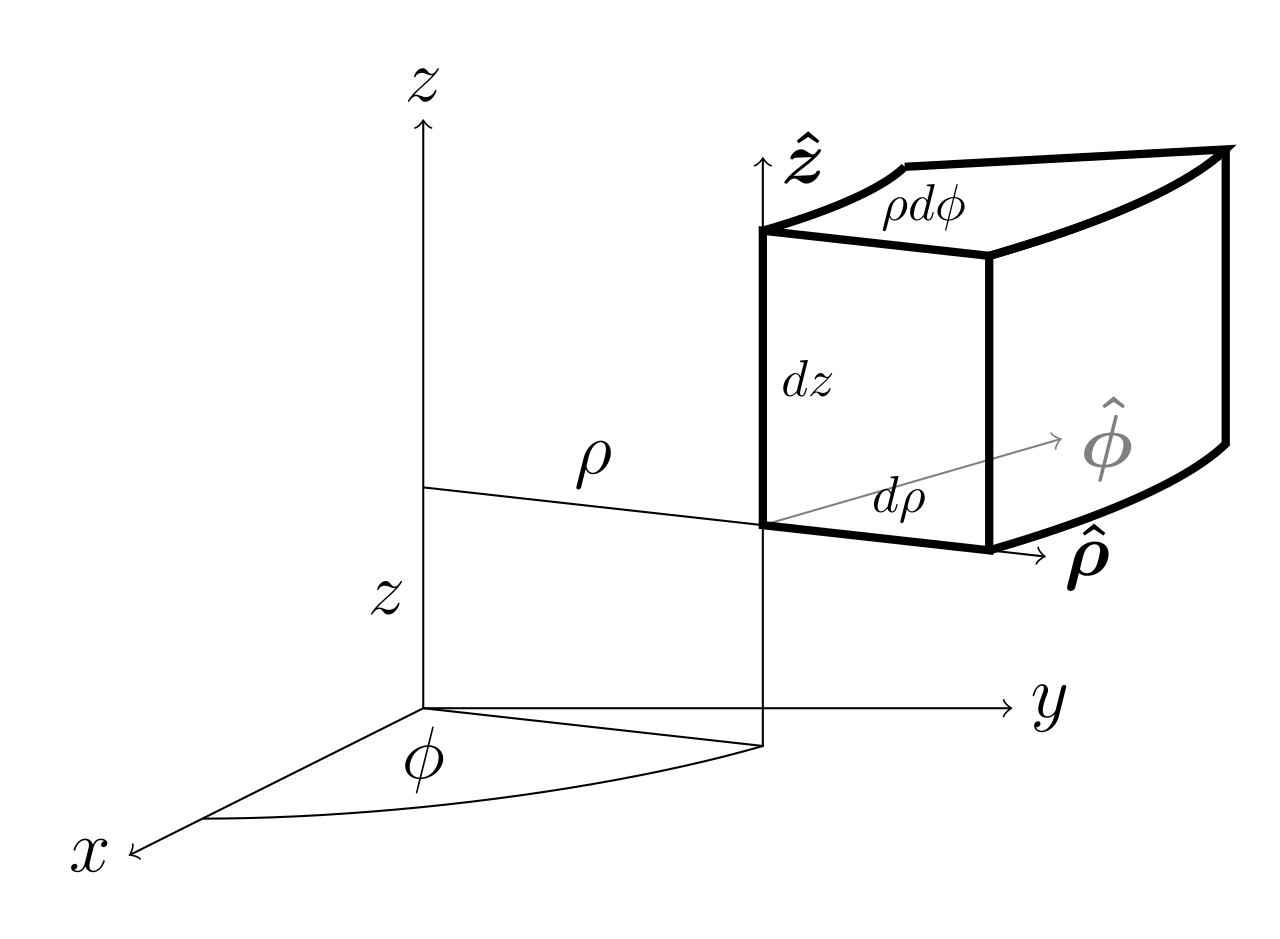

\text{Gradient, } \nabla

\text{in higer dimesions}

\text{let us define a vector quantity as follows:}

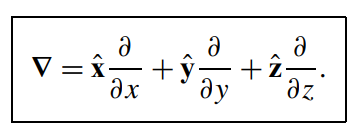

\text{We start first by defining the operator \textcolor{red}{Nabla } } \color{red}{\nabla}:

\text{The application of this \textcolor{orange}{operator} on a \textcolor{red}{scalar function} gives us:}

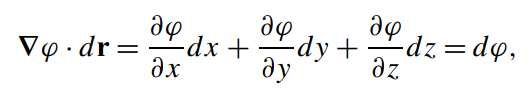

\displaystyle d\varphi(x,y,z)=\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x} dx+\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y} dy+\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z} dz

\text{To provide a motivation for the vector nature of partial derivatives, we }

\text{introduce the \textbf{the total variation of a function} }F(x,y)

\displaystyle d F=\frac{\partial F}{\partial x} dx+\frac{\partial F}{\partial y} dy

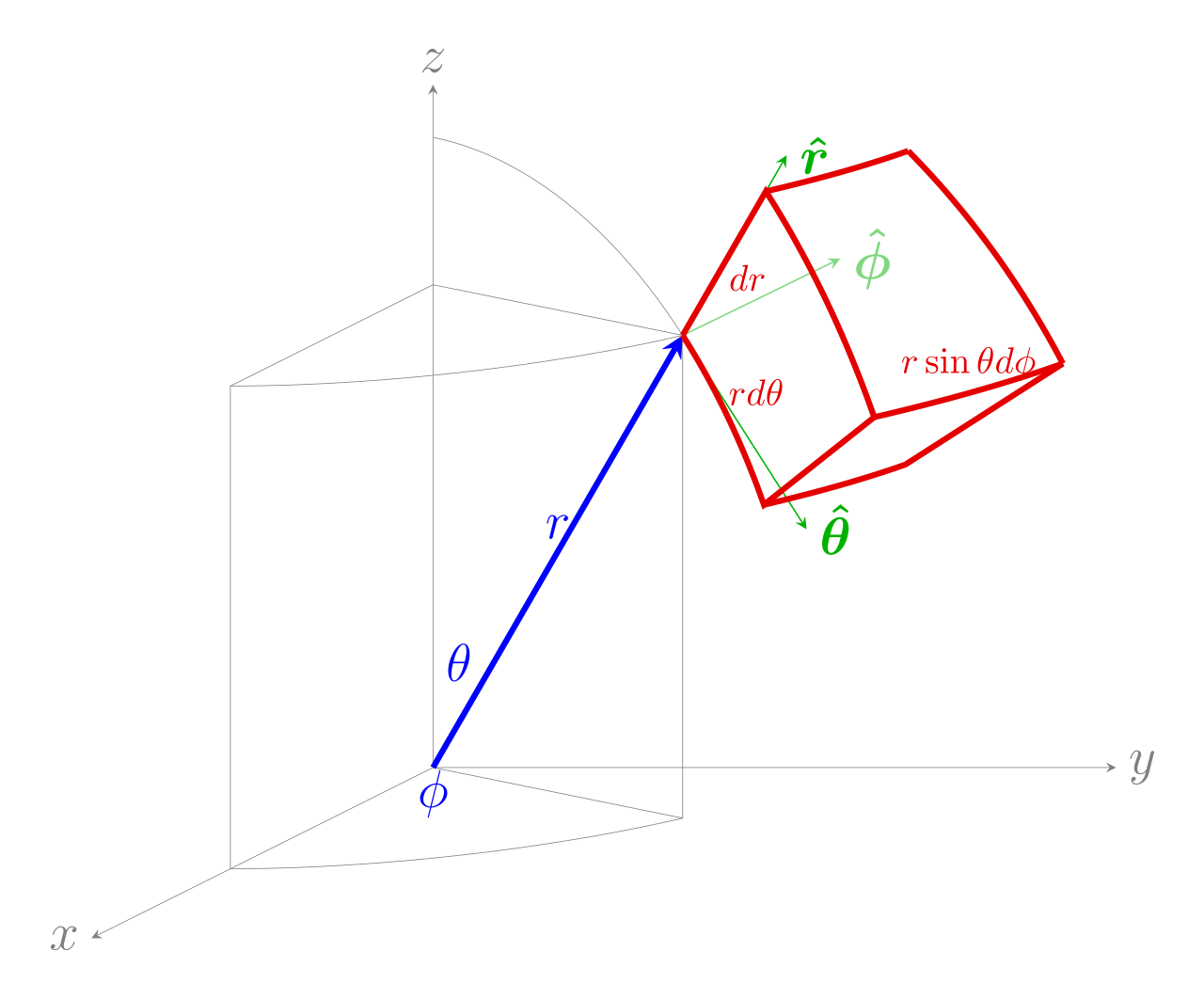

\Big(\displaystyle \frac{\partial }{\partial r}\hat{r} +\frac{\partial }{\partial z}\hat{z}+\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial}{\partial \varphi}\hat{\varphi} \Big)

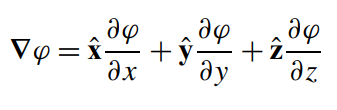

\Big(\displaystyle \frac{\partial }{\partial r}\hat{r} +\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial }{\partial \theta}\hat{\theta}+\frac{1}{r \sin\theta}\frac{\partial}{\partial \varphi}\hat{\varphi} \Big)

\text{Spherical coordinates}

\text{Cylindrical coordinates}

\text{with these definitions, the \textcolor{orange}{total variation} of a function can be expressed straightforwardly}

\text{Where}

\text{consider P and Q to be two points on a surface }\varphi(x,y,z)=C, \text{ a constant}

d\textbf{r}=\hat{\textbf{x}} dx+\hat{\textbf{y}} dy+\hat{\textbf{z}} dz

d\varphi=(\mathbf{\nabla}\varphi).d\mathbf{r}=0

\text{\textcolor{red}{Remark:} }

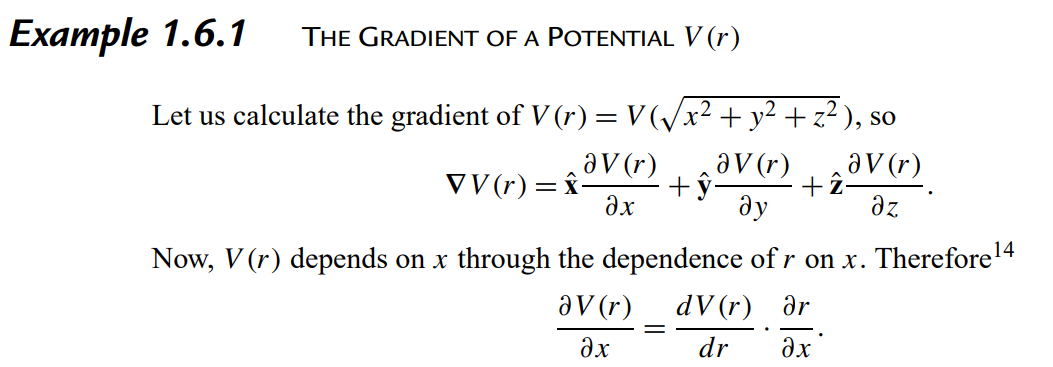

\text{This is valid for a potential } V(r) \text{ \textcolor{orange}{depending on r only }and not on the angles}

\displaystyle V(r)=-\frac{1}{r}

\text{Example:}

\displaystyle \nabla V(r)=\frac{1}{r^2} \hat{r}

\begin{aligned}

\nabla V(r) & =(\hat{\mathbf{x}} x+\hat{\mathbf{y}} y+\hat{\mathbf{z}} z) \frac{1}{r} \frac{d V}{d r} \\

& =\frac{\mathbf{r}}{r} \frac{d V}{d r}=\hat{\mathbf{r}} \frac{d V}{d r}

\end{aligned}

\text{Permuting the coordinates }(x\rightarrow y, y\rightarrow z,z\rightarrow x) \text{ to obtain } y \text{ and } z\text{ derivatives, we get}

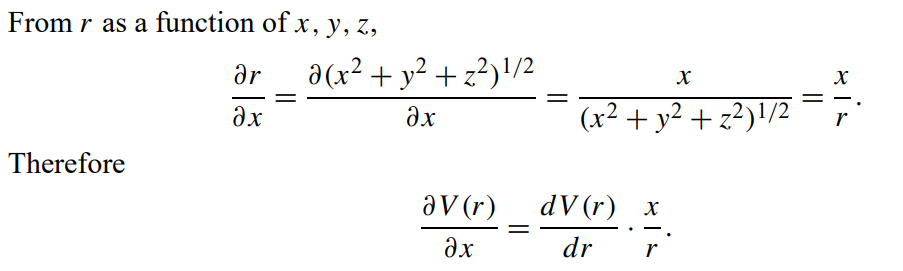

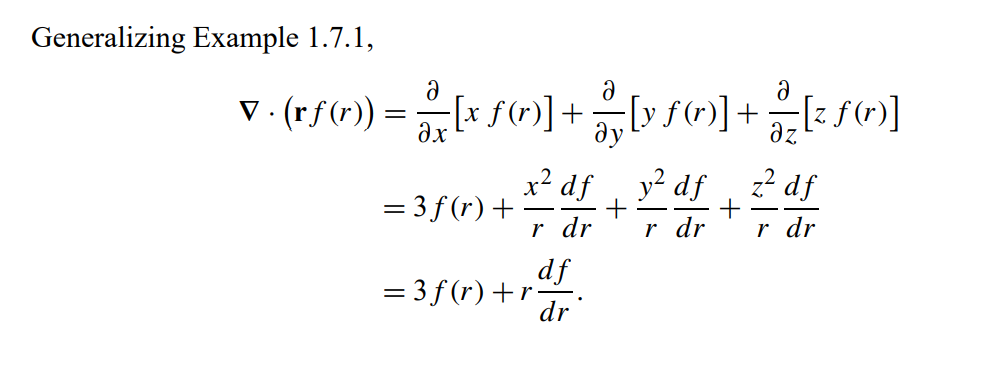

\text{Divergence}

\text{The application of the operator \textcolor{red}{Nabla ∇}on a \textcolor{green}{vector} will give you the divergence}

\displaystyle \nabla .\mathbf{V} =\frac{\partial V_x}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial V_y}{\partial y}+\frac{\partial V_z}{\partial z}

\begin{aligned}

\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \mathbf{r} & =\left(\hat{\mathbf{x}} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}+\hat{\mathbf{y}} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}+\hat{\mathbf{z}} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\right) \cdot(\hat{\mathbf{x}} x+\hat{\mathbf{y}} y+\hat{\mathbf{z}} z) \\

& =\frac{\partial x}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial y}{\partial y}+\frac{\partial z}{\partial z}

\end{aligned}

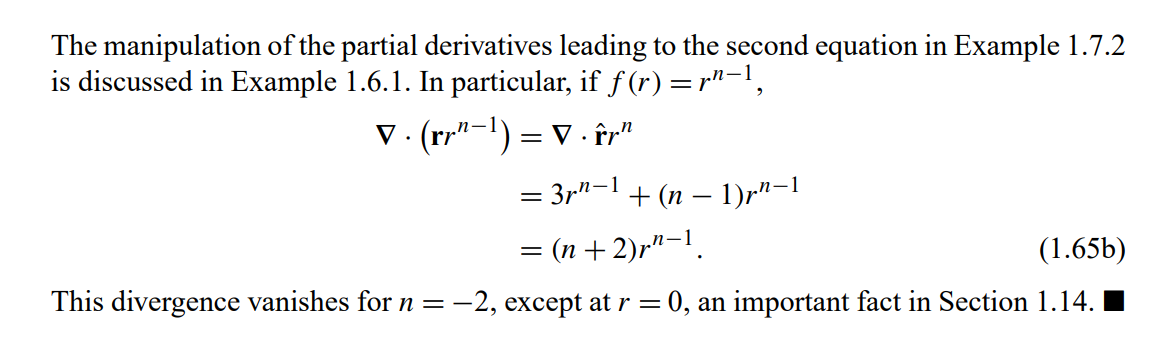

\text { \bf{Example 1.7.1}: \textcolor{red}{Divergence of Coordinate Vector }}

\text{Calculate $\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \mathbf{r}$ :}

\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \mathbf{r}=3.

\text{The combination $\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot(f \mathbf{V})$, in which $f$ is a scalar function and $\mathbf{V}$ is a vector function, may }

\text{be written}

\begin{aligned}

\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot(f \mathbf{V}) & =\frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(f V_x\right)+\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\left(f V_y\right)+\frac{\partial}{\partial z}\left(f V_z\right) \\

& =\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} V_x+f \frac{\partial V_x}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial f}{\partial y} V_y+f \frac{\partial V_y}{\partial y}+\frac{\partial f}{\partial z} V_z+f \frac{\partial V_z}{\partial z} \\

& =(\boldsymbol{\nabla} f) \cdot \mathbf{V}+f \boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \mathbf{V}

\end{aligned}

\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot(f \mathbf{V})=(\boldsymbol{\nabla} f) \cdot \mathbf{V}+f \boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \mathbf{V}

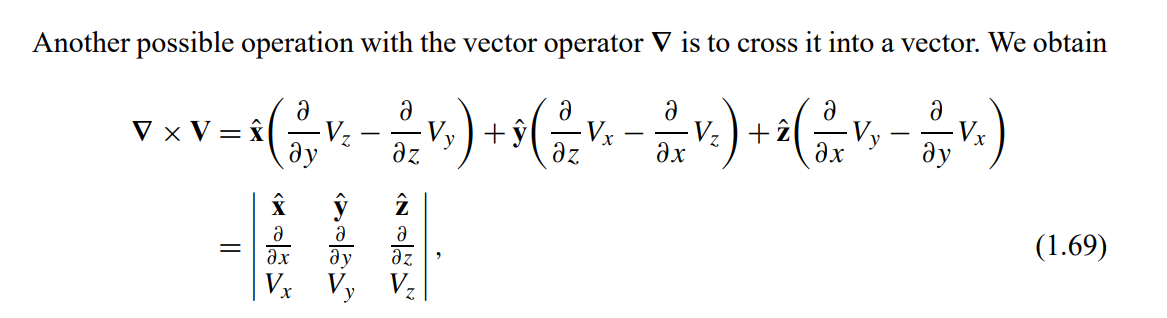

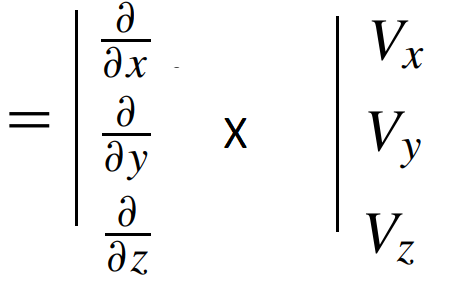

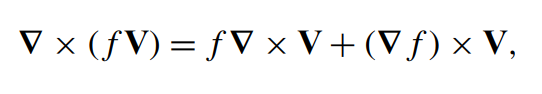

\text{Curl,} \nabla \times

\text{Solution:}

\text{Prove that:}

\text{Suppose that the force is: } \displaystyle \bold{F}(\bold{r})=\bold{\hat{r}} f(r)\\

\text{We used the fact that } \hat{r}\times \hat{r}=0 \text{ and the fact that f(r) } \text{doesn't depend on } \theta \text{ or } \varphi\\

\text{\textcolor{red}{Question:} Find the Curl for a radial force.}

\text{Hint: use equation 1.71 or any other method}

\text{In the spherical coordinates, we can write:}\\

\Big(\displaystyle \frac{\partial }{\partial r}\hat{r} +\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial }{\partial \theta}\hat{\theta}+\frac{1}{r \sin\theta}\frac{\partial}{\partial \varphi}\hat{\varphi} \Big)

\times \hat{r} f(r)=0

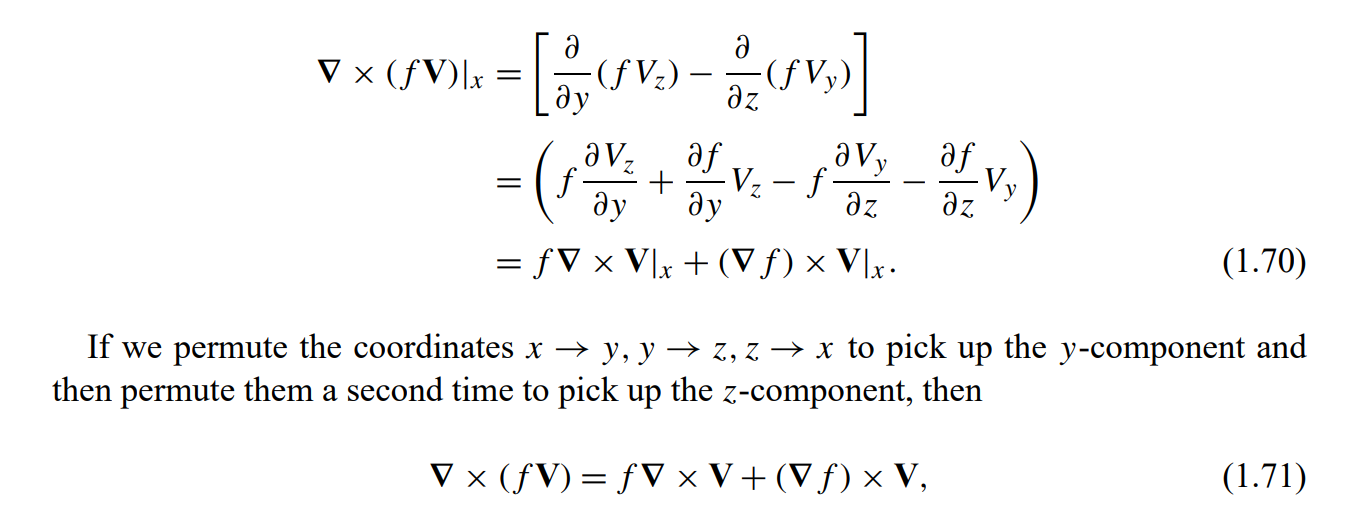

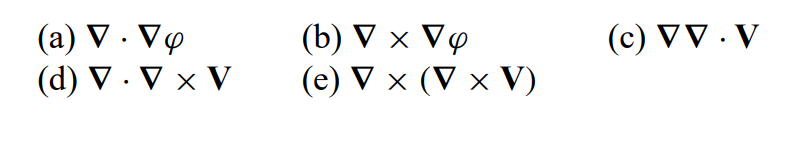

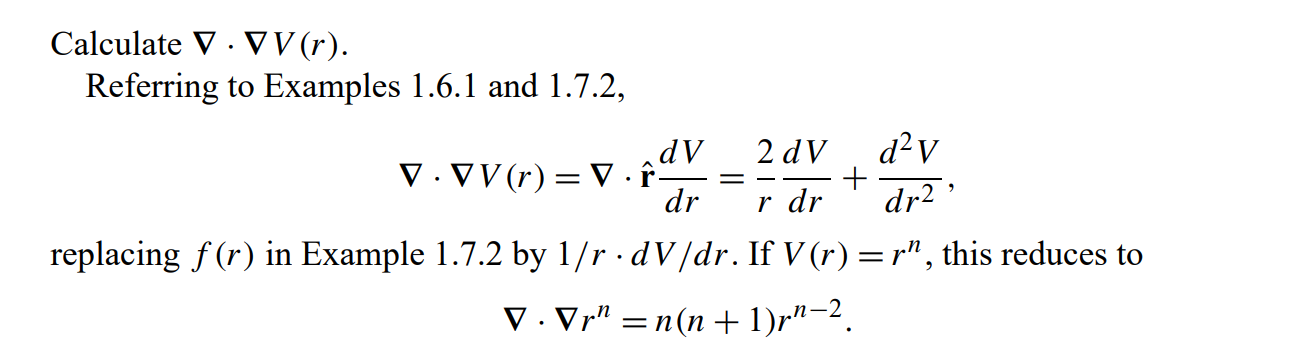

\text{SUCCESSIVE APPLICATIONS OF }\nabla

\text{a) Laplacian}

b)

\begin{aligned}

\nabla \times \nabla \varphi= & \hat{\mathbf{x}}\left(\frac{\partial^2 \varphi}{\partial y \partial z}-\frac{\partial^2 \varphi}{\partial z \partial y}\right)+\hat{\mathbf{y}}\left(\frac{\partial^2 \varphi}{\partial z \partial x}-\frac{\partial^2 \varphi}{\partial x \partial z}\right) \\

& +\hat{\mathbf{z}}\left(\frac{\partial^2 \varphi}{\partial x \partial y}-\frac{\partial^2 \varphi}{\partial y \partial x}\right)=0,

\end{aligned}

\begin{aligned}

\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla} \varphi & =\left(\hat{\mathbf{x}} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}+\hat{\mathbf{y}} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}+\hat{\mathbf{z}} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\right) \cdot\left(\hat{\mathbf{x}} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\hat{\mathbf{y}} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\hat{\mathbf{z}} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\right) \\

& =\frac{\partial^2 \varphi}{\partial x^2}+\frac{\partial^2 \varphi}{\partial y^2}+\frac{\partial^2 \varphi}{\partial z^2}

\end{aligned}

\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla} \times \mathbf{V}=0

\boldsymbol{\nabla} \times(\boldsymbol{\nabla} \times \mathbf{V})=\nabla \nabla \cdot \mathbf{V}-\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla} \mathbf{V},

\text{Useful relations:}

\text{Non trivial calculation rules:}

\begin{aligned}

& \operatorname{div} \operatorname{grad} f \equiv \nabla \cdot \nabla f \equiv \nabla^2 f \\

& \operatorname{curl} \operatorname{grad} f \equiv \nabla \times \nabla f=\mathbf{0} \\

& \operatorname{div} \operatorname{curl} \mathbf{A} \equiv \nabla \cdot(\nabla \times \mathbf{A})=0 \\

& \operatorname{curl} \operatorname{curl} \mathbf{A} \equiv \nabla \times(\nabla \times \mathbf{A})=\nabla(\nabla \cdot \mathbf{A})-\nabla^2 \mathbf{A} \\

& \nabla^2(f g)=f \nabla^2 g+2 \nabla f \cdot \nabla g+g \nabla^2 f

\end{aligned}

\text{Magnetic field and gauge transformation}

\text{The solution to the homogenious Maxwell equations are}

\text{The solution is not unique: if we do the transformation}

\text{However, the electric field becomes}

\text{That is why, we conclude that the additional transformation}

\text{Will leave both E and B unchanged}

\text{A particular choice of the scalar and vector potentials is a gauge }

\displaystyle \varphi\rightarrow\varphi-\frac{\partial \psi}{\partial t}

\displaystyle \mathbf{E}=-\nabla\varphi-\frac{\partial \mathbf{A}}{\partial t}, \hspace{5mm}\mathbf{B}=\nabla\times \mathbf{A}

\mathbf{A}\rightarrow\mathbf{A}+\nabla\psi

\text{B remains the same because }\nabla\times\nabla \psi=0

\mathbf{B}=\nabla\times(\mathbf{A}+\nabla \psi)=\nabla\times \mathbf{A}

\displaystyle \mathbf{E}=-\nabla\Big(\varphi+\frac{\partial \psi}{\partial t}\Big)-\frac{\partial \mathbf{A}}{\partial t}

\displaystyle \partial V \text{ is the closed surface englobing the volume }V

\text{Let } \bold{V} \text{ be the vector representing the electric field } \bold{E}(x,y,z)\\

\text{From Maxwell equations, we have } \displaystyle \nabla \bold{E}=\frac{\rho}{\epsilon_0}

\text{We deduce at the end that} \displaystyle \iint_{\partial V} \bold{E} d\bm{ \sigma}=\frac{Q_{\text{enclosed}}}{\epsilon_0}

\text{This is the Gauss Law we studied in phys 102}

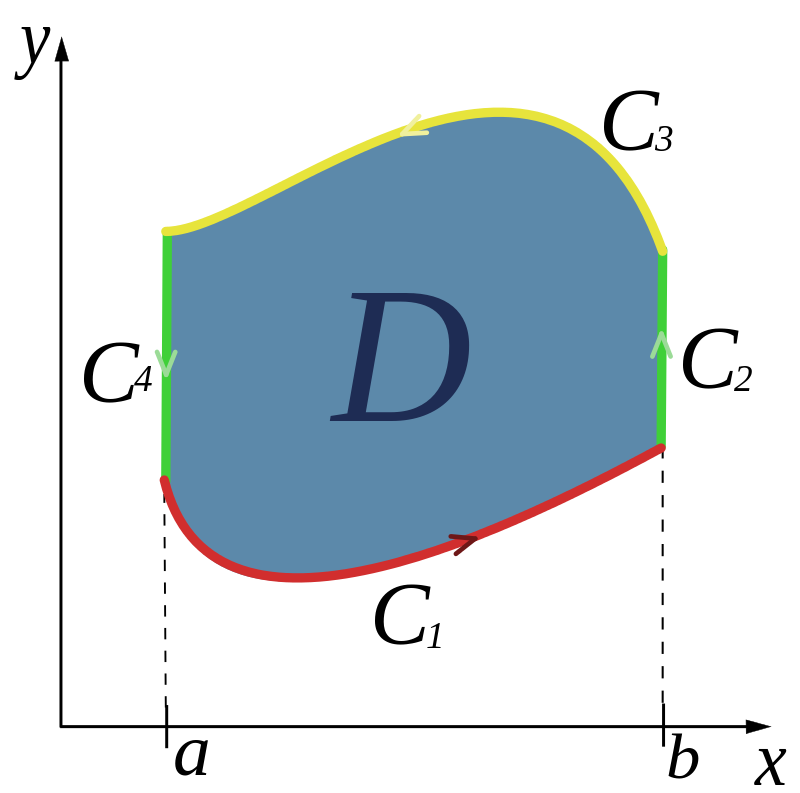

\text{Example 1:}

\text{It relies the flux of a vector field through a closed surface to the divergence}

\text{of the field in the \textcolor{red}{closed }volume}

\text{Gauss-Ostrogradski theorem}

\displaystyle \iint_{\partial V} \bold{E} \hspace{1mm} d\bm{ \sigma}=\iiint_V \nabla \bold{E }\hspace{1mm} dV

\displaystyle \oiint_{\partial V} \bold{V} .\hspace{1mm}d \bm{\sigma}=\iiint_V \nabla .\mathbf{V} d\tau

\text{(Divergence theorem)}

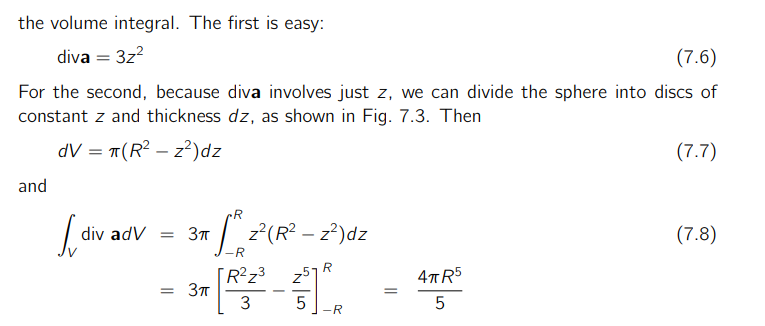

\displaystyle \int_C \overrightarrow {F} d\vec{r}=\iint_D (\vec{\nabla} \times \vec{F}) d\vec{A}

\text{Green's theorem}

\text{It relies the line integral of a vector over a closed curve to the integral of}

\text{the curl of the vector over the area of the curve domain}

\text{another form of this reads:}

\text{The \textcolor{red}{line C }is defined \textcolor{red}{anticlockwise}}

\displaystyle

\oint_c (P dx+Qdy)=\iint_D \Big(\frac{\partial P}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial Q}{\partial y}\Big)dx dy

\text{Solve $\oint_c y^3 d x-x^3 d y$ where C is a circle of radius 2 centered in origin.}

\text{Question:}

\text{Solve $\oint_c y^3 d x-x^3 d y$ where C is a circle of radius 2 centered in origin.}

\text{Question:}

\text{Identify $P$ and $Q$ from the line integral. Here, $P=y^3$ and $Q=-x^3$}

\begin{aligned}

& \oint_C y^3 d x-x^3 d y=\iint_D-3 x^2-3 y^2 d A \\

& =-3 \int_0^{2 \pi} \int_0^2 r^3 d r d \theta \\

& =-3 \int_0^{2 \pi} \frac{1}{4}\left[r^4\right]_0^2 d \theta \\

& =-3 \int_0^{2 \pi} 4 d \theta =-24 \pi

\end{aligned}

\text { Therefore, } \oint_c y^3 d x-x^3 d y=-24 \pi

\text{Stokes's theorem}

\text{Stokes theorem is the generalization of the Green's theorem to 3D}

\text{In other words, if you take the 3-dimensional formulation of Stokes' theorem}

\displaystyle \oint_{\partial \Sigma}\Big(F_x dx+F_y dy+F_z dz\Big)=

=\displaystyle \iint_\Sigma\bigg( \frac{\partial F_z}{\partial y}-\frac{\partial F_y}{\partial z}\bigg)dy dz+

\bigg( \frac{\partial F_x}{\partial z}-\frac{\partial F_z}{\partial x}\bigg)dz dx+

\bigg( \frac{\partial F_y}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial F_x}{\partial y}\bigg)dx dy

\text{and set, let's say, } F_z=0 \text{ and }dz=0. \text{The whole thing simplifies to}

\displaystyle \oint_{\partial \Sigma}\Big(F_x dx+F_y dy\Big)=\displaystyle \iint_\Sigma\bigg( \frac{\partial F_y}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial F_x}{\partial y}\bigg)dx dy

\text{Which is exactly the statement of the Green's theorem}

\displaystyle \oint \mathbf{V} \cdot d \bm{\lambda}=\int_S \nabla \times \mathbf{V} \cdot d \bm{\sigma}

\text{Problems:}

\displaystyle \oiint_S d \bm{\sigma}=0

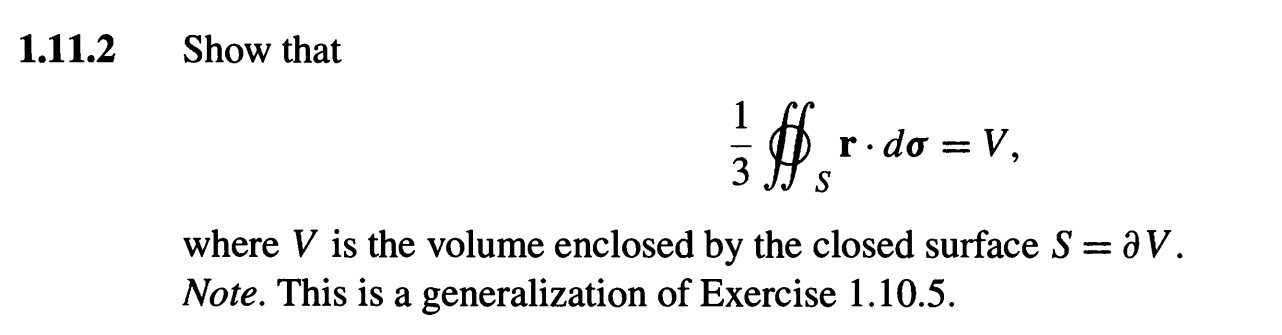

\text{Using Gauss' theorem, prove that}

\text{if } S=\partial V, \text{ is a closed surface}

1.11.1

\oiint_S \mathbf{B} \cdot d \boldsymbol{\sigma}=\mathbf{0}

\text { for any closed surface } S \text {. }

\text { 1.11.3 \hspace{2cm} If } \mathbf{B}=\nabla \times \mathbf{A} \text {, show that }

% requires \usepackage{xcolor} % for colored words

% (optional) \usepackage{esint} % for \oiint (closed surface integral). Otherwise use \iint.

\begin{align*}

& \text{Suppose we wish to evaluate }\\

& \hspace{3cm} \iint_{S} \mathbf{F}\!\cdot\!\mathbf{n}\, dS, \\[0.4em]

& \text{where } S \text{ is the } \textcolor{blue}{\text{unit sphere}} \text{ defined by }\\

& \qquad S=\{(x,y,z)\in \mathbb{R}^{3} : x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}=1\},\\[0.4em]

& \text{and } \mathbf{F} \text{ is the } \textcolor{blue}{\text{vector field}} \\[0.2em]

& \qquad \mathbf{F}=2x\,\mathbf{i} + y^{2}\,\mathbf{j} + z^{2}\,\mathbf{k}.

\end{align*}

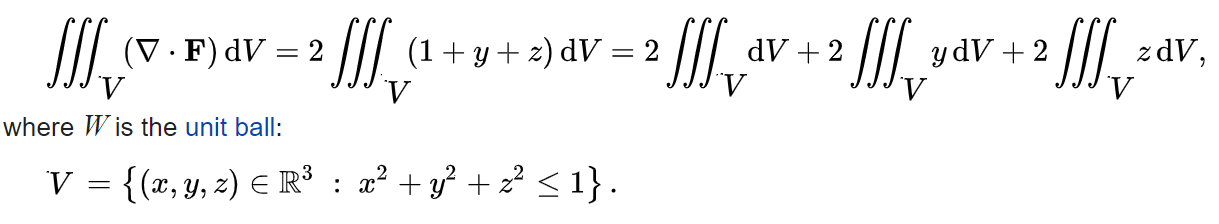

\text{Using the Gauss-Ostrogradsky theorem, we get}

\iiint_V y \mathrm{~d} V=\iiint_V z \mathrm{~d} V=0

\text { because the unit ball } V \text { has volume } \frac{4 \pi}{3} \text {. }

\oiint_S \mathbf{F} \cdot \mathbf{n} \mathrm{~d} S=2 \iiint_W d V=\frac{8 \pi}{3}

\text{Therfore,}

\begin{align*}

& \textit{1.12.1}\ \ \text{Given a vector } \mathbf{t}=-\hat{\mathbf{x}}\,y+\hat{\mathbf{y}}\,x, \text{ show, with the help of Stokes' theorem,}\\

& \text{that the integral around a continuous closed curve in the $xy$-plane}\\[0.3em]

& \hspace{3cm}\frac{1}{2}\oint \mathbf{t}\cdot d\boldsymbol{\lambda}

\;=\; \frac{1}{2}\oint \bigl(x\,dy-y\,dx\bigr)\;=\;A,\\[0.3em]

& \text{the area enclosed by the curve.}

\end{align*}

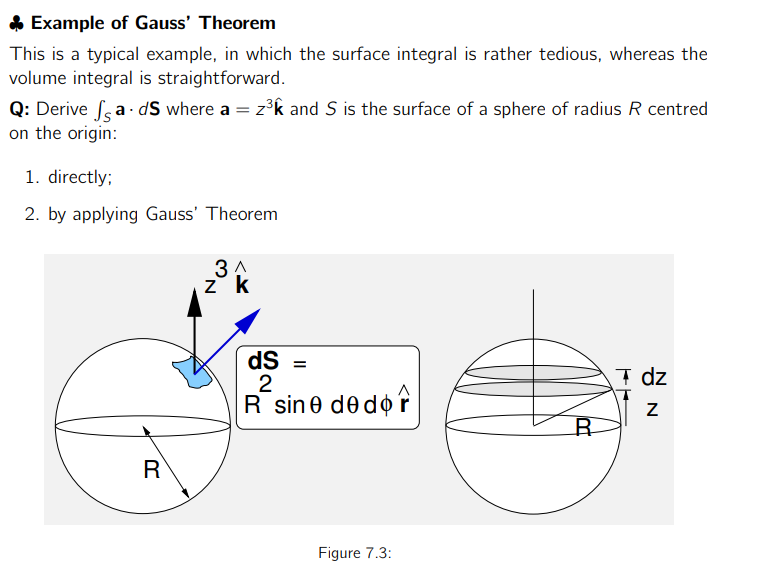

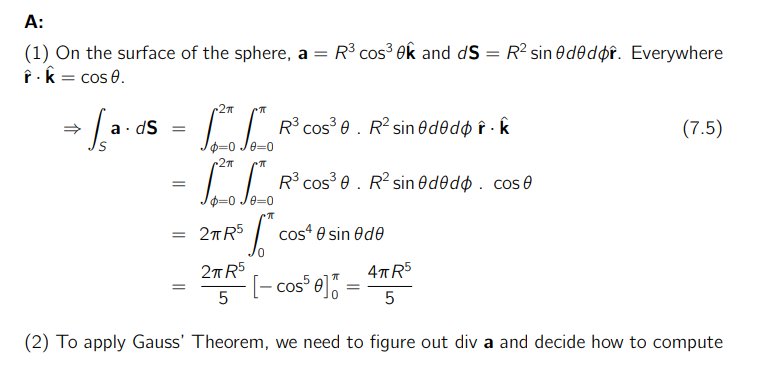

\text{Calculate the following integral over the surface S: } \displaystyle \iint_S \vec{a} \hspace{1mm}d\vec{S}

\text{S is the surface of a sphere of radius R. } \vec{a}=z^3 \hat{z}.\\

Gauss and Green theorems

By smstry

Gauss and Green theorems

- 379