Regular Expressions

a tech talk by Don Smith

for Earthling Interactive

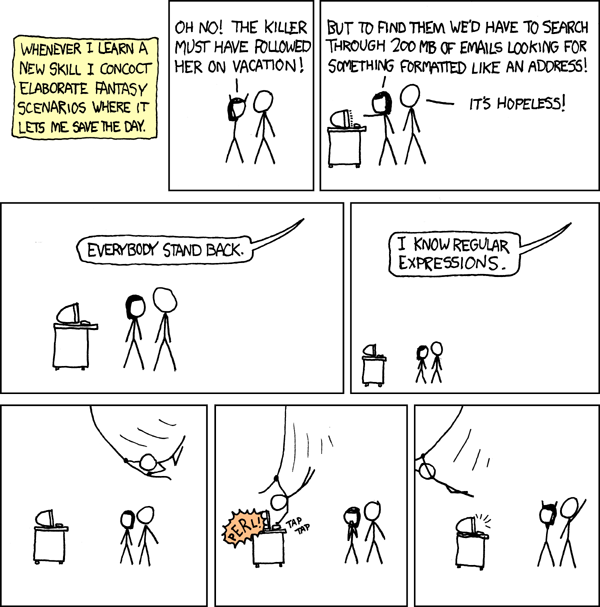

https://xkcd.com/208/

© Randall Munroe

What is a regular expression?

basically, it's a pattern used to match text

Does "Hello, World!" match /#[A-F0-9]+/

No.

Does "#3FA6B9" match /#[A-F0-9]+/

Yes!

Regular Expressions or RegEx are a formal way of describing these patterns.

Some people, when confronted with a problem, think "I know, I'll use regular expressions." Now they have two problems.

— Jamie Zawinski

Where Would I Use RegEx?

Some places where regular expression excel are...

- Data massaging/normalizing

- Tokenizing

- Validation

- Make all numerical values have thousands separators, or not.

- Create URL slugs.

- Use as part of a larger parse to easily match tokens.

- Does this value resemble an email address*? phone number? etc.

- Is this a value a valid IP address?

- Does a password violate a rule?

- Interactive "Play"

- RegEx is a great way to experiment with data via interactive tools and editors.

* This cuts both ways (see next slide) and the Robustness Principle applies.

Where Should I Avoid RegEx?

Some places where regular expressions fall down...

- Parsing*

- Some Validation

- Mission-Critical Unattended Processes

- Parsing markup is a common want. RegEx is a very poor choice.

- Likewise, JSON or other serialization formats. Tokenize with Regex

- RegEx for email address validation is common, but is very hard.

- It's easy to wrongly reject valid input because of your assumptions.

- Hands off processes with real-world input can fall apart.

- Making data look nice is fine. Taking critical actions based on massaged data can have consequences.

* strictly speaking, many modern regex engines can parse, because they're no longer "regular". That way madness lies.

I already know a whole bunch of

string manipulation functions,

why would I use RegEx?

because like so many* problems, text

processing is harder than it appears,

and it's been solved.

Don't reinvent the wheel. Michelin's got that dialed in already.

*all

We're good, bro!

Fact: text processing is hard

We start our text processing out nice and simple:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit

amet IMAGE:http://www.site.com/images/lolbutts.png

consectetur adipiscing elit.But things can quickly grow out of hand:

$start_position = strpos($document, 'IMAGE:') + 6;

$end_position = strpos($document, ' ', $start_position);

$url = substr($document, $start_position, $end_position - $start_position);What if $start_position wasn't a match?

Or... what if $end_position wasn't a match?

And... what if we're now indexing into strings with garbage values and the results... ACTUALLY MATTER?

$start_position = strpos($document, 'IMAGE:');Let's make it easy on ourselves

Our RegEx based parsing solution provides:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit

amet IMAGE:http://www.site.com/images/lolbutts.png

consectetur adipiscing elit.- Fault tolerance (no string indexing with bogus values like false)

- Catches edge-case (EOL vs. ASCII 32 termination)

- Easily extensible (make it match LINK: as well as...?)

- A syntax that other developers can recognize and work with.

if (preg_match('/IMAGE:(?<url>[^\s]+)/', $document, $matches)) {

print "Our URL: {$matches['url']}\n";

}Alright, you've convinced me!

Where do I start?

There's a lot to cover, so we'll need to break it down. Let's work through it and take a look at:

- Metacharacters

- Character classes

- Quantification

- Greediness

- "OR"ing

- Grouping/Capturing

- Lookarounds

- Flags

Metacharacters: Escaping

Some characters mean different things in different contexts. We have to know what means what .

When you want to match a literal metacharacter, you must escape it. Escaping is handled by prepending a backslash.

For example, if you want to match a literal period, you would use:

\.

Metacharacters

Some characters mean different things in different contexts. We have to know what means what.

.

The period is a very common

metacharacter in regular expressions.

It means "anything", though "anything"

can have different meanings

(is a line break "anything"?*)

For the most part, let's just assume it means any "normal" glyph, like "A" or "3" or

even an actual "."

* Sometimes

Metacharacters: Classes

Some characters mean different things in different contexts. We have to know what means what.

[ ]

brackets (or "square brackets") are used to define character classes.

Metacharacters: Quantifiers

Some characters mean different things in different contexts. We have to know what means what.

+ *

Plus and star (asterisk) are quantifying characters. They indicate repetition of the preceding thing. They can combine with the question mark to decide how greedy they are.

Plus means: the preceding thing occurs one or more times.

Star means: the preceding thing occurs zero or more times.

Metacharacters: Laziness

Some characters mean different things in different contexts. We have to know what means what.

?

The question mark usually indicates the preceding thing is optional.

When combined with a quantifier, it determines "greediness".

Metacharacters: Range Quantifiers

Some characters mean different things in different contexts. We have to know what means what.

{ }

braces (or "curly braces") are used to quantify as well, and allow you to bound repetition.

Metacharacters: Alteration

Some characters mean different things in different contexts. We have to know what means what.

|

Vertical bar or pipe allows for alteration (Boolean "OR" logic)

Metacharacters: Grouping

Some characters mean different things in different contexts. We have to know what means what.

( )

Parentheses are used for grouping and capturing.

Metacharacters: Anchors

Some characters mean different things in different contexts. We have to know what means what.

^ $

Caret and dollar sign allow you to anchor your expression. The caret anchors to the start* of the matched text, and the dollar sign matches to the end*.

* though as we'll learn, "start" and "end" can have different meanings.

Metacharacters: Escaping

Some characters mean different things in different contexts. We have to know what means what.

\

Backslash is used to escape metacharacters, thus making it a metacharacter itself. If you want to match a literal backslash, you must use \\

Metacharacters: Avoiding Escaping

Foreslashes are typically used to quote regular expressions. This means a foreslash in a regex needs to be escaped (think matching file paths). Most regex implementations allow for alternate quote characters to make your expressions tidier. Consider these two approaches.

/\/some\/path\/to\/a\/file/!/some/path/to/a/file!Standard foreslash quoting:

Bang quoting:

Metacharacters: Hex & Unicode

Some characters mean different things in different contexts. We have to know what means what.

\xAF

We can specify the value of a character using either a hex (ASCII) code with \x or a unicode code point with \u.

\u1234

\p{Property}

Character Classes

Character classes are built using square brackets [ ]. A character class allows us to specify a list of values, including ranges, that can be matched. If a dot will match any character, a character class will match a specific subset of characters.

Inside of square brackets we list the characters we want to match, or define ranges. When we're inside of a character class, we're in a new context and introduce a new metacharacter for defining ranges: the hyphen or dash.

-

Character Classes: Ranges

If we wanted a character class that would only match the first six letters of the alphabet, we could define it as follows:

[ABCDEF]Because these values are sequential, we can more succinctly define them using a range:

[A-F]By default this only matches uppercase letters. We can perform a case-insensitive match, but maybe case sensitivity is important in the broader expression, but we want to match any upper or lowercase letter. We could define our class as:

[A-Fa-f]Character Classes: Ranges

If we want to include a literal dash in a character class we can do one of two things.

- Escape it:

- Make it the first or last item in the class:

[A-F\-a-f]

[A-Fa-f-]

Because ranges require a start and an end value, having the dash either at the front or back of the class removes its special meaning.

Negated Character Classes

Sometimes we don't want to match a value in a list. Instead we want to match something not in the list. For this we can use a negated character class. Negated character classes have a caret ^ at the start of the character class. If you want a literal caret in a class, you can use a backslash to escape it, but you can also avoid making it the first item in the class*.

* unless you only want a caret in the class, in which case, why are you using a character class!?

If we want to match any character that's not one of the first six letters of the alphabet, we could use:

[^A-Fa-f]Character Class Shorthands

As you work with regular expressions you'll find yourself often using the same character classes over and over. Many, but not all, regex implementations provide shorthands for common character classes. Here's a list of some common ones and their class analogs:

| Class | Shorthand |

|---|---|

| [0-9] | \d |

| [^0-9] | \D |

| [A-Za-z_] | \w |

| [^A-Za-z_] | \W |

| [ \t\r\n\f] | \s |

| [^ \t\r\n\f] | \S |

Character Class Shorthands

Shorthands themselves can be used within character classes. So we could match hexadecimal digits with either or

[0-9A-F][\dA-F]An existing character class shorthand could be expanded as well: or

[0-9A-Fa-f_:-][\w:-]Caution: Weirdness

Despite their arcane syntax, regular expressions are built on fairly intuitive constructs. Once you break an expression down into its constituent parts it makes sense. So far we've talked about matching characters, but there are odd bits that allow for greater expression.

\bThis is the word boundary anchor. It's in a group with anchors like ^ and $. It doesn't match a "thing", it matches the space between things. Specifically, it will match

between a word (\w) and non-word (\W) character. It's called a zero-width anchor because it matches zero characters.

Quantifiers

Where the metacharacter dot and character classes allow us to specify what we want to match, quantifiers allow us to define how many times something should occur.

A plus sign will match whatever preceded it one or more times. A star will match whatever preceded it zero or more times.

| Pattern | Text | Matches? |

|---|---|---|

| [A-Z]+ | "ABCDEF" | Yes |

| [A-Z]* | "ABCDEF" | Yes |

| [A-Z]+ | "" | No |

| [A-Z]* | "" | Yes |

Range Quantifiers

Sometimes we want to be more explicit in quantifying our ranges. Curly braces give us an expressive way to define upper and lower bounds for repetition.

We can specify repetiton bounds as follows:

{4}{4,}{4,7}Match the preceding thing exactly four times

Match the preceding thing four or more times

Match the preceding thing between four and seven times

Suppose we wanted to match a social security number. We could use a pattern like:

[0-9]{3}-[0-9]{2}-[0-9]{4}Quantifiers: Optional

The question mark, in its basic form, makes the preceding something optional. So, if we had an expression like:

fizz?It would match either "fizz" or "fiz". The question mark means the second "z" is optional. This is a shortcut for a more explicitly defined bound. We could also express this concept as:

fizz{0,1}Greedy vs. Lazy Quantifiers

Quantifiers are greedy by default. What this means is that they will match the most text they are capable of. If we had an expression like:

And matched it against a string like "fizzbuzz", it would match the whole string. A question mark after a quantifier makes it a lazy quantifier. Lazy quantifiers will match the fewest characters possible. So, if we have an expression like:

It will only match the first "f" in "fizzbuzz". That's the minimum it can match and still satisfy the character class.

[A-Z]+[A-Z]+?"OR"ing

Often you want to indicate that two or more things are valid matches for a regular expression. The vertical bar character allows us to create boolean OR expressions.

Let's say we're trying to match genders in some text and want to catch a variety of expressions such as male, female, man, and woman. We could construct an OR expression as follows:

Female|Male|Women|MenGrouping/Capturing

Grouping/capturing is done with parentheses. Grouping allows us to contain and isolate matches and is often used with "OR"ing. By default, a group is also captured. This is one of the most powerful features of regular expressions. Captured values are retained and can be later pointed to using a back reference in the expression, returned in a matches array/hash, or used in subsequent replacements when you perform a regular expression find and replace.

(Female|Male|Women|Men)Capturing: Back References

Let's look at a few examples of capturing and how the captured values can be used.

(Female|Male|Women|Men)\1In this expression, we use the back reference \1 to serve as a placeholder for whatever was matched in the first capture group. This expression will match any of the following in text:

MaleMale

FemaleFemale

MenMen

WomenWomen

Capturing

<([A-Za-z]+)[^>]*>[^<]+<\/\1>The preceding example is not especially useful. A more practical example might involve matching opening and closing tag pairs in markup*.

The expression:

Would successfully match any of the following:

<strong>here's some text</strong>

<div class="col-xs-12">Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet</div>

<span ng-repeat="n in names">{{ n }}</span>* do not attempt to parse markup with regex!

Capturing

Whether you're using regex in an application, in your code editor, or on the command line there are typically one of two things you're trying to accomplish:

- Determine whether something matches a pattern.

- Extracting (and possibly manipulating) useful data from larger blocks of text.

Capturing is critical to that second task. Our parentheses group and capture values that can be used later. We've already seen back references used via syntax like \n where n is the index (one-based) of a previous group.

Capturing

Often we want to access captured values outside of the actual regular expression itself. Depending on the language or tool being used this can be accomplished several ways. If we had some PHP that looked like this:

$text = "Hello, World! This is some text!"

if (preg_match('/(T\S+).+?(\S+e)/', $text, $matches)) {

print_r($matches);

}The output would be:

Array ( [0] => This is some [1] => This [2] => some )We can see each of the pieces that matched. The zeroth element is what matched the entire expression, and the following two elements are the capture groups.

Named Captures

Being able to grab the tokens we matched is great, but accessing them based on the position can become a maintenance nightmare for large expressions where we may be adding more capture groups. A solution to this is named captures. Here's an example using named captures to extract a phone number.

$text = 'Please call, 608-867-5309 and ask to speak to Jenny.';

$regex = '/(?<area>\d{3})-(?<office>\d{3})-(?<line>\d{4})/';

if (preg_match($regex, $text, $matches)) {

print_r($matches);

}Array ( [0] => 608-867-5309 [area] => 608 [1] => 608 [office] => 867

[2] => 867 [line] => 5309 [3] => 5309 )The output would be as follows:

Named Captures: Backreferences

In some dialects, named captures can be used as backreferences.

Lorem stuff Lorem ipsum dolor sit (?<stuff>[A-Za-z]+).+?\k{stuff}We could use the following with a named backreference to match:

If we have the following text:

Caution: Named Captures

Caveat emptor! While named captures are really great, they have, somehow, managed to not make their way into native JavaScript regular expression implementations*. There are often libraries or shims that will provide the functionality in one way or another, but it is unfortunately not available out of the box.

This raises an important point about regex: know your implementation. While many languages use so-called PCRE (Perl Compatible Regular Expressions), it's important to be aware of the limitations and quirks of your tool or language.

* if you know otherwise, please say so.

Non-Capturing Groups

Sometimes you just want to be able to lump things together and don't actually need to retain values. Sometimes you lack named captures and want to group portions without consuming match indices. The solution is a non-capturing group.

$text = 'The best website is http://lolbutts.pizza/';

$regex = '/(?:https?|ftp):\/\/([^\/]+)\//';

if (preg_match($regex, $text, $matches)) {

print_r($matches);

}Array ( [0] => http://lolbutts.pizza/ [1] => lolbutts.pizza )The output would be as follows:

Lookarounds

Lookahead and lookbehind, known collectively as lookarounds, are similar to the anchors ^, $, and \b in that they're zero-width--meaning they consume no text--but are different in that they're comprised of sub-expressions.

There are four types of lookarounds:

(?=...)(?!...)(?<=...)(?<!...)Positive lookahead: the following thing occurs

Negative lookahead: the following thing does not occur

Positive lookbehind: the preceding thing occurs

Negative lookbehind: the preceding thing does not occur

Flags

Flags allow you to control how the regular expression engine behaves and treats certain parts of the regular expression. Not every implementation supports every flag so, as ever, get to know your tool. Flags are appended after the terminating foreslash. Here are a few:

/.../gGlobal: perform this operation globally, on every match.*

/.../iCase-insensitive: ignore letter case for matches.

/.../sSingle-line: makes . match new lines†

* not supported in PHP, use preg_match_all

† Not supported in JavaScript

/.../xFree-spacing: spaces and line breaks can be added for readability.

/.../mMulti-line: makes ^ and $ match new lines as well as start/end of string.

We Made It!

Whew! That's a lot to absorb, I know. But don't worry, you don't need to know all, or even most, of that to get started. Character classes and quantifiers are a great way to start using regular expressions and will serve you well.

While we've covered the guts of regex, there are some peripheral topics and tools worth exploring and we'll run through some of those now.

Usage In Your Language

Regular expressions are typically quoted with foreslashes. In languages like Perl and JavaScript where regex is native, you'll see them raw and unadorned in the code. Languages like PHP rely on external libraries and typically put regular expressions inside of strings. Be mindful of this, as it can sometime require double escaping things inside of strings.

my $string = 'Hello, World!';

$string =~ s/^([^,]+),\s+(.+)$/$2, $1/;

print $string;Perl

$string = 'Hello, World!';

$string = preg_replace('/^([^,]+),\s+(.+)$/', '$2, $1', $string);

print $string;World!, HelloPHP

Workflow

Most code editors support regular expressions. Learn how yours works (dialect or library) to make you more effective.

Many of the command line tools that grew up in Unix use regex. Grep, awk, and sed are common get-things-done tools for using regular expressions. Perl is also very powerful and to some degree sets the standard (PCRE) for regex.

Be aware of escaping on the command like. It's not uncommon to need to backslash escape through multiple contexts.

Workflow: Examples

Here's some sed used in a Vagrant provisioning shell script for TheReferralPad to update an Apache config:

Here's an awk example to get the process IDs of everything root is running:

sed -i "s/AllowOverride None/AllowOverride All/g" /etc/apache2/apache2.confps aux | awk '/^root/ { print $2 }'grep :$ /etc/passwdHere's a grep example to find users with no login shell defined:

Fun* Example

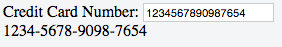

Format credit card numbers in JavaScript:

* "Fun" is a David Jolly reserved word. Please do not confuse with actual fun.

<label for="creditCard">

Credit Card Number:

<input type="text" id="creditCard" value="1234567890987654" maxlength="16" />

</label>

<span id="formatted"></span>var formatNumber = function() {

var ccNum = $('#creditCard').val();

var fmted = ccNum.replace(/(\d{4}(?!$))/g, '$1-');

$('#formatted').html(fmted);

};

$('#creditCard').on('change', formatNumber);

formatNumber();

This is really not an appropriate use of regex...

Interesting* Example

Find Email addresses with PHP:

* "Interesting" is a David Jolly reserved word. Please do not confuse with actual items of interest.

$text = <<<_TEXT

I was talking to joe@email.com and

also bill@hostname.com about

chris@lolbutts.pizza and we thought...

_TEXT;

if (preg_match_all('/(?<email>[^@\s]+@[^@\s]+)/', $text, $matches)) {

foreach ($matches['email'] as $idx => $email) {

print "$email<br>\n";

}

}Output:

joe@email.com

bill@hostname.com

chris@lolbutts.pizza

This example is actually "fun", not "interesting"

Yet Another Example

Parse /etc/hosts with Perl

#!/usr/bin/env perl

use strict;

use warnings;

use File::Slurp;

my $data = read_file('/etc/hosts');

while ($data =~ m/

^ # start of line

\s* # zero or more whitespace

(?<ip> # start a capture group named "ip"

# IPv4 matcher...

(?:(?:25[0-5]|2[0-4][0-9]|[01]?[0-9][0-9]?)\.){3}

(?:25[0-5]|2[0-4][0-9]|[01]?[0-9][0-9]?)

)

\s+ # one or more whitespace

(?<domain> # start a capture group named "domain"

[^\s#]+ # non-whitespace, non-hash, repeating, greedily

)

$ # end of line

/xgm) {

print "IP: $+{ip}\nDomain: $+{domain}\n\n";

}

Helpful Resources

www.regular-expressions.info

Excellent documentation. Great nitty gritty details and covers differences between languages/implementations.

regex101.com

Interactive syntax-highlighted editor. Tree diagram with explanation of behavior. Sample text box with match indicators.

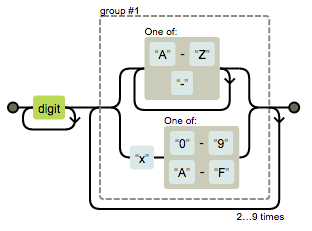

regexper.com

Generate railroad diagrams from regular expressions. An excellent visual way to see what the syntax actually does.

/\d+([A-Z-]+|x[0-9A-F]){3,10}/

Thanks for listening!

And staying awake*

* Just kidding, I know you didn't stay awake.

Regex Tech Talk

By Don Smith

Regex Tech Talk

- 32