Applied Microeconomics

Lecture 1

BE 502

Economics

The dismal science

The study of how scarce resources are allocated among competing ends.

Economics

This is applied economics – learn how to apply thinking like an economist to different situations.

Let's start with an example.

The National Raisin Reserve

US government determines a price for raisins each year

- To meet that price, there is a limit on how many raisins can be sold.

- Remaining raisins are seized by the government – in 2003, they took 47% of every farmer’s raisin crop without payment for the Raisin Reserve.

It is illegal to sell more of your share of raisins!

The National Raisin Reserve

Who does this program help?

Who does this program hurt?

Some farmers switched to growing other crops like almonds. Why would they do that?

The National Raisin Reserve

Meet Marvin Horne:

“The hell with the whole mess,” he says now. “It’s like being a serf.” (Washington Post, 2013)

The National Raisin Reserve

Was it fair for Marvin to sell his raisins?

Good News for Marvin!

Thinking critically in economics

We can make predictions about what might happen in a market -- like the market for raisins-- by making assumptions about what the players in that market want and how the market will react.

We assume Marvin behaved that way because he wanted to make more money from his raisin crop.

Consumers want raisins at a lower price.

Raisin farmers want a higher price.

Flooding the raisin market will lower the price.

Models in Economics

Economists use

models to describe the world around us.

A model is a simplified view of reality. It abstracts away from details and makes assumptions.

A simple model is often enough to reach the correct conclusion.

Sometimes we need quantitative data and numbers

- How much are farmers hurt by program?

- What is the price of raisins in a free market?

- Measuring fairness or well-being

Consumer Demand

THe Be 502 Store

-

Imagine you have a total income of $5 to spend on these four products.

-

You can buy as much of the products (or none), but you must spend all $5.

-

http://tinyurl.com/Store502/

A Peanut Shortage!

-

Week 2: Due to a peanut shortage, the price of Snickers has gone up to $2.

- You still have $5 to spend this week.

-

You can buy as much of the products (or none), but you must spend all $5.

- http://tinyurl.com/Store502/

I'm In the Money!

Consumer Demand

We think of an individual consumer's demand for a product as a function of many things:

Qd=f(Price, ... )

What determines the quantity of a product that consumers want to buy?

Consumer Demand

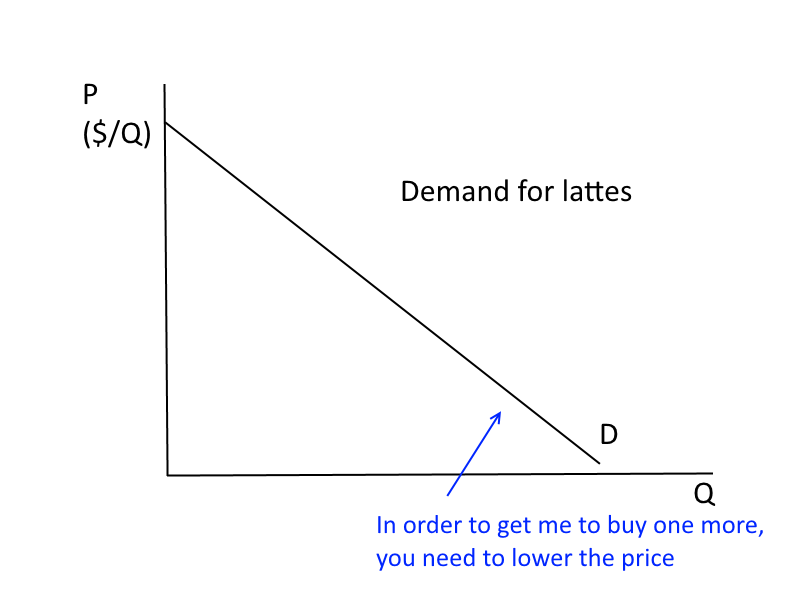

A consumer's demand curve shows the quantities that an individual is willing to buy at every possible price holding everything else constant (ceteris paribus).

If something that affects demand other than price changes, the demand curve will shift.

Demand

There are three "levels" of demand for a product:

- Individual demand: how much of a product an individual would like to buy at any given price.

- Market demand: total quantity of a product that can be sold in the market at any given price.

- Firm-level demand: the demand faced by a single firm.

Consumer Demand

A simple example: the market for lattes at UM

"need... caffeine..."

Consumer Demand

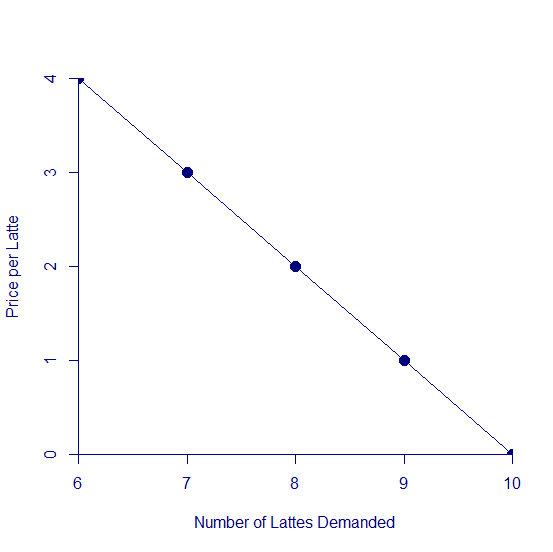

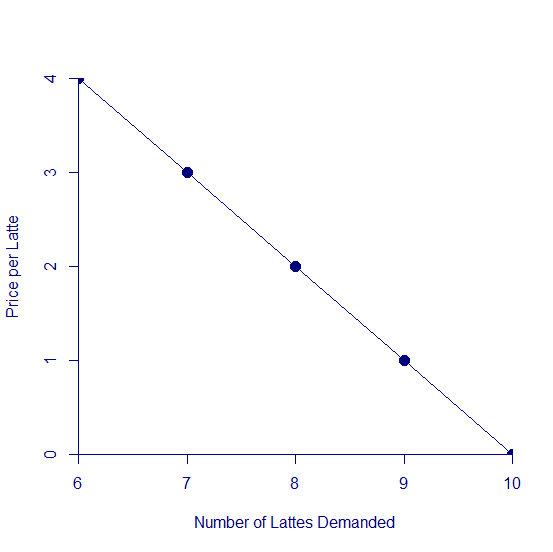

My Demand for Lattes

If the price is.... I would like to buy (in a week)...

- Free lattes!...10 lattes

- $1 per latte... 9 lattes

- $2 per latte... 8 lattes

- $3 per latte... 7 lattes

- $4 per latte... 6 lattes

Consumer Demand

Consumer demand (quantity) is a function of price.

Qd=f(P).

But, we always graph an inverse demand curve where P is on the y axis.

Consumer Demand

My Demand for Lattes

- Free lattes!...10 lattes

- $1 per latte... 9 lattes

- $2 per latte... 8 lattes

- $3 per latte... 7 lattes

- $4 per latte... 6 lattes

Does demand have to be linear?

Consumer Demand

If I always buy 7 lattes per week no matter the price, what does my demand look like?

- We characterize the inverse demand function as the amount a consumer is "willing and able to pay" for a certain quantity of the good.

Consumer Demand

Law of Demand: the observation that, ceteris paribus, the quantity demanded of a good falls when the price of the good rises.

Why? Are there any goods that do not behave this way?

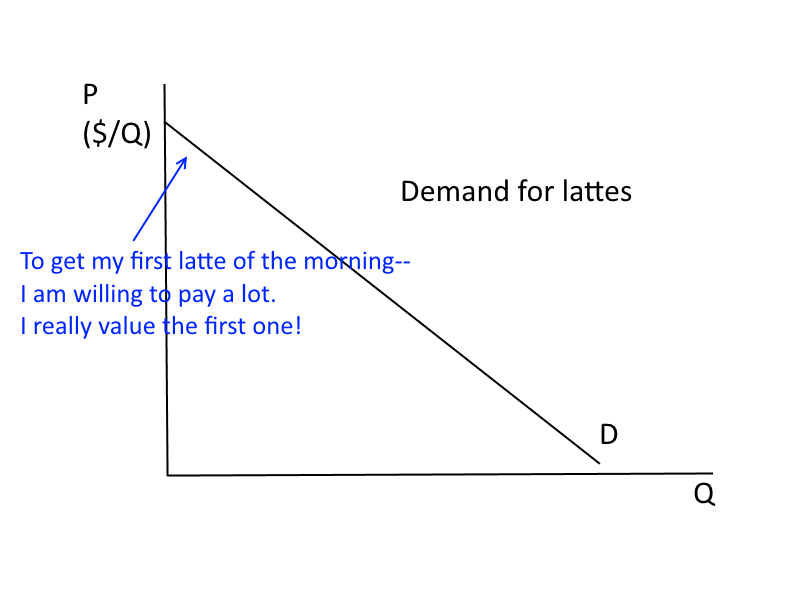

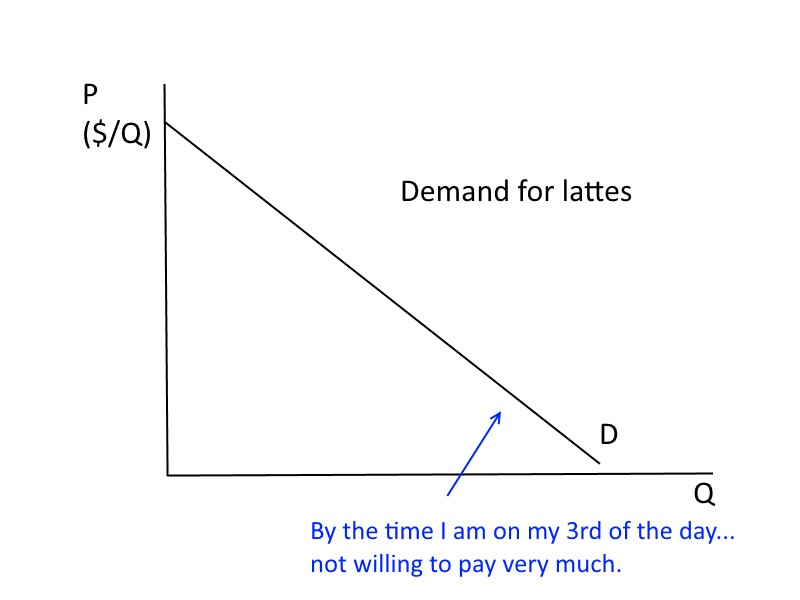

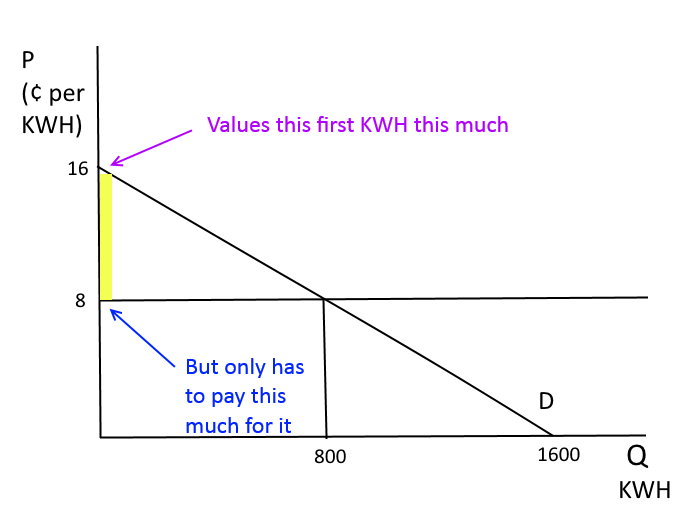

Consumer Demand

Thinking on the margin is an important recurring theme in this class.

I will buy lattes until the price of the next latte is above my willingness to pay.

Willingness to pay is one way we measure how much a consumer "values" a good--how much will he be willing to give up to get the good?

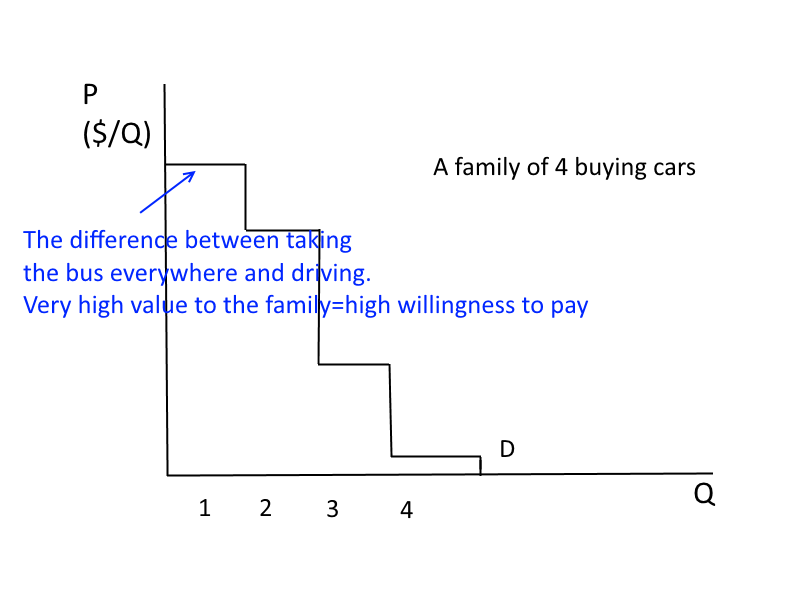

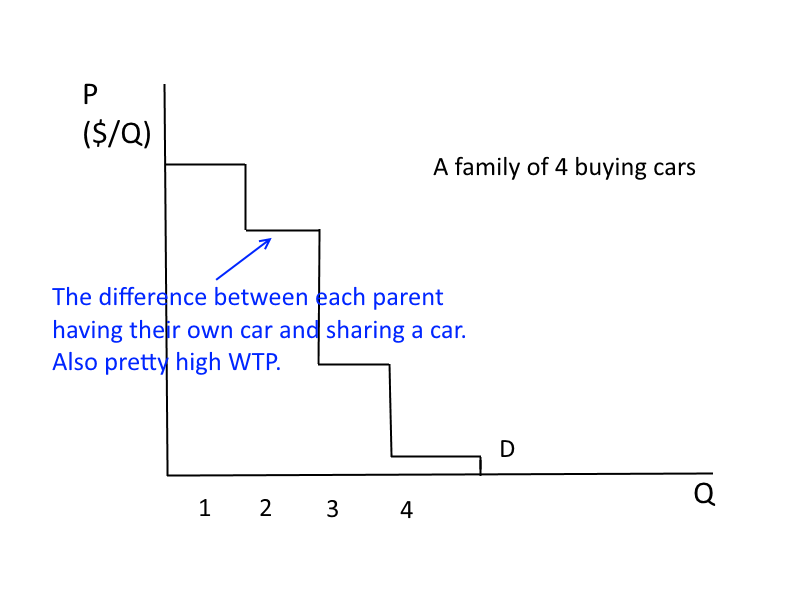

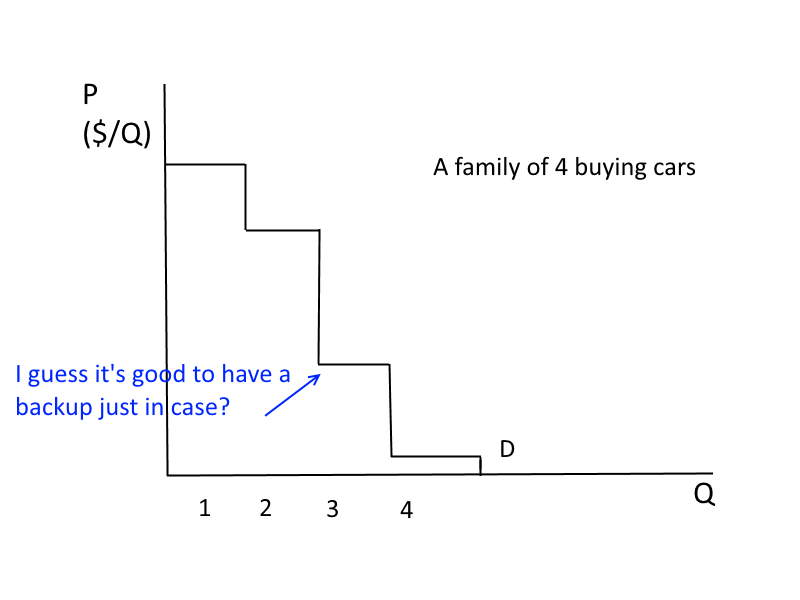

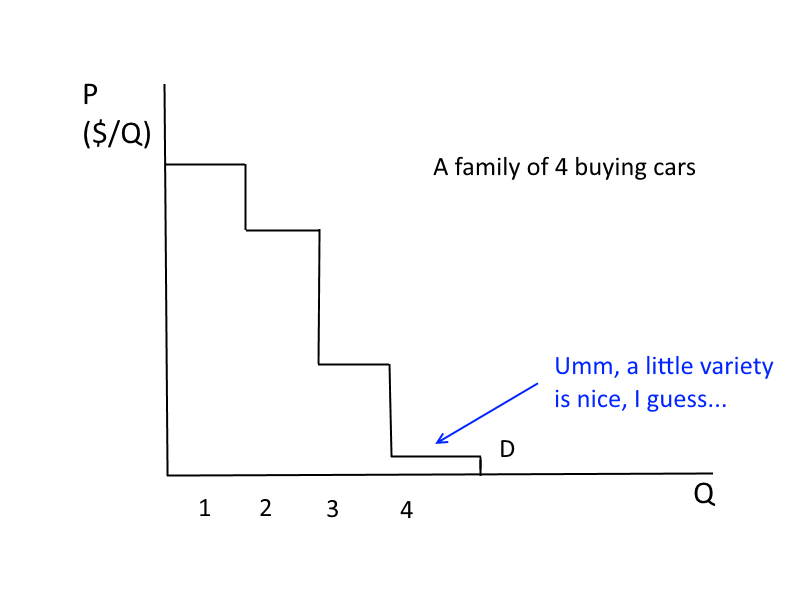

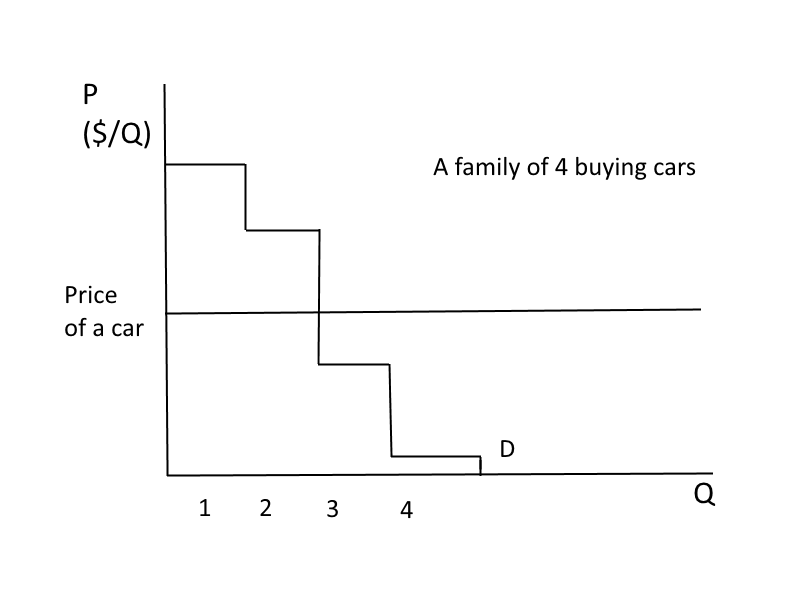

Willingness to Pay

Willingness to Pay

Willingness to Pay

Willingness to Pay

Willingness to Pay

Willingness to Pay

Willingness to Pay

Willingness to Pay

Willingness to Pay

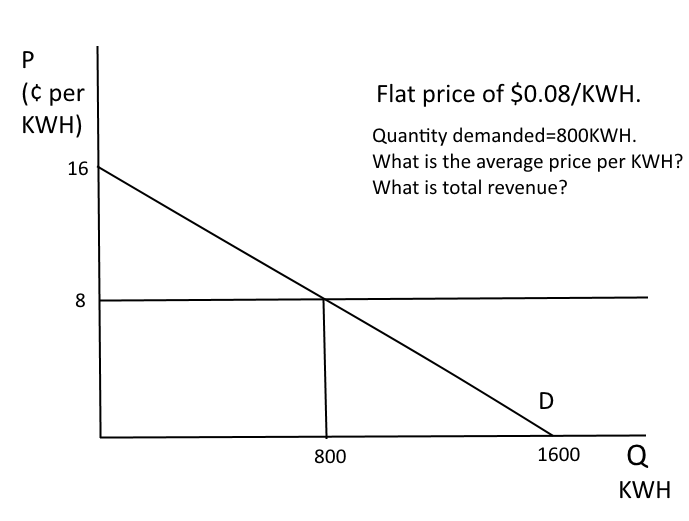

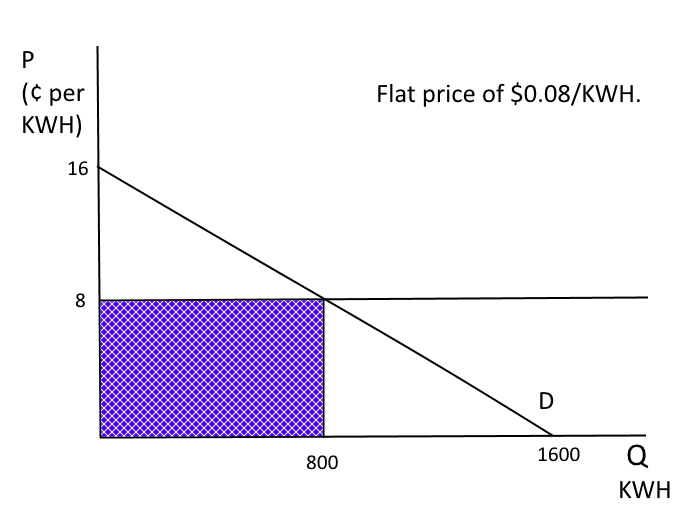

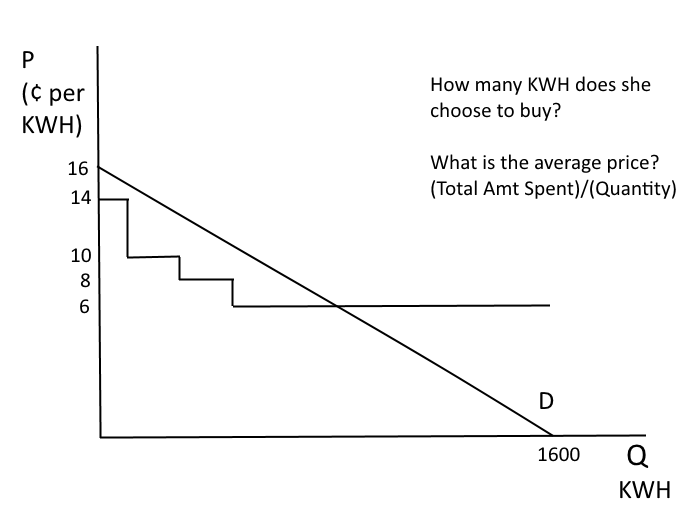

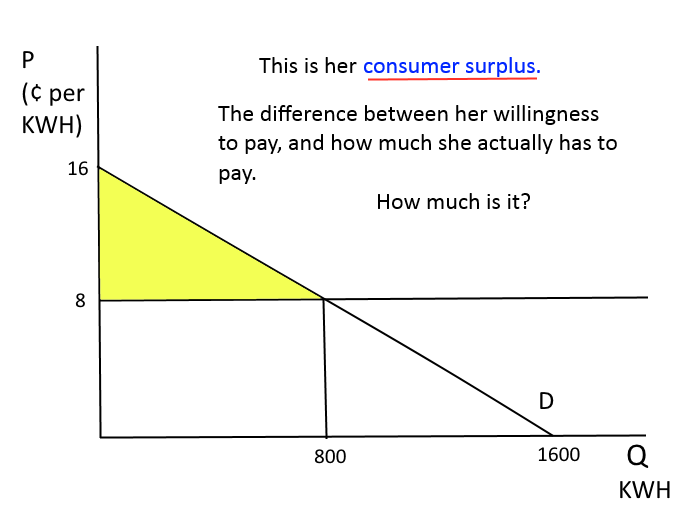

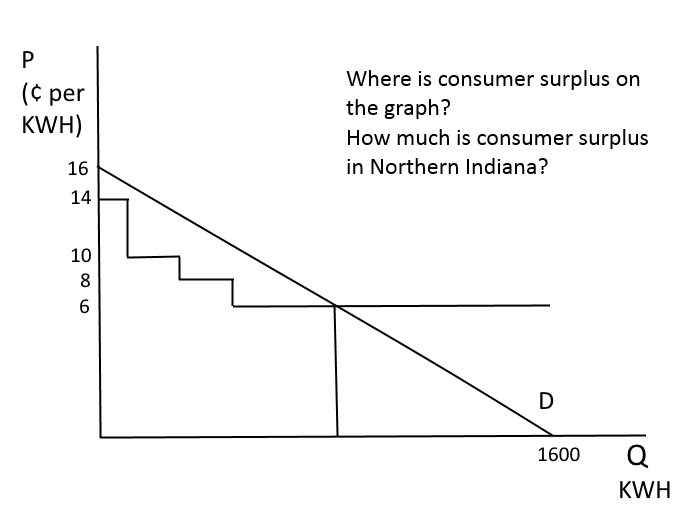

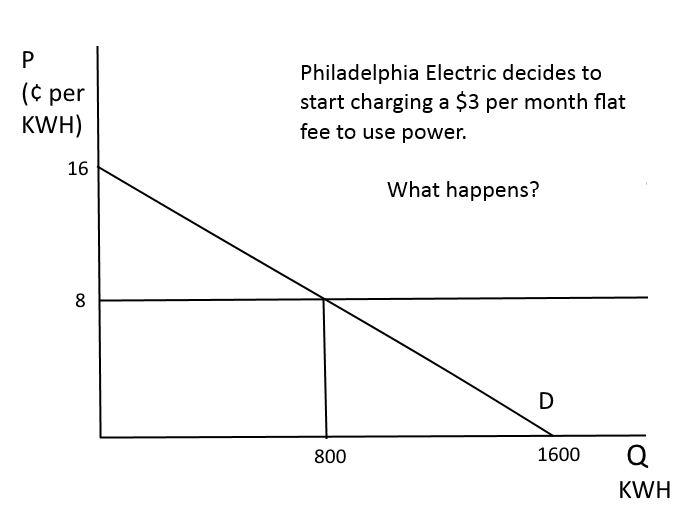

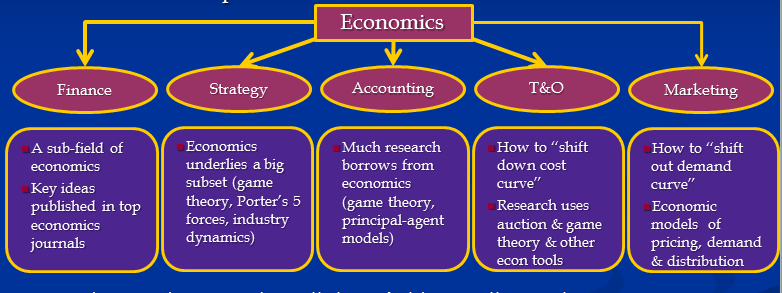

Electrical Power Purchasing

Electrical Power Purchasing

Individual demand curve: Q=1600-100P.

How do we plot this? (y-intercept?)

Remember--we graph price on the y-axis!

Inverse Demand: P = 16 – 0.01Q

Electrical Power Purchasing

Electrical Power Purchasing

Electrical Power Purchasing

Electrical Power Purchasing

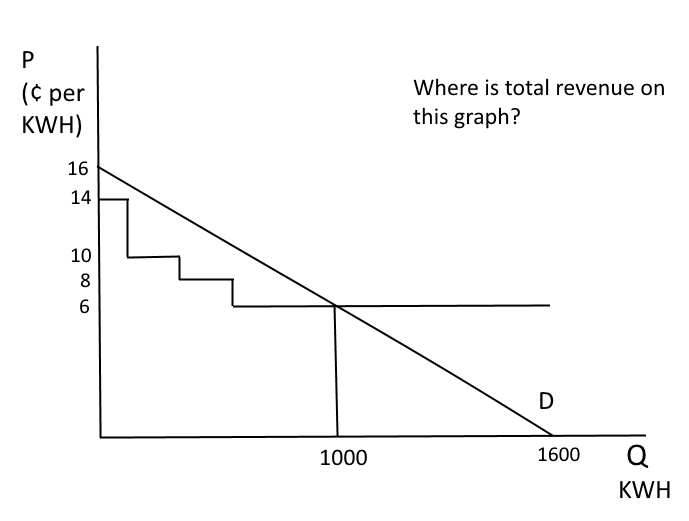

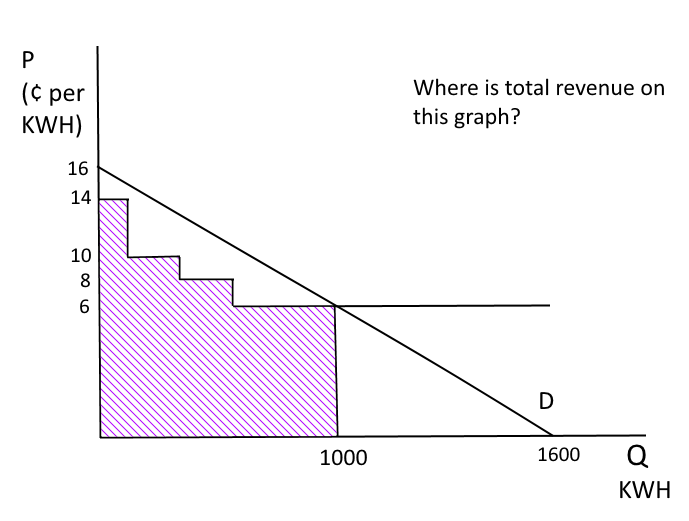

Electrical Power Purchasing

Electrical Power Purchasing

Where is she better off?

Electrical Power Purchasing

Electrical Power Purchasing

Electrical Power Purchasing

So, where is she better off?

Electrical Power Purchasing

-

Quantifies consumer value (what are the units?).

-

Allows us to conduct "normative" analysis (i.e., consumer is "better off" in one situation or another)

-

Based on being "willing and able to pay".

- You might really value things you cannot pay for (food, clothes, health)

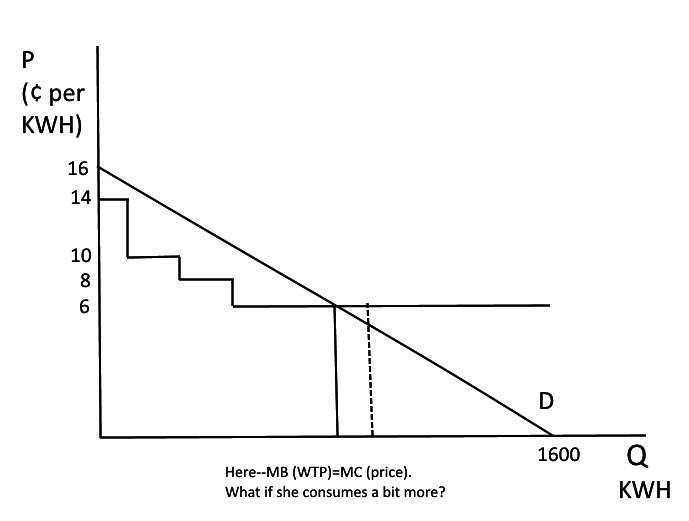

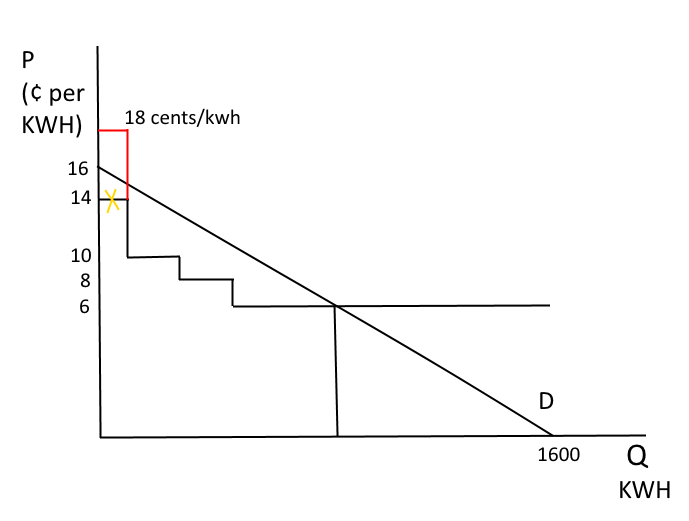

Electrical Power Purchasing

Decision Making on the Margin Rule:

For the consumer, continue to purchase up to point where Marginal Benefit (measured by WTP)=MC

If MB>MC, ↑Q; if MB<MC, ↓Q

This makes the consumer as well off as possible; this decision rule maximizes her consumer surplus

Electrical Power Purchasing

Electrical Power Purchasing

"Thinking on the margin" logic works (most of the time)

Electrical Power Purchasing

Electrical Power Purchasing

Electrical Power Purchasing

In Ann Arbor, Detroit Edison has a somewhat strange rate schedule:

First 500 KWH $.07/KWH

Next 300 KWH $.10/KWH

Remaining KWH $.13/KWH

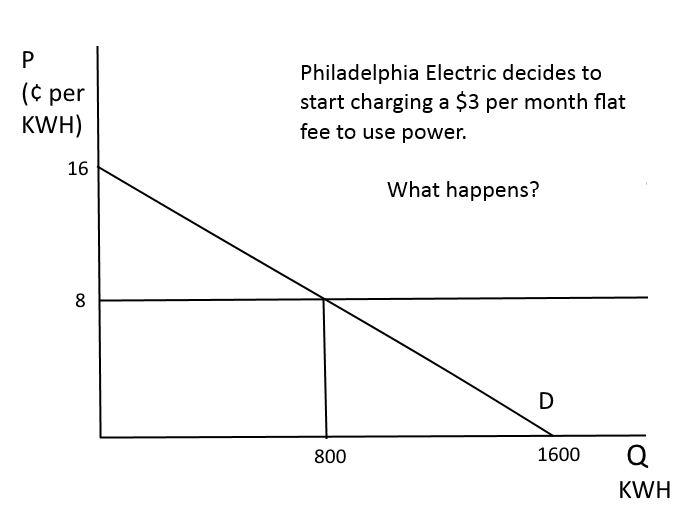

Tiered Pricing

"Water Pricing in Two Thirsty Cities" Since 2001, Santa Fe’s total water consumption has dropped by a fifth, even as the high desert city’s population has increased more than 10 percent. Why?

- Santa Fe, in addition to raising the basic cost of water, decided to make the heaviest users of water pay more — much more …. known as tiered pricing…with water guzzlers paying three to four times more per gallon than more efficient consumers are charged.

- When water costs more as its consumption increases, people respond exactly as an economics textbook would dictate: They use less…per-capita water usage has plunged, falling from nearly 140 gallons a day in 2001 to about 100 now.

- By contrast, in Fresno, which has a single, uniform price for water, per-capita usage was 222 gallons per day last year

-

Tiered pricing offers a balance between fairness and efficiency… Tiered pricing impinges on users who have the most slack…

source: New York Times, May 6 2015

Individual Demand: Two Interpretations

For each price, an individual’s demand curve shows the amount of the good the consumer is willing to purchase (all else equal)

- A positive role: explains how consumers behave

For each quantity, demand represents the consumer’s willingness to pay

- A normative role: demonstrates why and how much consumers benefit from their purchase

Summary

Rational Consumer’s Decision Rule

A consumer “should” buy additional units up to point where marginal value/benefit just equals marginal cost

If WTP > MC, consume/purchase more

If WTP < MC, consume/purchase less

Optimal consumption/purchase Q:

WTP (the marginal benefit of consumption) = MC

Following this rule “maximizes” CS

Summary

“Inframarginal” charges (e.g, fixed fees):

- Do NOT affect the marginal cost of consumption

- May affect a consumer’s decision of whether to purchase a product at all (if CS became negative)

- May affect a consumer’s willingness to pay (and, hence, her demand) for all goods and services she buys by reducing the consumer’s total disposable income (but often these effects are negligible if the fee is small relative to total income)

Does anyone behave this way?

Does anyone behave this way?

Individual consumers:

Maybe not explicitly or consciously, but … pricing incentives DO make a difference

Does anyone behave this way?

Business customers:

Much more likely to make these calculations

explicitly, especially where large amounts of money are at stake (e.g.,

industrial customers (i) who use a lot of electricity and (ii) for whom

self-generation of power is an “economical” alternative).

But, some research suggests consumers are confused

Do Consumers Respond to Marginal or Average Price? Evidence from

Nonlinear Electricity Pricing, American Economic Review, Koichiro Ito

- “…strong evidence that consumers respond to average price rather than marginal or expected marginal price”

- “This sub-optimizing behavior makes nonlinear pricing unsuccessful in achieving its policy goal of energy conservation and critically changes the welfare implications of nonlinear pricing.”

Are average and marginal price different for most products?

The Energy Paradox

What do firms want?

If you were an energy firm, would you want consumers to be highly informed of the marginal cost of your product?

- When would this increase your revenue?

- When would it decrease your revenue?

Course Formalities

email: mille@umich.edu

office: Ross 4416

phone (office): (734) 647-6978

Course web site on Canvas

Course Resources

- Lectures

- Canvas web site: depository for class notes, problem set solutions, practice exams, supplemental readings. Will be used for making announcements so I recommend you adjust your settings to get announcements delivered to your email.

-

Course materials: posted on Study.net

Course Resources

Required (pre-class): cases

Strongly recommended (post-class): practice problems (to check understanding of lectures)

Recommended (pre-class): News articles illustrating class concepts

Textbooks:

(Optional) Textbook: Pindyck and Rubinfeld, Microeconomics, 8th edition, 2012

(Recommended) Study guide for Pindyck and Rubinfeld, by Valerie Suslow and Jonathon Hamilton

Where is the Work?

Very minimal readings – where is the work?

- Active learning:

go over lecture notes in detail, and

do and review all the cases and problems !

- Advice: schedule 5 to 6 hours every week to

go over BE 502 class notes/cases

- do in class problems and problem sets

read case/readings for next class

- Least amount of pre-reading => expect each of you to be well-prepared about case details (Ross Commitment to Learning)

Strategy for Success

Practice, Practice, Practice - You have many problems to work with in this course (Case questions, practice problems in course materials, practice quizzes and exams, Study guide problems), all with solutions – this is critical to really understanding the concepts!!

- If you have difficulty, get help right away (see me, contact the tutor, ask classmates)

- The course is cumulative and moves rapidly. Do not fall behind!

Get Help if you need!

Regular office hours: Tuesday and Thursday, 4:45p - 6:00p

Tutors:

Section 2: Katie Redman (katiered@umich.edu)

Section 5: Abbey McDonald (abbeymc@umich.edu)

Evaluation

Two take-home, open-book quizzes (15% total):

Quiz 1 (5%): due Monday, Sept 19, 9:00AM

Quiz 2 (10%): due Monday, Oct 3, 9:00AM

3 group assignments (25% total):

Assignment 1 (5%): due Monday, Sept 12, 9:00AM

Assignment 2 (10%): due Monday, Sept 26, 9:00AM

Assignment 3 (10%): due Monday, Oct 10, 9:00AM

Quizzes and group assignments are turned in on Canvas.

Evaluation

Participation (10%):

- Attendance + punctuality will be 5%; Quality of participation important for rest 5%

- Please report all absences using iMpact Class Absence Reporting tool

Final Exam (50%): Thursday, October 20, 4:45pm-7:15pm

Evaluation

Conditions that make performance improve rapidly often poor for long-term retention, whereas conditions that appear to create difficulties, slowing the rate of apparent learning, often optimize long-term retention.

E.g. Tests as learning events (Roediger and Karpicke 2006):

Three conditions:

- SSSS: four consecutive 5-min study periods

- SSST: three study period plus a test of recall for the passage

- STTT: one study period plus three consecutive tests of recall for the passage

STTT resulted in higher proportion of long-term retention

The weekly tests/assignments intended to improve long-term recall

Grading

Final grades in core courses at the RSB are on a forced curve:

- First 25% get Excellent

- Next 35% get Good

- Next 35% get Pass

- Next 5% get Low Pass

Fail grade if exams reflect a lack of understanding of key basic concepts

Classroom Protocol

Please sit per seating chart

Namecards – please use them throughout!

Handouts – distributed in class and via Canvas

Missed classes – please:

- report in online system and inform me via email

- get notes from Canvas or from classmates

Avoid:

- late arrivals / comings and goings / ringing cell phones / open laptops

Course Material

Generally same materials across all sections

The course is about how microeconomics helps us understand and predict:

Private decision making by

- consumers & firms

- employees, competitors, suppliers, etc

Public policy (government) decisions and their effect on your firms

A way of thinking about the (business) world!

Course Outline

FOUNDATIONS (1st half of course)

- Module 1: Individual and then market demand

- Module 2: Costs - & how they underlie supply

- Module 3: Profit maximization with Market Power

- Module 4: Perfectly competitive markets

- Module 5: Supply and demand analysis

Course Outline

ADVANCED TOPICS (2nd half of course)

- Module 6: Decisions with risk and asymmetric information

-

Module 7: Advanced pricing strategies

- Module 8: Oligopoly, game theory, and how firms interact in markets

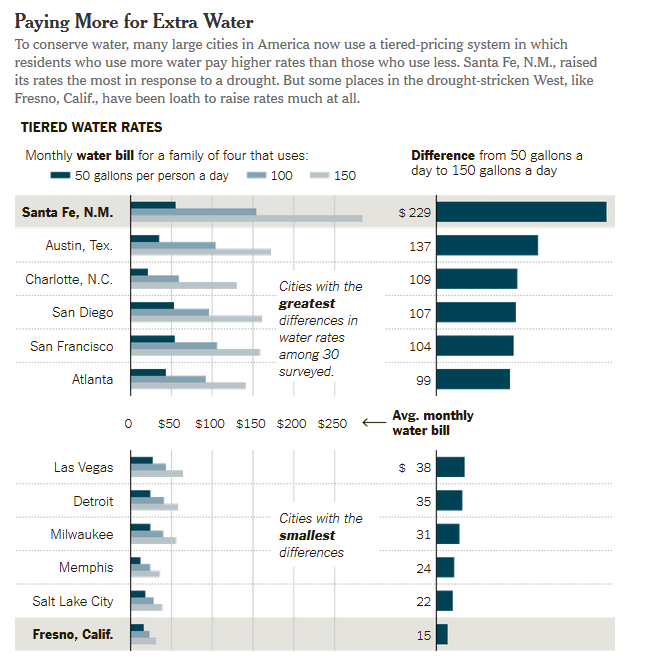

Course Outline

Economics: more "conceptual" than other courses, but strongly connected

Thinking Like an Economist

Some key elements:

- Comparing costs and benefits

- Using marginal analysis i.e. look at the cost/benefits from each additional unit

- Recognizing opportunity and sunk costs

Immediately coming up!

- A practice quiz (PracticeMC_Quiz1.pdf) is posted on Canvas along with answers. These questions will help you evaluate your understanding and are relevant for the first group assignment.

-

Your team for the group assignments is posted on Canvas.

-

Tutor(s) will be available from Wednesday afternoon on--email them for appointments.

- Read case Tagamet on demand estimation, try to answer questions, be ready for discussion.

Lecture 1

By umich

Lecture 1

- 3,864