Cache

developer's day dream

Tester's NIGHTMARE

REALITY check

Cache Control is a mess if not done correctly.

Affects

-

Developers

-

Testers

-

Operations

-

Business Users

-

End Users

Cache request directives

no-cache

no-store

max-age = delta-seconds

max-stale [=delta-seconds]

min-fresh = delta-seconds

no-transform

only-if-cached

CACHE REsponse DIRECTIVES

public

private [="field-name"]

no-cache [="field-name"]

no-store

no-transform

must-revalidate

proxy-revalidate

max-age = delta-seconds

s-maxage = delta-seconds

What is Cacheable

By default, a response is cacheable if the requirements of the request method, request header fields, and the response status indicate that it is cacheable.

An origin server can override the default cacheability of a response.

Cache-control: public

W3C (From RFC2616 section 14.9.1)

Indicates that the response MAY be cached by any cache, even if it would normally be non-cacheable or cacheable only within a non- shared cache.

LMT

Most generic caching, if authorization permits, it MAY be cached by anyone.

CACHE-CONTROL: PRIVATE

W3C (From RFC2616 section 14.9.1)

Indicates that all or part of the response message is intended for a single user and MUST NOT be cached by a shared cache. This allows an origin server to state that the specified parts of the response are intended for only one user and are not a valid response for requests by other users.

LMT

shared caches (such as proxy caches) should not cache the response. A private (non-shared) cache MAY cache the response. Also, do not confuse private with privacy.

Cache-control: no-cache

W3C (From RFC2616 section 14.9.1)

If the no-cache directive does not specify a field-name, then a cache MUST NOT use the response to satisfy a subsequent request without successful revalidation with the origin server. This allows an origin server to prevent caching even by caches that have been configured to return stale responses to client requests.

If the no-cache directive does specify one or more field-names, then a cache MAY use the response to satisfy a subsequent request, subject to any other restrictions on caching. However, the specified field-name(s) MUST NOT be sent in the response to a subsequent request without successful revalidation with the origin server. This allows an origin server to prevent the re-use of certain header fields in a response, while still allowing caching of the rest of the response.

Note: Most HTTP/1.0 caches will not recognize or obey this directive.

LMT

Ideally no useragent should cache this request. But not everyone follows W3C.

[do you ?]

Though this directive sounds like it is instructing the browser not to cache the page, there’s a subtle difference. The “no-cache” directive, according to the RFC, tells the browser that it should revalidate with the server before serving the page from the cache. Revalidation is a neat technique that lets the application conserve band-width. If the page the browser has cached has not changed, the server just signals that to the browser and the page is displayed from the cache.

Hence, the browser (in theory, at least), stores the page in its cache, but displays it only after revalidating with the server. In practice, IE and Firefox have started treating the no-cache directive as if it instructs the browser not to even cache the page. We started observing this behavior about a year ago. We suspect that this change was prompted by the widespread (and incorrect) use of this directive to prevent caching.

Cache-Control: no-store

W3C (From RFC2616 section 14.9.1)

The purpose of the no-store directive is to prevent the inadvertent release or retention of sensitive information (for example, on backup tapes). The no-store directive applies to the entire message, and MAY be sent either in a response or in a request. If sent in a request, a cache MUST NOT store any part of either this request or any response to it. If sent in a response, a cache MUST NOT store any part of either this response or the request that elicited it. This directive applies to both non-shared and shared caches. "MUST NOT store" in this context means that the cache MUST NOT intentionally store the information in non-volatile storage, and MUST make a best-effort attempt to remove the information from volatile storage as promptly as possible after forwarding it.

Even when this directive is associated with a response, users might explicitly store such a response outside of the caching system (e.g., with a "Save As" dialog). History buffers MAY store such responses as part of their normal operation. The purpose of this directive is to meet the stated requirements of certain users and service authors who are concerned about accidental releases of information via unanticipated accesses to cache data structures. While the use of this directive might improve privacy in some cases, we caution that it is NOT in any way a reliable or sufficient mechanism for ensuring privacy. In particular, malicious or compromised caches might not recognize or obey this directive, and communications networks might be vulnerable to eavesdropping.

LMT

This is the most secure of the cache-control directives. It tells the browser not only not to cache the page, but also not to even store the page in its cache folder. Whenever you’re serving a sensitive page, this is the cache control directive to use.

Notice that of late, “cache-control: no-cache” has also started behaving like the “no-store” directive. To be on the safer side, we recommend that you use both “no-cache” and “no-store” when serving sensitive pages.

GHOSTS from the past

Pragma: No-cache

This is a HTTP 1.0 directive that was retained in HTTP 1.1 for backward compatibility. When specified in HTTP requests, this directive instructs proxies in the path not to cache the request. This is useful when you are submitting sensitive details like usernames and passwords in the request.

Notice that “pragma: no-cache” is linked to requests, and not responses. The RFC did not specify the behavior of this directive for responses. Hence, this directive does NOT instruct the browser not to cache a page. We often see this tag being misused when a page is served to the browser. Developers mistakenly set this directive expecting that the page will not be cached on the browser.

For all practical purposes, you can ignore this directive today. HTTP 1.1 introduced better directives, as we’ll see shortly.

GHosts from the past

Expires Header

This is yet another HTTP 1.0 directive that was retained for backward compatibility. This directive tells the browser when a page is set to expire. Once the page expires, the browser does not display the page to the user. Instead it shows a message like “Warning: Page has expired”.

In earlier days, developers played a nifty trick with this directive to ensure that a page expires immediately and is not served from the cache: they would set the expiration date to a day in the distant past. Thus, the browser treats the page has expired and never displays it from cache.

Though the page is not served from cache, browsers still used to store the page in the cache. You could navigate to the cache folder of the browser and open the file directly from there. Thus, this was not really a secure directive.

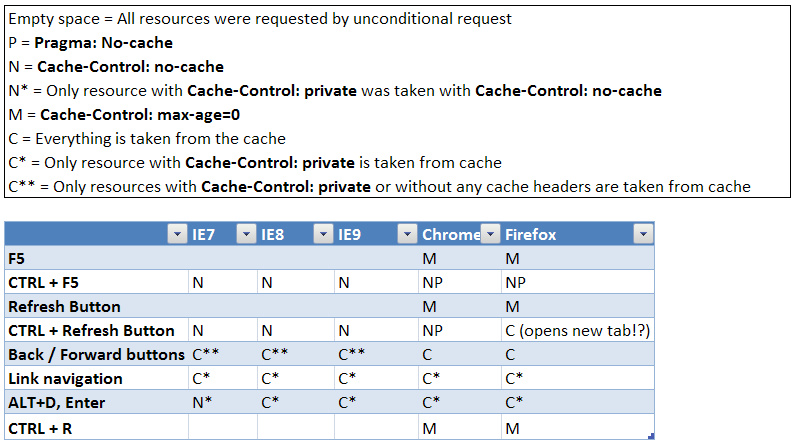

Dubious F5*

http://podlipensky.com/examples/refreshbutton/index.html

* F5 doesn't refer to F5 Networks. It refers to the keyboard button.