React

Redux

+

An introduction

@tkssharma

Obligatory Speaker Info

Tarun Sharma

Software Engineer

at @Srijan

i teach people

On the internet.

@tkssharma

Things I Like

-

Travelling :)

-

Learning how to write better code

-

And of course, JavaScript

Know your enemy

We covered what I like...

...but...

Things DON'T I Like

-

Duplicating code

-

Writing "framework" code

-

Debugging unhelpful errors

Duplicating Code

-

Copy/Paste code Feels Bad™

-

Reusability is the key

Including, nay, especially boilerplate

When we write composable code, it allows us to write something really well once, and reuse it as often as necessary.

"DRY code is the key to a happier, healthier life."

- Craig Burton, 2016

Writing "framework" code

-

Word.JS™ code

...with a little JavaScript mixed in

angular.module( "things", [] )

.controller( "SomeController", [ "$scope", "myService",

function( $scope, myService ){

$scope.someValue = "";

$scope.errorMsg = "";

$scope.formData = {};

myService.getThings().then(function(resp){

$scope.someValue = resp.data.someValue;

}).catch(function(resp){

$scope.errorMsg = resp.data.statusText;

});

});Almost entirely

framework

code

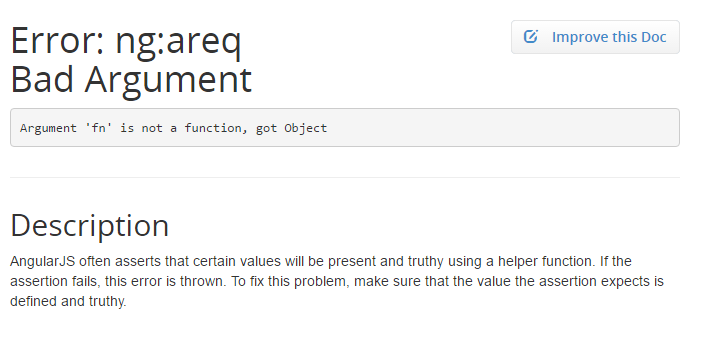

Debugging unhelpful errors

An actual Angular error:

angular.js:9899 Error: [ng:areq] Argument 'fn' is not a function, got Object

http://errors.angularjs.org/1.2.17/ng/areq?p0=fn&p1=not%20a%20function%2C%20got%20Object

at https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/angularjs/1.2.17/angular.js:78:12

at assertArg (https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/angularjs/1.2.17/angular.js:1471:11)

at assertArgFn (https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/angularjs/1.2.17/angular.js:1481:3)

at annotate (https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/angularjs/1.2.17/angular.js:3222:5)

at Object.invoke (https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/angularjs/1.2.17/angular.js:3876:21)

at https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/angularjs/1.2.17/angular.js:5605:43

at Array.forEach (native)

at forEach (https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/angularjs/1.2.17/angular.js:320:11)

at Object.<anonymous> (https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/angularjs/1.2.17/angular.js:5603:13)

at Object.invoke (https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/angularjs/1.2.17/angular.js:3899:17)A helpful link?

NOPE

React is a view framework, created by Facebook.

It was designed as a tool to facilitate rapid development, and deliver a high level of performance.

Hello, World

var HelloPage = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return (

<div className="jumbotron">

<div className="container">

<h1>Hello, React!</h1>

</div>

</div>

);

}

});Register a new component

Define a render function

...

Hey! That's not JS!

That is JSX, and it's pretty great.

Meet JSX

JSX is a JS syntax extension that looks a lot like HTML.

return (

<div className="jumbotron">

<div className="container">

<h1>Hello, React!</h1>

</div>

</div>

); return React.createElement(

"div",

{ className: "jumbotron" },

React.createElement(

"div",

{ className: "container" },

React.createElement(

"h1",

{ "class": "" },

"Hello, React!"

)

)

);There are a few minor differences between HTML and JSX markup. However, if you understand HTML, you'll grok JSX.

It isn't really JavaScript though. Browsers won't support it natively. So it will need to be preprocessed before you serve it to a user. There are several excellent tools for this.

But... Markup in my JS!?

Isn't that the opposite of "separation of concerns?"

<div ng-controller="SomeController">

<div ng-repeat="thing in things">

<h2>

{{ thing.title | uppercase }}

</h2>

<h3>

{{ thing.subtitle | uppercase }}

</h3>

</div>

</div>

angular.module('app')

.controller('SomeController',

function($scope, someService){

$scope.things = [ ... ]

});Consider:

Is there really any difference between having JavaScript in your markup and having markup in your JavaScript?

React acknowledges that the view model and the template are tightly coupled, and embraces it.

Cohesion

Everything about a component is in one place, including the template.

var HelloPage = React.createClass({

someMethod: function(){

/* do some stuff here */

},

render: function() {

return (

<div className="jumbotron">

<div className="container">

<h1>Hello, React!</h1>

</div>

</div>

);

}

});This encourages more fine-grained detail in how we separate out components.

Makes it easy to find relevant details about a component. There's only one place to look!

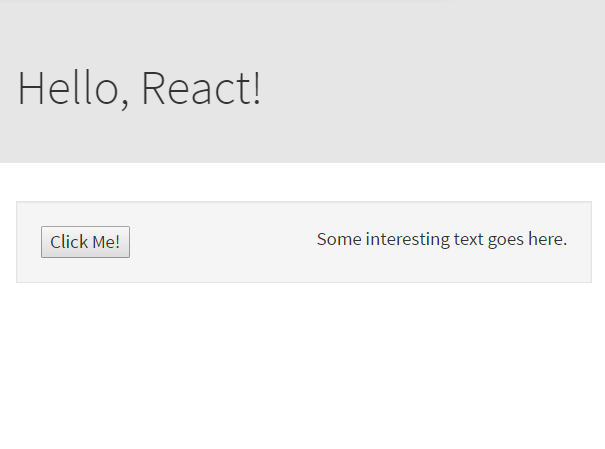

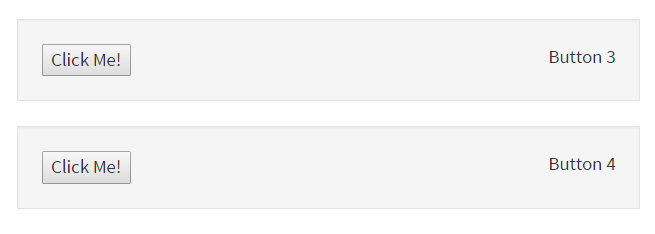

Our Example

var HelloPage = React.createClass({

doSomething: function(){

alert("You got it, boss!");

},

render: function() {

return (

<div>

<div className="jumbotron">

<div className="container">

<h1>Hello, React!</h1>

</div>

</div>

<div className="container">

<div className="well">

<button

onClick={this.doSomething}>

Click Me!

</button>

<p className="pull-right">

Some interesting text goes here.

</p>

</div>

</div>

</div>

);

}

});

ReactDOM.render(

<HelloPage />,

document.getElementById("app")

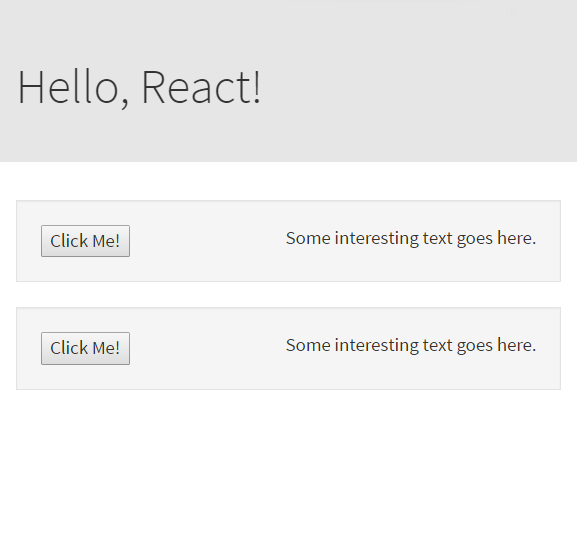

);Suddenly we need another button!

/* ... */

<div className="container">

<div className="well">

<button

onClick={this.doSomething}>

Click Me!

</button>

<p className="pull-right">

Some interesting text goes here.

</p>

</div>

</div>

<div className="container">

<div className="well">

<button

onClick={this.doSomething}>

Click Me!

</button>

<p className="pull-right">

Some interesting text goes here.

</p>

</div>

</div>

/* ... */

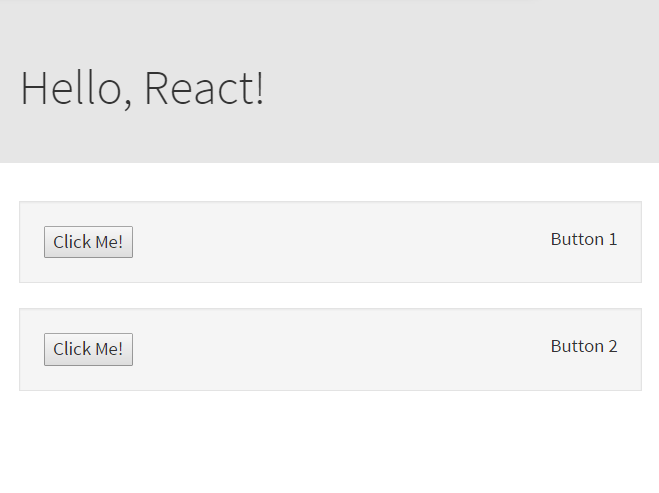

Composable Components

export default class FancyButton

extends React.Component {

render() {

const btn = this.props.btn;

return (

<div className="well">

<button onClick={

() => this.props.clickHandler(btn)

}>

Click Me!

</button>

<p className="pull-right">

Button { btn }

</p>

</div>

);

}

}import FancyButton from './fancyButton.jsx';

/* ... */(

<div className="container">

<FancyButton btn="1" clickHandler={ this.doSomething }/>

<FancyButton btn="2" clickHandler={ this.doSomething }/>

</div>

/* ... */)What are props?

let myData = this.props.data; <MyComponent data="A value" />"Props" are the properties you pass into a component. There are two main ways to do it.

<MyComponent data={ this.someData() } />Constant values like HTML attributes

Dynamic values between { }

In your consumer

In your component

Props are available on this.props

Remember our pain points

-

Duplicating code

-

Writing "framework" code

-

Debugging unhelpful errors

We already saw how we can keep our code duplication to a minimum by extracting out components.

Let's have a look at the other two:

Writing JS with just a pinch of React

render: function() {

const data = [3,4];

return (

<div>

<div className="container">

{

data.map(function(btn, index){

return

<FancyButton key={index} btn={btn}/>;

})

}

</div>

</div>

);

}React's small API surface area means more raw JavaScript and less React-specific code.

Here we're using a native JS array method to render multiple instances of a component.

The key prop is how React keeps track of the element for optimization. Every repeated element should have a unique key.

Useful error messages

Error: FancyButton is not defined(…)Let's say we forget to import FancyButton. Some frameworks would fail silently but React?

Even without source maps and other luxuries, it's not hard to find the offending line.

React.createElement(

'div',

{ className: 'container' },

data.map(function (btn, index) {

return React.createElement(FancyButton, { // ...

})

)React was designed to make web development faster and easier to do. Helpful errors contribute to this.

Redux is a predictable state container for JavaScript apps.

It was written by Dan Abramov for a conference talk called "Hot Reloading with Time Travel" in which he demonstrated time travel debugging.

Because state is deterministic, we can do really cool things, like rewind the application.

A pure function is one which, given the same input, will always produce the same output.

But first, pure functions

1 + 1 ->

function add(a, b){

return a + b;

}2

Using pure functions to manage our state makes our application deterministic. If we do the same things with the same data, we'll get the same result, every time.

To reduce in a functional programming sense is to apply a function to a set of values, passing data forward each time.

Reducing

let a = [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ];

const reducer = (total, next) => { return total + next };

a.reduce(reducer) // or a.reduce(reducer, 0)Notice that reducer is a pure function.

This will do 0 + 1, then 1 + 2, then 3 + 3, and so on.

To get started with Redux, you need a reducer function.

Reducers

A reducer function is a function which takes a state object, and an action, and returns a new state object.

function counter(state, action) {

if (typeof state === 'undefined') {

return 0

}

switch (action.type) {

case 'INCREMENT':

return state + 1

case 'DECREMENT':

return state - 1

default:

return state

}

}You must always return a state, even if you weren't given one. This is the initial state.

Actions have a type attribute so that you can update the state appropriately.

Now that we have a reducer function, we can create a store.

A store

That's all it takes. To start using the store, we dispatch an event.

var store = Redux.createStore(counter);

store.dispatch({ type: 'INCREMENT' });The store will then pass the current state, and the action into the reducer and replace the current state with the new one.

Of course having a central location for all of our application's state wouldn't be useful if we didn't use the data we're putting in.

Consuming state updates

Or, if we want to always be notified when the state changes, we can subscribe.

var ourData = store.getState();

var handler = function(){ console.log( store.getState() ); };

store.subscribe(handler);That's basically Redux in a nutshell.

Tying it together

In Redux, application state is stored in a nested object tree.

In React, data flows down the tree of components through props.

As you might expect, that means they work really well together.

Render subscription

Going back to our example, to add state to our application, we subscribe to the store and invoke render.

function render(){

ReactDOM.render(

<HelloPage state={ store.getState() } />,

document.getElementById("app")

)

}

store.subscribe(render);Then we have access to our store throughout our app, so long as we pass it down the chain via props.

It's a one-way street

Our data flows downhill only. If a component wants to update the state, it needs to dispatch an action, which will propagate throughout the application.

return (

<button onClick={

() => store.dispatch({ type: 'INCREMENT' })

}> Increment </button>

);When the event is dispatched, the store will pass the action to the reducer. When the new state is returned, the render method will be called.