Applied

Microeconomics

Lecture 13

BE 300

Plan for Today

Risk/uncertainty

Risk preferences

Insurance

Behavioral economics of risk

Next Time

- Read through "Failures in Franchising" (not to turn in).

- Readings listed last time will be continued ("Behavioral Economics of Risk" article; Ch 14.1-14.4; Ch 4.6)

Additional info

Tutoring this week is Wed., Feb. 25 in R0216 and 5:30 - 7:30.

No review session this week.

Interested in interning abroad in a developing country? Humanitarian Technology Design Internships (issues related to transportation infrastructure and water supply) -- I have posted info on the CTools site for those interested.

Risk

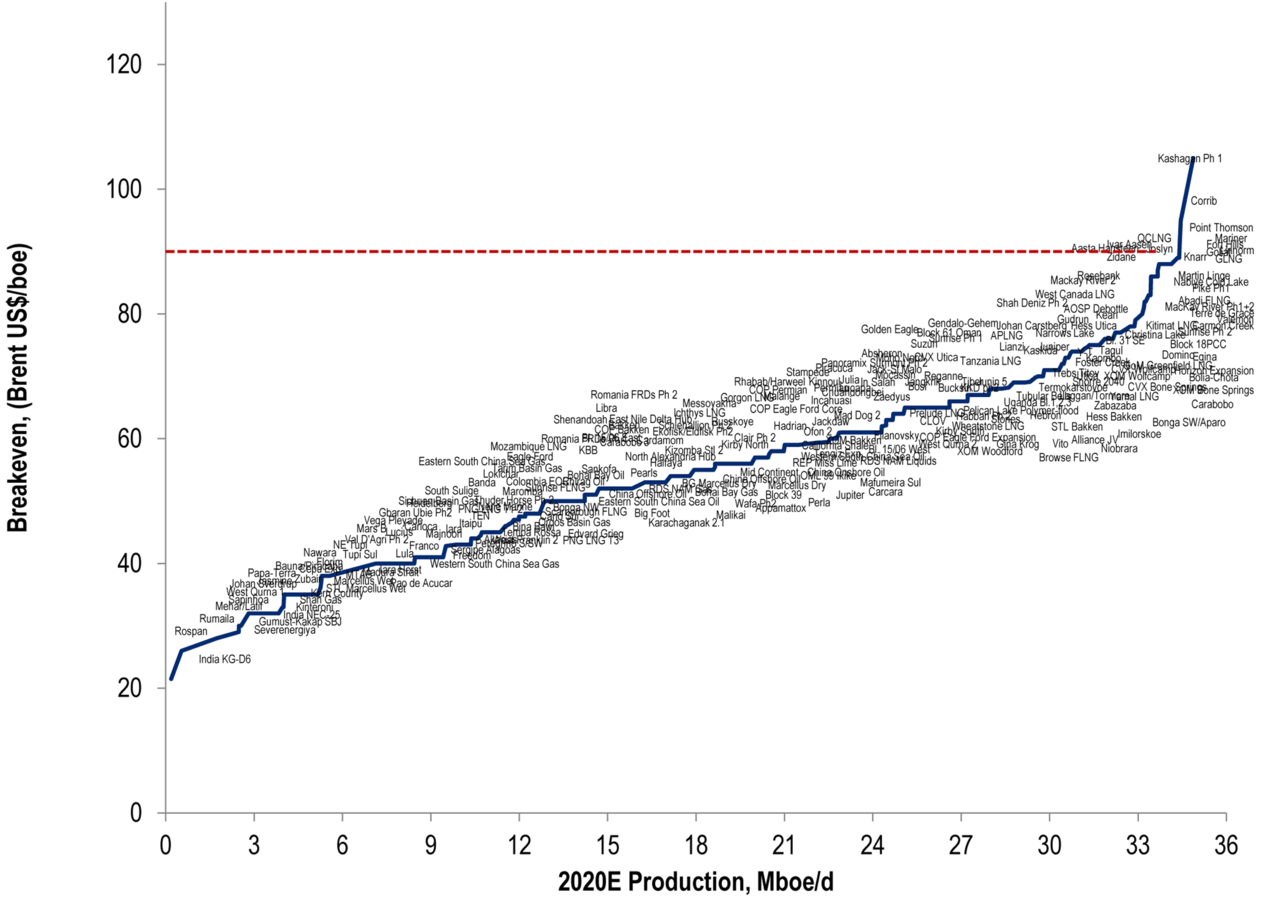

In calculating profits for the case last time, we used expected value. Recall:

where "Wi" is the payment you receive if event i occurs, and "pi" is the probability that event occurs.

Risk

Hat tip Jacob Marples for the figure.

In the oil case (last class): a manager had to decide whether or not to drill a well, given that the price of oil will change. How did the manager make the decision using expected value?

Risk

Gregg, a promoter, is considering whether to schedule an outdoor concert on July 4th. Booking the concert is a gamble: He stands to make a tidy profit if the weather is good, but he’ll lose a substantial amount if it rains.

Risk

Probability: number between 0 and 1 that indicates the likelihood that a particular outcome will occur.

- If an outcome cannot occur, probability = 0. If the outcome is sure to happen, probability = 1. If it rains one time in four on July 4th, probability = ¼ or 25%.

- Outcomes are mutually exclusive (either it rains or it doesn’t) and exhaustive (no other outcome is possible). So probabilities must add up to 100%.

Gregg, a promoter, is considering booking a concert on July 4th. It may or may not rain.

Risk

Calculating Probabilities using Data or “Best Guess”

- Gregg has data about raining on July 4th : number of years that it rained (n) and the total number of years (N). Frequency: Ө = n/N

- If Gregg wants to refine the observed frequency, he can use a weather forecaster’s experience to form a subjective probability: best estimate of the likelihood that the outcome will occur—that is, our best, informed guess.

Gregg, a promoter, is considering booking a concert on July 4th. It may or may not rain.

Risk

Gregg thinks the probability of rain is 50%. He makes 15 thousand if it does not rain and loses 5 thousand if it does rain.

Greg can book the venue well in advance and pay only $1,000 for space and equipment.

Or, he can book the venue last minute and pay $10,000 for space and equipment, but he will know from the weather report if it will rain and can choose not to book. For simplicity, in this problem assume he has a 0% discount rate (i.e., no need to calculate present value).

a) What is the expected value of booking today?

b) What is the expected value of waiting until the last minute to make a decision?

c) Based on expected value, should he wait, or should he book today?

Gregg, a promoter, is considering booking a concert on July 4th. It may or may not rain.

Risk

So far we have just been comparing expected values.

But maybe expected value is not the only thing we care about...

Risk

Consider this gamble.

Gamble 1:

50% probability of winning $101

50% probability of winning $99.

What is the expected value of playing this gamble?

Risk

Expected value: 0.50 x $101 + 0.50 x $99 = $100

Would you be willing to pay $99.50 to play this gamble?

Risk

Now take a second gamble

Gamble 2:

1% probability of winning $10,000

99% probability of winning $0.

What is the expected value of playing this gamble?

Risk

EV = 0.01*10000 + 0.99*0 = $100

Are you still willing to pay $99.50 to play?

Risk

Now consider a third gamble:

Gamble 3:

1% probability of winning $1,000,000

98% probability of winning $0

1% probability of losing $990,000

Are you still willing to pay $99.50 for this gamble?

Risk

All three gambles have the same expected value.

Gamble 1: 50% chance $101, 50% chance $99.

Gamble 2: 1% chance $10,000, 99% chance $0.

Gamble 3: 1% chance $1 mill, 98% chance $0, 1% chance -$990,000

Why is our willingness to pay different for these three gambles, if the expected value is the same?

Risk

All of the preceding examples have the same expected value. But they differ in the “spread” of the possible outcomes.

Risk

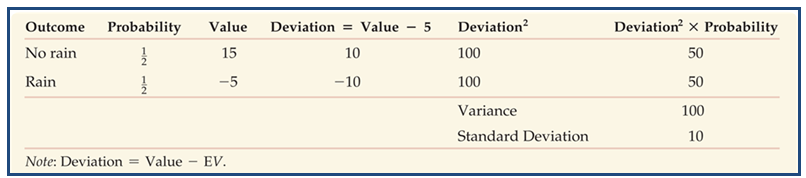

A common measure of the spread of outcomes is the variance.

"On average," how much does each outcome differ from the expected value (squared)?

On average, how large is the squared deviation from the expected value?

If each outcome (Wi) is close to the expected value (EV), the variance is small. If they are far away, the variance is larger.

Risk

Back to Gregg, the promoter...

Note: We call the square root of the variance the "standard deviation"

Risk

If people made their choices to maximize expected value, they would always choose the option with the highest expected value regardless of the risks involved. They go with the option that, "on average," gives the highest payoff.

This is how we assumed the manager of the oil reserve and Gregg, the concert promoter, would behave.

This how risk neutral individuals behave

Risk

Most (all?) of us care about more than just expected value.

Even if two courses of action have the same expected value, we would prefer the "sure thing" over the risky outcome.

This how risk averse individuals behave.

Risk

Risk neutral: indifferent between a sure outcome and an uncertain outcome with the same expected value

Risk averse: preference for a sure outcome over an uncertain outcome with the same expected value

To avoid risk, a risk averse person will be willing to pay a risk premium.

Alternatively, such a person will require extra compensation to get them to accept a risk

Risk loving: preference for an uncertain outcome over a sure outcome with the same expected value

Risk

Risk neutral, Risk averse, Risk loving are three categories that describe individuals' risk preferences -- that is, how individuals feel about bearing risk.

Risk

If Ann is willing to pay up to $450 for insurance against a loss of $7000 which will occur with a 5% probability, she is:

(a) Risk-neutral

(b) Risk-averse

(c) Risk-loving

Risk

If Ann is willing to pay up to $450 for insurance against a loss of $7000 which will occur with a 5% probability, the expected value of the insurance contract is $7000 x 0.05=$350.

Ann would rather lose $450 for sure than pay $7000 with a 5% probability and 0 with a 95% probability, even though the expected value of the loss is lower than $450.

Therefore she is risk averse.

Risk

If Ann is willing to pay more than the expected value in order to reduce risk, that means she is risk-averse.

If we know Ann is risk averse, we know she is willing to pay more than the expected value.

But--we don't know how much more she is willing to pay. It depends on how much she doesn't like risk.

Risk

Many public utilities offer interruptible service to industrial customers who pay less for their electricity but are subject to interruptions in service during peak periods. Suppose there is a 25% chance of a firm's power being shut once in a week (and then 75% chance of no shut down) under interruptible service. Suppose also that each interruption costs $1200 to the firm in lost profits. Then, in order to get continuous service :

- a risk neutral firm would surely pay an extra $400 per week

- a risk loving firm would surely pay an extra $300 per week

- a risk averse firm would surely pay an extra $300 per week

- a risk averse firm would surely pay an extra $400 per week

Risk

Risk averse people choose actions or situations with higher risk only if the expected value is higher than that of a less risky alternative--hence the market relationship between risk and return in Finance.

Risk-neutral players maximize expected values.

Risk-averse people (i.e. most of us most of the time!) maximize their expected “utility” or “well-being” - not expected value.

Risk

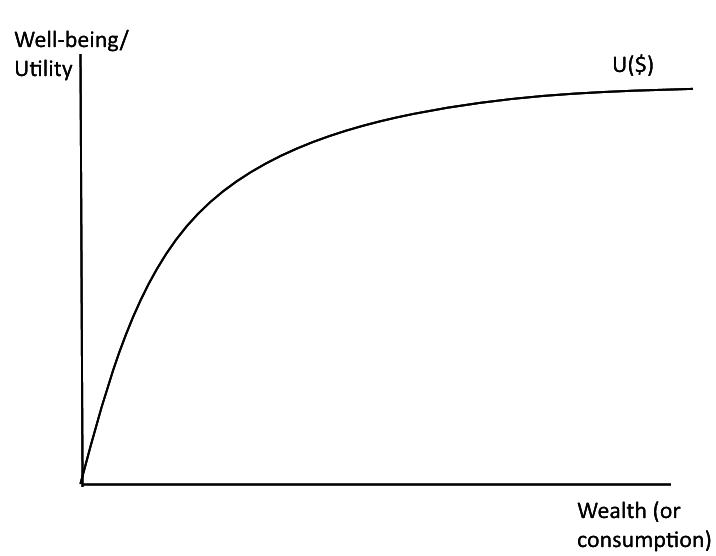

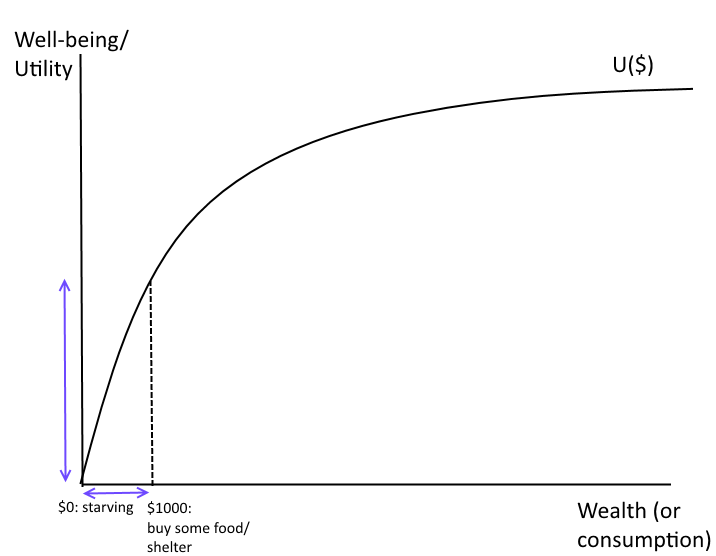

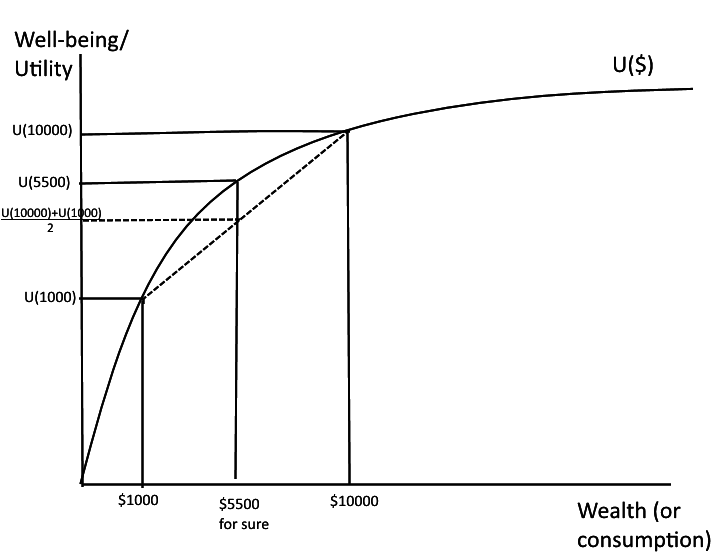

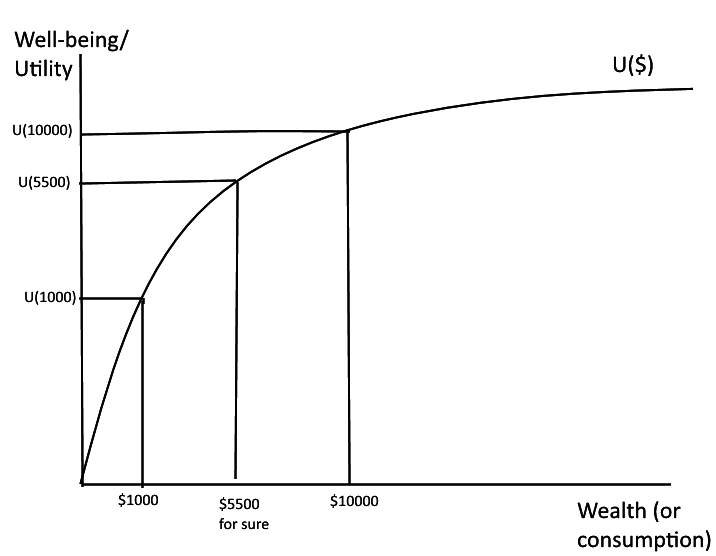

Risk aversion implies that there is diminishing marginal utility of wealth/$/consumption. Imagine the relationship between happiness or well-being (economists call "utility") and wealth can be graphed.

Risk

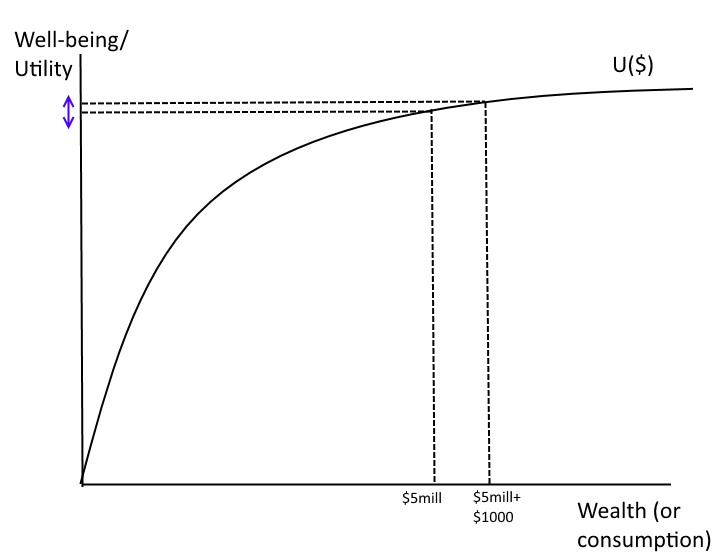

Risk aversion implies that there is diminishing marginal utility of wealth. Imagine the relationship between happiness or well-being (economists call "utility") and wealth can be graphed.

Risk

Risk aversion implies that there is diminishing marginal utility of wealth. Imagine the relationship between happiness or well-being (economists call "utility") and wealth can be graphed.

Risk

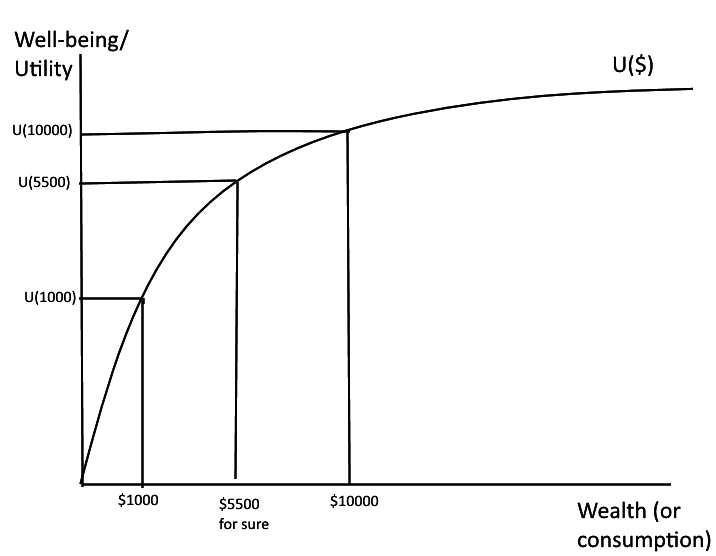

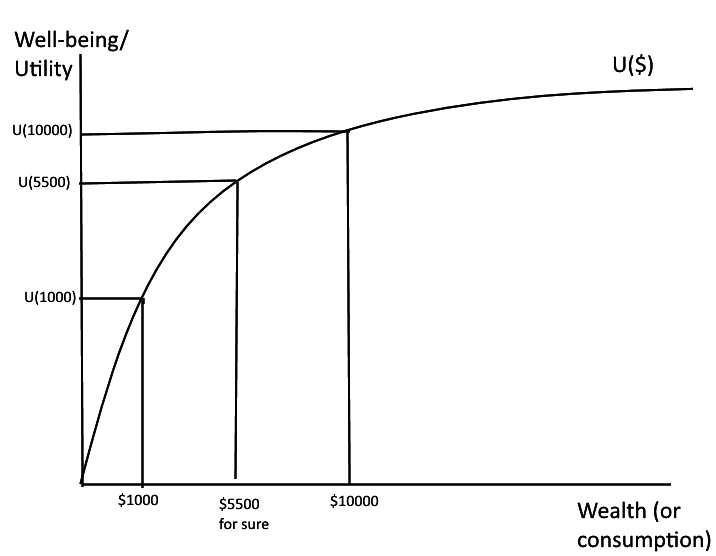

Imagine this is your utility function and you consider a bet that gives you $10000 with probability 0.50 and $1000 with probability 0.50. What is your expected winnings? How would you find your expected utility?

Risk

Expected payoff is $5500. But expected utility is 0.50 x U(10000)+0.50xU(1000) -- which is lower than U(5500). Put differently, you would have higher expected utility if you got $5500 for sure than if you got $10000 with probability 0.50 and $1000 with probability 0.50.

Risk

Even if the expected value of the bet is $5500, the expected utility of the bet is less than the utility of getting $5500 for sure. If you want to maximize utility you should want less risk!

Risk

Put differently: if you are risk averse, it hurts more to lose money than it feels good to win money.

RiskMitigation

How do we deal with risk?

Risk Mitigation: take actions to reduce your risk exposure

- Diversification

Risk Financing: Pay money to transfer the risk to a third party. Changes a possible high cost to a certain lower cost.

RiskMitigation

As long as two investments or economic activities are not perfectly positively correlated, the variance of a combination of them will be lower than the variance of the investments themselves (for the same total investment).

- lower risk for same return!

The less correlated the returns, the greater risk protection you receive

RiskTransfer

Risk mitigation (diversification, acquiring information, taking actions to lower your risk) actually reduces the riskiness of an asset or portfolio.

Risk transfer does not reduce the risk, but it transfers it to a third party (like an insurer)

Risk is like garbage--you pay someone to take it away

RiskTransfer

With insurance, consumers can transfer risk to an entity (the insurance company) that can better bear it.

Note: this strategy is costly, so it should be used only for non-diversifiable risk

Actuarially fair insurance is insurance whose price is equal to the expected loss.

If cost of loss is 100,000 & probability of loss is .05

Expected loss = 100,000*.05 = $5000

Actuarially fair insurance would cost $5000

Who, among the risk neutral, risk loving, and risk averse, will always buy actuarially fair insurance

RiskTransfer

Suppose you own a house that is worth $300,000. The probability of a fire at your house is estimated to be about 0.01.

(a) What is your expected loss from fire?

(b) If you are risk neutral, what is the maximum amount you would be willing to pay for fire insurance?

(c) What can we say about what you would pay if you were risk averse?

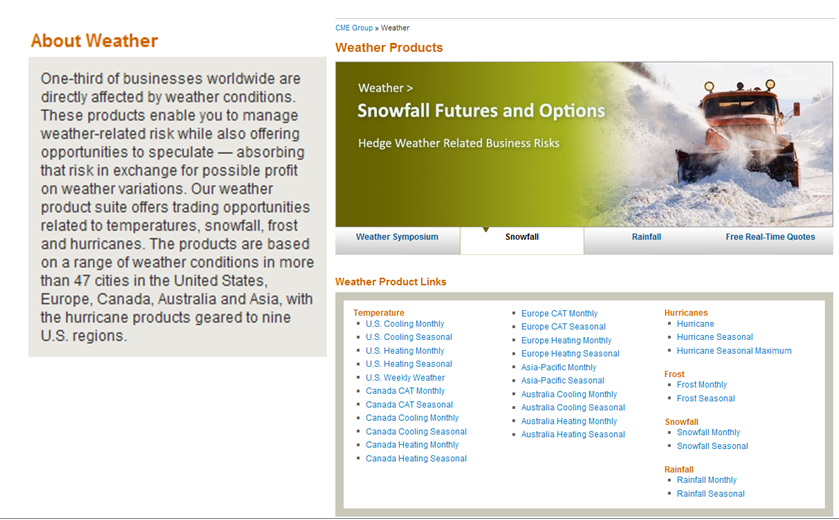

Futures Markets

One way to transfer risk is through futures markets.

In a spot market: exchange of $ for product occurs immediately.

In a futures market: promise (contract) to buy or sell a particular commodity at a specified time or place at a pre-specified price.

Futures Markets

For futures markets to function, a commodity must be widely traded and interchangeable.

- Futures transactions take place on an organized exchange (such as the Chicago Board of Trade, New York Mercantile Exchange (both owned by CME Group)).

- In futures contracts, the identity of the party you are transacting with is not important; futures contracts are standardized and tradable.

Futures Markets

Futures Markets

Example: Currency Risk

Suppose:

- a risk averse U.S. medical equipment manufacturer expects to have devices ready ship to France this June for a fixed price of €100/unit, but needs to pay his own bills in $USD.

- The current $/ € exchange rate for a June futures contract is $1.10 dollars per euro – this means you deliver USD at $1.10 per Euro €1 in June.

- there is a 50% probability of appreciation of the euro to $1.25 and a 50% probability that it will fall to $1.00.

What is the manufacturer worried about happening -- euro appreciation or euro depreciation?

Futures Markets

Example: Currency Risk

Because the manufacturer is risk averse, she would like to lock in the $1.10 exchange-rate and her USD price of $110 per unit.

To do so, the manufacturer would want to go "short" in the futures market, that is, to contract to sell Euros at $1.10 in June. This is called a short hedge.

She is selling a commodity (euros) that she doesn't currently have, but will promise to deliver in the future at a specified price.

Futures Markets

How this works:

The futures contract

- Specifies the ex-rate for USD/Euro

- Specifies the quantity

- Specifies the quality – this can be harder to verify, hence the reason futures contracts typically exist only for commodities and homogeneous goods like currencies

Futures Markets

How this works:

•Manufacturer is short on Euros – has promised to sell in future at $1.10/euro.

•Buyer of the futures contract is long – has promised to buy in the future at $1.10/euro.

•Everyday, the account of manufacturer is debited or credited by the change in the price of the futures contract on the market.

Futures Markets

What happens at the close of the contract?

- Buyer and seller accounts on futures market are settled in cash

- Manufacturer sells his devices and receives cash IN EUROS that can be exchanged for dollars at prevailing ex-rate.

- His profit or loss on the futures contract adds or subtracts from proceeds from the medical device sale

- Buyer of the ex-rate futures contract can use excess profit on contract to buy euros at market ex-rate, which is $1.10 net of profit/loss on futures contract.

Futures Markets

What actually happens?

Case I: The dollar weakens (Euro strengthens) to $1.25 per Euro.

Manufacturer gets:

French transaction (€100*1.25): $125.00

Futures transaction:

Must sell euros at $1.10; net loss: -$15.00

Net revenue per unit: $110.00

Futures Markets

What actually happens?

Case II: The dollar strengthens (Euro weakens) to $1.00 per Euro.

Manufacturer gets:

French transaction (€100*1.00): $100.00

Futures transaction: Sells euros at $1.10, buys euros at $1.00; net gain: $10.00

Net revenue per unit: $110.00

Futures Markets

Instead of a gamble with $100 and $125 outcomes, the manufacturer will always get $110. Is there another way to get this outcome?

Does Expected Value Drive Choice?

Dealing with risk is one area where economic models of behavior often don't match reality.

Example from Tversky & Kahneman (1981) proposing government policies to address an unusual disease (avian flu) which is expected to kill 600 people/year

•If Program A is adopted, 200 people will be saved

•If Program B is adopted, there is a 1/3 probability that 600 people will be saved & a 2/3 probability that no one will be saved

Which would you select, based on this information (where the probabilities are the result of reliable scientific research on the disease)?

Does Expected Value Drive Choice?

Now consider an alternative choice of programs aimed at combating the disease (avian flu) which is expected to kill 600 people/year:

- If Program C is adopted, 400 people will die

- If Program D is adopted, there is a 1/3 probability that no one will die & a 2/3 probability that 600 will die

Which would you select, based on this information?

- Even though program C is identical to program A, most people (78%) in the experiment chose Program D (riskier, but possibility of no losses)

- Attitudes toward risk are reversed for gains vs. losses: risk averse for choices involving gains; often risk preferring when making choices about losses

Behavioral Economics

Actual behavior & decision making are frequently inconsistent with utility theory/expected value analysis

Perceived value, which drives rational decisionmaking, depends on circumstances.

Sometimes we do make rational, unbiased choices:

- Experience & expertise => good intuitive choices

- Situations requiring “slow thought” tend to be less biased

What type of choice biases do we observe?

Exercise Solutions

Gregg, concert promoter...

a) Expected value of concert today: 0.50 x 15000+0.50x(-5000)=$5000. Can book concert venue today for $1000. So expected profit would be $5000-$1000=$4000.

b) Expected value of waiting: 50% chance it rains and Gregg does not book the venue, makes $0. 50% chance it does not rain and Gregg books the venue, makes $15,000 but must pay $10,000 for space and equipment. So expected value of waiting is 0.50 x 0 + 0.50 x (15000-10000) = $2500.

c) Because $4000 > $2500, based on expected value it is better for Gregg to book today to lock in the lower cost.

Lecture 13

By umich

Lecture 13

- 487