Models of Lobbying

Lecture 7, Political Economics I

OSIPP, Osaka University

1 December, 2017

Masa Kudamatsu

Motivation

We have seen

how elections and legislative bargaining affect the choice of policies

But policy-making also depends on lobbying by interest groups

e.g. NRA (National Rifle Association) in U.S.

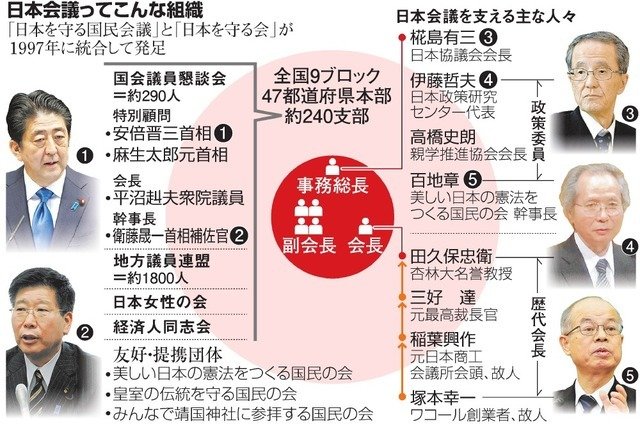

e.g. 日本会議

But policy-making also depends on lobbying by interest groups

Motivation (cont.)

Motivation (cont.)

In what way

do these interest groups

influence policy-making?

The literature (and this lecture)

almost exclusively focuses on lobbying in U.S.

Partly because good data is available

Lobbying in other countries (including Japan)

is completely an open question

Models of lobbying

There is no widely accepted model to analyze lobbying

Contest Model

(How lobbyists affect policy is blackboxed)

Existing models can be categorised as below

Quid Pro Quo

Models

Offering money to policy-makers contingent on enacted policy

Informational Lobbying

Models

Providing information on which policy benefits policy-makers

Quid Pro Quo Models

Quid Pro Quo models

Popular in the 1990s

Several variants, but they all assume

Interest groups promise to pay "bribes" to politicians

if their preferred policy is chosen

They can commit to this promise once the policy is chosen

Or politicians can commit to the policy after receiving bribes in advance

Most popular was the common agency model

Common Agency Model

also known as the menu auction model

Originally proposed by Bernheim and Whinston (1986)

as a version of the principal-agent model

with many principals and one agent

Grossman and Helpman (1994) apply this model to trade policy-making process influenced by interest groups

We follow a version used

by Section 7.3 of Persson and Tabellini (2000)

Model in a nutshell

1

Each interest group \(J\) simultaneously propose

a contribution schedule \(C^J(\mathbf{g})\), to maximize

\(\mathbf{g}\): Vector of policies

\(C^J(\mathbf{g})\): the amount of \(J\)'s contribution

if the policy-maker implements \(\mathbf{g}\)

We assume interest groups can commit to their contribution schedule proposal

\(W^J(\mathbf{g})\): \(J\)'s payoff from policies

2

Model in a nutshell

Observing \(C^J(\mathbf{g})\), the single policy-maker sets \(\mathbf{g}\) to maximize

\(V(\mathbf{g})\): the policy-maker's payoff from policies

Social welfare, if the policy-maker is benevolent

e.g.

Weighted sum of citizen payoffs, if the election is modeled as in the probabilistic voting model

How much the policy-maker can be corrupt

\(\eta \in [0,1]\): Weight on the policy-maker's own preference

e.g.

Degree of benevolence, if \(V(\mathbf{g})\) is social welfare

Equilibrium

Interest group \(J\)'s optimal contribution schedule is given by

with some \(B_J>0\)

Consequently, the policy-maker maximizes

that is, the weighted sum of payoffs with interest groups' weight being \(1-\eta\)

Applications

Trade policies (Grossman and Helpman 1994 AER)

Evidence: Goldberg and Maggi (1999 AER) and Gawande and Bandyopadhyay (2000 Restat) for U.S.

Mitra et al. (2002 Restat) for developing countries

Theoretical extensions

Citizen-candidate model (Besley and Coate 2001 Restud)

Legislative-bargaining model (Helpman and Persson 2001)

Endogenous lobby formation (Mitra 1999 AER)

Other quid pro quo models of lobbying

Legislative vote buying model of Groseclose and Snyder (1996)

Bribery contingent on voting, not the enacted policy

Applied by Diermeier and Myerson (1999 AER) to endogenize legislative committees' agenda-setting power

The poor citizens may prefer dismantling checks & balances

(i.e. legislature can veto president's policy-making)

if the rich bribes the president

Evidence against quid pro quo models of lobbying

Measuring money given by interest groups

Organizations wishing to give contributions to federal candidates

must create PACs (political action committees)

PACs must raise voluntary donations from individuals

Corporate PAC contributions: corporate managers

Labor PAC contributions: labor union members

In 2000, about 3000 PACs contributed to federal candidates

1,400 associated with corporations

240 associated with labor unions

Panel regression

% of times legislator \(i\) votes in line with Chamber of Commerce during Congress period \(t\)

Amount of contributions from corporate PACs

received by legislator \(i\) during Congress period \(t\)

Amount of contributions from labor PACs

received by legislator \(i\) during Congress period \(t\)

If contributions are effective, we should see

Results

| FE estimates | Mean [s.d.] | |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate Contributions |

0.02 | 6.53 [5.99] |

| Labor Contributions |

-0.13 | 4.48 [5.39] |

| # of observations | 3400 |

Both estimates are not significantly different from zero

Dependent variable: % of times voting for Chamber of Commerce

1 s.d. increase in contributions raise the voting score only by

0.12 ppt (corporate) / -0.70 ppt (labor)

Source: Table 2 of Ansolabehere et al. (2003)

(Standard errors are not reported in the paper...)

Taking stock

Although it's not causal, available evidence is inconsistent with the quid pro quo models' assumption that politicians receive money in return for their policy choice

Contest Model

We follow a version used by Kang (2016 Restud)

Motivation

Campaign contributions are not the only way for the interest group to interact with politicians

Interest groups can hire lobbyists to contact with politicians

Money involved

in U.S. in 2012

Campaign contributions

Interest

Groups

Politicians

Lobbyists

Hire

?

$750,000,000

$3,500,000,000

Source: de Figueiredo and Richter (2014), p. 165

Question

Do lobbying expenditures influence politicians' choice of policies?

Kang (2016 Restud) attempts to answer this question

by structurally estimating the contest model

Measuring the enactment of a policy

Collect all the bills on the energy sector

introduced during the 110th Congress

(2007-2008: last 2 years of George W Bush's 2nd-term presidency)

Including those the committees didn't submit to the floor

Divide a bill into sections

One bill may deal with several policies

A bill section deals with one specific policy

Measuring the enactment of a policy (cont.)

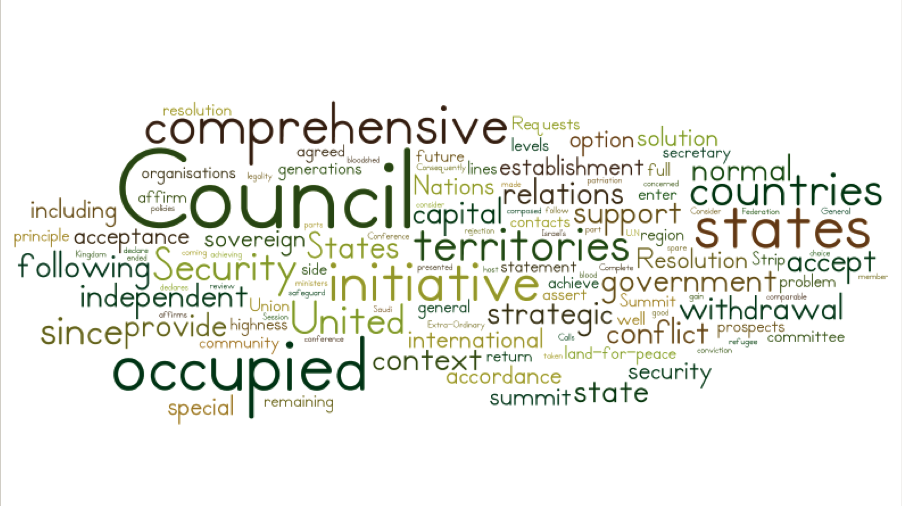

Obtain word frequencies of each bill section

Image source: khorn2.onmason.com/author/khorn2/

Measuring the enactment of a policy (cont.)

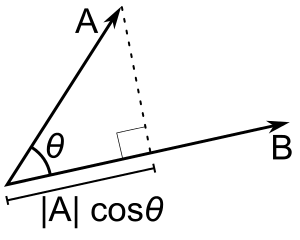

Treating word frequencies as a vector,

measure the angle between a pair of bill sections

Image source: www.mathsisfun.com/algebra/vectors-dot-product.html

Measuring the enactment of a policy (cont.)

if relative frequencies of all words are the same

if no single word is used in common

Treat bill sections as the same policy if

Then look at the status of the last bill

among all bill sections dealing with one policy

Measuring the enactment of a policy (cont.)

Bills are typically amended throughout Congress session

| Status | # of policies | % of policies |

|---|---|---|

| Enacted | 45 | 8.4% |

| Reported | 106 | 19.7% |

| Not reported | 387 | 71.9% |

Source: Table 1 of Kang (2016)

Data on the U.S. lobbying industry

Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995

requires all lobbying firms to report (twice a year):

Client names

Revenue received from each client

List of bills they lobby for/against (for each client)

Names of individual lobbyists involved for each client

Data can be downloaded at Senate Office of Public Records (SOPR)

Center for Responsive Politics summarises the data

Measuring lobbying expenditure

The lobbying industry data identify

559 firms and trade associations in the energy sector

Total lobbying expenditure: $607.9m

Median lobbying expenditure: $0.16m

Top 10% accounts for 76% of total expenditure

Source: Kang (2016), page 273

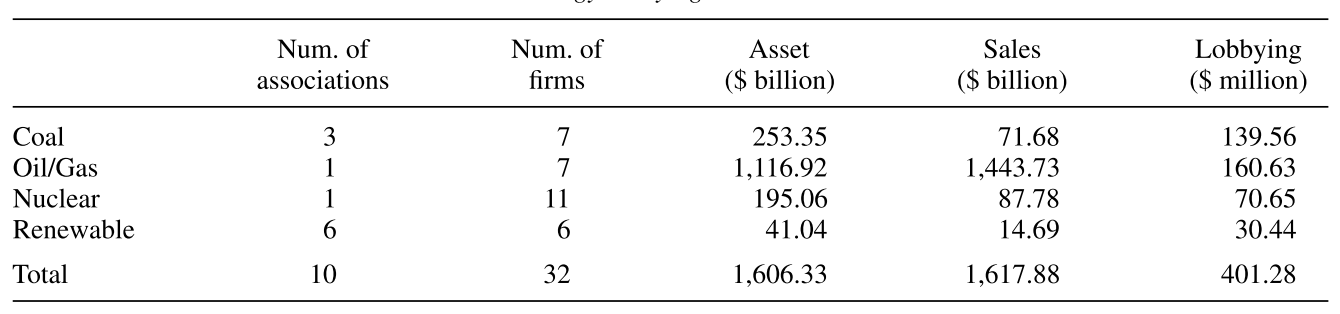

Measuring lobbying expenditure (cont.)

Source: Table 2 of Kang (2016)

Group these lobbying firms and trade associations

into four sub-sectors

Coal

Oil/Natural Gas

Nuclear

Renewable energy

Measuring which policy was lobbied

Assume a coalition lobbies for/against all policies within a bill mentioned in the dataset

% of policies each lobbying coalition participates in lobbying

| Coal | 50% |

| Oil / Natural Gas | 67% |

| Nuclear | 49% |

| Renewable | 62% |

Source: Table 3 of Kang (2016)

Data limitation & Case for structural estimation

Each coalition's lobbying expenditure is observed only in total

Use the equilibrium condition to allocate into different policies

No counterfactual to estimate the impact of lobbying expenditure

Use the model to estimate the probability of policy adoption in the absence of lobbying

Model: Players and Preference

Lobbyists of two types

Those in favor of the policy, \(l \in L_f\)

Those against the policy, \(l \in L_a\)

derive a payoff of \(v_l > 0\) if policy is adopted

derive a payoff of \(v_l < 0\) if policy is adopted

Model: Timing of Events

1

2

3

Each lobbyist simultaneously decides whether to lobby

by incurring the entry cost, \(c\)

Observing all the other lobbyists' decision on participation, each lobbyist \(l\) decides how much to spend \(s_l\)

The policy is adopted with probability

Notice this is a version of the contest success function that we saw in Lecture 6a

Model: Policy adoption probability

\(\pi\) if no one lobbies

Reflecting legislators' preference, institutional features, etc.

Policy adoption probability (cont.)

Not one even if only those in favor lobby (i.e. \(s_l=0\) for all \(l \in L_a\))

Consistent with the lobbying expenditure data for U.S.

Not zero

against

for all \(l \in L_f\)

Policy adoption probability (cont.)

We assume \(\gamma < 1\)

Consistent with the lobbying expenditure data for U.S.

Implies a larger # of participating lobbyists is more effective, holding the total amount of expenditure constant

This ensures multiple participating lobbyists in the equilibrium

Equilibrium

The lobbying expenditure game has the unique Nash equilibrium

See Appendix B of Kang (2016) for proof

The lobbying participation game has multiple equilibria

Assume that the equilibrium with the highest sum of payoffs of all players is selected

Structural estimation

Pick the parameters of the model (\(\beta_f, \beta_a, \gamma\), etc.)

to maximize the likelihood of observing

Whether each lobbyist participates for

Total expenditure by each lobbyist over all policies

Whether each policy is adopted

Findings

95% confidence interval: [0.00021, 0.00415]

Impact of lobbying on policy adoption rate

Average return to lobbying expenditure

\(\tilde{\mathbf{s}}_{-l}\) is the other lobbyist expenditure as the equilibrium response to \(s_l=0\)

For coal coalition: \(v_l\) is $802 million; \(s_l\) is $291,588

Taking stock

Probability of policy adoption changes very little due to lobbying

But return to lobbying exceeds 100%

because of a very high gain from policy adoption

How lobbyists affect policy-making, however, is blackboxed

Informational lobbying models

Motivations

One role of lobbyists is believed to be

the provision of information to politicians

Politicians do not know what policies benefit citizens the most (and themselves through their re-election probability)

Interest groups have such information

They may want to lobby themselves or hire lobbyists

to convey such information to politicians

Models of informational lobbying

Can be categorized into two groups

1

2

Cheap talk

Costly or verifiable information

Lobbying with verifiable information

Model

Players: Policy-maker \(L\) and two interest groups \(j \in{A,B}\)

Policy: \(D \in \{a, b\} \)

Preference over policy:

Policy-maker \(L\): \(V_L\) if \(D=s\); 0 otherwise

Group \(A\): \(W_A\) if \(D=a\); 0 otherwise

Group \(B\): \(W_B\) if \(D=b\); 0 otherwise

State of the world: \(s \in \{a, b\} \)

i.e. Which policy benefits citizens more

Prior: \(\Pr(s=a) = p < 1/2 \)

Model: Signal on the state of the world

Interest groups can invest \(C_j\)

to acquire the signal, \(\sigma\), on the state of the world

i.e. the signal is informative (q>1/2) but not fully accurate (q<1)

Timing of events

Groups \(A\) and \(B\) simultaneously decide whether to acquire signal on the state of the world, \(\sigma\in\{a,b\}\), at the cost of \(C_j\)

1

Policy-maker \(L\) observes the decisions by \(A\) and \(B\), but not the acquired information, \(\sigma\)

2

Groups \(A\) and \(B\) simultaneously decide whether to send a message \(m_j\in\{a,b\}\) to \(L\)

3

Observing messages \(m_a\) and \(m_b\), \(L\) decides whether to learn the state of the world on his/her own at the cost of \(c\)

4

\(L\) decides which policy to implement, \(a\) or \(b\)

Group \(j\) gets punished by fine \(f\) if \(m_j \neq s\)

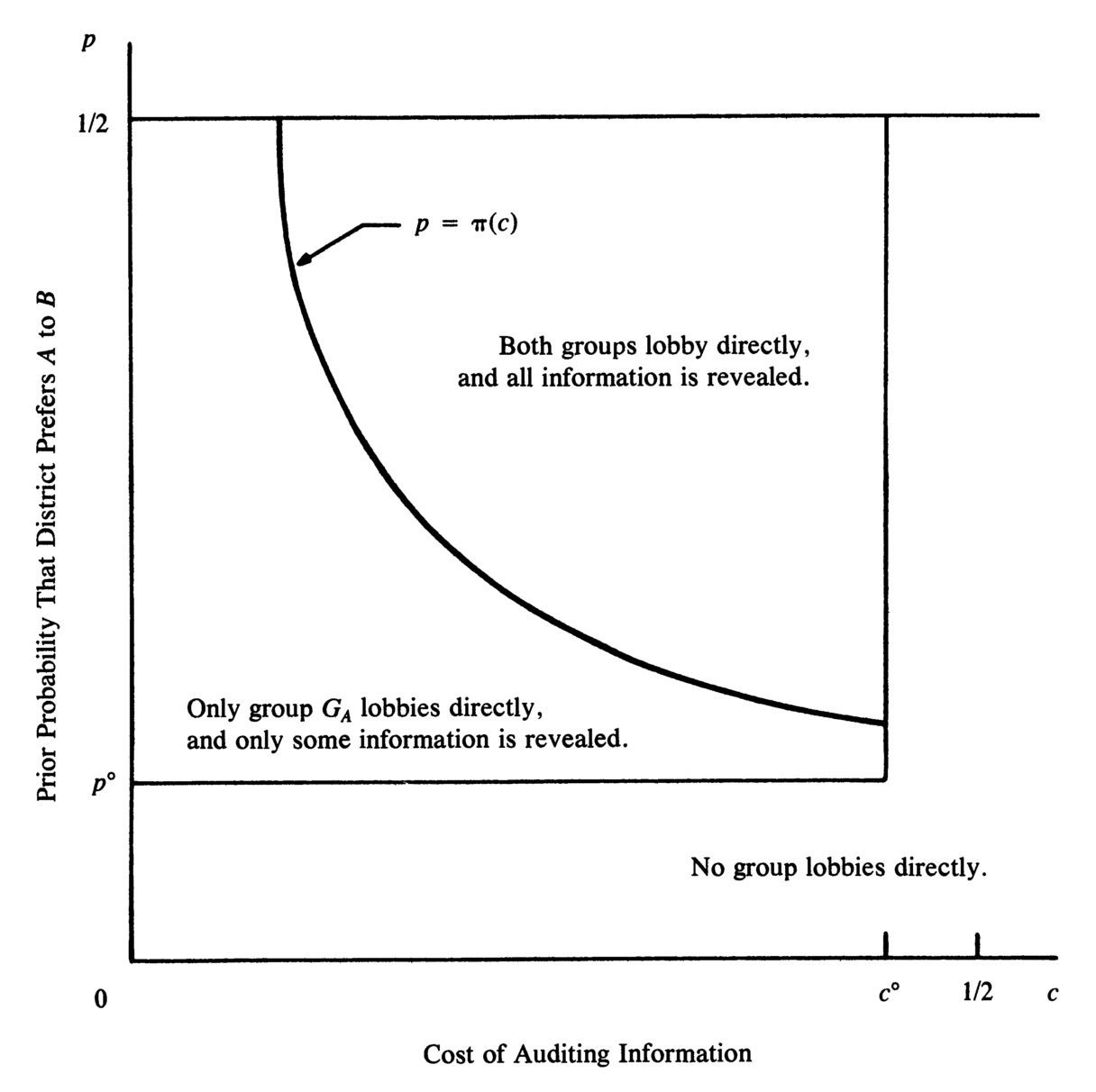

Results

Source: Figure 1 of Austin-Smith and Wright (1994)

Application

Propose a similar model of informational lobbying

(which incorporates the legislative bargaining model)

to explain why

lobbying activities are less prevalent in parliamentary democracies

Cheap Talk

We follow a simpler exposition

by Chapter 4 of Grossman and Helpman (2001)

Model

One-dimensional policy \(p\)

Which policy is desirable for the policy-maker depends on the state of the world, \(\theta\), observed only by interest group(s)

Policy-maker's payoff:

i.e. The value of \(\theta\) is the best policy

Interest group's payoff:

\(\delta > 0\) is the bias in the group's policy preference

Players: Policy-maker and Interest group

Timing of Events

1

2

3

4

Nature picks the value of \(\theta\) according to its distribution \(F(\theta)\)

Interest group sends a message \(\sigma\)

Interest group observes \(\theta\), but policy-maker doesn't

Which may or may not be the same as \(\theta\)

Policy-maker updates their belief on \(\theta\), denoted by \(\tilde{\theta}\)

by observing the message \(\sigma\)

5

Policy-maker chooses the policy \(p\)

Equilibria

In cheap talk games,

there are multiple Perfect Bayesian Nash equilibria

One of such is that policy-maker does not believe the message is true (known as the "babbling equilibrium")

See Chapter 18 of Tadelis (2013) for detail

But if the bias \(\delta\) is small enough,

there exists an equilibrium where interest groups report the true \(\theta\) and the policy-maker believes it

We illustrate this with a simple two state case

If there are two states of the world

Suppose \(\theta \in \{\theta_L, \theta_H\} \), with \( \theta_H>\theta_L \)

When does the interest group has no incentive to lie?

Suppose the policy-maker believes the interest group's message

When \(\theta=\theta_H\)

telling a lie

telling

the truth

If there are two states of the world

Suppose \(\theta \in \{\theta_L, \theta_H\} \), with \( \theta_H>\theta_L \)

When does interest group has no incentive to lie?

Suppose the policy-maker believes the interest group's message

When \(\theta=\theta_L\)

telling a lie

telling

the truth

Tell the truth if

With continuous states of the world

The condition for not telling \(\theta_1\) when \(\theta=\theta_2 \)

Consider a pair of two values of \(\theta\), (\(\theta_1, \theta_2) \) with \(\theta_1 < \theta_2\)

does not hold for all pairs of \(\theta\)

Full information revelation cannot be an equilibrium

With continuous states of the world

Instead, a message like

\(\theta\) is in the range between \(\theta_L\) and \(\theta_H\)

can be an equilibrium if \(\delta\) is sufficiently small

If we suppose the uniform distribution of \(\theta\)

Then policy-maker chooses policy \(\frac{\theta_L+\theta_H}{2}\)

(i.e. the expected value of \(\theta\) given the message)

See Section 4.1.4 of Grossman and Helpman (2001)

With two interest groups of opposite bias

Krishna and Morgan (2001) extend the cheap talk model

by adding one more message sender (i.e. two interest groups)

Denote each group's bias by \(\delta_1, \delta_2\)

Then if \(\delta_1 < 0 < \delta_2\) (i.e. two interest groups have opposite bias)

the policy-maker may learn more by listening to both,

instead of listening to only one of them

With two interest groups of opposite bias (cont.)

Group 1 sends a message whether \(\theta \leq \bar{\theta}_1\)

Group 2 then sends a message whether \(\theta \leq \bar{\theta}_2 (< \bar{\theta}_1)\)

Policy-maker, updating the belief, sets the policy

With two interest groups of opposite bias (cont.)

(2) Group 2 is indifferent between policies

For this to be an equilibrium:

(1) Group 1 is indifferent between policies

&

when \(\theta = \bar{\theta}_1\)

&

when \(\theta = \bar{\theta}_2\)

Such a pair of \(\bar{\theta}_1, \bar{\theta}_2 \) can exist when \(\delta_1<0<\delta_2\)

Evidence on informational lobbying

Data on the U.S. lobbying industry

Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995

requires all lobbying firms to report (twice a year):

Client names

Revenue received from each client

List of bills they lobby for/against (for each client)

Names of individual lobbyists involved for each client

Data can be downloaded at Senate Office of Public Records (SOPR)

Center for Responsive Politics summarises the data

Data on the U.S. lobbying industry (cont.)

Collection of biographies of lobbyists

compiled by Columbia Books and Information Services

Of which about 17,000 can be matched in www.lobbyists.info

About 37,000 lobbyists for 1999-2008 in the SOPR data

Source: Bertrand et al. (2014), p. 3889

Measuring lobbyists' expertise

From the SOPR data:

Obtain revenues a lobbyist earns from each policy issue

(see next slide for how)

1/4 of lobbyists are specialists, defined this way

Those with political experiences are less likely to be specialists

Define a specialist lobbyist as the one whose revenue from one policy issue exceeds 25% of his/her total revenue

Source: Bertrand et al. (2014), pp. 3897-3900

Measuring each lobbyist's expertise (cont.)

(lobbyist l's revenue from policy issue i) is obtained by

where VilrtV_{ilrt}Vilrt is the revenue for lobbyist lll for issue iii

from client rrr in year ttt, which in turn given by

VrtV_{rt}Vrt Lobbying firm revenue from client rrr in year ttt

IrtI_{rt}Irt # of issues the lobbying firm worked for client rrr in year ttt

LrtL_{rt}Lrt # of lobbyists working for client rrr in year ttt

(All obtained from the SOPR dataset)

Measuring lobbyists connected to politicians

For each lobbyist in the SOPR data

obtain his/her campaign contributions to any politician

from the Federal Election Commission data

If a lobbyist makes one contribution to a politician

define this lobbyist as connected to the politician

Empirical specification

\(S_{ptj}\): Share of opposite party lobbyists of type \(j\) connected to politician \(p\) for congress period \(t\)

\(j\): Indicator of lobbyists being specialist

If lobbyists provide information to politicians, we should see

This cannot be explained by quid pro quo models of lobbying

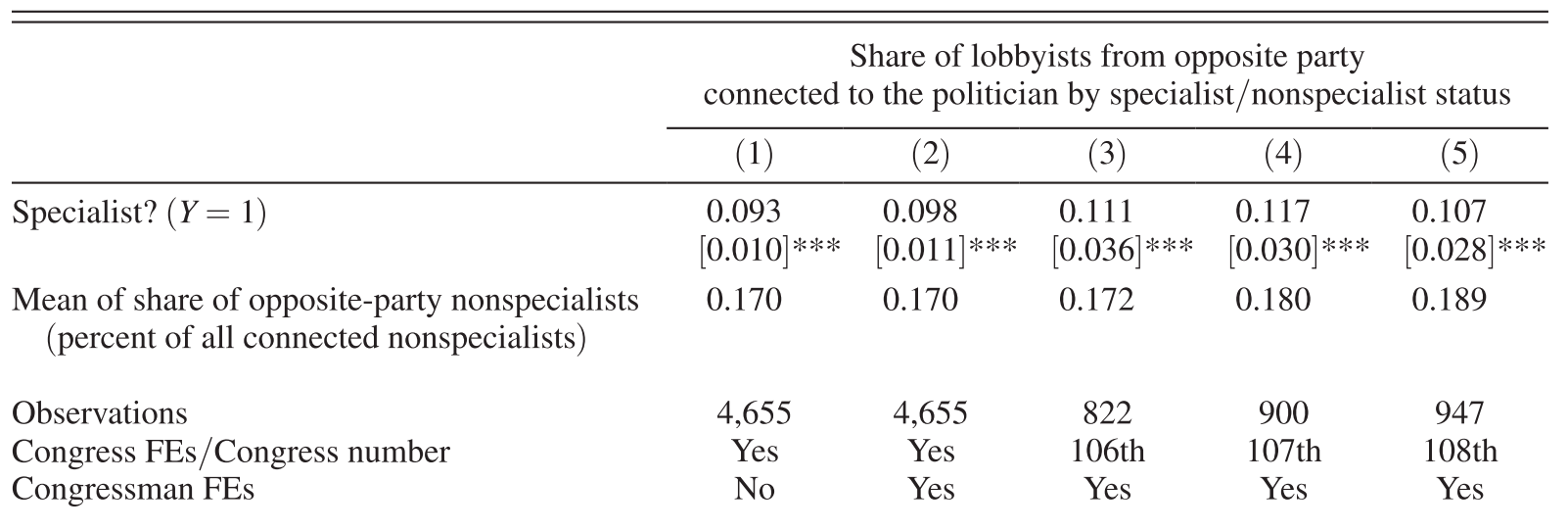

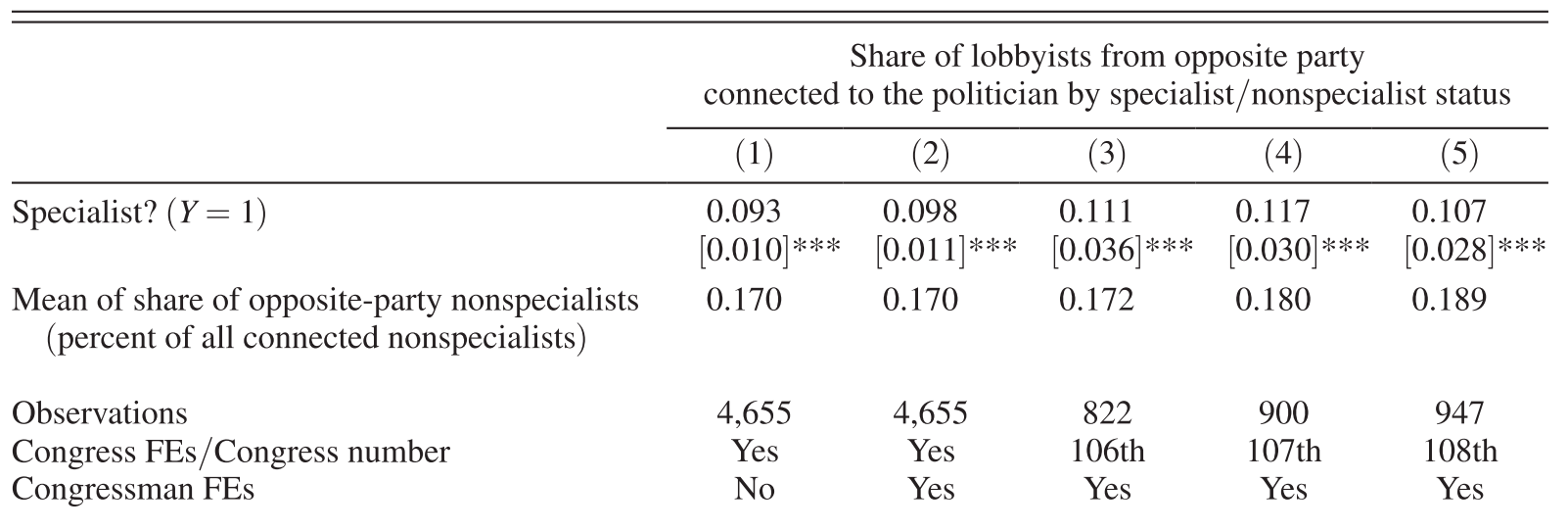

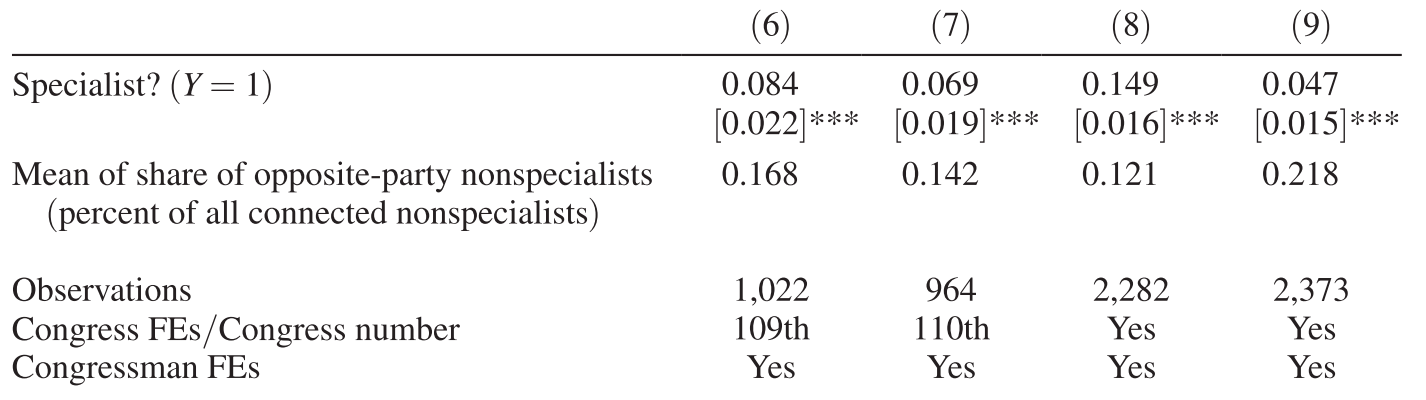

Results

Source: Table 7 of Bertrand et al. (2014)

% of opposite party lobbyists

17%

among non-specialists

27%

among specialists

vs

Note: Standard errors clustered at the politican level are reported in brackets

Results

Source: Table 7 of Bertrand et al. (2014)

Democrat

politicians

Republican

politicians

Not driven by particular congress periods

Not driven by either of the parties

Note: Standard errors clustered at the politican level are reported in brackets

Summary

Lesson #1

The quid pro quo view of lobbying seems unlikely

Politicians do not appear to respond to contributions

in their policy choice

Lesson #2

Lobbying affects the probability of policy adoption only a little

But the value of a policy is so big that the return from lobbying expenditure exceeds 100%

Lesson #3

Lobbyists appear to provide information to politicians

Politicians listen to

specialist lobbyists from both sides of the political spectrum

Whole Course Summary

Which models to use?

The division-of-a-pie problem (or other multidimensional policies)

Probabilistic Voting Model

Legislative Bargaining Model

Conflict of interest between politicians and citizens

Political Agency Model

Who becomes a politician

Citizen Candidate Model

Wars, voting, lobbying

More empirical evidence needed