Williams' Dictum

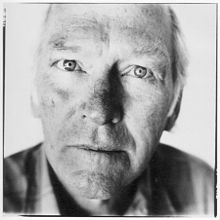

Joe Cunningham

Early Career Mind Network, Warwick

27/04/2016

Overview

1. The distinction between good cases and bad cases

2. (HCF) introduced

3. Williams' Dictum

4. Two versions of (HCF)

5. Responses to Hornsby & Roessler

6. A new argument against (HCF)

The Good Case

- There is a normative reason for S to Φ: the fact that p

- S knows that p

- S knows p to be a normative reason for them to Φ

- S Φs in a way that manifests such knowledge

- This underwrites the truth of a rationalising explanation of why S Φs producible using 'S Φs because p'

The Bad Case

- S believes that p

- S takes p to be a normative reason for them to Φ

- S Φs in a way that manifests such beliefs

- This underwrites the truth of a rationalising explanation of why S Φs producible using `S Φs because S Bp'

- S does not Φ in response to the normative reason that p

The Highest Common Factor View

-

The rationalising explanation to which S's Φ-ing is subject in the good case is, in some suitable sense, the same as the rationalising explanation to which their Φ-ing is subject in the bad case.

- It follows that we cannot simply identify responding to the normative reason that p with the explanation in the good case.

Davidson's Version of (HCF)

- Good case: S's belief that p is what explains why S Φs

- Bad case: S's belief that p is what explains why S Φs

- Responding to the normative reason that p factors into Φ-ing because SBp + p is a reason for S to Φ & S's belief is knowledge

Dancy's Version of (HCF)

- Good case: the fact (obtaining state of affairs) that p is what explains why S Φs, enabled by SBp

- Bad case: the non-obtaining states of affairs that p is what explains why S Φs, enabled by SBp

- Responding to the normative reason that p is a good case explanation but where p is known

Williams' Dictum

"...the distinction between false and true beliefs on the agent's part cannot alter the form of the explanation which will be appropriate to his action." (Williams 1980: 120)

Explanations vs. Kinds Thereof

(i) The tree collapsed because it was hit by a strong wind.

(ii)The left side of the man's face is numb because the dentist administered local anaesthetic to it.

(iii)The wall is hard because it is made out of brick.

(iv)The statue is has been destroyed because the clay from which it was made has been obliterated.

Same Kind

Same Kind

What is a Kind of Explanation?

A general way of making things intelligible. Examples include: causal explanations, constitutive explanation, (perhaps) teleological explanations, and rationalising explanations.

The kind to which an explanation belongs partly determines the answer to the question: how does the explanans of the explanation explain why the explanandum holds?

Two Readings of Williams' Dictum

"...the distinction between false and true beliefs on the agent's part cannot alter the form of the explanation which will be appropriate to his action."

Strong Reading: For every particular rationalising explanation, that explanation does not require p to be a reason in favour of S's Φ-ing

Weak Reading: For every particular rationalising explanation, that explanation is not of a kind which requires p to be a reason in favour of S's Φ-ing

Strong claim entails weak claim but not vice-versa

Two Readings of (HCF)

(HCF)-Strong: The particular explanation which holds in the good case also holds in the bad case.

(HCF)-Weak: The particular explanation which holds in the good case is different from the particular explanation which holds in the bad case, but they are of the same kind.

Clarifiction of (HCF)-Weak

- The particular explanation which holds in the good case requires for its truth that p is a normative reason for S to Φ, e.g. the fact that p or S's knowledge that p is the explanans. The particular explanation which holds in the bad case doesn't, e.g. the non-obtaining state of affairs that p or S's belief that p is the explanans.

- But how the explanans of each explanations makes the agent's Φ-ing intelligible is the same in both cases: by being a factor that constitutes the appearance of a normative reason for S to Φ. It's just that, in the good case, this role is played by a normative reason-involving condition.

Reply to Hornsby

- Hornsby (2008) argues that S Φs because p only if SKp. She infers from this that (HCF) is false.

- The inference is invalid because the proponent of (HCF)-weak can agree with Hornsby's epistemic thesis by allowing that it is S's knowledge that p which is part of the explanans in the good case, whilst denying that this is part of how the explanans makes the explanandum intelligible.

Reply to Roessler

- Roessler (2014) argues that in reasoning to the conclusion to Φ, it seems to the agent that they come to Φ in a way that is determined by what normative reasons there are. This is intended to tell against (HCF).

- Again, the proponent of (HCF) weak can allow that the explanation which holds in the good case takes as its explanans a normative reason, or a normative reason-involving condition, whilst denying that this is how it makes its explanandum intelligible.

A Fresh Argument I

- A standard good case: S goes to the cupboard in response to the fact that it contains chocolate. That it contains chocolate is a reason for S to go, she knows that fact and knows it to have the normative status it does, and acts in a way that manifests such knowledge.

- A variant involving akrasia: that the cupboard contains chocolate is a reason for S to go, but is a reason that's outweighed by the countervailing consideration that she's on a diet. Knowing all this, S goes to the cupboard anyway, thus manifesting weakness of will.

A Fresh Argument II

- In the standard case, the fact that the cupboard contains chocolate seems to S to exert its influence on S's will in so far as it is a reason for her to go. This is not the way things seem for S in the akrasia case.

- How to cash out this qua reason aspect? A natural suggestion: it seems to S that how the reason is motivating S is by being a normative reason.

- But for p to motivate S to Φ is for p to be (part of) the explanans of the rationalising explanation of S's Φ-ing. So this is tantamount to saying that how p gets to explain why S Φs, from S's own point of view, is by being a normative reason.

Williams' Dictum

By Joe Cunningham

Williams' Dictum

ECMN 27/04/16

- 91