Music of the Chicano Movement

Lesson Hub 2:

A History of Struggle:

Precursors to the Chicano Movement

How did historical events contribute to the systemic oppression faced by members of the Mexican American community during the time of the Chicano movement?

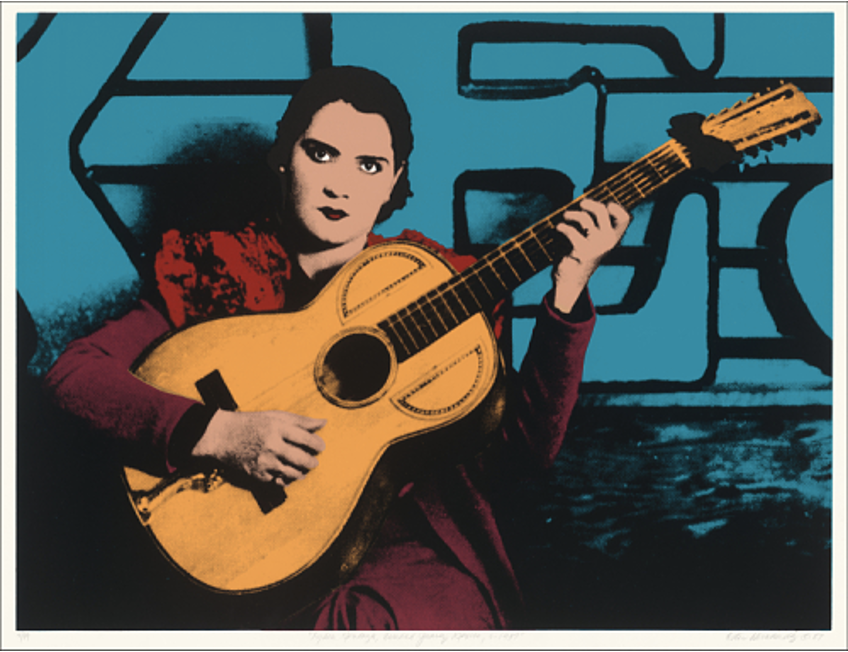

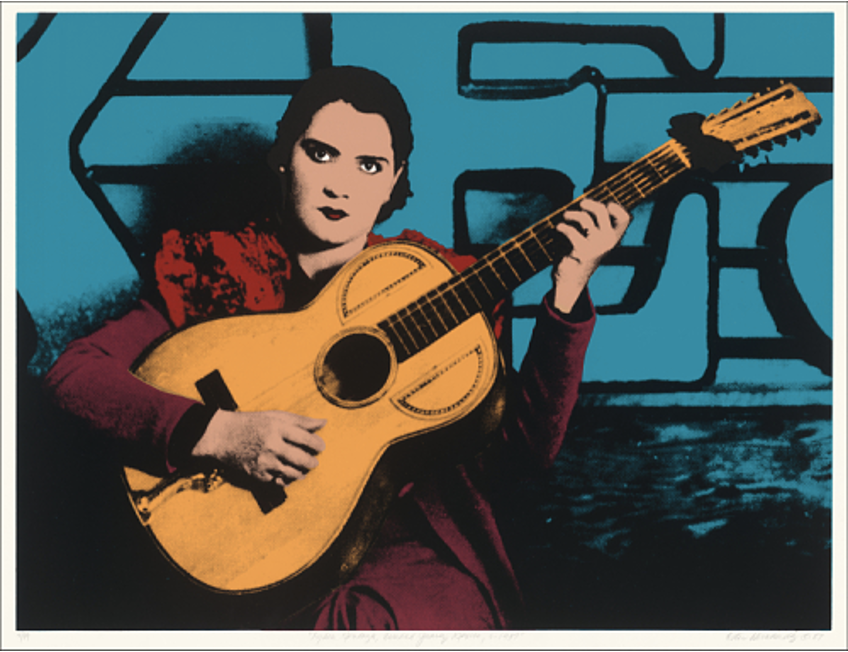

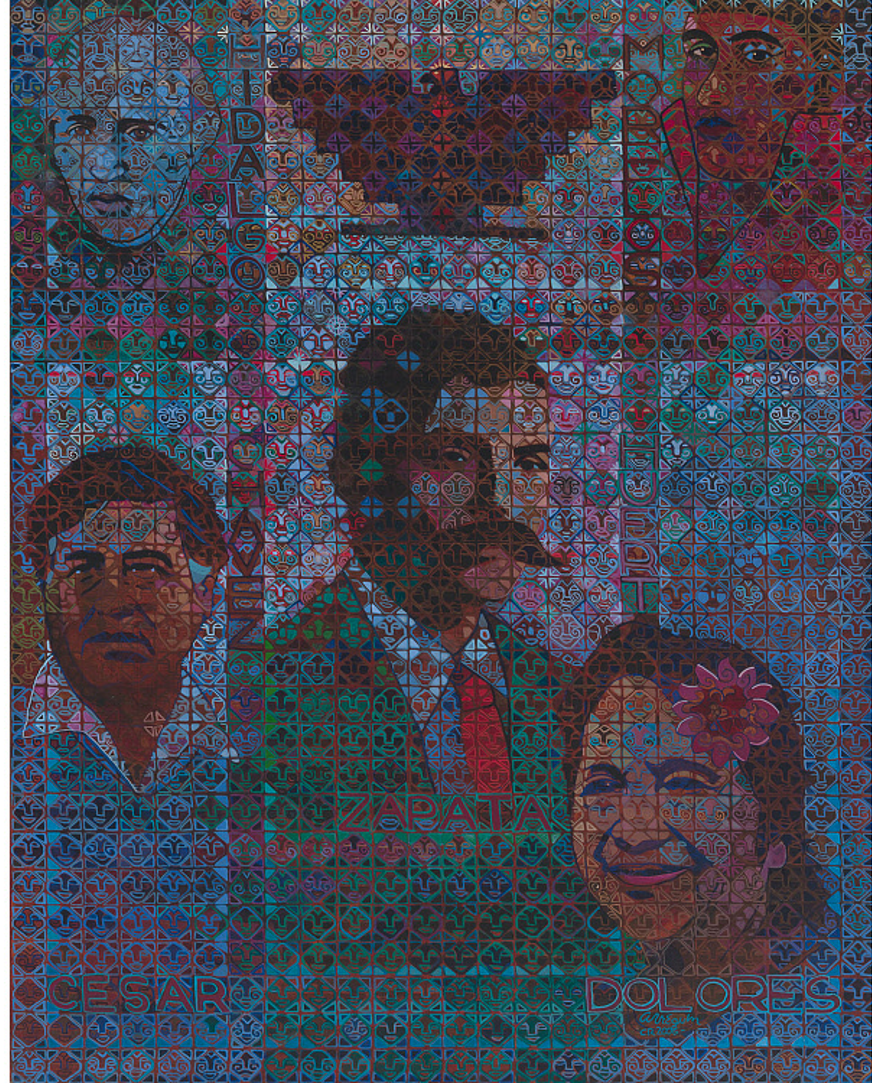

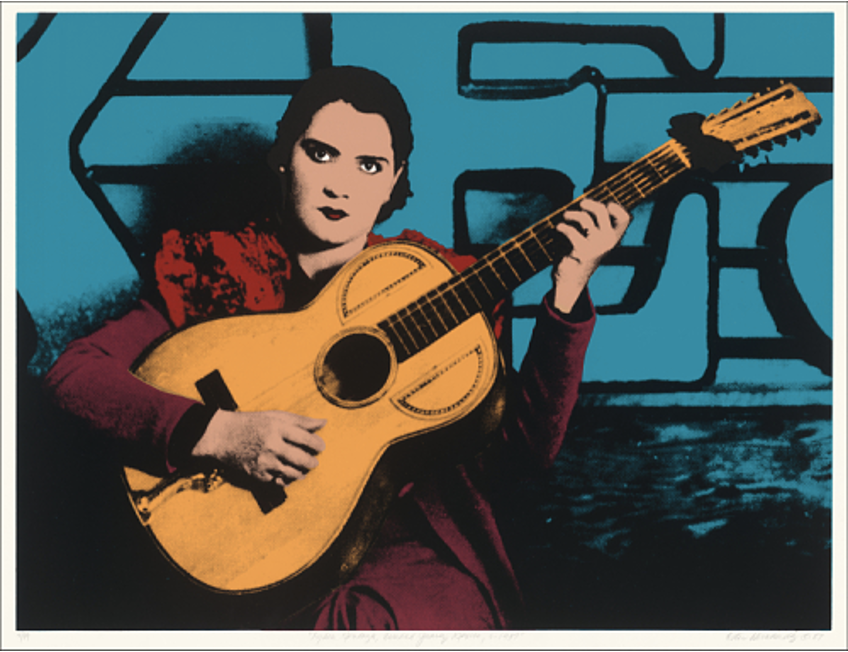

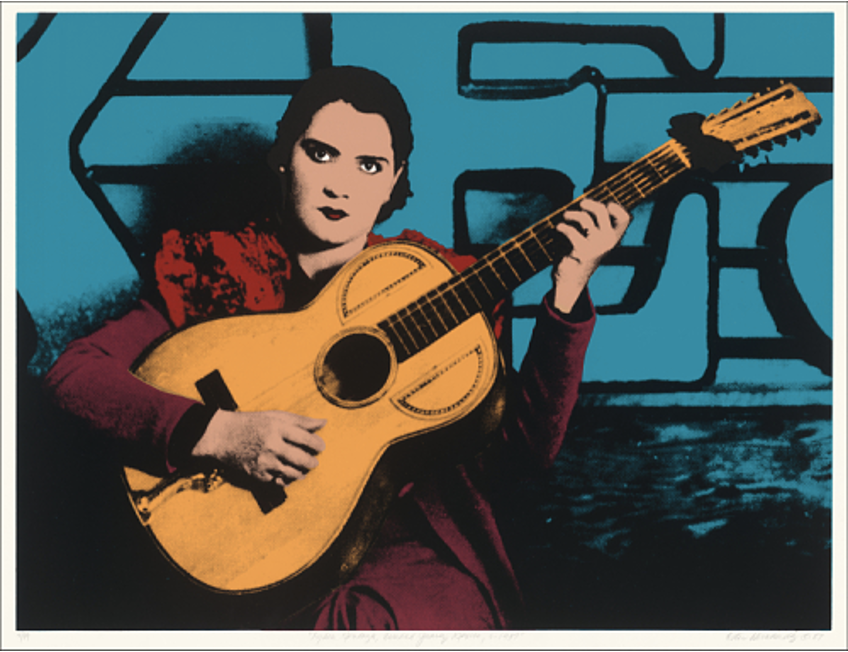

Lydia Mendoza, Ciudad Juarez, 1937, by Ester Hernández. National Portrait Gallery.

The overarching essential question for Lesson 2 is:

A History of Struggle:

Precursors to the Chicano Movement

HISTORY & CULTURE

MUSIC LISTENING

MUSIC MAKING

30+ MIN

25+ MIN

45+ MIN

A History of Displacement

Path 1

30+ minutes

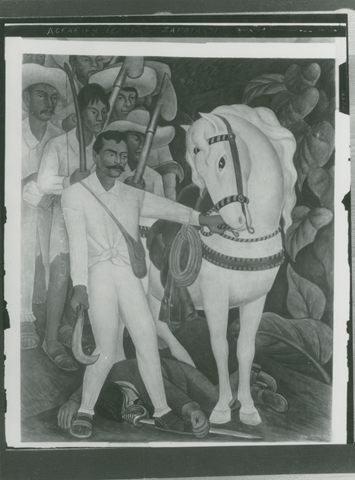

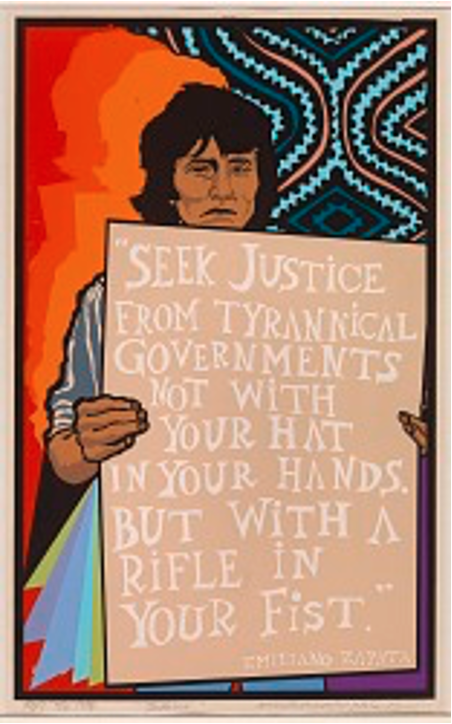

Agrarian Leader Zapata, by Diego Rivera. Photo by Peter A. Juley. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

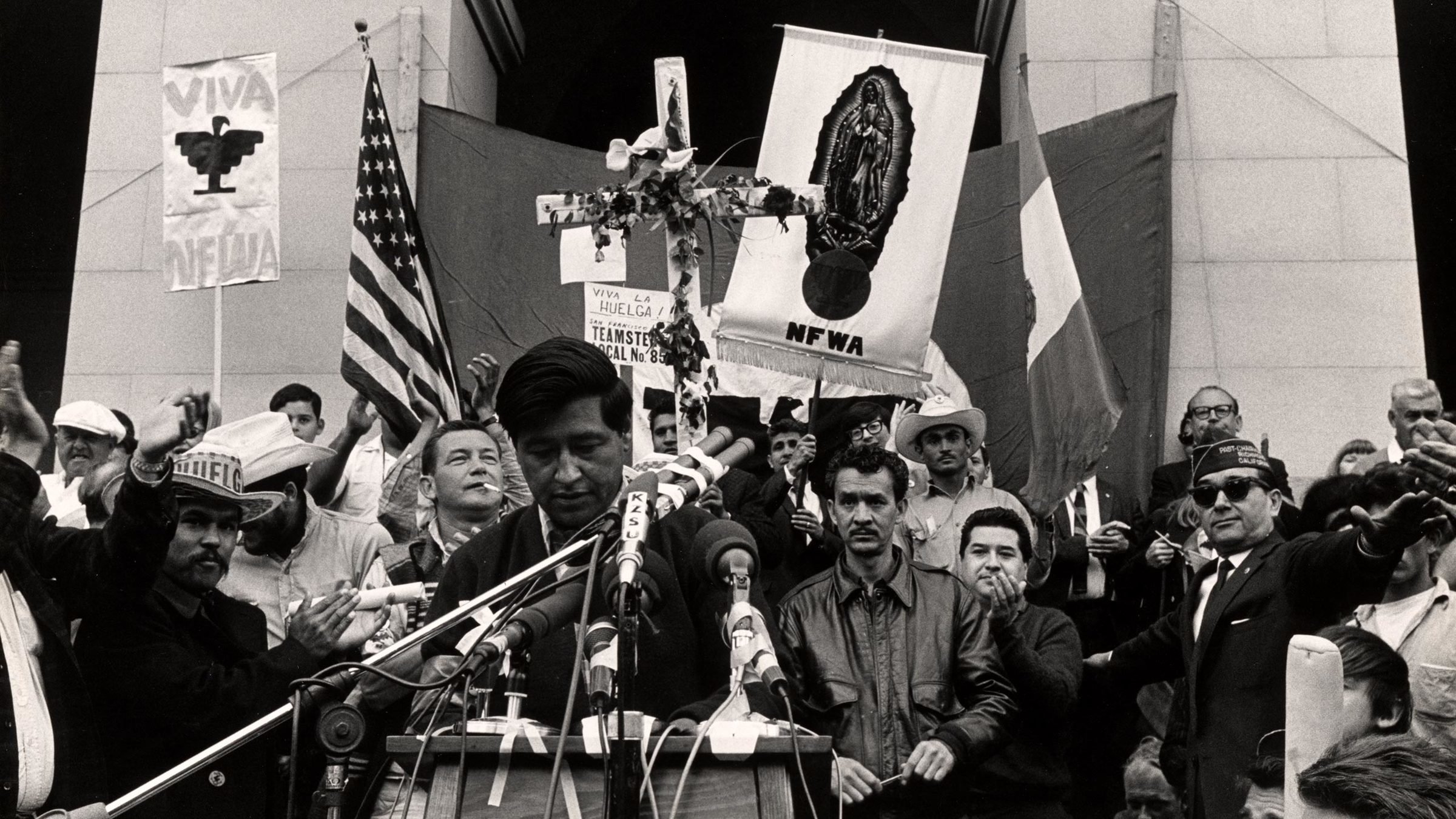

Although most of the important events of the Chicano movement took place during the 1960s and 1970s, the Mexican American community’s long history of oppression, displacement, exploitation, and discrimination began hundreds of years earlier.

What happened before the Chicano movement?

A Brief Historical Timeline

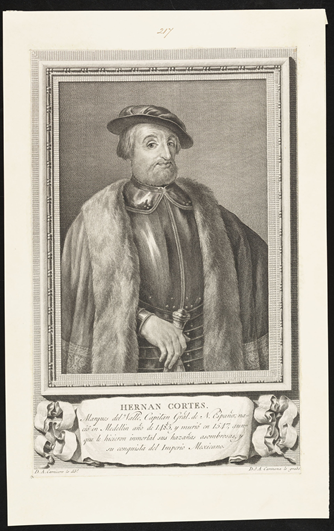

After the Spanish took control of Mesoamerica (1521), they imposed their language, institutions and religion on the native people, and exploited them for their labor.

Hernan Cortes, by D. A. Carnicero. National Museum of American History.

This history of oppression, discrimination, exploitation, and displacement can be traced back to the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in the sixteenth century.

In 1821, Mexico gained its independence from Spain during the Mexican War of Independence.

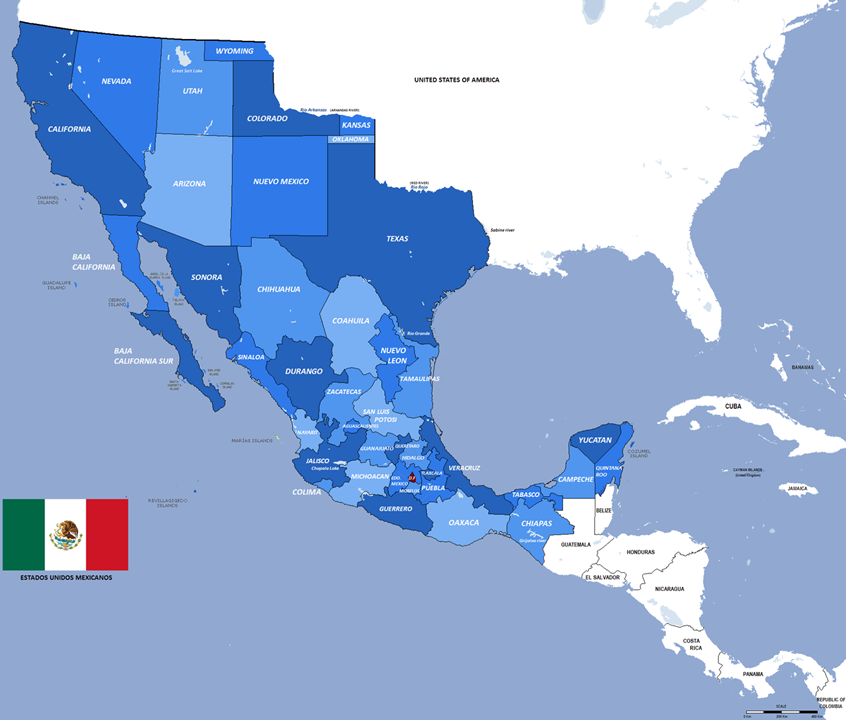

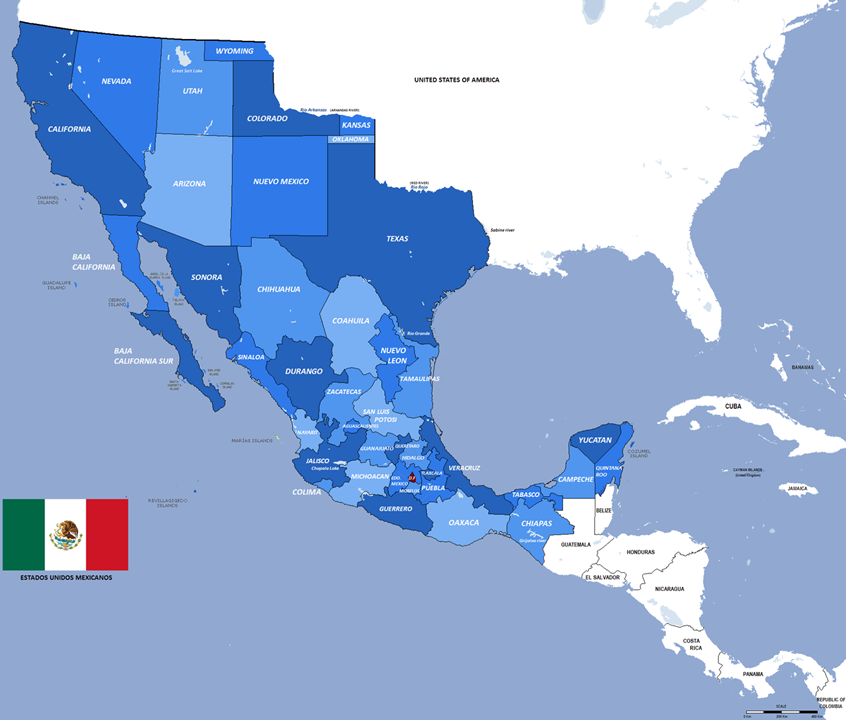

For the next 25 years, the land that comprised Mexico extended into the states that we now know as California, New Mexico, Arizona, Texas*, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming.

Mexican Independence

*Texas declared independence from Mexico in 1836, and became part of the United States in 1845

Mexico in the 19th Century

Aztlán Goal Map, created by Jaimiko. Wikimedia Commons (PD).

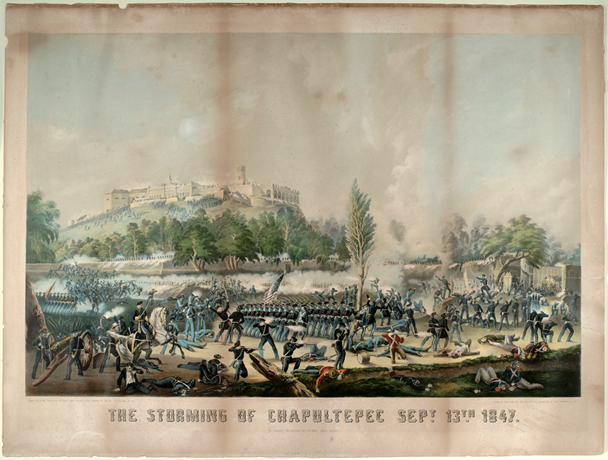

Mexican American War ...

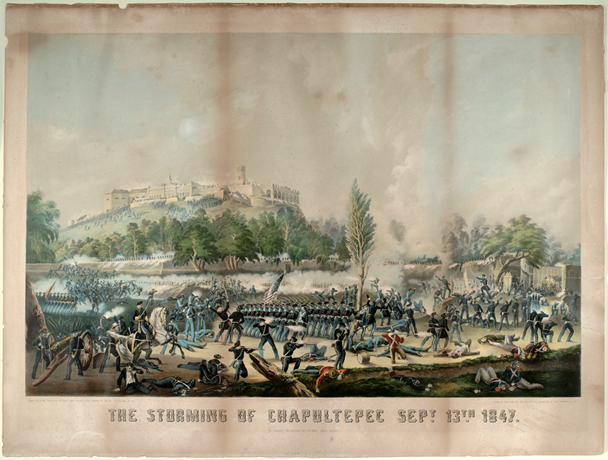

The Storming of Chapultepec, by James Walker. National Museum of American History.

... took place between 1846-1848.

The United States initiated this conflict with the intent of acquiring more land (which they did).

The End of the War

Zachary Taylor, by James Walker. National Portrait Gallery.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed at the end of the Mexican-American War.

It guaranteed US citizenship to Mexicans living in these new US territories.

It also guaranteed “rights to their land, language, religion, customs, and civil rights” (Montoya, 2016, p. 18).

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and Land Disputes

Exchange Copy of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. National Archives, PD (U.S. Code § 105).

Despite the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, many Spanish and Mexican landowners were ultimately pushed off their land by Anglo American settlers.

Land grants guaranteed by the treaty were often ignored or dismissed by the courts. In some cases, Mexican American landowners were not able to afford legal fees when land disputes arose.

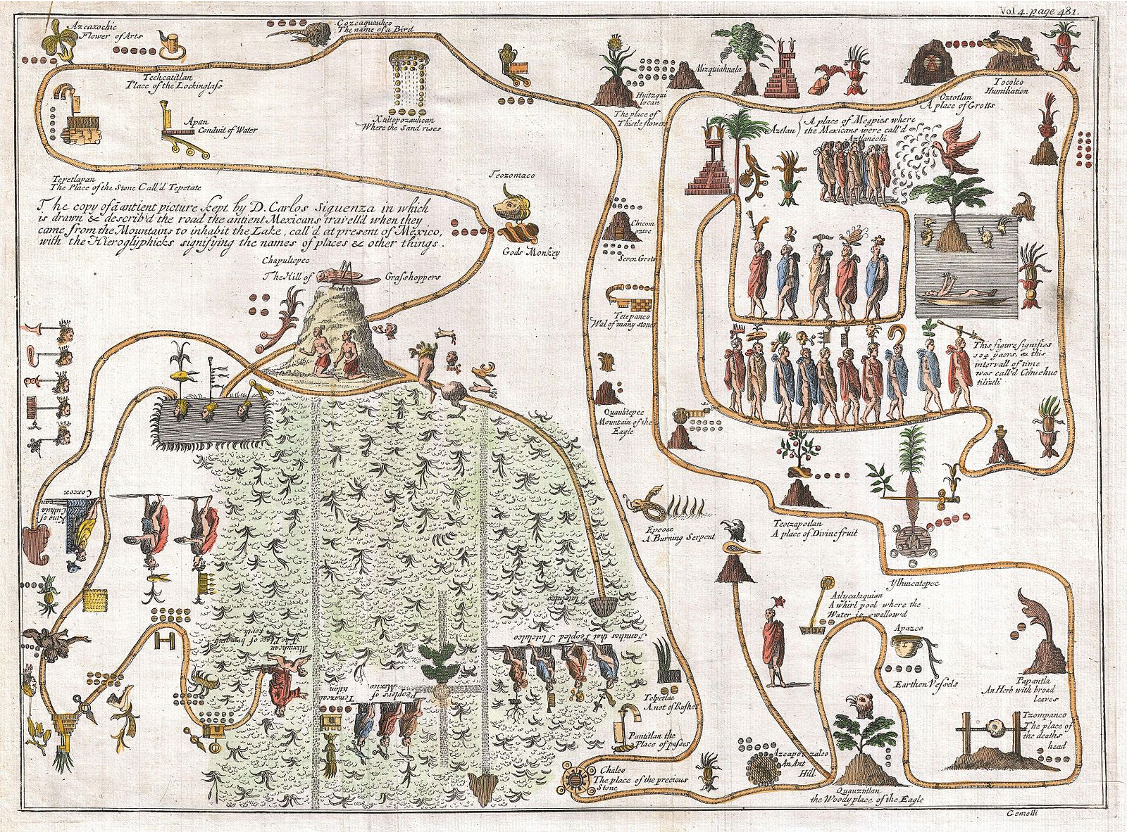

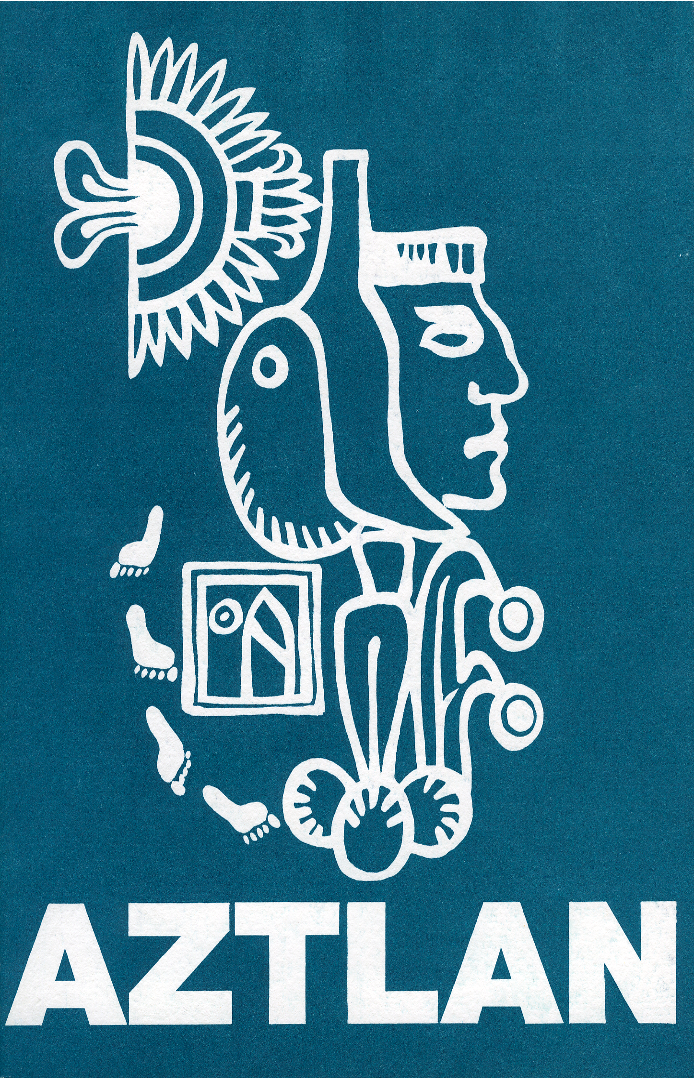

Aztlán was the name of the Aztec people’s homeland in traditional migration stories.

La tierra nueva en Aztlán, paño by Manuel Moya. National Museum of American History.

Aztlan

During the Chicano movement, activists often used the image of Aztlán to express their frustration about the broken promises of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

According to Aztec beliefs, Aztlán was located somewhere to the north of Mexico City (perhaps north of the US-Mexico border).

Chicano activists used the term Aztlán to refer to the land that Mexico lost at the conclusion of the Mexican American War.

The image of Aztlán symbolized “taking back” what they felt had been stolen from their ancestors and thus, belonged to them.

About Aztlán

Aztlán Continued…

1704 Gemilli Map of the Aztec Migration from Aztlán to Chapultepec, by Giovanni Francesco Gemilli Careri. PD-Art (PD-US-expired).

More About Aztlán

Listening Activity: "Corrido de Aztlán"

Look at the lyrics to the song “Corrido de Aztlán,” performed by Suni Paz and written by Daniel Valdez.

As you listen, underline or circle places in the lyrics that for you, represent the idea of Aztlán.

Listen to this song (in its entirety) while following along with the lyrics.

Lyrics that relate to the idea of Aztlán:

- “We declare our territory”

- “Our nation is Aztlán”

- “Fight to the death for our lands”

- “The children of the sun”

- “Down with exploitation”

- “We will protect our lands”

- “We will proclaim our lands”

"Corrido de Aztlán"

The Return to Aztlán, by Alfredo Arreguin. National Portrait Gallery.

About the Performer: Suni Paz

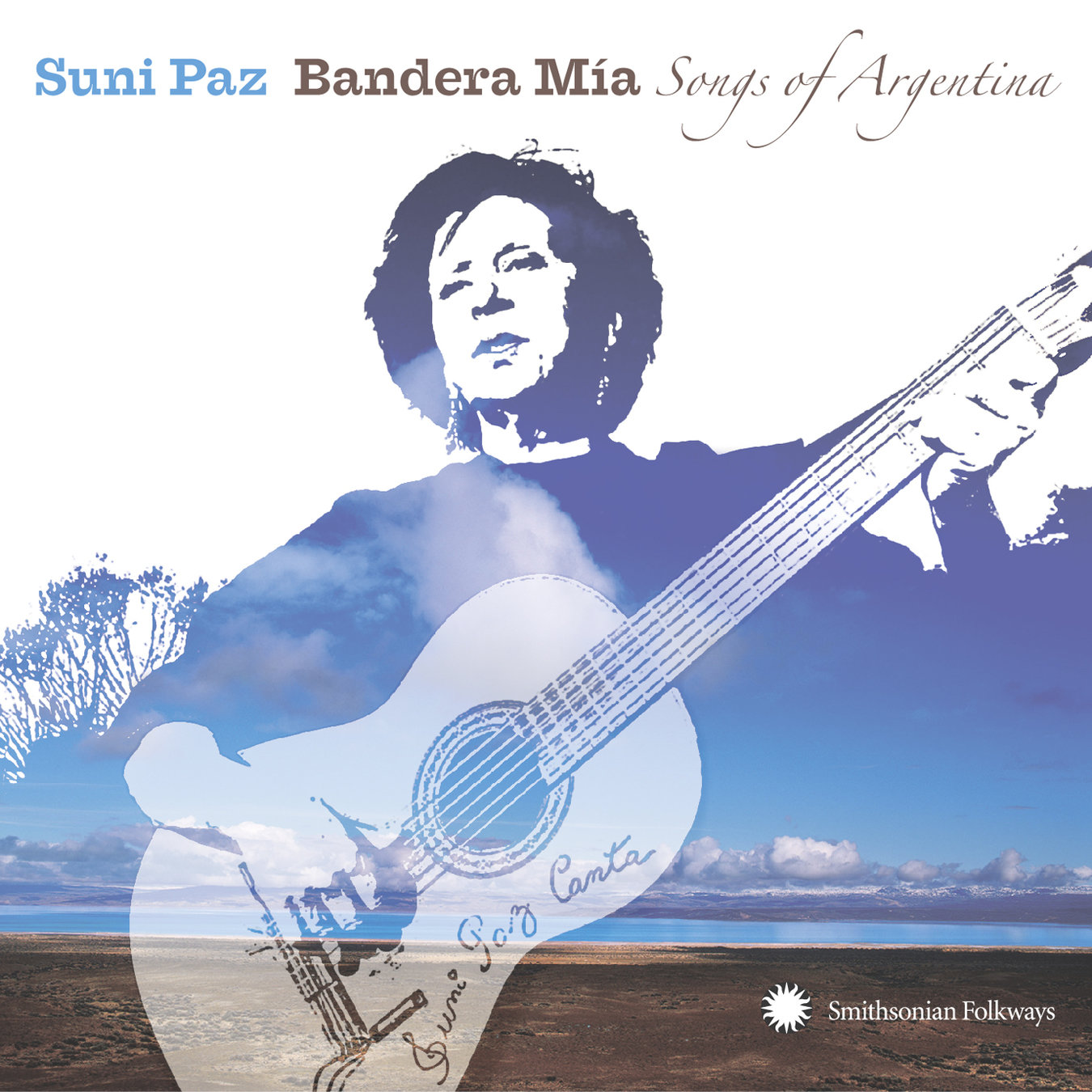

Suni Paz (the performer) is an Argentinian-born singer-songwriter who moved to the United States in 1965.

During the Chicano movement, Suni wrote and sang songs about a variety of social issues, such as the United Farmworkers Movement, Latina women’s rights, and educational access for Latino/a children.

Bandera mía, cover art by Sonya Cohen Cramer. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

The Mexican Revolution

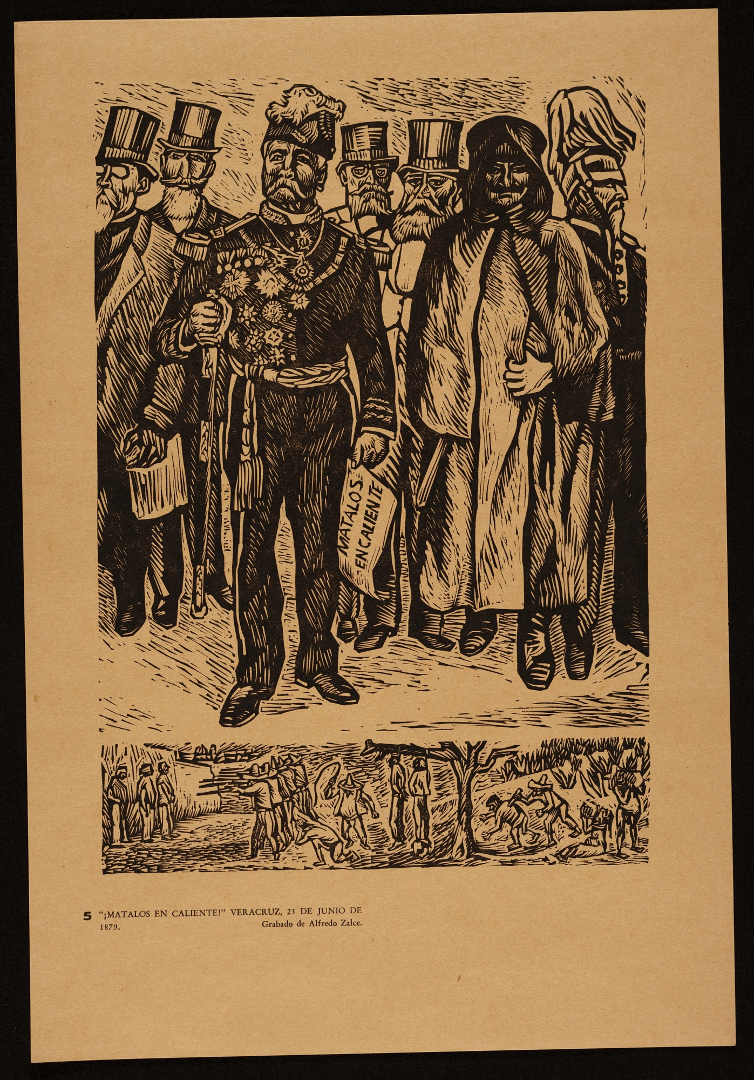

"¡Mátalos en caliente!" Veracruz, 25 de Junio de 1879, by Alfredo Zalce. Archives of American Art.

The Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) was another important historical event that had long-lasting implications for the Mexican American community, both in negative and positive ways.

During the Mexican Revolution . . .

Leaders, who stood up to oppressive authorities and fought for the rights of the poor, were celebrated as heroes.

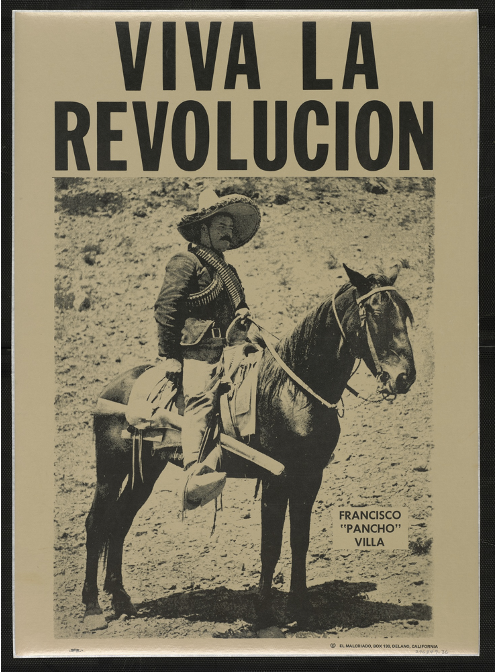

Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata were two well-known heroes of the Mexican Revolution.

Zapata, by David Alfaro Siqueiros. Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

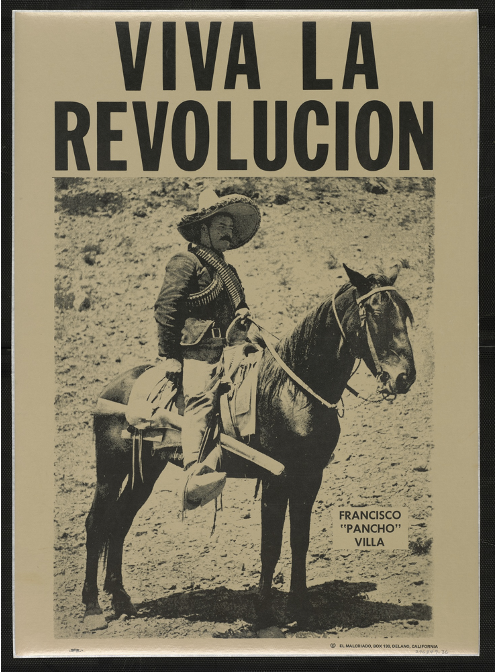

Viva la revolucion, unknown artist. National Museum of American History.

During the Chicano movement, revolutionary figures became role models and symbols.

Revolutionary Figures as Role Models

Justicia, by Amado M. Peña Jr. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

They inspired and motivated people to stand up against injustice, fight on behalf of the poor, and demand change.

Chicano/a songwriters frequently referenced figures from the Mexican Revolution in their compositions (and continue to do so).

For example, the song you just heard ("Corrido de Aztlán") references both Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata.

The Mexican Revolution and Immigration

This led to a large influx of Mexican citizens across the border and into the southwestern part of the United States.

Bridge - El Paso to Juarez, Bain News Service. Library of Congress.

During and after the Mexican Revolution, many people were forced to flee their homeland (Mexico) in order to escape the violence.

Anti-Immigrant Sentiment

This wave of immigration changed the demographics of the American Southwest, triggering much anti-immigration/anti-Mexican backlash.

Mexicans and Mexican Americans “faced some of the same systematic discrimination and racism directed towards blacks in the Jim Crow South” (Montoya, 2016, p. 21).

- Examples include lynching, vigilante justice, police brutality, segregation and prohibition of the Spanish language in schools, and deportation of people born in the U.S.

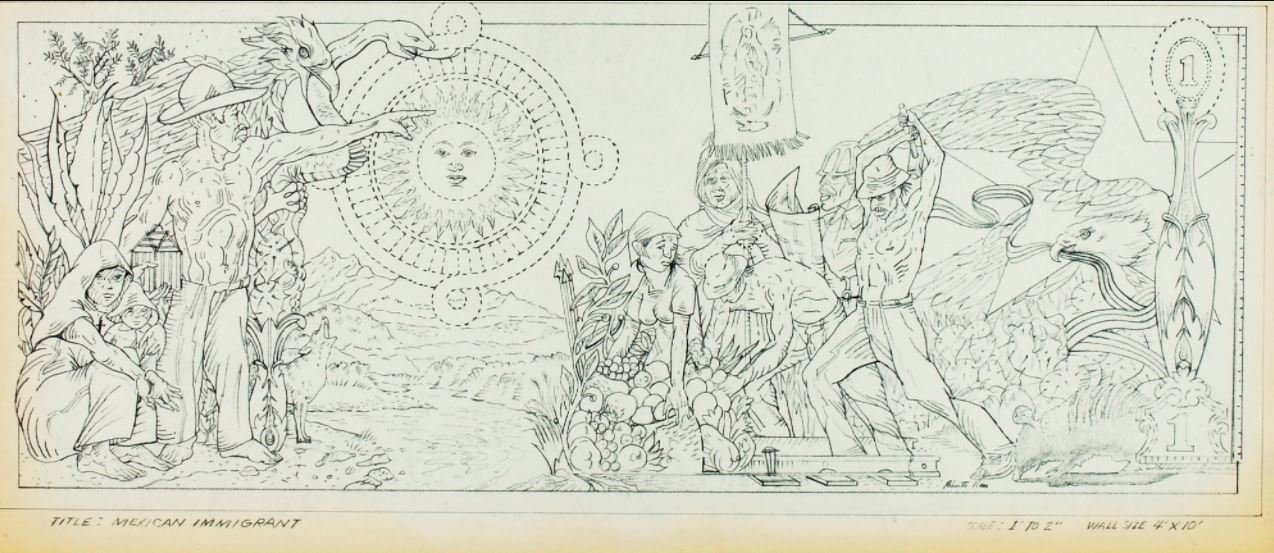

Mexican Immigrant, by Roberto Rios. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Visual Art Integration

Extension Activity: Create a Historical Timeline

Find instructions for this optional activity in the teacher's guide.

Learning Checkpoint

- What are some examples of historical events that contributed to the systemic oppression faced by the Mexican American community during the Chicano movement?

End of Path 1! Where will you go next?

Historical Symbols and Musical Sounds

Path 2

25+ minutes

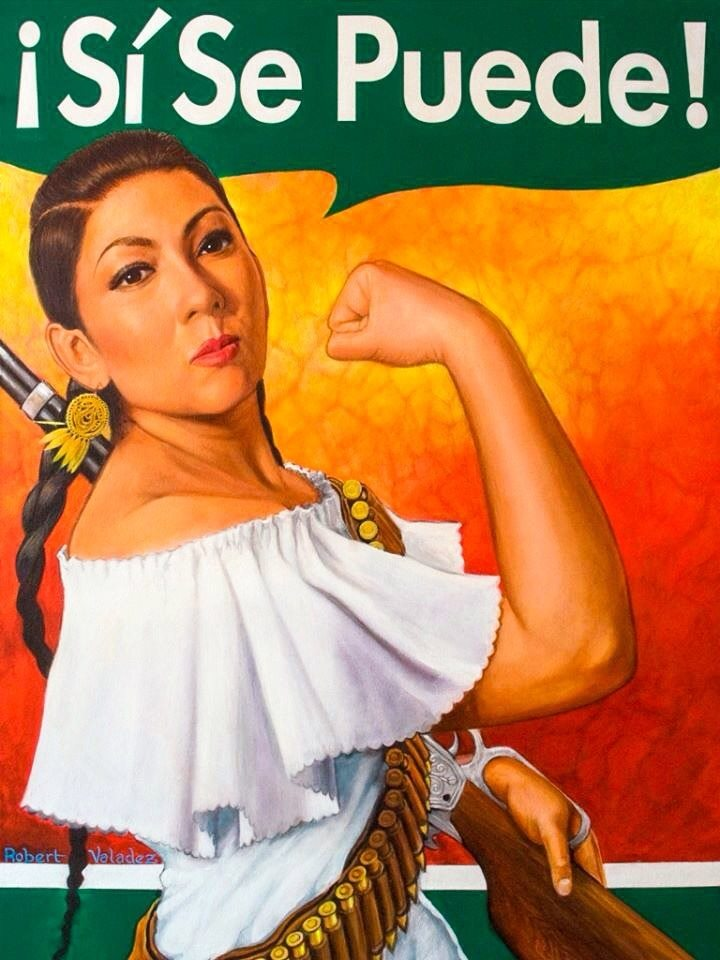

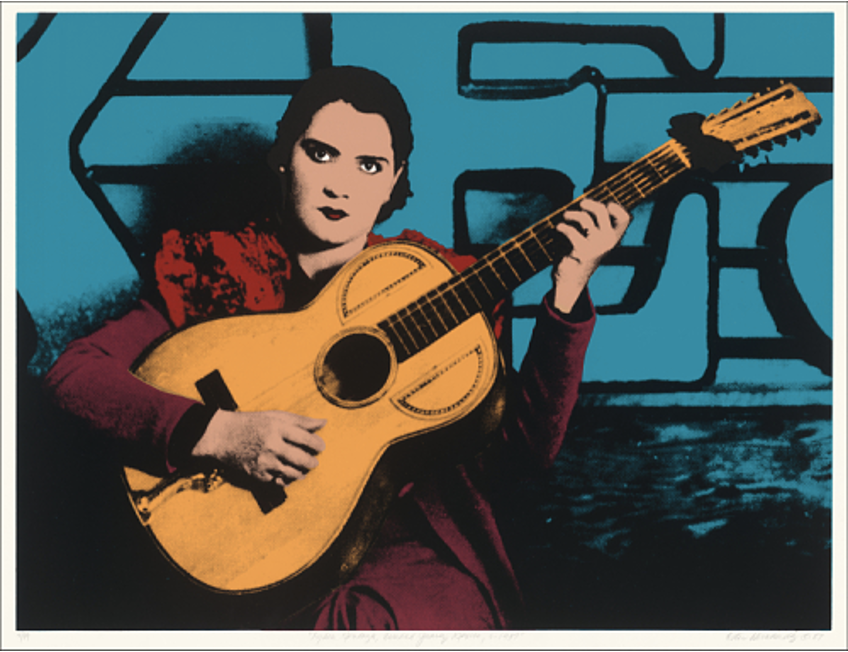

Rosita, by Robert Valadez. Robert Valadez Fine Arts.

Review: Historical Symbols and Music

The song “Corrido de Aztlán,” written by Daniel Valdez during and for the Chicano movement (late 1960s), includes many lyrical references to important historical and cultural events, people, and symbols (e.g., Aztlán, the Mexican Revolution, Pancho Villa, etc.).

Attentive Listening: "Corrido de Aztlán"

Listen to a short excerpt (30-45 seconds) from Suni Paz’s recording of Valdez's "Corrido de Aztlán." Think about this guiding question:

El concepto de Aztlán, by Judith Hernández. UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

Which instrument is playing the steady beat?

The tambourine is playing the steady beat.

Listen again . . . This time, clap or tap along with the tambourine on the steady beat.

Engaged Listening: Tambourine

Tambourine. National Museum of American History.

Attentive Listening: "Corrido de Aztlán"

Listen to this short excerpt again and consider a new guiding question:

What other instruments do you hear?

El concepto de Aztlán, by Judith Hernández. UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

What Instruments Did You Hear?

This recording features a variety of interesting instruments, such as:

- Guitar

- Güiro

- Bongos

- Bombo Drum

From Left to Right: Güiro, Puyero de güiro (Güiro Pick), LP Bongos. National

Museum of American History.

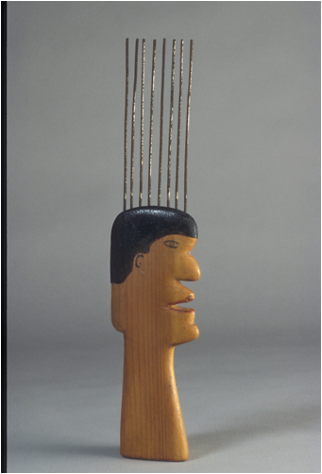

Integrating: The Bombo

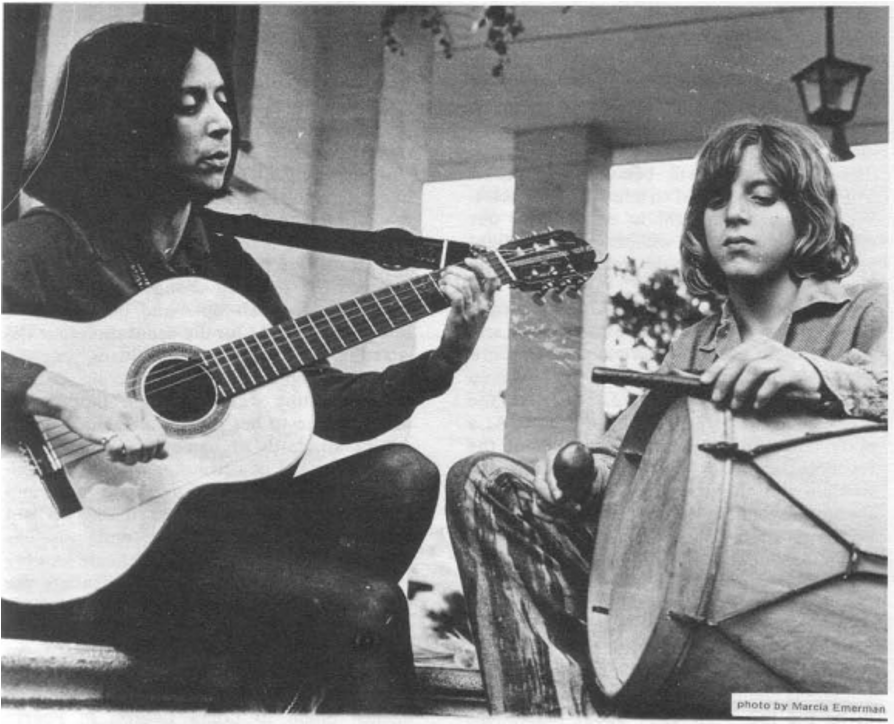

The bombo is a bass drum from Argentina and Chile.

Suni Paz (Guitar) and Ramiro Fernández (Bombo Drum), photo by Marcia Emerman. Paredon Records.

It has two cowhide drumheads, and its body is made from a hollowed-out tree trunk.

It is struck with a mallet (padded stick) on the drumhead, and a drumstick on the rim, producing two distinct sounds on the same drum.

Extension Activity (Enactive Listening): Make and Play a Drum!

- Using an empty container (e.g., oatmeal, coffee) students can make their own drums.

- Cover the ends of the container with plastic lids, felt, foam, rubber, etc.

- Experiment with making different sounds.

- Listen to the recording again and play along with the sound of the bombo.

Colorful Drum, 151383163 | © Lkeskinen0 |Dreamstime.com.

Attentive and Engaged Listening: "Adelita"

Next, listen to an excerpt from a different (but related) recording:

What instrumental sounds do you hear?

Can you clap along on the steady beat?

Can you tap along with a repeated rhythm?

This live recording features:

- A female voice

- 12-string guitar

-

Audience participation (clapping)

This version of “Adelita,” a well-known Mexican folk song, was recorded by the famous Mexican American singer Lydia Mendoza at 67 years old (1982).

Lydia Mendoza, Ciudad Juarez, 1937, by Ester Hernández. National Portrait Gallery.

"Adelita" Instrumentation

Attentive Listening: "Adelita"

What are two words would you use to describe Lydia Mendoza's voice on this recording?

Listen to the same short excerpt at least two more times, and think about new guiding questions.

What do you think this song is about (what/who is an "Adelita")?

Integrating: What is an Adelita?

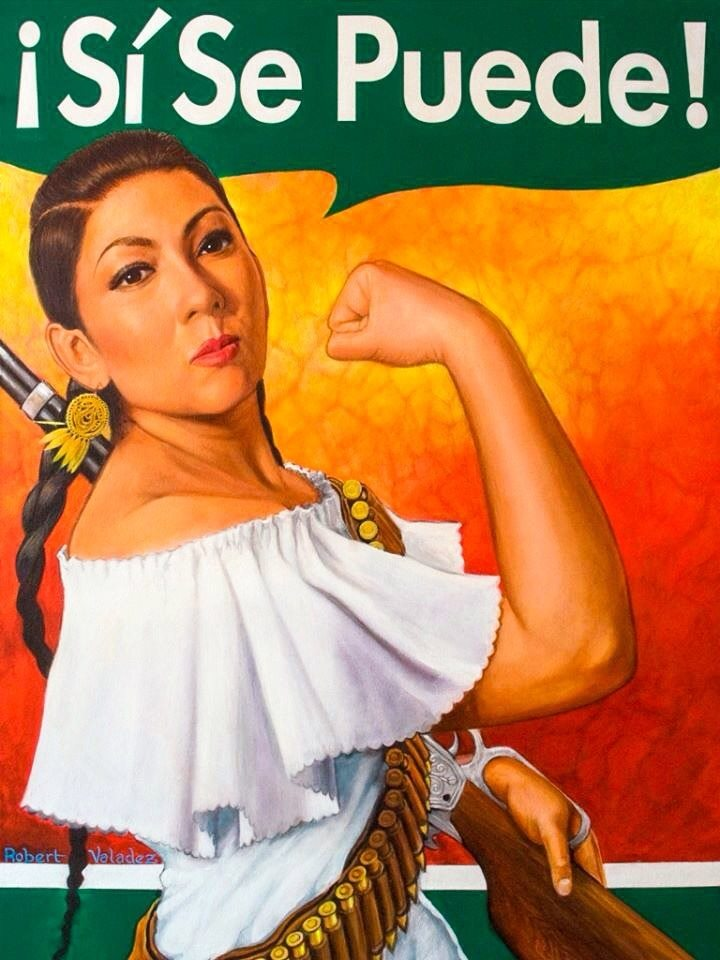

Although this well-known song was originally written about one particular female soldier (soldadera) during the Mexican Revolution, over time, the name Adelita has been used to describe women "warriors": women who are willing to fight for their rights.

Adelita, by Al Rendón. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Integrating: La Adelita

“La Adelita” has become an inspirational symbol of female empowerment and action . . . an Adelita is a heroine of sorts.

During the Chicano movement, activists invoked the historically powerful image of La Adelita, as they fought for social change and women’s rights.

About the Performer: Lydia Mendoza

Lydia Mendoza herself can be viewed as an “Adelita”: She made her voice heard.

Lydia Mendoza - First Queen of Tejano Music. Cover art by Beth Weil. Arhoolie Records.

Lydia Mendoza was a solo female artist who sang exclusively in Spanish.

She possessed a clear, powerful voice and accompanied herself on a 12-string guitar.

Throughout her over 70-year career, she recorded over 100 songs, and gave over 1000 live performances.

Extension Activity: Research Women Warriors!

- In what other cultures, times, and places can we see examples of women warriors?

- Find an example of an “Adelita” in another context.

- Share what you discover with the class!

- Find an example of a song about a strong woman from any culture, time, or place. Compare the song with the song "Adelita."

Learning Checkpoint

- What types of historical symbols did musicians reference during the time of the Chicano movement?

- What instrumental timbres did Suni Paz and Lydia Mendoza use in their recordings of "Corrido de Aztlan" and "La Adelita"?

End of Path 2: Where will you go next?

Music and the Mexican American Generation

Path 3

45+ minutes

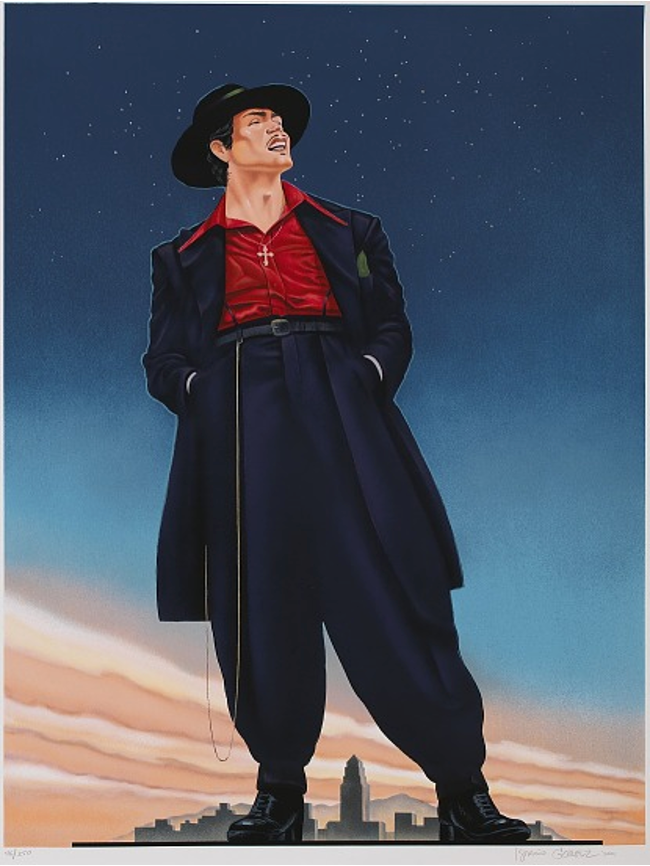

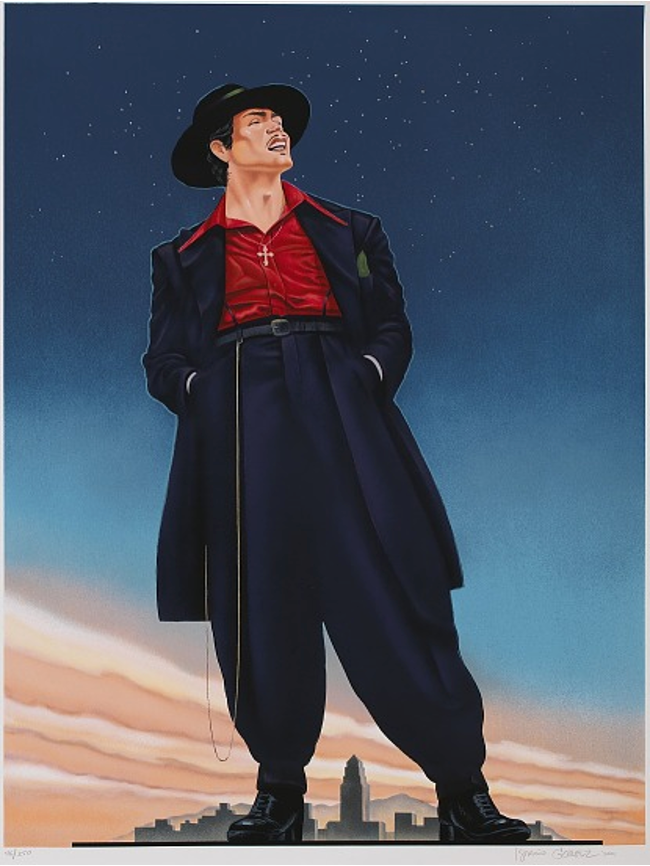

Zoot Suit, by Ignacio Gomez. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Mexican Americanism

In the early part of the twentieth century, people in the Mexican American community maintained a deep connection to the Mexican part of their identities.

Many Mexican immigrants and workers viewed the United States as a temporary place of residence and longed for the day that they would be able to return to their true “home” (Mexico).

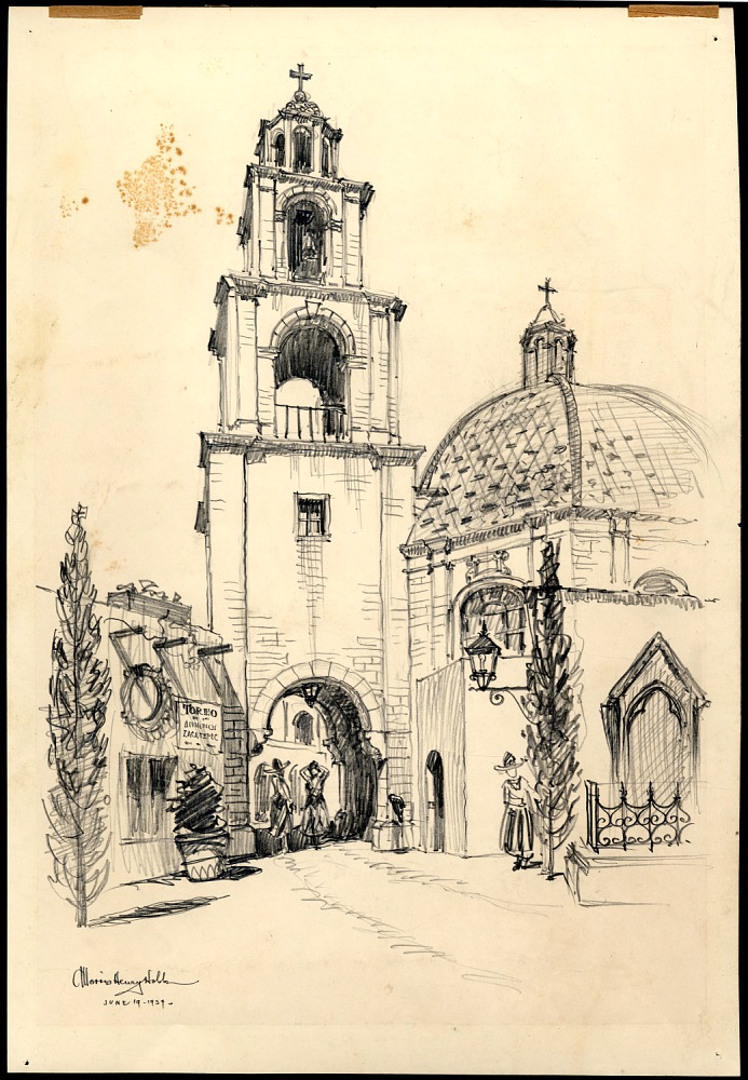

Old Mexico, by Morris Henry Hobbs. National Museum of American History.

Shifting Identities

The 1940s marked a distinct identity shift within the Mexican American community.

People began to embrace the United States as their permanent home but felt “stuck” in between two cultures: They were neither fully Mexican nor American.

Cultural Assimilation

During the 1940s and 1950s, a rising number of Mexican Americans wanted to assimilate more fully into American culture.

Cultural assimilation is the process by which a person or group’s culture comes to resemble that of another group (usually the dominant group).

The Mortar of Assimilation, by C. J. Taylor. National Museum of American History.

Some Examples of Assimilation During this Time

- Speaking English only

- Wanting to be classified as white only

- Demonstrating “loyal citizenship” and “patriotism”

- Faith in the educational system

- Faith in the “American Dream” (achieving middle-class status with hard work)

- Changing/"whitening" one’s name

- Embracing American popular culture (including musical styles like rock and roll)

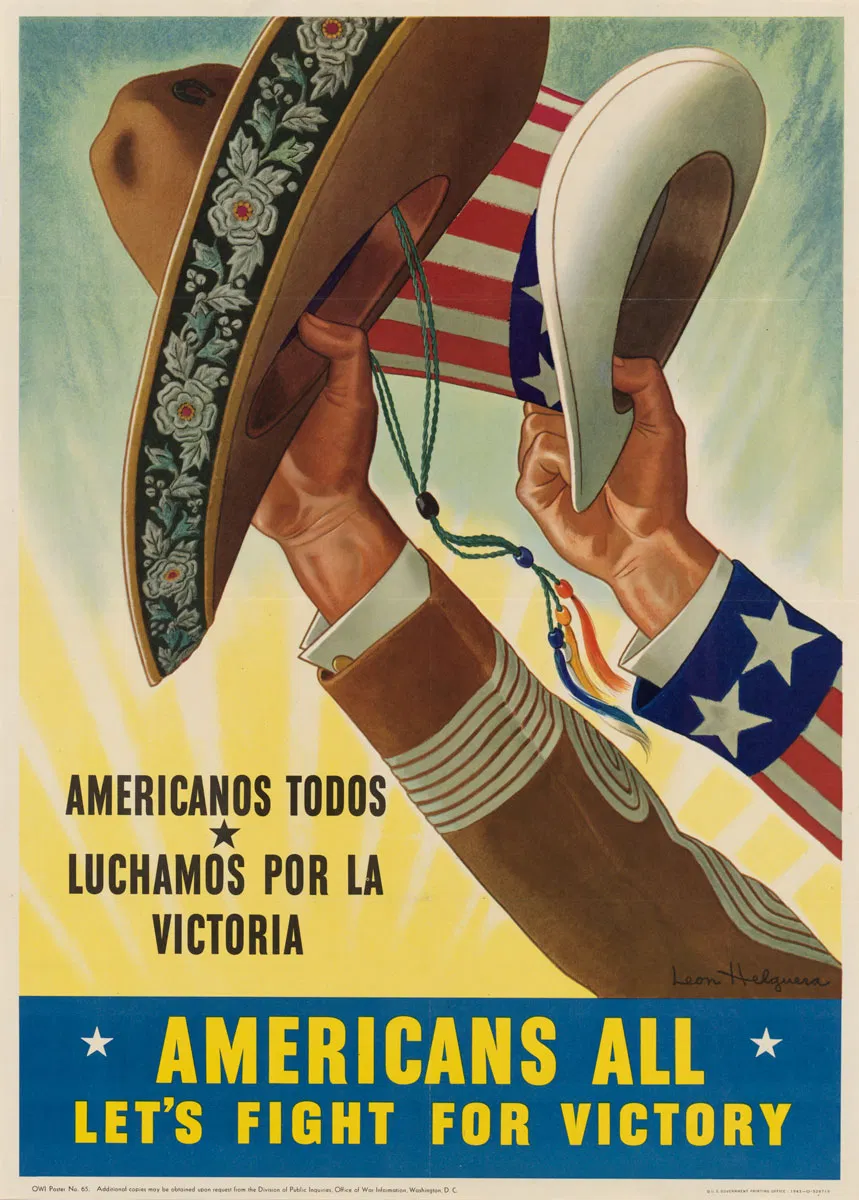

The Mexican American Generation

During the 1940s and 1950s, the prevailing attitude among Mexican Americans was one of hope.

Although there were pockets of resistance to the idea of assimilation, many Mexican Americans believed that “if they just tried hard enough, American society would embrace them” (Montoya, 2016, p. 50).

People who were born and lived during this time are often referred to as the “Mexican American Generation.”

Americans All: Let's Fight for Victory, by Leon Helguera. National Archives.

Artist Spotlight: Ritchie Valens

Ritchie Valens (born Richard Steven Valenzuela), lived during the 1940s and 1950s and experienced some of the pressure to assimilate that was common in the Mexican American community during this time.

Ritchie Valens, widely regarded as the first Mexican American rock and roll star, died in a plane crash at the young age of 17.

Pacoima Mural Memorial, by Levi Ponce. Photo by Circe Denyer. PD, via PublicDomainPictures.net.

- Born in California in 1941 to Mexican immigrant parents

- Spoke very little Spanish at home

- Learned to play the guitar at age 11

- Played a wide variety of styles…from Mexican folk to rock and r&b

- Like many Mexican Americans, he experienced racial discrimination during childhood and adolescence

- At his agent’s urging, he Americanized his name to be more marketable

- His death (along with Buddy Holly and the Big Bopper) was memorialized by Don McLean in the song “American Pie”

Spotlight: Ritchie Valens (continued)

Ritchie Valens: Optional Extension Activities

"La bamba"

One of Ritchie Valens’s most famous songs, “La bamba,” was originally a son jarocho song (a popular regional style from Veracruz, Mexico).

This song has an associated dance and is often played/performed at weddings and other special events.

"La bamba" (and other sones jarochos) is commonly played using arpa jarocha (harp) and jarana and requinto jarocho (guitar-like instruments).

Arpa jarocha, jarana jarocha, and requinto jarocho, photo by Daniel Sheehy. Musicians pictured are José Gutiérrez and Los Hermanos Ochoa. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Attentive Listening Activity: "La bamba"

In the next activity, you will identify similarities and differences between a more traditional interpretation of “La bamba” and the version made famous by Ritchie Valens.

- Pay attention to the ways in which the performers apply music elements and expressive qualities.

- Consider using the provided “Attentive Listening” worksheet to keep track of your observations.

"La bamba" (Traditional Version)

First, listen to a traditional version of “La bamba,” as played by José Gutiérrez and Los Hermanos Ochoa (musicians from Veracruz, Mexico).

"La bamba" (Ritchie Valens's Version)

Next, listen to a short example from Ritchie Valens’s version of “La bamba.”

Again, you can keep track of your thoughts and observations on your listening template.

Optional: Compare and Contrast

If time allows, compare these two versions of “La bamba.”

Were there similarities and/or differences in:

- Tempo?

- Melody?

- Rhythm?

- Instrumentation?

- Style?

- Mood?

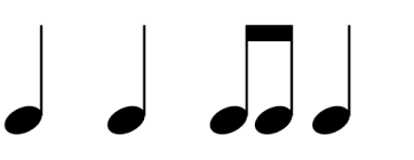

"La bamba" Play Along: Clap a Rhythm

Next, you will have an opportunity to perform "La bamba" in several different ways (along with Ritchie Valens’s version of the song)!

First, clap along with the bell pattern:

"La bamba" Play Along: Strum Chords

"La bamba" only has three chords (C, F, G), and the progression repeats for the duration of the song . . . which makes it a great play-along song for students who are learning to play a chordal instrument like guitar, ukulele, or piano.

After reviewing the chords listed above, play Ritchie Valens's version of "La bamba" again. If students are ready, they can strum along.

"La bamba" Play Along: Sing

Play Ritchie Valens's version of "La bamba" again.

This time, try to sing along.

"La bamba" Play Along: Learn a Riff

- This suggestion will work best for students who play (or are learning to play) a chordal instrument such as guitar, ukulele, or piano.

Ritchie Valens’s version of this song has a short, recognizable riff, a guitar pattern that repeats throughout the song.

Students can find an online tutorial (there are many) and learn to play it!

Perform "La bamba"!

Customize your own arrangement based on the interests and skills of students in the class.

Suggestions: Students can sing, play the bell pattern, keep a steady beat on another rhythm instrument, play a simple rock beat on the drum set, play the repeated melodic riff on a guitar, electric bass, or ukulele, play chords on the piano, guitar, or ukulele, or trade improvised solos.

Ritchie Valens' Rise to Fame

Ritchie Valens’s quick rise to fame was inspiring, but in many ways, it was an anomaly.

Unfortunately, attempts to fully assimilate into American mainstream society during the 1940s and 1950s were often unsuccessful.

Despite demonstrating strong work ethic, good citizenship, loyalty, and patriotism, members of the Mexican American community continued to face obstacles related to discrimination and exploitation.

Lonestar Restaurant Association Sign, ca. 1940s, photo by Adam Jones, PhD. Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0).

Learning Checkpoint

- Why did many Mexican Americans want to assimilate more fully into American culture during the 1940s and 1950s?

- Were most assimilation attempts during this time successful? Why or why not?

- What are some similarities and differences between a traditional version of “La bamba” and Ritchie Valens’s interpretation?

End of Path 3 and Lesson Hub 2: Where will you go next?

Lesson Hub 2 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of:

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Rhino Records

Images courtesy of:

Archives of American Art

The Arhoolie Foundation

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

National Archives

National Museum of American History

National Portrait Gallery

National Postal Museum

Library of Congress

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Robert Valadez Fine Arts

UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

TM/© 2021 the Cesar Chavez Foundation. www.chavezfoundation.org

Lesson plan materials courtesy of:

TeachRock.org

© 2021 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information

This Lesson was funded in part by the Smithsonian Youth Access Grants Program with support from the Society for Ethnomusicology and the National Association for Music Education.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 2 landing page.