Applied

Microeconomics

Lecture 14

BE 300

Plan for Today

Risk in Markets/Failures in Franchising Case

Behavioral economics of risk

Start economics of information

Next Time

"Zombie Apps" case

"Get Paying Users by Giving Your App Away" Article

Ch. 15 intro, Ch. 15.1–15.2

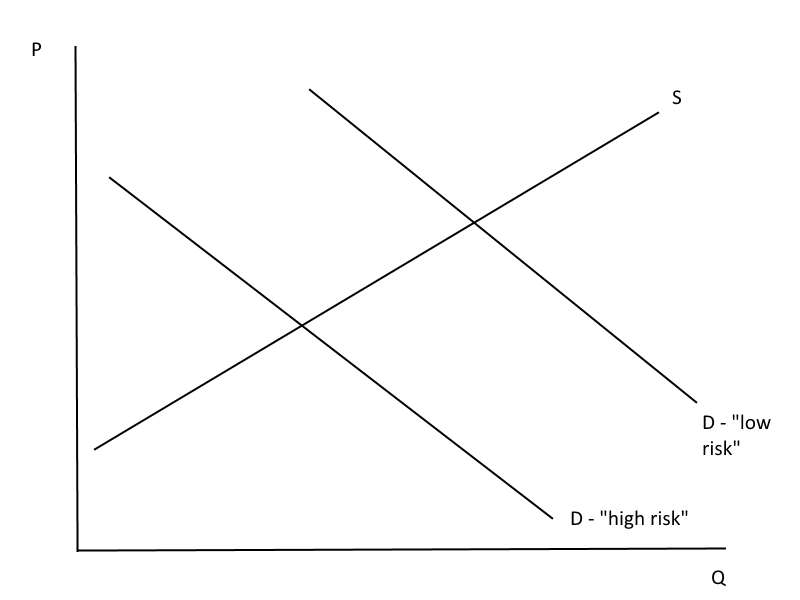

Risk in a Supply/Demand Framework

Different market arrangements result in different sharing of risk:

- Who bears the currency risk in an international exchange?

- Do courts hold medical device manufacturers liable for product malfunctions, or does that liability fall on consumers?

- How do different types of contracts split risk between different parties?

The way risk is shared can affect the price and quantity in a supply and demand framework.

Failures in Franchising

In the case you read for today, we look at how risk is shared in franchise agreements.

A franchise is typically defined as a contractual agreement between two legally independent firms whereby the franchisor grants the right to the franchisee to sell the franchisor's product or do business under its trademarks in a given location for a specified period of time. In return, the franchisee agrees to pay the franchisor a combination of fees, usually including an upfront franchise fee and royalties calculated as a percentage of its outlet's sales. Most analysts agree that about 35 to 40% of retail sales in the U.S., or about 15% of GDP, go through franchised businesses.

Failures in Franchising

Assume

- when a new retail/service business goes bankrupt any time in the first five years, the owners incur losses of about $500,000. That if the business makes it through the first five years, it is viable and the owners do not incur any losses at all.

- Assume that the losses incurred upon failure and the profitability of the business are the same whether the business is franchised or independent.

(just to keep things simple)

Failures in Franchising

Suppose that the risk of a franchise failing in its first five years was (perceived to be) 10 percentage points lower than that of an independent business (so e.g. it might be 20% instead of 30% for independents). Everything else constant, how much more should a risk neutral potential franchisee be willing to pay for a franchise compared to an independent business start-up?

Remember--losses if the business fails are $500,000

Can you say anything about what this amount would be for a potential franchisee if she were risk averse?

Failures in Franchising

Think of the "demand" for franchises from entrepreneurs considering opening a business. How would the perception that franchises are relatively low risk affect demand?

Failures in Franchising

How does being perceived as "low risk" affect the price that the franchise association can charge for the franchise?

Failures in Franchising

How does the degree of risk aversion among franchisees affect this analysis?

Failures in Franchising

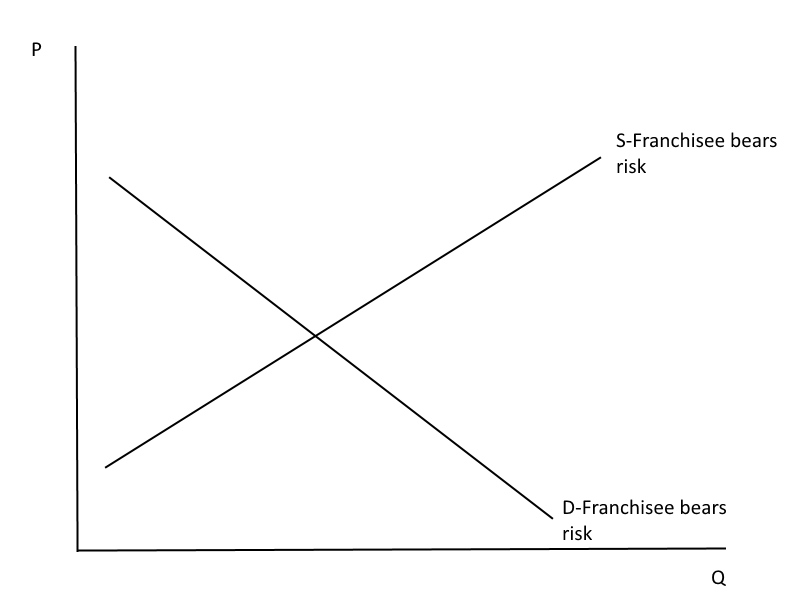

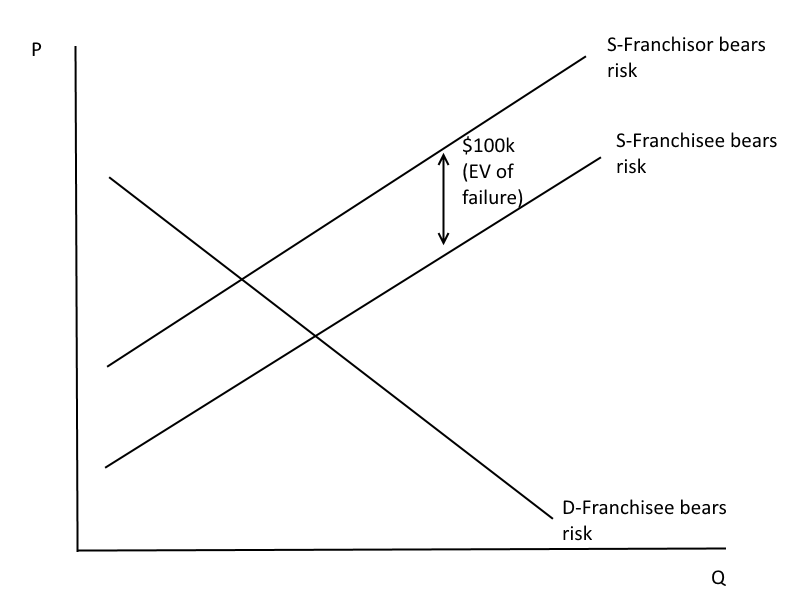

There have been regular discussions in various states about enacting franchisee protection legislation. Suppose that a new law required franchisors to compensate franchisees fully for their losses if failure occurred (in other words, give them $500,000 upon failure to compensate all their losses). Everything else constant, how would enacting such a law affect the price at which franchises are sold relative to the current regime where franchisees bear the risk of failure?

Assume that franchisors are risk neutral and franchisees are risk averse, and that the risk of failure is some fixed number, e.g. 20%.

Failures in Franchising

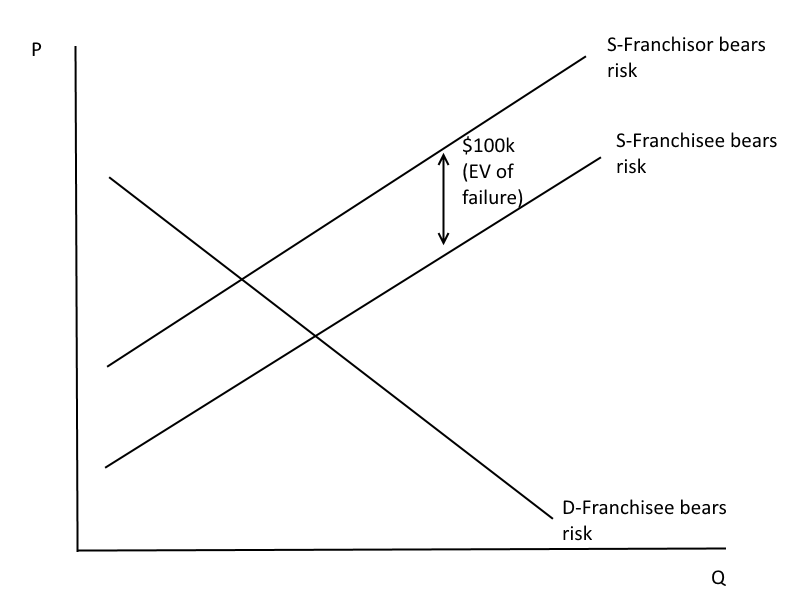

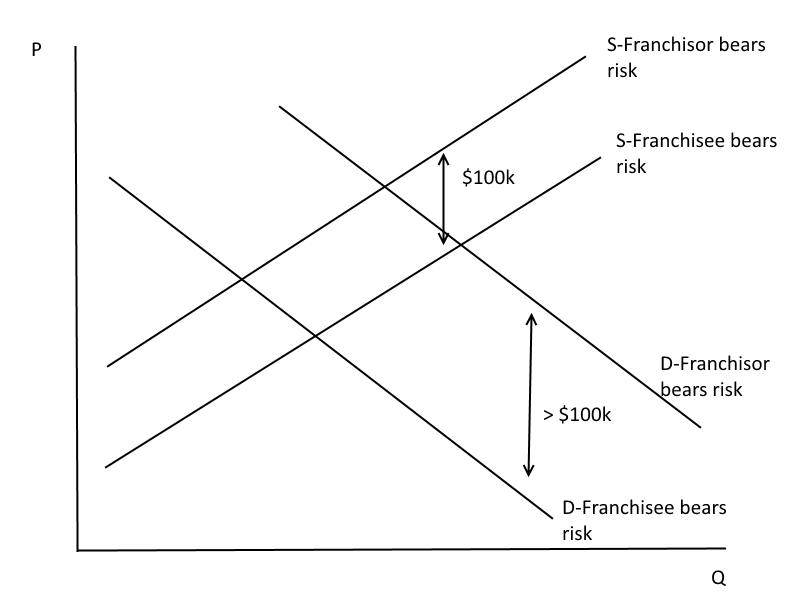

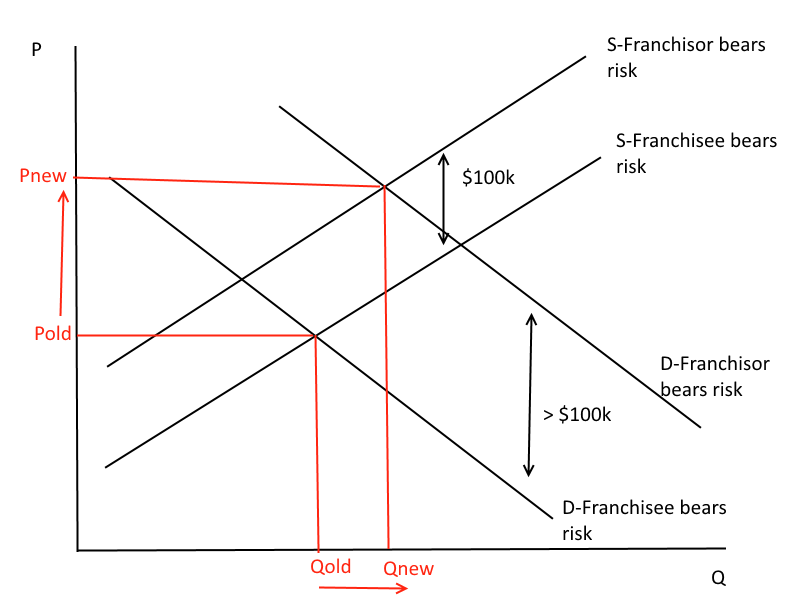

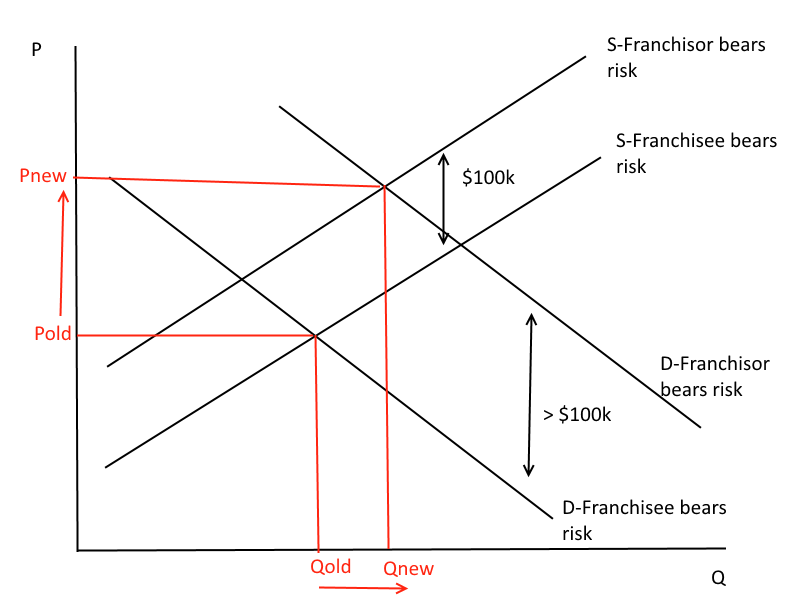

If the franchisors (supply) is risk neutral, how will shifting the risk of failure to the suppliers shift the supply curve?

Failures in Franchising

If suppliers are risk neutral--for each franchise they supply they must be compensated only for the expected value of the risk ($100k)

Failures in Franchising

How would shifting risk from the demanders (franchisees) to the suppliers (franchisors) affect the demand for franchises?

Failures in Franchising

So, would this increase or decrease the Q of franchises? What about the price?

Failures in Franchising

Is it more efficient (higher total surplus) to have the franchisor or the franchisee bear the risk?

Failures in Franchising

So, are there any reasons to keep the risk on the franchisee, even though they are risk averse?

Failures in Franchising

This case illustrates how the risk preferences of suppliers or demanders affect the market outcome--if you know the risk preferences, you should be able to make some predictions about how shifting risk will affect price and quantity.

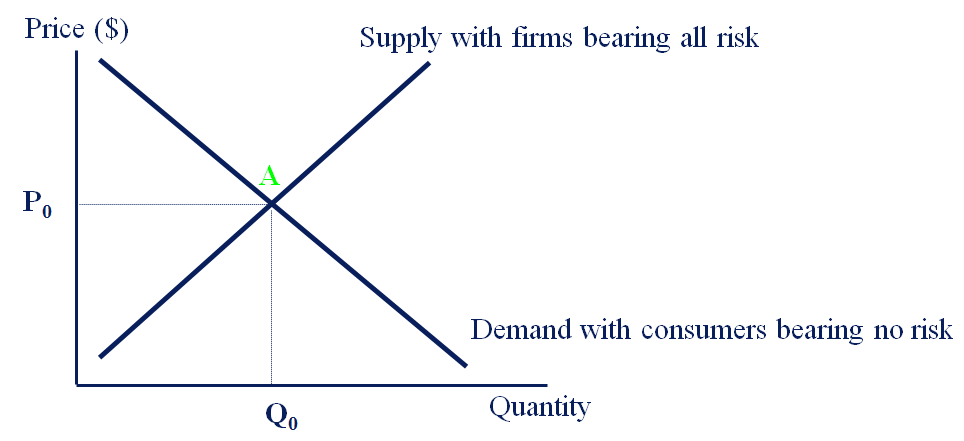

Risk in a Supply/Demand Framework

Another example:

The “security lighting” industry sells outdoor lights with motion sensors. These bright lights immediately turn on if motion is detected. The probability that a light will fail is 10%. Assume that if it fails, there is a 1% chance that the house will be robbed and that the owner will lose an average of $25,000 in cash and personal belongings.

Risk in a Supply/Demand Framework

- Currently, the courts have been ruling against the industry and awarding the homeowner damages equal to their expected loss. Recently, the courts announced that they will move to a system where the liability will be split evenly between the firm and the consumer (so that each has to bear half of the expected loss).

- Assume that lighting firms are risk neutral, homeowners are risk averse, and the market for these lights is competitive.

How can we use demand and supply analysis to predict what will happen to the price and quantity of security lights sold? How does this answer change if both parties are risk neutral?

Behavioral Economics: Perceived Value

Actual behavior & decision making are frequently inconsistent with utility theory/expected value analysis

Perceived value, which drives rational decision-making, depends on circumstances.

Sometimes we do make rational, unbiased choices:

- Experience & expertise => good intuitive choices

- Situations requiring “slow thought” tend to be less biased

Behavioral Economics

Biases in decision making

- Framing (context) influences choices

- Loss aversion bias

- Anchoring bias

- Confirmation bias

- Overconfidence bias

- Status quo bias

- Endowment effect

- Default effect

Miscalculation of probabilities

- Law of small numbers bias

- Gambler’s fallacy

- Certainty effect

- Low-probability gambles

Behavioral Economics

Loss Aversion: prefer avoiding losses to obtaining gains

- resistance to selling a stock that has lost value b/c you’ll have to take a loss; the purchase price was your “reference point”

- resistance to divesting a poorly performing division of a company or cancelling a project and recognizing the losses

Can drive the "sunk cost" fallacy!

Behavioral Economics

Anchoring: people tend to rely heavily on the first piece of information they receive. Decisions are made by comparing the outcomes to the "anchor."

E.g., Participants asked if Mahatma Gandhi died before or after age 9. Then, they were asked to estimate his age at death.

A separate group were asked if Mahatma Gandhi died before or after age 140, then was asked to estimate his age.

The first group estimated much lower ages than the second group, even though obviously both age 9 and age 140 were wrong.

Behavioral Economics

•Confirmation bias: tend to gather information that confirms your prior beliefs and discount or ignore information that contradicts prior beliefs (see McKinsey article on Ctools for some good discussion of this)

•Overconfidence bias: tend to place too much confidence in the accuracy of your analysis (see Kahneman, NY Times Magazine article, 10/19/2011)

Behavioral Economics

Experiment: cup allocation

Status Quo bias:

- Endowment effect: value something you own more than one you do not (i.e., gap between what you are willing to pay for a good & what you are willing to sell a good for)

- Default effect: when confronted with many alternatives, people avoid making a choice and end up with the default option (the one assigned)

Behavioral Economics

People systematically miscalculate probabilities:

•Law of small numbers bias: overstate probability that certain events will occur (based on little information), e.g., shark attacks, airplane accidents, etc.

•Overestimate likelihood of infrequent events

•Underestimate likelihood of more common events

Gambler’s Fallacy: False belief that past events affect current, independent outcomes (“on a roll”)

Behavioral Economics

Lottery Example:

Powerball is a multistate lottery game offered in 43 states, Washington D.C., and the U.S. Virgin Islands. One panel equals one play. One play cost $2.00.

- Odds of winning jackpot (currently $60M): 1 in 175,223,510

- Odds of winning $7: 1 in 707

- Overall odds of winning: 1 in 32

Keno: One panel equals one play. One play cost $1.00.

- Odds of winning $250,000: 1 in 2,546,203

- Odds of winning free $1 ticket: 1 in 32

- Overall odds of winning: 1 in 19

Behavioral Economics

When making complex decisions, people often rely on rules of thumb (“heuristics”)

- A good rule of thumb is derived through trial and error or by imitating others who have made successful decisions

- A good rule of thumb can economize on decision making costs (and can be nearly optimal)

However, behavioral economists & psychologists find that there are also rules of thumb that can be inherently biased (and not generate the “rational” result)

Summary: What Do Behavioral Studies Show?

•Probabilities are rarely known; usually probabilities are subjective or unknown

•Overconfidence and confirmation bias are related to our inability to accurately gauge probabilities

•The status quo matters: changes are relative to your starting point; and reference points (e.g., anchoring) affect choices

•Framing matters: a choice between two “gains” vs. a choice between two “losses” may result in a different decision;

•Attitudes toward risk are reversed for gains vs. losses (reflection effect):

~People are risk averse for choices involving gains

~People are risk loving for choices involving losses

Further Reading

•http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/23/magazine/dont-blink-the-hazards-of-confidence.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 (example of overconfidence bias – great story)

•http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/09/business/learning-to-mistrust-your-financial-instincts.html?pagewanted=print (examples of biases applied to financial decisions)

•http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/27/books/review/thinking-fast-and-slow-by-daniel-kahneman-book-review.html?pagewanted=all (review of book)

Exercise Solutions

The market starts out like this:

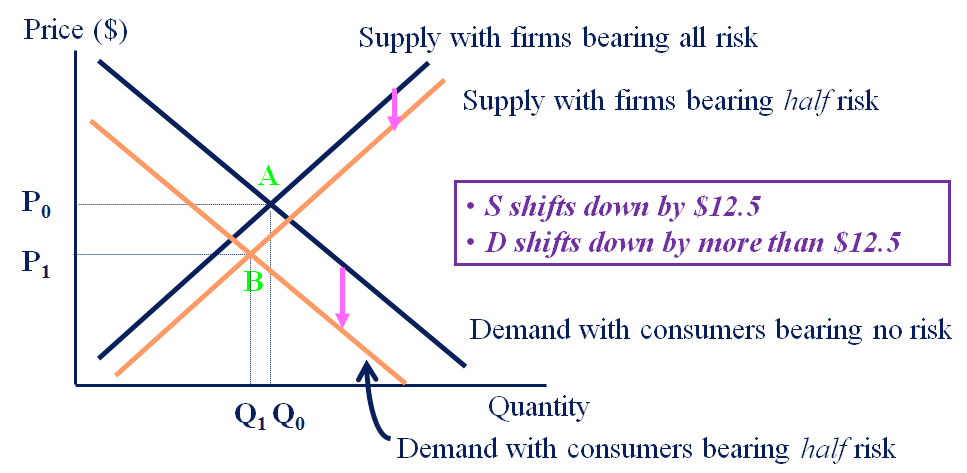

Exercise Solutions

Start at A where firms bear all the risk.

- E(loss) = 0.01[(0.10)(25,000)] = $25. Therefore, if they each share half of the liability, the expected monetary loss for each party is $12.5

- Supply will shift down (expand) by the expected dollar loss of $12.5, since firms are risk neutral.

- Demand will shift down (contract) by more than $12.5, since consumers are risk averse.

- The new market equilibrium is at point B (next slide). Price and quantity both fall. Quantity falls since the demand shift is more than the supply shift. (If both parties were risk neutral, price would still fall, but quantity would remain the same since the size of the shifts would be equal.)

Exercise Solutions

Lecture 14

By umich

Lecture 14

- 549