Behavioral Incentive Compatibility

David Danz

Lise Vesterlund

Alistair Wilson

Exeter, April 2023

Incentive Compatible Mechanisms

How should we pay?

- Ask

- Ask + Pay

- Ask + Pay + Incentive compatible

Experimental economists are often faced with a choice over how to elicit information

Incentive Compatibility

- For each type there is a different uniquely maximizing choice within the mechanism

- This yields fully separating behavior

- Given this one-to-one correspondence, the analyst can interpret the relevant choice as the type

- Elicitation mechanisms are at the sharp end of mechanism design, using the above correspondence for measurement

- Often as an input into inferential regressions

- Subjective beliefs are a clear example, and are often central for inference

Behavioral Incentive Compatibility

- Need to examine the extent to which the theoretical assumptions holds

- Show that a prominent mechanism with relatively weak theoretic conditions for IC is not behaviorally incentive compatible

- Demonstrate the substantive effects of this failure over: Objective probabilities, Objective posteriors, Subjective beliefs

- Use this to motivate two methodological checks to assess Behavioral Incentive Compatibility

Example of Beliefs in Inference:

Niederle & Vesterlund (QJE 2006)

Main Idea:

Paper examines gender & competition:

- Do women compete less than men?

- Use a clever experimental design to examine tournament entry

- Measure beliefs with a very simple elicitation.

Example of Beliefs in Inference:

Niederle & Vesterlund (QJE 2006)

Use of Beliefs:

Use beliefs in two ways:

- As a left-hand-side variable to examine confidence differences between men and women

- As a right-hand-side variable to assess the degree that confidence differences explain gender differences in competition choices

Evolution of Belief Elicitation

- Niederle & Vesterlund used a very simple (and coarse) elicitation device:

- Modal rank in tournament (paying $1 if correct)

- But the literature has increasingly focused on elicitations of arbitrarily precise probabilities

- Initial IC elicitations assumed risk-neutral EU maximizers: Quadratic Scoring Rule (QSR)

- But risk aversion pushes beliefs to center

- One response to this was to control for risk preferences within the elicitation

- Another was to use an elicitation that is IC for a wider set of preferences

-

Houssain & Okui (2013): the Binarized Scoring Rule

-

Belief elicitation in practice:

-

Incentive compatibly. QSR (Brier, 1950), BSR (Roth and Malouf, 1979; Grether, 1980; Allen, 1987; Hossain and Okui, 2013; Schlag and van der Weele, 2013), BDM (Holt and Smith, 2009; Karni, 2009)

-

Surveys (Manski, 2004; Schotter and Trevino, 2014; Schlag et al., 2015)

-

Distortions and corrections (Offerman et al., 2009, Andersen et al., 2013; Harrison et al., 2013; Armantier and Treich, 2013; Schlag and van der Weele, 2013)

-

Stakes and hedging (Blanco et al., 2010; Coutts, 2019)

-

Does elicitation change behavior? (Croson, 2000; Wilcox and Feltovich, 2000; Rutstrom and Wilcox, 2009; Gächter and Renner, 2010)

Belief elicitation in practice:

- Does incentivization matter? (Offerman and Sonnemans, 2004; Gächter and Renner, 2010; Wang, 2011; Trautmann and van de Kuilen, 2014)

-

Does properness matter? (Nelson and Bessler, 1989; Palfrey and Wang, 2009)

-

Consistency with actions (Cheung and Friedman, 1995; Nyarko and Schotter, 2001; Costa-Gomes and Weizsäcker, 2008; Rey-Biel, 2009; Blanco et al., 2011; Ivanov, 2011; Hyndman et al., 2013; Armantier et al., 2013)

-

Models of belief formation (Fudenberg and Levine, 1998; Camerer and Ho, 1999; Nyarko and Schotter, 2001; Hyndman et al., 2012)

-

Bayesian updating (Holt and Smith, 2009; Benjamin, 2019)

-

Higher-order beliefs (Dufwenberg and Gneezy, 2000; Charness and Dufwenberg, 2006; Manski and Neri, 2013)

Binarized scoring rule (Hossain and Okui, 2013)

- Each reported belief q is linked to state-contingent lottery.

- With a binary outcome:

BSR – Binarized scoring rule

- BSR the state-of-the-art in belief elicitation

- Superior theoretical properties: Incentive compatible for individuals aiming to maximize the chance of winning a prize

- Superior performance: Outperforms the standard (non-binarized) quadratic scoring rule (Hossain and Okui, 2013; Harrison and Phillips, 2014)

- Investment and portfolio choice (Hillenbrand and Schmelzer, 2017; Drerup et al., 2017)

- Coordination (Masiliūnas, 2017)

- Matching markets (Chen and He, 2017; Dargnies et al., 2019)

- Biased information processing (Hossain and Okui, 2019; Erkal et al., 2019)

- Cheap talk (Meloso et al., 2018)

- Risk taking (Ahrens and Bosch-Rosa, 2018)

- Information source choice (Charness, Oprea, and Yuksel, forthcoming)

- Memory and uncertainty ( Enke, Schwerter, and Zimmermann, 2020; Enke and Graeber, 2019)

- Discrimination (Dianat, Echenique, and Yariv, 2018)

- Gender and coordination (Babcock et al., 2017)

- Correlated and motivated beliefs (Oprea and Yuksel, 2020; Cason, Sharma, and Vadovič, 2020)

Task

Each belief scenario consists of three seperate elicitations.

- Guess 1: Prior

- Guess 2: Posterior

- Guess 3: Posterior

Initial Design

- 5 treatments

- Treatment variation: Information on incentives

- Holding constant across treatments

- Incentives

- Experimental procedures

- All scenarios and random draws matched

- 60 participants per treatment (3x20)

- Written instructions read out loud, slide summary

- 10 scenarios with random draws (30 elicitations total)

- Payment

- $8 show up

- $8 prize with one guess paid from two scenarios

- One participant per session paid for end-of-experiment elicitations

Baseline: Information Treatment

| Property | Information |

|---|---|

| Dominant Strategy | |

| Payoff Description | |

| Payoff Slider | |

| Feedback |

✅

✅

✅

✅

✅

✅

✅

✅

Dominant Strategy

Instructions:

The payment rule is designed so that you can secure the largest chance of winning the prize by reporting your most-accurate guess.

Slide summarizing instructions:

(literally the last thing they see

before they begin making decisions)

Payoff Description

- Randomly draw two uniform numbers between 0-100

- If the selected urn is the Red urn: You will win the $8 prize if Your Guess is greater than or equal to either of the two Computer Numbers.

- If the selected urn is the Blue urn: You will win the $8 prize if Your Guess is less than either of the two Computer Numbers.

- Yields the BSR lottery probabilities (Wilson & Vespa 2018)

Payoff Slider

Feedback

At the end of each round:

- Realized urn

- Earned probability on each elicitation

Results

-

Prior (Guess 1)

-

Posteriors (Guesses 2&3)

Guess 1: Prior Elicitation

Should report induced prior if incentivized to tell truth

Only 15 percent of participants consistently report given prior

Information: False priors report

What Drives False Reports?

-

Confusion (inability/unwillingness to report given prior)

-

Incentives:

-

Failure to reduce compound lottery (RCL)

-

Payoff structure

-

BSR Payoffs

- Reporting a belief toward center

- large increase in chance of winning on unlikely event

- smaller decrease in chance of winning on likely event

84% chance

83% chance

- Cheap false reports:

- 10% pt deviation from truth reduces chance of winning by 1% pt

| Stated Belief on Red | Chance to Win if Red | Chance to Win if Blue |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100% | 0% |

| 0.9 | 99% | 19% |

| 0.8 | 96% | 36% |

| 0.7 | 91% | 51% |

| 0.6 | 84% | 64% |

| 0.5 | 75% | 75% |

What Drives False Reports?

-

Confusion (inability/unwillingness to report given prior)

-

Incentives:

-

Failure to reduce compound lottery (RCL)

-

Payoff structure (asymmetric and flat incentives)

-

Evidence that Incentives drive False Reports

- False reports more likely on non-centered than centered priors

- Deviations more likely toward center than near extreme (reports pull-to-center)

Elicited Priors at 0.3

Near-extreme

Center

Distant-extreme

False-report movements

Proportion of non-centered reports in each bin:

Evidence of incentives distorting reports

- False reports more likely on non-centered than centered priors

- Pull-to-center: Deviations more likely toward center than near extreme

- Survey responses discuss a hedging motive

- Confusion

-

Incentives

-

Failure to reduce compound lottery

-

flatness

-

asymmetry

-

-

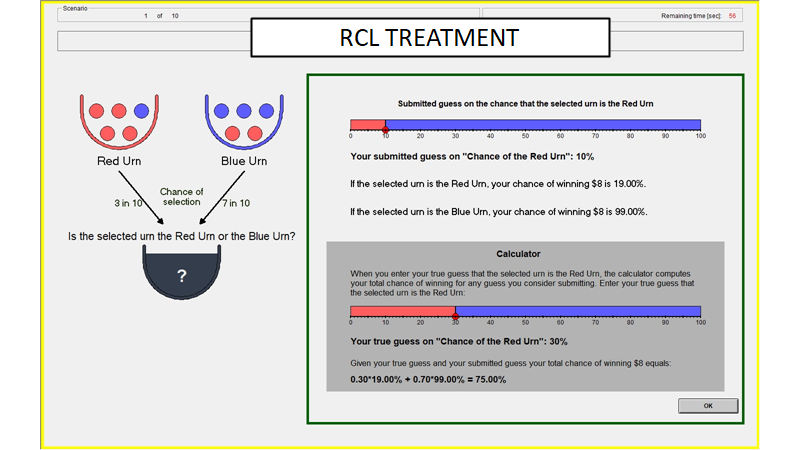

Vary information on incentives:

-

RCL-calculator : Aid reduction of compound lottery

-

No-Information: Eliminate quantitative information on incentives

-

Cause of false BSR reports?

✅

✅

✅

✅

❌

✅

✅

✅

✅

❌

Treatments:

- RCL adds information on the incentives

- No Information subtracts information

| Property | Information | RCL | No-Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant Strategy | | ||

| Payoff Description | | ||

| Payoff Slider | | ||

| Feedback | | ||

| RCL calculator | |

✅

❌

❌

❌

❌

✅

✅

✅

✅

✅

Information treatment

RCL Treatment

No Information treatment

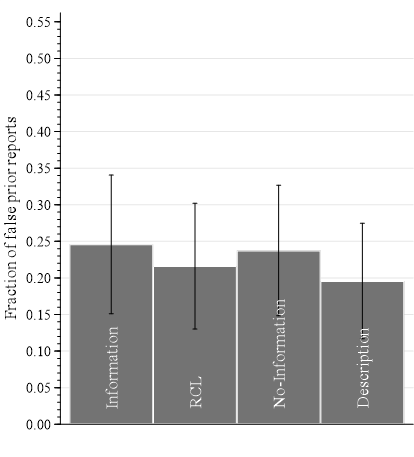

What drives BSR false reports?

| Treatment | Source |

|---|---|

| Information | confusion, BSR incentives, failed RCL |

| RCL | confusion, BSR incentives |

| No Information | confusion |

False Reports by Round

Truthful reporting greatest w/o incentive information

False reports by Prior

Near-extreme

Center

Distant-extreme

Proportion of non-centered reports in each bin:

Inf:

RCL:

NoInf:

Distribution of false reports

By prior location:

Confusion

BSR Incentives

Compounding

False reports

Centered Prior

BSR Incentives

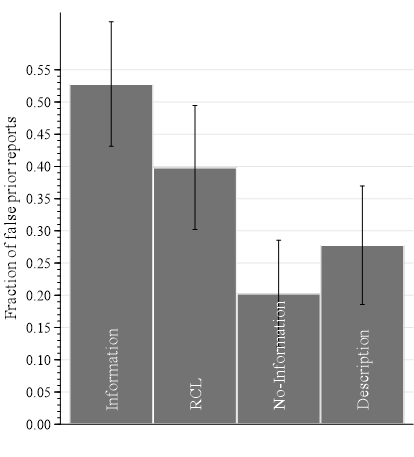

- Information on BSR incentives increases false reports (by 150%) (between-subject)

- Test effect of information within subject

- Feedback Treatment

- No-Info + scenario feedback with gradual information on incentives

- Feedback Treatment

| Property | Inf | RCL | No-Inf | Feedback |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant Strategy | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Payoff Description | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Payoff Slider | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Feedback | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

| RCL calculator | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

Feedback Treatment

Feedback screen

False prior reports

- Starts out at No Information level

- Ends up at Information level

- Information on incentives distorts truthful reporting within subject

False Reports of Prior

Summary so far...

-

Information on incentives increases false reports

-

Between subject: Information vs. No-Information

-

Within subject: Feedback

-

-

What is ‘enough’ information to maintain truth telling?

-

Description Treatment

-

| Property | Inf | RCL | No-Inf | Feedback | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant Strategy | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Payoff Description | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Payoff Slider | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Feedback | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ |

| RCL calculator | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

Description Treatment

Description Treatment

By round

By prior

False Reports

Summary

- Evidence for systematic distortions over objective priors

- When subjects are informed on the incentives they make systematic deviations

- That deviations are purposeful distortions is clearest

- But the environment is perhaps more artificial

- The same patterns are observed over Bayesian Posteriors

- Data here is harder to pinpoint as we don't know the 'true' posterior beliefs

- But distributions of response shift in same systematic way

- Two questions raised:

- Would this also hold for subjective beliefs?

- Does any of this matter for inference?

BSR Usage in Literature

- Most papers are eliciting probabilistic beliefs

- Most papers give two or more quantitative examples of the incentives

- Usage for beliefs is both as a LHS and RHS variable

EU assumption is used at observation level!

- EU in standard economic theory is typically used at an aggregate (i.e. average) level

- Predict a comparative static for a population

- But in the elicitation EU is used at the observation level:

- Use the IC under EU to interpret a choice over incentives as a measured belief

- 'Small' mistakes in the EU assumption can lead to a measurement error for any inference

- Regressions using mismeasured data can cause biased inference

Inferential Effects

To understand the effects on inference we use a simple model of the center-bias distortions

Observed belief is:

Regression model where X is a binary treatment indicator:

What happens when distorted beliefs are used?

Inferential Effects

Observed belief is:

Left-hand-side effect is clear:

- Mismeasurement of q leads to an attenuation of the estimated treatment effect

Inferential Effects

Observed belief is:

Right-hand-side treatment effect will depend on unknowns:

Niederle & Vesterlund (2006)

We return to the Niederle & Vesterlund study:

- Perform sums for a piece rate

- Perform sums in tournament

- Choose the preferred incentive

- Elicit subjective belief

- (here using BSR)

Run this study twice:

- NV-Information: Quantitative information

- NV-No-Information : No precise information

LHS: Confidence difference between men and women:

RHS: Competition difference for men and women after controlling for confidence:

NV Inference equations

Information predicted to attenuate gender confidence difference

Information predicted to make the gender-gap in tournament-entry larger (after controlling for confidence

Elicited Beliefs

NV-No-Information

NV-Information

Elicited Beliefs

NV-No-Information

NV-Information

NV-Regressions LHS

Original finding is that:

- Women are less confident over their performance than men

- Prediction from model for NV-Information is that gender gap will move towards zero.

NV-Regressions RHS

- Original finding is that:

- Beliefs explain a significant proportion of the gender gap

- Prediction from model for NV-Information is that gender gap in competition is more negative:

- (gender gap in confidence)

- (Belief effect on entry)

NV Replication Results

- NV-Information distorts beliefs to center, relative to NV-No-Information

- This difference in the beliefs affects final inference:

- As a LHS variable it attenuates the treatment effect (here a gender gap over beliefs)

- As a RHS variable it widens the measured gender gap over competition after controlling for beliefs

- So, simply by providing the participants with information on the elicitation incentives, that we can qualitatively distort the subsequent inference

Going Forward...

- The BSR does not work as an incentive-compatible elicitation

- The less you tell the participants about the incentives, the worse the data

- This is true for:

- Objective priors

- Updated posteriors

- Subjective beliefs

- New elicitations are required. But how should we go about assessing them?

Propose two weak tests for behavioral incentive compatibility

- The mechanism should not yield worse data when participants are given precise information on the incentives on offer

- If presented with the pure incentives available in the mechanism, the majority of participants should be choosing the theorized maximizer

Weak Condition 1:

BIC Diagnostic 1:

- Information vs No Information comparison

Our paper demonstrates this methodology across:

- Elicitation of an objective prior

- Elicitation of an objective posterior

- Elicitation of a subjective belief

Have similar data showing this comparison for:

- Quadratic scoring rule

- Binarized-BDM

Weak Condition 2:

BIC Diagnostic 2:

- Extract the pure incentives from the elicitation and ask the participants to choose. A majority should be choosing the theorized maximizer

| Lottery pair | Red lottery ticket | Blue lottery ticket |

|---|---|---|

| A (0%) | 100% | 0% |

| B (10%) | 99% | 19% |

| C (20%) | 96% | 36% |

| D (30%) | 91% | 51% |

| E (40%) | 84% | 64% |

| F (50%) | 75% | 75% |

| G (60%) | 64% | 84% |

| H (70%) | 51% | 91% |

| I (80%) | 36% | 96% |

| J (90%) | 19% | 99% |

| K (100%) | 0% | 100% |

Fix the probability of Red and ask for a choice from:

Weak Condition 2:

We asked 120 subjects to choose their preferred lottery pair when the probability of Red was set to either 20% or 30%. Interpret choice via the EU assumption:

Weak Condition 2:

Same thing, but for QSR incentives:

Weak Condition 2:

Same thing, but for binarized-BDM (Karni)

Weak Condition 2:

First Price Auction, two bidders, uniform values:

v⋆=0.3

| Lottery pair | Prize | Probability |

|---|---|---|

| A (v=0.0) | $12 | 0% |

| B (v=0.1) | $10 | 10% |

| C (v=0.2) | $8 | 20% |

| D (v=0.3) | $6 | 30% |

| E (v=0.4) | $4 | 40% |

| F (v=0.5) | $2 | 50% |

| G (v=0.6) | $0 | 60% |

| H (v=0.7) | -$2 | 70% |

| I (v=0.8) | -$4 | 80% |

| J (v=0.9) | -$6 | 90% |

| K (v=1.0) | -$8 | 100% |

Weak Condition 2:

First Price Auction, two bidders, uniform values:

v⋆=0.7

| Lottery pair | Prize | Probability |

|---|---|---|

| A (v=0.0) | $28 | 0% |

| B (v=0.1) | $26 | 10% |

| C (v=0.2) | $24 | 20% |

| D (v=0.3) | $22 | 30% |

| E (v=0.4) | $20 | 40% |

| F (v=0.5) | $18 | 50% |

| G (v=0.6) | $16 | 60% |

| H (v=0.7) | $14 | 70% |

| I (v=0.8) | $12 | 80% |

| J (v=0.9) | $10 | 90% |

| K (v=1.0) | $8 | 100% |

Weak Condition 2:

v⋆=0.3

v⋆=0.7

First Price Auction:

Weak Condition 2:

Uniform Preferences

Correlated Preferences

Deferred Acceptance (Proposing over $6/$4/$2)

Assume all other players truthfully reveal

- Two other proposers

- Three prize amounts

Weak Condition 2:

Uniform Preferences

Deferred Acceptance (Proposing over $6/$4/$2)

| Lottery pair | $8 | $6 | $2 | $0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (6>8>2) | 26% | 64% | 10% | 0% |

| B (6>8>2) | 26% | 64% | 0% | 10% |

| C (6>2>8) | 10% | 64% | 26% | 0% |

| D (6>2) | 0% | 64% | 26% | 10% |

| E (8>6>2) | 64% | 26% | 10% | 0% |

| F (8>6) | 64% | 26% | 0% | 10% |

| G (8>2>6) | 64% | 10% | 26% | 0% |

| H (8>2) | 64% | 0% | 26% | 10% |

| I (2>6>8) | 10% | 26% | 64% | 0% |

| J (2>6) | 0% | 26% | 64% | 10% |

| K (2>8>6) | 26% | 10% | 64% | 0% |

| L (2>8) | 26% | 0% | 64% | 10% |

Weak Condition 2:

Correlated Preferences

Deferred Acceptance (Proposing over $6/$4/$2)

| Lottery pair | $8 | $6 | $2 | $0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (6>8>2) | 9% | 64% | 29% | 0% |

| B (6>8) | 9% | 64% | 0% | 29% |

| C (6>2>8) | 1% | 64% | 36% | 0% |

| D (6>2) | 0% | 64% | 36% | 1% |

| E (8>6>2) | 41% | 33% | 26% | 0% |

| F (8>6) | 41% | 33% | 0% | 26% |

| G (8>2>6) | 41% | 7% | 52% | % |

| H (8>2) | 47% | 0% | 52% | 7% |

| I (2>6>8) | 1% | 8% | 91% | 0% |

| J (2>6) | 0% | 8% | 91% | 1% |

| K (2>8>6) | 2% | 7% | 91% | 0% |

| L (2>8) | 2% | 0% | 91% | 7% |

Weak Condition 2:

Uniform Preferences

Correlated Preferences

Deferred Acceptance (Proposing over $6/$4/$2)

Conclusions

- On the Binarized Scoring Rule

- Substantial false-report rate for objective prior

- Systematic deviations driven by information on the incentives

- Between (Information vs No Information)

- Within (gradual Feedback)

-

Distortions generated can qualitatively affect inference

-

Replication of Niederle & Vesterlund fails when incentive information present

-

Conclusion

- Overly content to appeal to theoretical incentive compatibility, when what is actually required are notions of behavioral compatibility

- For belief elicitation, qualitative notions are effective:

- Both No Information and Description work well

- But need to ask ourselves if it truly the incentives, instead of framing/call to authority

- Might want to ask if it even makes sense to collect arbitrarily precise beliefs.

- Methodology offers simply diagnostic checks for behavioral incentive compatibility

- Simple demonstrations for check on First Price auctions and Matching mechanisms

B-IC (Exter)

By Alistair Wilson

B-IC (Exter)

- 30