Listen What I Gotta Say: Women in the Blues

Lesson Hub 2

Before the Blues: From Africa to the United States

6th grade–8th grade

What West African influences can you hear in blues music?

Field Workers, by Ellis Wilson. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The question to consider throughout this Lesson is:

Before the Blues: From Africa to the United States

Blues, by Robert Cottingham. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

West African Connections to the Blues

Path 1

30 minutes

The Music Maker - Mood V, by Solomon Irein Wangboje. Smithsonian National Museum of African Art

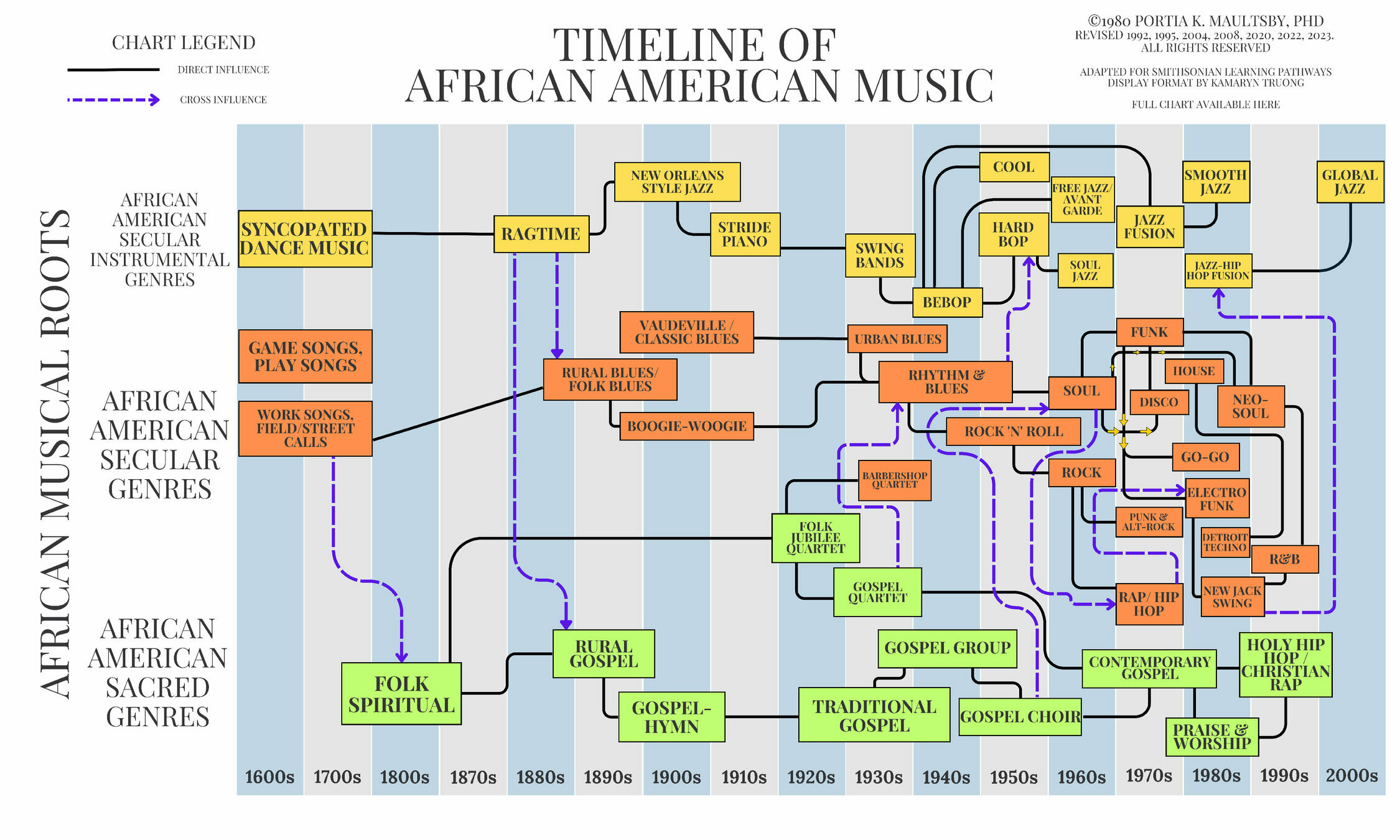

Tracing the Origins of the Blues

Much like other music styles, the blues developed from many factors (time, people, location, and need).

"Session Blues," by Big Mama Thornton.

It is impossible to trace the exact roots of the musical style that became known as the blues.

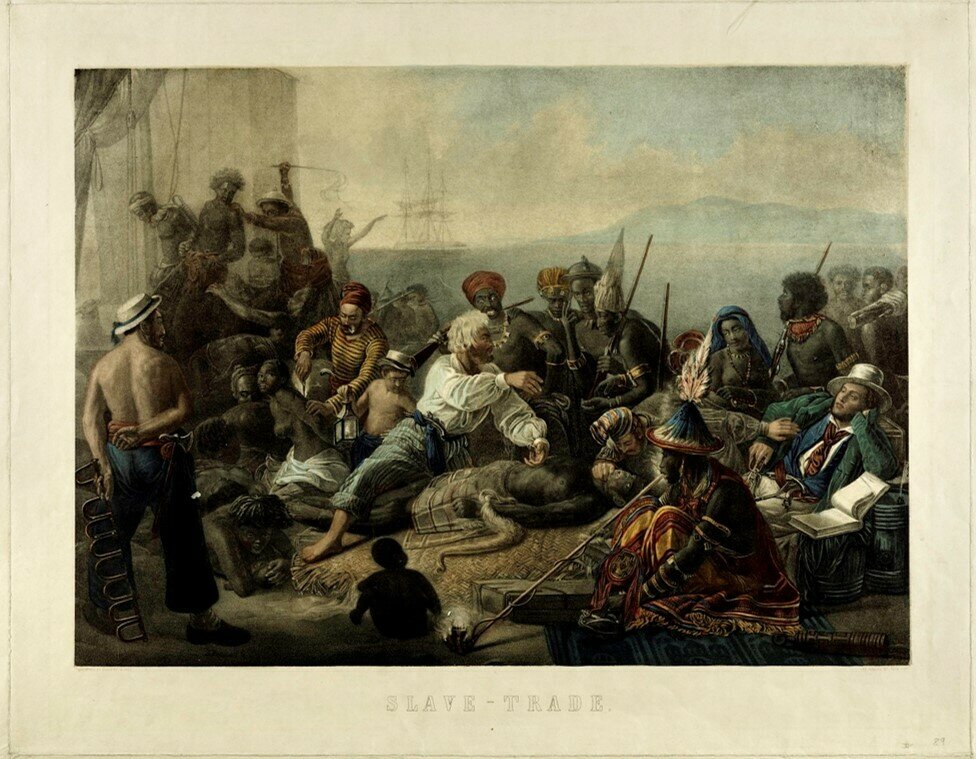

Historical Context: Transatlantic Slave Trade

-

Over 300 years ago, millions of people from Africa were forcefully enslaved and brought to the Americas to develop the “New World.”

-

Though forced from their lands and families, these enslaved peoples maintained aspects of their culture.

Slave-Trade, by Currier & Ives. National Museum of American History.

People

But ... the blues itself was not born in Africa, nor the moment when the first Africans set foot on American soil in 1619.

The blues was developed by people of African descent as they merged their music traditions with those learned in the Americas.

Time

-

The blues, like other music genres, developed over time.

-

Between the 17th and 19th centuries, new sounds formed from many different music styles, including Field hollers/Work songs, Ring Shouts, and Spirituals.

-

The merging of these sounds eventually developed into what we now know as the blues.

Click to the next slide to analyze a timeline that shows the evolution of African American music.

Jump to discussion at end of Path (Slide 21)

Location

The blues was created in the American South.

Until the 20th Century, the bulk of African Americans lived in the American South, in states such as...

State Drawings, by Danielle Nalangan.

South Carolina

Georgia

Texas

Mississippi

North Carolina

Alabama

Louisiana

Need: Post-Emancipation

Blues music began to emerge during this time, as a way for people to express their feelings about these circumstances.

After the end of the Civil War (1865), slavery was legally abolished and African Americans freed themselves.

But many African Americans were still restricted from voting, getting an education, moving freely, and working certain jobs.

Some African Americans were forced to continue working on farms for little or no money.

Combining Influences: Becoming the Blues

-

As people created and played music to express their feelings, they pulled from familiar musical characteristics that existed around them (local, African, and European).

But, through listening, we can guess where some characteristics of blues came from . . .

- Because this process happened over centuries, it is impossible to identify exactly which musical practices were of African roots, local, or of European influence.

Listening for Blues Characteristics

Listen for these common musical characteristics in blues music . . .

Where do you think these characteristics originated?

1

2

3

4

Polyrhythm

“Session Blues” - Big Mama Thornton

Call and Response

“Session Blues” - Big Mama Thornton

Narrative Storytelling

“A Good Man Is Hard to Find” - Bessie Smith

Guitar Picking Style

“Steamboat Whistle” - John Jackson

Generally Speaking .....

West African Connections

Musical characteristics like narrative storytelling, call and response, polyrhythms, and certain guitar picking styles were influenced by music practices found in West Africa.

Africa Regions Map, West Africa, by Peter Fitzgerald, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Generally Speaking .....

Listening Activity

Within this activity, you will listen to examples of music traditions from several regions in West Africa.

As you listen, try to identify the musical characteristic represented:

- Call and response

- Polyrhythms

- Narrative storytelling

- Picking styles

Once you figure it out, fill in the blank.

Click to the next slide to get started!

Generally Speaking .....

West African Connections: Example 1

Wolof Naming Ceremony, photograph by David Ames. Folkways Records.

Generally Speaking .....

Call and Response

The Wolof (an ethnic group in current day Senegal and Gambia, West Africa) song Ndei Kumba (“Mother Petticoat”) shows the musical practice of CALL AND RESPONSE. The young women singers respond to the lead singer.

Generally Speaking .....

West African Connections: Example 2

Doalga Drum in Village of Nanton, Photograph by Verna Gillis. Folkways Records.

Generally Speaking .....

Polyrhythm

The Dagomba people (an ethnic group in current-day northern Ghana) use three hourglass pressure drums (lunga) to perform their annual “Harvest Songs.” The relationship between the drums creates a POLYRHYTHM.

Generally Speaking .....

West African Connections: Example 3

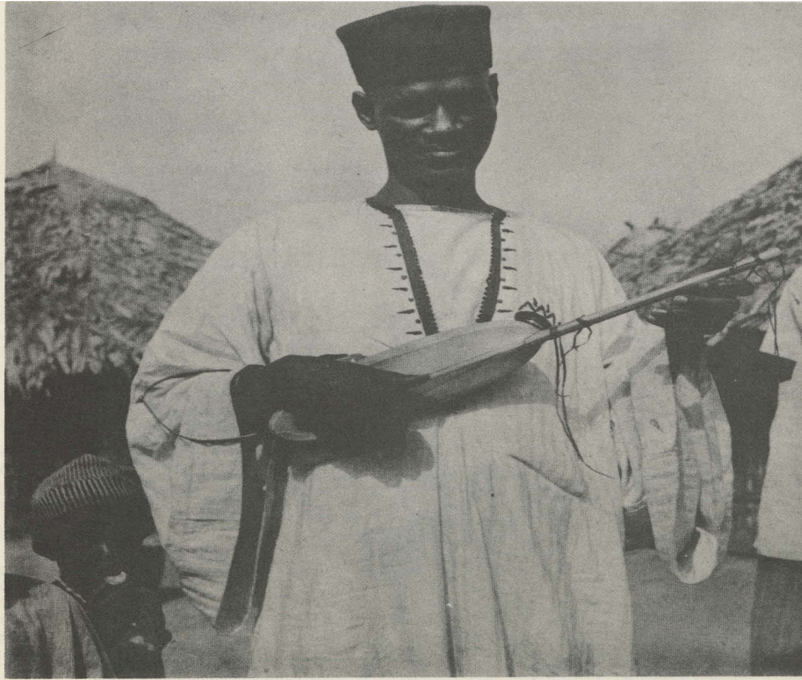

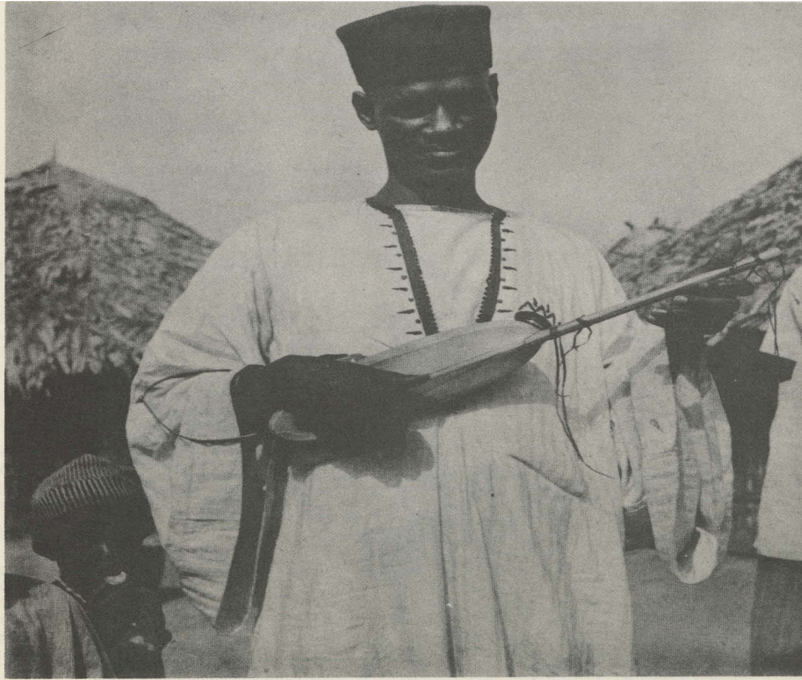

Musician Playing a Musical Bow, unknown photographer. Folkways Records.

Generally Speaking .....

Narrative Storytelling

Generally Speaking .....

West African Connections: Example 4

Gewel Playing Halam, photograph by David Ames. Folkways Records.

Generally Speaking .....

Picking Style

Listening for Blues Characteristics, Take 2

Listen again to these blues songs.

Can you hear the West African elements we just learned about?

Polyrhythm

“Session Blues” - Big Mama Thornton

Call and Response

“Session Blues” - Big Mama Thornton

Narrative Storytelling

“A Good Man Is Hard to Find” - Bessie Smith

Style of Playing

“Steamboat Whistle” - John Jackson

1

2

3

4

Discussion

As you learned in Lesson 1, the blues has influenced many other American popular music styles.

Do you hear any of the West African musical characteristics we identified today in any other popular music styles?

- Call and response

- Polyrhythms

- Narrative storytelling

- Picking styles

Go back to blues timeline to review (Slide 9)

Learning Checkpoint

- Where, when, and why did the blues develop?

- What are some of the musical practices found in the blues that can be traced back to West African music traditions?

End of Path 1: Where will you go next?

Before the Blues: Ring Shouts

Path 2

30 minutes

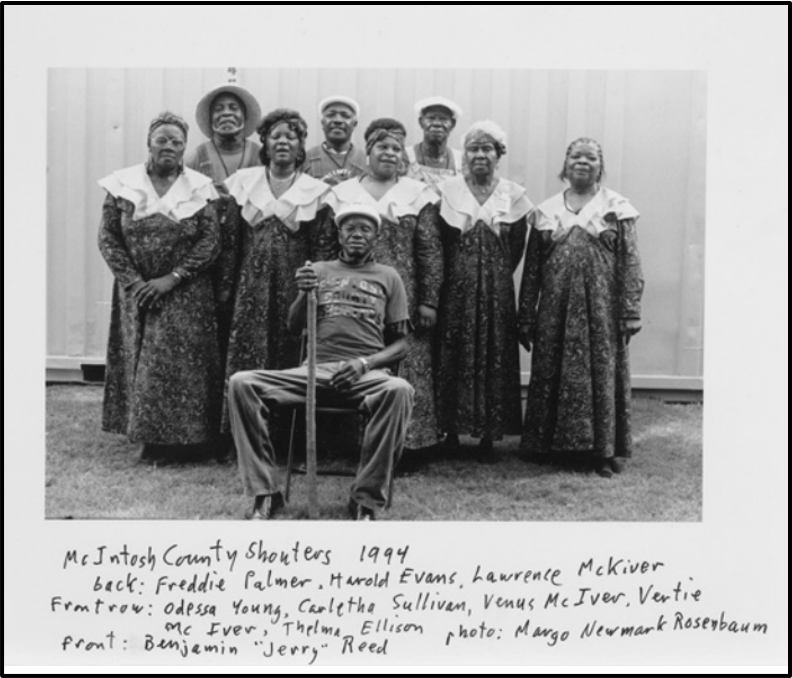

McIntosh County Shouters 1994, photograph by Margo Newmark Rosenbaum. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Watch this video...

...about a group called the McIntosh County Shouters.

McIntosh County Shouters - 'Spirituals and Shout Songs' [Behind the Scenes Documentary],

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Discussion

Based on the information provided in the video, what is a “ring shout?”

About Ring Shouts

The shout is one of the oldest African American performance traditions still alive in North America.

This tradition, first noticed by outsiders in 1845, was found in the coastal areas of South Carolina and Georgia.

This mix of call-and-response singing, percussive rhythm, and expressive dance-like movement, which brings the group together and supports Christian beliefs, has been practiced since slavery in McIntosh County, on the east coast of Georgia.

The term “shout” refers to a worshipper becoming overwhelmed by religious feelings and moving in a joyful, excited way to this emotion.

McIntosh County Shouters

Cover art by Visual Dialogue. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

The group that became the McIntosh County Shouters formed sometime in the early 1900s.

Although the ring shout tradition began to fade away in the 1930s, the McIntosh County Shouters (then known as the Georgia Sea Island Singers) kept it alive.

They began presenting this tradition to the public in 1980.

All current McIntosh County Shouters are descendants of original members and are related to each other by blood or marriage.

West African Influences in Ring Shouts

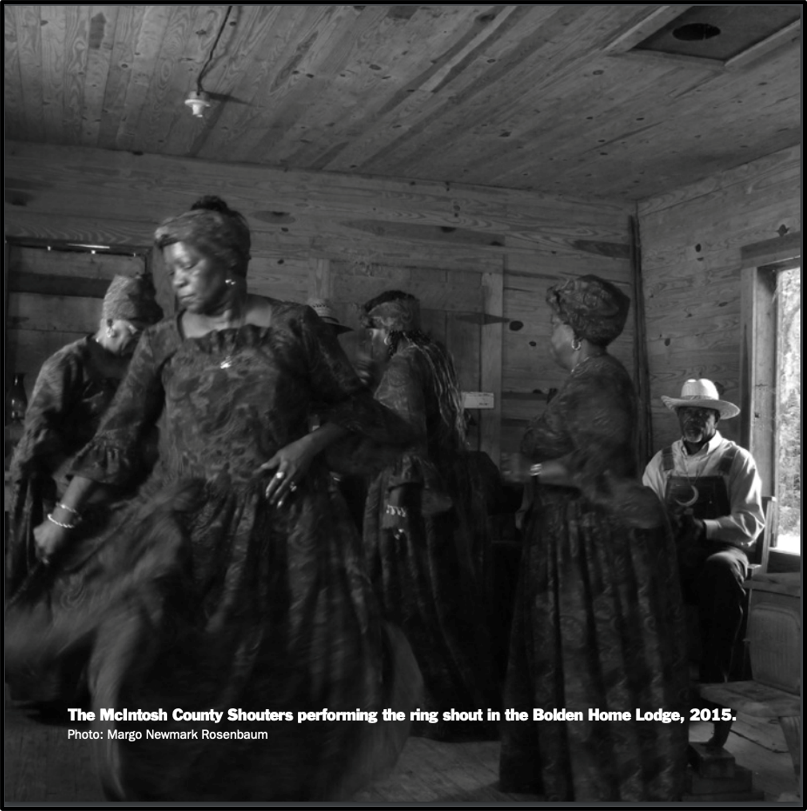

The McIntosh County Shouters performing the ring shout in the Bolden Home Lodge, by Margo Newmark Rosenbaum.

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

The shouts featured in the video we just watched (performed by the McIntosh County Shouters) utilized call and response form and featured a syncopated rhythmic ostinato pattern (played with sticks and hand claps).

The shouts are not a regular part of the church worship service—they take place afterwards, or on other occasions.

Many of the defining elements of ring shouts can be traced back to West African music traditions (repeated syncopated rhythmic patterns, call and response, the importance of ritual and dance)

Watch another video...

...which features the McIntosh County Shouters performing a song called “Jubilee.”

McIntosh County Shouters - 'Jubilee' [Behind the Scenes Documentary], Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Discussion: What did you notice?

After watching the video, reflect on these questions:

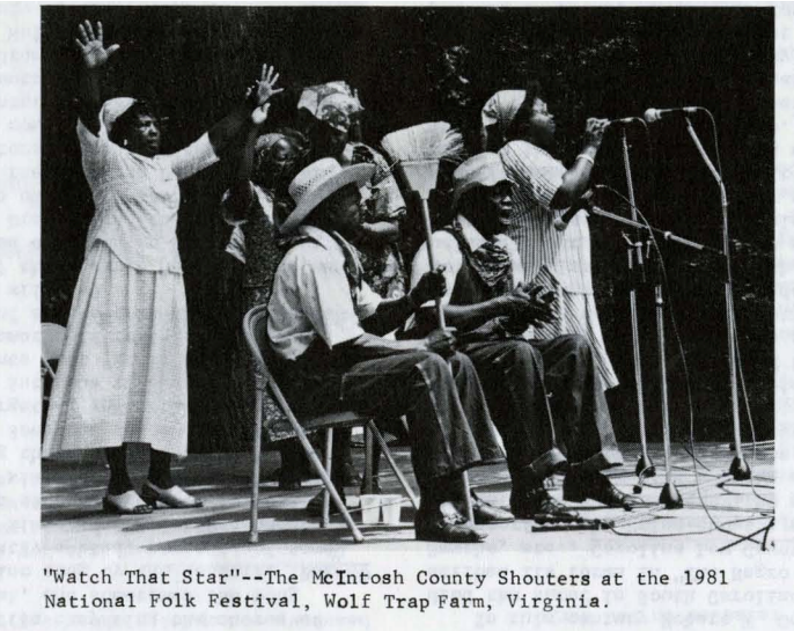

"Watch That Star"--the McIntosh County Shouters at the 1981 National Folk Festival, Wolf Trap Farm, Virginia, by Margo Newmark Rosenbaum. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

What did you notice about movement?

What did you notice about the song structure?

What did you notice about rhythm?

About "Jubilee"

- The performers walked counterclockwise to the beat.

- There was one syncopated rhythmic pattern that repeated for the whole song. It was clapped and tapped with a stick on the ground.

- The song structure itself was very repetitive: one singer called out, and the other singers alternated between two “responses.”

Engaged Listening (Make Music!)

Listen, and learn the repeated rhythmic pattern (hand-clap) by ear.

Clap this pattern along with the audio recording of “Jubilee,” by The McIntosh County Shouters.

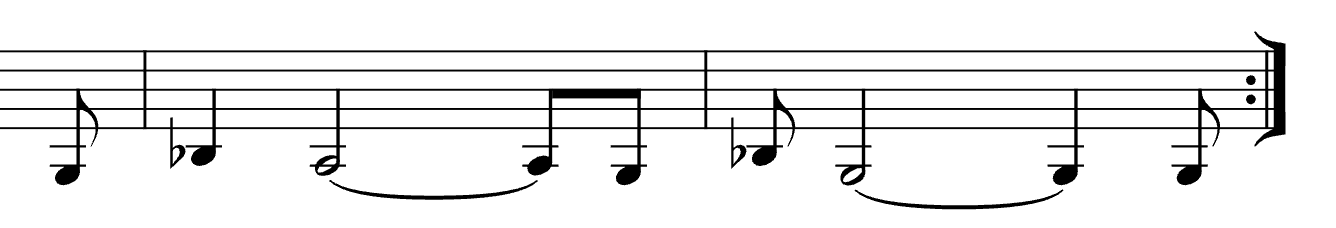

Hand Clap: Rhythmic Analysis

The syncopated rhythmic pattern we just performed is often referred to as 3+3+2.

Most often, the resulting 3+3+2 pattern is notated like this:

4

4

One measure of 4/4 time has 8 subdivisions (eighth notes):

4

4

Within a 3+3+2 pattern, the eighth notes are grouped together like this:

4

4

1 (2) (3) 4 (5) (6) 7 (8)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2

Engaged Listening (Make Music!)

Learn the two main melodic “response” patterns by ear.

- Sing these patterns along with the audio recording:

“Oh, my Lord!”

“I love Jubilee!”

When you are ready, practice singing the response while clapping the rhythmic pattern (along with the recording).

Learning Checkpoint

- What are ring shouts?

- What are some of the musical practices found in ring shouts that can be traced to West African music traditions?

End of Path 2: Where will you go next?

Before the Blues: Field Hollers

Path 3

30 minutes

What is a field holler?

Field Workers (Cotton Pickers), by Thomas Hart Benton. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

Between the 17th–19th centuries, many enslaved Africans were forced to work as plantation laborers in the American South. For fear of rebellion and uprising, they were not permitted to mingle with friends and family on nearby plantations.

Over time, the melodies sung back and forth came to be known as “field hollers.” Field hollers helped maintain a feeling of community among those enslaved.

Men and women working together over a wide stretch of fields maintained social contact throughout the workday by calling back and forth and singing songs together.

Attentive Listening: Field Hollers

Listen to this example of a field holler.

As you listen, think about the following guiding questions:

What do you notice about the structure?

Who do you think is singing?

What do you think the singer is feeling?

What do you notice about the texture?

"Field Call," by Annie Grace Horn Dodson.

Annie Grace Horn Dodson

On this recording of "Field Call," a woman named Annie Grace Horn Dodson recalls (from memory) the call of the field workers during her childhood.

This field call is based on the first three notes of the minor scale (do, re, me), which gives it a melancholy feel.

Annie Grace Horn Dodson, by Harold Courlander. Folkways Records.

More about Field Hollers

Sometimes field hollers were sung in unison (everyone all together), and sometimes the “calls” and “responses” were sung from different parts of the field.

On this recording, you can clearly hear one singer (no harmony or other instruments) and the “call and response” form.

Cotton Pickers, by Merritt Mauzey. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Annie Grace Horn Dodson sings both the “call” and the “response.”

Field Hollers as Communication

In addition to fostering a sense of community, field hollers also served as a form of communication.

Photo of Workers in the Field on Drew Plantation, by Henry Clay Anderson. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Sometimes, the calls included coded messages or a familiar signal.

Field Hollers: Example 2

Listen to another example of a “field holler.”

- As you listen, think about the following guiding question:

What are some similarities and differences between this recording and the previous recording?

"Greeting Call," recorded by Annie Grace Horn Dodson.

This track is entitled “Greeting Call”

-

It was recorded by the same singer . . . Annie Grace Horn Dodson.

-

The mood seems a bit more upbeat.

-

This melody is less repetitive and seems to have some improvisation.

-

Both hollers are secular (no religious meaning).

-

Both hollers utilize call and response form.

About "Greeting Call"

This call has lyrics that tell a story:

A man has returned after a long absence, and is greeted by this question...

(Call): Hey, Rufus! Hey boy! Where in the world you been s0 long? Hey buddy, hey boy!

(Response): Well I been in the jungle! Ain't goin’ there no more!

From the album liner notes:

“The answer is of course metaphoric. It would be understood by the listener to mean that Rufus has been in prison or some other kind of trouble.”

Performance Activity: "Field Hollers"

Within the next activity, you will have a chance to actively engage with the first field holler we listened to today, with and without the recording.

1. Echo Sing

Echo-sing short melodic patterns that include the notes “do, re, me” (the first three notes in a minor scale).

You can echo the patterns using neutral syllables (such as “loo”) or solfège syllables.

2. Echo Sing with Call and Response

Echo-sing the the call and response pattern sung by Annie Grace Horn Dodson in "Field Call" (with the recording):

-

Call: “Who hoo, who hoo”

-

Response: “Yeh hee, yeh hee”

3. Engaged Listening

Listen to the recording again . . .

This time, sing along only with the “responses.”

4. Perform

Split your class into two halves . . .

- Half of the class will sing the “call” while the other half sings the “response.”

- Then . . . feel free to do it without the recording!

- Perform it with a small group of singers or a soloist on the "call"

5. Use Notation

Look at the staff notation for this call and response pattern.

- Sing the pattern while following along with the notation.

-

Discuss: Is it possible to accurately represent this pattern using staff notation? Why or why not?

Extension Activities:

Improvising, Creating, and Documenting

Play with a question/answer activity using the notes “do, re, me”:

- Create a “call” and then rather than echoing, answer back using a different combination of the same three notes.

- Create and notate your own short call and response patterns, using the notes “do, re, me.”

Field Hollers and Blues Connections

Form

-

Many field hollers utilized call and response form.

-

Call and response between the vocalist and instrument(s) is an important part of the blues tradition.

Vocal Style

-

Many field hollers utilized bent pitches

-

Bent pitches or "blue notes" are important to the performance style of the blues.

Improvisation

-

They were often developed without preparation.

-

Improvisation is also an important part of the blues tradition.

Field Hollers after the Civil War

This tradition continued after the Civil War (which ended in 1865), disappearing slowly as the conditions of life changed.

However, when an album of this music was released in 1951, these types of field calls were still heard in many rural parts of the southern United States.

No. 44, Weighing Cotton, photograph by A. W. Möller.

National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Learning Checkpoint

- What are some common features of field hollers?

- What are some of the musical practices found in field hollers that are also found in the blues?

End of Path 3 and Lesson Hub 2: Where will you go next?

Lesson 2 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Sony Music Entertainment

Video courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Images courtesy of

Peter Fitzgerald

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Portia K. Maultsby

National Museum of African Art

National Museum of African American History and Culture

National Museum of American History

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

© 2025 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This Lesson was funded in part by the Grammy Museum Grant and the Smithsonian Youth Access Grants Program, with support from the Society for Ethnomusicology and the National Association for Music Education.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 2 landing page.