code at work

Wagner Lab, Stanford

2014 October 2

Kurt MacDonald

Design Director, Maginatics

Software

Development

Cycle

- Requirements

- Whiteboard Design Sessions

- Programming

- Source Code Management

- Writing Commit Messages

- Code Review Process

- Style Guides

- Documenting Code

- Automated Tools

- Unit Tests

- Integration Tests

- QA

- Code Demonstration

- Code Reading

- “Tech Talk” Presentations

- Post-mortem

Culture

We do this stuff because of who we are.

Process

We follow these steps because they are the agreed upon workflow for our organization.

hard

git

is

good

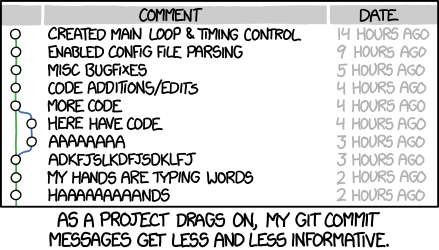

On commit messages

Btw, the commit message rules we use in the kernel really *are* objectively better. The fact that some other projects don't care that much is fine. But just compare kernel message logs to other projects, and I think you'll find that no, it's not just "my opinion". We do have standards, and the standards are there to make for better logs.

“Merge branch 'asdfasjkfdlas/alkdjf' into sdkjfls-final”

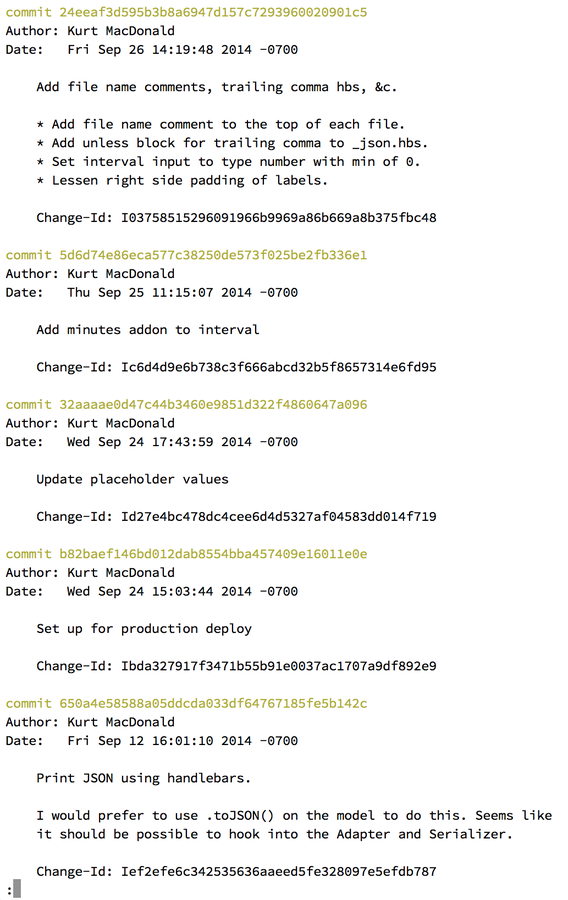

Capitalized, short (50 chars or less) summary

More detailed explanatory text, if necessary. Wrap it to about 72

characters or so. In some contexts, the first line is treated as the

subject of an email and the rest of the text as the body. The blank

line separating the summary from the body is critical (unless you omit

the body entirely); tools like rebase can get confused if you run the

two together.

Write your commit message in the present tense: "Fix bug" and not "Fixed

bug." This convention matches up with commit messages generated by

commands like git merge and git revert.

- Bullet points are okay, too

- Typically a hyphen or asterisk is used for the bullet, preceded by a

single space, with blank lines in between, but conventions vary here

- Use a hanging indent

Commit Message Format

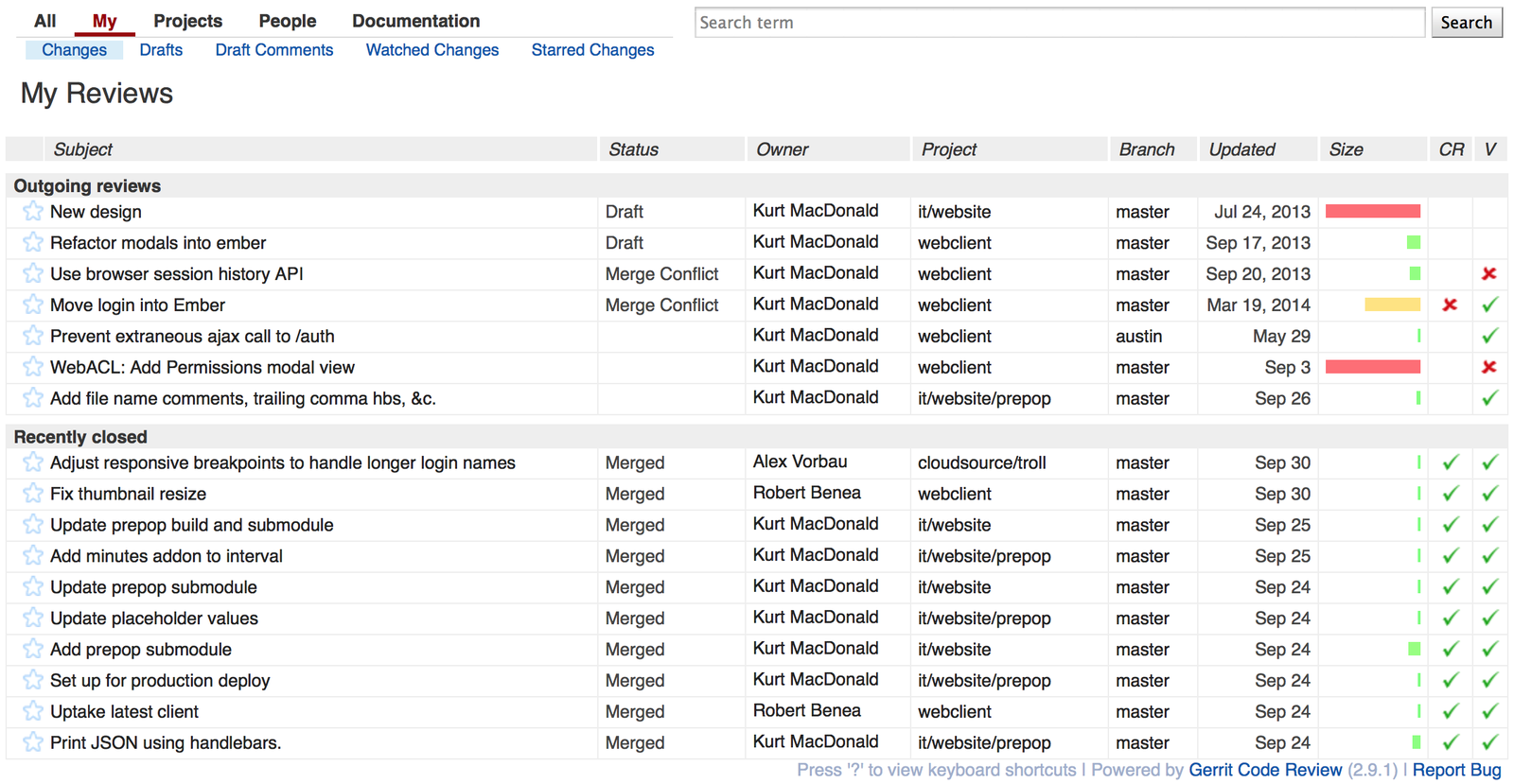

code review

At Maginatics

All code that goes into the product must go through code review.

There are still bugs.

There are still style clashes.

There is still miscommunication.

→ Test coverage.

→ Maintain a style guide.

→ Make things simple and clear.

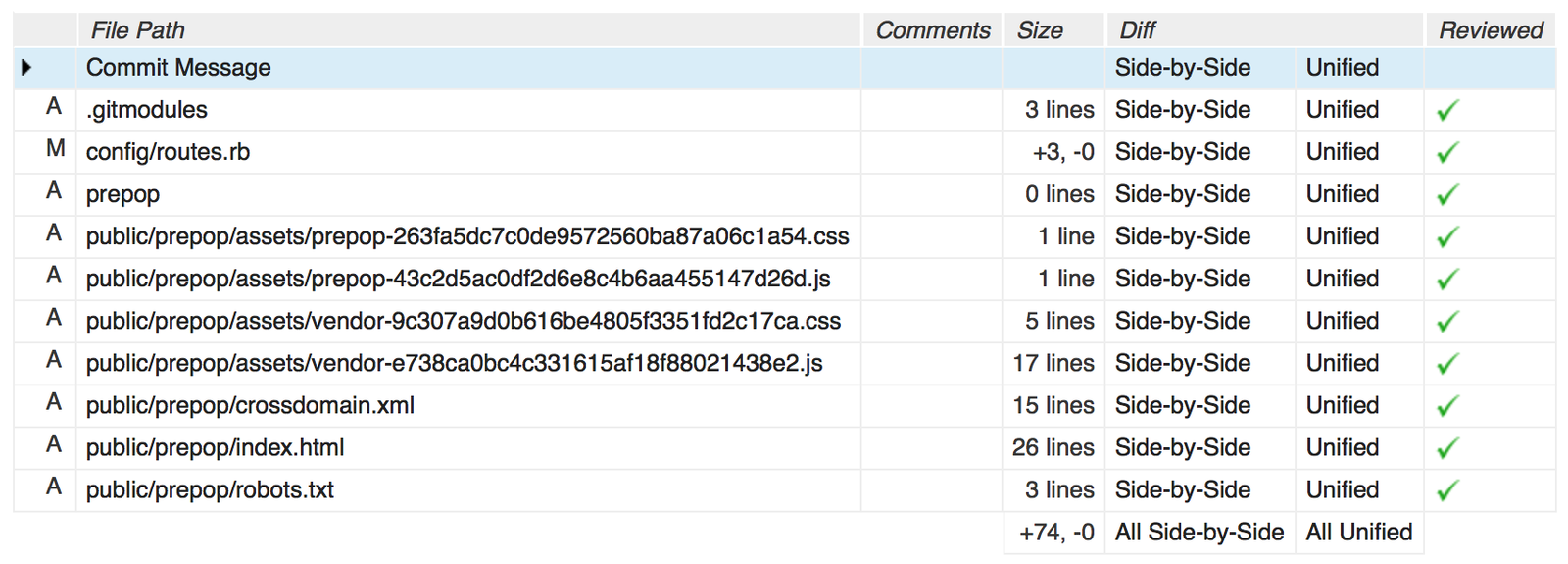

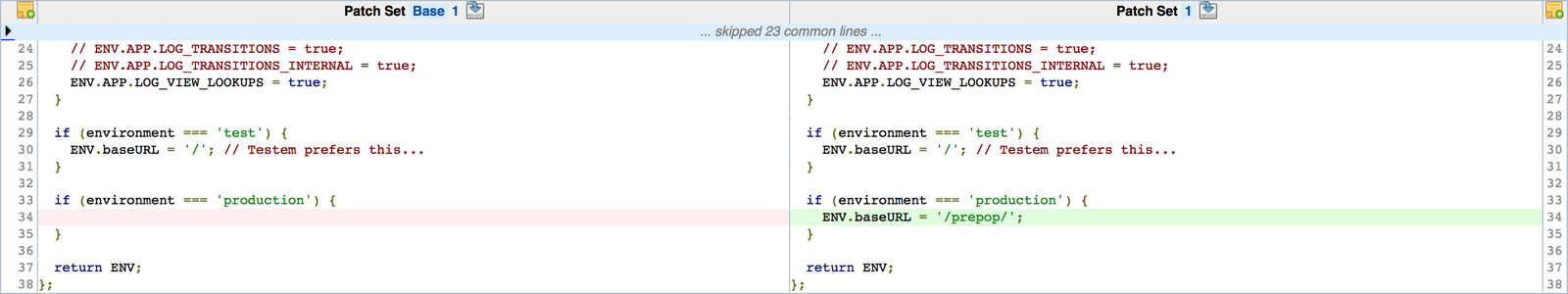

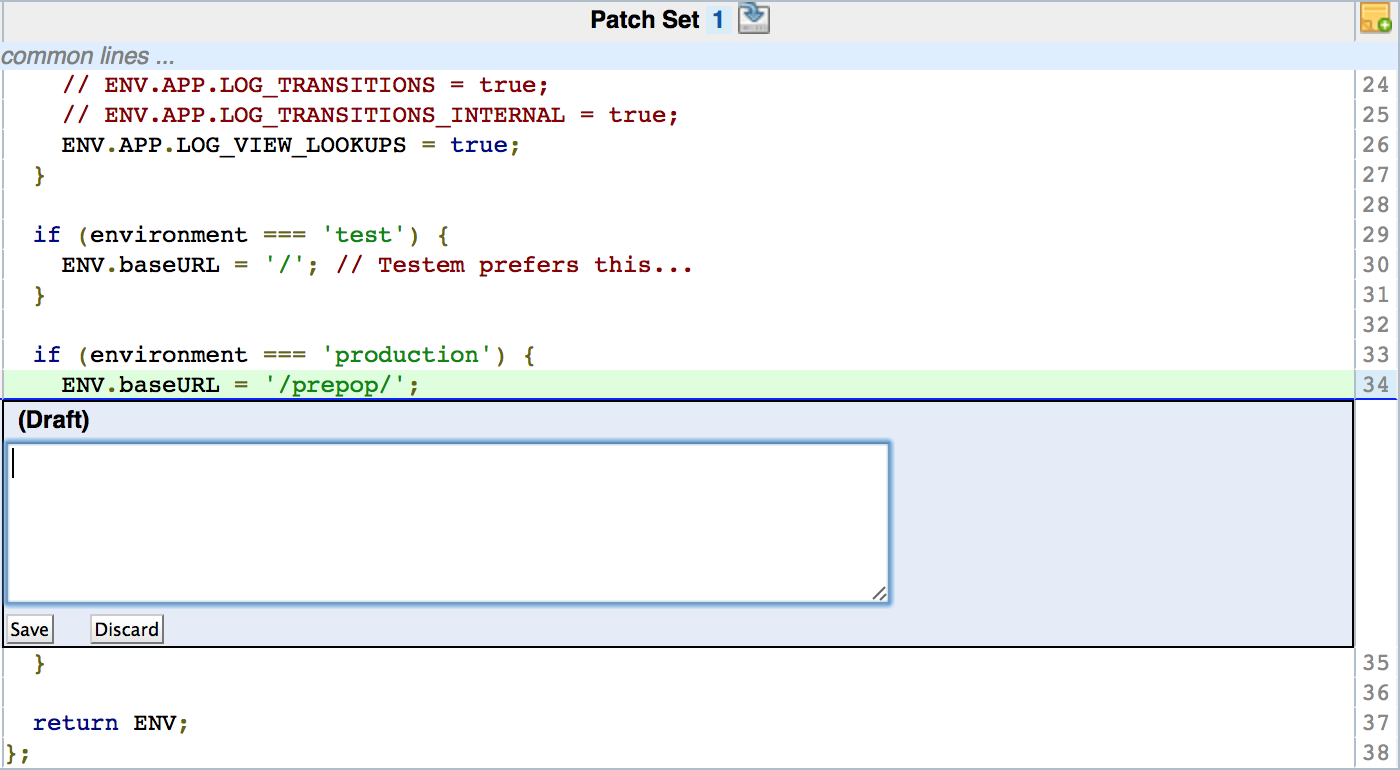

Gerrit

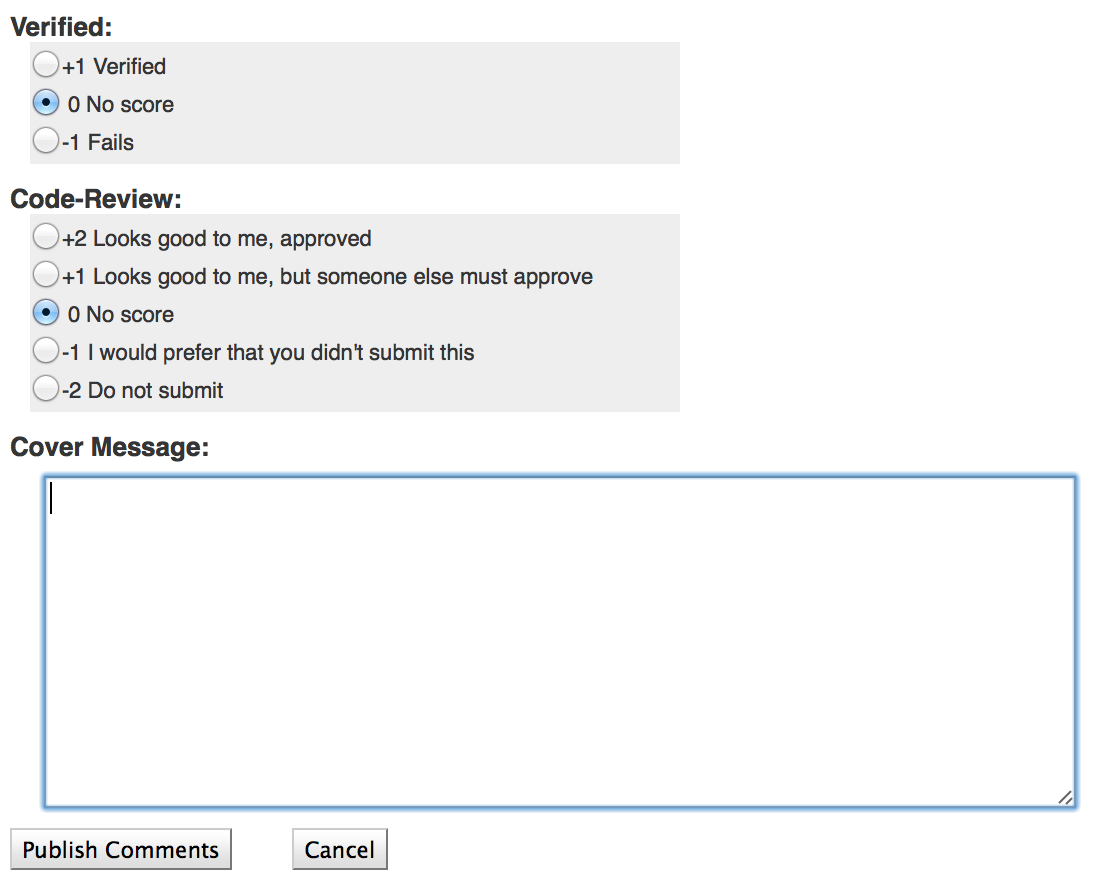

Submit Review

Verify

A patch must pass the verifier before it can be merged. Jenkins, our CI server, automatically runs the test scripts for each project when a new patch set is pushed.

Score

Looks good to me, approved

Looks good to me, but someone else must approve

No score

I would prefer that you did not submit this

Do not submit

+2

+1

0

-1

-2

Style

Does it adhere to the house style?

Correctness

Does it work?

Review Guidelines and Tips

Following the below guidelines to improve review quality and speed up the process:

Try to keep review requests small.

This makes the history clear and it can dramatically speed up response times from reviewers.

Try to split independent changes into different requests.

Changes that are logically separate should be split into separate commits.

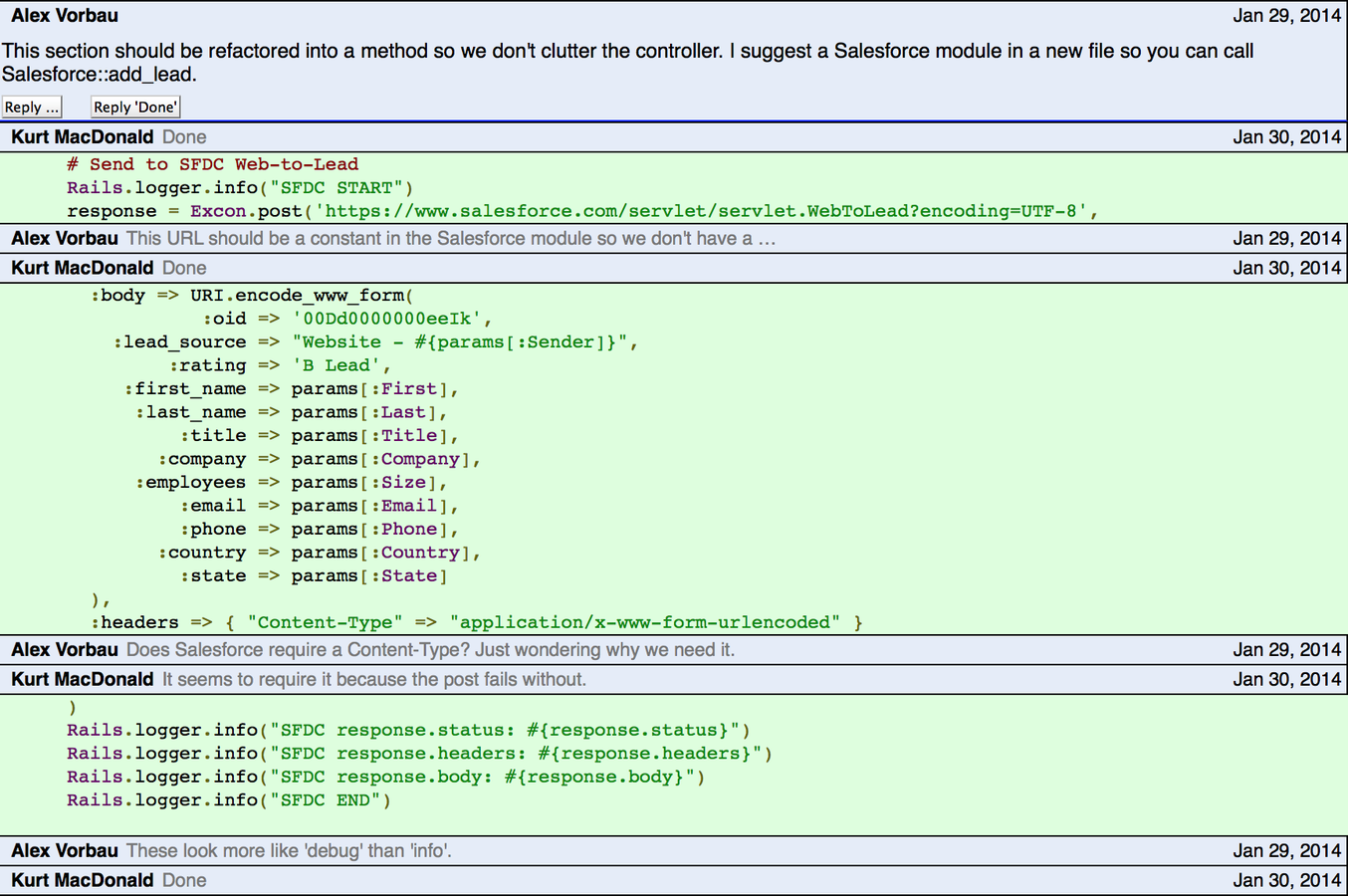

Give feedback on reviewers’ comments

This could be as simple as a “Done” comment. This saves time for the reviewers in followup.

Constructive feedback is always welcome.

The goal is to improve the quality of our code.

1.

2.

3.

4.

Quotes from Coworkers

“If there is too much overhead/frustration, then you will not do it.”

“No shame in bad code, shame in not fixing it (or publishing bad code).”

“All about people: easy to be passive aggressive. Sometimes better to talk directly.”

“Pick a ‘decider of all things that don’t matter’ to prevent bike-shedding.”

“Writing good commit messages helps people know if they even need to look at the code.”

How many people review a given piece of code?

To what extent is the code actually reviewed? i.e., do you simply read it, or do you actually test it by pushing data through?

At what point in the code writing process is the code reviewed? i.e., every time a minor change is made vs. major change vs. when an entirely new script is written?

How do you make the process fair so that people dedicate approximately equal amounts of time to code review?

We assume you use GitHub or something similar for accessing code?

don’t

use

gerrit

do

use

github

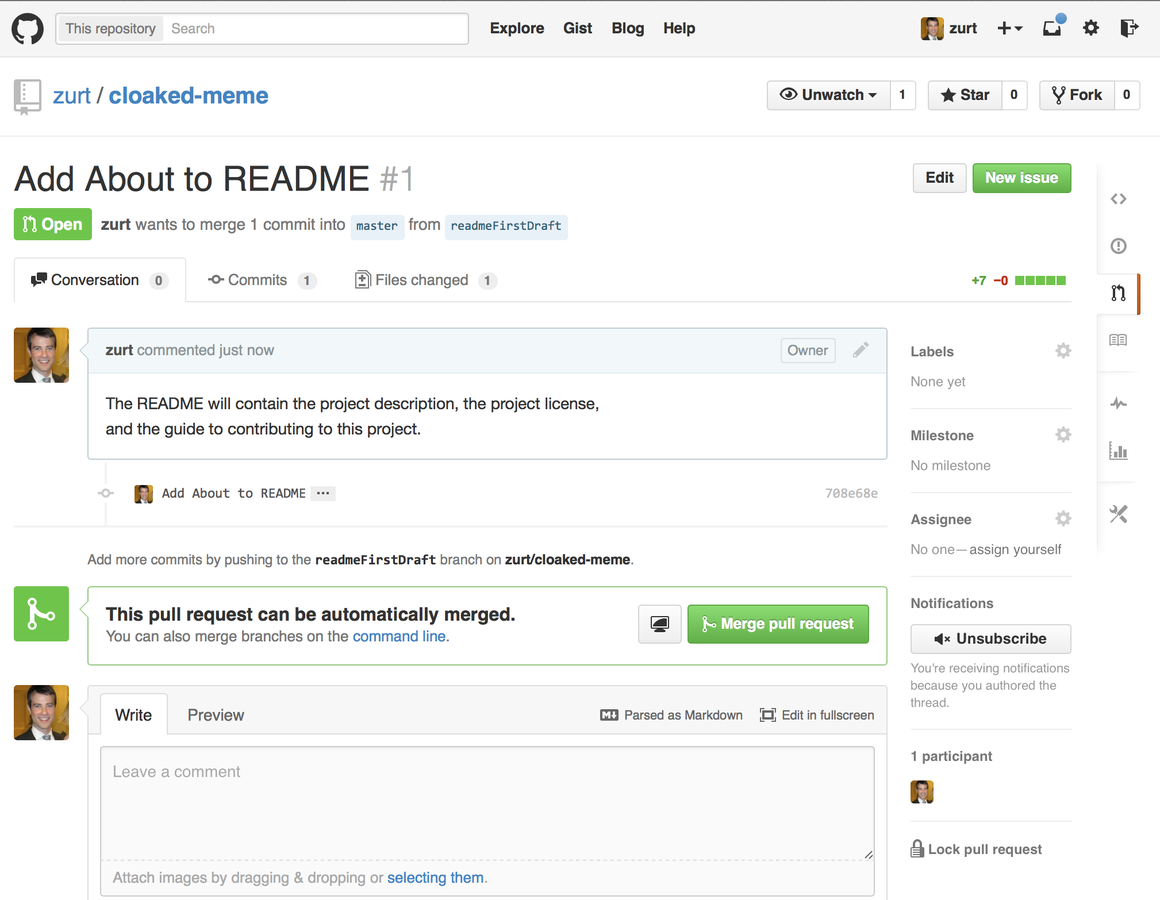

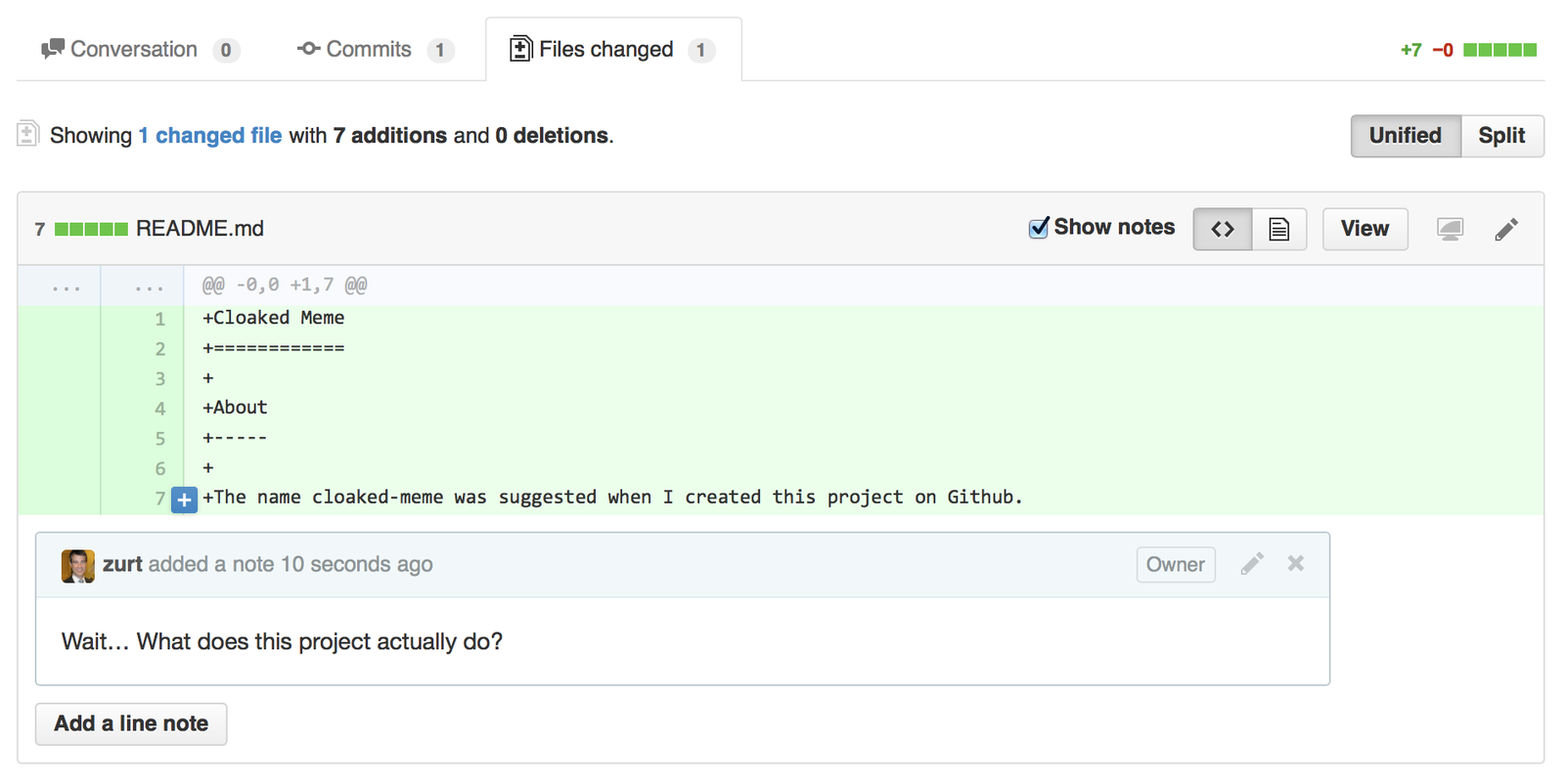

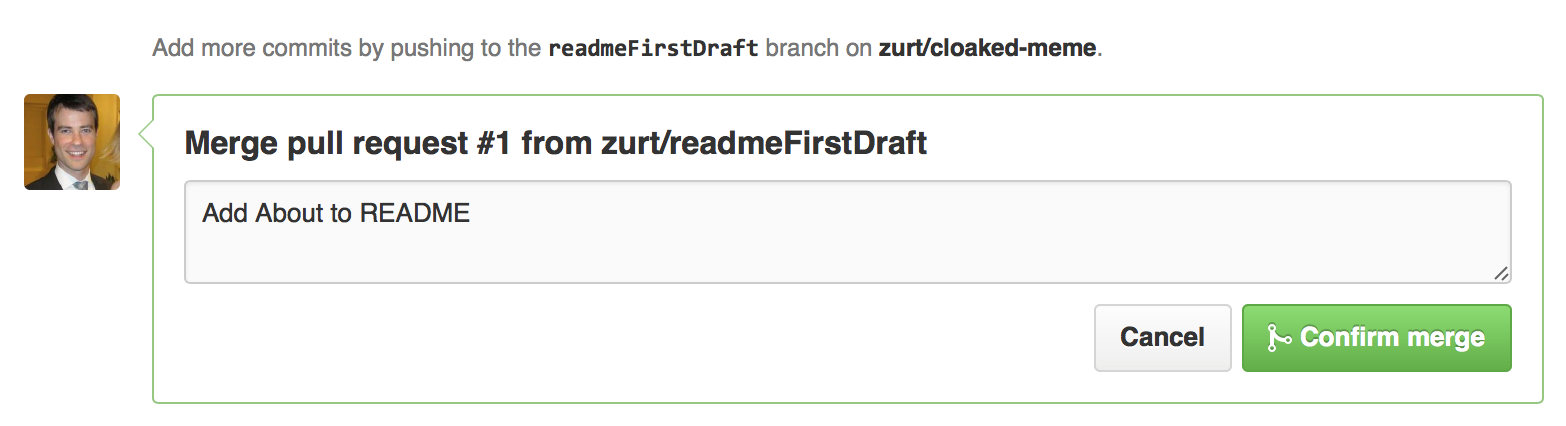

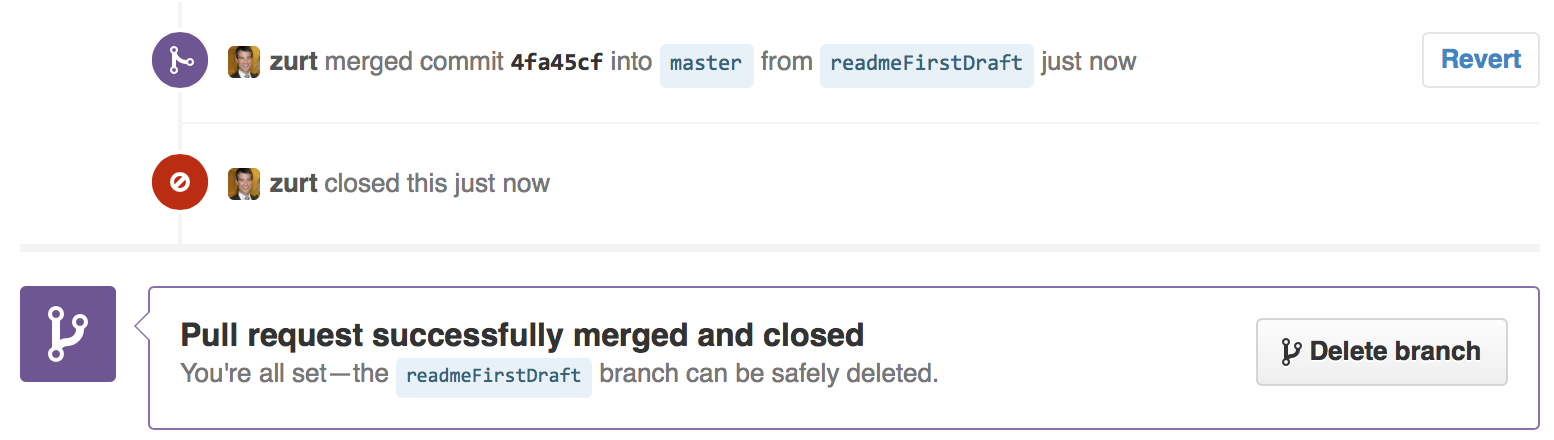

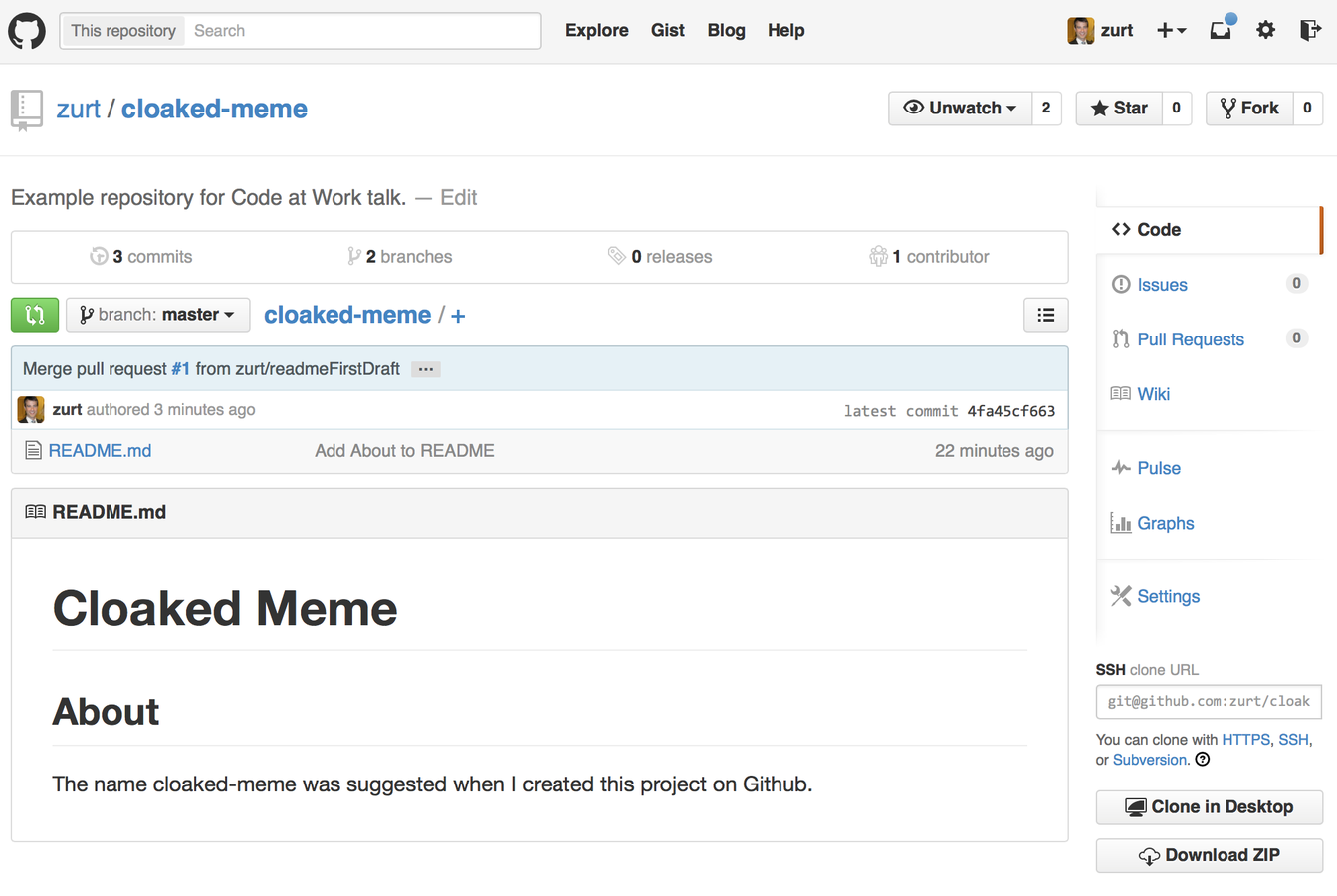

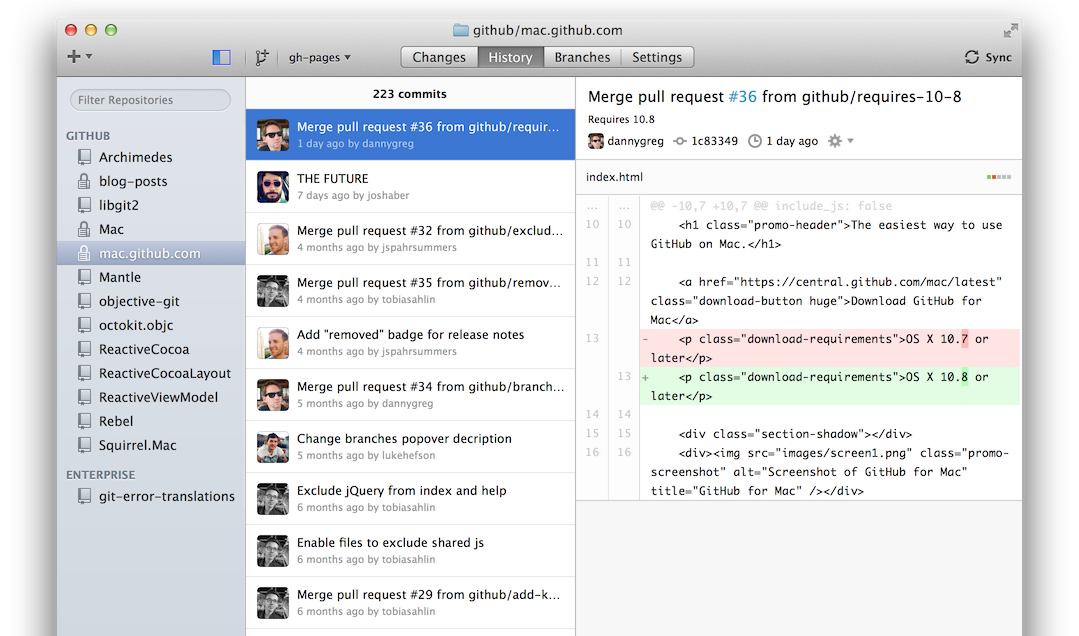

Pull Requests

Less formal code review.

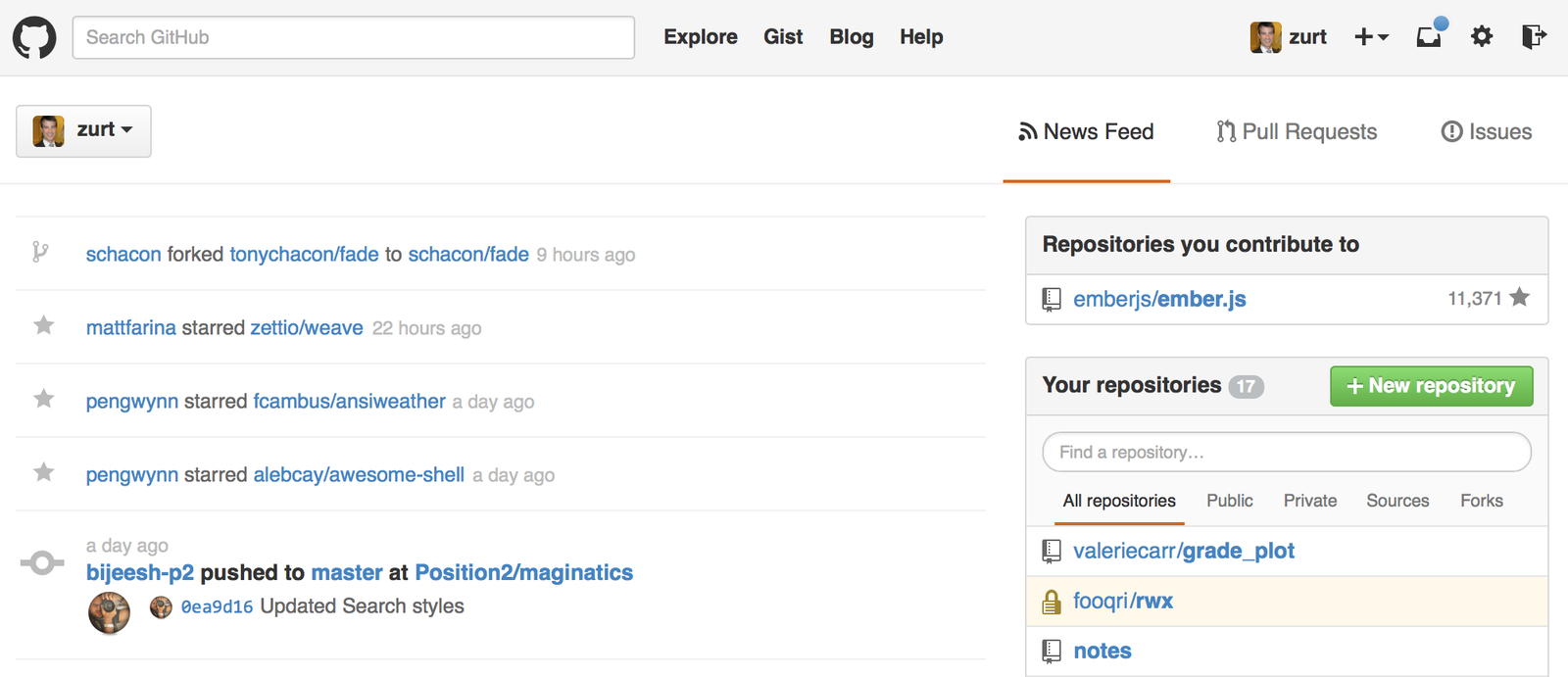

GitHub Dashboard

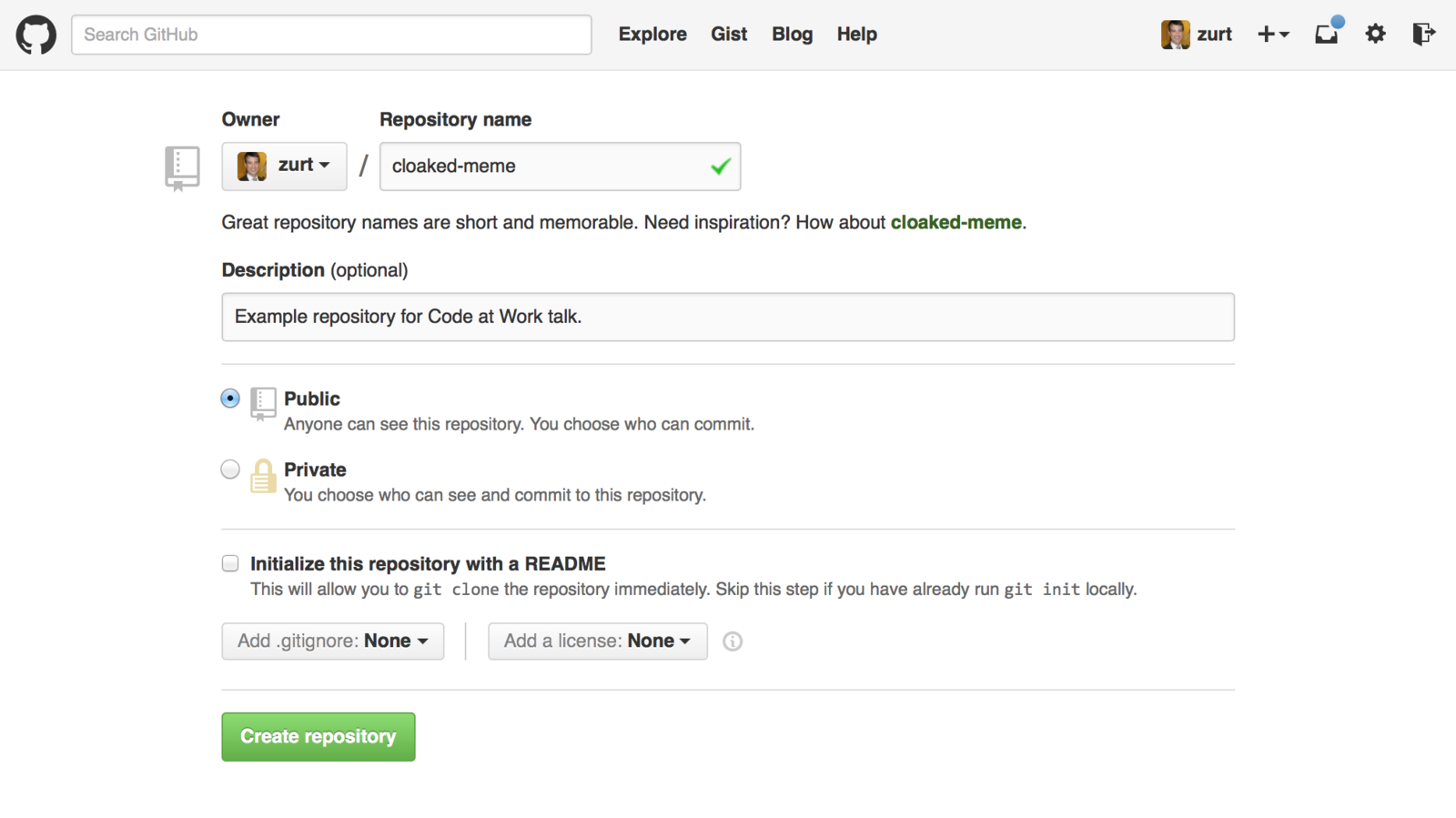

New Repository

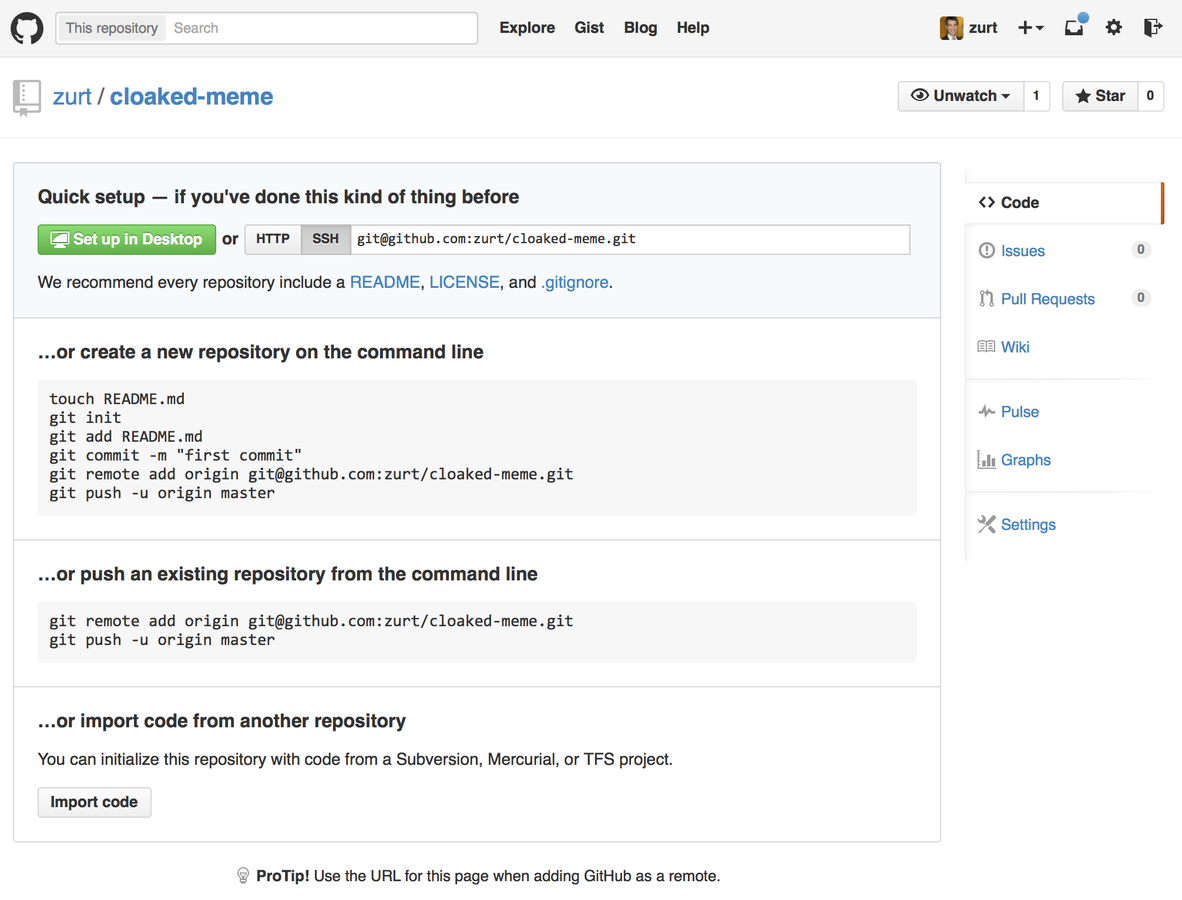

Next Steps

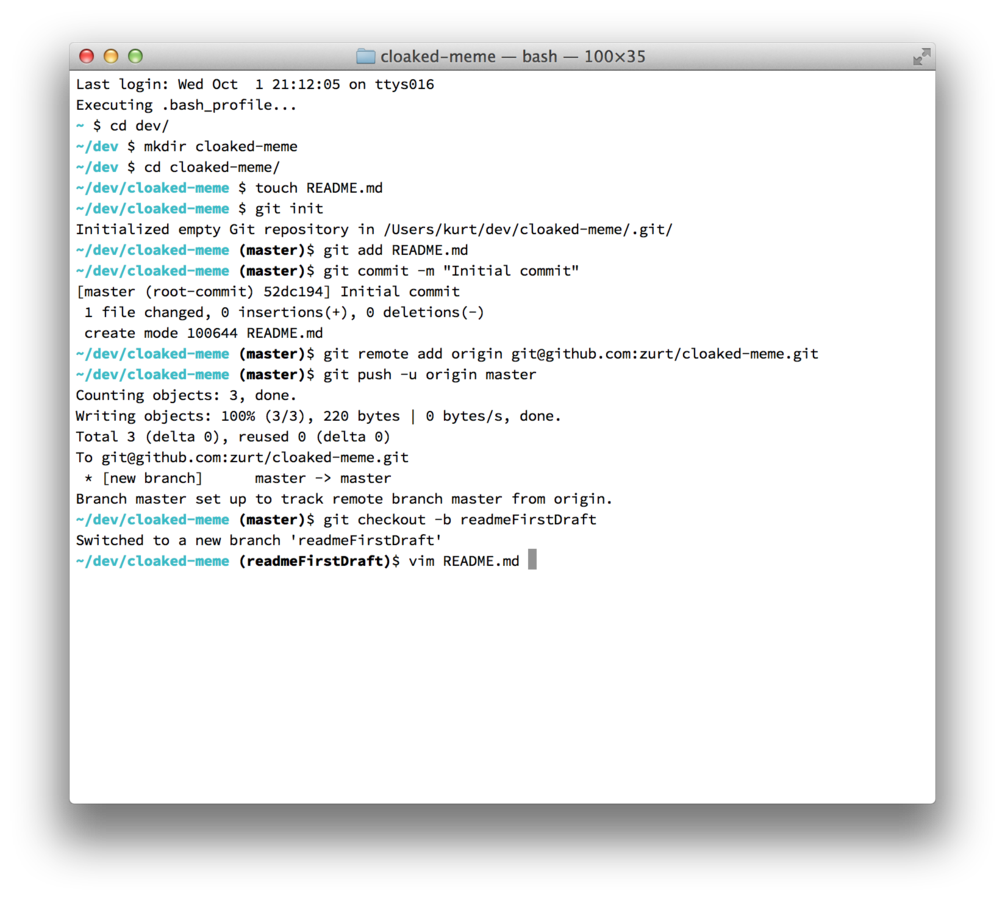

Create Local Repository

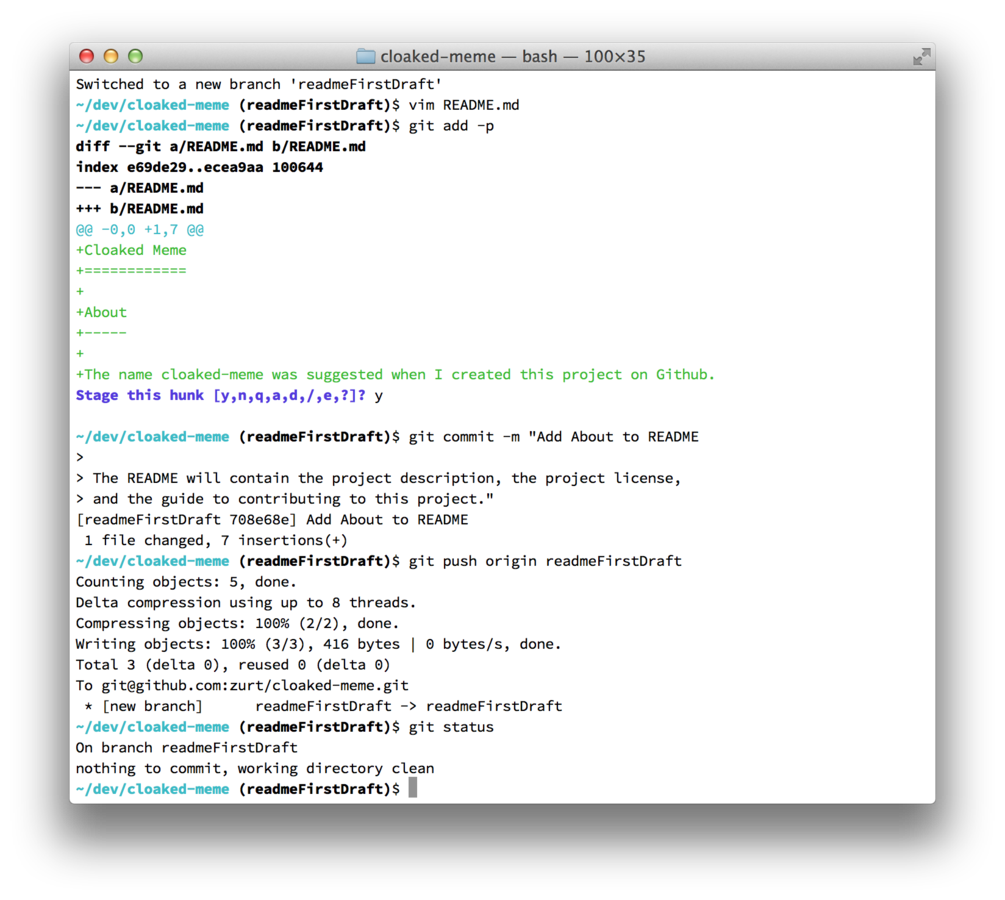

Add Code On A New Branch

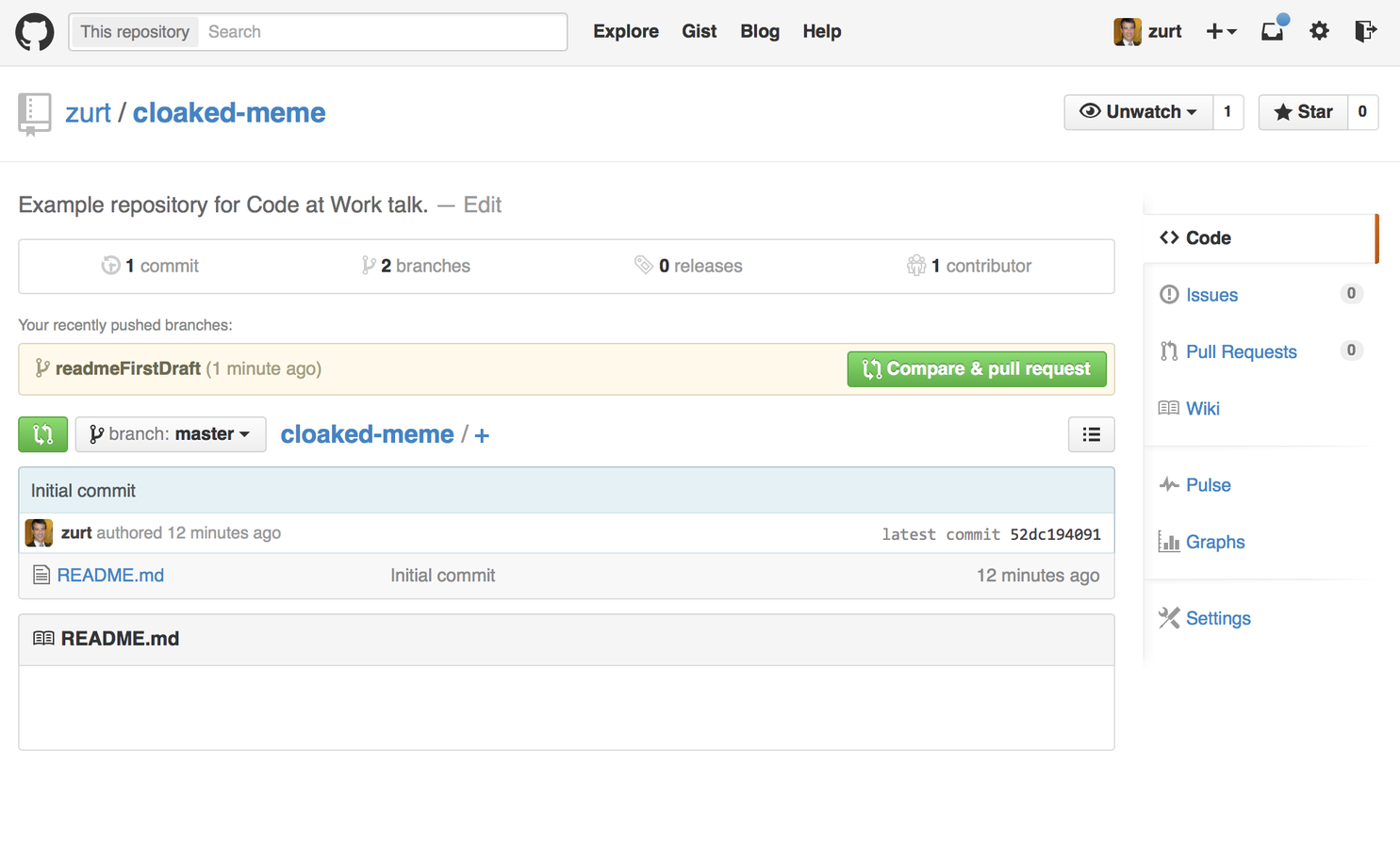

Pushed Branch Appears

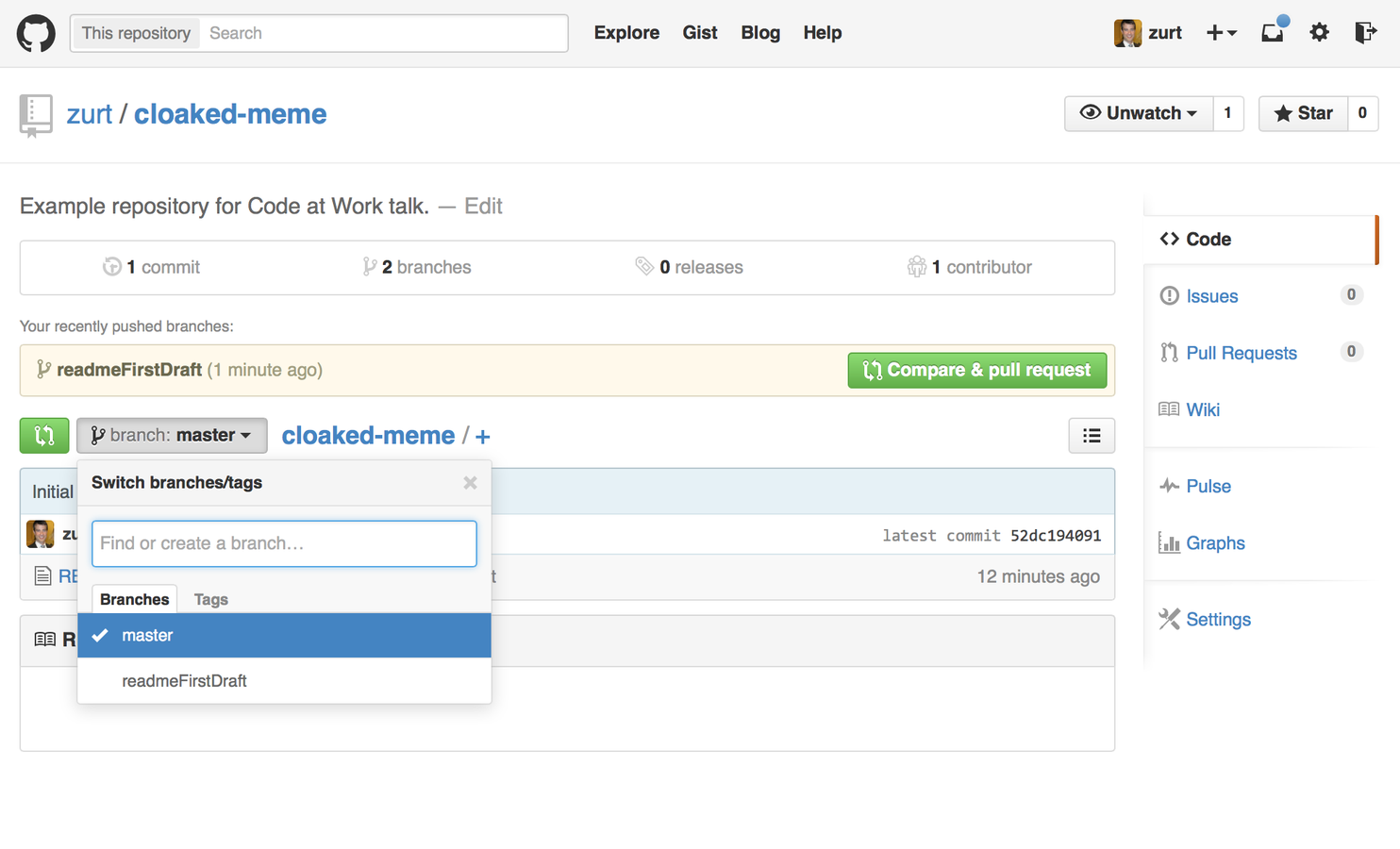

Switch Between Branches

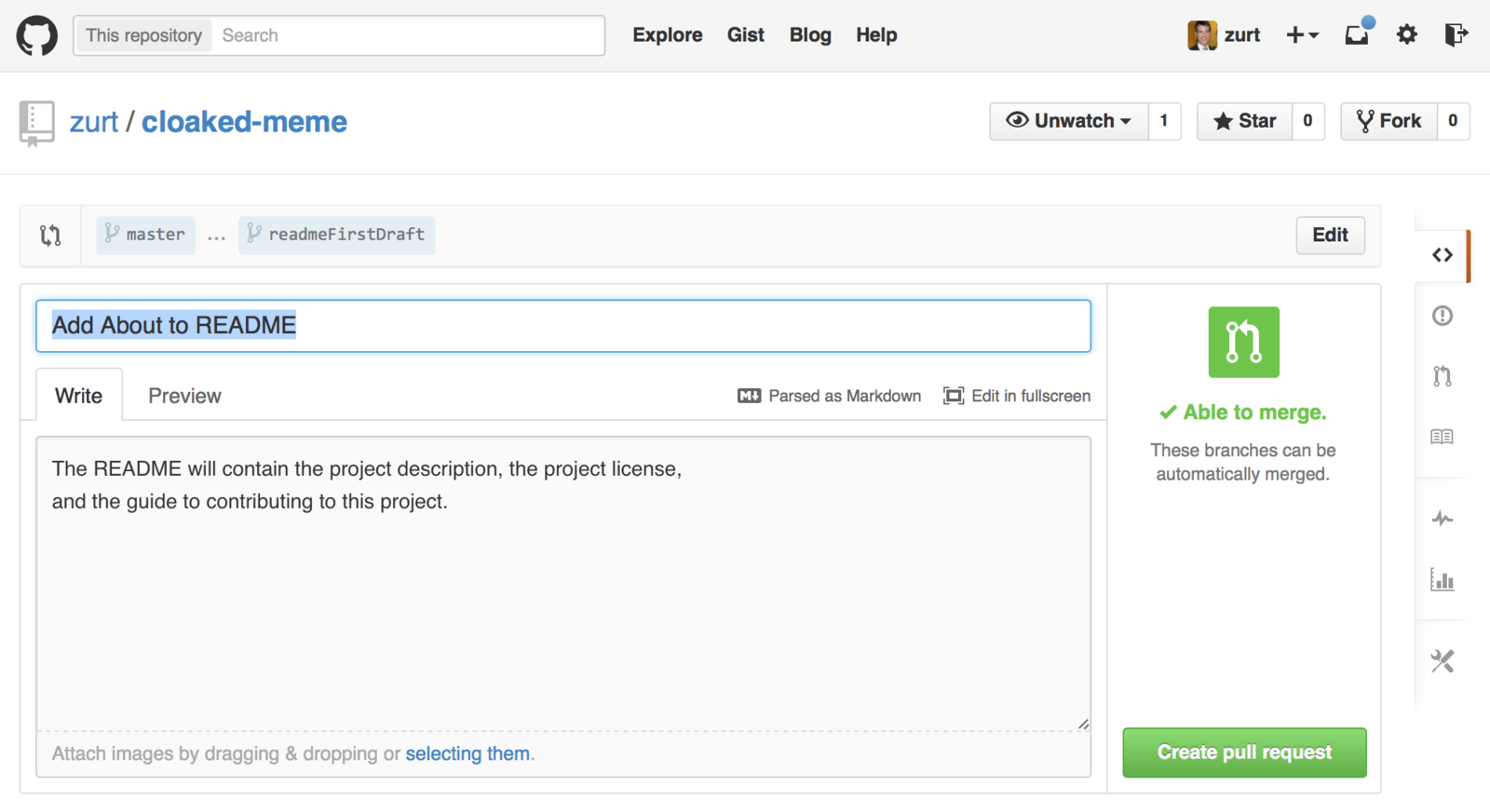

Create Pull Request

Open Pull Request

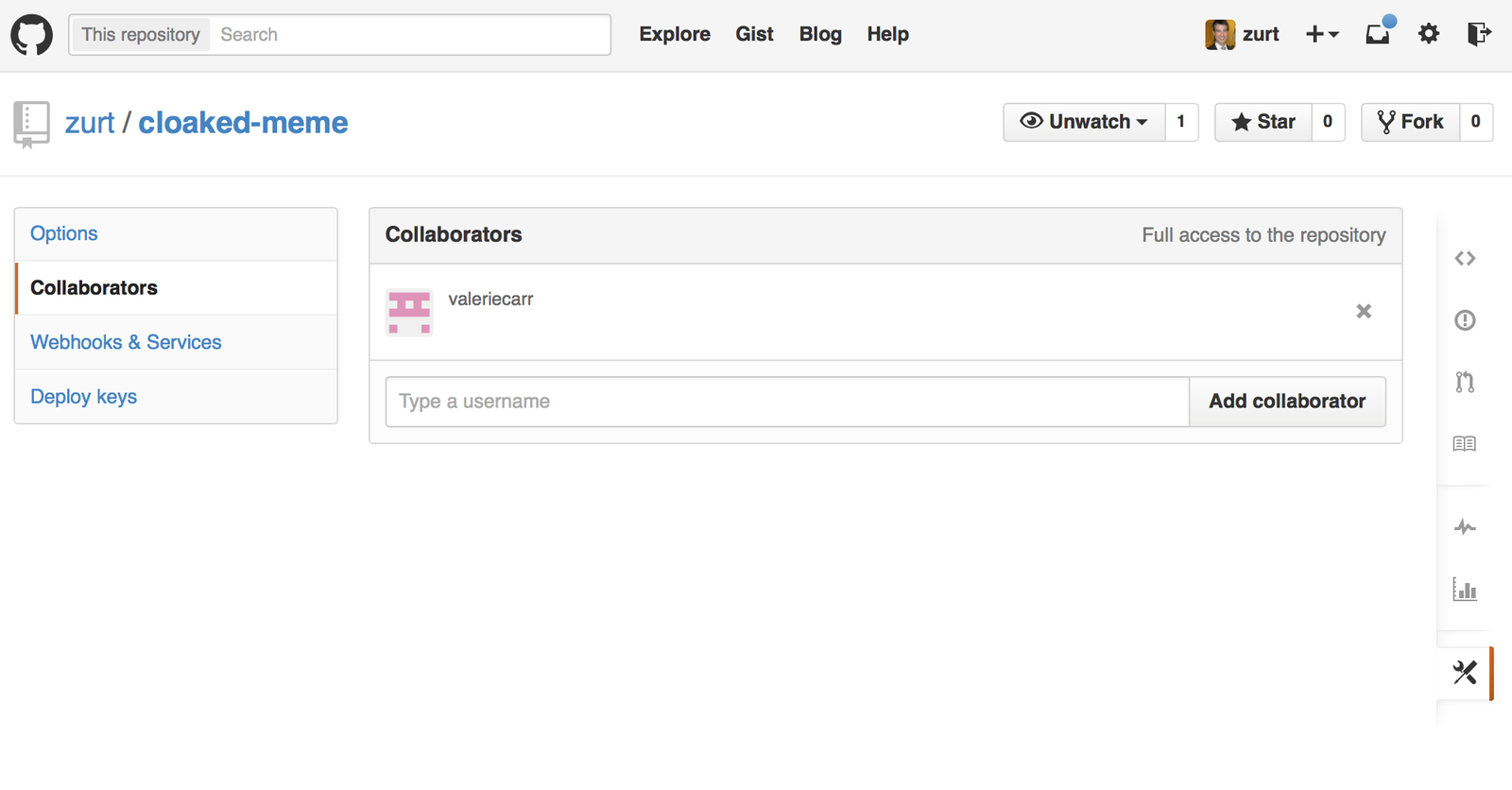

Add Collaborators

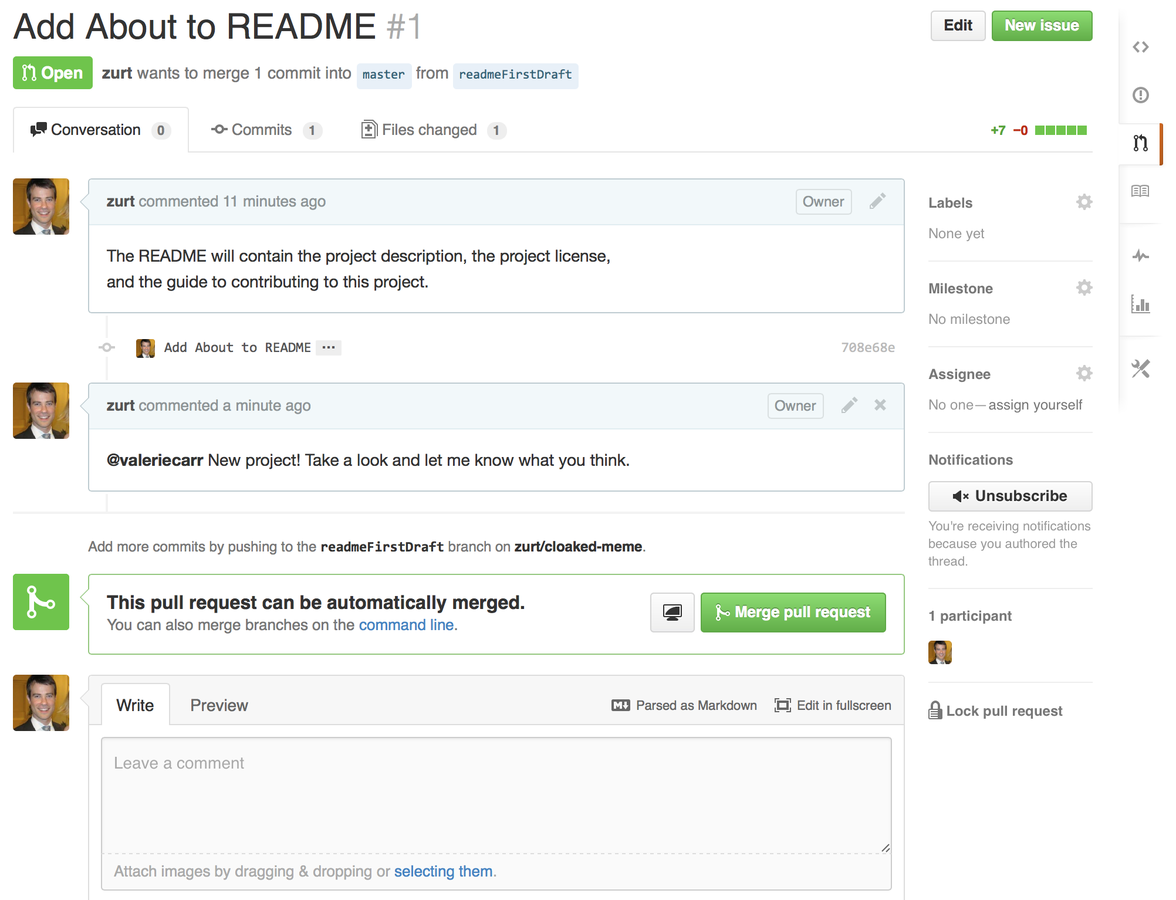

Ask for Feedback

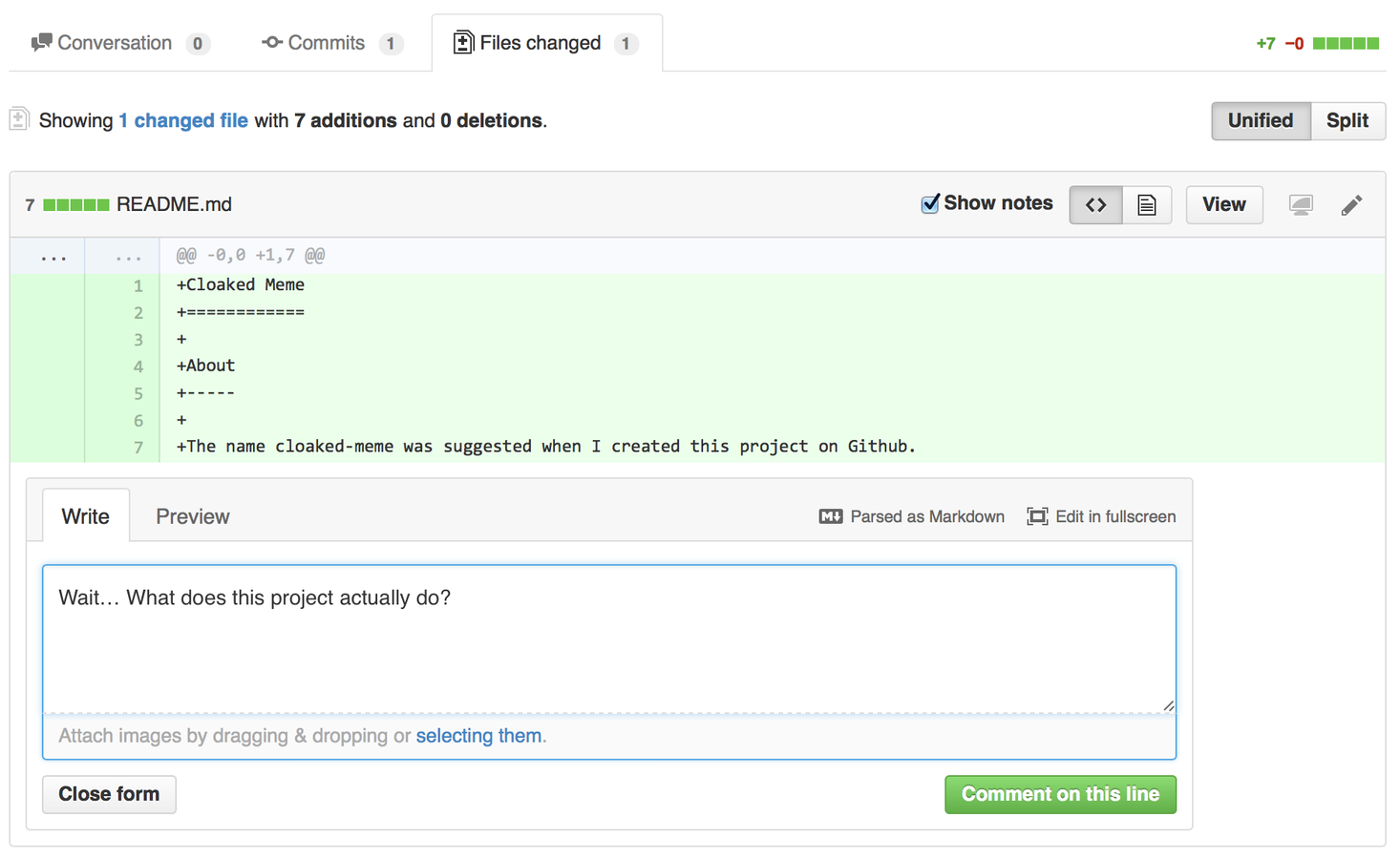

Add Comments

Responses Follow

Merge Pull Request

Merged

Back to Master

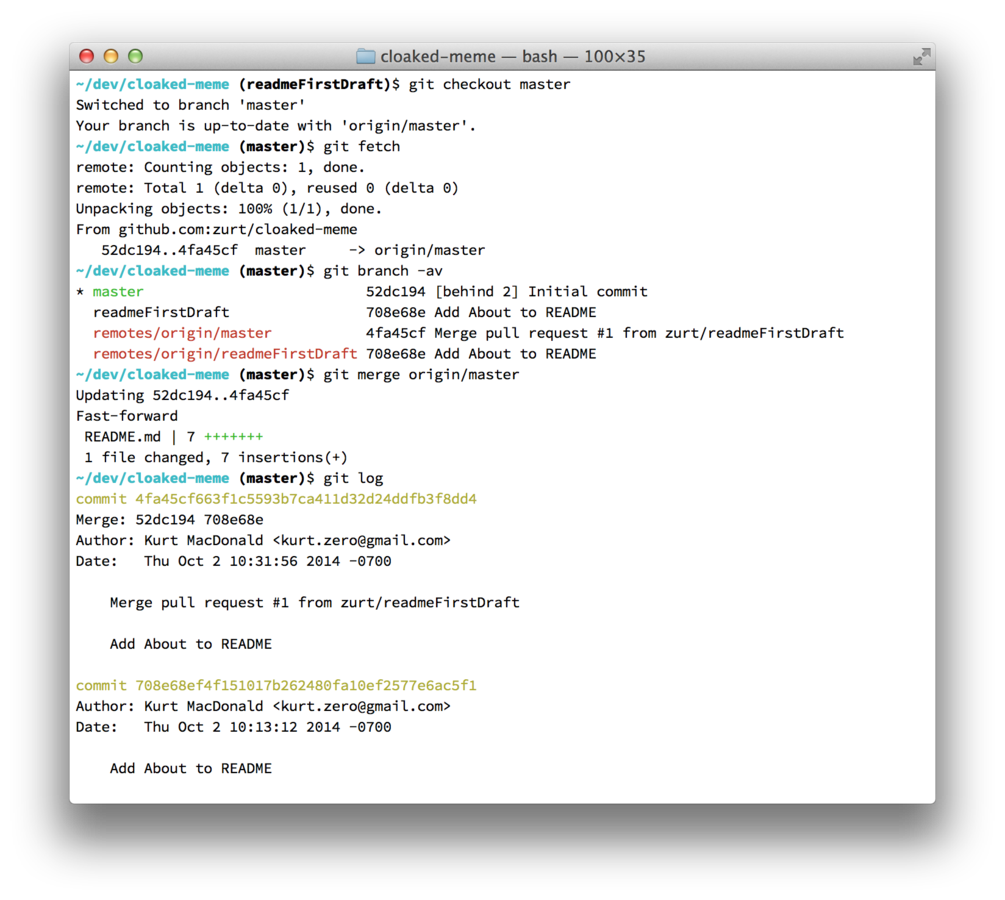

Update Local Repository

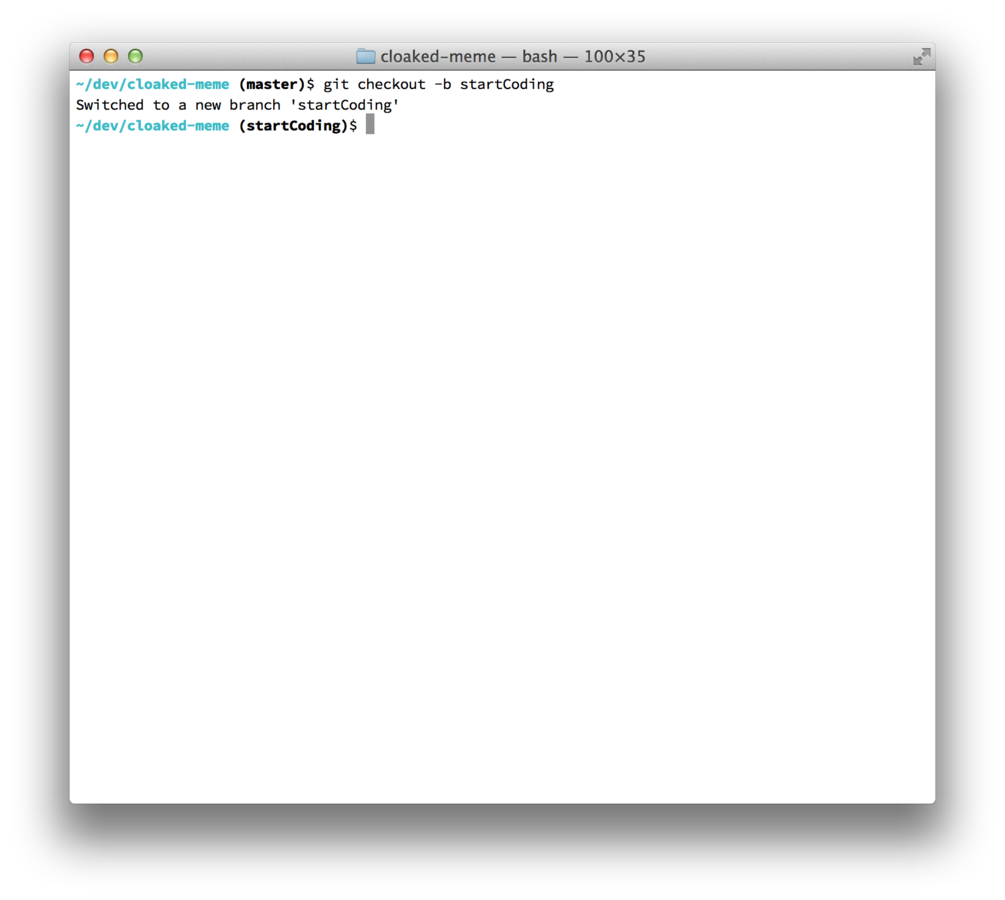

New Branch From Master

Issues

Track bugs and features.

Gists

Sharing snippets of code.

Existing code? What to do?

“Do it now.”

To Git and GitHub

cd /project

git init

git add .

git commit -m "Put project in git"

git remote add origin <remote repository URL>

git push origin master

- Create new project on GitHub.

- Add your project to Git and push:

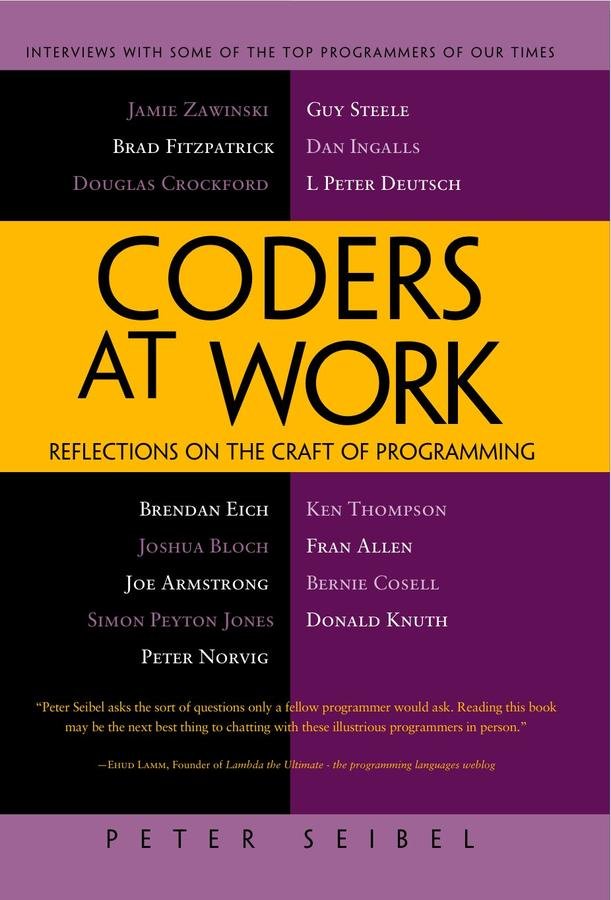

code

reading

One of the things I’ve been pushing is code reading. I think that is the most useful thing that a community of programmers can do for each other—spend time on a regular basis reading each other’s code.

Crockford: At each meeting, someone’s responsible for reading their code, and they’ll walk us through everything, and the rest of us will observe. It’s a really good chance for the rest of the team to understand how their stuff is going to have to fit with that stuff.

We get everybody around the table; everybody gets a stack of paper. We also blow it up on the screen. And we all read through it together. And we’re all commenting on the code as we go along. People say, “I don’t understand this comment,” or, “This comment doesn’t seem to describe the code.” That kind of stuff can be so valuable because as a programmer you stop reading your own comments and you’re not aware that you’re misdirecting the reader.

Having the people you work with helping to keep your code clean is a huge service—you find defects that you never would’ve found on your own.

I think an hour of code reading is worth two weeks of QA. It’s just a really effective way of removing errors. If you have someone who is strong reading, then the novices around them are going to learn a lot that they wouldn’t be learning otherwise, and if you have a novice reading, he’s going to get a lot of really good advice.

And it shouldn’t be something that we save for the end.

thank you

I welcome your questions, comments, and feedback.

Git Tips

- Never develop on master; always branch before you start coding.

- Show current branch in bash. (code-worrier.com/blog/git-branch-in-bash-prompt)

- Use Git tab completion. (git-scm.com/book/en/Git-Basics-Tips-and-Tricks)

- Commit messages can be more than 1 line. (tbaggery.com/2008/04/19/a-note-about-git-commit-messages.html)

-

Checkout the previous branch:

git checkout - -

Use “hunks” to create smaller commits: (bignerdranch.com/blog/using-git-hunks)

git add -p -

Show diff between last commit and staged changes:

git diff --staged -

Show all branches including remotes:

git branch -av -

View the last commit with diffs:

git show

Git Tips Continued

-

Customize the display of Git log:

git log --pretty=oneline -10

git log --pretty=oneline --stat

git log --pretty=format:"[%h] %ae, %ar: %s" --stat -

Browse the history of a single file in Git:

git log --follow -p filename -

List branches from newest to oldest:

git for-each-ref --sort=-committerdate refs/heads/ -

Closest thing to “undo” after `git commit --amend`:

git reset --soft HEAD@{1}

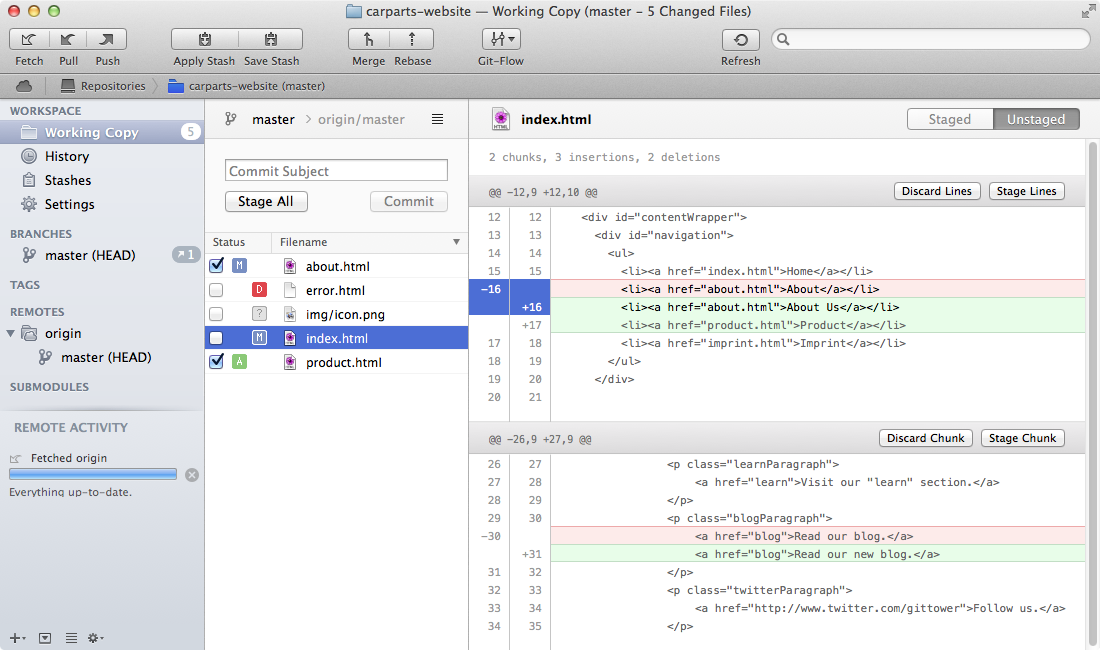

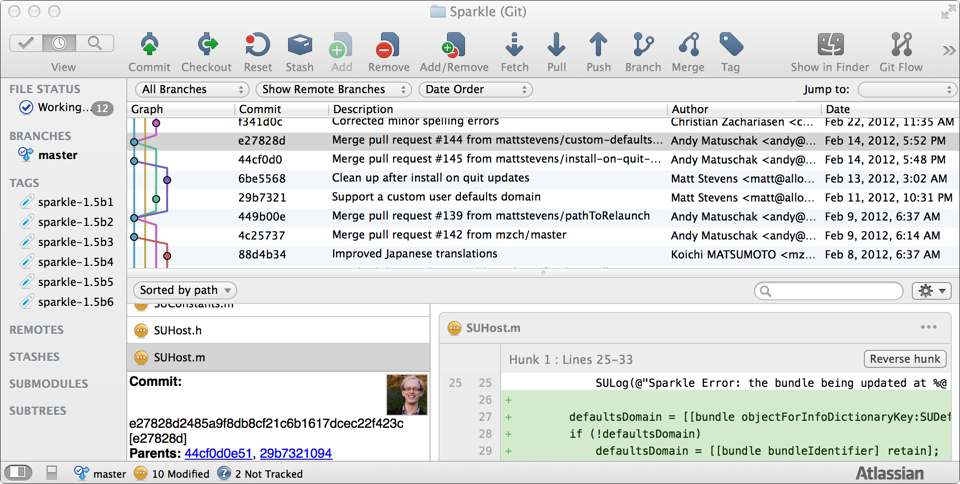

Git GUI

Changed Files

Split Diffs

Comments

Example

# Create a new branch for development.

$ git checkout -b newFeatureBranch

# Write some code.

$ git status

$ git add -p

$ git commit -m "Add foo

>

> Fixes #1138.

>

> Some additional details after one blank

> line that describe the changes."

$ git push origin HEAD:refs/for/master

# Make changes based on feedback.

$ git add -p

$ git commit --amend

$ git push origin HEAD:refs/for/master

# Make more changes based on comments.

$ git add -p

$ git commit --amend -C HEAD

$ git push origin HEAD:refs/for/master

# Move back to the master branch.

$ git checkout master

$ git fetch

$ git merge origin/master

$ git log

# Repeat.Gerrit

Workflowin Git

Whiteboard Design Sessions

* Very short

* All people working on related pieces are present

* Discuss requirements and design

* Discuss and agree on interface: data and api

* Agreement before going away to code…

* Come back together as often as necessary

Automated Tools (JavaScript)

Documenting Code

Inline documentation

Tools: YUIDoc

README.markdown

Use cases:

* describe in plain language the expected function of a program

* list steps for “happy path”

* errors conditions handled along the way

* screenshots for visual inspection and stuff that can’t be tested