Social Editions and Crowdsourcing

or

Ask not what the social edition can do for you

Tiago Sousa Garcia

tiago.sousa-garcia@newcastle.ac.uk

@tiagosousagarci

Collaboration

Crowdsourcing

Social Edition

Social Edition

textual interpretation and interrelation are almost wholly created and managed by a community of users participating in collective and collaborative knowledge building using social technologies

(Siemens et al. 2012)

- Web 2.0 paradigm

- All users are editors

- Responsibilities are shared equally

Crowdsourcing

crowdsourcing, in particular the form applied in the Humanities, is not an invention of the age of the Internet: the name may well be, but the concept is definitely not.

(Pierazzo 2015)

- 'Drudge work' done by volunteers

- Researchers review, correct and approve contributions

- Editors maintain complete control

Collaboration

The key word is collaboration

(Robinson 2010)

- Most print editions are collaborative

- Nearly all scholarly digital editions are collaborative

- All social editions are collaborative, but not all collaborative editions are social

Collaboration

Social Edition

Crowdsourcing

Why do a social edition / crowdsourcing?

Theoretical approach to editing

Community engagement

Transparency

Potentially time- and money-saving

And why not?

Quality of contributions by volunteers

Protecting the authority of the edition

Even the simpler tasks are arguably specialized

Potentially time- and money-wasting

Social Edition

Verse miscellany

Created with wikibooks

Freely edited by anyone

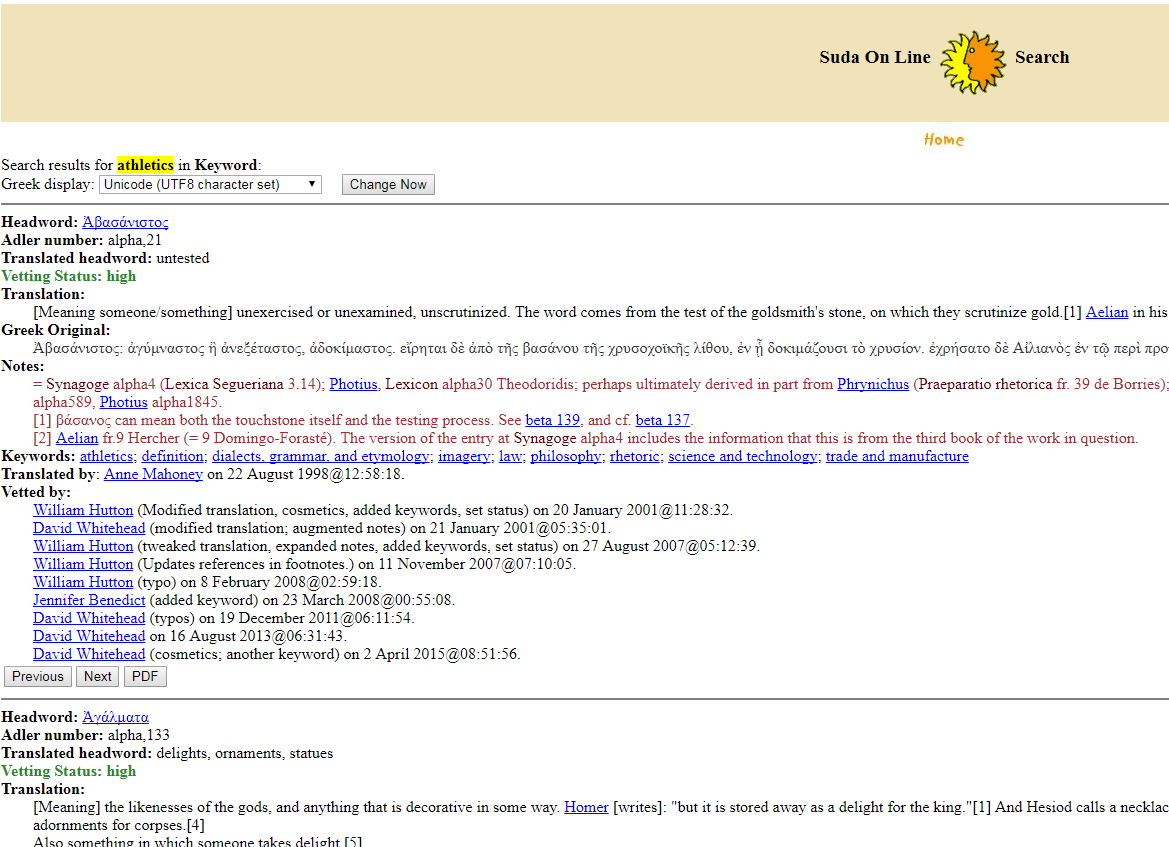

Social Edition

Translation of 10th century Byzantine Encyclopedia

Controlled community

Different levels of editorial access

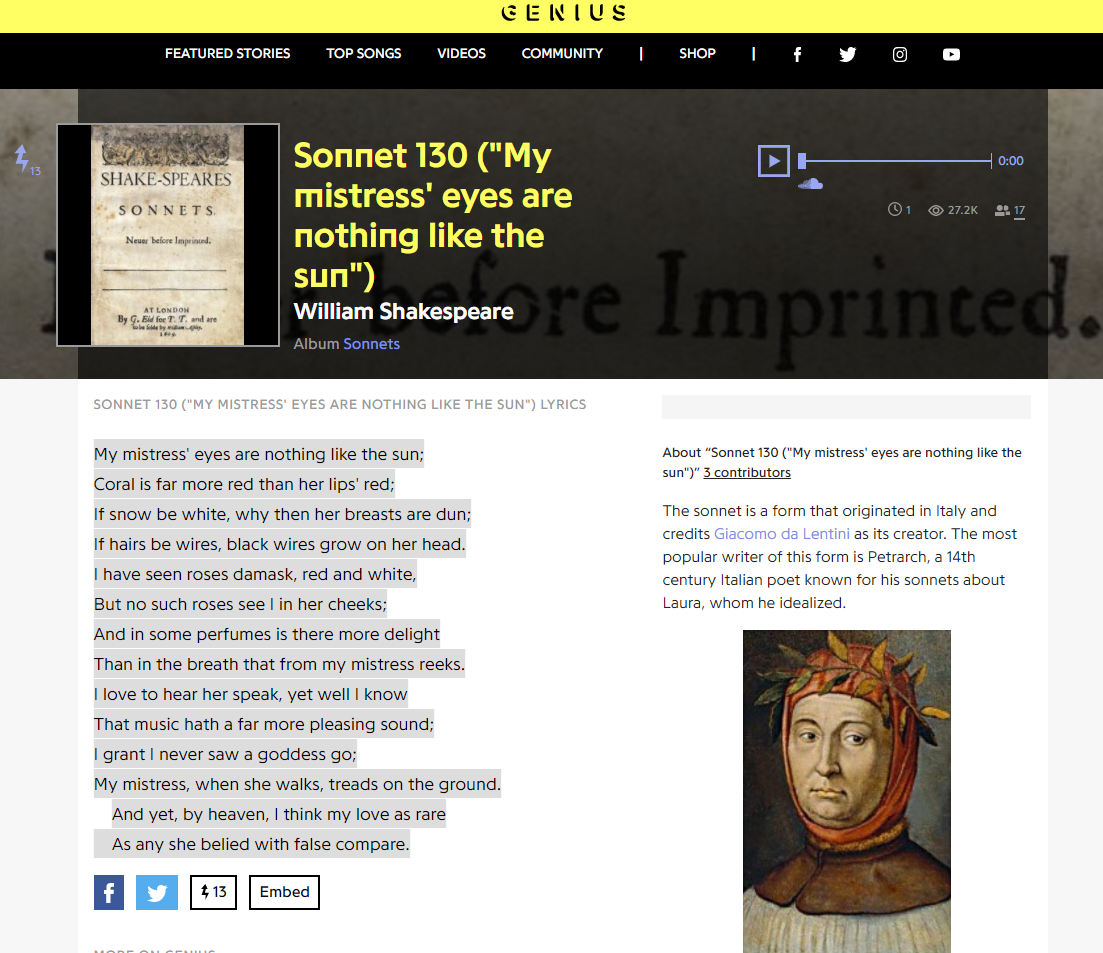

Social Edition (?)

Started as a platform for annotating rap lyrics

Expanded to an all-purpose annotation tool

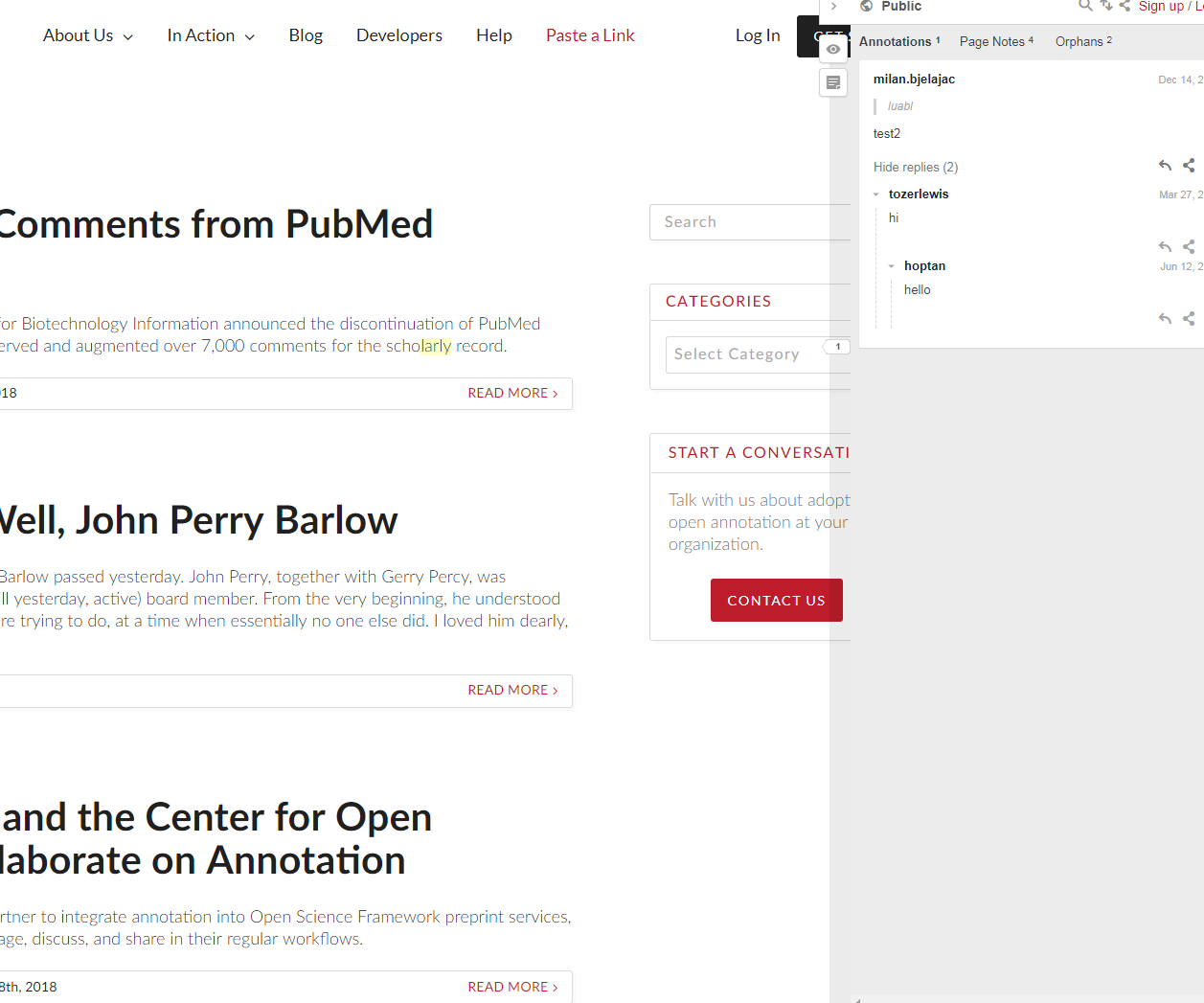

Social Edition (?)

Web annotation tool

Annotate anything on-line

Plenty of pedagogical uses

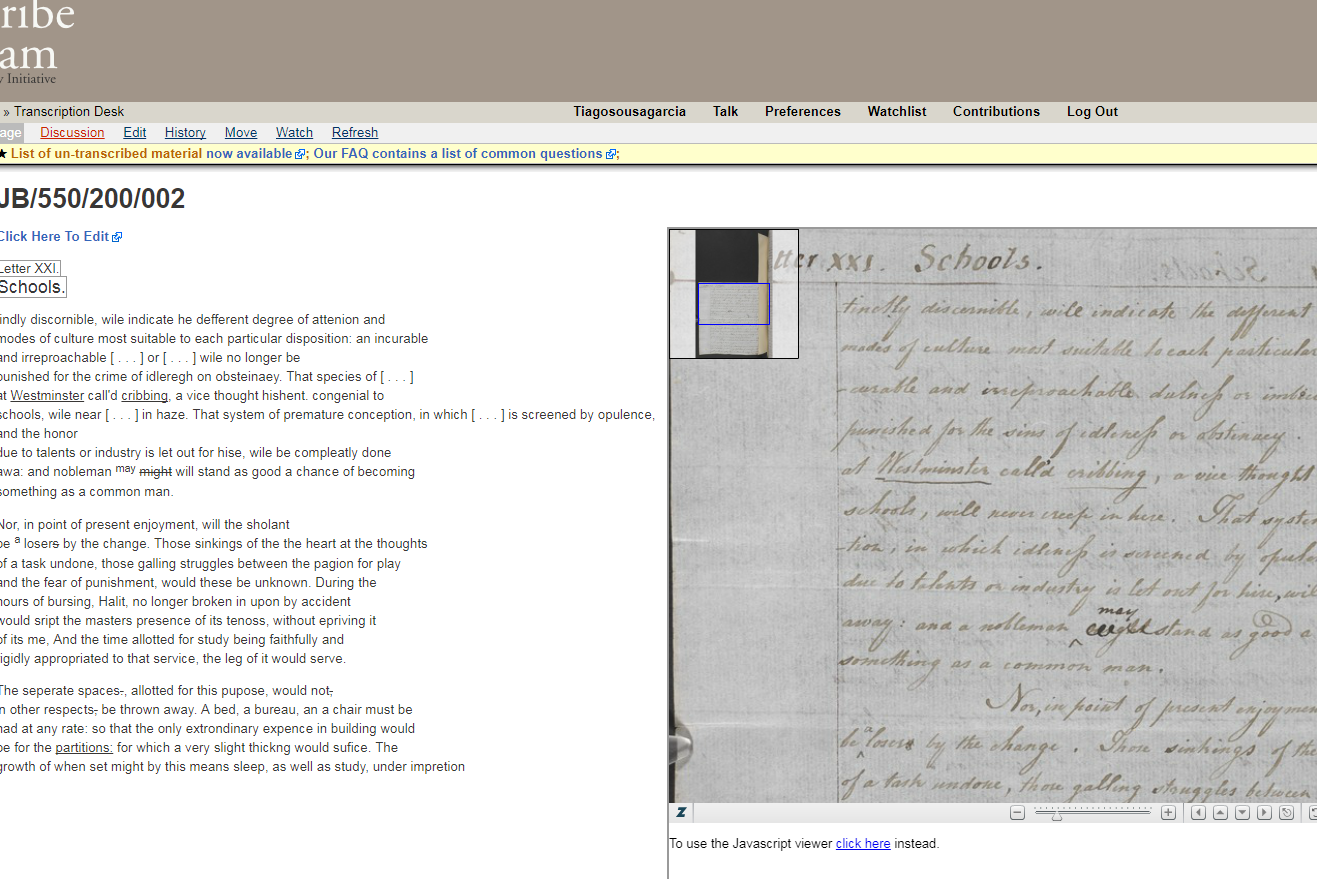

Crowdsourcing

Transcription of Jeremy Bentham's MSS

Transcriptions will be freely available online and form the basis of The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham

Volunteers transcribe and encode MSS, contributions are moderated

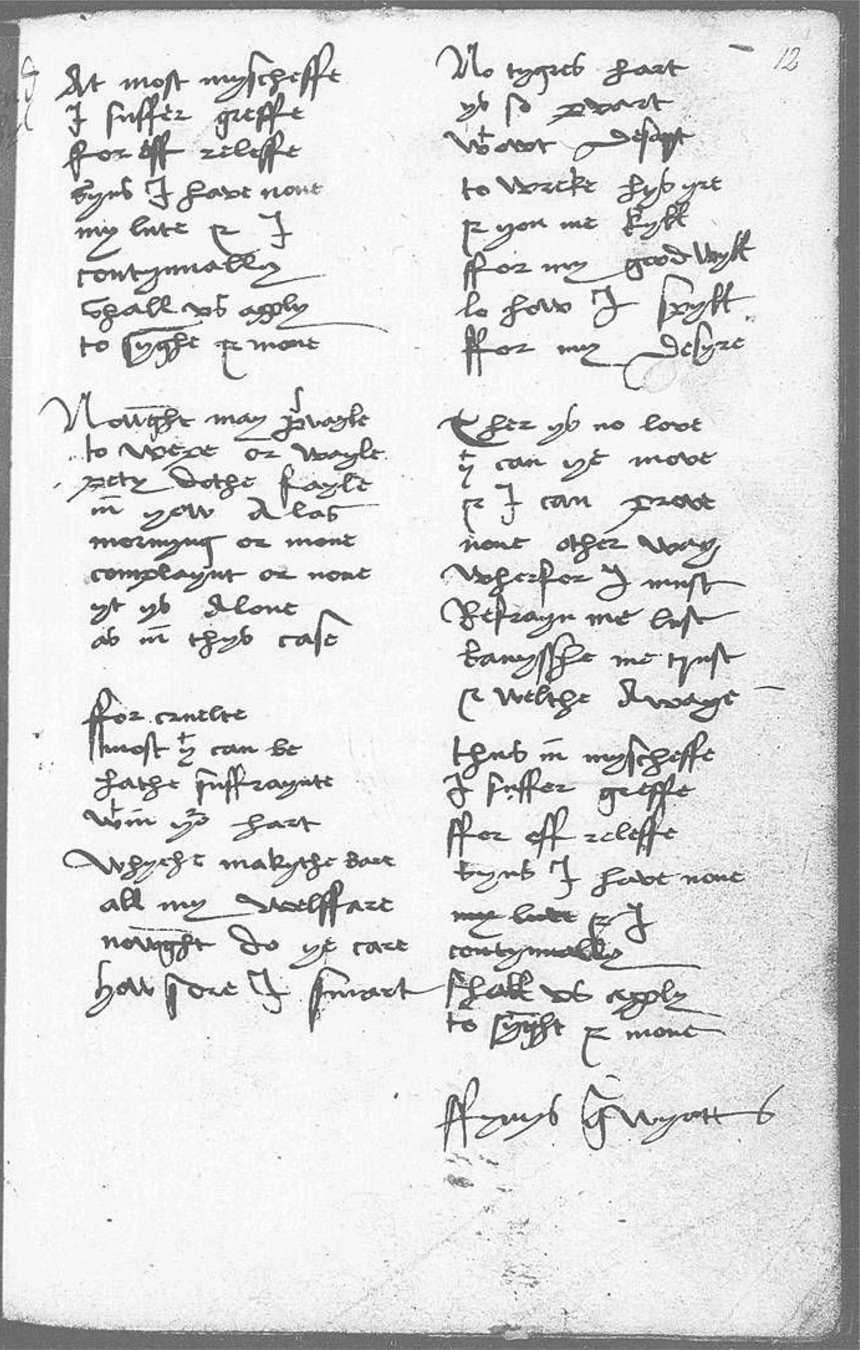

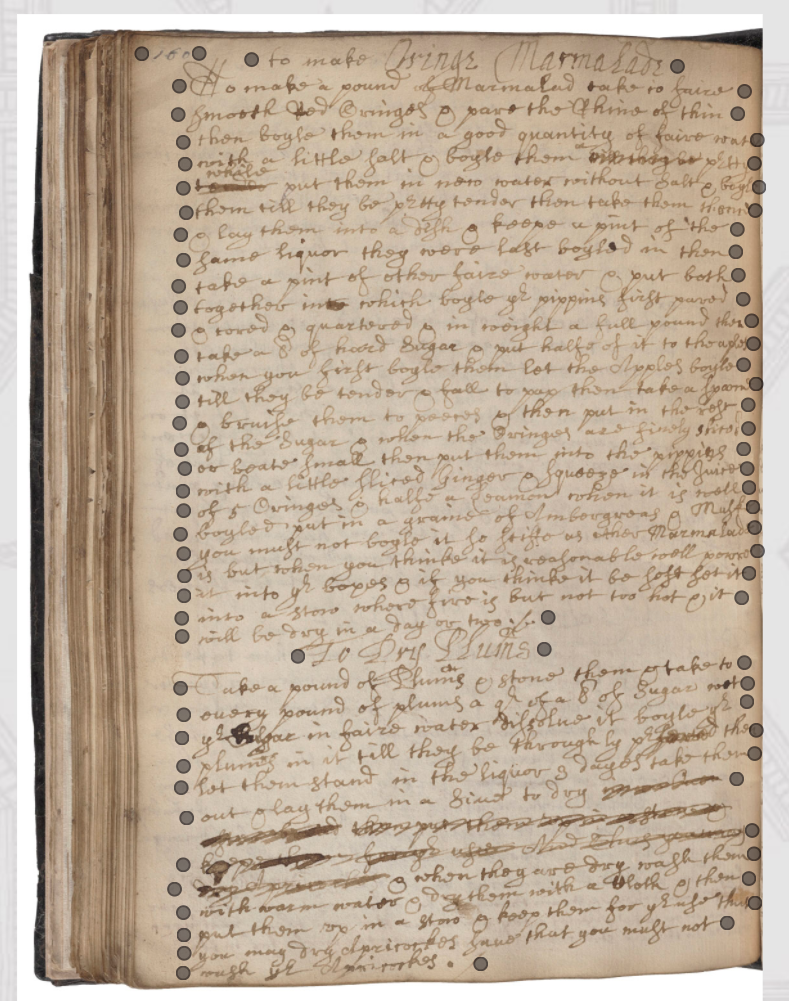

Crowdsourcing

Transcription of documents in or around Shakespeare's lifetime

Based on Zooniverse platform for crowdsourcing (or citizen science)

Volunteers transcribe lines of text, encoding is automatic

Discussion

Is a social edition an improvement over other approaches?

Are there any ethical implications with crowdsourcing?

How can we trust the scholarship of a social edition?

Do the costs of crowdsourcing outweigh the benefits?

Is SE/CS a good way of involving the community with research?

Could we use SE/CS as a pedagogical tool?

... and your questions?

Bibliography

Brown, Susan. “ Tensions and Tenets of Socialized Scholarship.” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 31, no. 2 (June 1, 2016): 283–300

Causer, Tim, et al. “ ‘Making Such Bargain’: Transcribe Bentham and the Quality and Cost-Effectiveness of Crowdsourced Transcription.” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities.

Deines, Nathaniel, et al. “ Six Lessons Learned from Our First Crowdsourcing Project in the Digital Humanities.” The Getty Iris, February 7, 2018.

Eggert, Paul. “ The Reader-Oriented Scholarly Edition. ” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 31, no. 4 (December 1, 2016): 797–810.

Meiman, Meg. “ Documentation for the Public: Social Editing in The Walt Whitman Archive .” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 31, no. 4 (December 1, 2016): 819–28.

Muri, Allison, et al. “ The Grub Street Project: A Digital Social Edition of London in the Long 18th Century .” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 31, no. 4 (December 1, 2016): 829–49.

Pierazzo, Elena. Digital Scholarly Editing: Theories, Models and Methods . Farnham: Ashgate, 2015.

Price, Kenneth M. “ The Walt Whitman Archive and the Prospects for Social Editing .” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 31, no. 4 (December 1, 2016): 866–74.

Robinson, Peter. “ Editing Without Walls.” Literature Compass 7, no. 2 (February 2010): 57–61.

Robinson, Peter. “ Chapter 7. Social Editions, Social Editing, Social Texts .” Digital Studies/Le Champ Numérique 6, no. 0 (April 25, 2016).

Saklofske, Jon, et al. “ Gaming the Edition: Modelling Scholarly Editions through Videogame Frameworks.” Digital Literary Studies 1, no. 1.

Shillingsburg, Peter. “ Reliable Social Scholarly Editing .” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 31, no. 4 (December 1, 2016): 890–97.

Siemens, Ray, et al. “ Toward Modeling the Social Edition: An Approach to Understanding the Electronic Scholarly Edition in the Context of New and Emerging Social Media.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 27, no. 4 (December 1, 2012): 445–61.