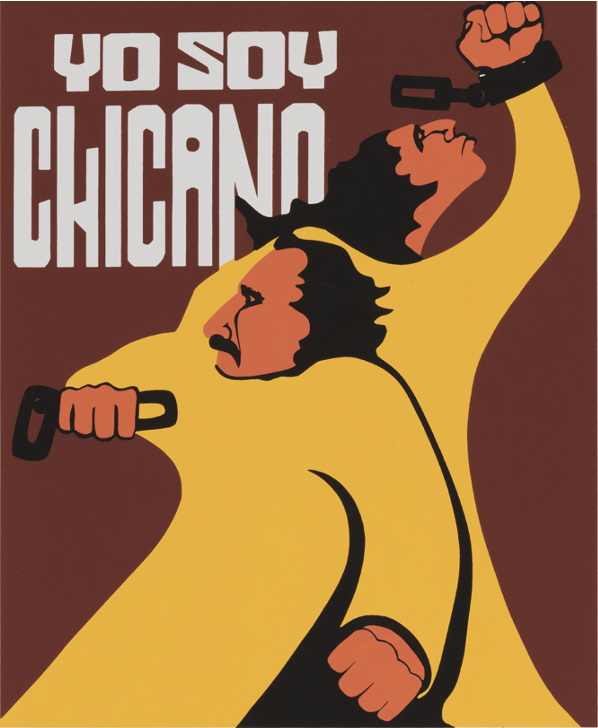

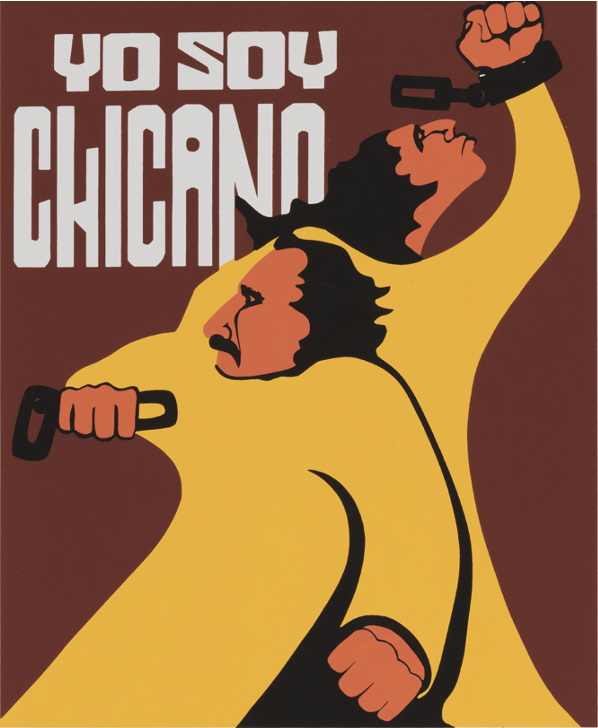

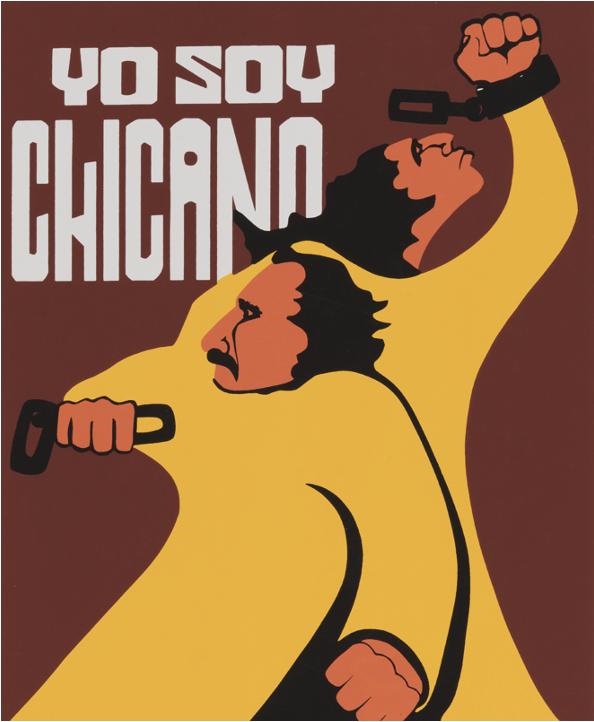

Yo soy Chicano, by Malaquías Montoya. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The overarching essential question for Lesson 1 is:

¡Yo soy Chicana/o! Exploring

Cultural Identity through Music

CREATIVE CONNECTIONS

HISTORY & CULTURE

MUSIC LISTENING

25 MIN

20+ MIN

30+ MIN

What Is Chicana/o?

Path 1

25 minutes

Chicano Pride Logo, designed by Custom Creations.

It’s complicated . . .

-

The term gained popularity in the late 1960s

-

It is associated with the Chicano movement

-

The term generally describes people with Mexican heritage living in the United States

-

However, this term’s true meaning is complex and deeply personal

What Is Chicana/o?

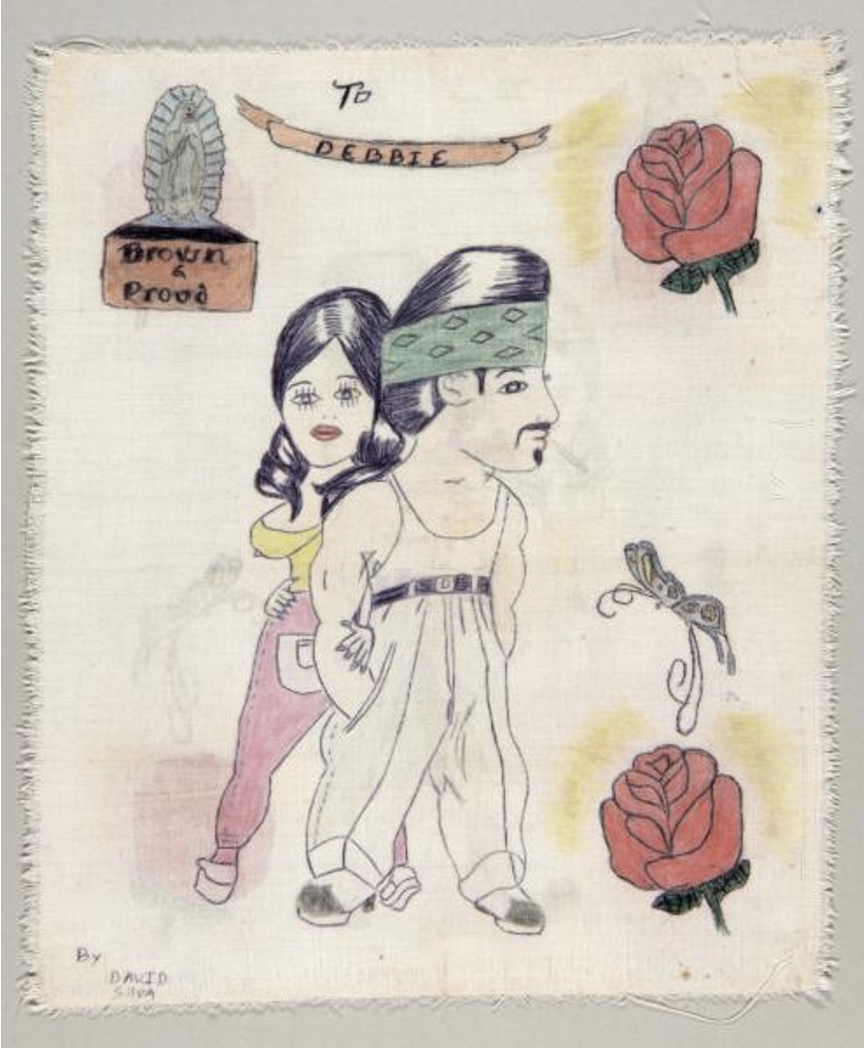

Chicana/o Pride

The term Chicana/o contributes to the formation and performance of individual and group identities.

It expresses feelings of pride about this element of cultural heritage.

Brown and Proud, by David Silva. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

For example, including Chicana/o in the title of this lesson highlights the inclusion of women in the Chicano movement.

Sometimes, people might use different letters, like Chican@ or Chicanx to include people of all genders in the movement.

Chicana/o Identity

Language is an important way to express identity choices.

Listening Activity: “Chicano”

- Listen to “Chicano,” performed by Rumel Fuentes and Los Pingüinos del Norte

- Follow along with the lyrics and fill in the blanks with the missing words

- Discussion:

What do these lyrics tell us about Chicana/o identity?

- Mexican heritage pride

- Brown and beautiful

- Not ashamed to be unique

- The desire to be heard

- Awareness of stereotypes/denigration/discrimination

- A feeling of unity/togetherness

Chicano Is . . .

Musical Sounds and Chicano Identity

- Play a short clip from the same recording (30-45 seconds)

- Discussion:

Where (geographically) do you think you might hear this?

"Border Music"

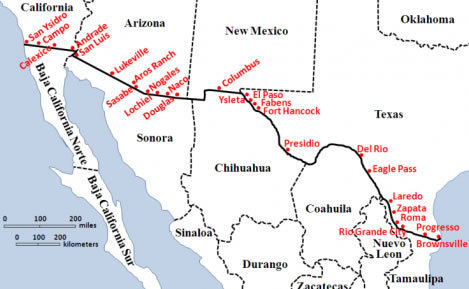

This type of music is most commonly heard along the Texas-Mexico border.

United States-Mexico Border Stations, by David Dilts. Family Search Wiki.

Música Norteña and Conjunto

A more specific term for accordion-based music on the Texas side of the border is conjunto.

Hohner Corona II, signed by Flaco Jiménez. National Museum of American History.

Música norteña, or music of the north, is an accordion-based genre that originated in northern Mexico.

Listen to the excerpt again.

What instruments do you hear besides the accordion?

In addition to the accordion . . .

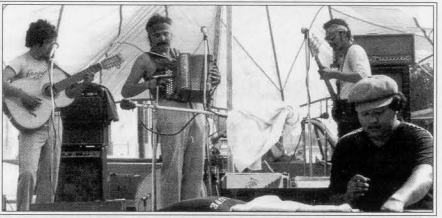

Los Pingüinos Del Norte 1970 (tololoche). Photo by Chris Strachwitz, Arhoolie Records.

This recording includes:

- Voice

- Steel-string guitar

- 12-steel-string guitar

- Tololoche (string bass, or contrabajo)

About the Performers

Left: Rumel Fuentes. Right: Los Pingüinos del Norte. Photos by Chris Strachwitz. Arhoolie Records.

Los Pingüinos del Norte was a música norteña ensemble from northern Mexico.

Rumel Fuentes was an important Mexican American singer/songwriter during the time of the Chicano movement (1960s–1970s).

This version of the song "Chicano" was recorded by Rumel Fuentes, with Los Pingüinos del Norte in 1976.

Watch Rumel Fuentes and Los Pingüinos del Norte playing "Chicano":

Chulas fronteras, by Les Blank and Chris Strachwitz. Les Blank Films.

Listen to another excerpt from "Chicano"

What do you notice about the language?

The language is unique because . . .

- The song is in English and Spanish; these languages are combined into a form known as "Spanglish"

- At the time the song was written, children in the southwestern United States were discouraged from speaking Spanish in school

- The song encourages listeners to appreciate AND celebrate their bilingualism

Chicana/o Identity

Discussion:

Why do you think some people in Mexican American communities have identified (and continue to identify) as Chicana/o?

The term Chicana/o . . .

- Is “a form of self-affirmation” (Montoya 2016, p. 5)

- Represents cultural awareness and ethnic pride

- Sometimes reflects a person’s willingness or desire to collectively combat discrimination, marginalization, oppression, and exploitation - issues that have historically plagued Mexican American communities

It's important to remember that . . .

Cultural identity is informed by personal choices:

We get a say in what descriptors define us and our identifications might change over time !

Learning Checkpoint

-

What does the term Chicana/o mean?

- What is the typical instrumentation for música norteña/conjunto?

End of Path 1! Where will you go next?

What Was the Chicano Movement?

Path 2

20+ minutes

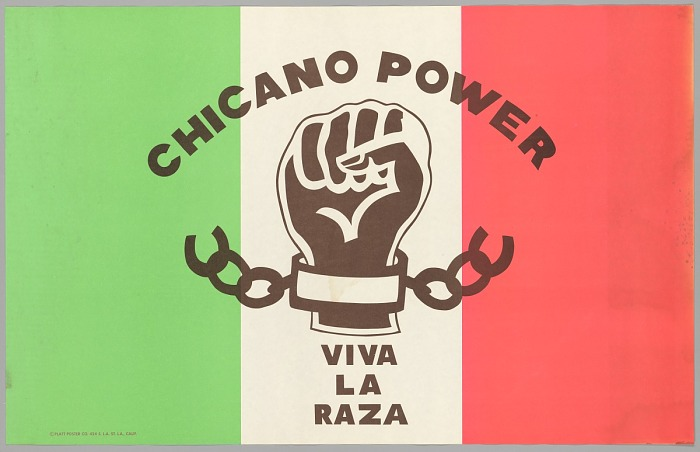

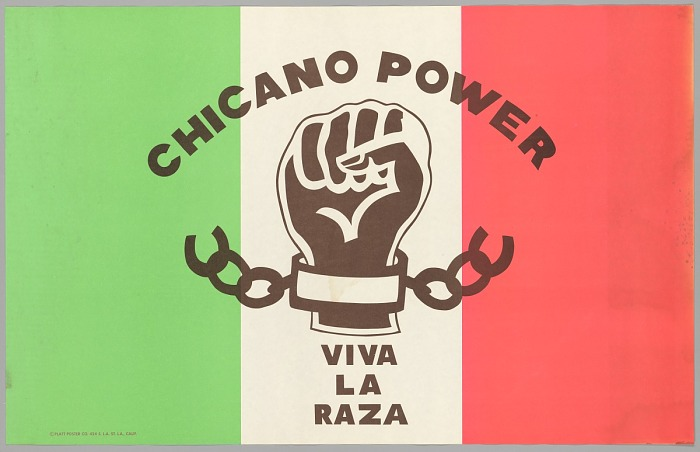

Poster with "Chicano Power" and "Viva la Raza" over a Mexican Flag, Platt Poster Company. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

What Was the Chicano Movement?

It can be understood as a collective response to issues of discrimination, oppression, and other injustices faced by Mexican American communities.

It is also known as the Mexican American civil rights movement or El Movimiento.

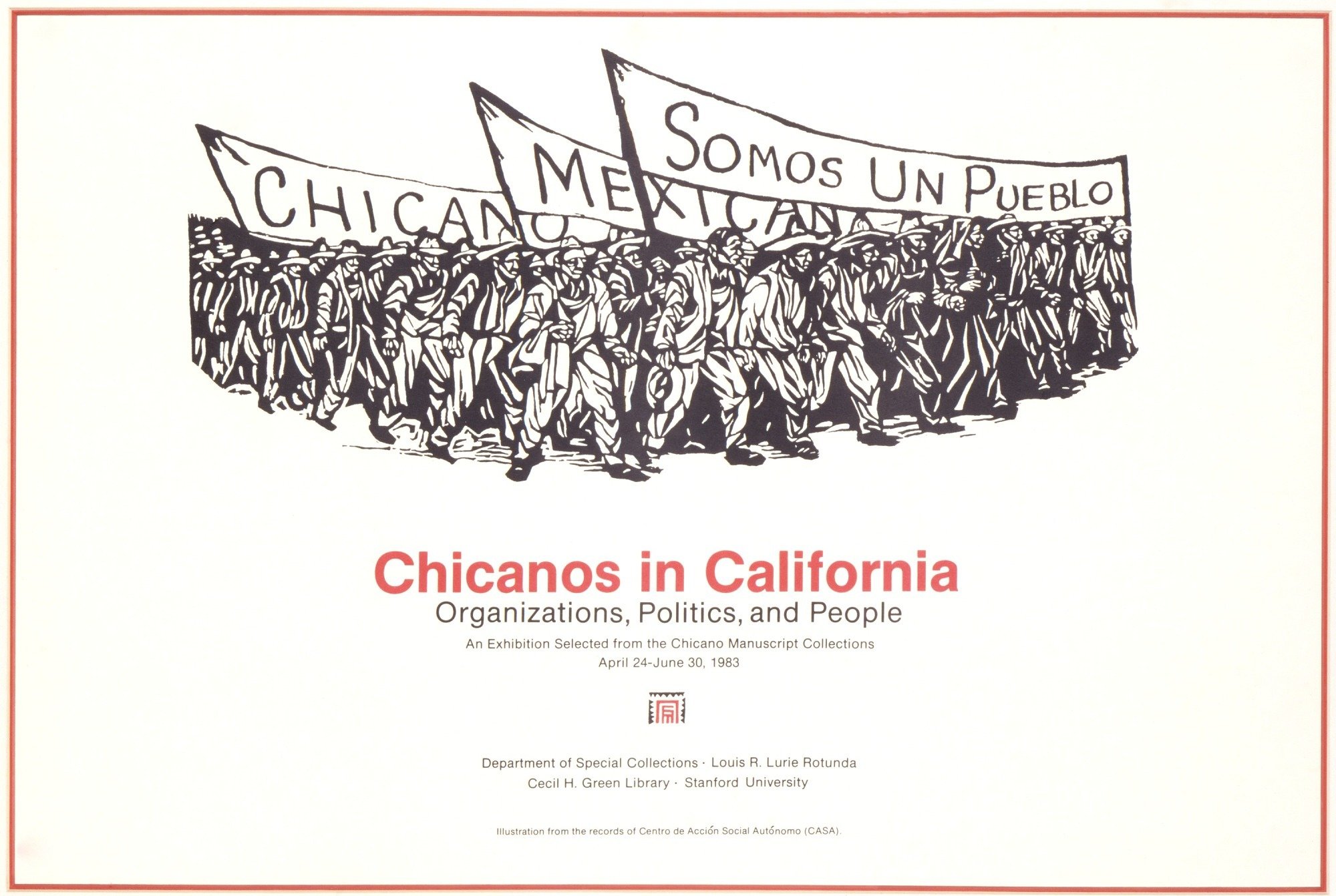

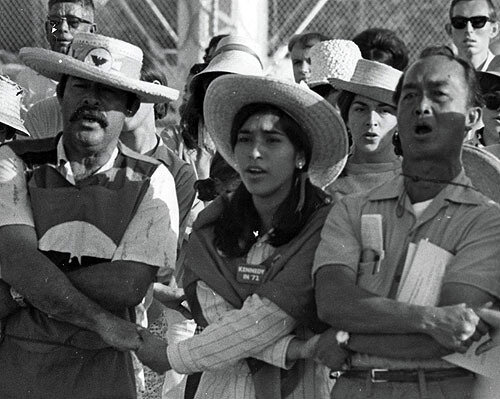

Chicanos in California, unknown artist. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The primary goal of the Chicano movement . . .

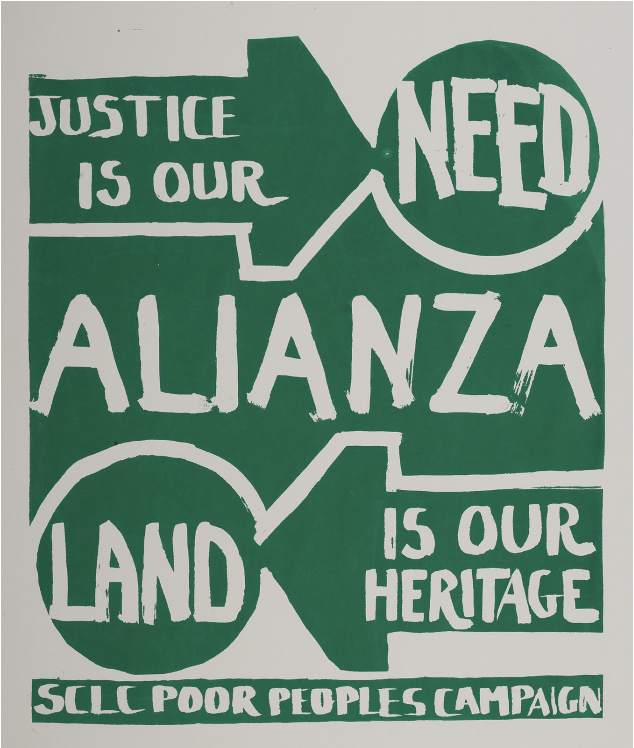

Southern Christian Leadership Conference Poor People's Campaign poster, Justice Is Our Need... unknown artist. National Museum of American History.

The Chicano movement . . .

- Took place during the late 1960s and 1970s

- Grew out of people’s awareness of continued oppression, exploitation, marginalization, and cultural disenfranchisement

During this time, people were ready to take social action to fight for justice and equal rights.

Listening Activity: “Yo soy tu hermano, yo soy Chicano”

-

Listen to “Yo soy tu hermano, yo soy Chicano” (I Am your Brother; I Am Chicano) by Conjunto Aztlan

-

Follow along with the lyrics/translation and circle or underline words that provide clues about why people felt like an "uprising was needed during the time of the Chicano movement

-

Discuss

Conjunto Aztlan, photo courtesy of Juan Tejeda. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Themes in "Yo soy tu hermano, yo soy Chicano”

“They steal lands [colonialism], they steal jobs [unemployment]; hunger and poverty [financial inequity]; they killed my brother over there in Vietnam [fallen Mexican American soldiers]; cops and rangers are disgraceful [police brutality] . . ."

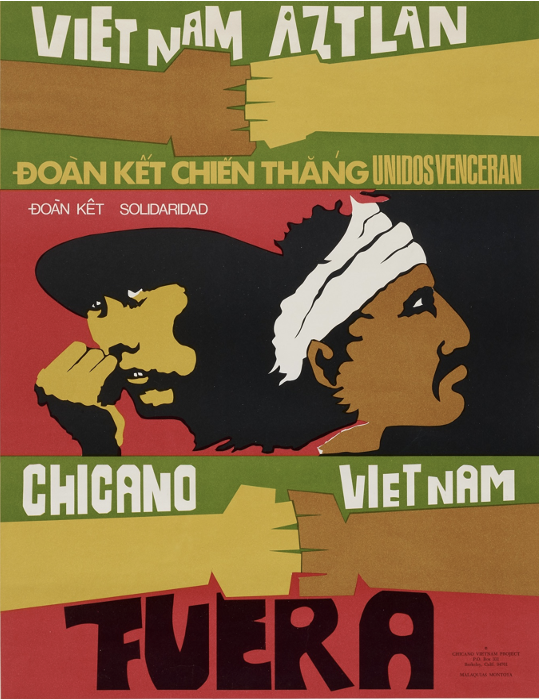

Vietnam/Aztlan, by Malaquías Montoya. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Optional Extension Activity: Issues and Images

In subsequent lessons you will learn more about specific goals of the Chicano movement. Three of these were: Rights for farm workers, restoration of land, and education reform.

-

Find and print historical photos from the 1960s–1970s that illustrate these goals.

-

Use the collected photos to create a class collage.

-

Alternatively, students can write a statement or skit based on characters developed from the images.

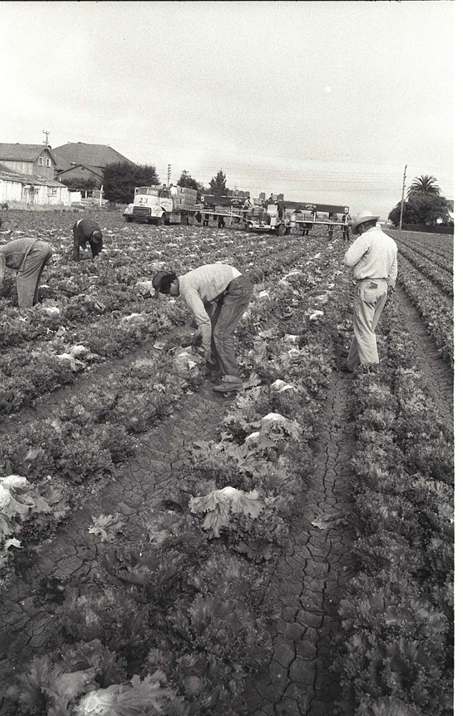

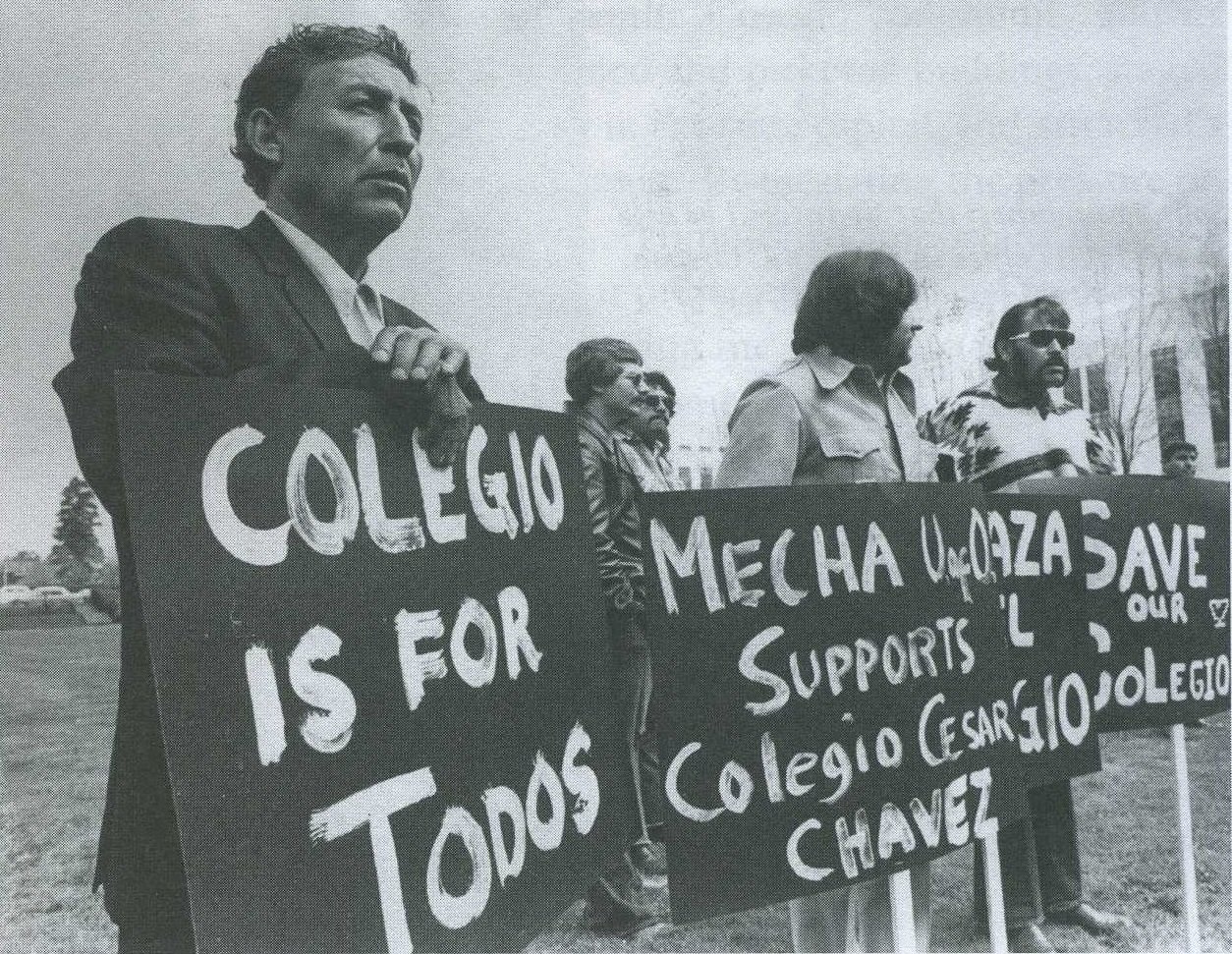

Above: Braceros Picking Lettuce, photo by Leonard Nadel. National Museum of American History.

Left: Resurrection City: Untitled, photo by Jill Freedman. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Right: Ayuda para Colegio Cesar Chavez, by user Movimiento. Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0).

Learning Checkpoint

What was the primary goal of the Chicano movement?

During the time of the Chicano movement, why did people feel like an “uprising” was needed?

End of Path 2! Where will you go next?

Exploring Cultural Identity through Music

Path 3

30+ minutes

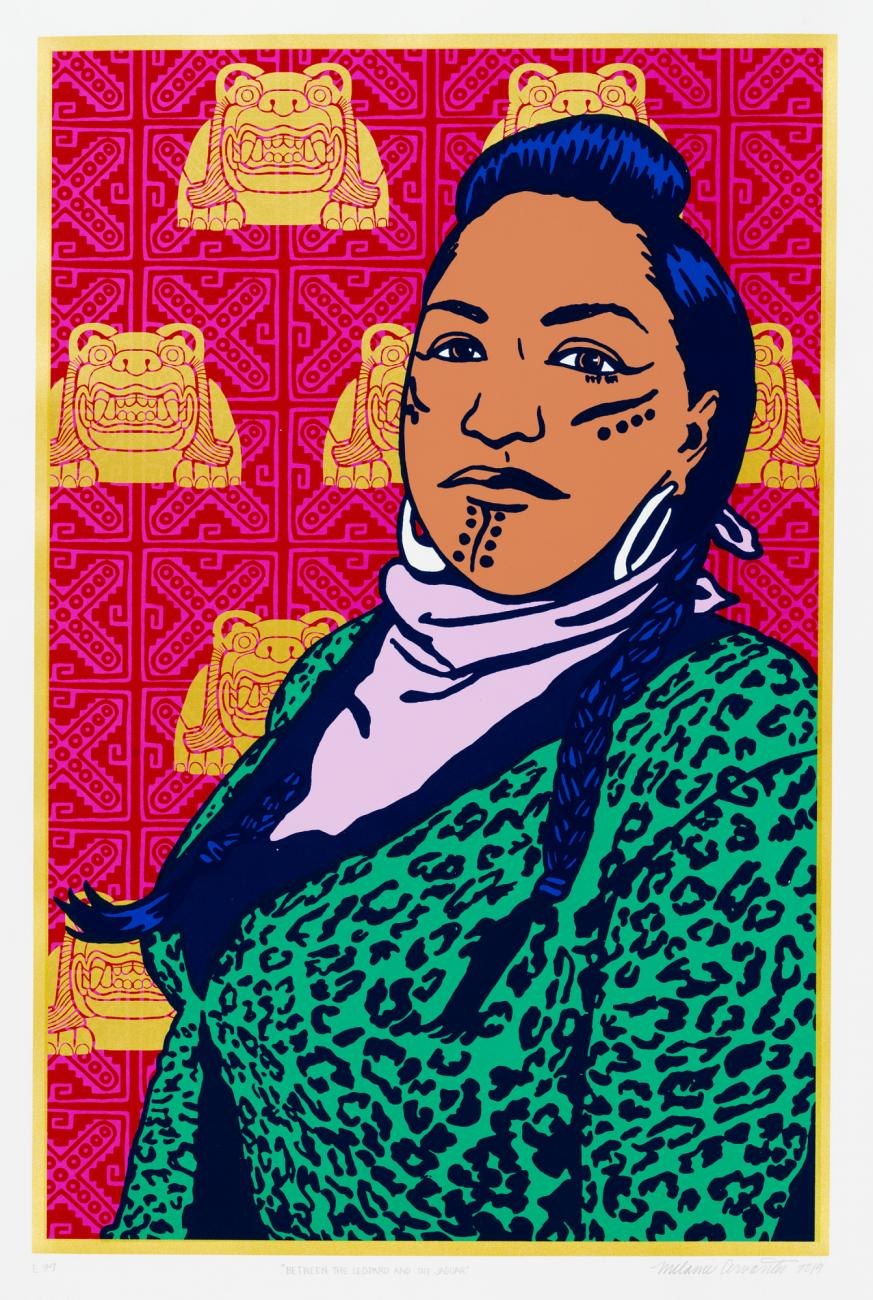

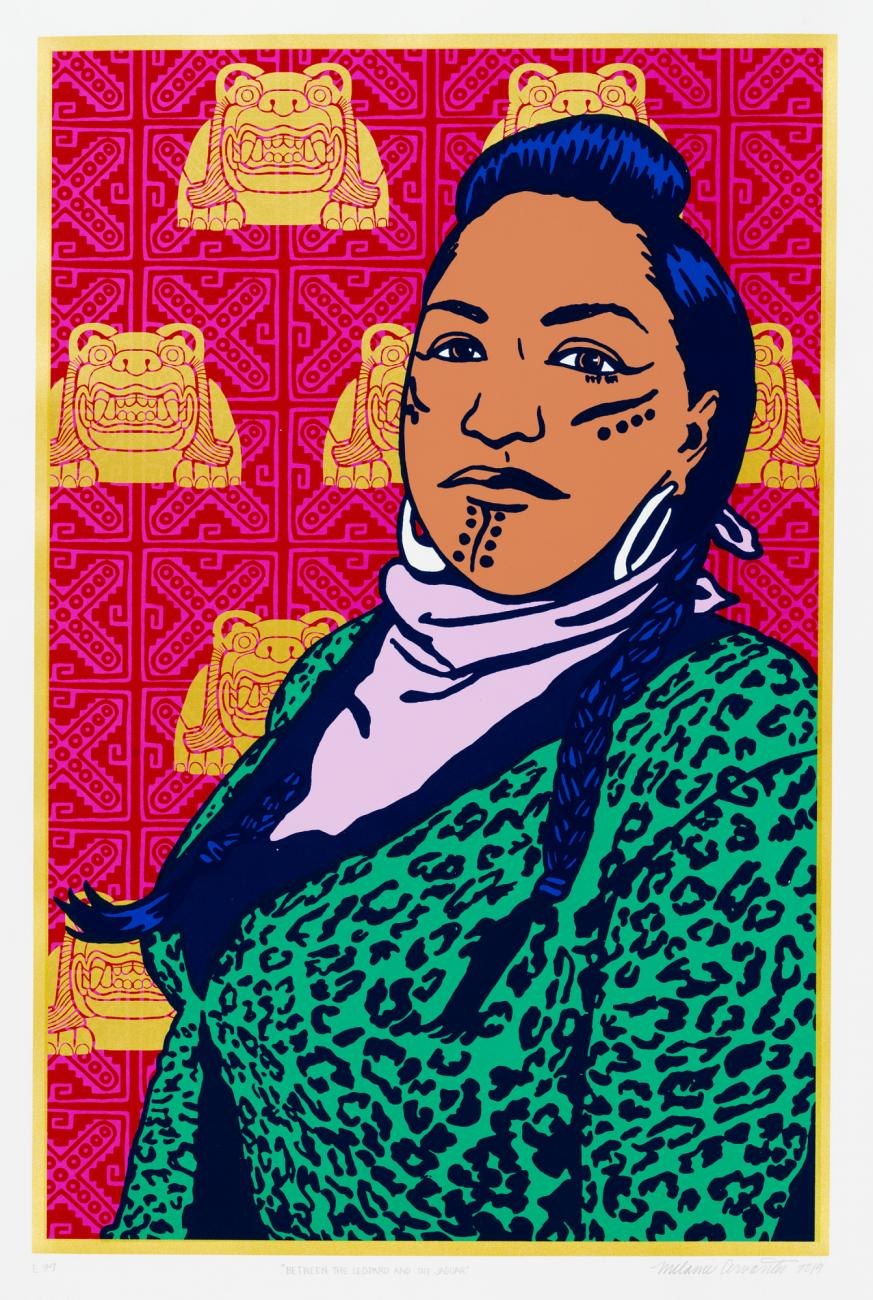

Between the Leopard and the Jaguar, by Melanie Cervantes. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

¡Yo soy Chicano!

The song we will focus on in this part of the lesson, “Yo soy Chicano,” was composed by a group called Los Alvarados as they travelled by bus to the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign, organized in Washington, DC.

This song became an anthem for Chicano movement activists.

Pinback Button, Poor People's Campaign, unknown artist. National Museum of American History.

What is an anthem?

Merriam-Webster defines anthem as:

“A rousing popular song that typifies or is identified with a particular subculture, movement, or point of view.”

Anthems:

• re-affirm ethnic or cultural pride

• serve as a symbol for a particular cultural group

• uplift and celebrate

Listening Activity: “Yo soy Chicano”

Which aspects of Chicana/o culture are celebrated in this song?

-

Listen to the song “Yo soy Chicano”, by Los Alvarados

-

Circle or underline lyrics that relate to this guiding question:

Chicano Pride Logo, designed by Custom Creations.

Themes in "Yo soy Chicano”

- Honor

- Pride

- Defense of the poor

- Valor/courage

- Community

- Brown color

- Masculinity/strength

- Heart

- Faith

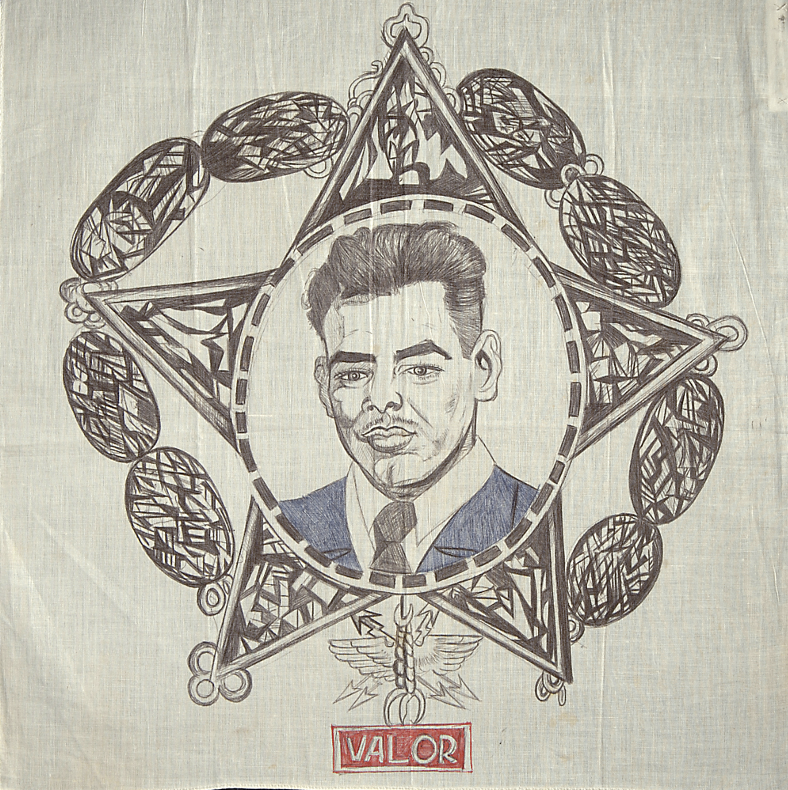

Valor paño, unknown artist. National Museum of American History.

Songs as Symbols

Protestors Singing on the Picket Line, photograph by Hub Segur. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

During the Chicano movement, certain songs, such as “Yo soy Chicano,” became powerful symbols for people who identified as Chicana/o.

Anthems unite people who work toward a common goal.

Cultural Identity Is Complex!

Everyone has multiple facets of cultural identity based on things like:

Race

Ethnicity

Geography

Language

Religion

Nationality

Gender

Profession

Neighborhood

Beliefs

Values

Age/Generation

Interests

Hobbies

Sports

Etc…

There Is No One Way to Be Chicana/o

-

Some people who identify as Chicano are from Nicaragua, El Salvador and other Latin American countries.

-

People without Latin American heritage took part in the Chicano movement (See Lesson 6 for more information on Filipino farm worker Larry Itliong).

-

Members of the Chicano community discuss and debate how to name and express their cultural identity.

Written language can express this debate. For example ...

There Is No One Way to Be Chicana/o

When spelled with an "x" . . . Xicano highlights Indigenous heritage in Mexican American culture.

Many Indigenous languages in Latin America pronounce "x" like "sh". . . . so Xicano is said like "Shicano."

There Is No One Way to Be Chicana/o

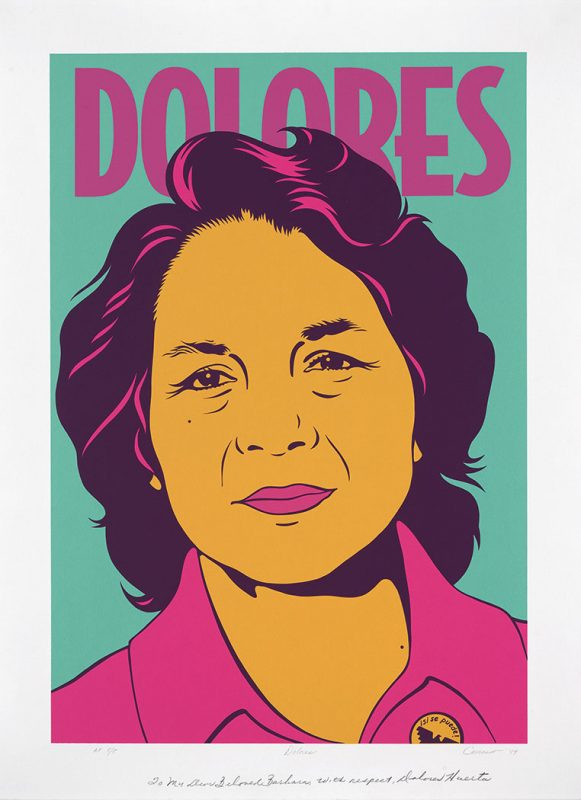

Chicana highlights the inclusion of women.

Dolores Huerta, by Barbara Carrasco. National Portrait Gallery.

There Is No One Way to Be Chicana/o

Chican@ acknowledges that culture is made by both men and women.

Quetzal, by Brian Cross. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

There Is No One Way to Be Chicana/o

Chicanx is a term that embraces all genders.

It leaves identity open to individual choice, current and future changes, and transformations.

Carlos Samaniego and Natalia Meléndez from Mariachi Arcoiris de Los Ángeles, by Daniel Sheehy. Smithsonian Folklife Magazine.

Creative Activity: Part One

Instructions: Place your name in the center and use the outside bubbles to name aspects that are important to defining who you are.

(Used with permission from Learning for Justice)

Complete the “My Multicultural Self” worksheet.

Exploring Cultural Identity through Music

Choose one of your identity bubbles to focus on…

Can you think of a song (anthem) that reflects this part of your cultural identity?

Creative Activity: Part Two

Complete the “Exploring Cultural Identity through Music” worksheet

Instructions:

- Write out the lyrics to the song you chose.

- Can you find a place in the lyrics that celebrates this facet of your identity?

- Can you find a statement in the lyrics that is inspiring, motivating, or uplifting?

- Write 2-3 sentences that describe why this song serves as a symbol of pride for this facet of your cultural identity.

Learning Checkpoint

- Why did certain songs become “anthems” for people who identified as Chicana/o during the Chicano movement?

- In what ways can music celebrate/re-affirm cultural identity and serve as a symbol of cultural pride?

End of Path 3 and Lesson Hub 1! Where will you go next?

Audio courtesy of:

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Video courtesy of:

Les Blank Films and Argot Productions

Images courtesy of:

Archives of American Art

The Arhoolie Foundation

Custom Creations

David Dilts

National Museum of African American History and Culture

National Museum of American History

National Portrait Gallery

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

TM/© 2021 the Cesar Chavez Foundation. www.chavezfoundation.org

Lesson Hub 1 Media Credits

© 2021 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information

This Lesson was funded in part by the Smithsonian Youth Access Grants Program with support from the Society for Ethnomusicology and the National Association for Music Education.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 1 landing page.