Competitive Equilibrium in the Edgeworth Box

Christopher Makler

Stanford University Department of Economics

Econ 51: Lecture 6

Today's Agenda

- Review of Week 1: exchange optimization; net demand and supply

- Review of last time: the Edgeworth Box framework

- Trading in the Edgeworth Box at a common price ratio

- Net demand and net supply

- Solving for the equilibrium price ratio

- Alison and Bob example

- General Cobb-Douglas

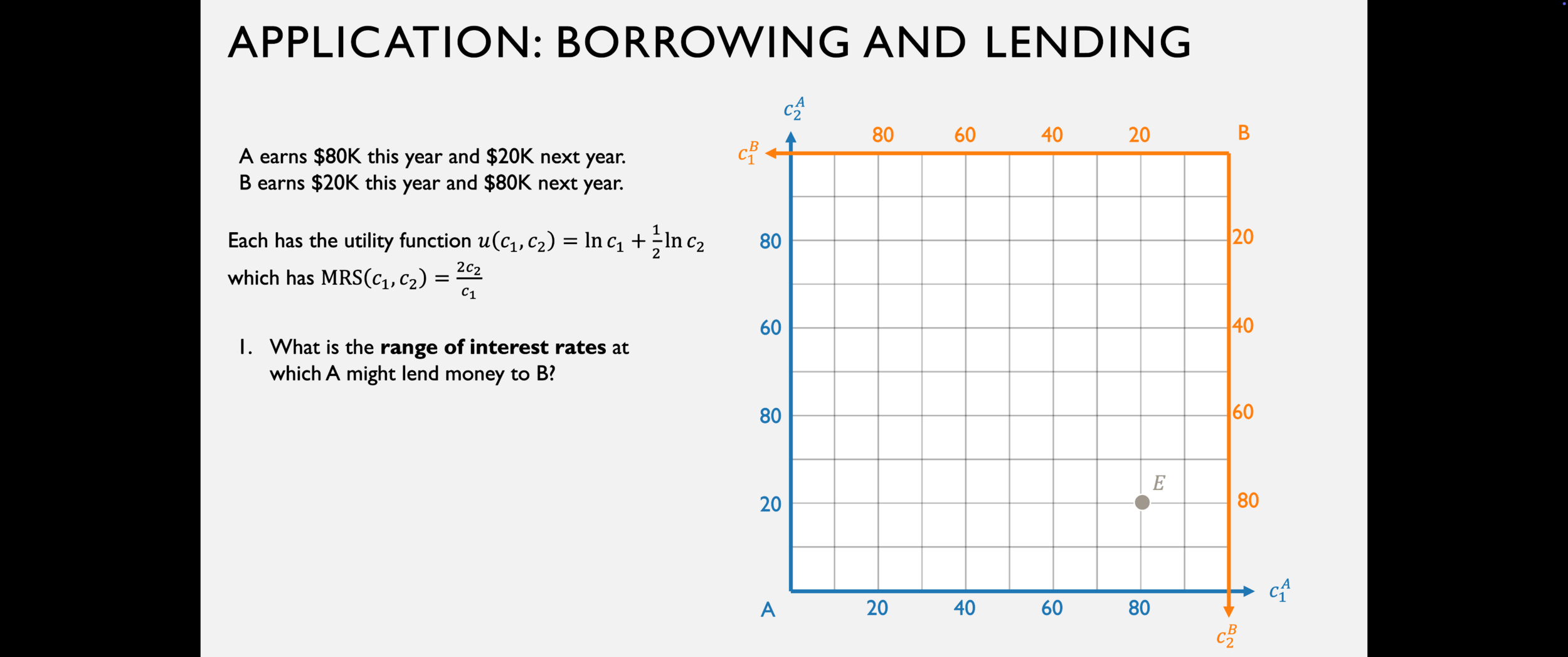

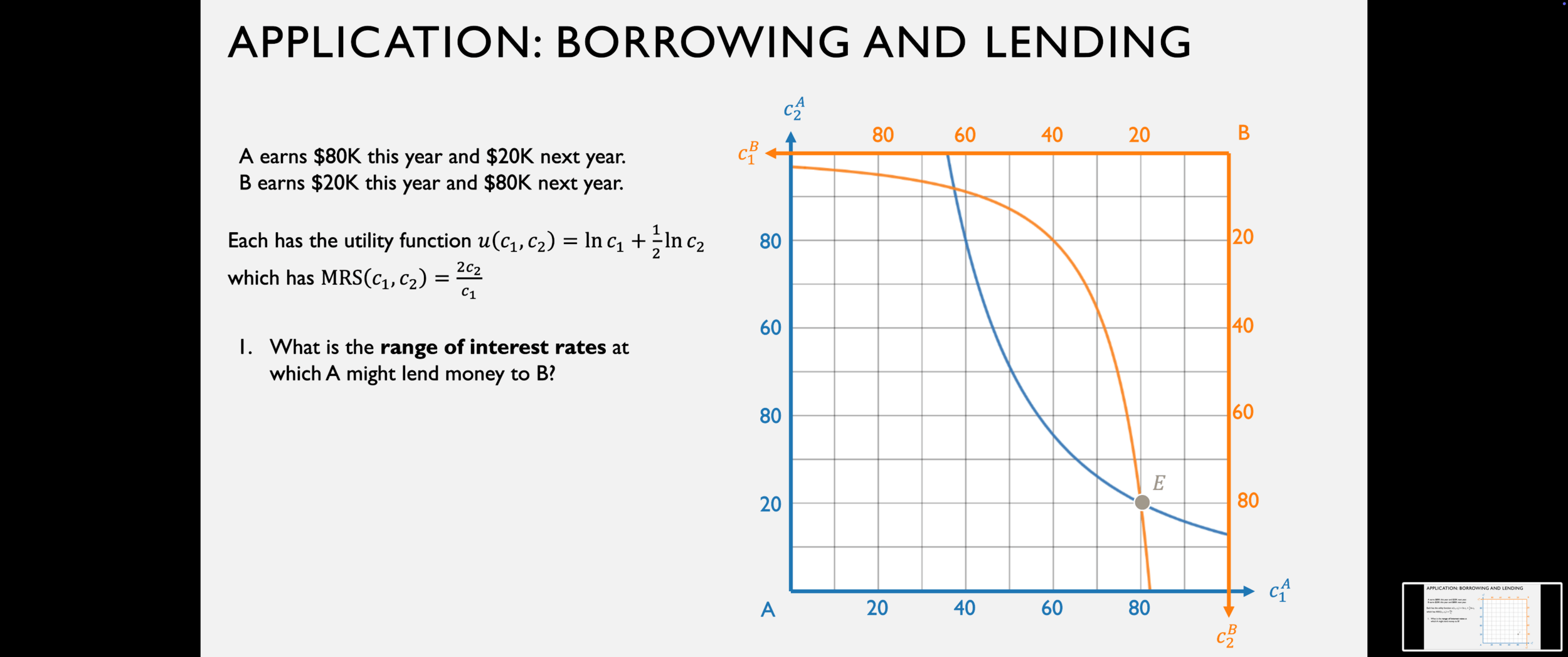

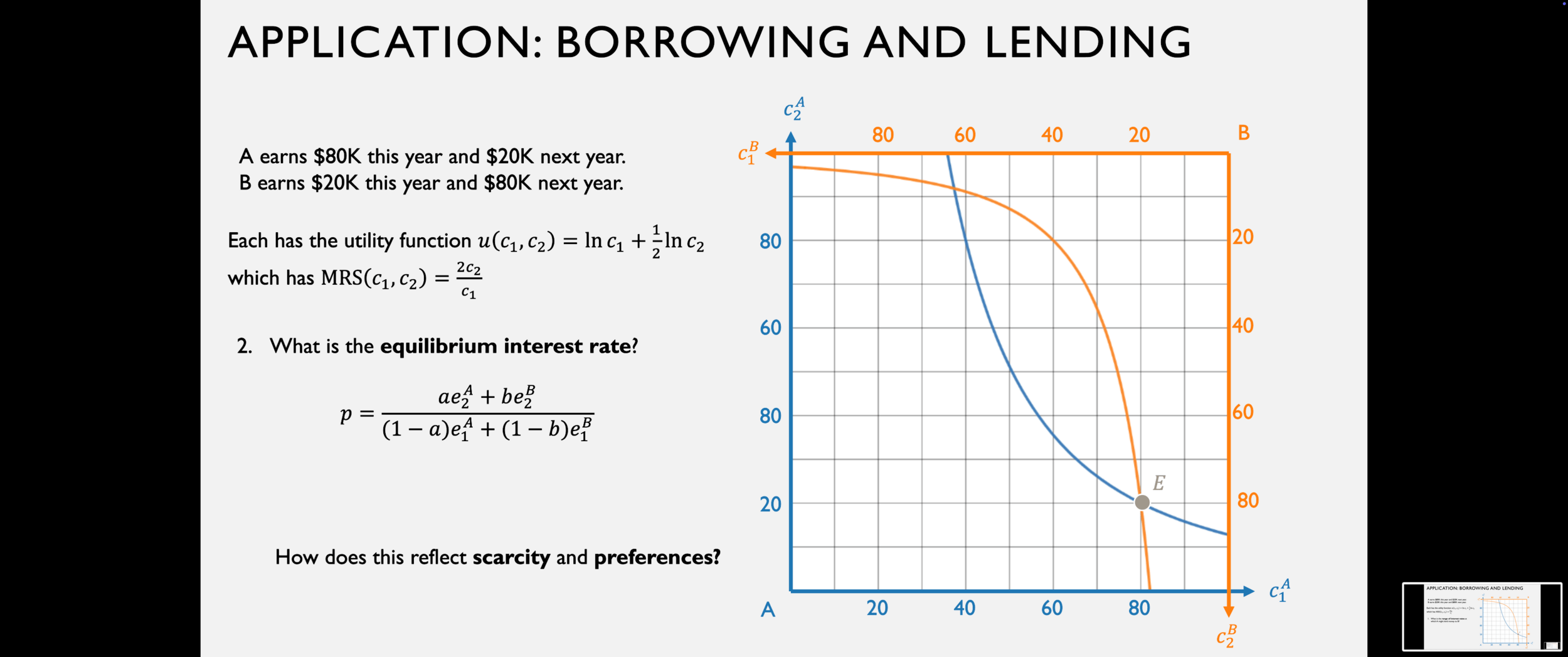

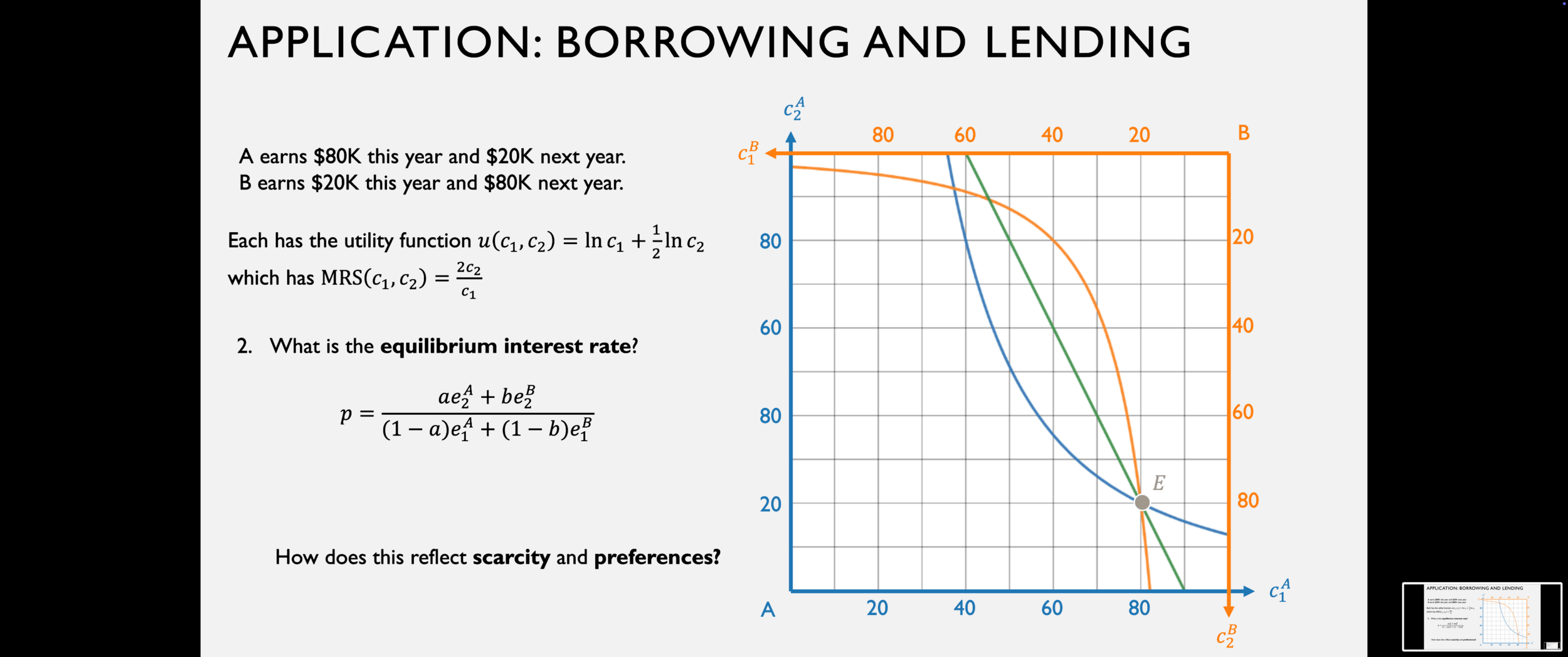

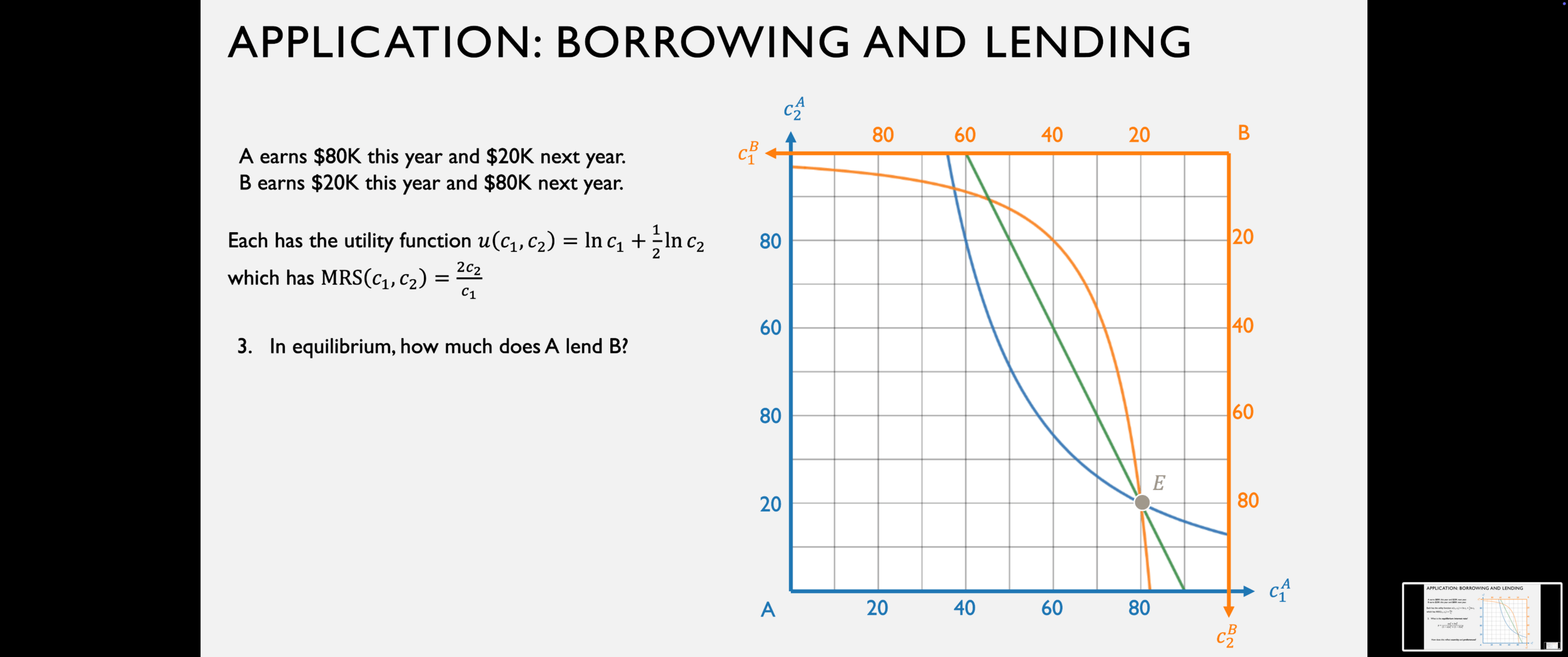

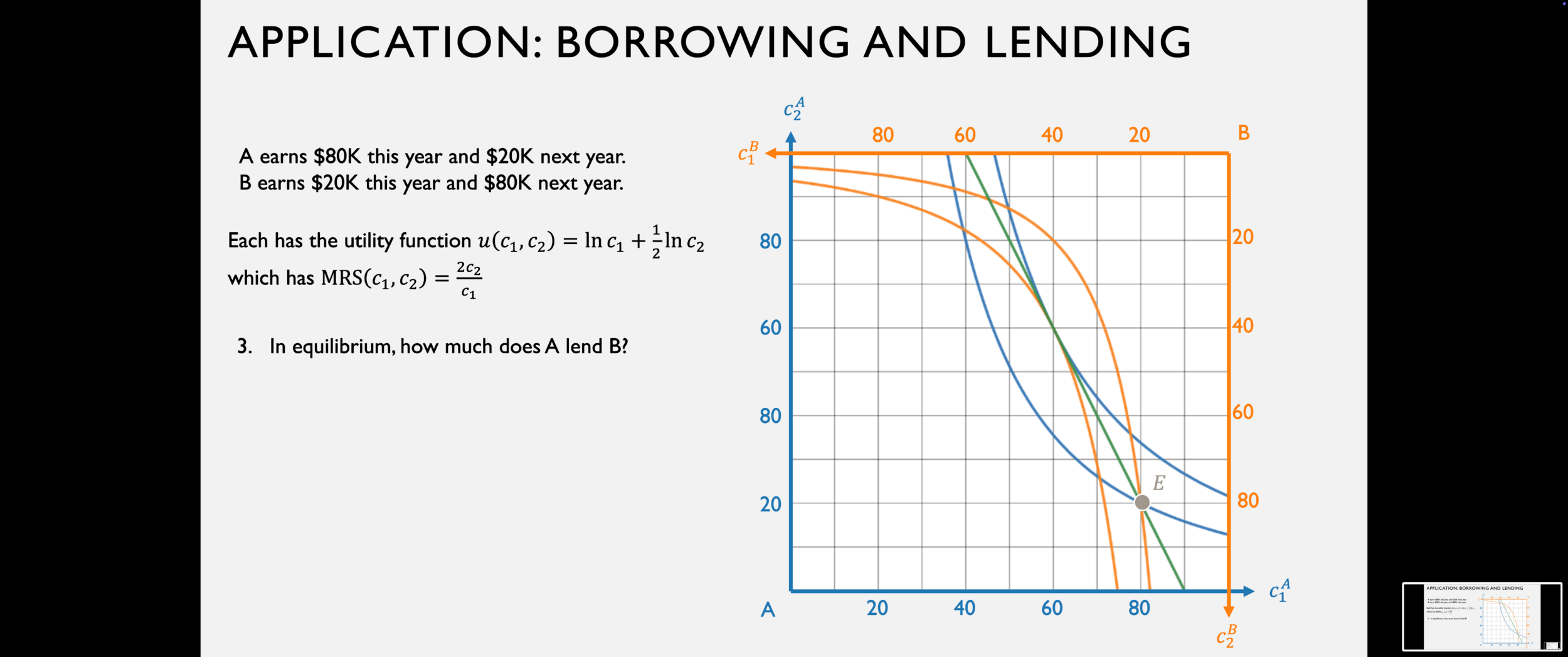

- Application to borrowing and lending

- First and second welfare theorems

Review: Optimization from an Endowment (Lecture 2)

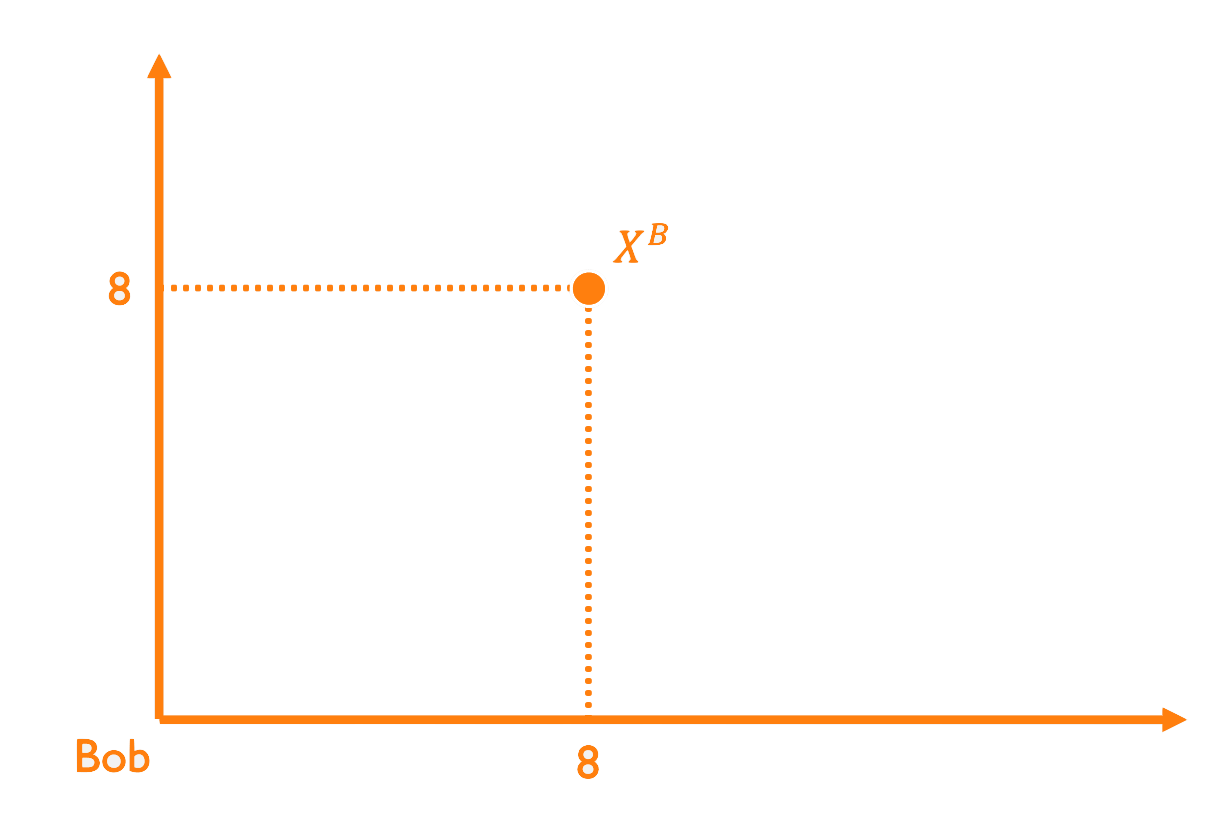

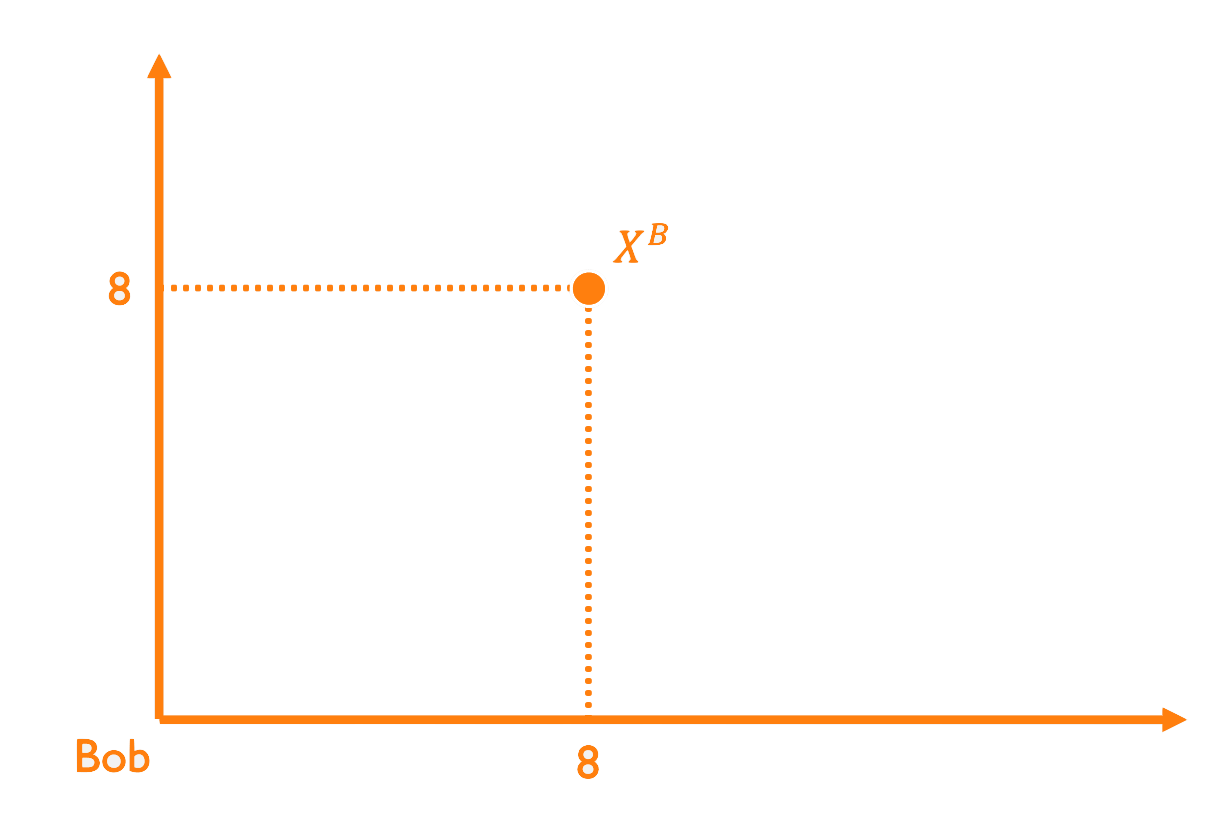

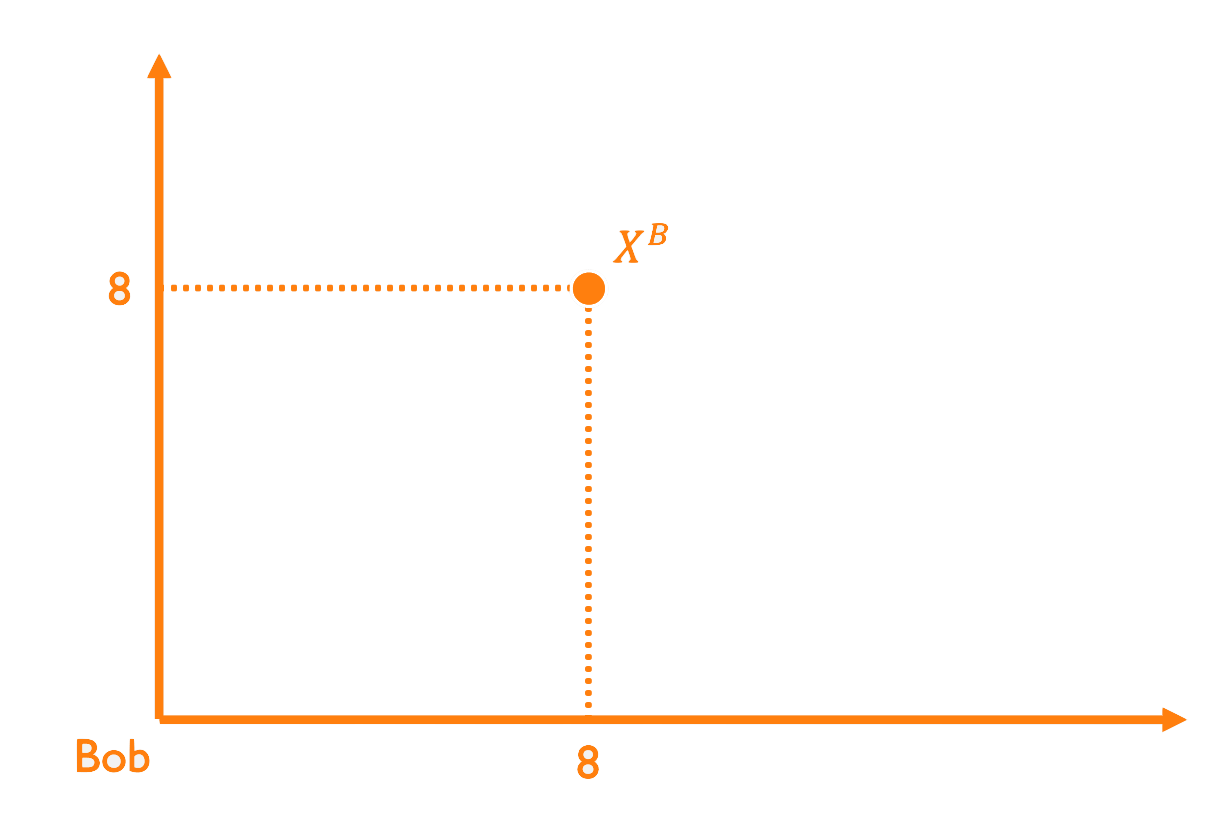

Bob has the Cobb-Douglas utility function \(u(x_1,x_2) = x_1x_2\) and an endowment of (8, 8)

Cobb-Douglas trick:

Since Bob has an endowment of (8,8), his "income" \(m\) is the value of that endowment

For this entire example, let's fix \(p_2 = 4\).

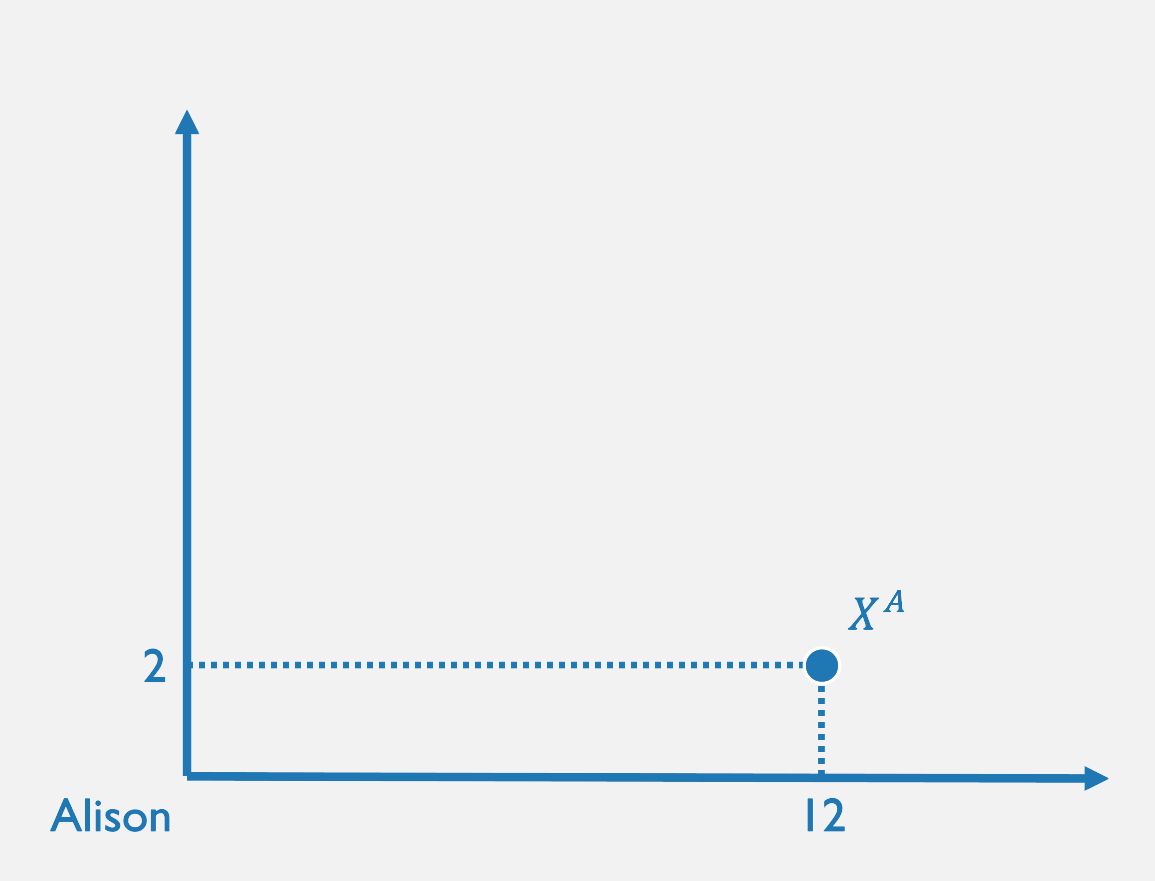

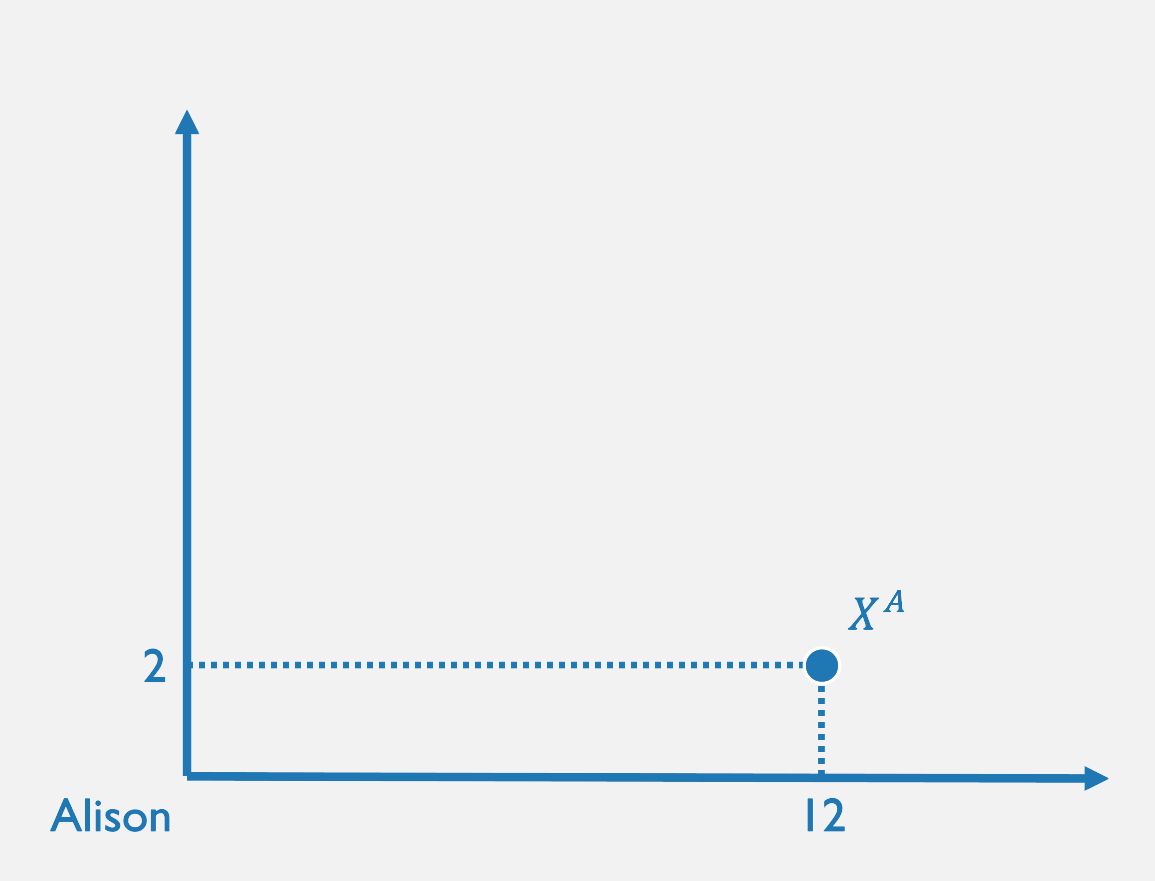

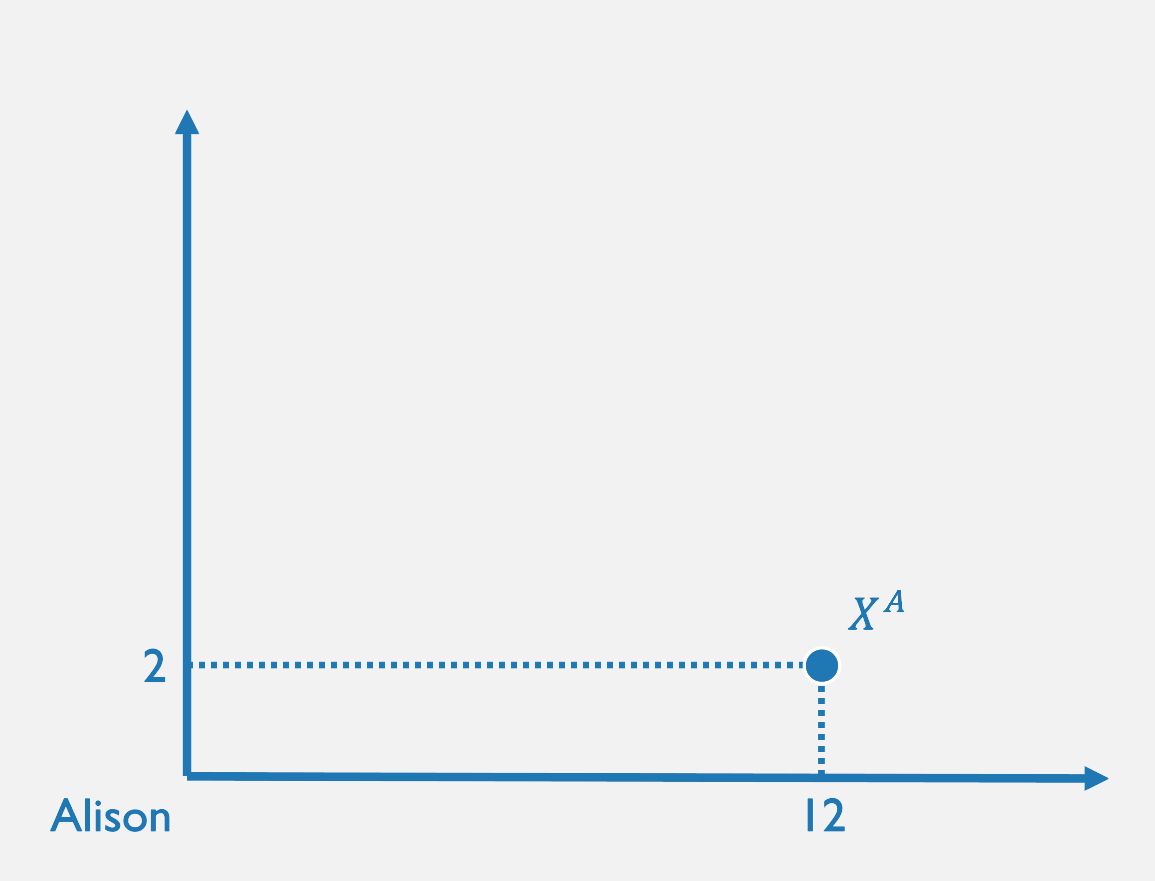

As we go through this example, work with a friend to solve it as well for Alison,

who has an endowment of (12,2).

The total quantity of a good

you want to consume (i.e. end up with)

at different prices.

Gross Demand

The transaction you want to engage in

(the amount you want to buy or sell)

at different prices.

Net Demand

Bob has the Cobb-Douglas utility function \(u(x_1,x_2) = x_1x_2\) and an endowment of (8, 8)

When is this positive?

So, Bob wants to buy good 1 when \(p_1 < 4\), and sell it when \(p_1 > 4\).

Remember that his utility function is \(u(x_1,x_2) = x_1x_2\), his endowment is (8,8), and \(p_2 = 4\).

MRS at endowment =

Price ratio =

Bob's MRS at his endowment is

Bob's net demand is

Bob

Endowment: (8,8)

Utility function: \(u(x_1,x_2) = x_1x_2\)

Bob's gross demand for good 1 is:

Bob

Endowment: (12, 2)

Utility function: \(u(x_1,x_2) = x_1x_2\)

Alison's gross demand for good 1 is:

Alison

Alison's MRS at her endowment is:

Alison's net demand is:

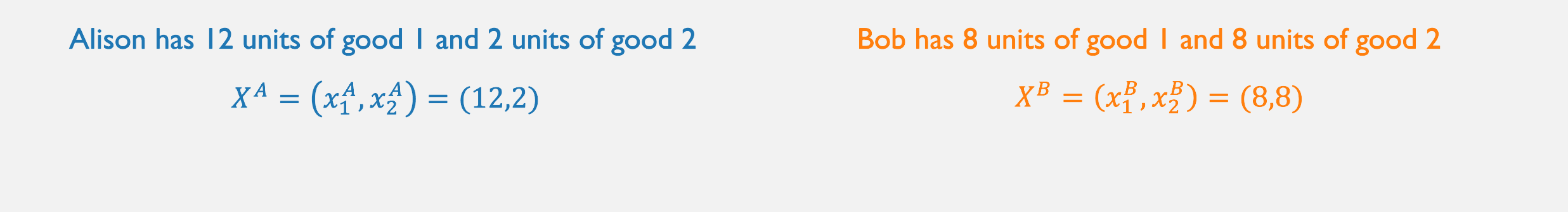

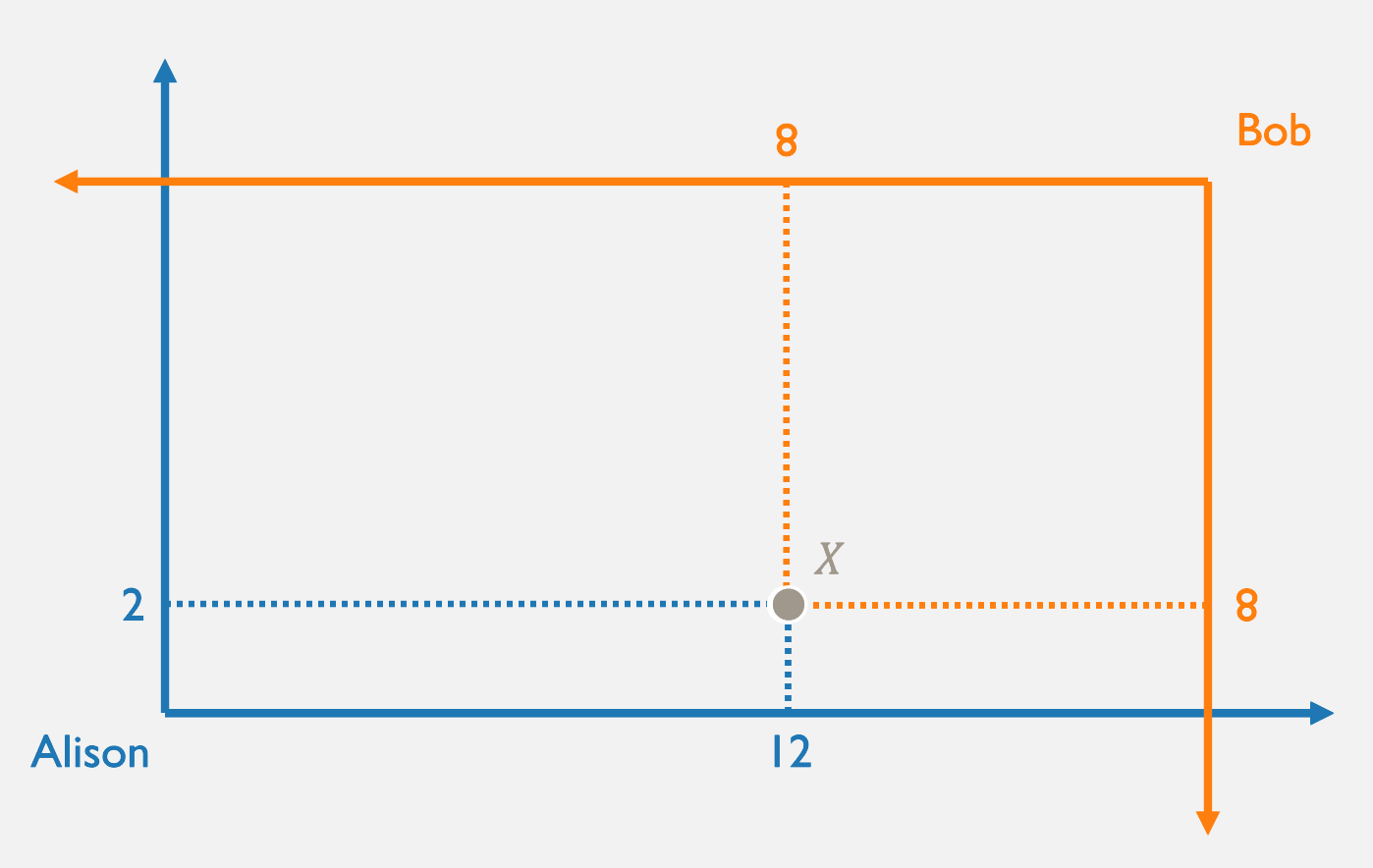

From Bundles to Allocations

- A bundle is a vector of goods

consumed by an individual agent. - An allocation is a vector of bundles

consumed by multiple agents.

From Bundles to Allocations

From Bundles to Allocations

From Bundles to Allocations

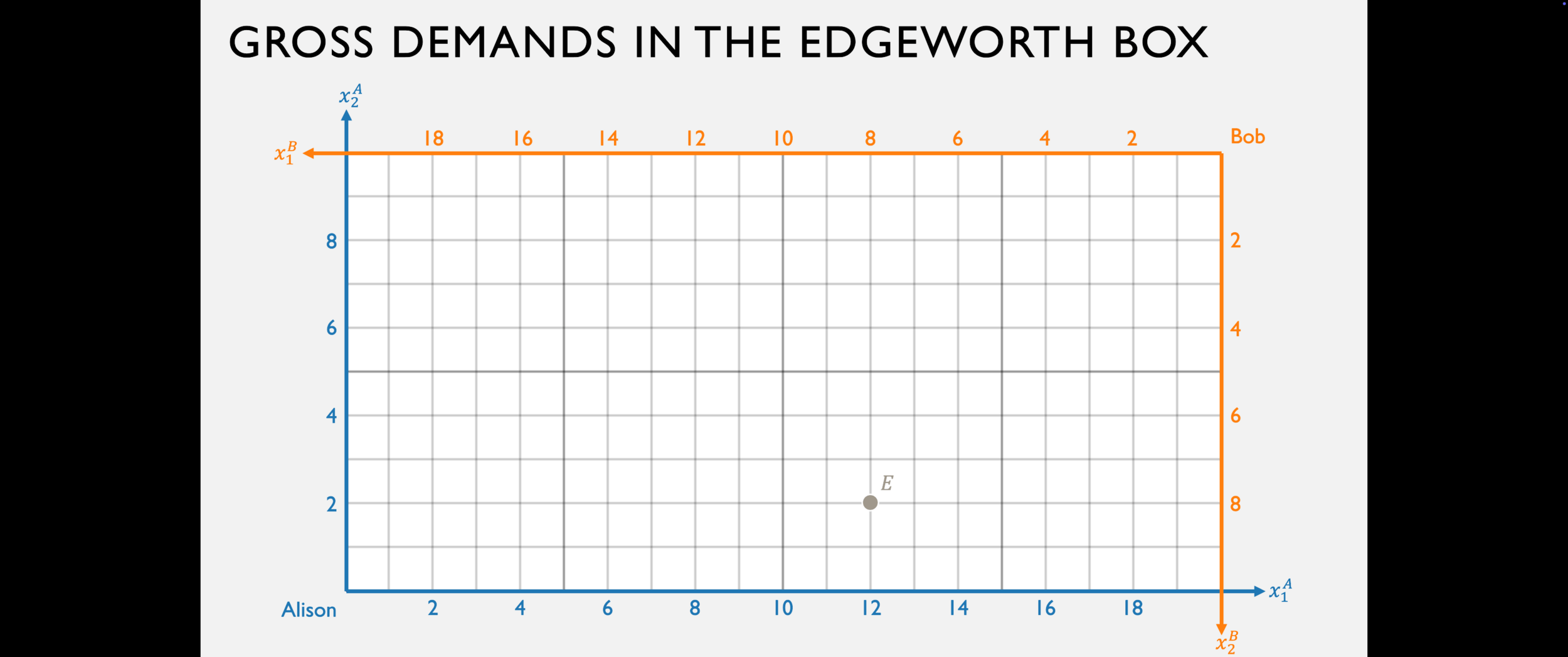

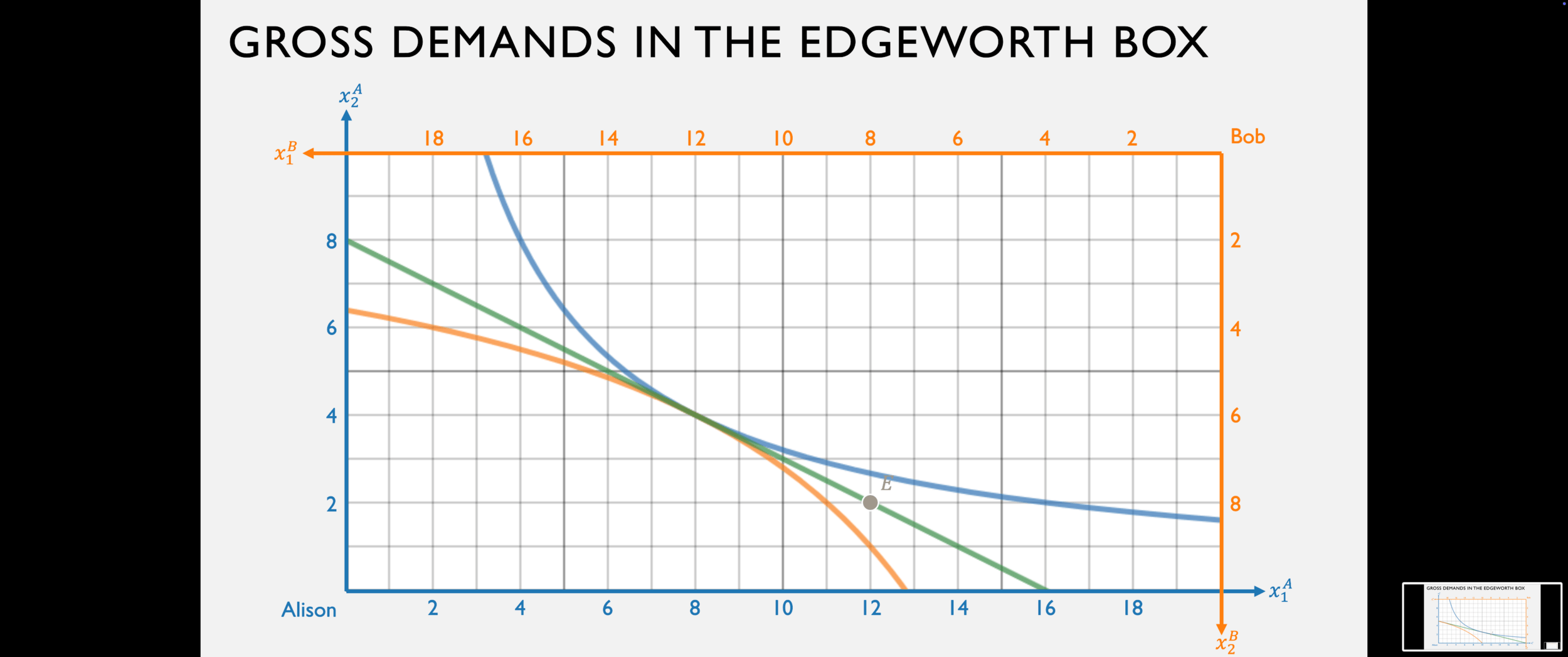

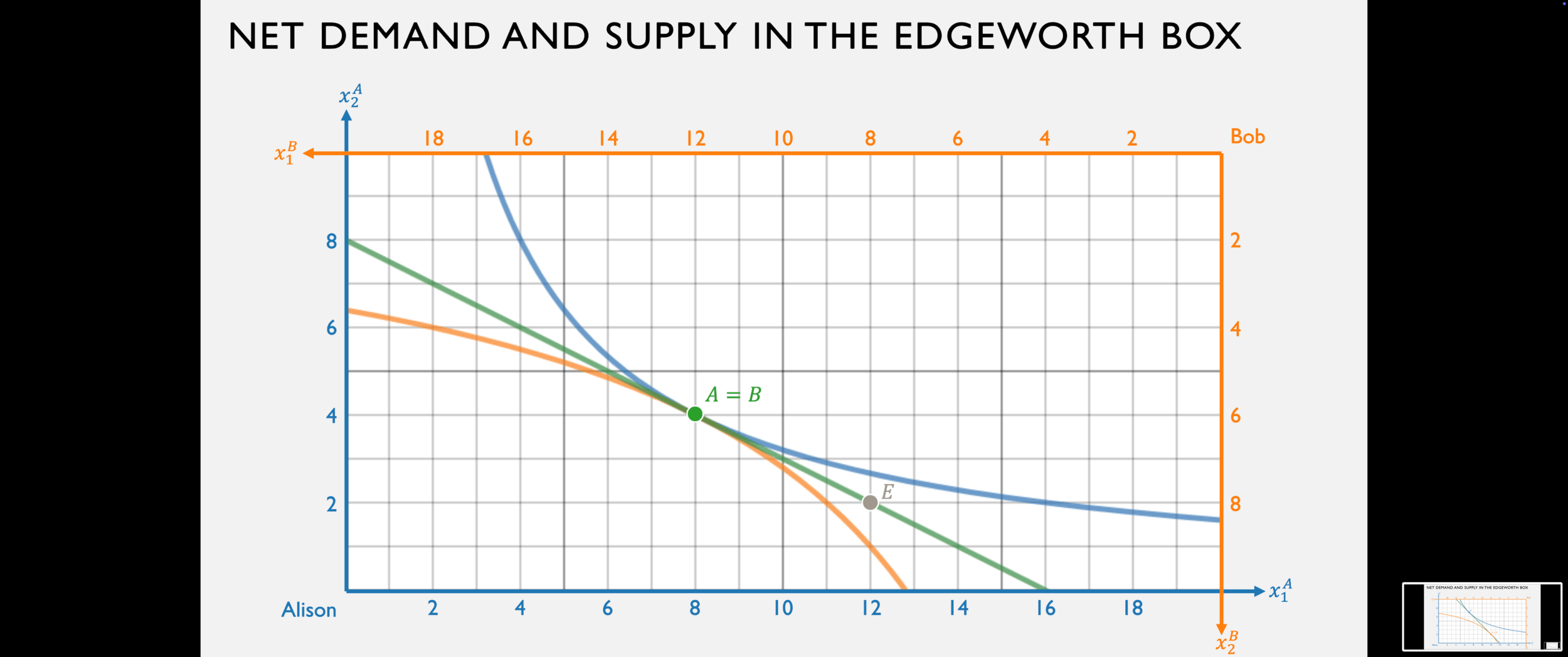

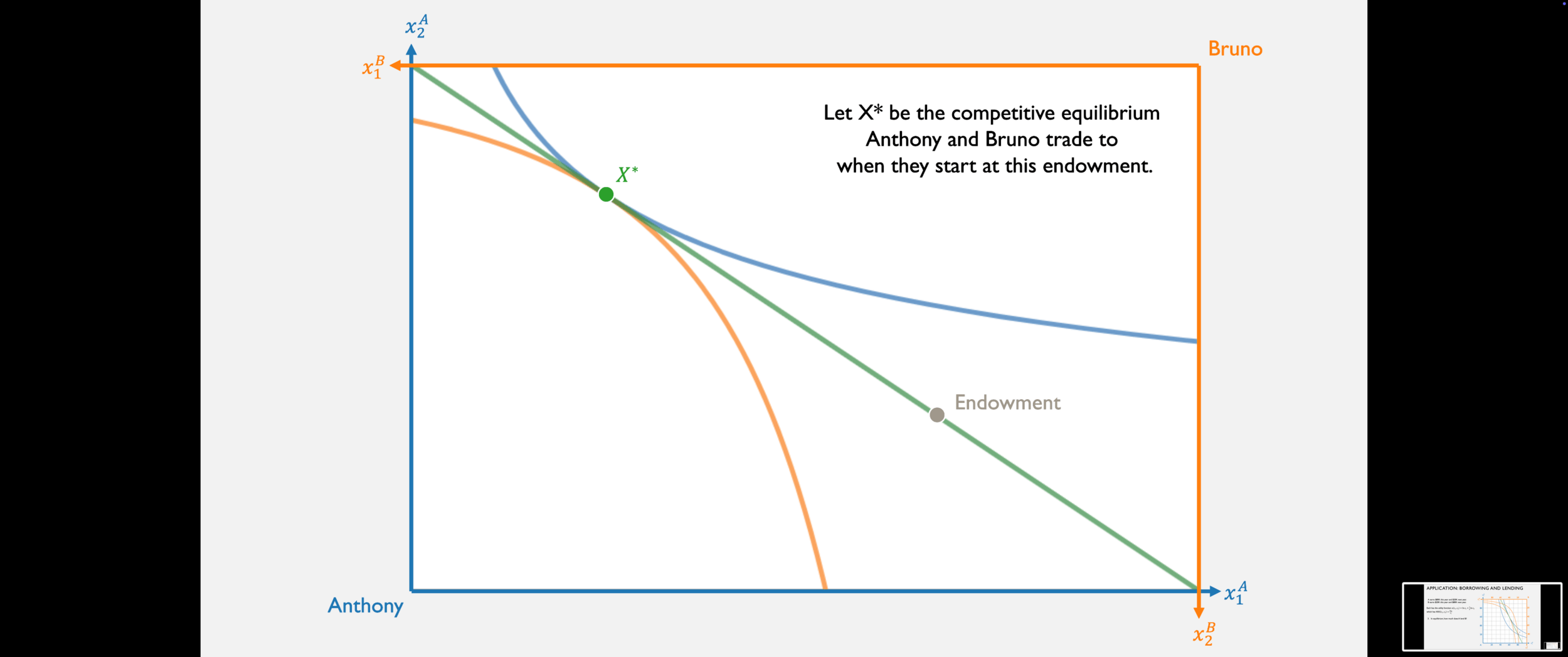

Trade in the Edgeworth Box

- Suppose both agents believe they can trade at some price ratio \(p_1/p_2\).

- Then they share a common budget line in the Edgeworth Box.

...but where do they want to trade to?

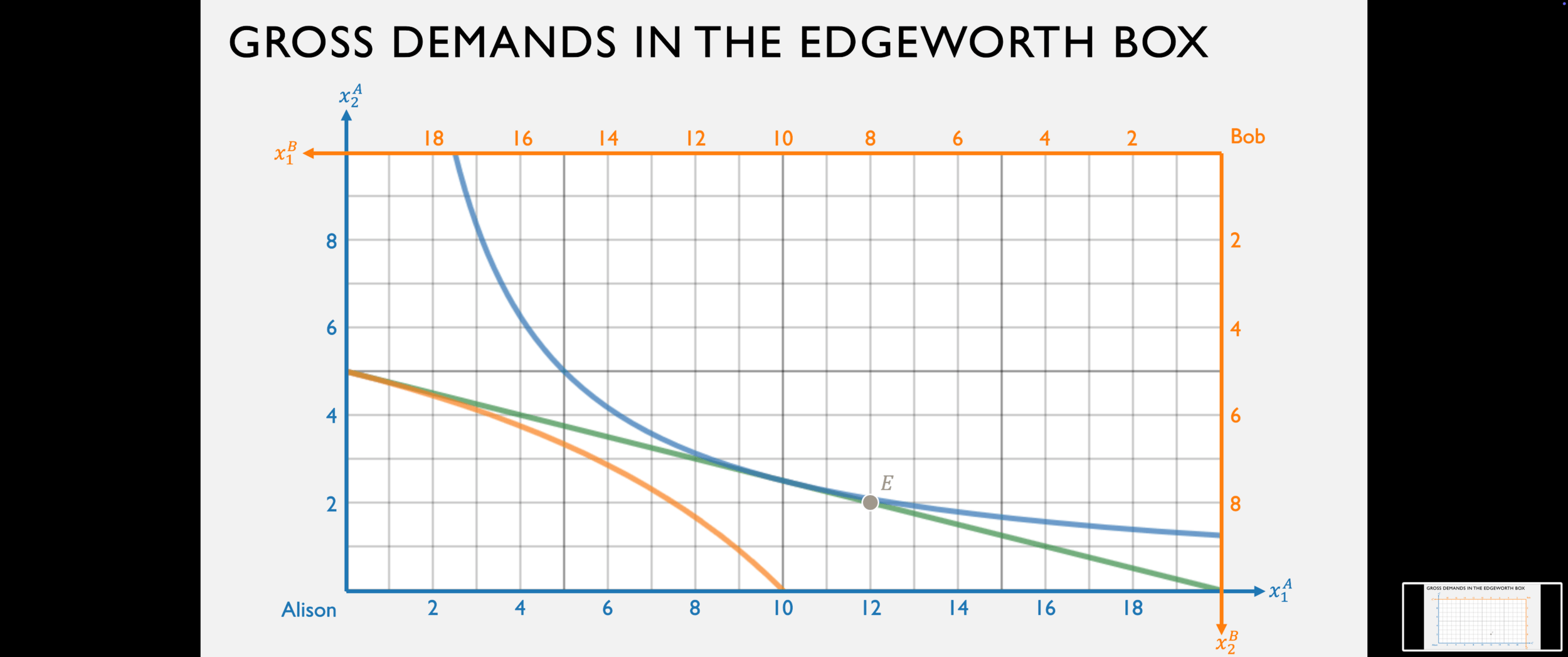

Preferences in the Edgeworth Box

What does the "lens" of overlap represent?

How is the existence of this lens related to

the agents' marginal rate of substitution (MRS) at point \(X\)?

Bob's MRS at his endowment is

Bob

Bob

Alison

Alison's MRS at her endowment is:

Alison wants to sell good 1 if:

Bob wants to buy good 1 if:

Between these two price ratios, Alison wants to sell good 1 and Bob wants to buy good 1.

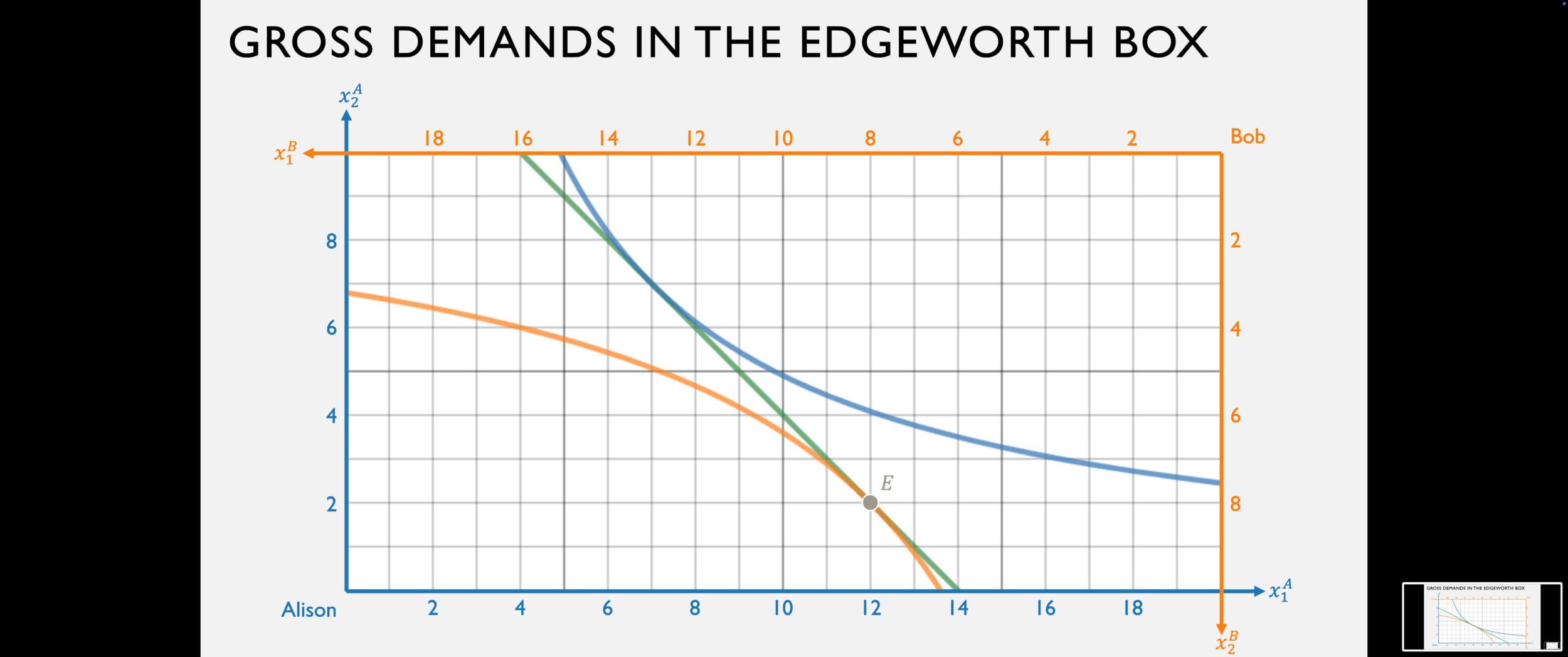

Bob's gross demand for good 1 is:

Bob

Alison's gross demand for good 1 is:

Alison

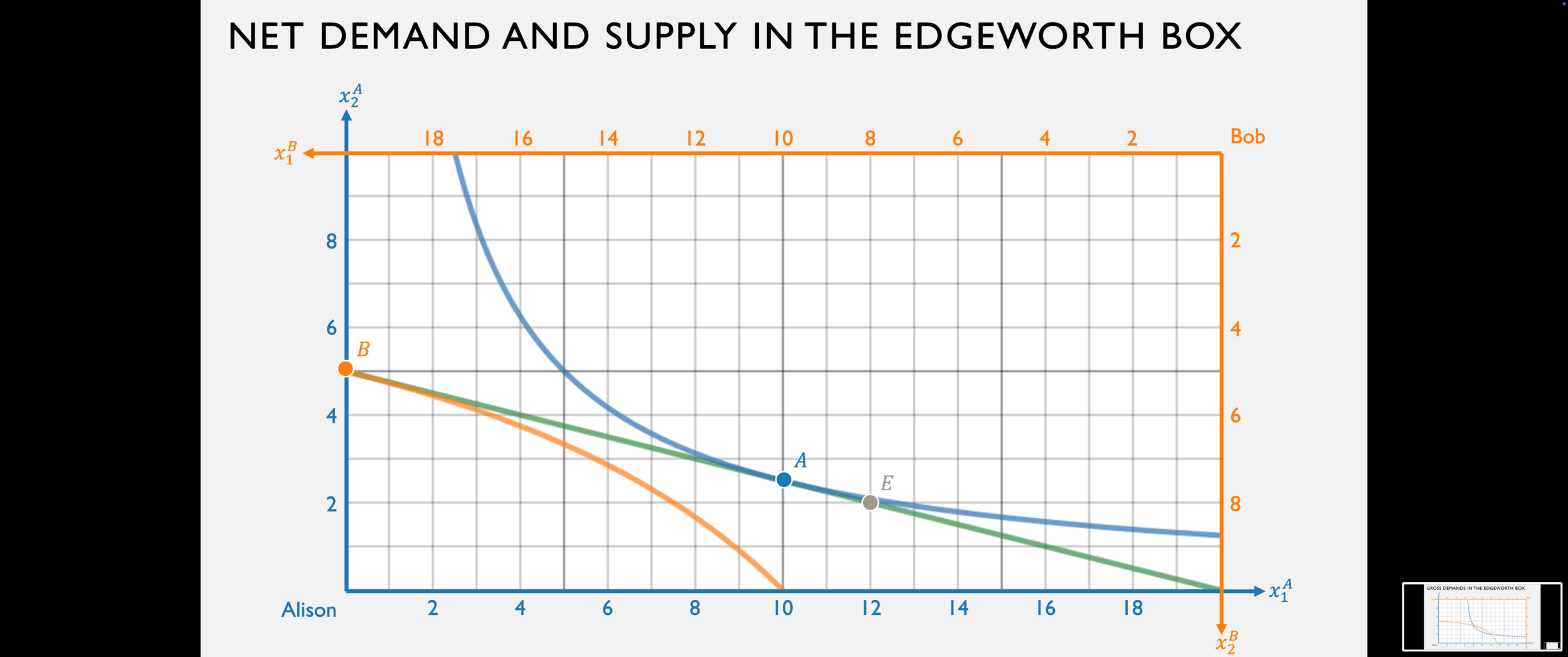

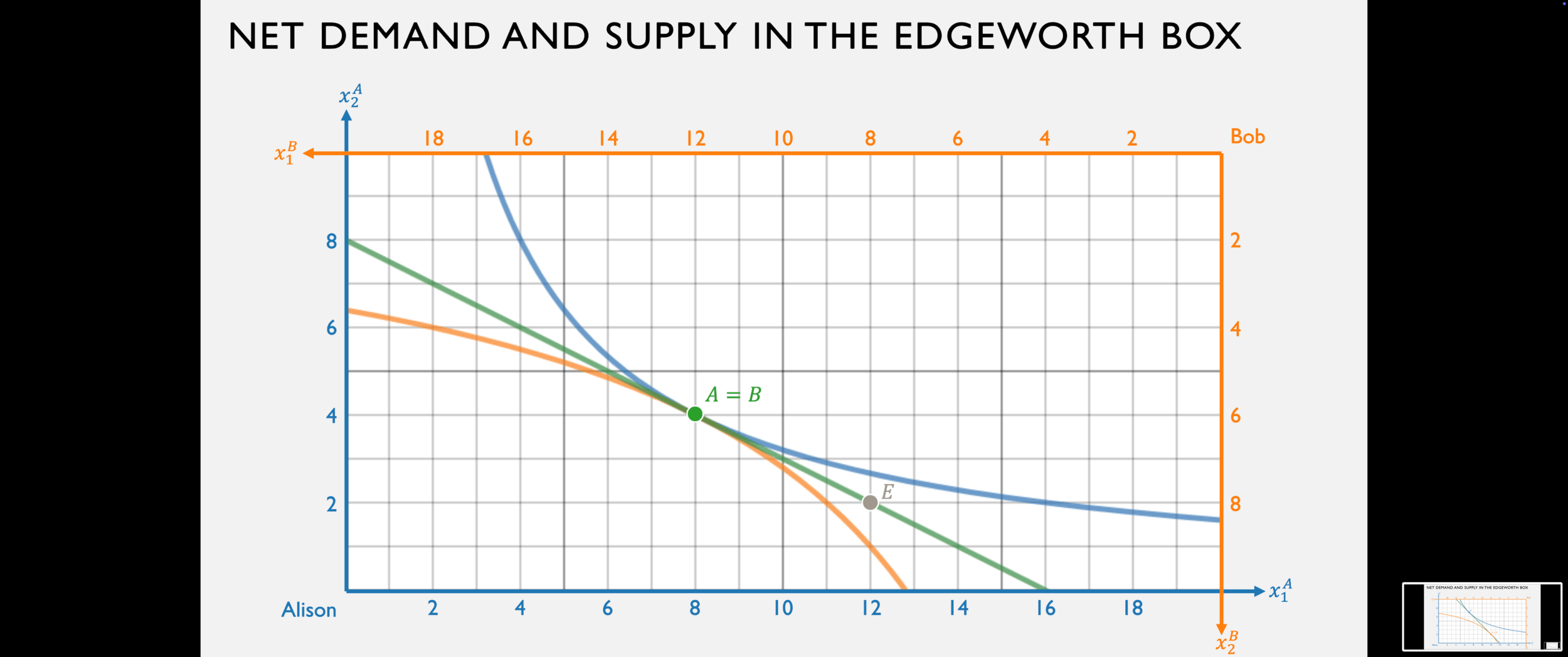

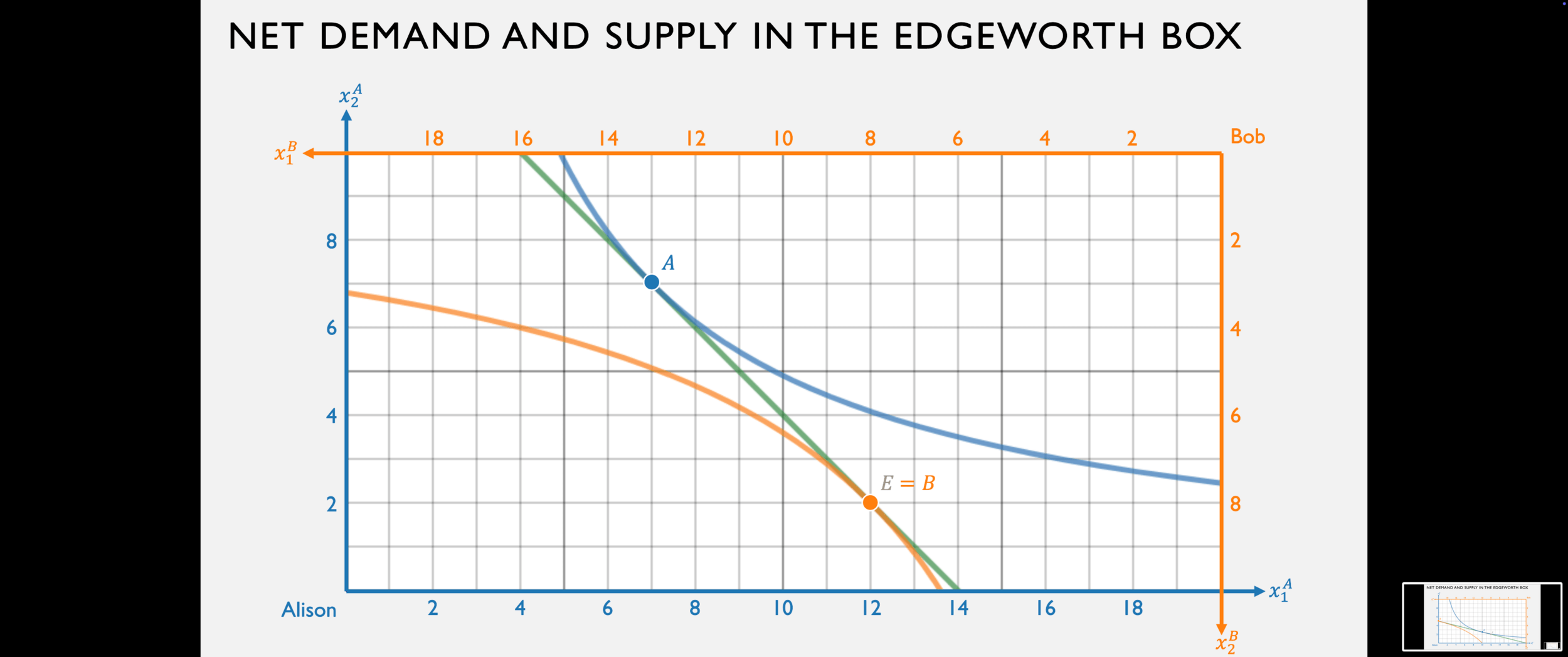

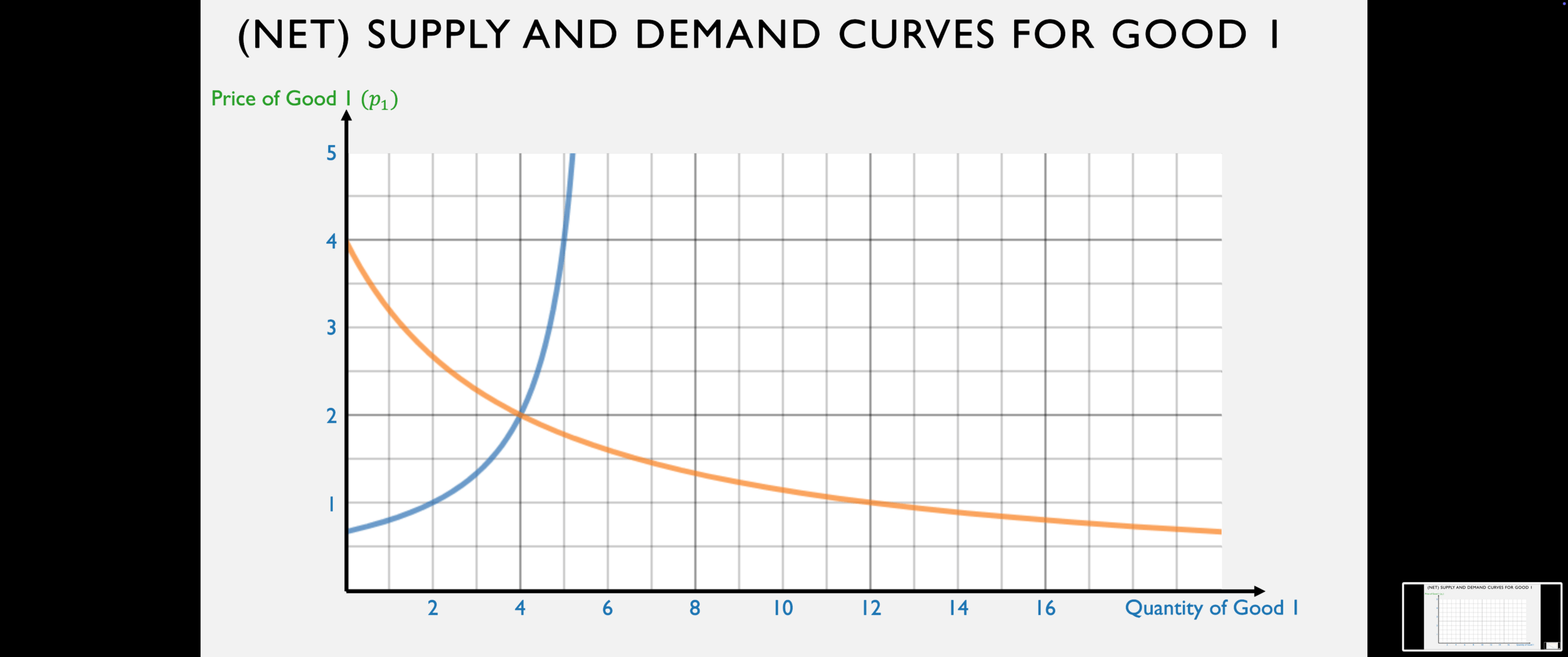

Net Demand and Supply

- The gross demands tell us where each agents wants to trade to at any given price ratio.

- We can think about this same data in terms of net demand and net supply.

Bob's gross demand for good 1 is:

Alison's gross demand for good 1 is:

His net demand for good 1 is:

Her net supply of good 1 is:

Bob demands 12

Alison supplies 2

Bob's gross demand for good 1 is:

Alison's gross demand for good 1 is:

His net demand for good 1 is:

Her net supply of good 1 is:

Bob demands 4

Alison supplies 4

Bob's gross demand for good 1 is:

Alison's gross demand for good 1 is:

His net demand for good 1 is:

Her net supply of good 1 is:

(Bob demands 0)

Alison supplies 5

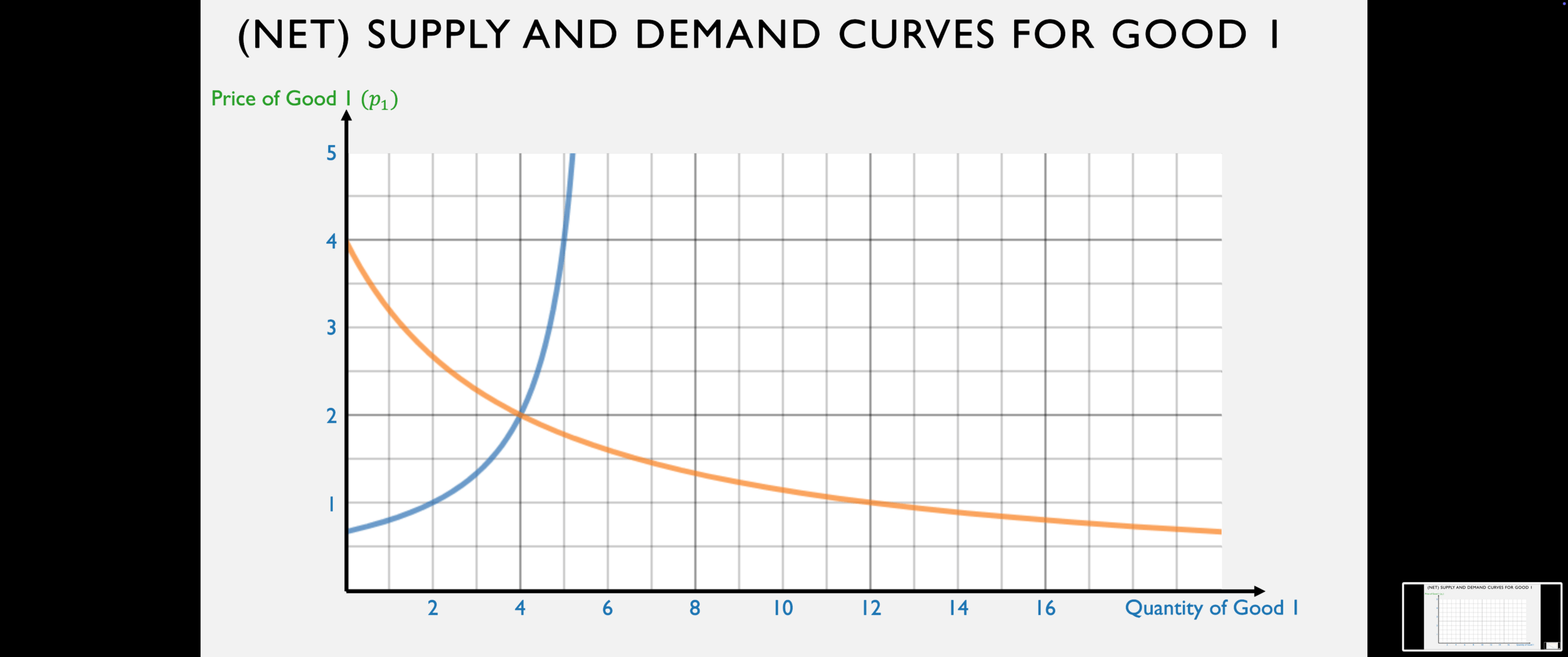

Bob's net demand for good 1 is:

Alison's net supply of good 1 is:

Solving for Equilibrium

Bob's net demand for good 1 is:

Alison's net supply of good 1 is:

Just like we always do, set these equal to one another and solve for the equilibrium price!

Bob's net demand for good 1 is:

Alison's net supply of good 1 is:

Just like we always do, set these equal to one another and solve for the equilibrium price!

Solving for general Cobb-Douglas utility functions

The parameter \(a\) measures how much A likes good 1,

and the parameter \(b\) measures how much B likes good 1.

Solving for general Cobb-Douglas utility functions

The parameter \(a\) measures how much A likes good 1,

and the parameter \(b\) measures how much B likes good 1.

Formula for the equilibrium price ratio:

In our example with Alison and Bob, we had: \(a = {1 \over 2}, e_1^A = 12, e_2^A = 2; b = {1 \over 2}, e_1^B = 8, e_2^B = 8\):

In this example, both Alison and Bob liked the two goods equally. Why wasn't the price ratio 1?

Solving for general Cobb-Douglas utility functions

The parameter \(a\) measures how much A likes good 1,

and the parameter \(b\) measures how much B likes good 1.

Formula for the equilibrium price ratio:

What happens to the relative price of good 1

if people like good 1 more (that is, \(a\) and \(b\) are higher)?

What happens to the relative price of good 1

if there is more good 1 in the world (that is, \(e_1^A\) and \(e_1^B\) are higher)?

In competitive equilibrium in an exchange economy,

the price ratio reflects two fundamental things:

the preferences of the agents, and

the relative scarcity of the goods.

Fundamental Theorems of Welfare Economics

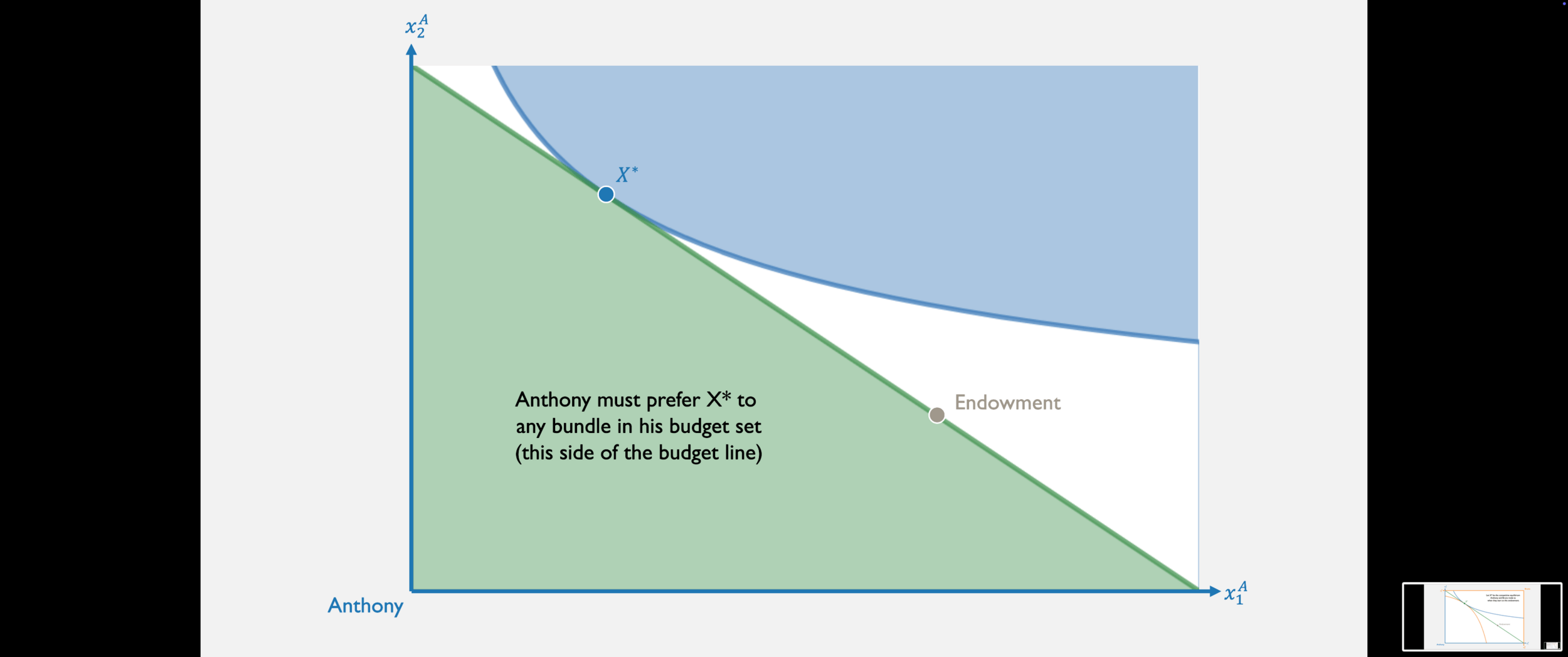

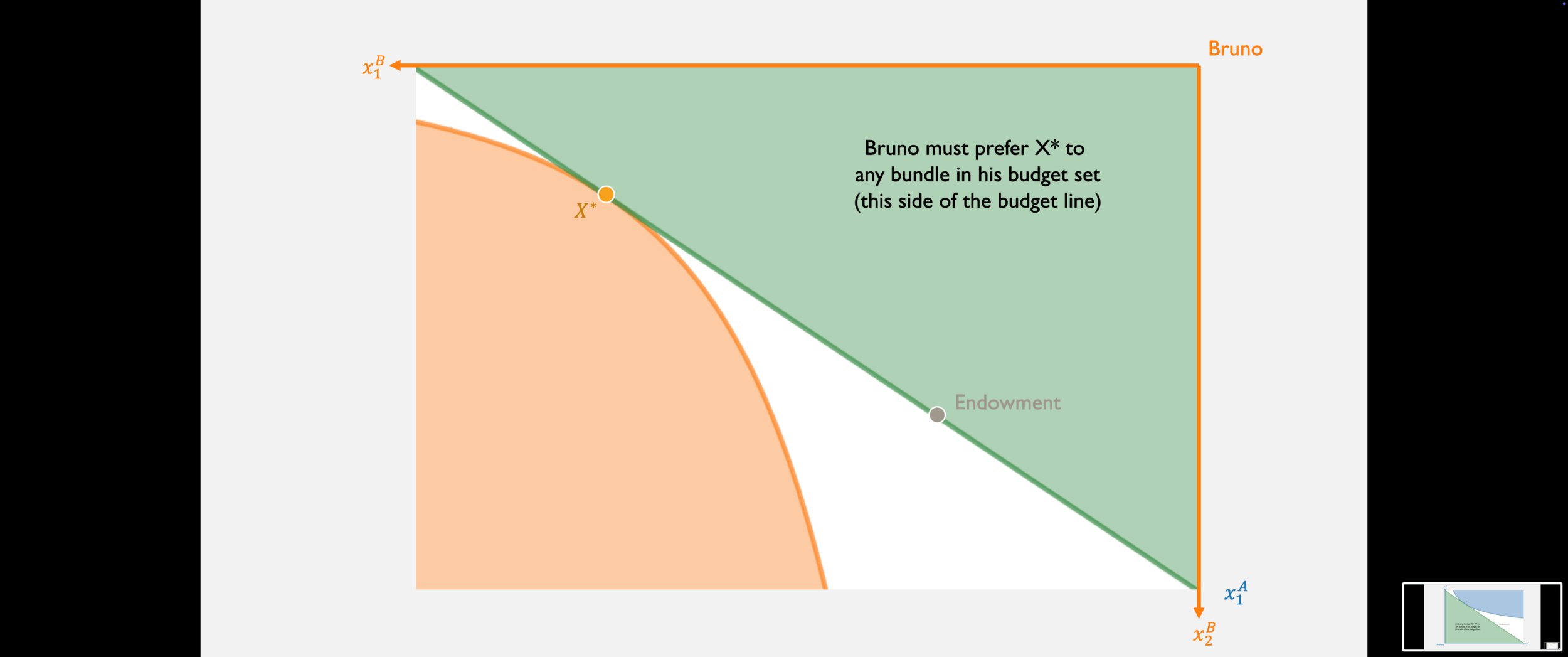

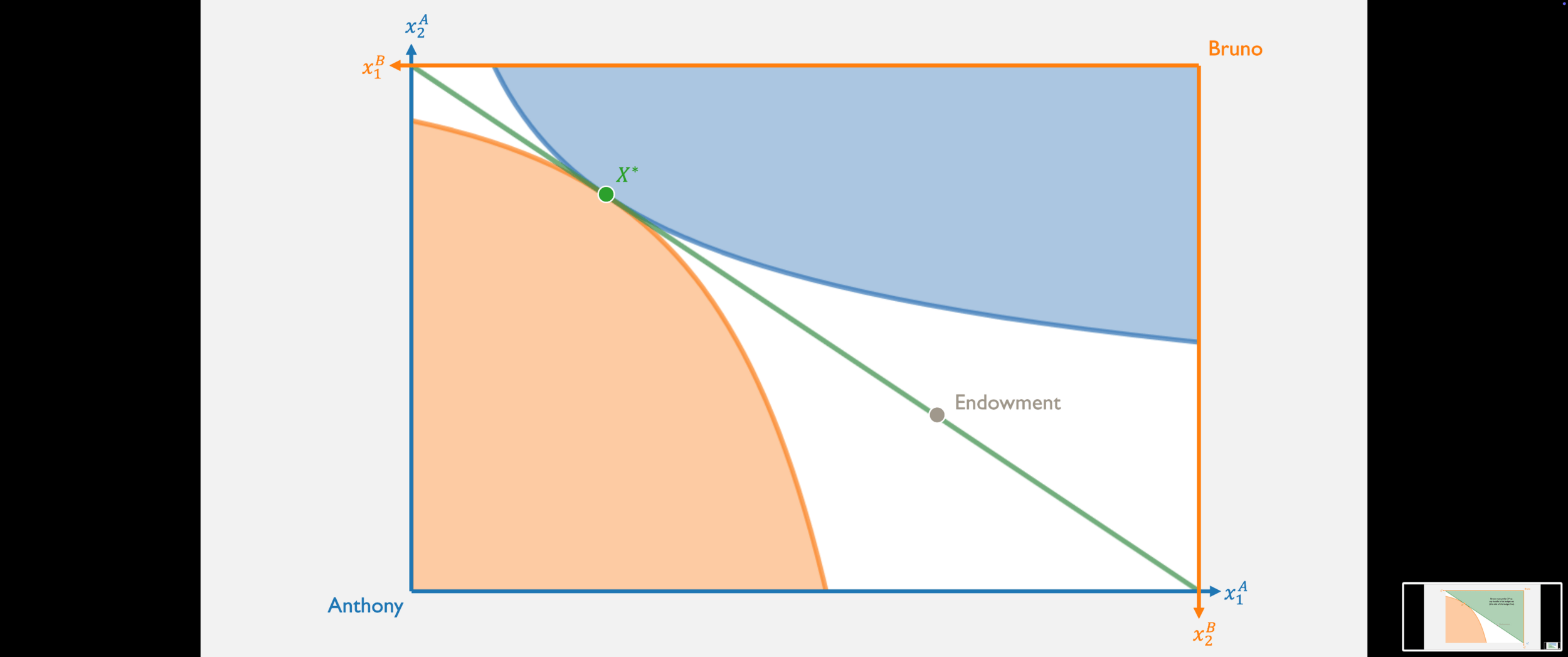

- First Welfare Theorem: If an allocation \(X^*\) is a competitive equilibrium, then it is Pareto efficient.

- Second Welfare Theorem: When preferences are convex, any Pareto efficient allocation is an equilibrium for some set of prices and some endowment.

The First Welfare Theorem

- Formally: If an allocation \(X^*\) is a competitive equilibrium, then it is Pareto efficient.

- Intuitively: Markets are efficient. If you just let everyone do what's best for themselves, you end up with a Pareto efficient outcome. Libertarianism FTW!

Since Anthony's preferred set is entirely on this set of the budget line...

...and Bruno's preferred set is entirely on this side of the budget line...

...then X* must be Pareto efficient!

[. ]

WHAT'S NEXT?

Econ 51 | 06 | Competitive Equilibrium

By Chris Makler

Econ 51 | 06 | Competitive Equilibrium

Efficiency and Equity in the Edgeworth Box

- 1,089