separate - and still unequal

Cara Fitzpatrick, @Fitz_ly; Lisa Gartner, @lisagartner;

Michael LaForgia, @laforgia_

Michael LaForgia, @laforgia_

how failure factories got started

1. knowing when a story demands

a deeper look

- Something has to be really, clearly wrong – and everybody admits it's wrong.

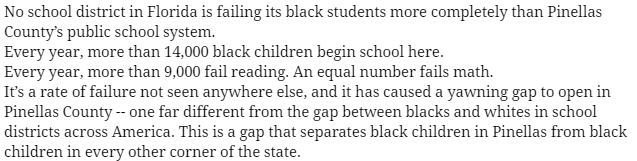

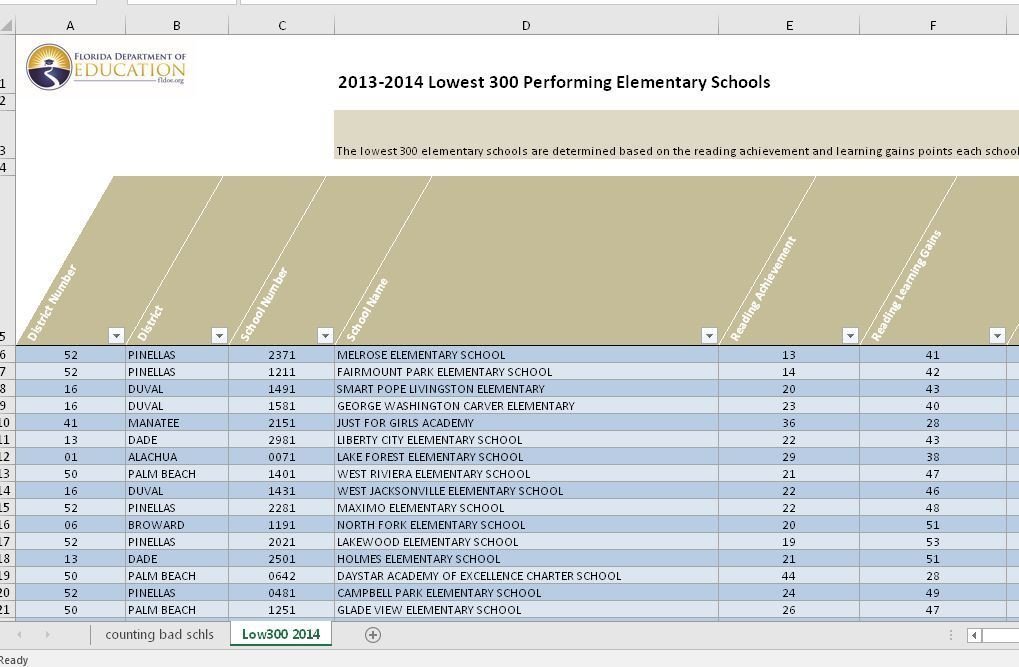

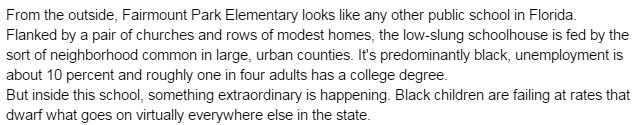

- In 2014, five of the worst schools in Florida are clustered in a 6-square-mile area in St. Petersburg's black neighborhoods.

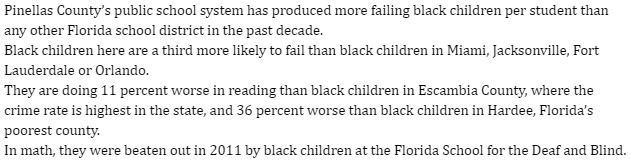

- Black kids in Pinellas County did worse on tests than black kids virtually anywhere else in Florida.

- There has to be reason to believe the phenomenon is part of a wider pattern or trend that has gone undiscovered or unreported on.

- Test scores in the past 10 years showed steady improvement until a point, around 09-10 and 10-11, when black scores started dropping dramatically.

- There has to be an actor – the thing that is wrong is the direct result of action that a person, company, government agency or other entity took or, just as importantly, did not take.

- Policy archaeology. Hardest part of doing this series.

2. getting started

- Formulate a hypothesis

- The five schools are among the worst in Florida because the school district is neglecting them and didn't keep promises.

- Figure out how things are supposed to work.

- Surveyed a dozen or more experts, and other Florida school districts, to learn what policies and practices should be in place to guarantee students in low-income schools don't start failing en masse.

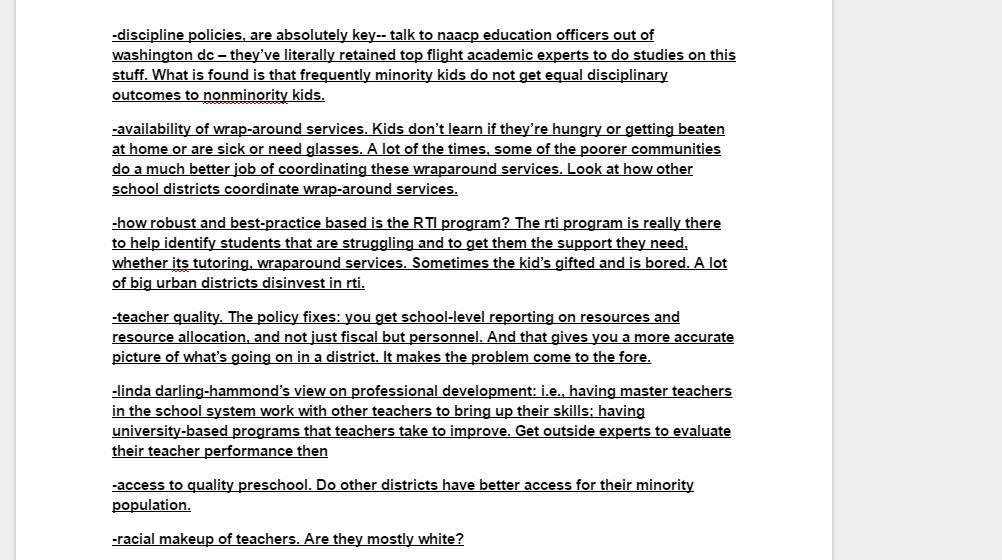

- What are the key policy areas that most affect how well kids in low-income schools learn?

another part of getting started ...

- Approach your subject early. Be up front.

- Have some knowledge and impressions gleaned from expert interviews, records and data.

- Know that there’s probably a wider problem within the system you’re looking at, but don’t assume the worst.

- Assume the best. Keep an open mind, and let your subject prove to you that in fact they are the actual worst

- This stakes out the MORAL HIGH GROUND. You don’t have a secret agenda. You’re not sneaking around or displaying a gotcha mentality.

by the way ...

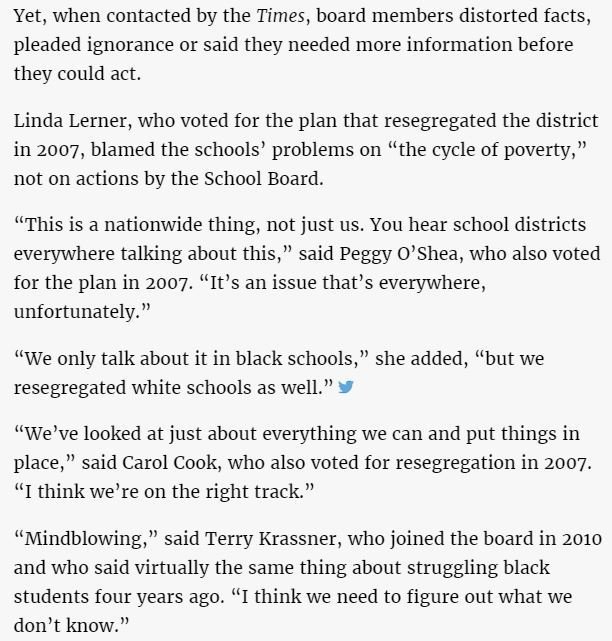

If, in these early interactions, your subject or subjects start lying to you, or saying outrageous things, keep your righteousness

to yourself.

to yourself.

Don't interrupt.

Perk up, call it interesting and let them keep talking.

Often they'll think they're getting one over on you, and expound or double down.

3. proving your story

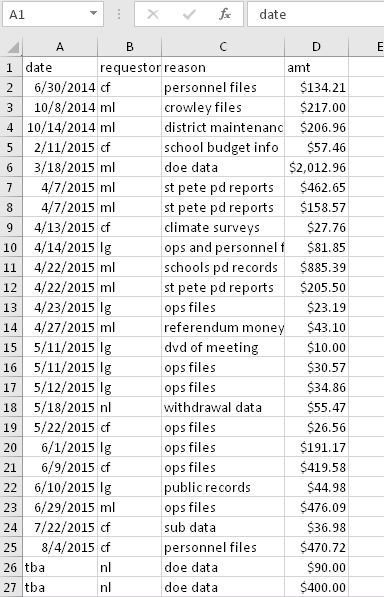

- Don’t be a wimp when confronted with high costs – either of money or of time.

- If you’re already at this point, then the story is worth it.

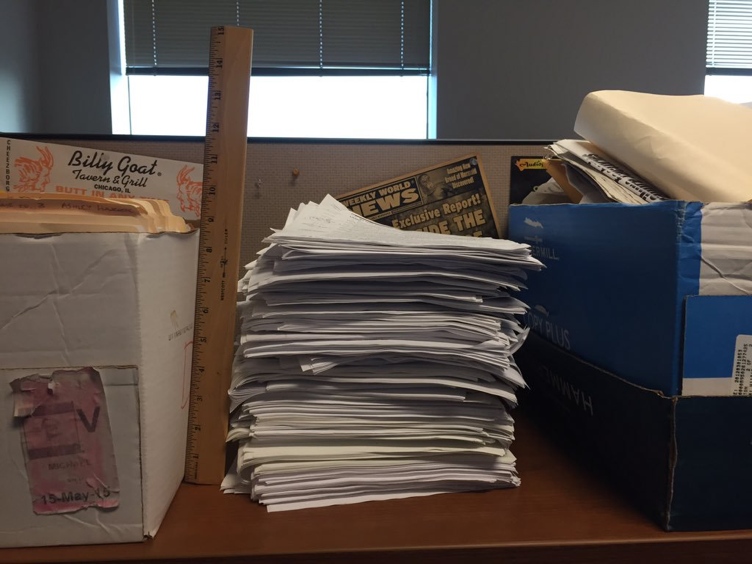

- We got a grant to cover some of the more than $10,000 we spent on data and records requests.

- Never shy away from doing the crazy-hard thing that will lock down your authority to tell the story.

EMBRACE USING DATA

Forget the term "data journalism."

These days, on most beats, data is the most authoritative source. If you're not regularly interviewing it, you're not doing your job as well as you could be.

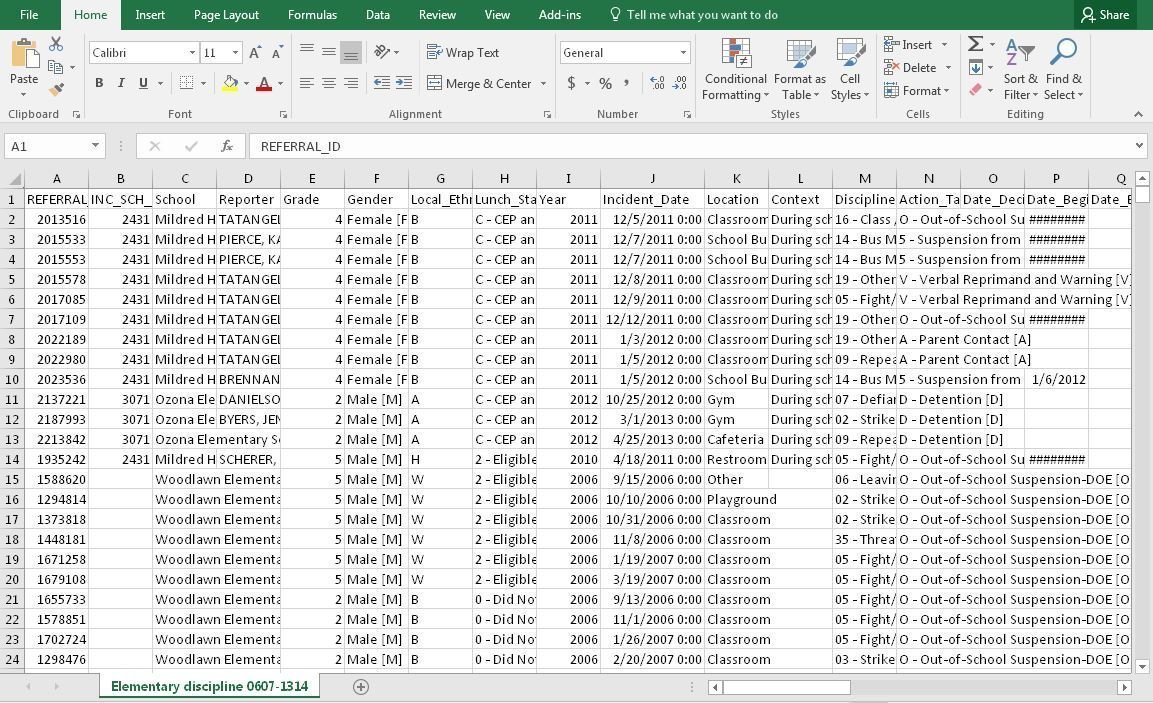

thinking through data requests

- Best to start with a simple question.

- How does the quality of teachers in these five schools compare to the quality of teachers in other schools?

- Simple. But too broad. To answer it, we need to break it down into separate things we can measure. What can we measure as indicators of teacher quality?

- Years' experience

- Years in the job

- Discipline history

- Then ask the question: what records or data will we need to look for trends in these areas?

4. telling the story

- There are two kinds of reporting.

- The kind you do to know you have a story.

- The kind you do to tell it well.

- Once you have locked down your authority by doing the data or records work, your job as a reporter is starting, not ending.

- If you try to tell a story using just numbers, your story is going to suck.

- Also, you need to be as skeptical of your data or records as you would be of any other single source.

- Go out and test the information by talking to as many real live people as you can.

being scientific about interviewing

- Think about what areas your story or stories are going to cover.

- Map out as many questions as you can, and then do two or three interviews to get a feel for how they will go.

- Let the subjects guide the interview, have a conversation.

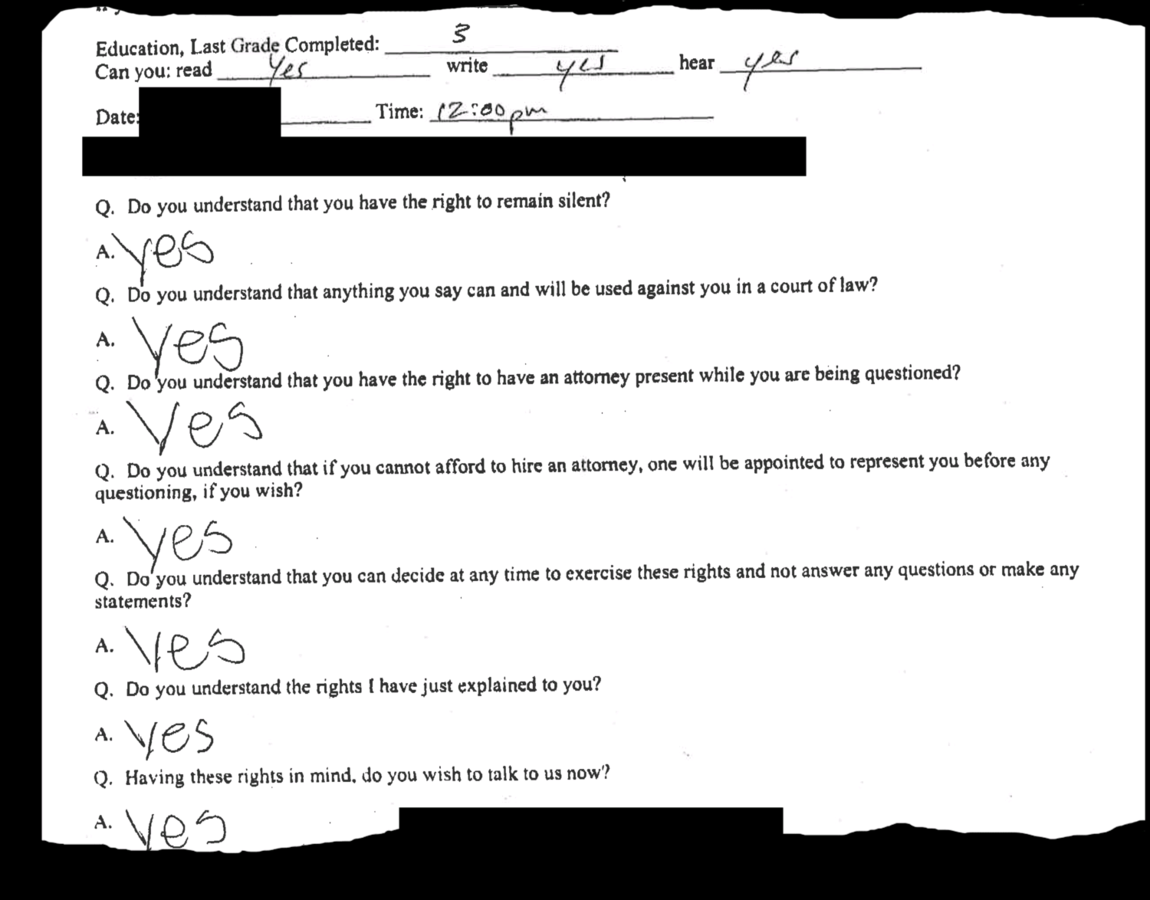

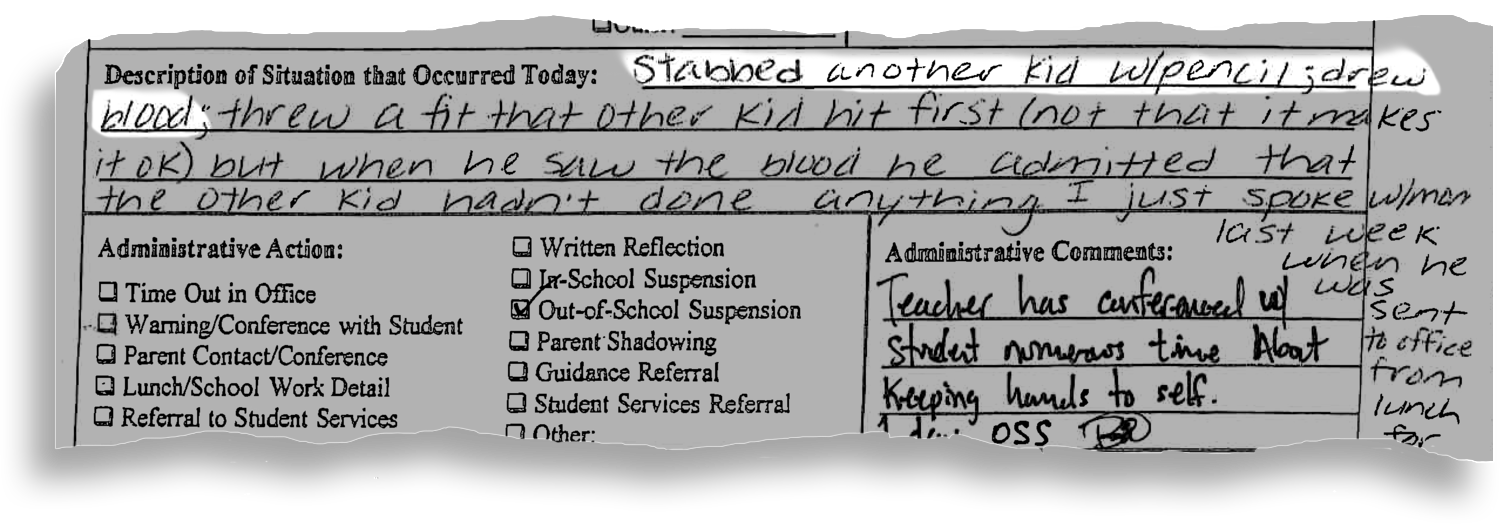

- It's not just about going door to door. Police reports are a handy tool for finding parents and kids to interview.

- After doing a few interviews, go over your answers and see what's missing.

- Did you talk about teacher quality but forget to ask about discipline?

- Did you talk about both but forget to ask about the child's grades?

- Did anything unexpected come up?

- Add questions you miss and ask them in all future interviews.

- Here's the questionnaire we ended up with after some trial and error.

Don't forget to ...

- Look over your interviews and ask yourself whether they are pointing to a trend or pattern you need to check out in your data -- or in data you haven't requested yet.

- If necessary, return to the data with new hypotheses, and test them.

5. writing investigative stories is hard

- The first five drafts of any investigative story are shit.

- We went through 40 drafts of part one alone.

- Early drafts that get discarded are not failures. They are reporting exercises.

- You're mastering your material, which means you're learning what you know and, more importantly, what you don't know and should.

- Early drafts almost always should lead to more reporting.

- A really strong nut graf, which lays out in no uncertain terms who the actor is and what the actor did or didn’t do that is leading to the problem your story is exposing. Bonus points if you can reveal what the actor’s motive is.

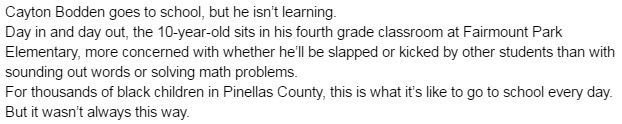

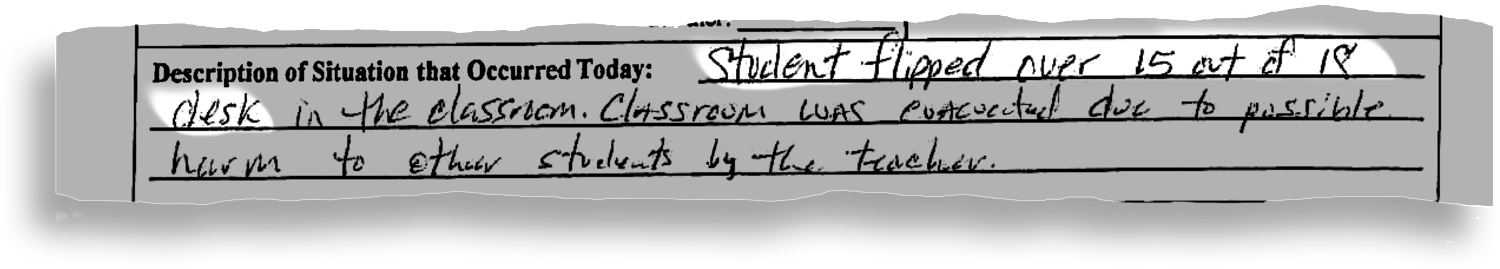

- A vivid case study. This focuses the problem on specifics and brings it to life in the reader’s mind.

- A scope section. That vivid example wasn’t the only case of this wrong thing happening. Not by a long shot. This describes how widespread the problem you’re dealing with is, using as many facts and figures as you can marshal to prove your point.

- Can be based in data or records (hundreds or thousands of examples) or anecdotal (at least a dozen cases, and here’s a sentence apiece on five of the most startling ones, so the reader gets the point that your case study isn’t an isolated incident).

- Other useful sections you can plug in and remove as you experiment with how your story flows:

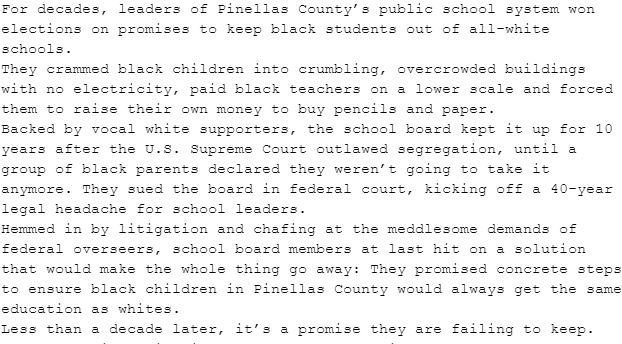

- Background section

- Blame section

- Focus directly on the specific actions the actor should or should not have taken to alleviate the problem and then lays out the specific ways the actor did the opposite.

- Kicker section.

rejected ledes for part one

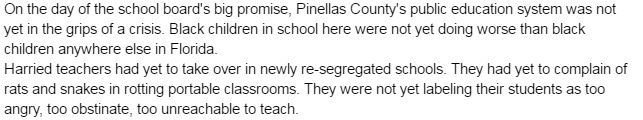

The Pinellas County School Board resegregated five schools in the county’s black neighborhoods, leaving them overwhelmingly poor and black, and then starved them of promised money and resources until they became some of the worst schools in the state.

6. bend over backwards to be fair

- If your subject opens your story and is surprised by what she reads, then you haven’t been fair enough.

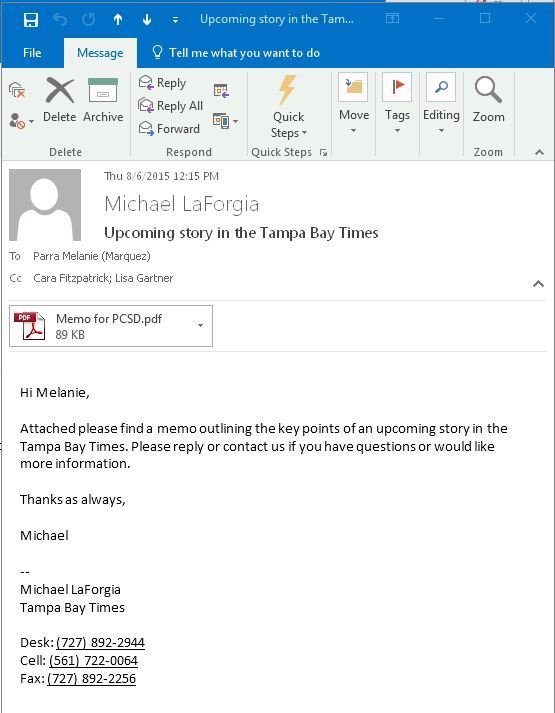

- We sent detailed memos to the school district ahead fo each story outlining all of our findings and asking them to respond.

- No surprises, and no mistakes.

Here's the memo we sent.

separate - and still unequal

By mlaforgia

separate - and still unequal

- 2,554