Public Reason, Civic Virtue, and Dialogic Responsiveness

Song Academic Symposium

Marygrove College

20 March 2015

Outline

- A Tension for Political Liberals

- Religion vs. Public Reason

- Some Issues

- Re-framing the Problem

- Dialogic Responsiveness

1. Political Liberalism and Religion

Political Liberals (generally) tend to hold both of the following claims to be true:

Claim 1:

Religious liberty and freedom of expression are paradigmatic of the kinds of individual liberties that political liberalism aims to protect, promote, respect, and ensure.

Claim 2:

It is inappropriate for individuals in a pluralistic society to advocate for their preferred policies on the basis of their religious reasons.

So,

It is a core doctrine of political liberalism that freedom of expression and freedom of religion must be protected...

but...

...it is inappropriate for individuals to express religious reasons in public discourse...

If individuals have religious liberty and rights of free expression in the public sphere, then why can't religious people make arguments in the public sphere on the basis of their religious reasons?

The Short Political Liberal Answer:

Public Reason requires neutrality between conceptions of the good.

The clearest instances of judgments based on publicly accessible reasons are ones based on reasons whose force, rather than being a product of the particular person making the judgments, would be acknowledged by any competent and level headed observer. That logical deduction and scientific or ordinary empirical inquiry may involve judgments of this kind is fairly straightforward. . . . [A] principle that everyone should rely on publicly accessible reasons in making factual judgments for political decisions would presumably entail that people should give no more weight to their particular intuitions than could be defended in terms of persuasive interpersonal grounds for the present intuitions and the accuracy of past similar intuitions.

(Greenawalt 1998, 57)

2. Liberal Neutrality vs. Religion

-

Religious reasons aren't epistemically accessible by all.

-

Religious reasons do not (and cannot) address the polity as a whole--only fellow believers.

-

Impartiality is required when it comes to advocating for coercive policies (e.g. laws, etc.) in the public sphere.

- At least some religious beliefs (e.g. fundamentalist beliefs) seem to justify unjustly exclusionary/prejudicial coercive policies.

3. Some Issues with the Political Liberal Position

Two kinds of issues with political liberal neutrality:

- Conceptual

- Practical

Conceptual Issues

-

Political Liberalism itself may be a comprehensive doctrine with implicit commitments to a theory of the good.

- Procedural norms sanctioned under the canons of public reason may open to challenges of fairness too.

"Le Penseur" by Jean-David & Anne-Laure CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Practical Issues

-

Not all religious points of view are exclusionary. Are they acceptable in public reason or not?

-

Why would a religious person endorse political liberalism if it was effectively prejudicial against their preferred policies?

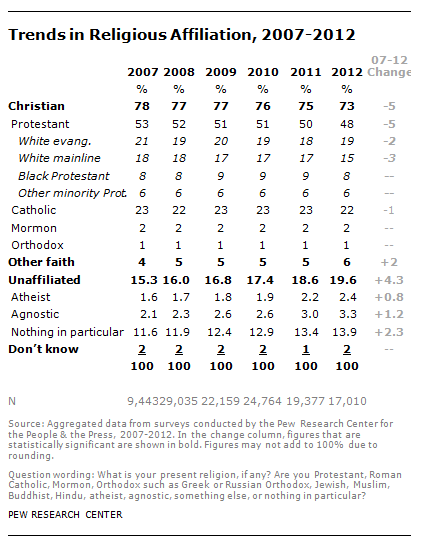

- We are talking about the U.S. here...

Source: Pew Research Center

http://www.pewforum.org/2012/10/09/nones-on-the-rise/

Principles of fairness...are principles used to guide social decision-making in circumstances where some members of society think justice requires one thing and other members of society think justice requires another. When fair political procedures indicate that one of these factions is to prevail at the level of social decision, the result will seem to the members of that faction to be congruent with justice, even as it seems to members of the other faction to be at odds with justice. This disparity...should alert us to the possibility that there is a 'category-mistake' in treating justice and fairness as co-ordinate principles, competing on the same level.

Waldron 1999, 195-6.

As alluring as [deliberative democratic] reasoning might be to many of us, it is difficult to imagine the fundamentalist's being much impressed by it--particularly when she learns that any empirical claims she makes must be consistent with 'relatively reliable methods of inquiry'. ...She will rightly expect to come out on the short end of any deliberative exchange conducted on that terrain. The [deliberative democratic] model works only for those fundamentalists who also count themselves fallibillist democrats. That, I fear, is an empty class, destined to remain uninhabited."

Shapiro 2003, 26.

What to do?

The value of neutrality seems important in a pluralistic society, but truly neutral frameworks are hard to construct.

4. Re-framing the Problem

(From a Rhetorical Point of View...)

The political liberal vision of public reason puts dissenters from its norms at an argumentative disadvantage:

Either

- their positions are prima facie unreasonable (logos),

or

- their motives are suspect (ethos)

The hope:

Addressing the rhetorical imbalance will prove more efficacious than either re-thinking public reason or attempting to ajudicate the reasonability of particular religious views.

The Proposal:

5. Dialogic Responsiveness

"The Meeting Continues", by Quinn Dombrowski, CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Some person, S, may be said to advocate for some policy, P, in a dialogically responsive manner if and only if the following conditions hold:

- S's advocacy for P is based on set of reasons R,

and either: - S abstains from claiming reasons R to be infallible,

or - S abstains from holding that reasons R necessarily, strictly, and uniquely entail policy P.

A Basic Definition of Dialogical Responsiveness

An Example:

Let S be Sam, who advocates on specific biblical reasons (R) that abortion ought to be illegal (P). Sam's advocacy for his position is dialogically responsive if and only if either:

Alternative A1--he does not hold his biblical reasons to be infallible

OR

Alternative A2--he does not hold that his biblical reasons necessarily and strictly entail his position on abortion such that his position is the only possibly acceptable social outcome on the matter

OR

Alternative A3—the conjunction of A1 & A2 is true of him.

If A1 holds of Sam:

- Sam holds his religious reasons R in a spirit of fallibility that makes them open to rational challenge and inquiry in open public discourse.

- Sam’s view would be dialogically responsive.

- Sam's rhetorical challenge in terms of logos would be mitigated.

If A2 holds of Sam:

- Sam holds R to be the infallible deliverances of an infallible being, but remains fallible with respect to his interpretation of those deliverances and what they entail about human conduct.

- At least some room remains for Sam’s interlocutors to dialogue with him about his reasons.

- Challenges to Sam's ethos are mitigated.

If A3 holds of Sam:

- Sam neither holds his religious beliefs to be infallible, nor does he suppose his preferred policy to be the only way of realizing them.

- We should take Sam to lunch for being such a swell guy.

The Takeaway

What is problematic about some some religious views in politics is the dialogically unresponsive manner in which those views tend to be held, not that they are religious as such.

Thank You!

PR-CV-DR

By Steven Patterson

PR-CV-DR

Presentation to the Marygrove College Academic Symposium, March 2015

- 396