Fiesta Aquí, Fiesta Allá: Music of Puerto Rico

Lesson 1

Exploring Puerto Rican Music and Culture

Sea of Flags (Street View), mural by Gamaliel Ramirez, photo by Jason Morris.

The "Sea of Flags" is a street mural created in 2004 by Gamaliel Ramirez. The mural, located in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood, depicts Fiesta Boricua: De Bandera a Bandera, an annual 3-day music and cultural festival held in this Chicago neighborhood. In 2018 the Fiesta Boricua celebrated its 25th anniversary and offered 3 stages for the performance of Puerto Rican salsa, reggaeton, bomba, plena, and more.

Fiesta Aquí, Fiesta Allá

How and why can the idea of fiesta capture the "essence" of Puerto Rican culture and identity?

Lesson Hub 1:

Fiesta Aquí, Fiesta Allá: Exploring Puerto Rican Music and Culture

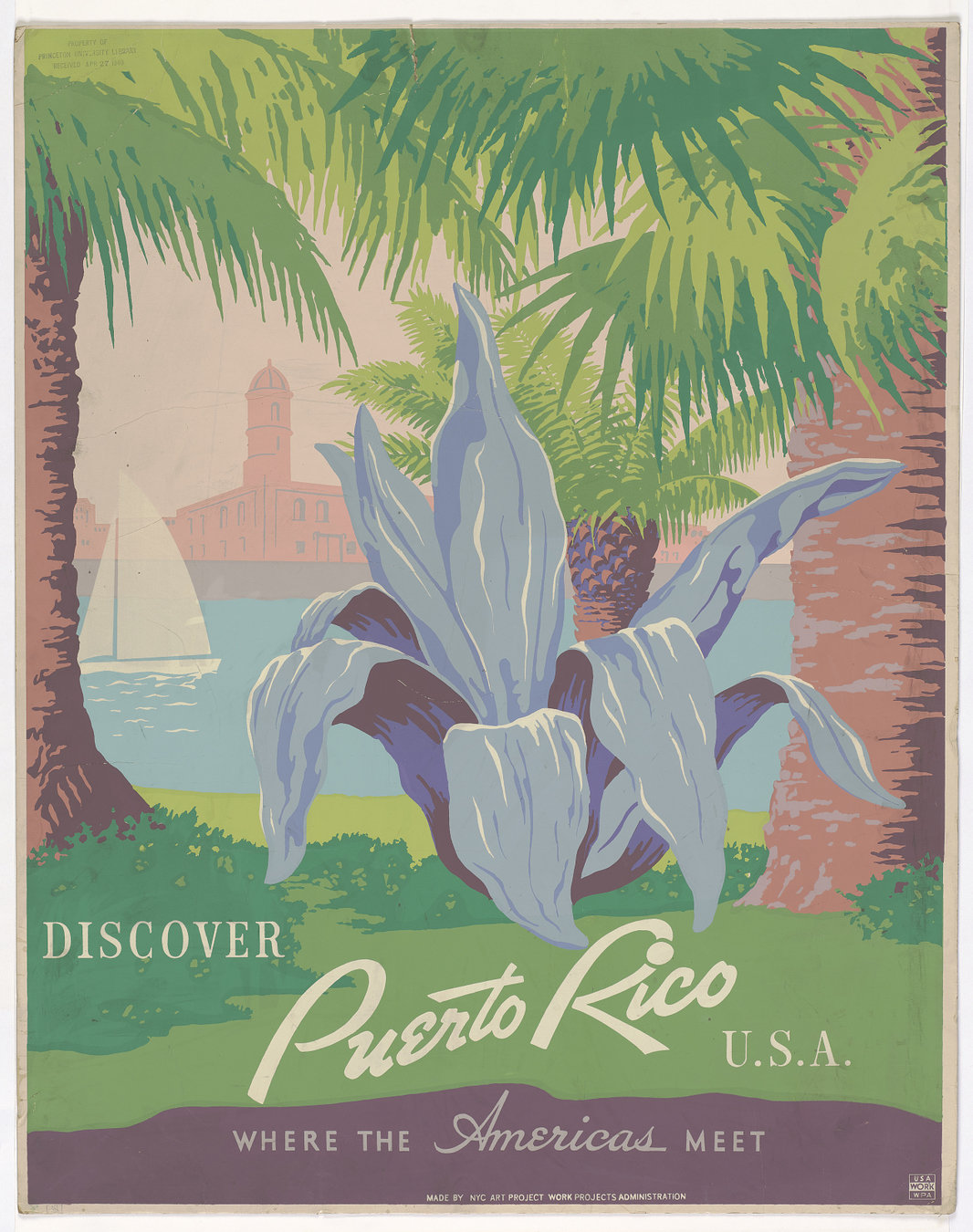

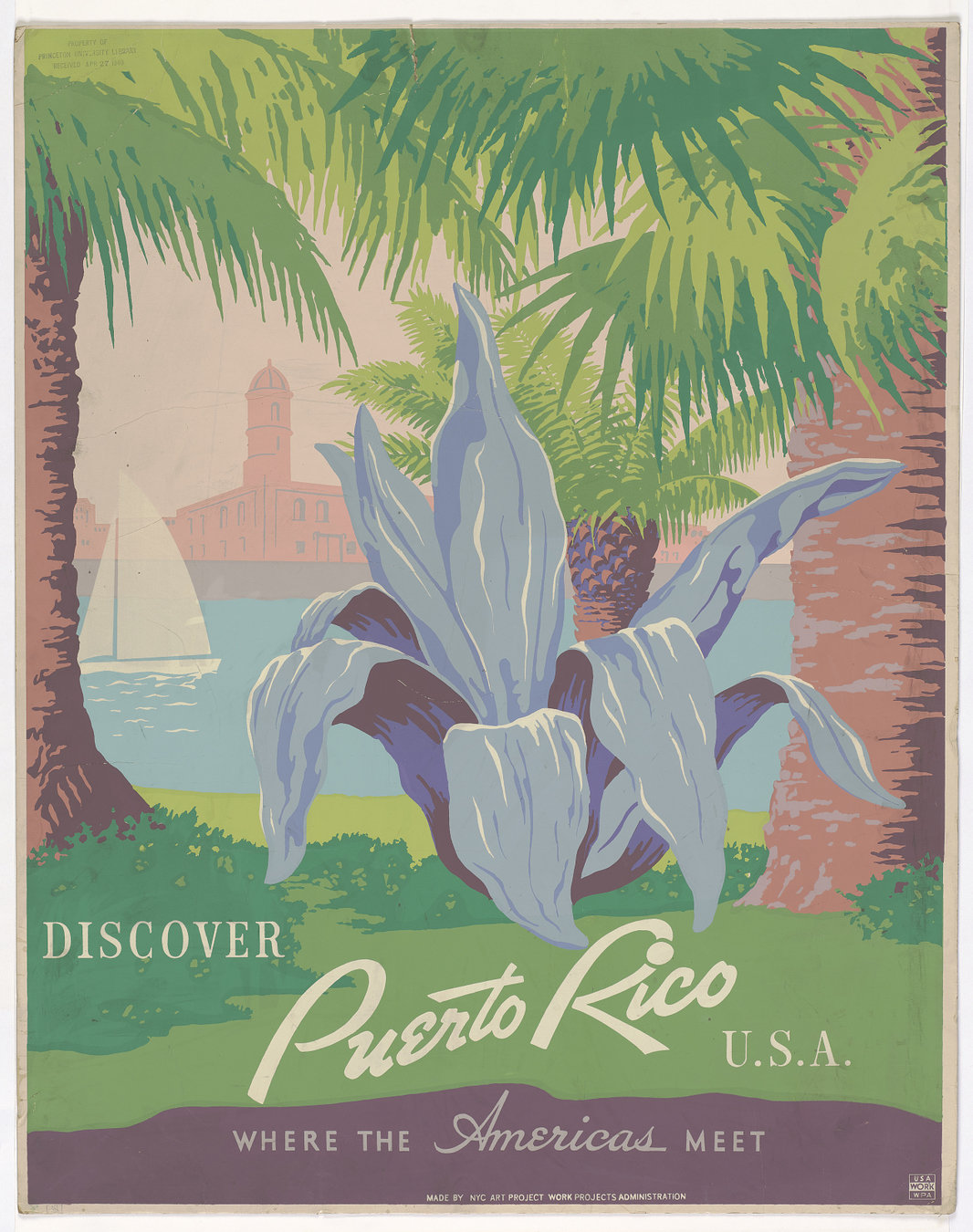

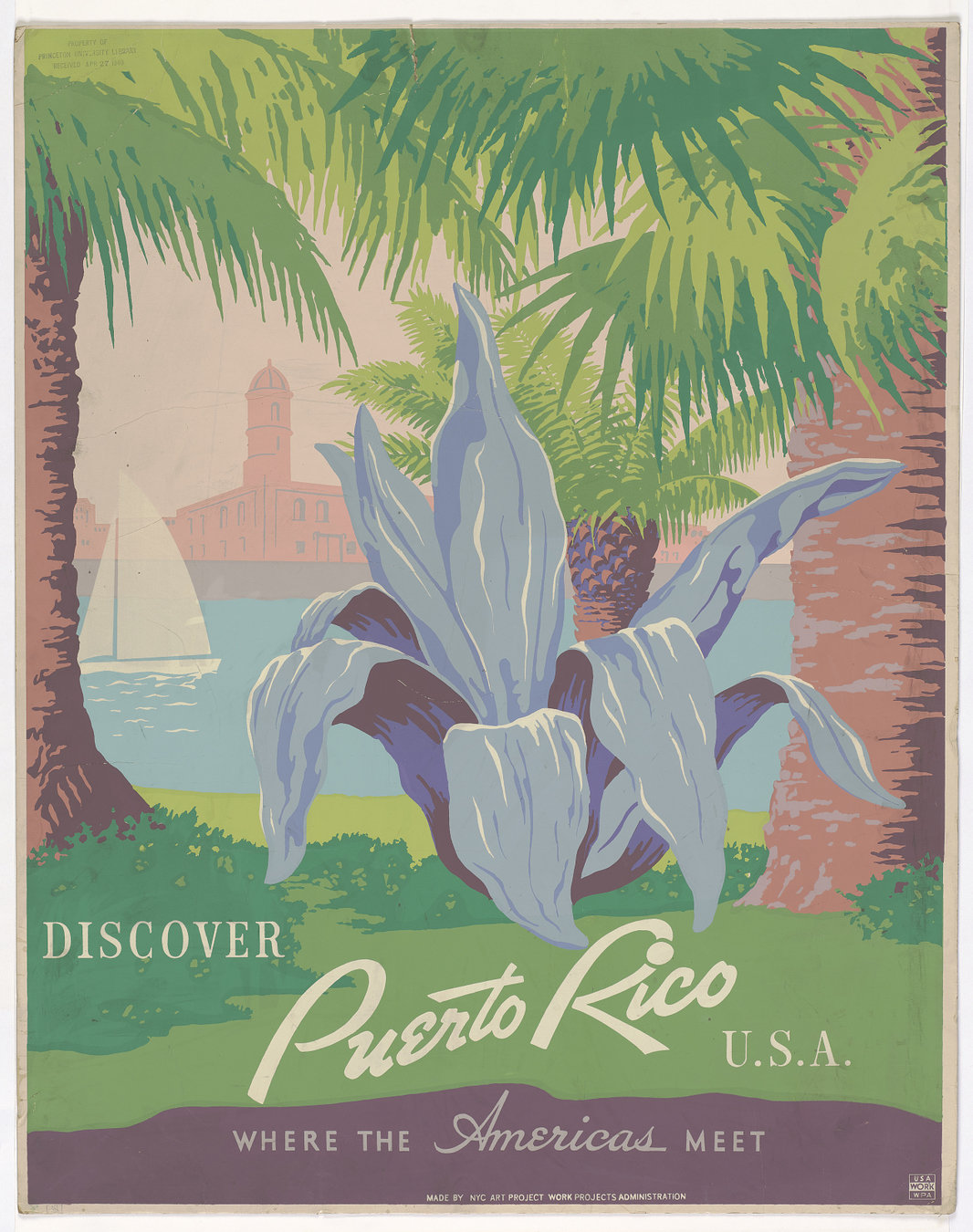

Discover Puerto Rico U.S.A. Where the Americas Meet, by Frank S. Nicholson. Library of Congress.

by Jaíme O. Bofill Calero

Fiesta Aquí, Fiesta Allá: Exploring Puerto Rican Music and Culture

CREATIVE CONNECTIONS

HISTORY & CULTURE

20+ MIN

30+ MIN

30+ MIN

HISTORY & CULTURE

A History of Fiesta in Puerto Rico

Path 1

20+ minutes

Rashelle Burns Dances at the Community Batey in La Perla, Puerto Rico, by Mariana Núñez Lozada. Smithsonian Folklife Magazine.

What Is a Fiesta?

In Puerto Rico, fiestas are social gatherings, often associated with:

-

Catholic religious festivities

-

Secular events

-

Celebrations of life cycles

-

Historic events

Resurrection City: Untitled, Photograph of a Woman Playing a Guitar and Singing, photo by Jill Freedman. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

More About Fiestas

-

Fiestas are celebrated year-round, providing continuity to long-held traditions and encouraging the creation of new ones.

-

Fiestas also represent traditions celebrated in other parts of the Caribbean and Latin America, which highlights Puerto Rico’s historical connection to this region.

Food, Music, Dance, and Fiesta!

In general, fiestas involve three main elements: music, dance, and food.

Some traditional Puerto Rican dishes are made specifically for celebrations.

Mofongo with Shredded Pork and Pork Cracklings, Ramonita's, by Garrett Ziegler. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr.

Mofongo (pictured here) is Puerto Rico's unofficial national dish.

Food, Music, Dance, and Fiesta!

In this video, how do people gather to share food and socialize?

The beginning of this video (which includes the song "El Alma de Puerto Rico," by Ecos de Borinquen) depicts the important relationship between music, dance, and food in Puerto Rican culture.

Ecos de Borinquen - "El Alma de Puerto Rico" [Behind the Scenes Documentary], by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Fiesta in Historical Context: The Taíno

The Taíno – an indigenous people whose ancestors populated the different islands of the Caribbean since 4000 BCE – inhabited Puerto Rico when Columbus arrived in 1493.

- They called the island Borínquen.

- They are likely to have been the first to celebrate "fiestas" on the island.

- Spanish chroniclers called those fiestas areytos.

Columbus Landing on Hispaniola, Dec. 6, 1492; Greeted by Arawak Indians, by Theodor de Bry. Library of Congress.

Fiesta in Historical Context: Areyto

- prepare for war

- commemorate epic tales of battles and other histories

- perform fertility rituals

- hold funerary rites for important members of the community

- perform rituals to recreate religious myths

- serve an essential role in the creation and transmission of collective memory

Areyto Ceremony of the Taíno, unknown artist. {PD US}, via Wikimedia Commons.

Areytos--involving masks, body painting, and theater--were used to ...

Fiesta in Historical Context: The Batey

The term batey is still used in Puerto Rico and the Caribbean to reference a common area or space for social activity.

Children Wait Their Turn to Dance in the Community Batey, photo by Mariana Núñez Lozada. Smithsonian Folklife Magazine.

Areytos took place in the batey:

- A public space at the center of a village

- used for everyday affairs and ritualistic practice

- Ancient batey sites still exist that feature petroglyphs that speak to the religious purpose of the music and dance performed

Fiesta in Historical Context: The Conquista

The Spanish colonization of the Americas was carried out through the military strategy of conquistadores and tactics of evangelization used by friars and monks to convert the native peoples to Christianity.

The image shown here features Saint James the Moor Slayer (Santiago Apóstol), Spain's patron saint and a symbol of the Spanish conquest of the Americas.

Santiago Matamoros, by Pepe, Justina, Jose, and Justina Torres de Ramos. National Museum of American History.

Fiesta in Historical Context: Catholic Fiestas

The presence of the Catholic Church in Puerto Rico introduced Spanish religious customs and traditions. Some examples include:

-

Easter, Christmas, Three Kings Day (Epiphany), Corpus Christi, All Saints’ Day, and patron-saint feast days.

- Each Puerto Rican town dedicates annual fiestas to its patron saint and the Virgin Mary.

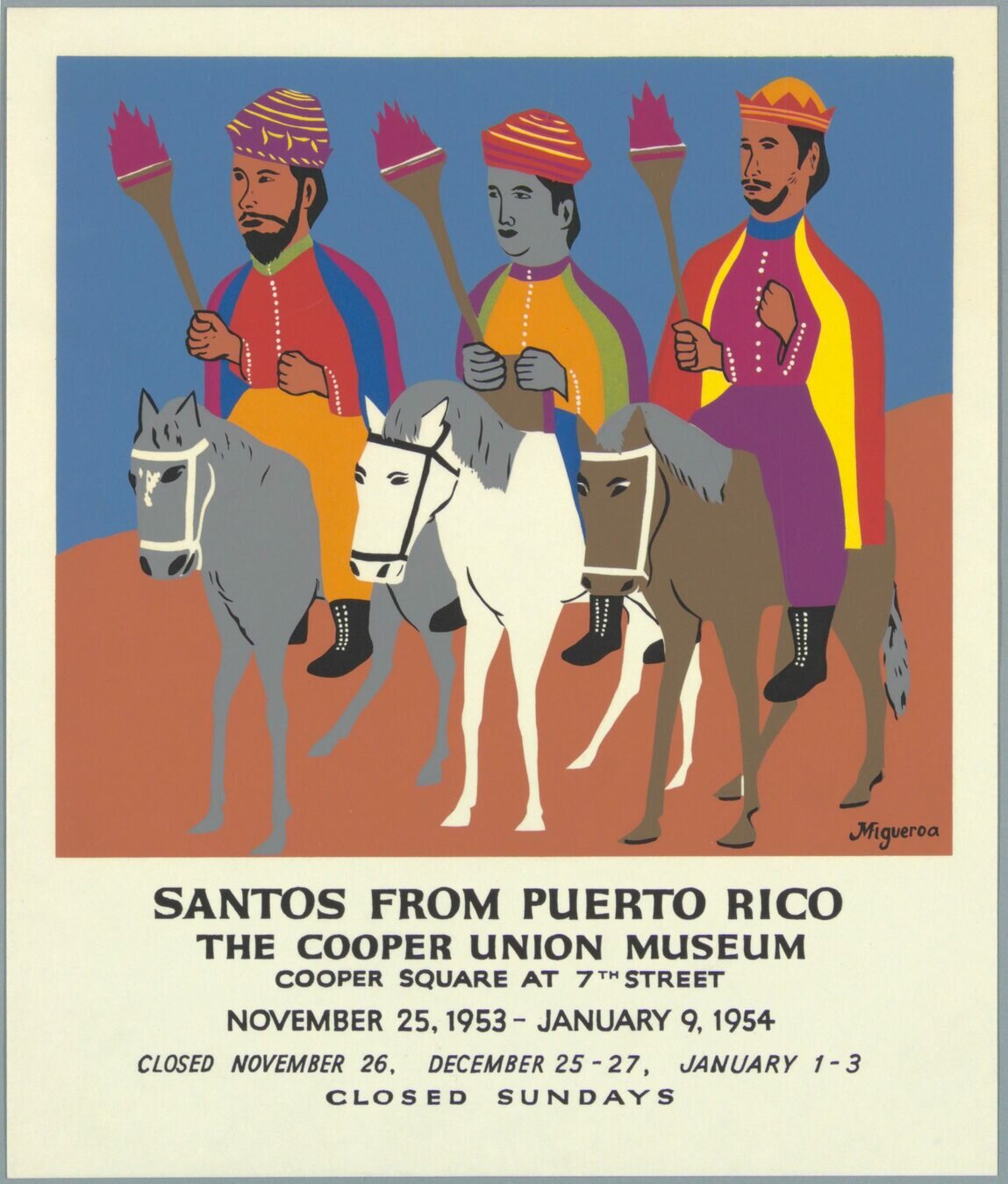

Santos from Puerto Rico, unknown artist. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

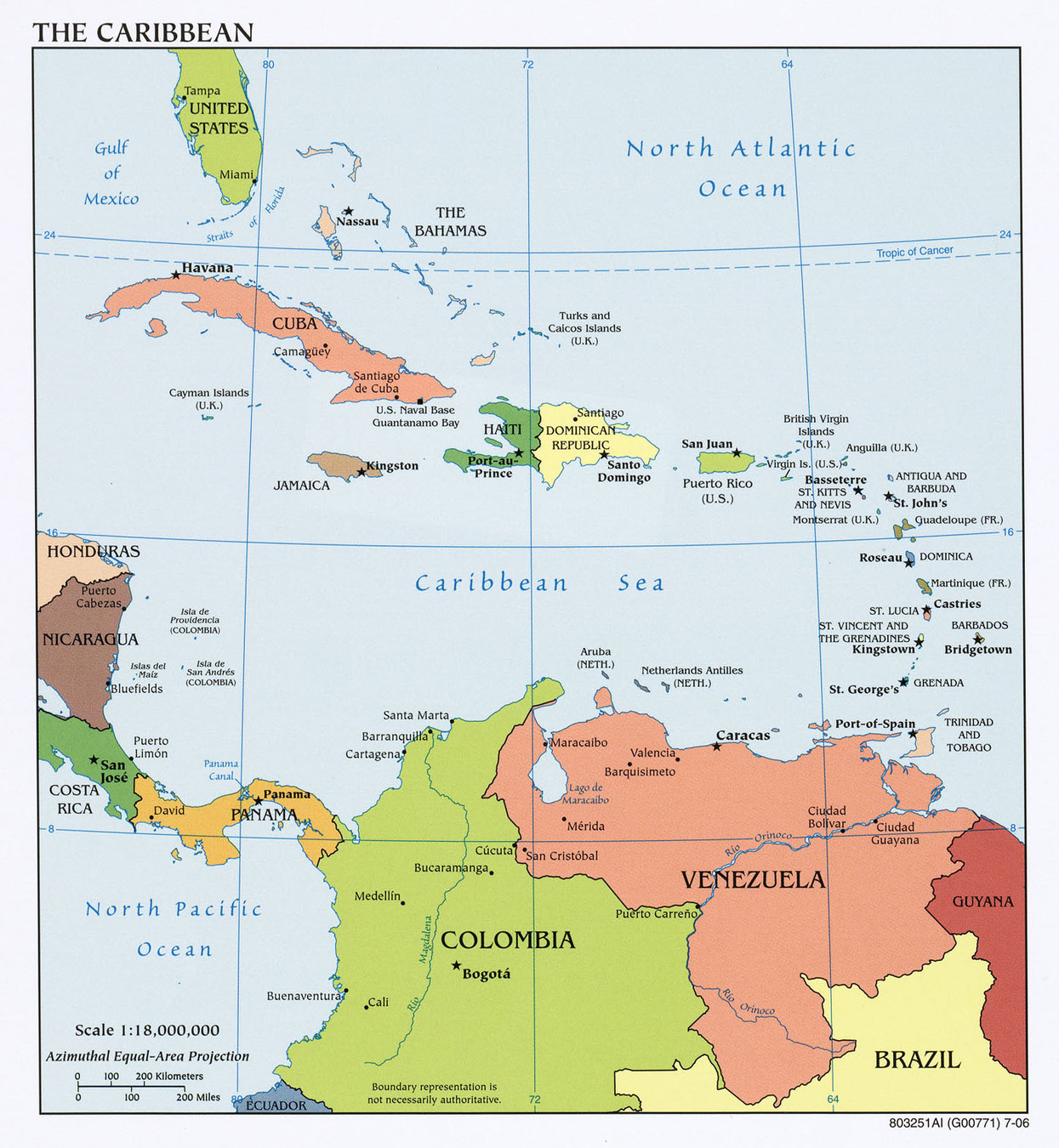

Optional Map Activity: Locate Fiestas!

Left: The Caribbean (Political), by U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. University of Texas Libraries. Above: Puerto Rico Blank Map, by David Harstad. The Harstad Collection.

-

Loíza

-

Ponce

-

Lares

-

San Juan

-

Comerío

-

Barranquitas

-

Mayagüez

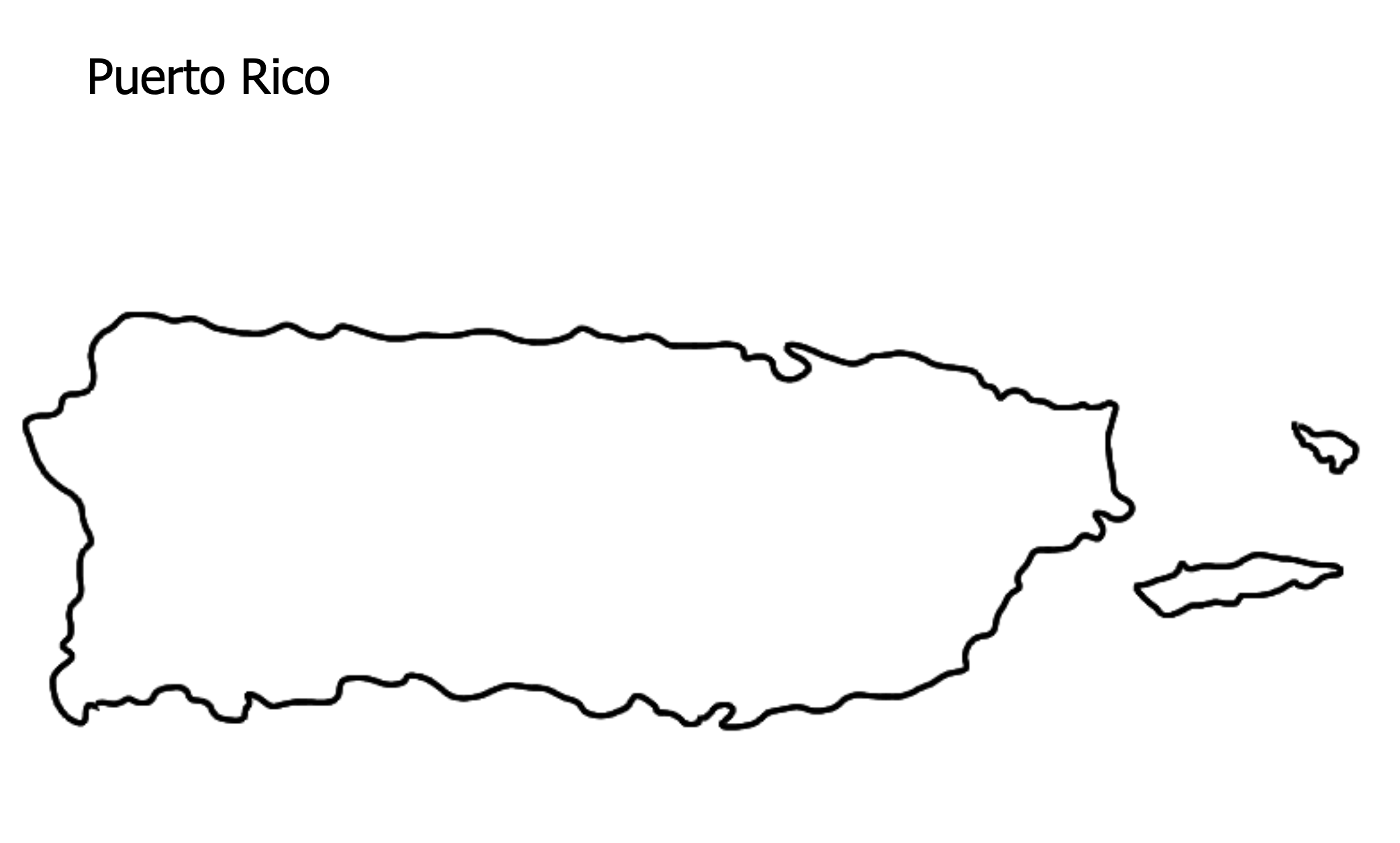

Map Activity: Locate Fiestas!

Map of Puerto Rico, by Daniel Feher, via freeworldmaps.net.

-

Loíza

-

Ponce

-

Lares

-

San Juan

-

Comerío

-

Barranquitas

-

Mayagüez

Fiesta in Historical Context: Aguinaldo

During the colonial period, Indigenous and African peoples embedded their beliefs into Catholic fiestas, which produced forms such as the aguinaldo: a local music that combines African, Indigenous, and European elements.

-

Aguinaldos are often performed at Christmas and are a key element of Epiphany rituals (known as Promesa de Reyes).

The Three Kings, by the Rivera Group. National Museum of American History.

Listen to Aguinaldo

Listen to an example of aguinaldo:

"Fiesta en el Batey" by the Grammy- and Latin-Grammy-nominated ensemble Ecos de Borínquen

El Alma de Puerto Rico: Jíbaro Tradition by Ecos de Borínquen, cover art by Galen Lawson. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

The Endurance of Traditional Fiestas

These traditional fiestas are key in sustaining a collective Puerto Rican identity.

Although not all Puerto Ricans are Catholic, many of the traditional fiestas of the Catholic liturgical calendar are still celebrated, both on the island and abroad, as part of national holidays (e.g. Christmas, Three Kings, Easter).

Christmas Parade in Condado, Puerto Rico, by Alan Kotok. CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

What recurring "fiestas" or holidays are celebrated in your culture?

Learning Checkpoint

-

What are the three main ethnic components of Puerto Rican culture?

-

How is this cultural blend expressed in Puerto Rico’s music and dance?

-

How would you define fiesta and what are three basic elements common to most Puerto Rican fiestas?

-

What are some of the recurring fiestas or holidays celebrated in Puerto Rico (and in your culture)?

End of Path 1: Where will you go next?

Exploring Fiesta as Religious Ritual and Secular Expression

Path 2

30+ minutes

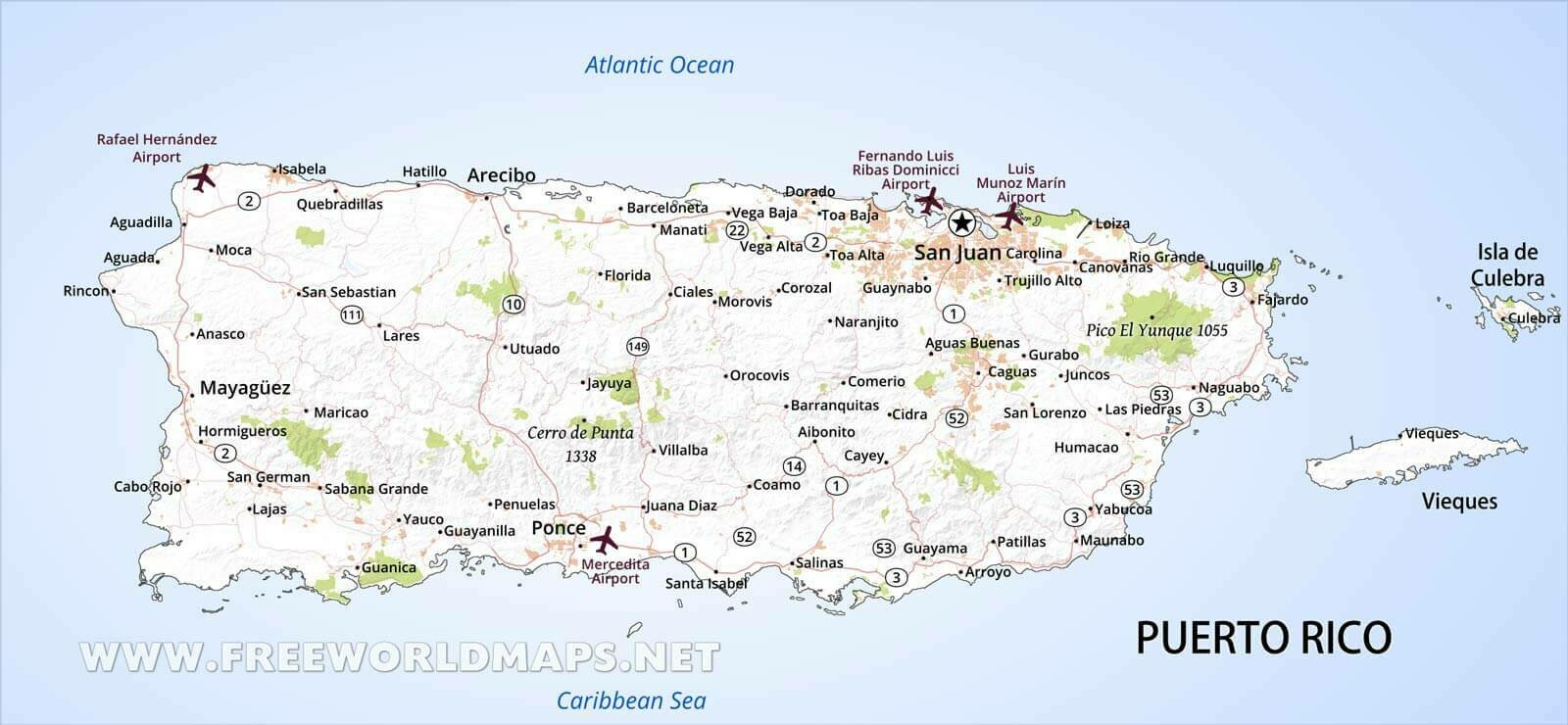

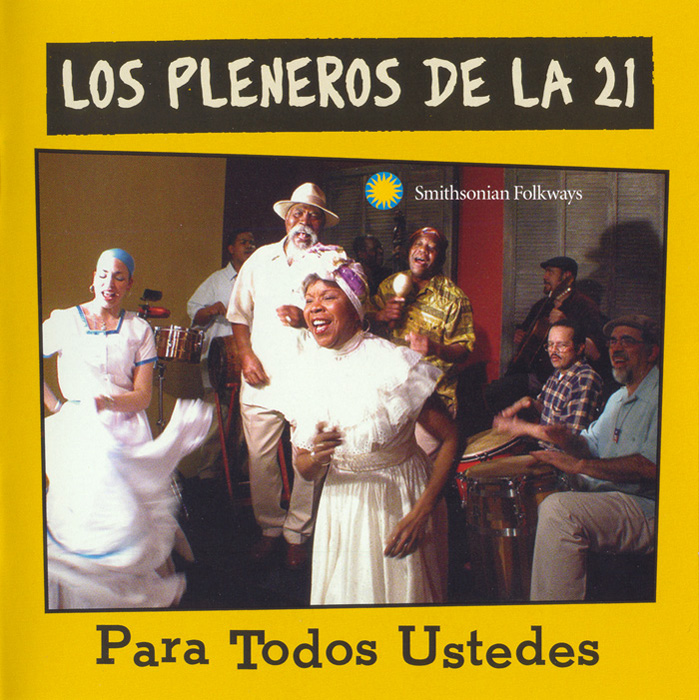

Para Todos Ustedes, cover art by MP Designs. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Fiesta as Religious Ritual

What do you notice about the structure of this type of fiesta?

Watch this fiesta video, featuring the Catholic celebration of Fiesta de Reyes.

What is a religious fiesta?

What do you notice about the environment?

What do you notice about the music?

Promesa Papo Capí y Maelo Vázquez, video by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

Fiestas as Secular Colonial Expression

Fiestas are also an important part of secular life (non-religious events).

-

During the Spanish colonial period in Puerto Rico, fiestas helped celebrate royal weddings, the birth of a member of the royal family, or the crowning of a king or queen (Fiestas Reales of 1747 for the crowning of Fernando VI of Spain, for example).

-

Such state-sponsored public events reaffirmed the existing hierarchies of colonial society.

Fernando VI de España, by Louis-Michel van Loo. ©Photographic Archive Museo Nacional del Prado.

Fiesta as Secular Expression

What do you notice about the music?

Los Pleneros de la 21 - "El Testigo" [Live at Smithsonian Folklife Festival 2005]. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Watch Pleneros de la 21's "El Testigo":

What do you notice about the structure of this type of fiesta?

What do you notice about the environment?

Religious vs. Secular Fiesta

Compare and Contrast: What are some of the similarities and differences between secular and religious fiestas that you noticed?

Hints!

1) Staged vs. less rehearsed

2) A public place vs. a home

3) Commercialized vs. community organized

But ... A Fiesta is So Much More

Even in traditional religious fiestas, the sacred and secular have coexisted side by side.

This famous painting, "El Velorio" (1893) by Francisco Oller, depicts several aspects of Puerto Rican fiesta. Can you identify some?

El Velorio, by Francisco Oller. {PD-Art (PD-old-70)}, via Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte de la Universidad de Puerto Rico.

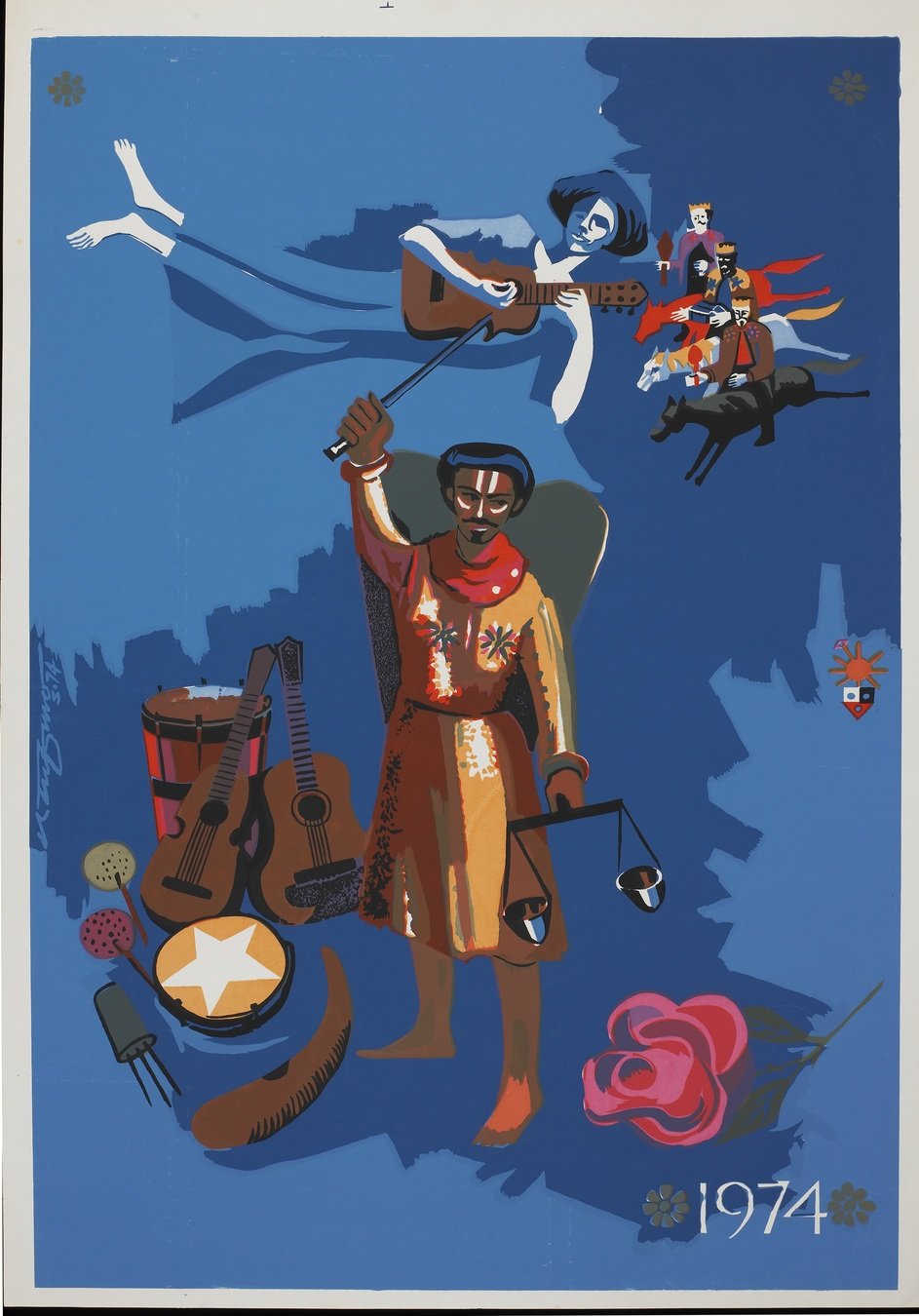

Calendar Reveal!

Puerto Rico's current calendar of fiestas and holidays is eclectic in character. It commemorates and celebrates events that are both secular and religious in nature:

-

Hispanic and Afro-Caribbean ancestry (Three Kings Day, Patron Saint Feast Days, Columbus Day, Fiesta de Cruz de Mayo)

-

National history (Grito de Lares, Día de los Proceres, Estado Libre Asociado)

-

US holidays (4th of July, Labor Day, Thanksgiving, Veterans Day)

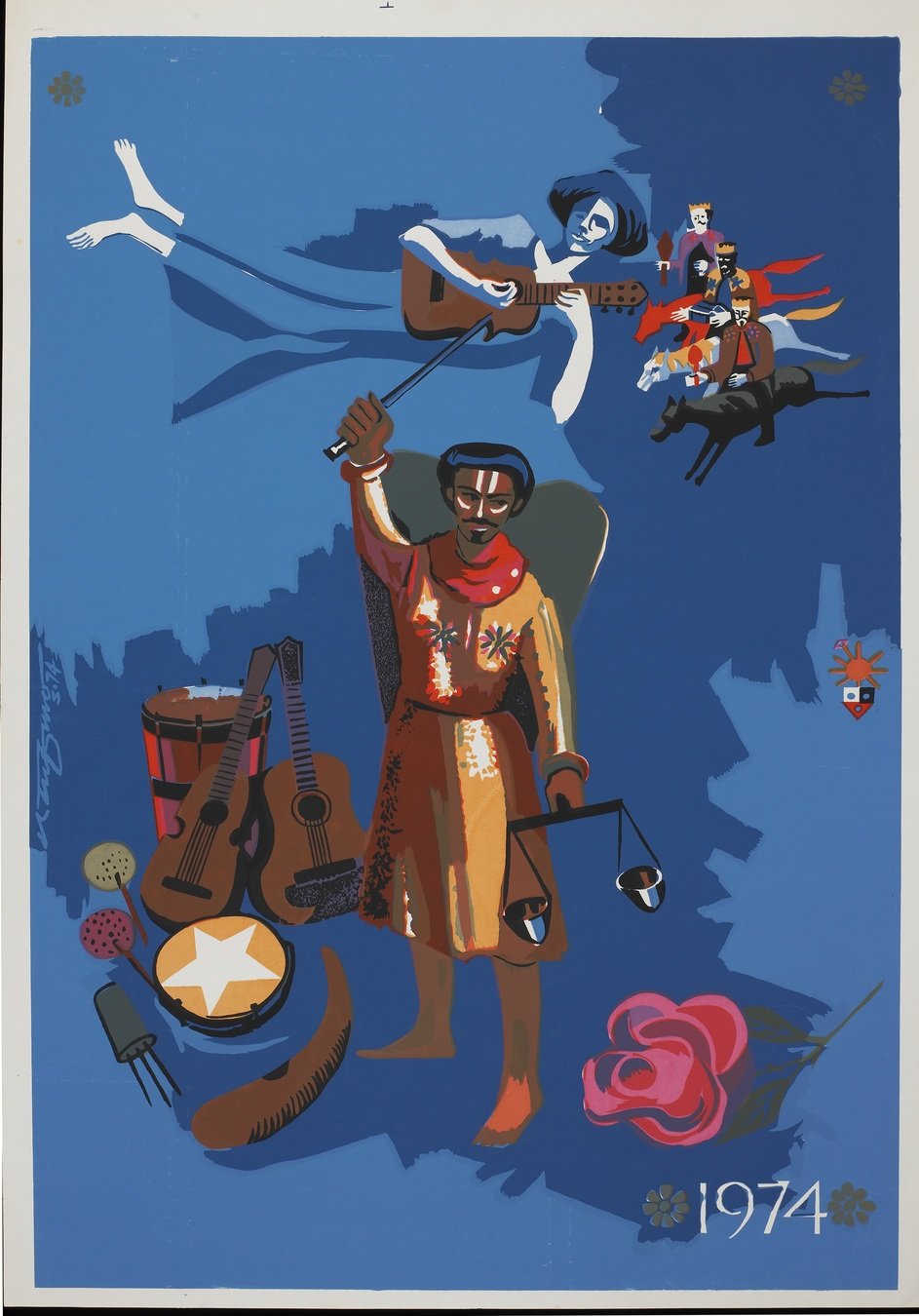

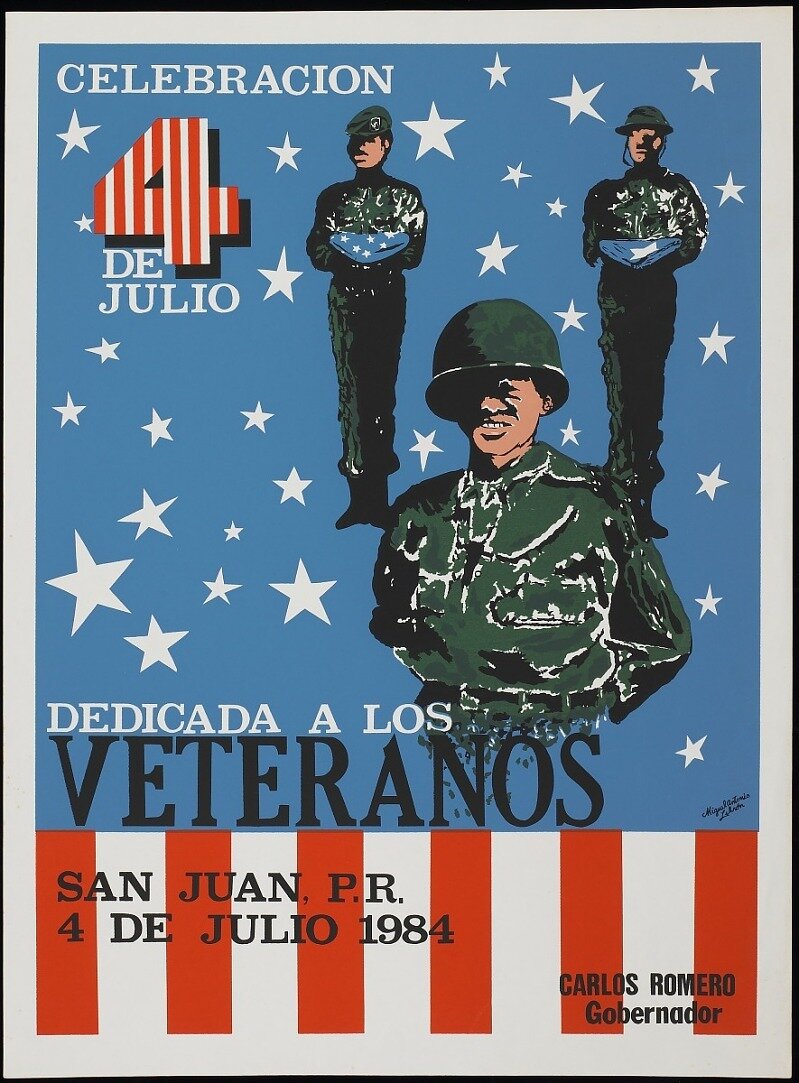

Above: Untitled Christmas Poster, by Rafael Tufino. Left: 4th of July Celebration Screenprint Poster, by Miguel Antonio Lebron. National Museum of American History.

Folk "Festivals" Flourish

While fiestas may have lost their strict connection to religious practices, they have gained significance in other ways by contributing to national and regional identity and folklore.

Many fiestas have become more and more secularized over time, due to modernization and industrial life.

As fiestas during the 20th and 21st centuries declined, folk and cultural festivals flourished.

Concurso de Trovadores en Barranquitas, Centenario de Luis Muñoz Rivera, 1959, unknown artist. CC BY-NC-SA 1.0, via Archivo General de Puerto Rico.

The Purpose of Festivals

Festivals (both within and outside of Puerto Rico) can be seen as vehicles to:

-

preserve local tradition

-

foster national pride and collective identity

-

recreate tradition within a non-religious context

The Puerto Rican Festival of Massachusetts 2017, unknown photographer. Courtesy of Puerto Rican Festival of MA.

Festivals as a Vehicle to Preserve Tradition

Vieques Festival 2008, Isabel II, photo by Katka Nemcokova. CC BY-SA 3.0. http://nemcok.sk/ , via Wikimedia Commons.

Festivals often involve staged performances.

- When recreating folklore, artistic decisions made for the purpose of spectacle are sometimes criticized.

- Some see these changes as misrepresentations that romanticize the folk traditions they are trying to imitate.

- However, festivals provide important opportunities for the continuation, recreation, and renewal of tradition.

The Importance of Long-Standing Cultural Festivals

As an example, Fiestas de la Cruz (Feasts of the Holy Cross) have been celebrated in Puerto Rico since 1787! The Afro-Puerto Rican music group shown here—Los Pleneros de la 21—has been celebrating the Fiestas de la Cruz in East Harlem, NY for 36 years.

Cultural festivals with long histories are essential to building community. They are often highly ritualized in terms of dress, performance, stage, and music.

Optional Listening Activity: "Fiestas de la Cruz"

Las Fiestas de la Cruz is a long-standing testament to key cultural expressions of Puerto Rico. This popular celebration of chanted rosaries is based on a Catholic tradition in honor of the Cross that Puerto Ricans inherited from Spain.

Listen to historic recordings of two songs that form part of the traditional repertoire sung at Fiestas de la Cruz: "Que Viva" and "Mayo Florida."

Blue Rosary, by Jeffries & Manz, publishers, {PD-scan|PD-old-70}, via Wikimedia Commons.

Concursos de Trovadores

Concursos de trovadores (poetic dual singing competitions) have a long-standing history at local festivals in Puerto Rico. Some of the earliest of the competitions date to the 18th and 19th centuries.

-

For over twenty years, the Bacardi Festival sponsored the largest and most prestigious concurso on the island, Concurso de Trovadores Bacardi, as well as an Artisans Fair.

Encuentro de Campeones Trovadores Bacardi 1984–1998, uploaded by Ramon Mirbon.

Local Festivals: The Lifeblood of Communities

Less formal, recurring events make up the life blood of local communities.

Community in modern contemporary life is always being redefined:

They eventually became key to building and directly serving those local communities.

Plenazo 3, photo by Angel Xavier Viera-Vargas. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr.

For example, plenazo and bombazo began as small informal events where people would play music (plena and bomba), drink, eat, and socialize.

Now, plenazo and bombazo have morphed into more formally organized events.

Local Festivals Promote Ecology and Tourism

Local festivals can also support tourism and ecology, and promote local produce!

Left: Leatherback Sea Turtle/Tinglar, photo by Claudia Lombard, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services. CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

Right: Aibonito Flower Festival 2013 First Prize Exhibit, by Jardin Boricua. CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr.

The Festival del Tinglar promotes conservation of the area and the leatherback turtles that return to the beaches year after year to lay their eggs.

The Important Role of Dance

Thus, dancing is an important part of most fiestas and festivals:

- Religious and secular

- Large and small

- Formal and informal

Dance is essential to Puerto Rican culture!

Rashelle Burns Dances at the Community Batey in La Perla, Puerto Rico, by Mariana Núñez Lozada. Smithsonian Folklife Magazine.

The Important Role of Dance

Local community events (such as bombazo and plenazo) have also been recreated into festivals and serve as spaces for people to dance.

Dancer and Musicians at the Community Batey of la Plaza del Negro, photo by Mariana Núñez Lozada. Smithsonian Folklife Magazine.

A rumbón de esquina (block party) is another occasion for people to dance bomba, plena, salsa, merengue, bachata, and others.

Bailoteo (from the word bailar, “to dance”), refers to nightclub-related music and dance known as música urbana.

Learning Checkpoint

-

Compare and contrast religious and secular fiesta in Puerto Rico. How are they different? What things do they have in common?

-

What distinguishes "fiesta" from "festival"?

-

Why are fiestas/festivals so significant for communities and participants?

End of Path 2: Where will you go next?

Fiesta as Identity in Puerto Rico and its Diaspora

Path 3

30+ minutes

Baile De Loiza Aldea, by Antonio Broccoli Porto. CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Fiesta Aquí, Fiesta Allá!

It is true that each municipio has its own way of celebrating (Puerto Rico is divided into 78 municipalities rather than states).

However, as the title of this pathway--Fiesta Aquí , Fiesta Allá expresses, "Puerto Rican" identity, culture, and community can transcend local differences.

Barriles and Cua, photo by Mariana Núñez Lozada. Smithsonian Folklife Magazine.

Fiestas fulfill a significant social role by bringing communities together to celebrate common ancestry and traditions.

What is Identity?

- Identity is instead porous: It may change over time to one degree or another.

- In other words, identity can be best understood as a process.

- No longer do we accept preexisting roles or structures that fix or define who we are into neat, fixed categories (e.g., man/woman; poor/rich; rural/urban).

Identity Word Hanging on Strings, by Matt Jeacock. iStock by Getty Images.

Recent interest in "identity formation" has revealed new ways of thinking about modern social life.

Syncretism: Blending Cultural Practices

In many ways, fiestas embody the diverse cultural mix that shapes Puerto Rican cultural traditions and identity:

- Indigenous (i.e., Taíno), African, and European elements have been synthesized and shaped into syncretic (blended) practices.

Identity formation in Puerto Rico involves the process of syncretism:

Combining competing belief systems and blending cultural practices.

Syncretism: A Sonic Example

"Ahora Si," by Viento de Agua

Feel and move to the rhythm of plena!

Plena music, which is often played at Puerto Rican fiestas, provides a sonic example of this idea.

As you listen and engage with the music, consider:

Why is plena a syncretic tradition?

Fiesta as Religious AND Secular

Many traditions rooted in Catholic tradition are still widely practiced in Puerto Rico as secular events.

An Example:

Fiesta de la Calle San Sebastian is a large festival which draws thousands of people to the streets of Old San Juan.

Now celebrated primarily as a commercial and tourist event, participants are more interested in experiencing the carnivalesque atmosphere and the artisan fair than they are in paying homage to San Sebastian.

Old San Juan Puerto Rico Fiestas De La Calle San Sebastian, ID 235400585. © Edgardo Cuevas|Dreamstime.com.

Fiesta as a Cultural Mosaic

In Puerto Rico, syncretism refers to the fusion of Christian beliefs with those of local native and African peoples.

- As you have seen, this fusion of beliefs and practices is especially obvious in music and dance, which are central elements of fiestas.

- The cultural mosaic represented by fiestas also includes other important aspects of Puerto Rican culture, such as language (e.g., literature) and cuisine.

Christmas: A Modern Syncretic Tradition

Christmas in Puerto Rico is a prime example of a modern syncretic tradition.

Puerto Ricans celebrate Christmas Day with Santa Claus, the reindeer, and gifts

More gifts arrive on Three Kings Day on January 6th

Untitled Christmas Poster, by Rafael Tufino. National Museum of American History.

Fiestas Can Challenge Social Norms and Present Alternative Perspectives

Though primarily entertainment, fiestas and festivals in Puerto Rico also provide avenues to:

- critique social norms

-

present alternate perspectives on certain issues, such as:

- race

- gender

- sexual orientation

- identity

Poor People's Campaign DC 2018, by Susan Melkisethian. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr.

Competing Political Ideology in Fiestas

Fiestas and festivals are also sometimes driven by political interests.

Pandero with Puerto Rican Flag, by Juan O'Halloran.

Advance through the next several slides to learn more ...

Understanding the Political Status of Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico has been a US colony since 1898.

Political debate in the island centers on whether Puerto Rico should be an independent nation, become part of the United States, or maintain its status under US protection with a certain degree of autonomy, an Estado Libre Asociado (Commonwealth).

Crowd in San Juan Plaza Listening to Speech in 1901 (Ceremony, Parade), by Helen H. Gardener. National Museum of Natural History.

Understanding the Political Status of Puerto Rico

Officially, Puerto Rico is an unincorporated territory of the United States:

- Neither a sovereign nation nor a US state

- Puerto Ricans are US citizens, but cannot vote in US presidential elections.

Puerto Rico and United States Flag, by Lee Cannon. CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr.

Puerto Rico and the US: A Complicated Relationship

Scholar Alvita Akiboh sums up Puerto Rico’s complicated relationship with the US in the following way:

Some Puerto Ricans favor statehood because they feel that if Puerto Rico is going to stay under U.S. rule, Puerto Ricans deserve to have the same rights as other U.S. citizens—Puerto Ricans today still cannot vote for the President, have no voting representatives in Congress, and yet can be conscripted into military service..."

Group of Young Girls in Costume and With American Flags in Street 1901 (Ceremony, Parade), by Helen H. Gardener. National Museum of Natural History.

Puerto Rico and the US: A Complicated Relationship

"... However, others fear that statehood would result in a loss of Puerto Rican identity and culture—especially Spanish language. Some Puerto Ricans favor independence in theory, but think it would certainly mean failure since they believe Puerto Rico’s economy is too fragile and its politicians too corrupt to function without the help of the United States. In the mainland, opinions vary as well. Some welcome the idea of a 51st state. Others, despite the fact that the United States has no official language, oppose the idea of admitting a state with a majority Spanish-speaking population. Meanwhile U.S. corporations with interests in Puerto Rico prefer continued colonial status, because it provides more opportunities for profit than statehood or independence."

Patriotism and Fiesta

Cultural events in Puerto Rico that are state sponsored—by organizations such as ICP (Institute of Puerto Rican Culure)—promote cultural awareness, exalt patriotism and "puertoricanness," without taking a clear political stance.

Mascaras de Hatillo, Puerto Rico, photo by Joe Delgado. CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr.

Political Ideology Promoted through Fiesta

Other fiestas and festivals organized by groups that favor independence are prime examples of events where political ideology is overt, intentional, and even militant.

Puerto Rico No Se Vende, photo by Eric Purcell. CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr.

This photograph was taken in New York at the 2017 Puerto Rican Day parade.

What is Meant by "Diaspora?"

The term “diaspora” refers to social groups that have scattered voluntarily or forcibly away from their original geographic locale.

It is commonly used to describe any national, ethnic, or cultural group of people who strongly identify with a homeland (e.g., Puerto Rico), but live outside of it (e.g., New York).

Fiestas Spread with the Puerto Rican Diaspora

At the turn of the 20th century, cities became centers of industry. Many Puerto Ricans migrated to urban centers in Puerto Rico and the United States for better job opportunities.

These groups still carried on their traditions (which of course included the observation and practice of fiesta!).

Street with Business Establishments, Puerto Rico, photo by H.A.S. National Museum of American History.

The Puerto Rican Diaspora in the United States

Today, almost 6 million people of Puerto Rican descent live in the rest of the United States. Many of these people are 2nd and 3rd generation migrants who are still passionate about their Puerto Rican heritage.

Sea of Flags, mural by Gamaliel Ramirez, photo by Jason Morris. Mural at Humboldt Park, Chicago, IL.

Fiesta Also Links Communities!

Many contemporary fiestas in Puerto Rico draw members from the diaspora community.

Other fiestas and festivals are celebrated simultaneously in locales on the island and the diaspora!

Puerto Rican Day Parade, New York City, 1987 (Tito Puente, Grand Marshal), unknown photographer. National Museum of American History.

Fiesta as Identity Spreads through the Arts

Throughout history, sounds and characters of "fiesta" have inspired many films, literary works, symphonies, visual arts, plastic arts, and performance arts. This representation in popular global culture helps to build and sustain Puerto Rican identity aquí and allá!

The Protagonist of an Endless Story, by Angel Rodriguez-Diaz. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Rita Moreno, by ADÁL. National Portrait Gallery.

Creative Connections Choice Board

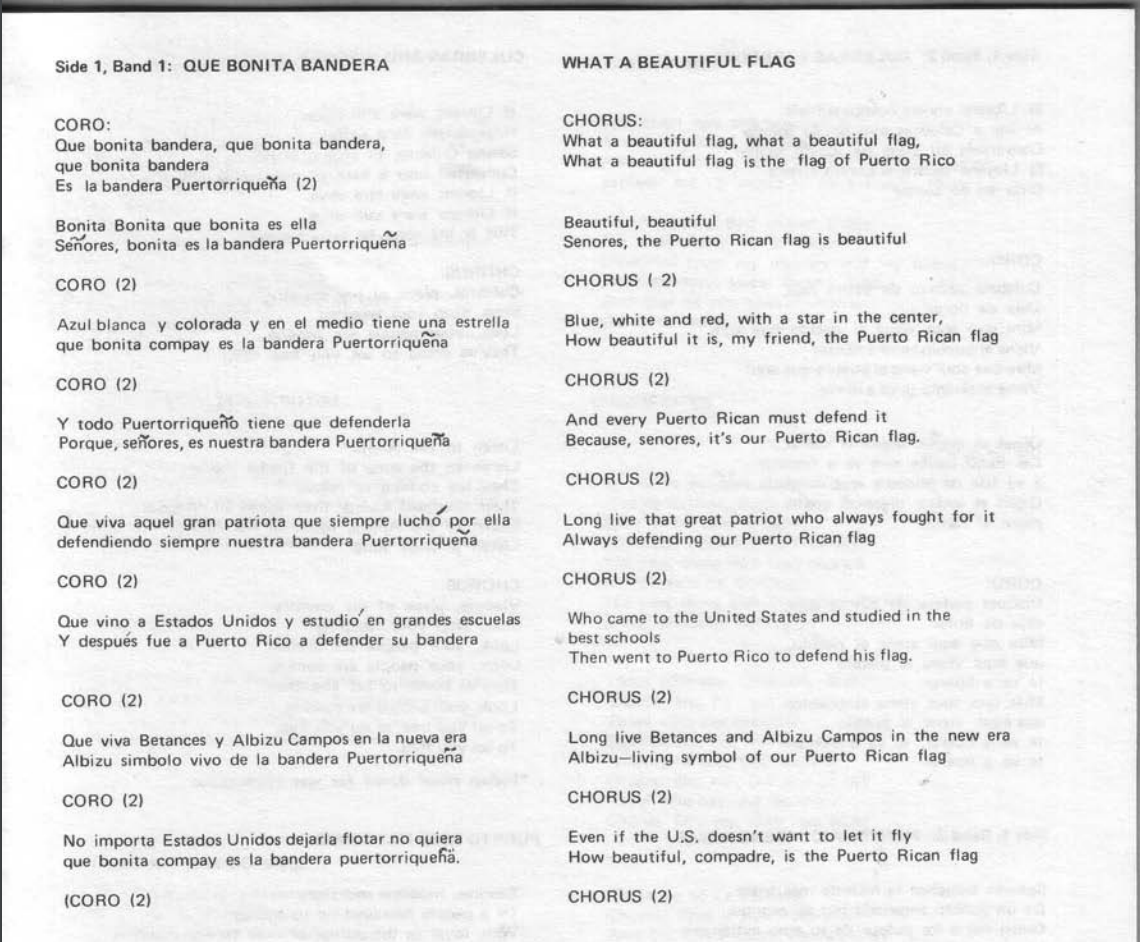

Listening Activity: Political Ideology in Music

Music plays an important role in fiestas/festivals, and therefore, music at these events has sometimes been used to express dissatisfaction with Puerto Rico's status as a territory of the United States and/or a desire for independence. Listen to this example, while following along with the lyrics.

What message are the musicians trying to convey?

"Que Bonita Bandera," performed by Pepe y Flora

Research Music and Dance as Activism

Throughout history, music has been used to subvert the social order, critique social norms, and/or provide alternative perspectives. Here are some examples in the Puerto Rican context:

-

Carnaval is sometimes described as a sonic occupation of a city. Societal rules are suspended as loud music, fireworks, and large crowds fill the streets.

-

Bomba music was used by enslaved people during the colonial period to organize revolts.

-

Plena music, sometimes called the “voice of the people,” has a longstanding history of commenting on social events and the struggles of the working class.

Time for Personal Reflection

- What are some important facets of your identity? How are these reflected through music?

-

Do you participate in/attend any cultural or ethnic festivals? Do these reflect your identity in any way?

-

What different ethnic groups and communities live in your area?

-

Do you know of other diasporas? Are you a part of a diaspora?

Learning Checkpoint

-

What is syncretism and why does it contribute to a collective "Puerto Rican" identity?

-

What is diaspora?

-

Why is the relationship between Puerto Rico and the U.S. "complicated" and how is this reflected in fiesta (and music)?

-

How do fiestas/festivals promote “puertoricaness” or shared identity among Puerto Ricans aquí and allá?

End of Path 3 and Lesson Hub 1: Where will you go next?

Lesson 1 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Library of Congress

Video courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Jaime Bofill

Images courtesy of

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Michelle Ramirez

Library of Congress

Smithsonian Folklife Magazine

National Museum of African American History and Culture

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

The Harstad Collection

Juan O'Halloran

Jason Morris

National Museum of American History

© 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This Pathway received federal support from the Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 1 landing page.

Puerto Rican Festival of MA

National Portrait Gallery

University of Texas at Austin, PCLP Map Collection

Daniel Feher, www.freeworldmaps.net

Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte de la Universidad de Puerto Rico

Museo Nacional del Prado

Archivo General de Puerto Rico