Listen What I Gotta Say: Women in the Blues

Lesson Hub 3

Melting Pot: Becoming the Blues

6th grade–8th grade

In what ways did the mixing of cultural influences (especially characteristics from African and European musical styles) affect the creation of the blues?

The Story of the Jubilee Singers, Unknown photographer. National Portrait Gallery.

The question to consider throughout this Lesson is:

Melting Pot: Becoming the Blues

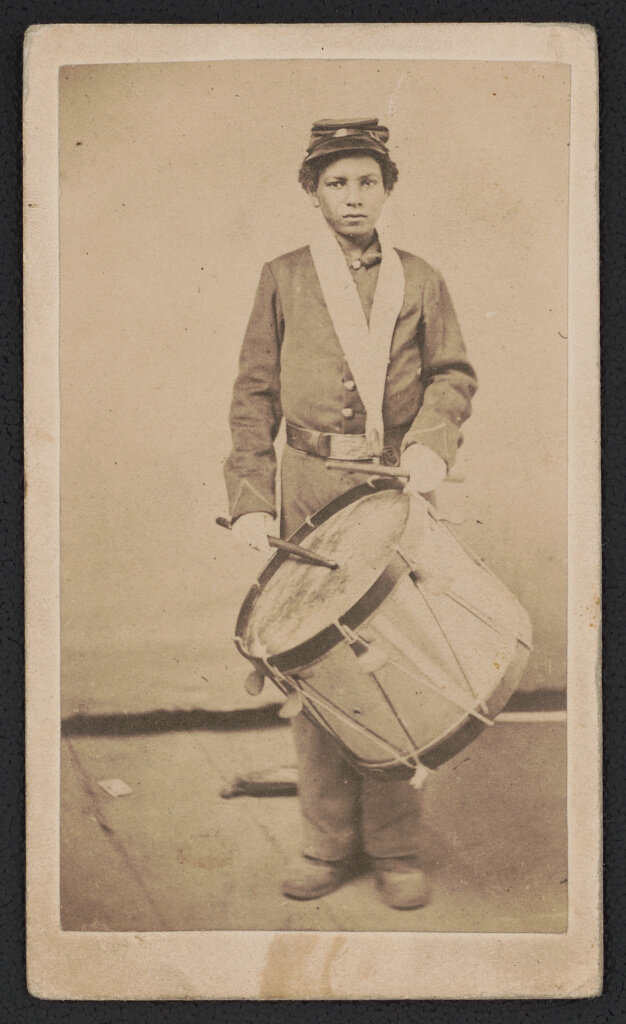

Taylor, young drummer boy for 78th Colored Troops (USCT) Infantry, in uniform with drum, Unknown Artist. Library of Congress.

Before the Blues: Spirituals

Path 1

20+ minutes

Fisk Jubilee Singers, Unknown photographer. National Portrait Gallery.

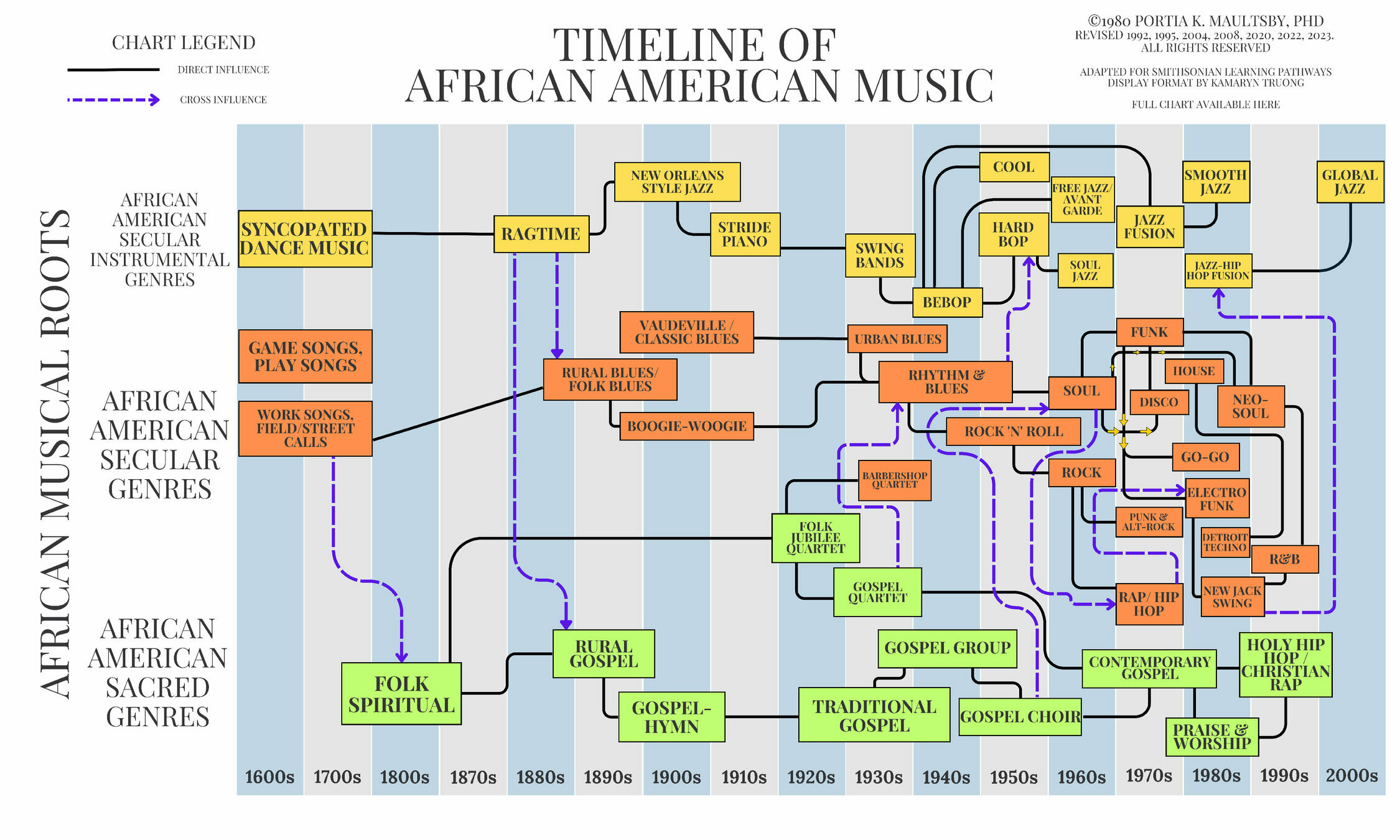

The Melting Pot of American Music

From the 16th-19th centuries, millions of people from Africa were forced from their homes and families and taken to the Americas.

While in the Americas, enslaved people from Africa began to blend their music cultures with the new music cultures they encountered.

Melting Pot: Becoming the Blues

Over time, new musical forms emerged (e.g., ring shouts, field hollers, work songs, spirituals, gospel, ragtime, blues, etc.)

Because this process happened over centuries, it is difficult to identify exactly which musical practices were of African origin, local, Indigenous, or European influence.

Attentive Listening

Listen to a short excerpt (30-45 seconds) from this audio recording.

As you listen, think about this guiding question:

What kind of music is this?

"Rock Chariot, I Told You to Rock," performed by Rich Amerson with Earthy Anne and Price Coleman.

Spirituals

This song, entitled “Rock Chariot, I Told You to Rock,” is an example of an African American spiritual.

This version was recorded in the 1950s in rural Alabama by Rich Amerson with Earthy Anne and Price Coleman.

Road Leading To Small Cabin, Alabama, photo by Harold Courlander. Folkways Records.

Attentive Listening

Listen again. Consider this question:

Why do you think people performed spirituals?

Spirituals: Religious Context

In the American South during the time of slavery, enslaved Black people had little mobility outside of the plantation and had little time for social activities as they worked from daybreak to sundown—except on Sundays and holidays.

On their Sundays, they developed a worship style independent of the white Protestant music tradition. They modified traditional Protestant hymns in ways that allowed them to express their frustrations and emotions.

These modified hymns are what we now call spirituals.

Spirituals: Secular Context

Although spirituals developed within a religious context, they were also quickly adapted for use while laboring in the fields to build community among enslaved workers.

Field Workers (Cotton Pickers), by Thomas Hart Benton. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

Attentive Listening: Rhythm

Listen to several additional short excerpts from the same recording (approx. 30-45 seconds each).

Each time you listen, think about a new guiding question:

What do you notice about the rhythm?

Generally Speaking .....

Rhythm: "Swing"

The lead singer begins the phrase before the downbeat.

This emphasis on the off-beat creates a “swing” feel.

“Swing” feel occurs when the beat is divided into two parts, and the former part is longer and more accented than the latter.

long

short

long

short

long

short

4

4

Generally Speaking .....

Attentive Listening: Form/Structure

What do you notice about the form/structure of this song?

Generally Speaking .....

Form / Structure: Call and Response

Listen again and pay attention to lyrics, which follow call-and-response form.

-

The male lead begins the phrase with the call, and the choir offers the response:

-

Lead/Call: Rock, Chariot, I told you to rock!

-

Chorus/Response: Judgement goin’ to find me!

-

Listen for the next calls. Try to sing along with the response.

Won't you rock, chariot in the middle of the air?

I wonder what chariot, comin' after me?

Rock, chariot, I told you to rock.

Generally Speaking .....

Attentive Listening: Style & Melody

What do you notice about the vocal style?

What do you notice about the melody?

Generally Speaking .....

Vocal Style & Melody

-

The singers use relaxed voices.

-

The singers use feeling in their singing.

-

The vocalists use bent pitches

Vocal Style

-

There is not a lot of variation

-

The range of pitches used is narrow

...anything else?

Melody

Spirituals before and after the Civil War

During the mid-19th century, spirituals were also used to relay coded messages about the Underground Railroad (e.g. “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”).

The Jubilee Singers (originated in 1871) is a vocal ensemble comprised of students from Fisk University (HBU in Nashville, TN).

After the Civil War, spirituals arranged for choir ensembles from historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) grew in popularity. These choirs toured the United States and Europe performing spirituals on the concert stage.

Optional: Listen to the Fisk Jubliee Singers!

The Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1875.

"Rockin' Jerusalem," performed by the Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1955

The Fisk Jubilee Singers 2012–13, by Bill Steber, CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

"Joshua Fit de Battle," performed by the Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1993

"Roll Jordan Roll," performed by the Fisk Jubilee Singers ca. 1913

Generally Speaking .....

A Musical Melting Pot

The spiritual is an example of a musical form that developed as Black Americans in the southern part of the country blended musical characteristics from various African traditions (e.g., swing, call and response, vocal styles) with European and local influences (e.g., choral music, hymns).

Over time, spirituals influenced the development of other musical genres created by Black Americans, such as gospel and the blues.

Generally Speaking .....

Spirituals and the Blues: Making Connections

Improvisation

Vocal Style

-

The performance style and lyrical content of spirituals can fluctuate depending on the performer. Verses can be added, rearranged, or left out.

-

Improvised singing and playing is common in the blues.

Form

- Call and response form is commonly present in spirituals due to its function in creating communal worship experiences.

- The use of call and response characterizes the musical relationship between the vocalist and instruments in blues music.

- Especially through ululations (a howling or wailing sound), spirituals express feelings and emotions, much like emotions are demonstrated in the blues.

Learning Checkpoint

- What are some common features of spirituals?

- How did spirituals influence the development of the blues?

End of Path 1: Where will you go next?

Combining Influences: Fife and Drum

Path 2

20+ minutes

Ed Young Southern Fife Drum Corps, by Diana Jo Davies. Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections.

Combining Influences: Fife and Drum

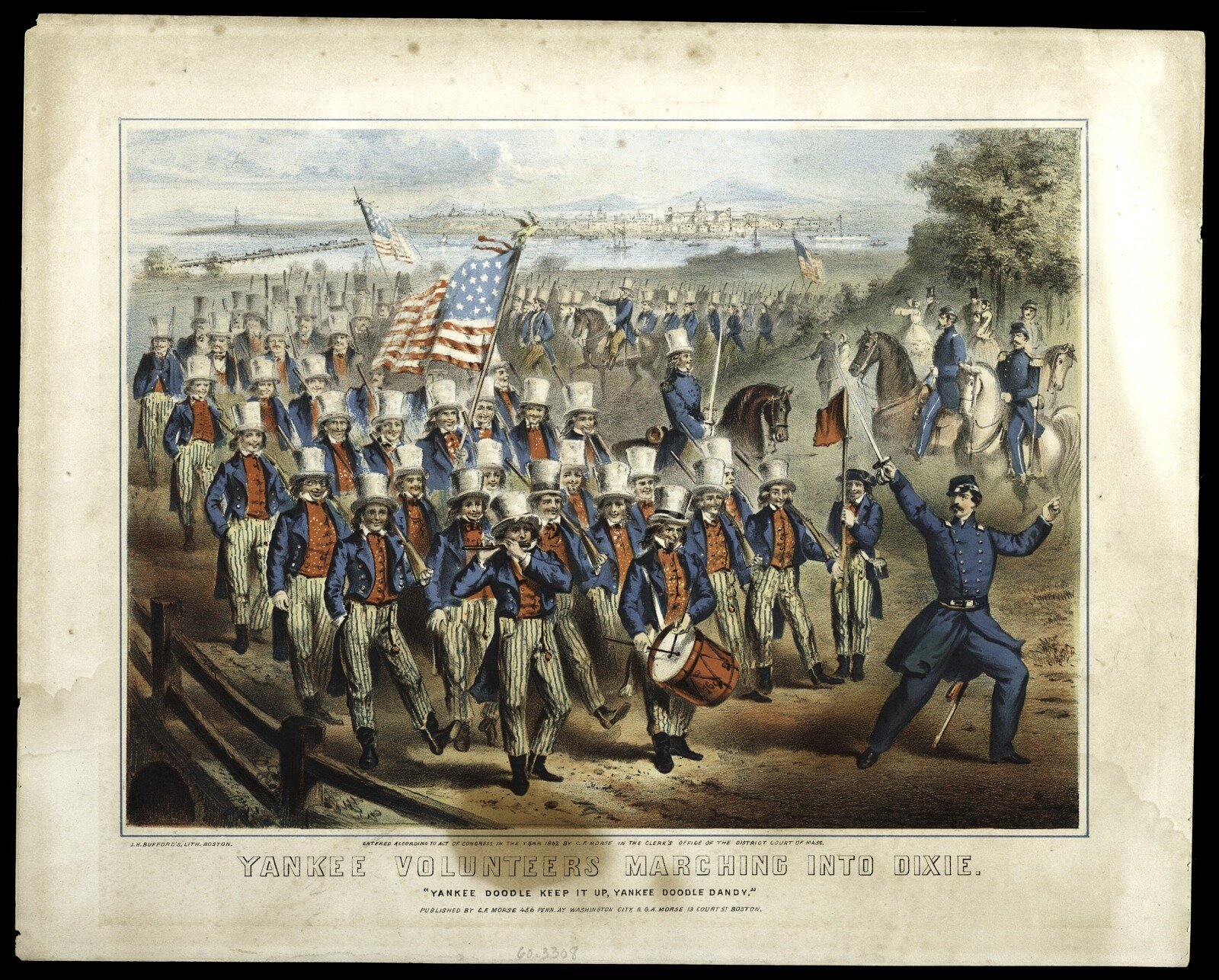

Yankee Volunteers Marching into Dixie in 1862, by John Henry Bufford. National Museum of American History.

The blues is like a sonic melting pot, incorporating a variety of cultural and musical influences from a variety of time periods.

One tradition that influenced the development of certain types of blues music was called fife and drum.

Fife and Drum: Historical Context

In colonial America during the 18th century, enslaved Africans were recruited to serve in the military (notably, during the Revolutionary War).

Enslaved people were not usually assigned to combat roles, as they were not trusted to bear arms. Instead, they were often enrolled in military bands, such as the fife and drum corps.

Fife and Drum Corps, Helwan, Egypt, photo by Helen Hamilton Gardener. National Museum of Natural History.

Fife as a Military Instrument

The practice of using fifes as a military signaling instrument is very old.

In 16th century Europe, fifes were used to signal commands on the battlefield, hours of duty, formations, and to lift morale.

The U.S. Army Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps, by Jacob N. Bailey. {{PD-USGov}}, via Wikimedia Commons.

Sounds of Fife and Drum

"France: Wine Dance Entrance," by Juan Oñatibia.

Listen for the sound of the fife and drums in these two audio examples. Both were recorded in Europe ca. 1940s–50s (Left: France; Right: Switzerland).

"March, A Drummer and Fifer," unknown musicians.

Fife and Drum in the American Military

The Fife and Drum Corps tradition continued in colonial America.

American Bicentennial: Fifer, United States Postal Service. National Postal Museum.

The use of a fifer on this commemorative stamp celebrating the country's 200th birthday shows the vital role this instrument played for the American military during the Revolutionary War.

After the Revolutionary War...

Unfortunately, white Americans continued to enslave Africans and their children, and drumming became prohibited.

Owners of enslaved people were fearful that enslaved Africans would use coded messages in their drumming patterns to incite rebellions and uprisings among other enslaved Africans.

The rhythms and detail patterns enslaved people learned within the fife and drum corps were not forgotten, however. Instead, they were transferred to other instruments that were permitted (e.g., guitars and body percussion).

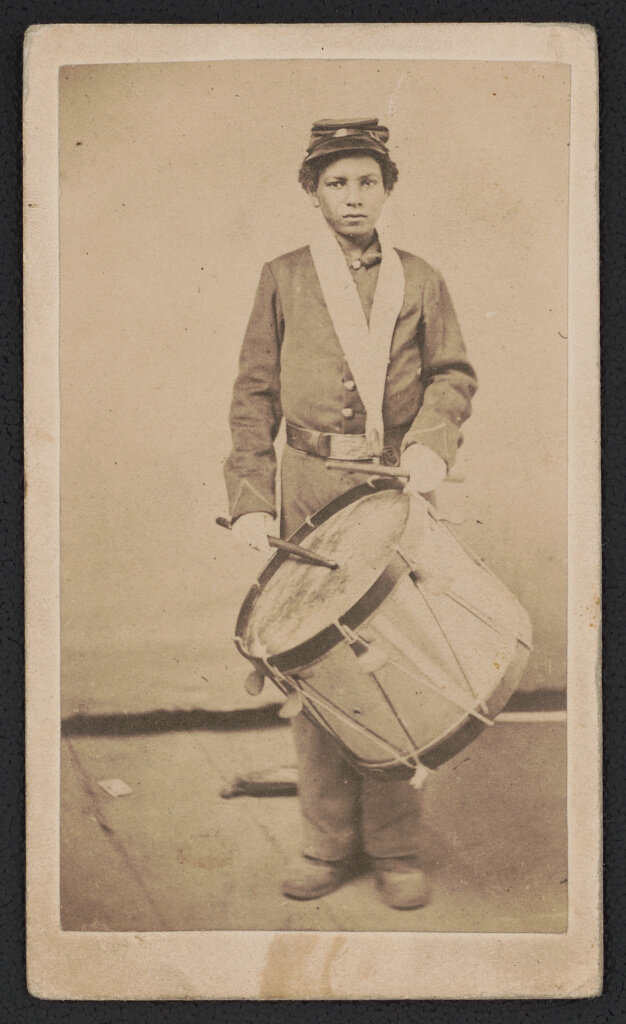

During the Civil War...

. . . enslaved Africans were once again recruited for fife and drum bands to aid soldiers.

After the Civil War (1865), fife and drum ensembles persisted in the American South, though no longer affiliated with battle.

Taylor, Young Drummer Boy for 78th Colored Troops (USCT) Infantry, in Uniform with Drum, unknown artist. Library of Congress.

After the Civil War: Musical Fusions

Once the Civil War was over, Black Americans took their knowledge from fife and drum bands and fused it with performance styles and practices familiar to them:

Union Regimental Drum Corps from the American Civil War, unknown artist. {{PD-US-expired}}, via Wikimedia Commons.

- improvisation

- interlocking patterns or polyrhythms

- blue notes

- call and response

- ululations

Fife and Drum Blues

The interesting combination of musical sounds that emerged in this situation became known as the Fife and Drum Blues.

Napoleon Strickland-Fife, Unidentified Girl-Bass Drum, and Otha Turne-snare drum, by Chris Strachwitz. Arhoolie Records.

Listen to an excerpt from “Shimmy She Wobble” by Napoleon Strickland with the Como Drum Band.

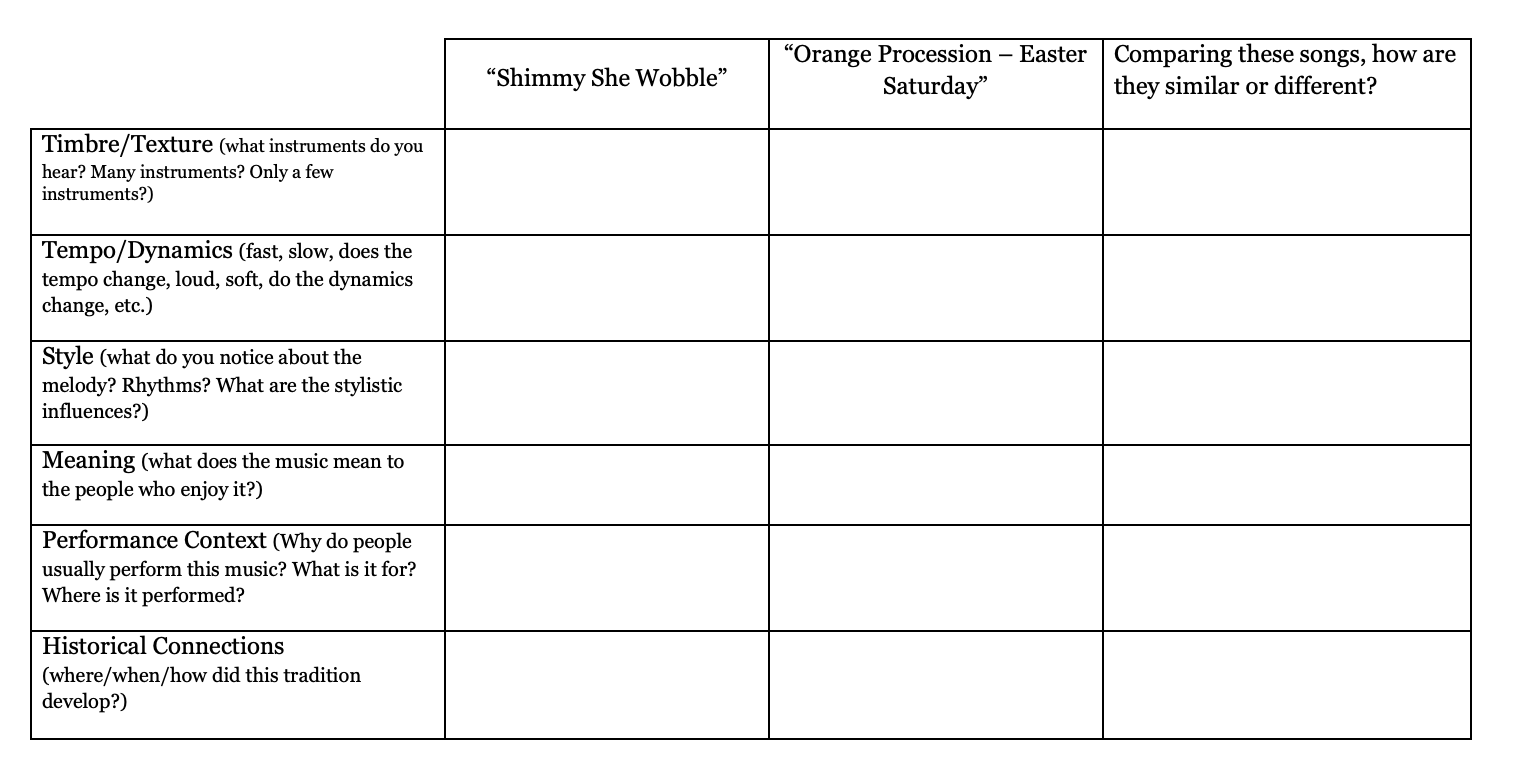

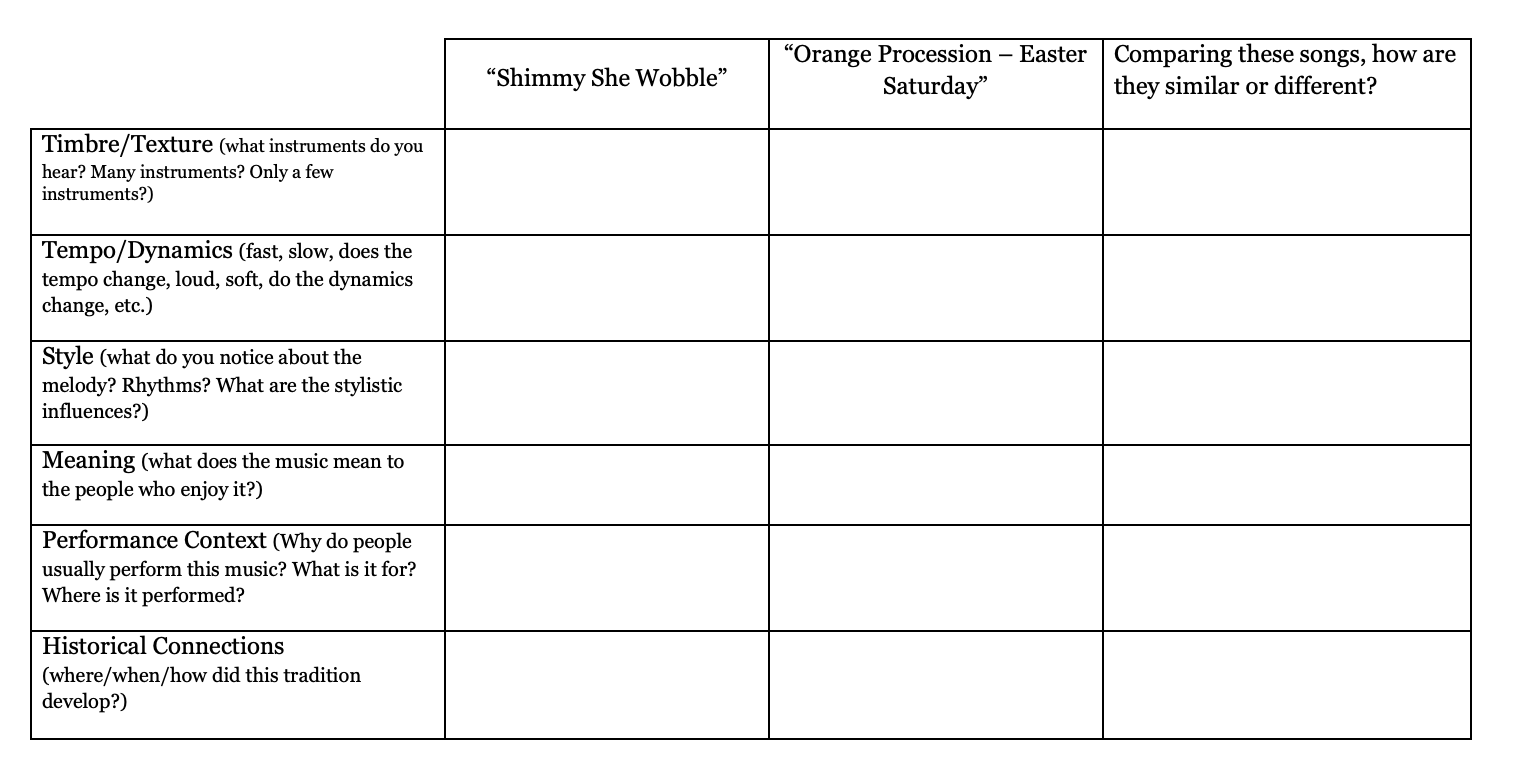

Listening Activity: Compare and Contrast

Listen to short excerpts from:

- “Shimmy She Wobble” by Napoleon Strickland with the Como Drum Band (Fife and Drum Blues)

- “Orange Procession - Easter Saturday” by the Orangemen of Ulster (Fife and Drum Corps from Northern Ireland)

As you listen, identify similarities and differences between these styles.

“Orange Procession - Easter Saturday”

“Shimmy She Wobble”

“Shimmy She Wobble”

“Orange Procession - Easter Saturday”

Discuss...

How are they different?

How are these pieces similar?

Do you hear any elements of the “blues” in “Shimmy She Wobble?”

“Orange Procession - Easter Saturday”

“Shimmy She Wobble”

“Shimmy She Wobble”

“Orange Procession - Easter Saturday”

Optional Extension Activity: Research

Are Fife and Drum Corps still around today?

If so, what role do they have in the military?

Learning Checkpoint

- What is the historical context of Fife and Drum Corps?

- How and why did the Fife and Drum Blues develop?

End of Path 2: Where will you go next?

Fife and Drum: A New Generation

Path 3

30+ minutes

The Rising Star Fife and Drum Band @ Blues Rules, by Christophe Losberger, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, via Flickr.

Watch this video...

As you watch, think about the following guiding questions:

Who are the performers?

What type of music are they playing?

Rising Star Fife & Drum Band, by Kelsey Michael, Marinna Guzy, Michael Headley, and David Barnes. Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.

Fife and Drum: A New Generation

- Fife and drum music arrived in America’s Deep South in the 18th century with military marching bands.

- The instruments (fife and drum) and elements of the style were woven into the musical traditions of enslaved Africans.

- Today, this tradition (which has influenced the blues) lives on in the work of Shardé Thomas who leads the Rising Star Fife and Drum Band.

Shardé Thomas at the 2012 Smithsonian Folklife Festival, video still provided by Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections.

Watch the video again (broken into several short excerpts). Each time you listen, discuss a new guiding question:

Attentive Listening

Which instruments do you hear?

What do you notice about Shardé’s singing style?

What do you notice about the song structure?

What do the lyrics mean?

Shardé Thomas

Shardé Thomas is the granddaughter of Otha Turner, the Mississippi fife master who founded the Rising Star Fife and Drum Band around 1907.

Connection: Otha Turner was one of the performers on “Shimmy She Wobble” (Lesson 3, Path 2).

About the Video

What do you notice about Shardé’s singing style?

Shardé’s vocal style resembles that of a blues singer

Which instruments do you hear?

Bass drum, snare drum, fife, and voice

What do the lyrics mean?

The lyrics are centered on feelings and share a narrative (similar to many blues songs)

What do you notice about the song structure?

The snare and bass drum parts seem to “interlock” (polyrhythm)

The song structure has some similarities to the blues (call and response).

1

2

3

4

Make Music!

Shardé Thomas learned to play the fife from her grandfather (Otha Turner) as a child.

In the next activity, you will have the opportunity to learn the melody and rhythm that she learned growing up!

- Start by listening to the beginning of the video several more times.

- When you are ready, hum or pat along.

Make Music!

Minor Pentatonic Scale

The melody you just heard primarily uses the d minor pentatonic scale (which is composed of five notes).

- Can you sing the minor pentatonic scale using a neutral syllable (like loo or la)?

- Can you sing the minor pentatonic scale using solfège (do, me, fa, sol, te)?

- Can you sing the d minor pentatonic scale using note names (d, f, g, a, c)?

D minor pentatonic scale

d

f

g

a

c

Play it on Instruments

Next, practice playing this minor pentatonic scale on an instrument:

- Keyboard, Orff instruments, ukulele, and/or a variety of wind instruments (especially flute or recorder) will work well for this activity

- Remember, the notes of this minor pentatonic scale are: d, f, g, a, c

D minor pentatonic scale

d

f

g

a

c

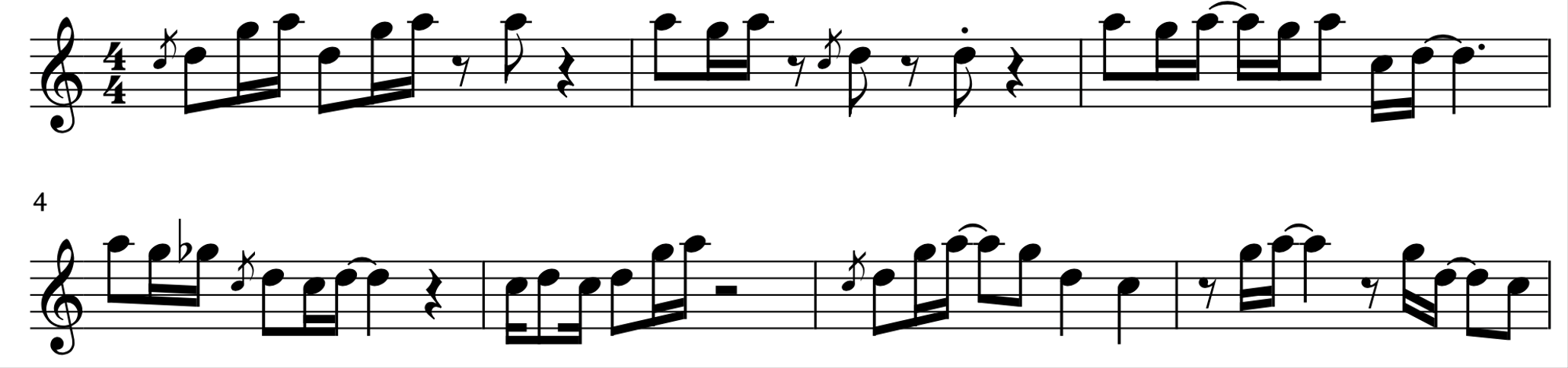

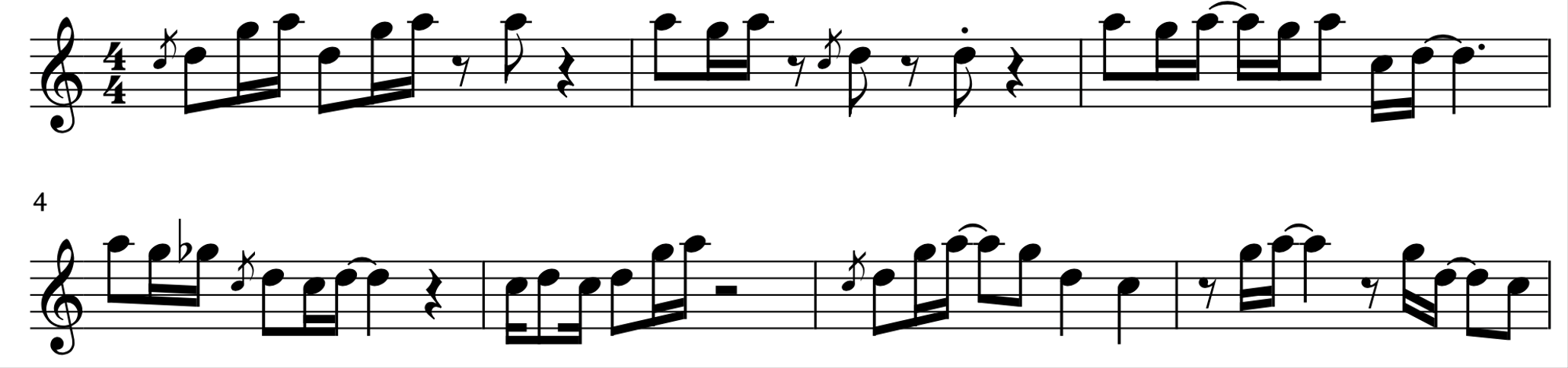

Enactive Listening (Playing without a Recording)

Next, you will learn this melody by ear on your instrument.

Transcription of Shardé Thomas's song, by Ayanna Heidelberg.

Learn the Rhythm

Next, you will learn an accompanying rhythmic ostinato pattern

-

When you are ready, play it on an instrument (drum, if possible)

4

4

Put it all together!

-

Some students can play the melody while others play the rhythm (you can also add a lower drum sound on the off-beats or another instrument on the steady beat).

-

Consider adding the grace notes and the accidental in measure 4 (especially if students are playing a wind instrument).

Optional Performance Activity

Did you know that many blues musicians use the minor pentatonic scale as they create improvised solos?

-

Practice using the notes in this scale to create your own “riffs” and/or improvised solos on your instrument.

D minor pentatonic scale

d

f

g

a

c

Optional Extension: Improvisation

Learning Checkpoint

- In what ways did Shardé Thomas’s performance resemble the blues?

- Why is the minor pentatonic scale useful when performing the blues?

End of Path 3 and Lesson Hub 3: Where will you go next?

Lesson 3 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Video courtesy of

Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage

Images courtesy of

The Arhoolie Foundation

National Museum of American History

National Museum of Natural History

National Portrait Gallery

Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

United States Postal Service

© 2025 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This Lesson was funded in part by the Grammy Museum Grant and the Smithsonian Youth Access Grants Program, with support from the Society for Ethnomusicology and the National Association for Music Education.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 3 landing page.