A Question of Emphasis?

Identifying arguments in linguistic and multi-modal contexts

Steven W. Patterson

Marygrove College

25 April 2014

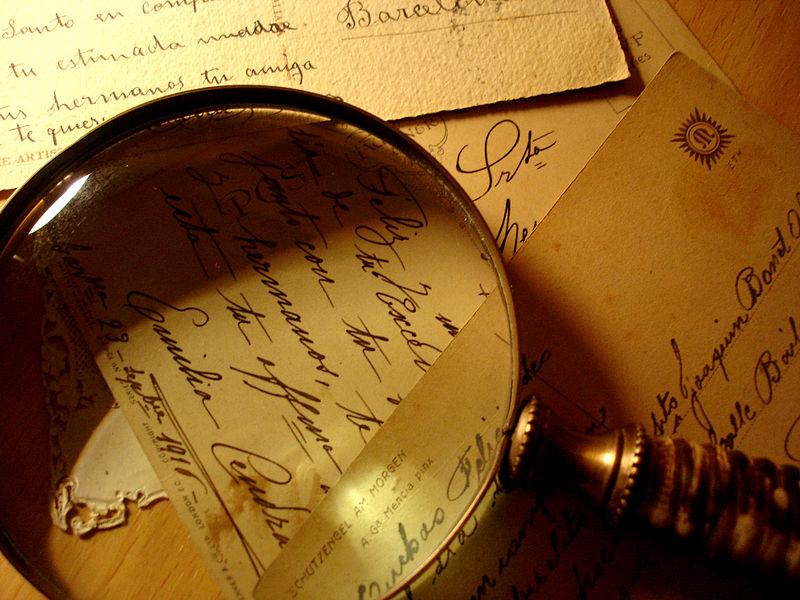

Image: Anna Sandstein via CC 2.0 license

Assumptions

(for now, at least)

- There are such things as multi-modal arguments.

- These arguments are susceptible to appraisal, analysis, and evaluation using the usual tools, concepts, and methods of informal logic and argumentation theory, i.e. "Normative Non-Revisionism" holds. (Godden 2013)

The Multi-Modal Challenge:

How do we move from the images, sounds, etc. together with whatever accompanying text there might be to:

that

One answer:

We do the job in the usual way...obviously!

Okay, but what way is that?

The Holy Trinity:

Linguistic Cues

Context Intentions

Linguistic Cues

The classic example of such cues are indicator words and phrases for premises and conclusions (e.g. 'therefore', 'assuming that', etc.). Other conventions of language may be useful in the same way.

As evidence of argumentation such cues are helpful, BUT:

- They aren't conclusive.

- They aren't always present.

Context

We typically approach context in two ways:

- In terms of exposing students to types of text where argumentation is more likely to occur (e.g. in letters to the editor sections of newspaper or comments sections on blogs).

- In terms of being able to recognize situations in which argumentation is more likely to occur (e.g. in deliberative settings, or in critical discussions).

Communicative Intent

Where we can attribute an intention to argue to a speaker or a writer we sometimes take this as increasing the likelihood that a given sample of language contains an argument.

Okay, so now that we know what to do,

let's apply our powers of argument identification!

Ready....?

GO!

Try Another:

Here's a fun one:

Did you spot the argument? I knew you could!

How Did You Do?

Probably you feel like you would have no problem at all coming up with arguments--maybe even multiple arguments--for each image.

You probably can.

The question is:

How, exactly, did the Holy Trinity help you do this?

- There were no indicator words, or other sorts of conventional linguistic cues in any of the images.

- Contextual considerations about type of text do not apply, nor is there an identifiable, interpersonal dialectical context in any of these cases.

-

In the first and and second images the communicative intention seems fairly clear, but knowing it doesn't help us at all to specify a particular argument. In the third image all we can do is guess when it comes to what the agent's intentions might have been.

Another Worry:

- building affective associations

- instigating (rather than presenting) argumentation

- explaining

- asserting

- illustrating

So How Did We Do It?

For our purpose, the important observation is that, even assuming we avoided the false positives problem and correctly identified arguments in the samples,

we did not get our argument out of the sample in the standard way.

But So What!?

- We have the same problems with arguments in natural languages.

- We have other resources to draw on in multi-modal contexts.

- (This is just code for skepticism about multi-modal arguments, which is clearly wrong-headed.)

Well, Here's What:

- If it's true that we have the same problems in natural language arguments then there's something clearly wrong with the idea of the Holy Trinity.

- If there are other cues in multi-modal presentations then that's great. What are they and how do they work, exactly?

- (Asking how we detect multi-modal arguments presupposes that they do exist. It isn't code for skepticism.)

- Normative non-revisionism has the consequence that a Trinity problem on the multi-modal side of the house implies a corresponding Trinity problem on the linguistic side of the house, too.

So, Now What?

It may be time to re-examine and broaden our notions about argument identification.

A Beginning: Four Temperaments

The Archaeological

The Intutionistic

The Intutionistic

The Hermeneutic

The Pragmatic

The Pragmatic

The Archaeologist

The Archaeologist

- believes that arguments are there, in a real sense, because someone in the past intentionally put them there.

- believes that finding arguments is about careful use of the proper tools, procedures and methods.

- is concerned to reconstruct arguments exactly as they were offered, with as little elaboration as possible.

- tends to work outward from inferential structure.

- is concerned with avoiding false positives, e.g. things that might look like arguments but aren't.

The Intuitionist

The Intuitionist

- believes that arguments are there in a real sense, regardless of explicit acts of argument creation.

- believes that finding arguments mostly is a matter of being able intuitively to see that they are there.

- works from a conception of the argument in its ideal form; of the argument as it should have been given, even if the source did a poor job (or no job at all!) articulating it.

- trusts in her intuitive faculty to distinguish between false positives and arguments.

The Hermeneut

The Hermeneut

- isn't really interested in whether or not the argument is there, in any real sense.

- doesn't so much identify arguments in passages of text (or images, or music, etc.) as take them to be arguments. Almost anything might be taken to be an argument.

- works more from a conception of what interpretations will be fruitful than from fidelity to the source or normative visions of the best version of the source's argument.

- is not concerned at all with false positives, as there are no such things.

The Pragmatist

The Pragmatist

- believes that arguments are there, in some real sense, only when people make (or have made) them.

- takes finding arguments to be a matter of rightly understanding the person who gives them, along both the semantic and pragmatic levels of analysis.

- works neither from structure, nor ideal form, nor from open-ended interpretation, but from the role the argument plays in its communicative context.

- is concerned with false positives, as falling into these would indicate a failure to understand the interlocutor.

So Who's Right?

Sorry, but I don't have a bloody clue.

But that's the wrong question anyway...

We can learn something from each of the four temperaments:

-

Archaeologists are right that evidence of some sort of discernible inferential structure is the best indication that an argument may be present.

- Intuitionists are right to distinguish there being an argument from an argument's actually having been made.

- Hermeneuts have a point that the exercise of interpreting a passage or a multi-modal source as argumentative is (to some degree) a choice that has to be justified.

-

Pragmatists are right to think that the argument might only emerge after sufficient understanding of the communicative context.

Five Questions for Identifying Arguments

- What justifies looking for arguments in the sample before us in the first place?

- What evidence is there that an argument is present in the sample?

- What alternative interpretations of this sample are most plausible? What justifies ruling them out?

- Does the evidence in the sample suggest particular features of a plausible linguistic reconstruction that would be suitable for the usual sort of analysis?

- After we have a reconstruction, is it something we can reasonably attribute to the source of our sample given the communicative context?

Interpretive Justification

- Is there a reasonable likelihood that the source intended to give an argument? (HT)

- Are there features of the discourse that indicate that arguments are likely to be found? (HT)

- Is the attempt to read the sample as an argument motivated by an attempt to understand the agent correctly? (Prag)

- Whose interests are served by parsing the sample as an argument as opposed to something else? (Herm)

Evidence

- Are there clear argument schemes or patterns of reasoning in evidence at the surface level? (Arch)

- Is there a clear dialectical obligation to show reasons being discharged by the agent who generated the sample? (Arch)

- Are there contextual considerations that motivate reading the sample as an argument as opposed to something else? (HT, Prag)

- Are there other features of the sample that seem to merit our taking it to be an argument, even if only provisionally? (Int)

Alternatives

- What other plausible, non-argumentative interpretations of the sample might there be? (Arch, Prag)

- What evidence is there for the alternative,non-argumentative interpretations? (Arch, Prag)

-

On balance, do the reasons and evidence on offer support the argumentative, as opposed to the non-argumentative interpretations of the sample? (Arch, Prag)

Reconstructability

- Are there conventional expressions or linguistic indicators that mark out clear candidates for premises or conclusions? (HT)

- In the absence of conventional expressions or linguistic indicators, is there any linguistic component that suggests itself as a premise or a conclusion, given the context? (Prag)

- If there are no linguistic components, what components will any reasonable re-construction of the argument have to have in order to be appropriately grounded in the sample. (Prag)

Attribution

- Does the re-constructed argument fit within the dialectical setting? (Arch)

- Is it plausible, in the context, that the agent would give this argument to this audience? (Prag)

- If is isn't, then it may be that what we have is an intuitionistic reconstruction of an ideal argument based on the sample, but that does not represent the argument as given.

- What are the consequences of attributing the re-constructed argument to the agent? (Prag, Herm)

- Interpretive Justification

Keeps us hammers from seeing everything as a nail. - Evidence

Keeps us grounded in the extant features of the sample before us. - Alternative Readings

Helps us maintain fallibility in our judgments. - Re-constructability

Tips us off to how much we are contributing to the product of our analysis. -

Attributability

Keeps us in-bounds with respect to the context in which the sample is found and keeps us alive to the dialectical consequences of our analysis.

Advantages

- Suggests the possibility of a single method of argument identification for both the linguistic and multi-modal cases.

- Expands but does not replace the "holy trinity" model.

- Incorporates instincts from all four "temperaments".

- (Hopefully) gives an idea of how the most powerful tools from the disparate branches of argumentation theory might be brought together into a single package.

Thank You!

A Question of Emphasis?

By Steven Patterson

A Question of Emphasis?

Slides for a Presentation to the Symposium on Visual Argumentation held by the Centre for Research in Reasoning, Argumentation and Rhetoric (CRRAR) at the University of Windsor in Windsor, Canada, in 2014.

- 906