Applied

Microeconomics

Lecture 20

BE 300

Plan for Today

Go over "Pricing Games" case

Entry deterrence

Price Discrimination

Coming Up

Ch 10 intro and 10.1-10.2

Article: "Uber’s Surge Pricing is Totally Logical and Fair. So Why Do People Hate it So Much?"

Antitrust and Oligopoly in the News

From NYTimes (Hat tip Shreya Bhatia):

"The $70 billion combination of Kraft and Heinz is a big, big deal..."

"Both companies are in the packaged food business, so antitrust issues may arise in this transaction. Heinz has agreed to take all steps to clear the transaction with the antitrust authorities, including divestitures, except as would have a “material adverse effect” on the combined company. "

Reading the Fine Print in the Heinz-Kraft Deal NYT March 2015

- Examples: Both own pickle companies (will have to sell off one to competitor)

- Even though the resulting company will be big, regulators are not concerned about size: "protect competition, not competitors"

Antitrust and Oligopoly in the News

From NYT (hat tip Alex Taylor):

"Over the last year, oil prices have dropped by more than 50 percent. Motorists filling up at their local gas stations know that prices at the pump have dropped precipitously.

But consumers who have logged on to Expedia or Priceline or Kayak recently to book tickets saw that airfares had not dropped along with oil prices, an airline’s largest expense.

Why?"

As Oil Prices Fall, Airfares Still Stay High NYT March 2015

Antitrust and Oligopoly in the News

From NYT (continued):

"American Airlines, for example, doesn’t hedge its fuel costs, so it would arguably be well positioned to pick up business from its rivals. But it hasn’t tried.

...“The idea that U.S. airlines would, once again, devolve into a war for market share is founded on a misunderstanding of the new structure of U.S. airlines,” Vinay Bhaskara, an industry analyst, wrote in Airways News. “We are unquestionably living with an air travel oligopoly.”

...Such behavior is only possible either in an industry with very little competition or one in which members seem to actively avoid it.

As Oil Prices Fall, Airfares Still Stay High NYT March 2015

Antitrust and Oligopoly in the News

From NYT (continued):

The Justice Department sent a letter to Senator Schumer contending that the merger of American Airlines and US Airways — which it approved contingent upon some divestitures — has led to benefits for consumers through “lower prices and increased service.”

As Oil Prices Fall, Airfares Still Stay High NYT March 2015

Pricing Games

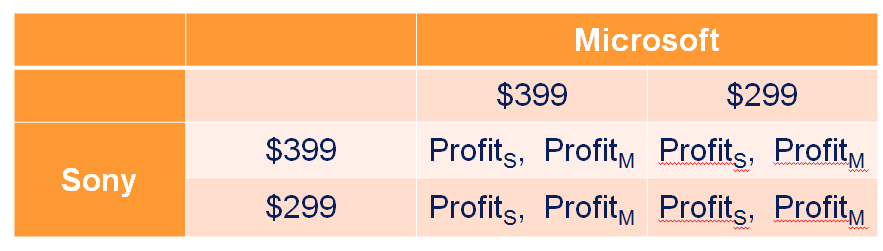

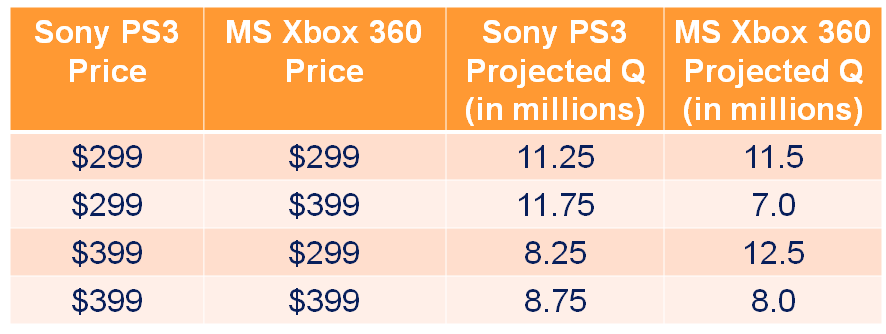

Q1: Given the information in Exhibits 1, 2, and 3, would you predict that Sony and/or Microsoft will want to reduce console prices by $100? You can assume Nintendo monitors its competitors’ actions, but has no plans to change its price in this short-run situation.

Pricing Games

Q1: Given the information in Exhibits 1, 2, and 3, would you predict that Sony and/or Microsoft will want to reduce console prices by $100? You can assume Nintendo monitors its competitors’ actions, but has no plans to change its price in this short-run situation.

Pricing Games

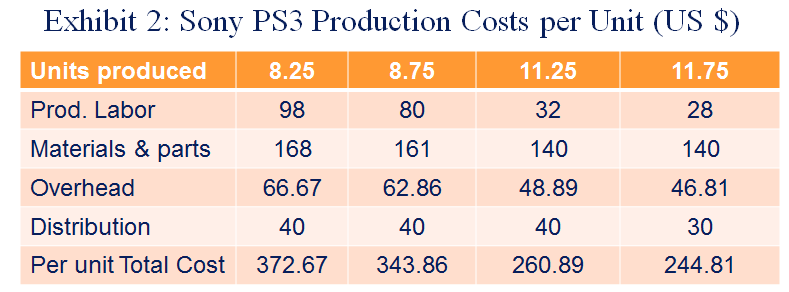

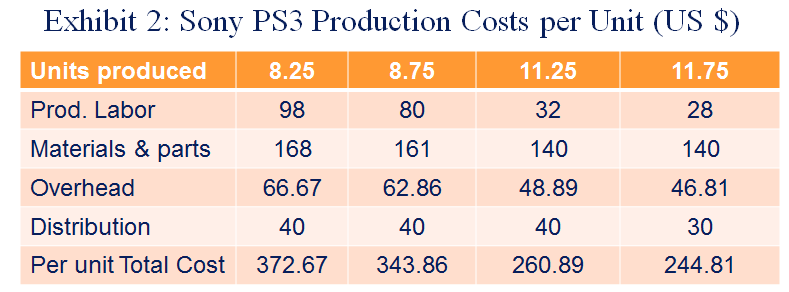

First: need to calculate payoffs. Since we're talking about the short term, we need to find the operating profit (i.e., excluding fixed costs that are sunk in the short run).

What information can you use to calculate these payoffs?

Pricing Games

Use Exhibit 1 to calculate total revenue.

Pricing Games

Short run decisions--fixed costs are "sunk." Which costs should we include in short-run profit?

Pricing Games

For each "box" in payoff matrix, use costs (from Exhibits 2 and 3) and quantities/revenue (from Exhibit 1) to calculate payoffs.

Pricing Games

Operating profit = revenue − variable cost

Variable cost = labor + materials & parts + distribution

E.g., Sony payoff when PS = $399 & PM = $399,

Sony’s Qs = 8.75

Variable cost per unit = 80 + 161 + 40 = $281

Operating profit contribution/unit = 399 – 281 = $118

Total oper. profit contribution = 118 * 8.75 = $1032.5 million

Pricing Games

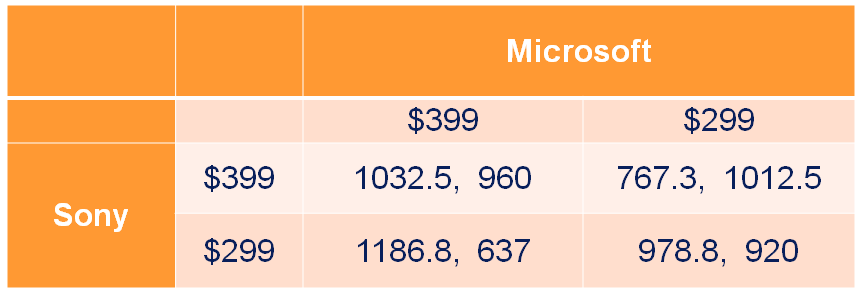

With some number crunching, you can arrive at:

So, what is each firm's dominant strategy? What is the Nash Equilibrium?

Pricing Games

Q2: Assume that demand curves are all linear. Calculate the own-price point elasticities of demand implied by the data at prices of $299 and $399 for both Sony and Microsoft.

A trick here is that you must be calculating the own-price elasticities off of a fixed demand curve. When Microsoft raises its price, what happens to the demand curve for Sony?

Pricing Games

Let's just do one--hold Microsoft's price fixed at $299 and calculate elasticity for Sony:

(∆Q/∆P)= (11.25–8.25)/(299–399) =–0.03

For Sony offering a price of $299:

elasticity is (-0.03) x (299/11.25) = -0.80

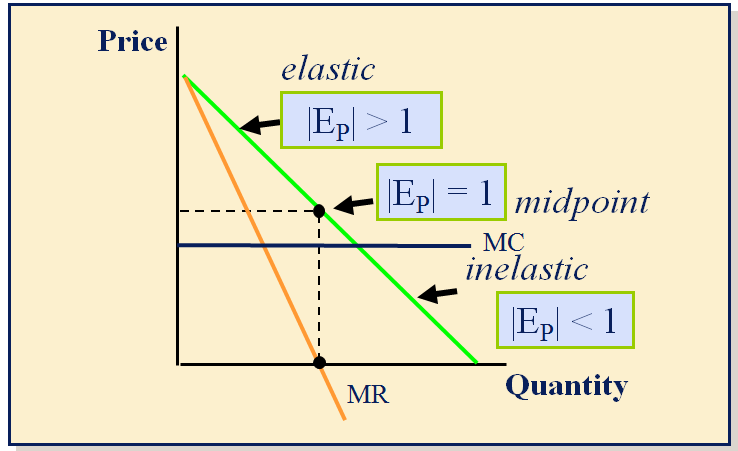

What is weird about this? Is this how a firm with market power is supposed to act?

Pricing Games

Firms that face downward sloping demand curves maximize profit by pricing where demand is elastic, not inelastic--what might be going on here? Are they just making a mistake by setting the price "too low"?

Oligopoly Market Strategy: Deterring Entry

If an incumbent in an industry is making a good profit, it will attract attention from possible entrants (unless protected by a patent). When faced with the possibility of other firms entering the market and competing away their profits, firms can either:

- Accommodate

- Fight

Oligopoly Market Strategy: Deterring Entry

Accommodate:

Entry is so attractive or easy that there is no strategy the incumbent(s) can implement at a reasonable cost to deter it.

There is no point wasting resources trying to prevent entry in this case!

Oligopoly Market Strategy: Deterring Entry

When strategy can deter entry: Fight

- Market conditions are such that entry is likely to occur, but actions taken by the incumbent(s) can deter entry, and it is profitable to do so

Predatory Pricing

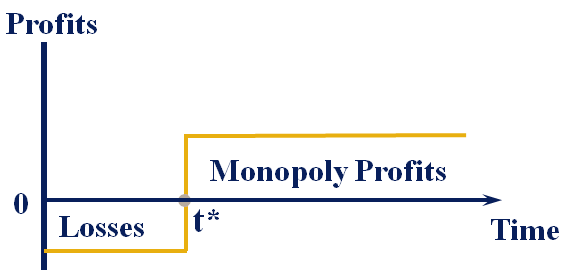

Predatory Pricing: Highly aggressive strategy; drop price and incur short-run losses. Rival leaves industry, is scared to enter, or is better behaved in the future. Then, raise price to recoup losses.

Predatory Pricing

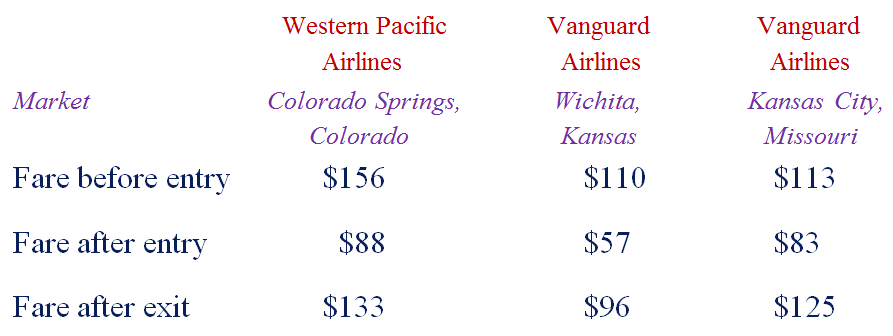

Average American Airlines one-way nonstop fares

between Dallas and three markets in mid-1990s

Predatory Pricing

Case filed 1999. First predatory pricing action brought against airlines by U.S. government.

Case dismissed April 2001 by District Court (KS)

- Judge said: “There is no doubt that American may be a difficult, vigorous, even brutal competitor. But here, it engaged only in bare, but not brass, knuckle competition.”

- AA’s behavior was not illegal because they had not set fares below AVC

AA said it was simply responding to market forces by lowering prices and increasing the number of flight

Dept. of Justice appealed decision; DOJ lost, again (10th Circuit, 2003)

Predatory Pricing

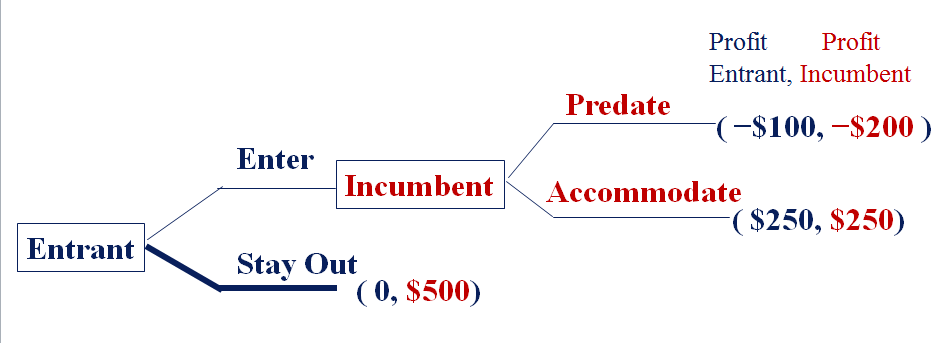

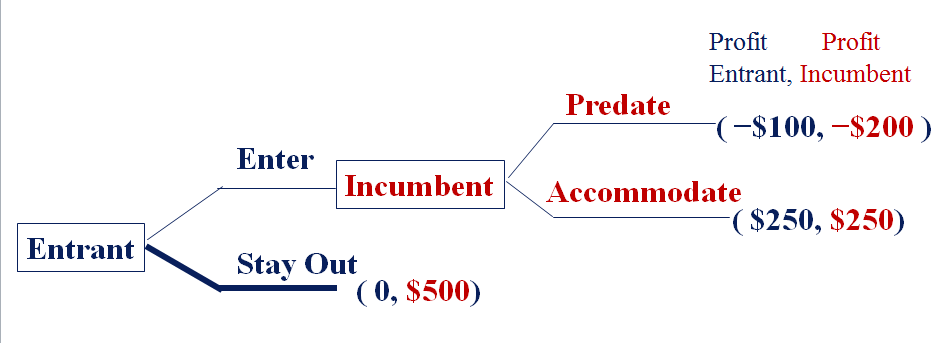

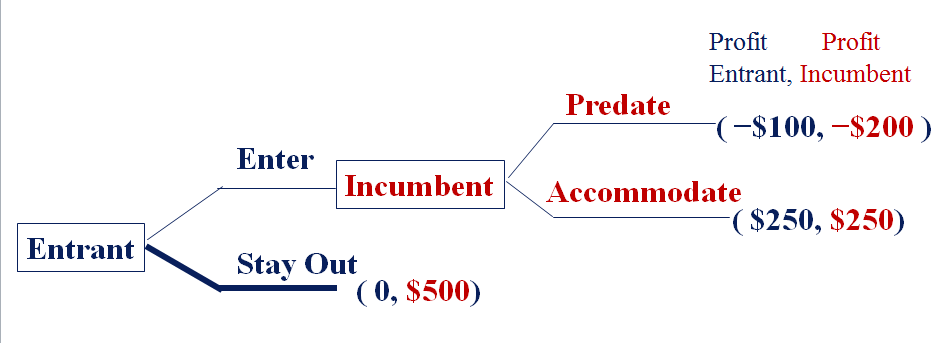

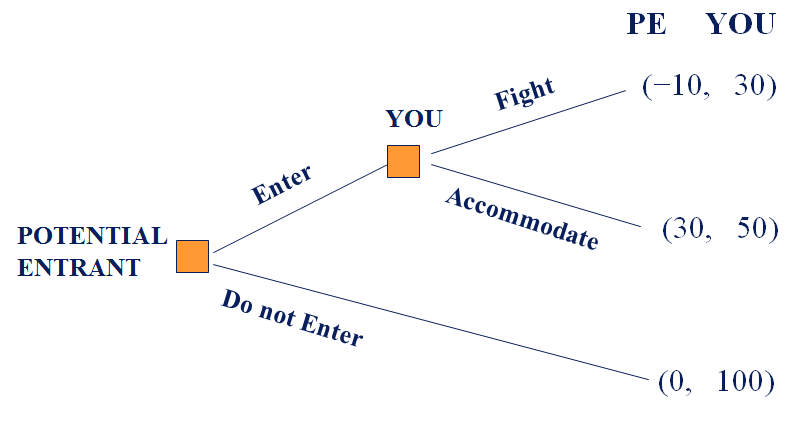

Assume this includes all (discounted) future profits in the payoffs. Is the threat to engage in predatory pricing credible? Reason backwards...

Predatory Pricing

What's the incumbent's best choice? Given this, what should the entrant choose?

Predatory Pricing

What if the payoffs to the incumbent for predatory pricing were $260 instead of -$200?

Predatory Pricing

These cases come under monopolization law need to show: (a) firm possesses “significant market power” and (b) firm “willfully acquired or maintained this power.” U.S. courts focus on specific elements of predatory pricing strategy:

- P < AVC (or MC)

- Specific intent to drive rival out

- Likelihood of recouping losses (“dangerous probability of success”). Note that this implies that the price cut must be temporary.

American Airlines CEO Bob Crandall: “If you’re not going to get them out then [there is] no point to diminish profits.” (U.S. v. AMR, Memorandum and Order, April 2001, http://www.justice.gov/atr/cases/f8100/8134.htm)

Oligopoly Market Strategy: Deterring Entry

Can a firm raise rivals’ costs before entry occurs in such a way as to increase its own profits?

Suppose (as a worst case scenario) a firm raises everyone’s costs of competing, including their own:

- The direct effect on profits is negative (since costs rise)

- But there can be a positive strategic effect if rivals’ profits or expected profits are affected even more (i.e., rivals either exit or don’t enter and incumbent’s profits rise on net).

Raising Costs

“Sunk costs” are non-recoverable costs that must be incurred to enter a market.

How can sunk costs help prevent entry?

Example — consider a new product that can generate the following operating profits:

- Monopoly operating profits = 100K

- Duopoly operating profits = 40K each (80K total)

Raising Costs

“Sunk costs” are non-recoverable costs that must be incurred to enter a market.

Example — consider a new product that can generate the following operating profits:

- Monopoly operating profits = 100K

- Duopoly operating profits = 40K each (80K total)

Raising Costs

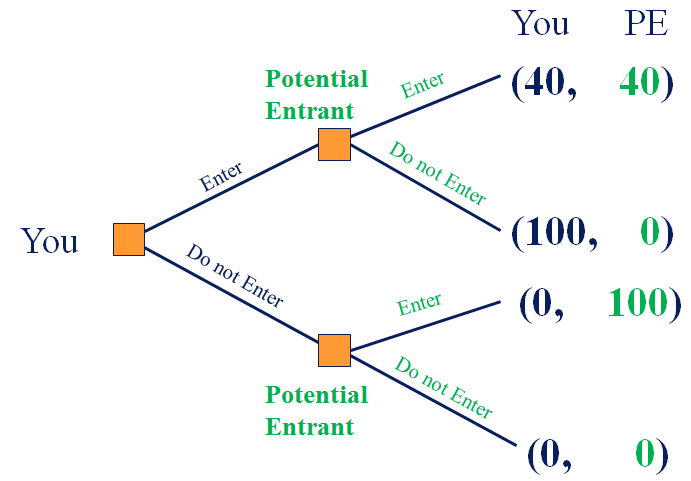

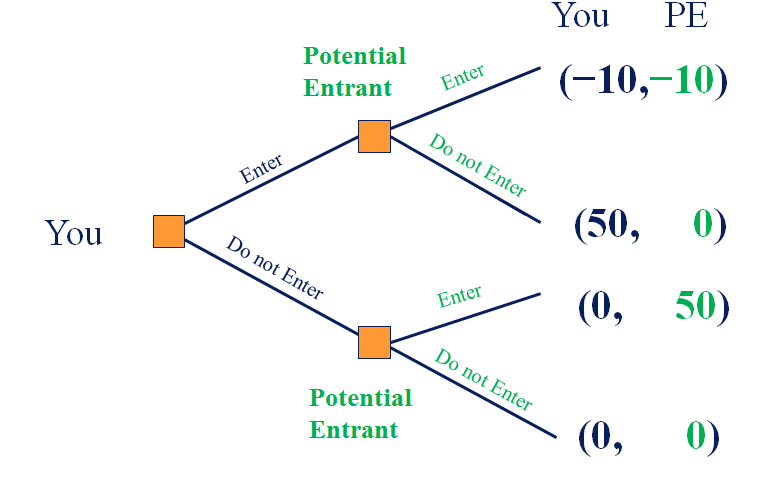

Suppose you came up with the idea for a product, so you get to go “first” and decide whether to enter, but then an entrant can possibly enter as well and compete with you.

•Scenario A: There are no sunk costs to develop the product.

•Scenario B: Each firm (including yourself) has to pay 50K in sunk setup costs to develop the product.

Which scenario would you prefer?

Raising Costs

A world with no sunk costs. What happens?

Raising Costs

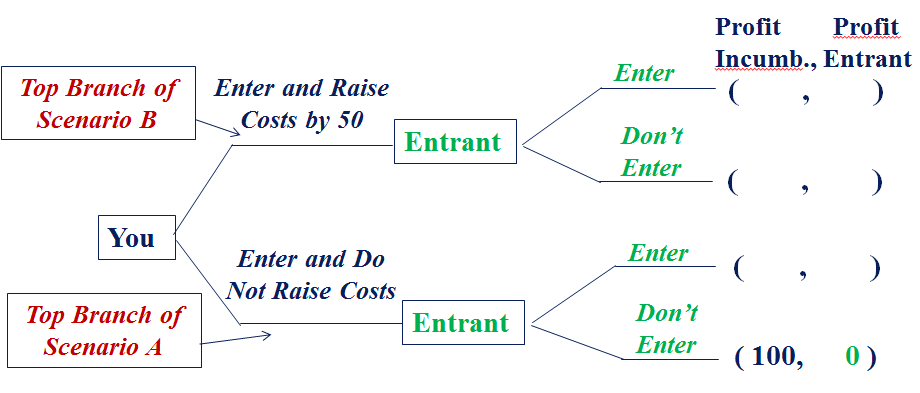

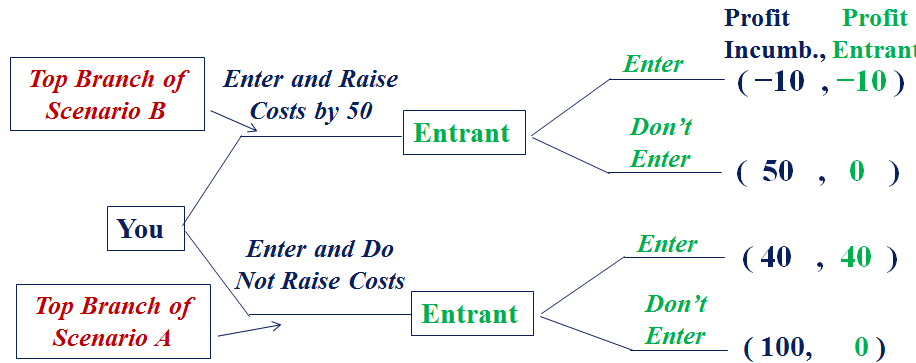

Now everyone needs to pay $50 to develop the product. What happens? Which is better for you?

Raising Costs

Point is: that sunk costs end up actually increasing your equilibrium profits because they prevent the entrant from entering and competing with you.

But what if these sunk costs don’t exist for your product?

The main idea is that you may be able to “create” these sunk costs through your actions. These are sometimes called “endogenous” sunk costs.

Raising Costs

For example, suppose that you can invest a large sum of money in new technology that will significantly decrease your marginal costs of production.

Suppose this investment is not cost effective in a world where there is no entry, i.e., the marginal cost decreases are not big enough to justify the costs of the new technology.

However, under threat of entry, this investment might be worthwhile, even though it is not cost effective.

Raising Costs

Why? The investment creates an “endogenous sunk cost” that the entrant will need to incur in order to compete with you (otherwise, they would have much higher marginal costs). As we just saw in our game tree, this sunk cost can make entry less likely.

Advertising or investments in product quality can also be used as endogenous sunk costs to deter entry. For example, if you as the initial entrant advertise large amounts, it will be harder for a potential entrant to enter the market.

Suppose you have the option to create an endogenous sunk cost of 50K

Raising Costs

What would be the maximum the monopolist is wiling to pay to deter entry? What is the maximum the entrant is willing to pay to access the market?

Raising Costs

Monopolist earns $60 more if the entrant stays out.

But entrant only gets $40 for entering. This asymmetry creates the opportunity to deter entry.

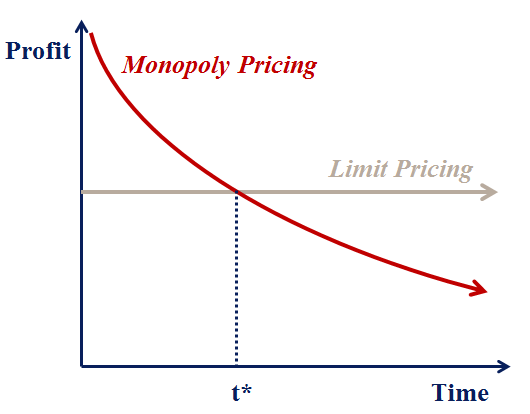

Limit Pricing

Suppose you are the only firm in a market. Optimal pricing suggests that you should charge the monopoly price/quantity, i.e., set Q where MR=MC (then price off the demand curve).

Limit pricing involves pricing LESS than the profit maximizing monopoly price even before entry occurs.

This lowered pricing obviously sacrifices some current profits, but it can potentially keep entrants out. Why?

Limit Pricing

1) Lower prices can make potential entrants think that you have lower costs than you actually do.

2) Lower prices can make potential entrants think that demand conditions (and thus profitability) are worse than they actually are.

3) Lower prices make it hard for potential entrants to quickly gain market share from you.

These all make entry look less attractive to potential entrants.

Limit Pricing

The trade off of limit pricing: lower short run profits, higher long run profits. Is it worth it? It depends. (Existing barriers to entry, discount factor, probability of entry, how low price needs to be to deter entry, etc).

Capacity Expansion

Suppose you are a monopolist selling a product at reasonably high prices and making 100K/year profits.

You learn of a new potential entrant into your market. To enter, the entrant would pay a fixed cost of entry and then compete with you. You worry about the impacts on your profitability.

Suppose capacity constraints are important in this industry.

Capacity Expansion

As we’ve been discussing, you consider two possible strategies to take if entry does occur:

Accommodate entry — keep prices relatively high, preserving some profits but letting the entrant obtain a significant market share. Suppose you anticipate that this strategy will give you profits = 50K;

Fight entry — dramatically increase production and lower prices, sacrificing profits but causing the entrant to make losses. But, it will cost you 30K to obtain the extra capacity. Including the cost of this capacity investment, you anticipate that this strategy will give you overall profits = 30K.

Capacity Expansion

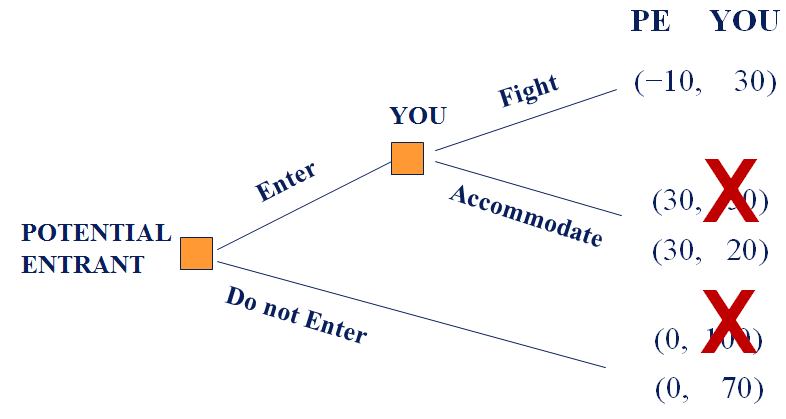

Note: the 30 profit following Enter -> Fight takes into account the 30 investment in capacity cost.

What's the problem here? What's the equilibrium of this game (i.e., what's going to happen)?

Capacity Expansion

You would like to commit to fighting entry, but this is not a “credible” threat.

What can you do to change this outcome?

Capacity Expansion

•Suppose you think ahead a bit and consider the possibility of investing in extra capacity (in order to price low and fight entry) before the entrant has a chance to enter. Recall that this excess capacity costs 30K.

•In this case, you incur the 30K cost even if the entrant doesn’t enter, or if the entrant enters and you accommodate. You always pay the 30K -- this is visible and the entrant knows it.

•What happens to payoffs in the game tree?

Capacity Expansion

Now: you're always ready to fight!

Lowers profits but threat becomes credible.

Does the entrant enter? What is the new equilibrium?

Capacity Expansion

By investing in extra capacity early, you are in essence committing to price cutting if the entrant enters. This prevents the entrant from entering in the first place.

Might seem crazy to lower profits from 100 to 70 --but there could be a strategic reason.

Game Theory

"Game theory must not be used actually to ‘solve’ the game and produce a numerical answer. The reason for this is that the solutions to the games are often too sensitive to the assumptions that the modeler makes about the timing of the moves, the information available to the players and the rationality of their decisions...

Instead, game theory's greatest use is in obtaining insights about the structure of interaction between the players, not only to learn what is the right way to play the game, but also to understand existing possibilities and consequences of changing game rules."

Garicano, “Game Theory: How to Make it Pay”

Lecture 20

By umich

Lecture 20

- 727