Competitive Equilibrium with Production and Trade

Christopher Makler

Stanford University Department of Economics

(or, Econ 50: Lecture 32)

Econ 51: Lecture 6

pollev.com/chrismakler

Will you need a left-handed desk for exams?

Today's Agenda

- Model 1: Alison and Bob (curved PPFs)

- Incomplete specialization

- Smooth supply and demand curves

- Model 2: Chuck and Wilson (linear PPFs)

- Complete specialization

- Comparative advantage and gains from trade

- Review

You might feel a little like this

by the end of the lecture today.

Don't worry, this is a perfectly natural reaction.

Breathe slowly and deeply, and focus on the economics.

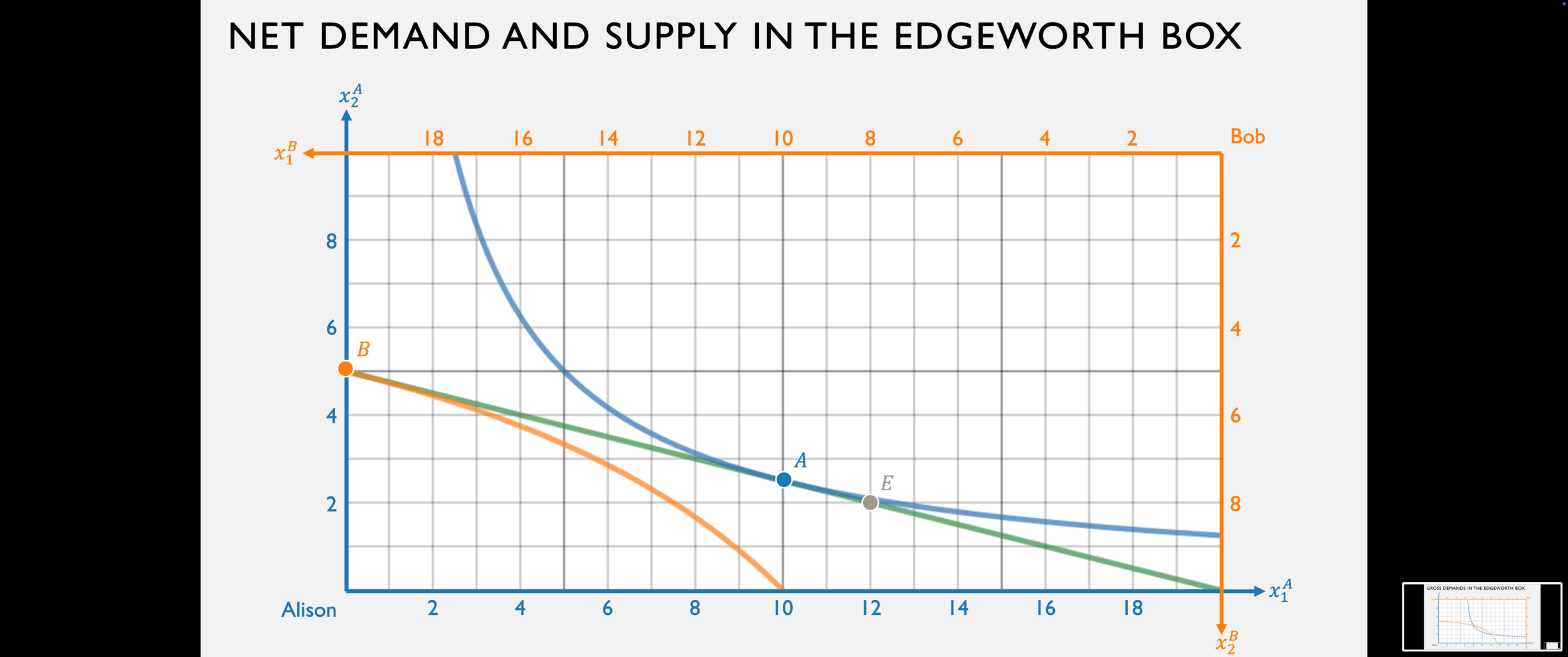

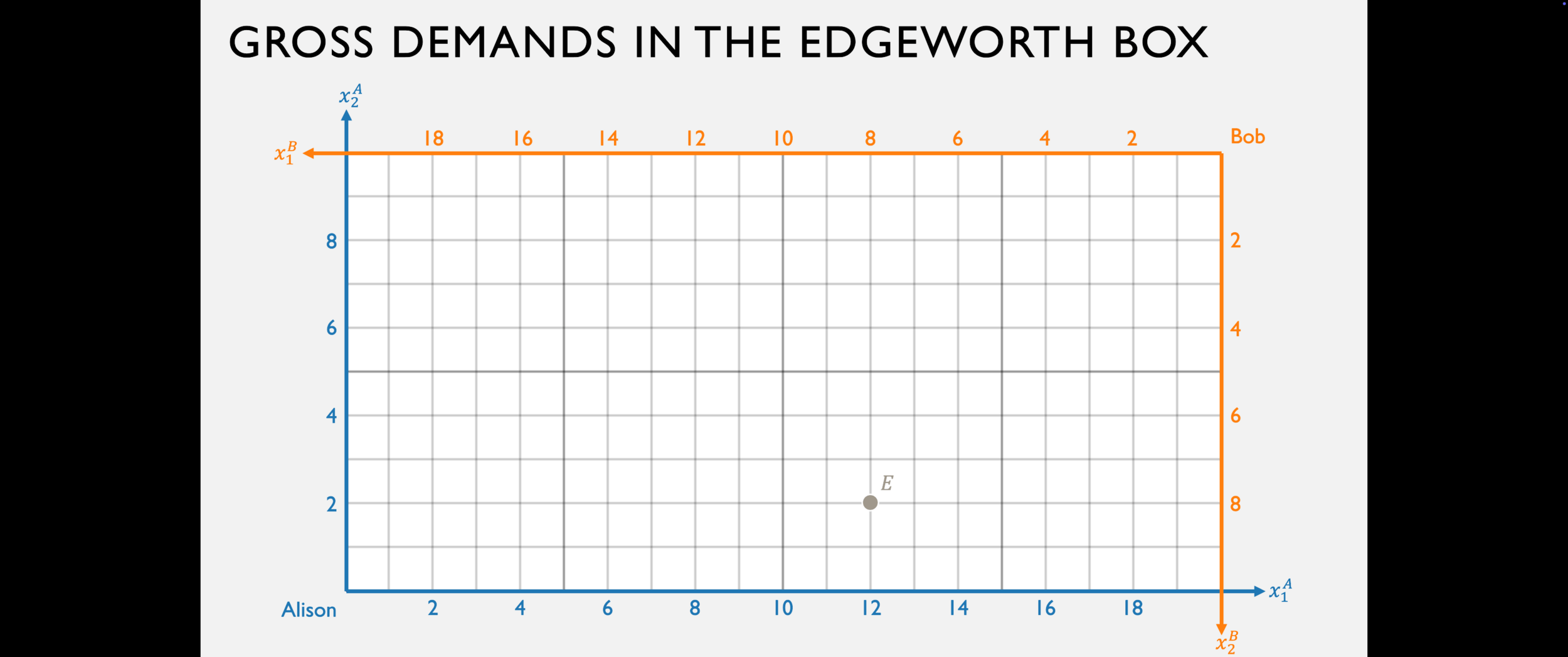

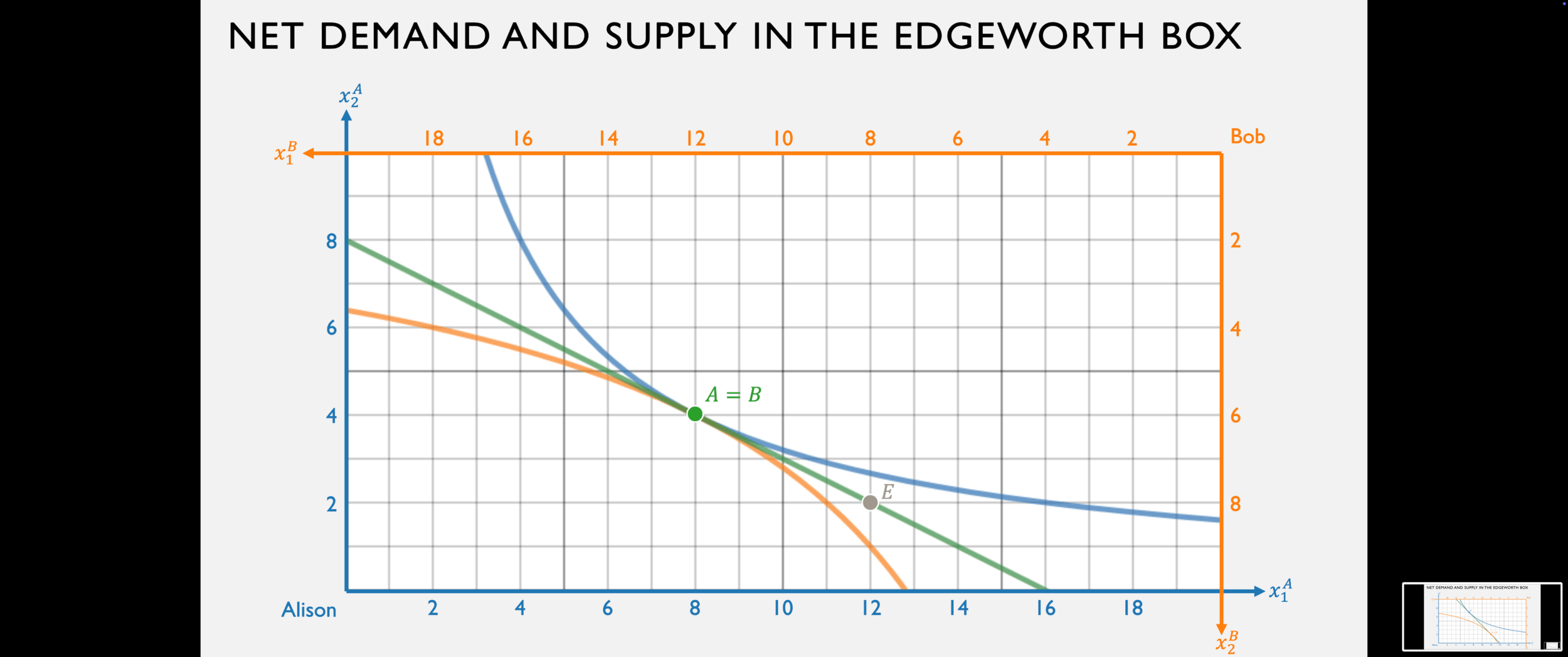

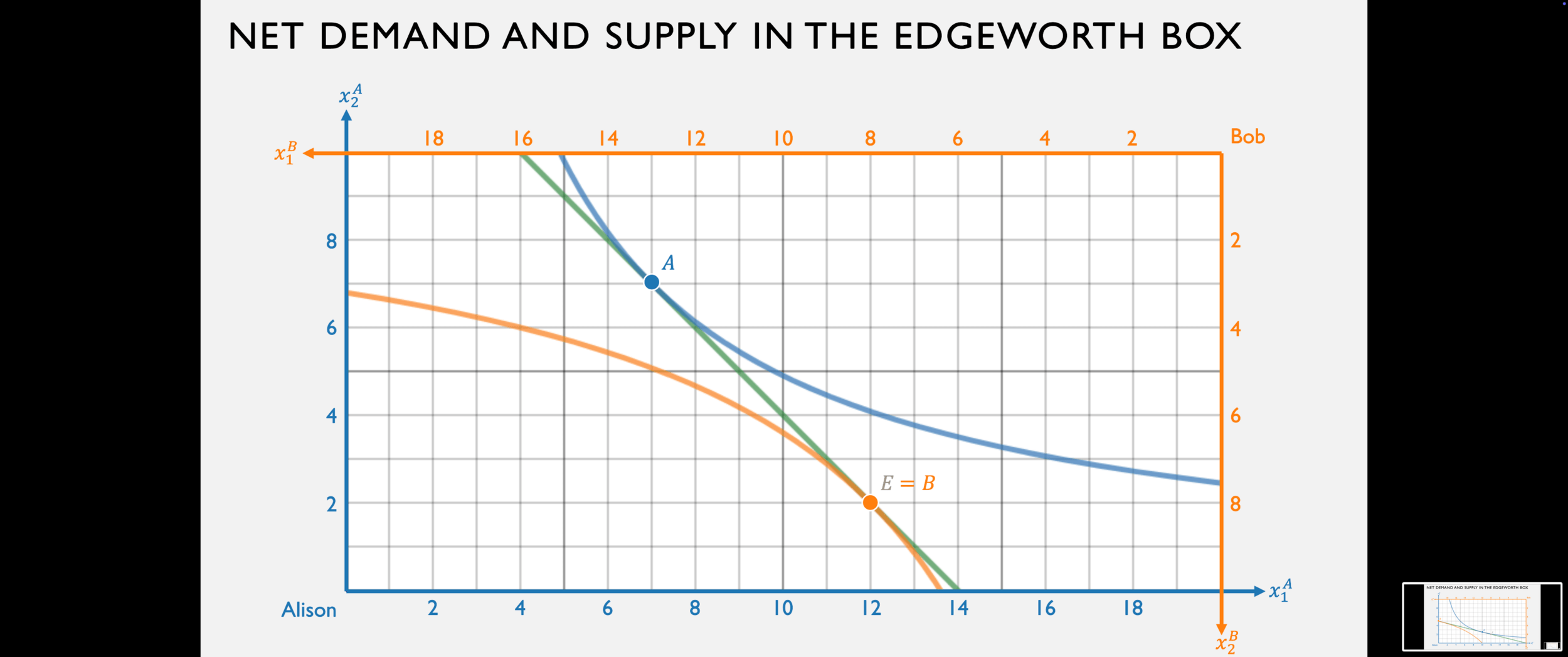

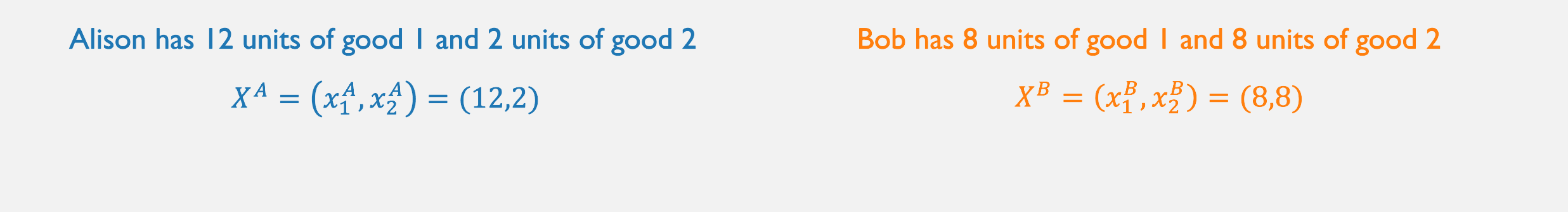

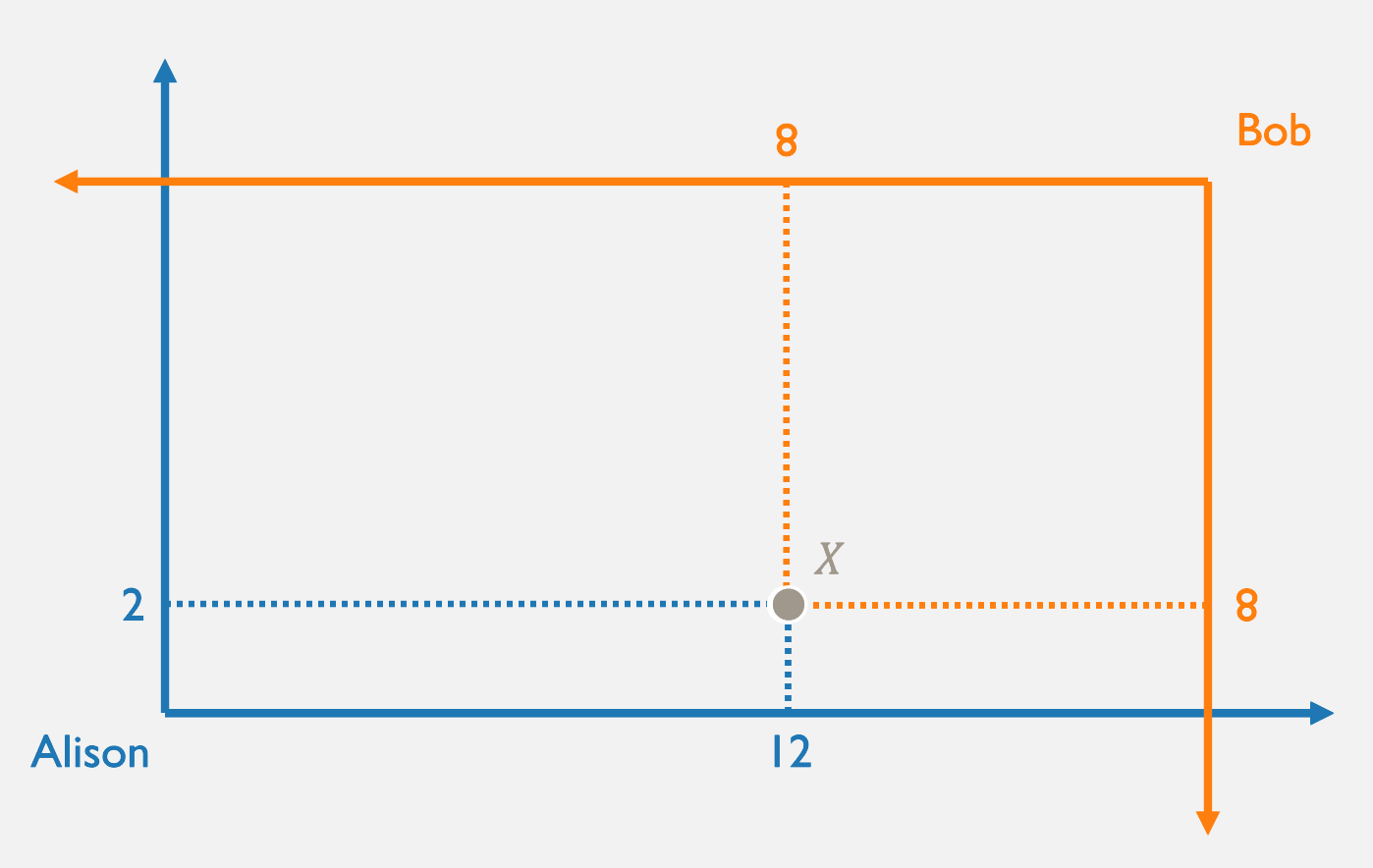

Alison and Bob

Bob's gross demand for good 1 is:

Alison's gross demand for good 1 is:

His net demand for good 1 is:

Her net supply of good 1 is:

Bob demands 12

Alison supplies 2

Bob's gross demand for good 1 is:

Alison's gross demand for good 1 is:

His net demand for good 1 is:

Her net supply of good 1 is:

Bob demands 4

Alison supplies 4

Bob's gross demand for good 1 is:

Alison's gross demand for good 1 is:

His net demand for good 1 is:

Her net supply of good 1 is:

(Bob demands 0)

Alison supplies 5

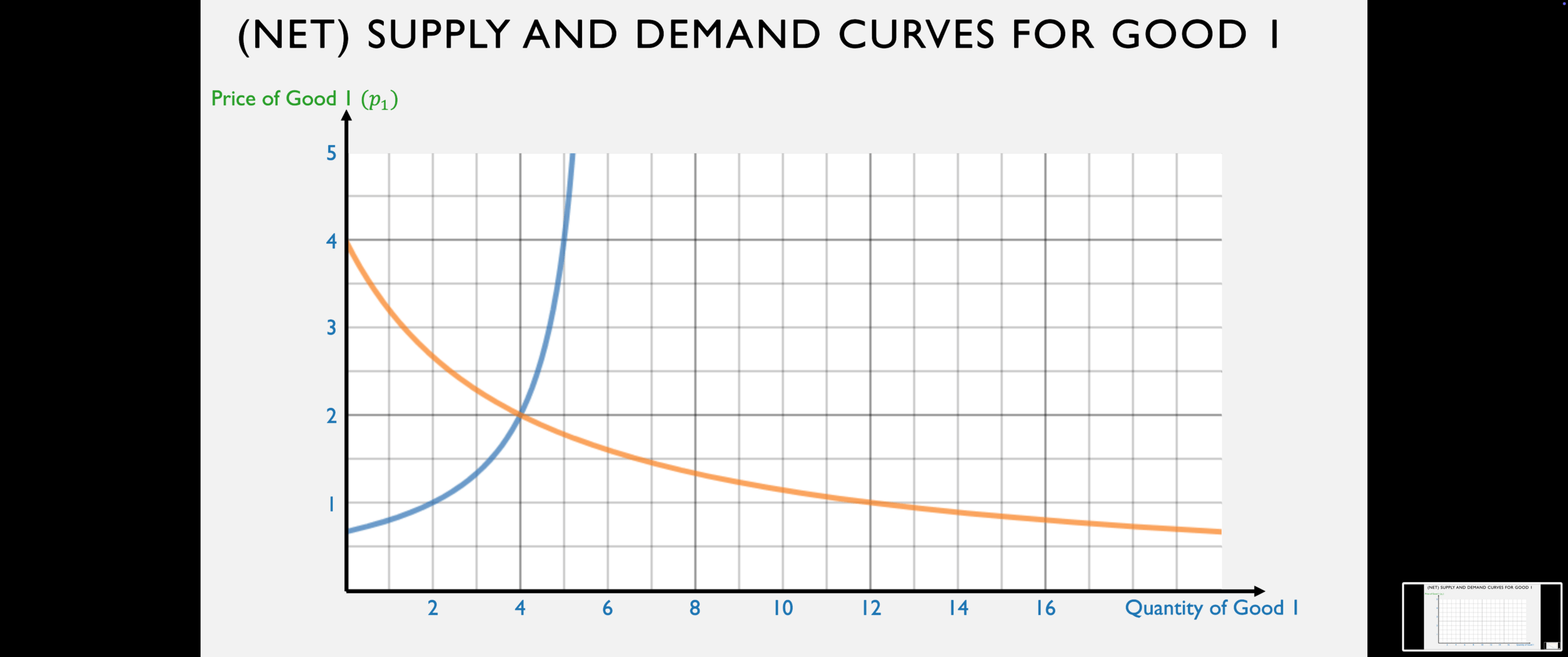

Bob's net demand for good 1 is:

Alison's net supply of good 1 is:

....but where did this "endowment" come from?

We've been starting with an ‟endowment" of goods...

Step 1: Supply

Joint PPFs with Diminishing MPL

Alison

Bob

Optimal Choice with Prices

Now suppose Chuck can buy and sell these goods at prices \(p_1\) and \(p_2\).

Money from spending

another hour producing fish

Money from spending

another hour

producing coconuts

At each price of good 1, we can say how much good 1 each will supply at that price

At each price of good 1, we can say how much good 1 each will supply at that price

Step 2: Demand

Alison's supply decision (which becomes her endowment)

Monetary value of the bundle Alison produces

Alison's supply decision (which becomes her endowment)

Monetary value of the bundle Alison produces

Alison's demand for good 1 (if \(u^A(x_1,x_2) = x_1x_2\))

Step 3: Equilibrium

Given any price ratio, Alison and Bob will choose some amounts to produce; this determines the dimensions of the Edgeworth Box, as well as their endowment in it.

They will then choose how much they want to sell of the goods they produced, in order to buy the other good from the other person, at that price ratio.

Competitive equilibrium occurs at the price ratio for which they end up wanting to trade to the same bundle.

Chuck and Wilson

Optimization in Autarky

Marginal Rate of Transformation (MRT)

- The number of coconuts you need to give up in order to get another fish

- Opportunity cost of fish in terms of coconuts

Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS)

- The number of coconuts you are willing to give up in order to get another fish

- Willingness to "pay" for fish in terms of coconuts

Both of these are measured in

coconuts per fish

(units of good 2/units of good 1)

Marginal Rate of Transformation (MRT)

- The number of coconuts you need to give up in order to get another fish

- Opportunity cost of fish in terms of coconuts

Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS)

- The number of coconuts you are willing to give up in order to get another fish

- Willingness to "pay" for fish in terms of coconuts

Opportunity cost of marginal fish produced is less than the number of coconuts

you'd be willing to "pay" for a fish.

Opportunity cost of marginal fish produced is more than the number of coconuts

you'd be willing to "pay" for a fish.

Better to spend less time fishing

and more time making coconuts.

Better to spend more time fishing

and less time collecting coconuts.

Utility of spending

another hour producing fish

Utility value of spending

another hour producing coconuts

Optimize by setting them equal to one another

Optimize by setting them equal to one another

For a Cobb-Douglas utility function of the form

The “Cobb-Douglas Rule" for Production

the producer/consumer will optimally spend fraction \(a/(a+b)\) of their total resource value on good 1, and fraction \(b/(a+b)\) on good 2.

Example: Chuck has 12 hours of labor, and can produce 2 coconuts per hour or 1 fish per hour.

His preferences may be represented by the utility function \(u(x_1,x_2) = x_1x_2^2\)

What does the Cobb-Douglas rule say he should do?

Specialization and Trade

Now suppose Chuck can buy and sell these goods at prices \(p_1\) and \(p_2\).

Notation: \(y_i\) is the amount he produces of good \(i\); \(x_i\) is the amount he consumes.

Money from spending

another hour producing fish

Money from spending

another hour

producing coconuts

With linear production functions, he should completely specialize in one or the other!

Two Agents

Solving for Equilibrium I: Production

We know that Chuck and Wilson have different opportunity costs of producing fish:

CHUCK

WILSON

For what range of price ratios will each of them specialize in the good for which they have a comparative advantage?

Solving for Equilibrium II: Trade

Once everyone is specializing, we have the endowments:

CHUCK

WILSON

How much fish will each supply and demand at different prices?

Suppose both Chuck and Wilson have

Cobb-Douglas preferences given by

CHUCK

WILSON

Let's fix \(p_2 = 1\) and solve for \(p_1\).

VALUE OF ENDOWMENT

OPTIMAL CHOICE

SUPPLY AND DEMAND

What have we learned?

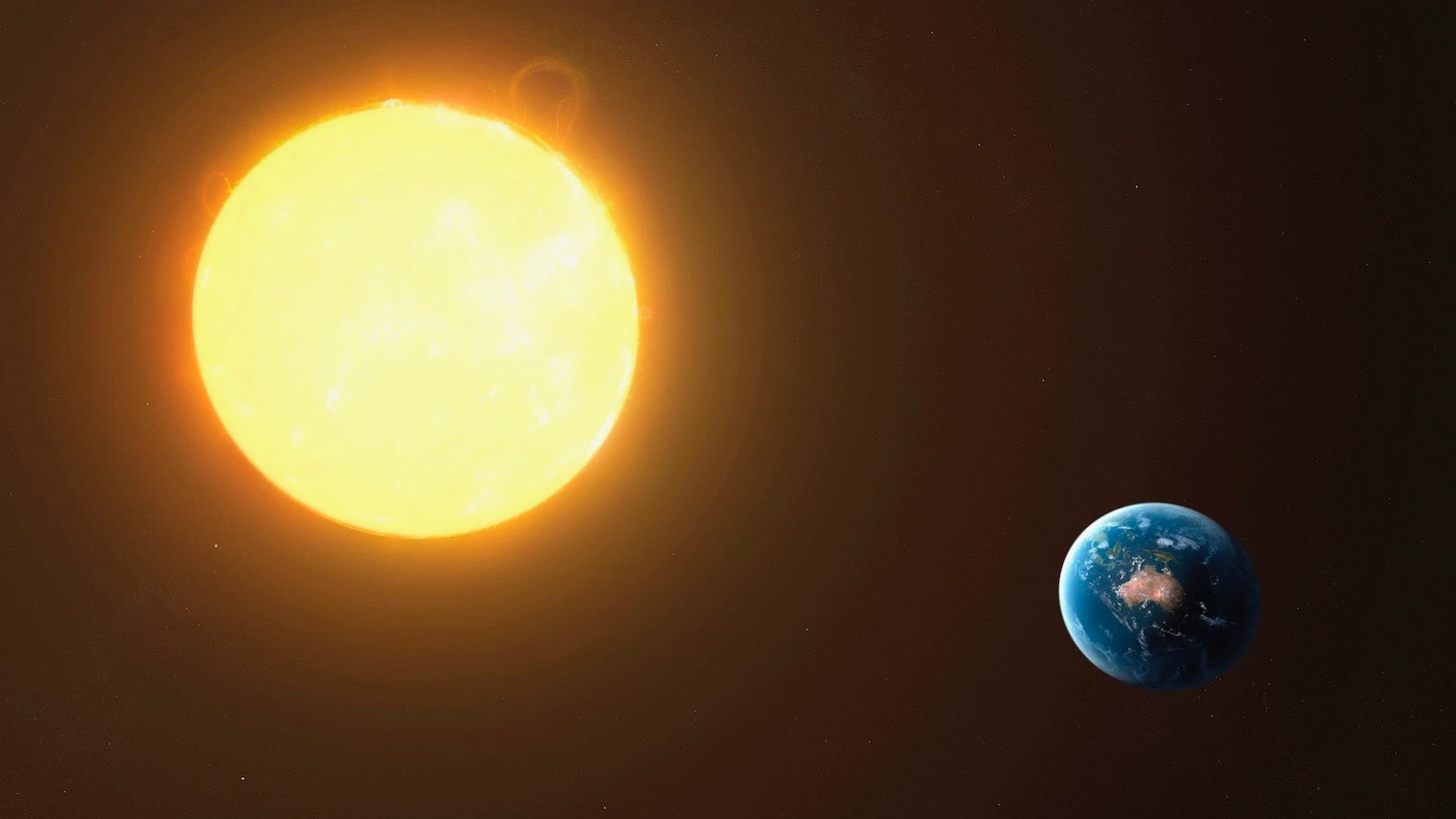

Far out in the uncharted backwaters of the unfashionable end of the western spiral arm of the Galaxy lies a small unregarded yellow sun.

SCIEPRO/GETTY IMAGES

Orbiting this at a distance of roughly ninety-two million miles is an utterly insignificant little blue green planet whose ape-descended life forms are so amazingly primitive that they still think digital watches are a pretty neat idea.

This planet has — or rather had —

a problem, which was this:

😢

most of the people on it were unhappy for pretty much of the time.

Many solutions were proposed

for this problem...

...but most of these were largely concerned with the movements

of small green pieces of paper,

which is odd because on the whole

it wasn't the small green pieces of paper that were unhappy.

Resources

Technology

Stuff

Happiness

🌎

🏭

⌚️

🤓

The Real World

Demand

Supply

Equilibrium

🤩

🏪

⚖

Little Green

Pieces of Paper

Resources

Technology

Stuff

Happiness

🌎

🏭

⌚️

🤓

The Real World

Little Green

Pieces of Paper

- A change in the price of a good results in a movement along its demand curve

- A change in income or the price of other goods results in a shift of the demand curve

TR

TC

MR

MC

Take derivative and set = 0:

Solve for \(q^*\):

SUPPLY FUNCTION

"Keep producing output as long as the marginal revenue from the last unit produced is at least as great as the marginal cost of producing it."

"Keep hiring workers as long as the marginal revenue from the output of the last worker is at least as great as the cost of hiring them."

Profit as a function of output \(q\)

Profit as a function of labor \(L\)

So...how do firms choose a point along the PPF?

Consider a PPF with "guns" (military goods) and "butter" (civilian goods)

An international conflict increases the demand for guns. What effect does this have on the market for butter?

Step 1: The increased demand for guns raises the price of guns, thereby increasing the demand for labor by gun firms at every wage:

So, let's put this all together.

The increase in demand for guns leads to an increase in overall labor demanded, which leads to an increase in the wage rate.

What effect does this have on the supply curves of guns and butter?

Conditions for

GDP Maximization

TANGENCY CONDITION

CONSTRAINT CONDITION

Firms in industry 1 set \(w = p_1 \times MP_{L1}\)

Firms in industry 2 set \(w = p_2 \times MP_{L2}\)

How does competition achieve this?

Wages adjust until the

labor market clears

General Equilibrium

The Circular Flow

In our consumer theory, we've treated income as exogenous.

In our producer theory, we've treated wages as exogenous.

We've also assumed firms are maximizing profits, but haven't said where those profits go.

Crazy thought: what if the money firms pay for labor becomes the income of workers?

...and their profits become the income of the owners/shareholders of the firm?

Consumers

Good 1 Firms

Market for Good 1

Market for Good 2

Market for Labor

Good 2 Firms

Money flows clockwise

Goods, labor flow counter-clockwise

General Equilibrium: Everyone optimizes, all markets clear simultaneously.

Competitive Equilibrium

We sometimes call the autarky model the "centralized" model: if there were a single agent making a decision, what would they do?

Similarly, we call competitive equilibrium a "decentralized" model, because lots and lots of individuals are making small decisions that add up to what "society chooses"

1. Given prices \(p_1,p_2\), firms will choose the point \((Y_1^*,Y_2^*)\) along the PPF where \(MRT = \frac{p_1}{p_2}\)

2. All money received by firms \((p_1Y_1^* + p_2Y_2^*)\) will become income \(M\) for consumers.

3. Given prices \(p_1,p_2\) and income \(M\), the consumer will choose the point \((X_1^*,X_2^*)\) along the budget line where \(MRS = \frac{p_1}{p_2}\)

4. At equilibrium prices, markets clear (\(X_1^* = Y_1^*\) and \(X_2^* = Y_2^*\)) so \(MRS = MRT\).

5. In disequilibrium, there is a shortage in one market and a surplus in the other, pulling the system toward equilibrium.

Overview of General Equilibrium

1. Given prices \(p_1,p_2\), firms will choose the point \((Y_1^*,Y_2^*)\) along the PPF where \(MRT = \frac{p_1}{p_2}\)

2. All money received by firms \((p_1Y_1^* + p_2Y_2^*)\) will become income \(M\) for consumers.

3. Given prices \(p_1,p_2\) and income \(M\), consumers will choose the point \((X_1^*,X_2^*)\) along the budget line where \(MRS = \frac{p_1}{p_2}\)

If consumers and firms all face the same price, and if they choose the same quantity in response to that price, then MRS = MRT.

The Neoclassical Model

If every decision involves setting the marginal cost of any decision equal to the marginal benefit

(or the marginal opportunity cost equal to the marginal rate of substitution), AND

if everyone bases their decisions on a common price (either for selling or buying each good), THEN

prices in perfectly competitive markets act as a coordination mechanism that equates

one person's marginal cost to another's marginal benefit

THE INVISIBLE HAND IS MAGIC

FREE MARKETS ARE EFFICIENT

There's just one tiny problem...

That's not the world we live in.

Next 7 weeks: it all falls apart.

Econ 50 | 06 | The Neoclassical Model

By Chris Makler

Econ 50 | 06 | The Neoclassical Model

General equilibrium

- 511