Politics through the Lens of Economics

Lecture 4: Citizen-candidate Model

Masayuki Kudamatsu

25 October, 2017

Did everyone pick a policy?

For your term paper...

Start thinking (or even writing)

about whether

the Median Voter Theorem

can explain the failure to adopt

the policy of your choice

For your term paper...

Take note of the source of information

Image source: xkcd.com/285/

For your term paper...

& follow Harvard referencing

Discussion Time

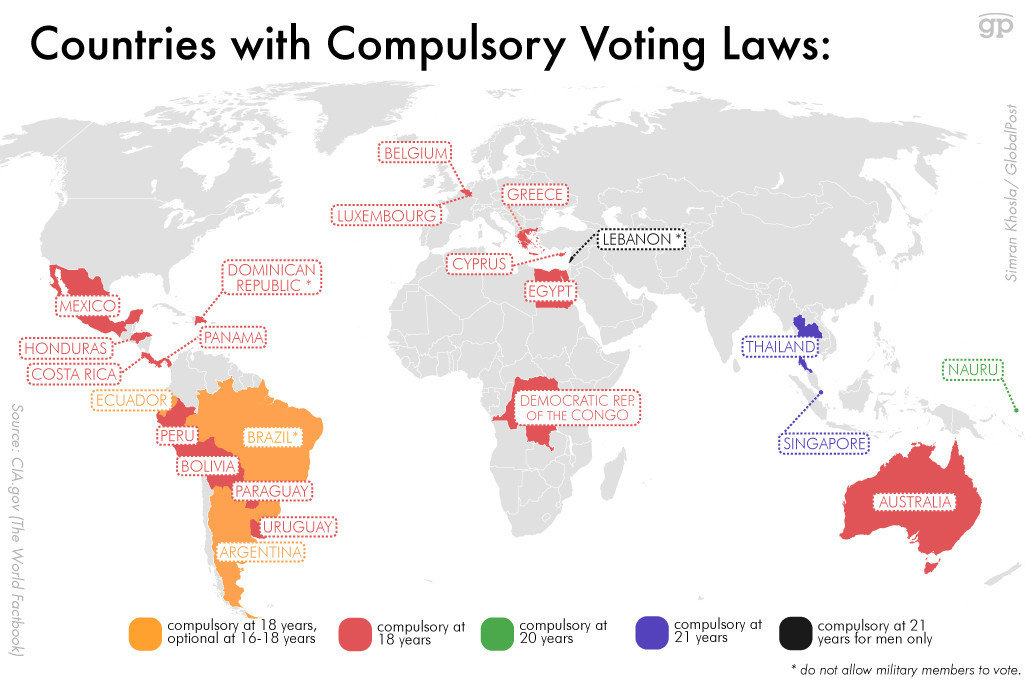

Does the Median Voter Theorem explain

why voting is not compulsory in Japan?

Remember when a model can explain reality?

Source: CIA World Factbook (for data), www.pri.org/stories/2014-10-14/map-shows-all-countries-where-voting-mandatory (for image)

Background for discussion

Arguments in favor of compulsory voting

Source: Wikipedia

Higher legitimacy of the elected goverment

Exclusion of other voters cannot be the best strategy for politicians

Background for discussion

Waleed Aly (political scientist)

Make citizens learn about politics

Less money spent in elections

Reduce the influence of external factors such as weather and transport

Arguments against compulsory voting

Source: Wikipedia

Infringement of freedom of speech

Uninformed voters may become decisive

Background for discussion

Discussion Time

Does the Median Voter Theorem explain

why voting is not compulsory in Japan?

Remember

your aim is

to come up with

a wrong answer

Today's Road Map

Citizen-candidate Model

Testing the commitment assumption

Today's Economics Lessons

Citizen-candidate Model

Testing the commitment assumption

Multiple Equilibria

Regression Discontinuity Design

Today's Road Map

Citizen-candidate Model

Testing the commitment assumption

Motivations

Two restrictive assumptions

in the Median Voter Theorem

1. Commitment to electoral promise by politicians

2. Only two candidates compete in election

Citizen-candidate model

Assumes no commitment

Analyzes a citizen's decision to become a candidate

Consider a model of the world where

Step 1: Each citizen decides whether to run for office

Image source: www.city.hachioji.tokyo.jp/faq/27680/027703.html

Citizen-Candidate Model

Running for office is costly

Image source: www.city.hachioji.tokyo.jp/faq/27680/027703.html

Consider a model of the world where

Citizen-Candidate Model

Step 2: Each citizen decides whom to vote

Image source: www.town.nogi.lg.jp/page/page000208.html

Consider a model of the world where

Citizen-Candidate Model

Candidate wins by plurality

Consider a model of the world where

Citizen-Candidate Model

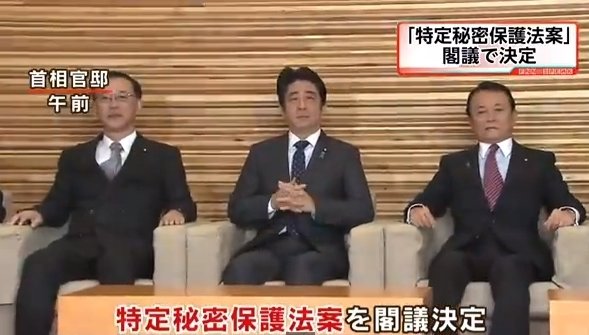

Step 3: Winning candidate picks a policy to implement

Image source: saigaijyouhou.com/blog-entry-1098.html

Consider a model of the world where

Citizen-Candidate Model

Step 3: Winning candidate picks a policy to implement

Step 2: Each citizen decides whom to vote

Step 1: Each citizen decides whether to run for office

Running for office is costly

Candidate wins by plurarity

Consider a model of the world where

Citizen-Candidate Model

Let's consider optimization at each step

Step 3: Winning candidate picks a policy to implement

Step 2: Each citizen decides whom to vote

Step 1: Each citizen decides whether to run for office

Running for office is costly

Candidate wins by plurarity

Winning candidate's optimization in step 3:

Pick his/her own ideal policy

Image source: sayuflatmound.com/?p=19482

Let's consider optimization at each step

Step 3: Winning candidate picks a policy to implement

Step 2: Each citizen decides whom to vote

Step 1: Each citizen decides whether to run for office

Running for office is costly

Candidate wins by plurarity

Citizen's optimization in step 2 (voting):

Vote the candidate whose ideal policy is closest

unless there are three or more candidates (we see this later)

Remember Lecture 2 ?

Let's consider optimization at each step

Step 3: Winning candidate picks a policy to implement

Step 2: Each citizen decides whom to vote

Step 1: Each citizen decides whether to run for office

Running for office is costly

Candidate wins by plurarity

Citizen's optimization in step 1 (running for office):

Depends on

who else is running for office

Use the concept of equilibrium in such a case

In an equilibrium:

Each candidate

wants to run for office

No other citizen

wants to run for office

Each candidate

wants to run for office

No other citizen

wants to run for office

We now check whether these two equilibrium conditions hold when:

One candidate runs unopposed

Two candidates compete

One candidate runs unopposed

Each candidate

wants to run for office

No other citizen

wants to run for office

If the only candidate's ideal policy is not median

A citizen whose ideal policy is closer to median can win

Each candidate

wants to run for office

No other citizen

wants to run for office

If the only candidate's ideal policy is median

Median candidate can win and implement his/her ideal policy

One candidate runs unopposed

Each candidate

wants to run for office

No other citizen

wants to run for office

If the only candidate's ideal policy is median

Any non-median citizen cannot win

Another median citizen doesn't have to run to implement median policy

One candidate runs unopposed

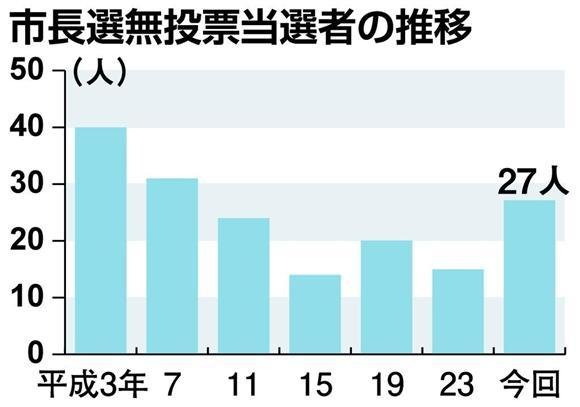

One-candidate equilibrium

The same prediction as the Median Voter Theorem

runs for office

wins the election

implements the median policy

One median citizen

It does happen in reality that one candidate runs unopposed

27

Two candidates compete

Each candidate

wants to run for office

No other citizen

wants to run for office

If each candidate's ideal policy is not symmetrical around median

The candidate farther away from median cannot win

Each candidate

wants to run for office

No other citizen

wants to run for office

If each candidate's ideal policy is symmetrical around median

Each candidate faces a 50% chance of winning

Two candidates compete

Each candidate

wants to run for office

No other citizen

wants to run for office

If each candidate's ideal policy is symmetrical around median

No other citizen

can win

(not even median voter)

Two candidates compete

Why can't any other other citizen win (not even median voter) ?

Policy

Median

A

B

Vote for A

Vote for B

With symmetrical two candidates

each citizen votes for who's closer

Policy

A

B

Vote for A

Vote for B

C

Why can't any other other citizen win (not even median voter) ?

Median

Suppose C decides to run for office

Policy

A

B

Vote for A

Vote for B

C

Switch to vote for C ?

Why can't any other other citizen win (not even median voter) ?

Median

Does any citizen closest to C switch to vote for C?

Policy

Median

A

B

Vote for A

Vote for B

C

When every other citizen votes for either A or B,

Those closer to A:

Switching to vote for C makes B win

Vote for C

That's worse than both A and B have a 50% winning chance

Policy

Median

A

B

Vote for A

Vote for B

C

When every other citizen votes for either A or B,

Those closer to B:

Switching to vote for C makes A win

Vote for C

That's worse than both A and B have a 50% winning chance

Policy

Median

A

B

Vote for A

Vote for B

C

When every other citizen votes for either A or B,

Same is true even if candidate C is median

Vote for C

Policy

Median

A

B

Vote for A

Vote for B

C

So C cannot win any vote

(even if C is median)

Policy

Median

A

B

Vote for A

Vote for B

C

With three or more candidates,

citizens may not vote for the candidate whose ideal policy is closest

(called "strategic voting")

Policy

Median

A

B

Vote for A

Vote for B

Since C cannot win any vote

(even if C is median)

C doesn't want to run for office

Each candidate

wants to run for office

No other citizen

wants to run for office

If each candidate's ideal policy is symmetrical around median

No other citizen

can win

(not even median voter)

Two candidates compete

A different prediction from the Median Voter Theorem

Two-candidate equilibrium

Two citizens whose ideal policy is symmetric around median

runs for office

wins the election with a 50% chance

Winning candidate

implements his/her ideal policy

Citizen-candidate model can explain the two-party system

image source: www.vice.com/read/the-first-presidential-debate-decoded

Three or more candidate equilibria

Possible, but too technical to discuss

Multiple equilibria

A

B

A

B

Policy

A

Median

A

B

Today's economics lesson #1

Citizen-candidate model has many equilibria

Multiple equilibria

A

B

A

B

Policy

A

Median

A

B

Today's economics lesson #1

We cannot predict which equilibrium to emerge in reality

Osaka

Tokyo

Image source: www.nikkei.com/article/DGXLASIH02H08_T01C14A2AA1P00/

Today's economics lesson #1

Multiple equilibria

We cannot predict which equilibrium to emerge in reality

Osaka

Tokyo

Image source: www.nikkei.com/article/DGXLASIH02H08_T01C14A2AA1P00/

Today's economics lesson #1

Multiple equilibria

Once an equilibrium is achieved, it's difficult to move to another

Today's economics lesson #1

A model with multiple equilibria:

Cannot be tested against the data

Multiple equilibria

Theoretically insightful

But we can check if the model assumption is consistent with data

Today's Road Map

Citizen-candidate Model

Testing the commitment assumption

Crucial in the citizen-candidate model

cannot commit to electoral promise

choose their own ideal policy once elected

Politicians

Lots of anecdotes supporting this assumption

But does it stand against more systematic evidence?

The no-commitment assumption

Ideal experiment

For randomly picked half

of electoral districts

For the remaining half

Median voter's ideal policy: similar on average

Ideal experiment

For randomly picked half

of electoral districts

Let Party A's candidate win

For the remaining half

Let Party B's candidate win

Median voter's ideal policy: similar on average

Ideal experiment

For randomly picked half

of electoral districts

Let Party A's candidate win

For the remaining half

Let Party B's candidate win

Median voter's ideal policy: similar on average

Winner's chosen policy: similar on average

if politicians can commit to electoral promise

Ideal experiment

For randomly picked half

of electoral districts

Let Party A's candidate win

For the remaining half

Let Party B's candidate win

Median voter's ideal policy: similar on average

if politicians cannot commit to electoral promise

A's ideal policy chosen

B's ideal policy chosen

Ideal experiment

For randomly picked half

of electoral districts

Let Party A's candidate win

For the remaining half

Let Party B's candidate win

Median voter's ideal policy: similar on average

But this is impossible!

Ideal experiment

For randomly picked half

of electoral districts

Let Party A's candidate win

For the remaining half

Let Party B's candidate win

Median voter's ideal policy: similar on average

Where does something similar to this

happen in reality?

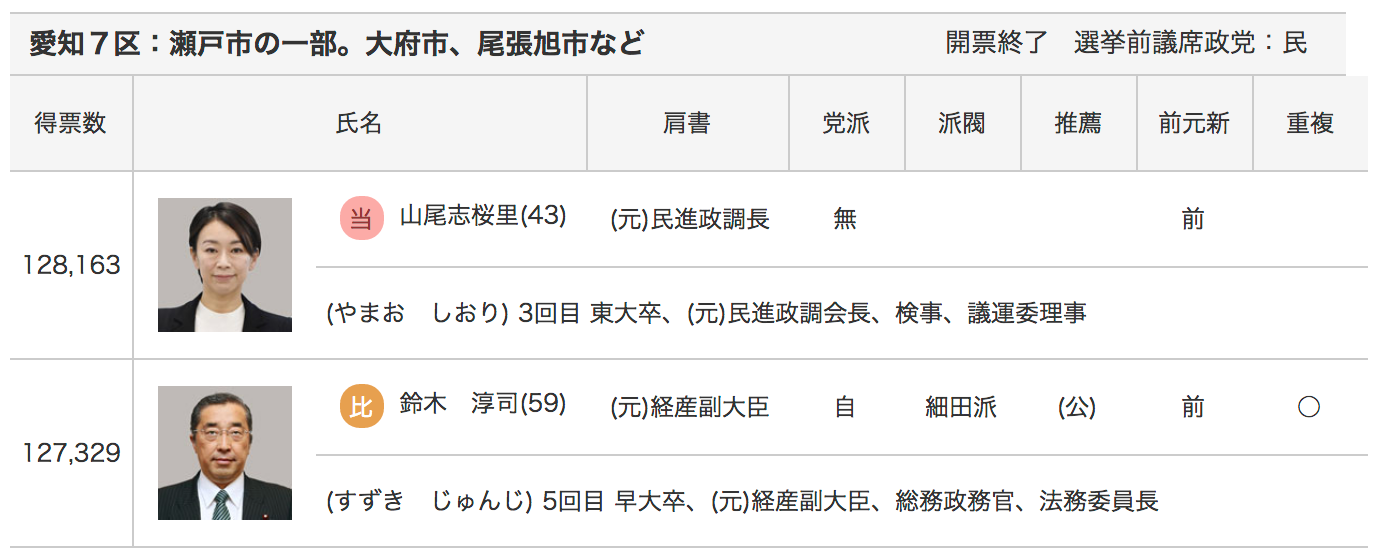

e.g. Aichi 7th district at the 2017 Lower House Election in Japan

Image source: https://www.nikkei.com/2017shuin/kaihyo/pref/?pref=23

Close elections

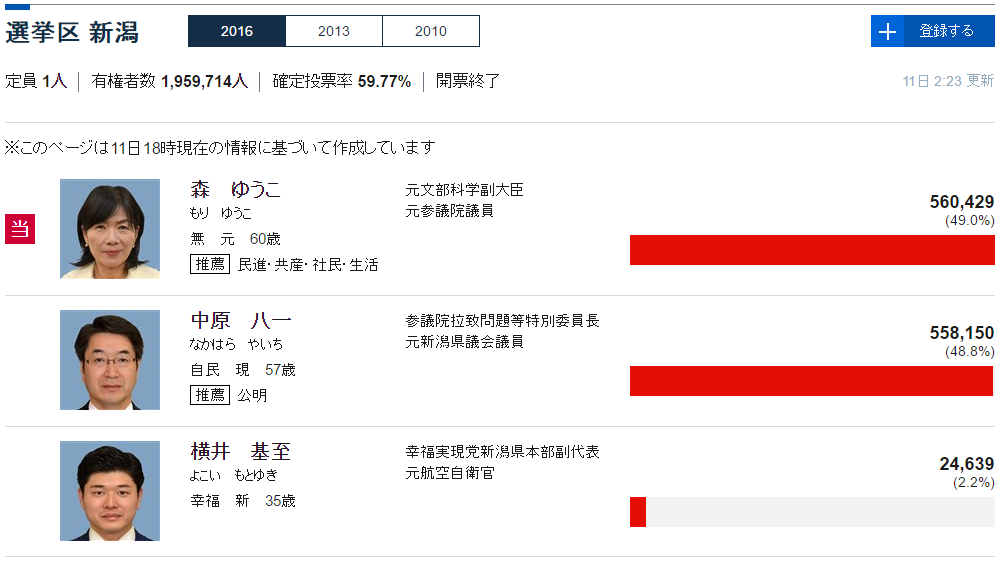

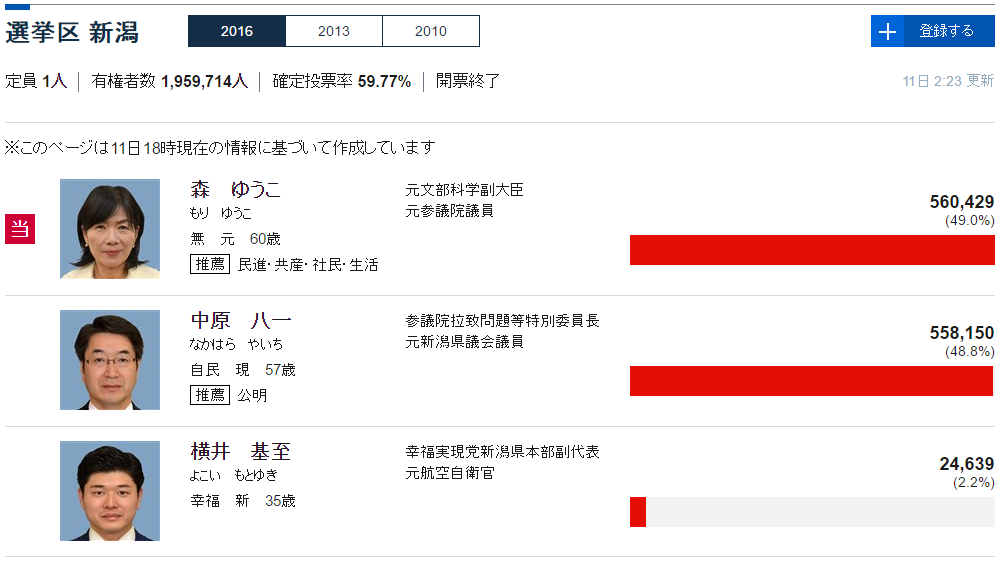

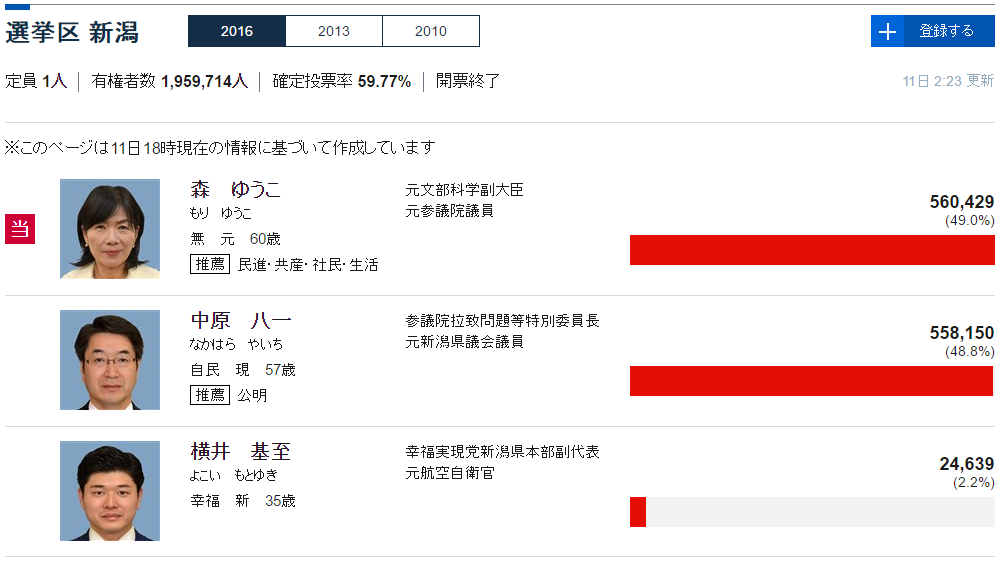

e.g. Niigata district at the 2016 Upper House Election in Japan

Close elections

e.g. Oita district at the 2016 Upper House Election in Japan

Close elections

Which of the top two candidates won was plausibly random

Close elections

Regression Discontinuity Design

exploits these election

Today's Economics Lesson #2

Regression Discontinuity Design

e.g., Impact of admission to Osaka University

Exam score

Admitted

Not admitted

For these students

it's random

whether admitted or not

Today's Economics Lesson #2

Regression Discontinuity Design

e.g., Impact of representative vs direct democracy

population

Representative

Direct

For these municipalities

it's random

whether direct or not

(in Swedish municipalities in 1919)

1,500

Today's Economics Lesson #2

Regression Discontinuity Design

Then plot the outcome against exam score or population

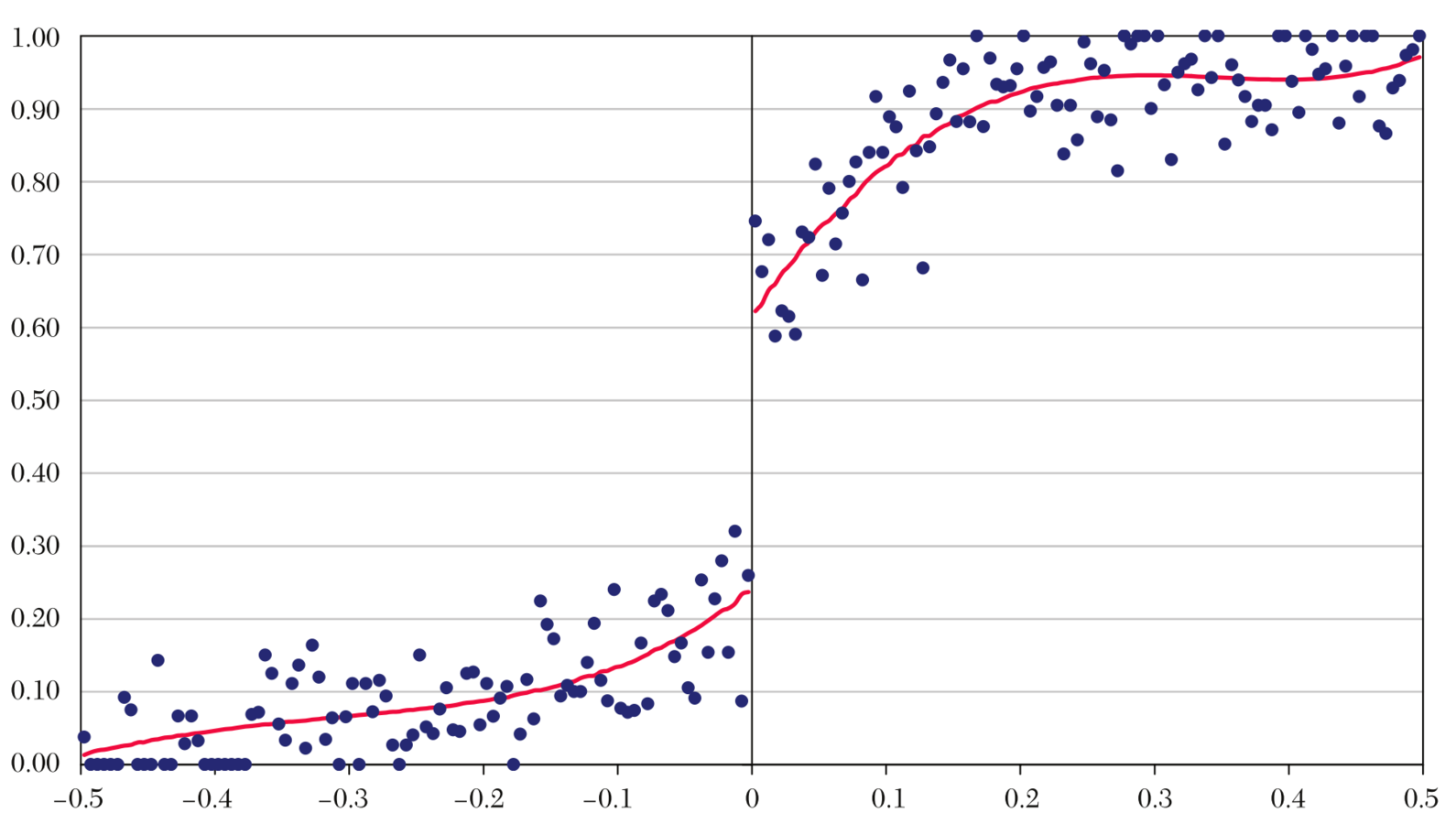

Image Source: Figure 8 of Lee and Lemieux (2010)

Bin average

Predicted value

Impact

Today's Economics Lesson #2

Regression Discontinuity Design

Then plot the outcome against exam score or population

Image Source: Figure 11 of Lee and Lemieux (2010)

Impact

Today's Economics Lesson #2

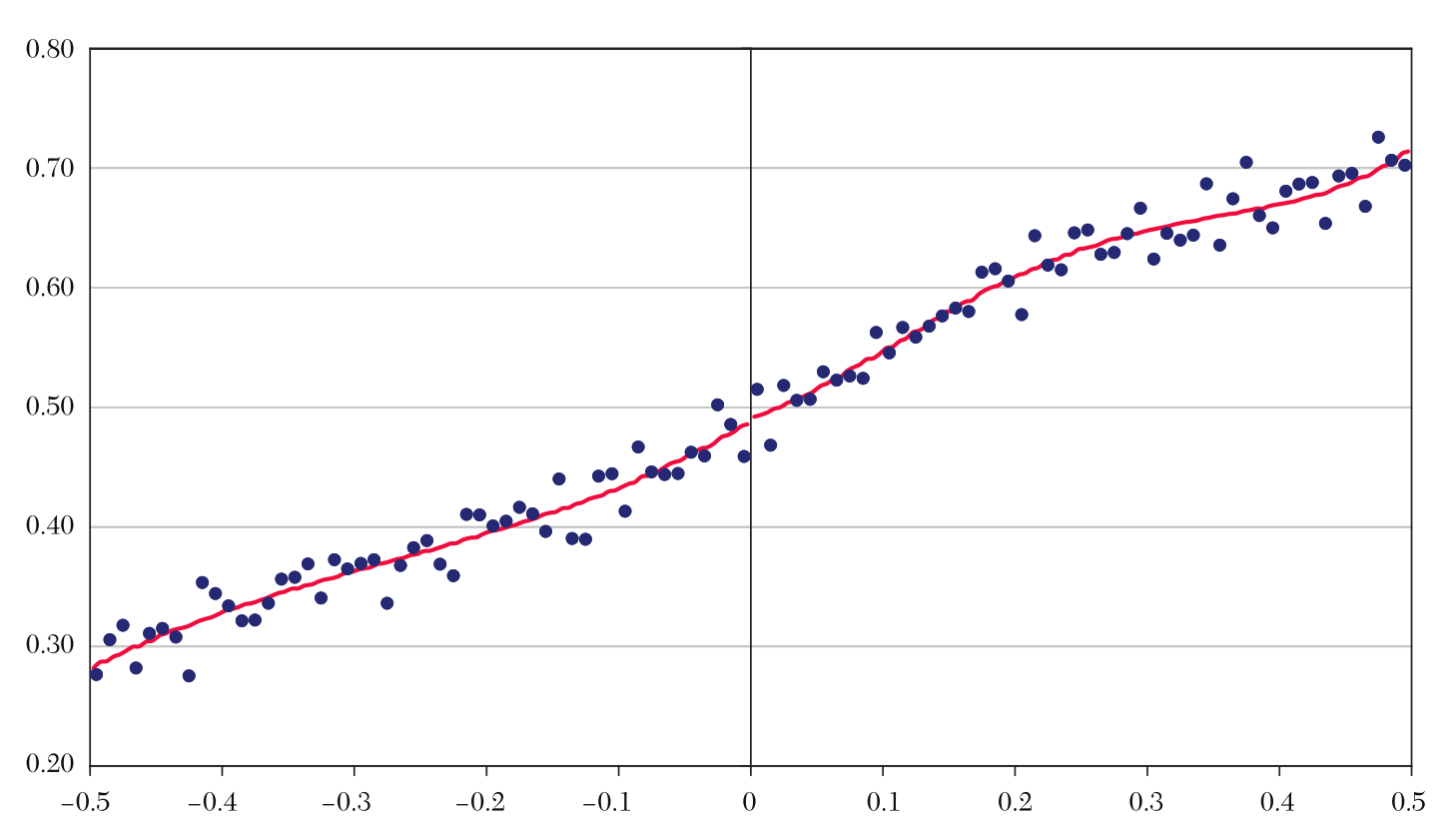

Regression Discontinuity Design

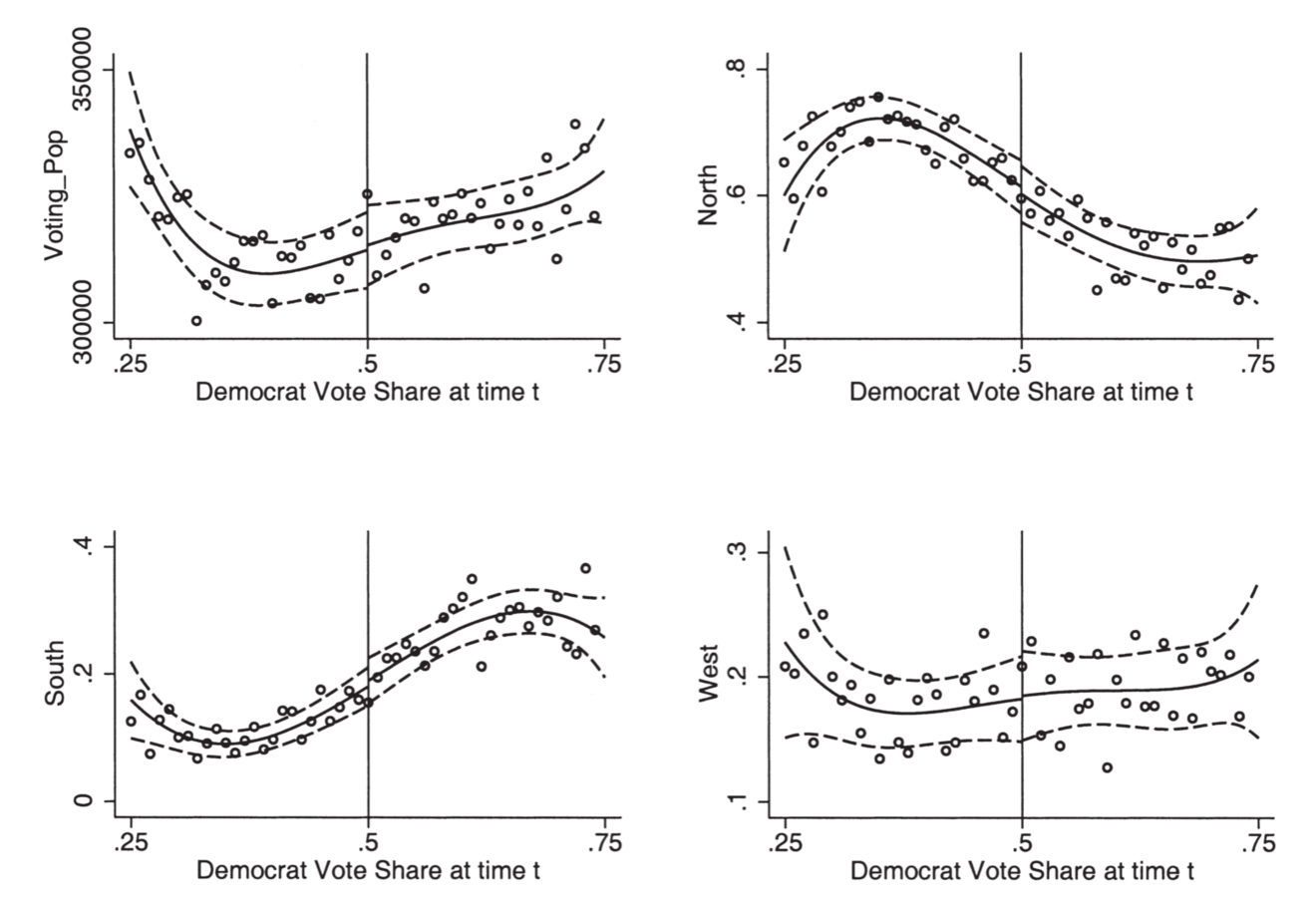

Also plot irrelevant characteristics to check randomness

Image Source: Figure 17 of Lee and Lemieux (2010)

No difference

Today's Economics Lesson #2

Regression Discontinuity Design

Image Source: Figure 16 of Lee and Lemieux (2010)

Insignificant

difference

Also plot irrelevant characteristics to check randomness

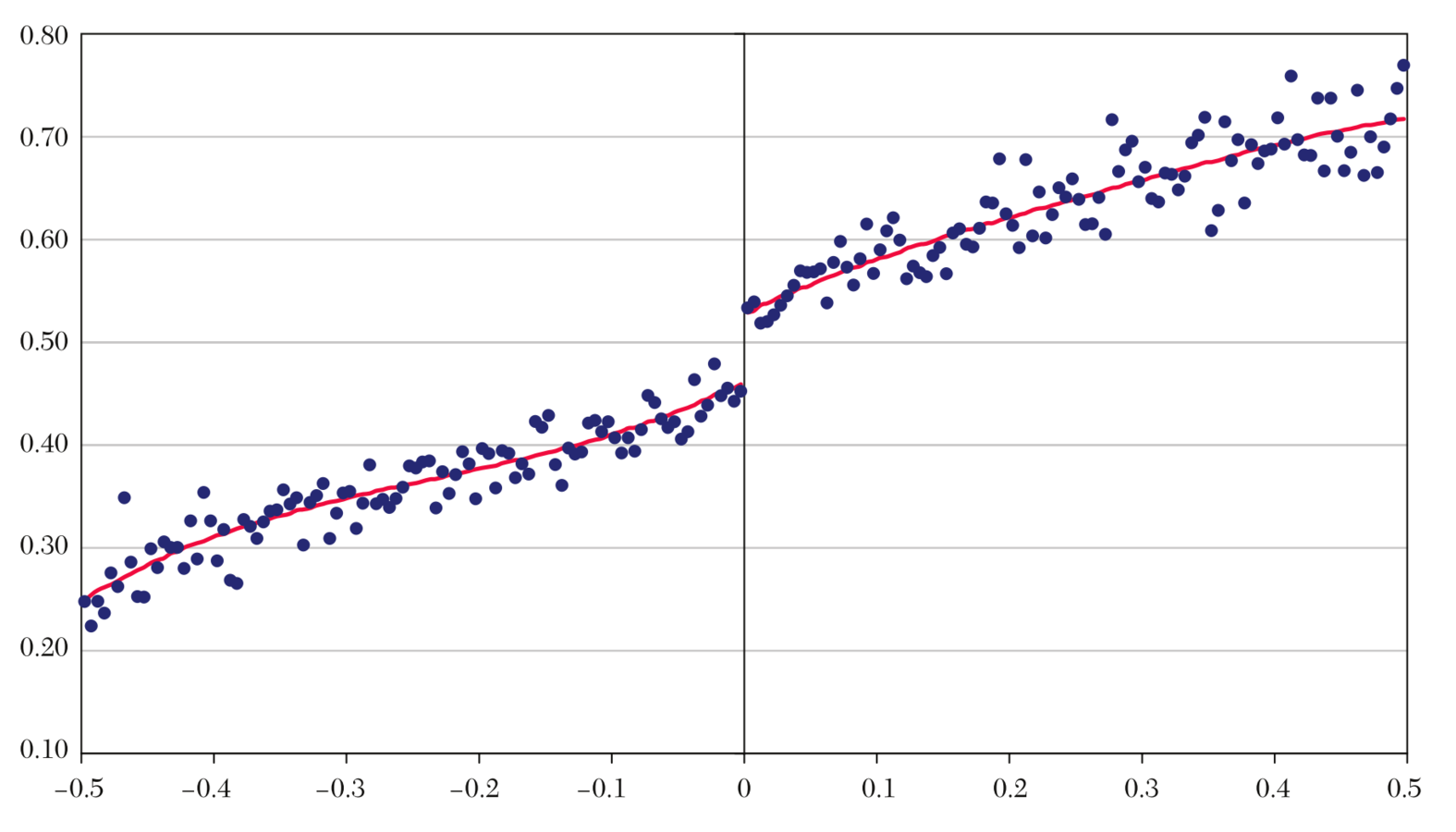

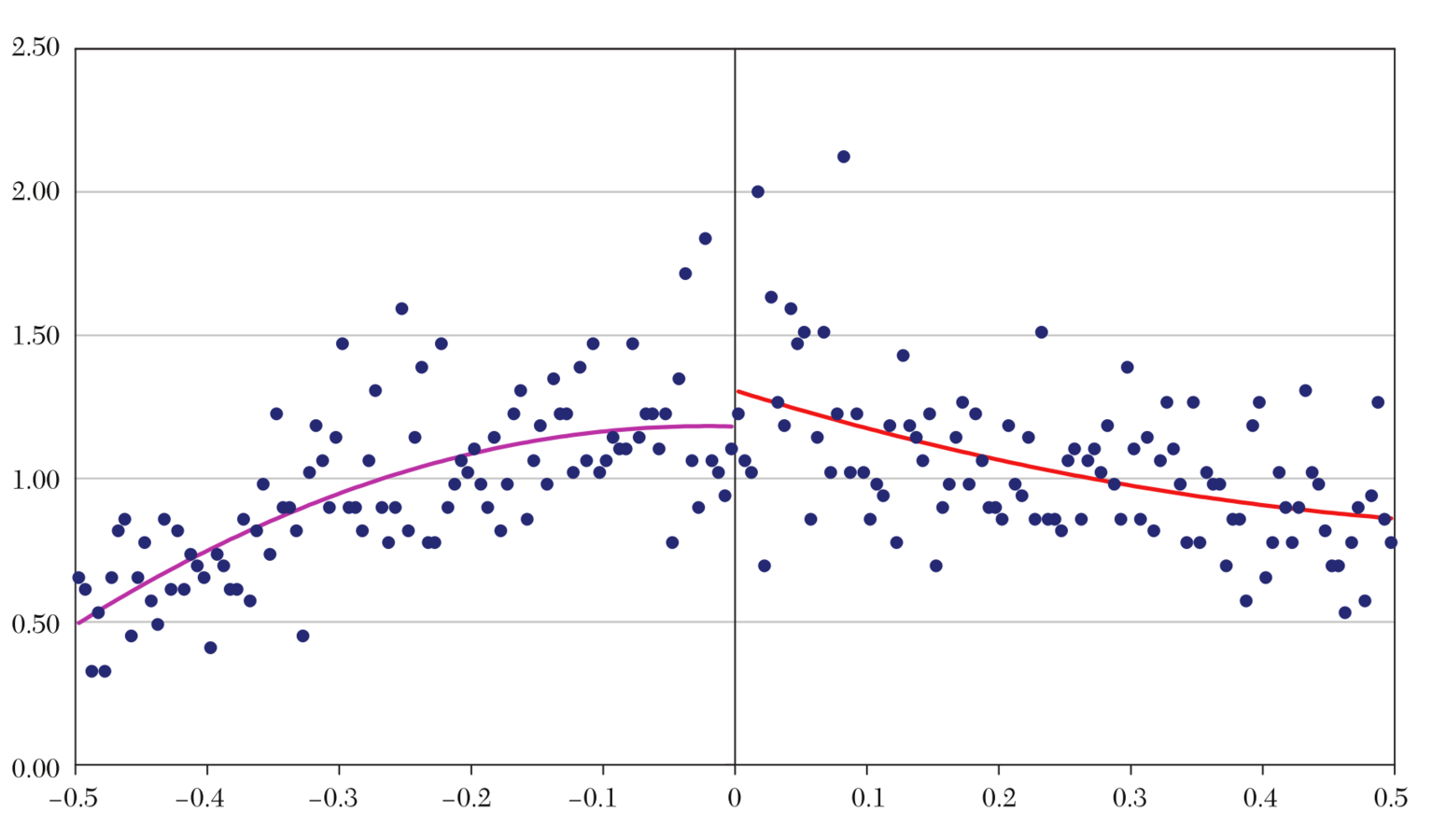

Take this idea to US Lower House Elections, 1946-1994

Plot outcomes against Democratic Party's candidate vote share

Vote share (%)

100

50

0

If who wins is random in close elections, districts around 50% vote share should be similar

Testing the no-commitment assumption

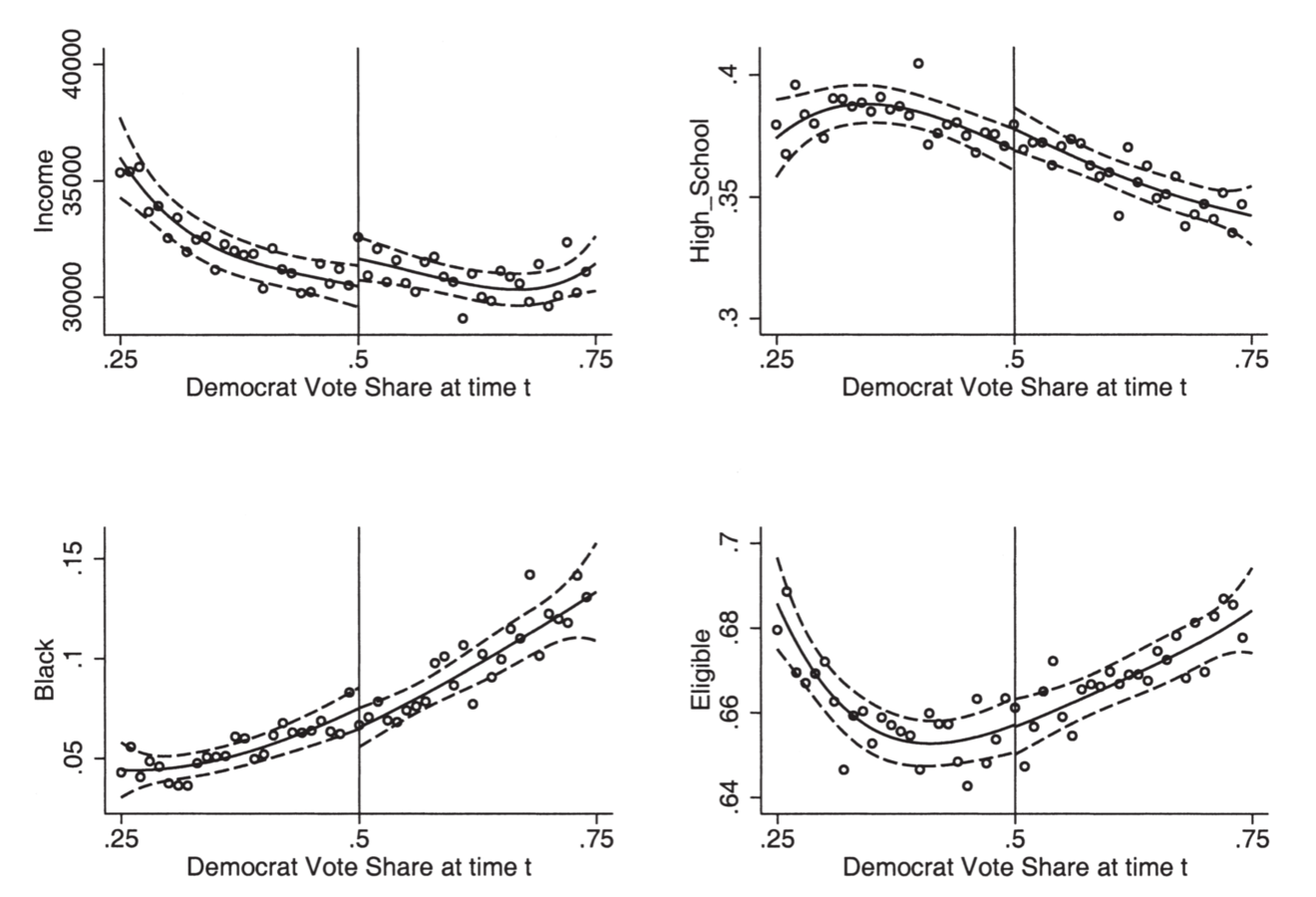

Districts around 50% vote share are indeed similar

Source: Figure 3 of Lee et al. (2004)

Districts around 50% vote share are indeed similar

Source: Figure 4 of Lee et al. (2004)

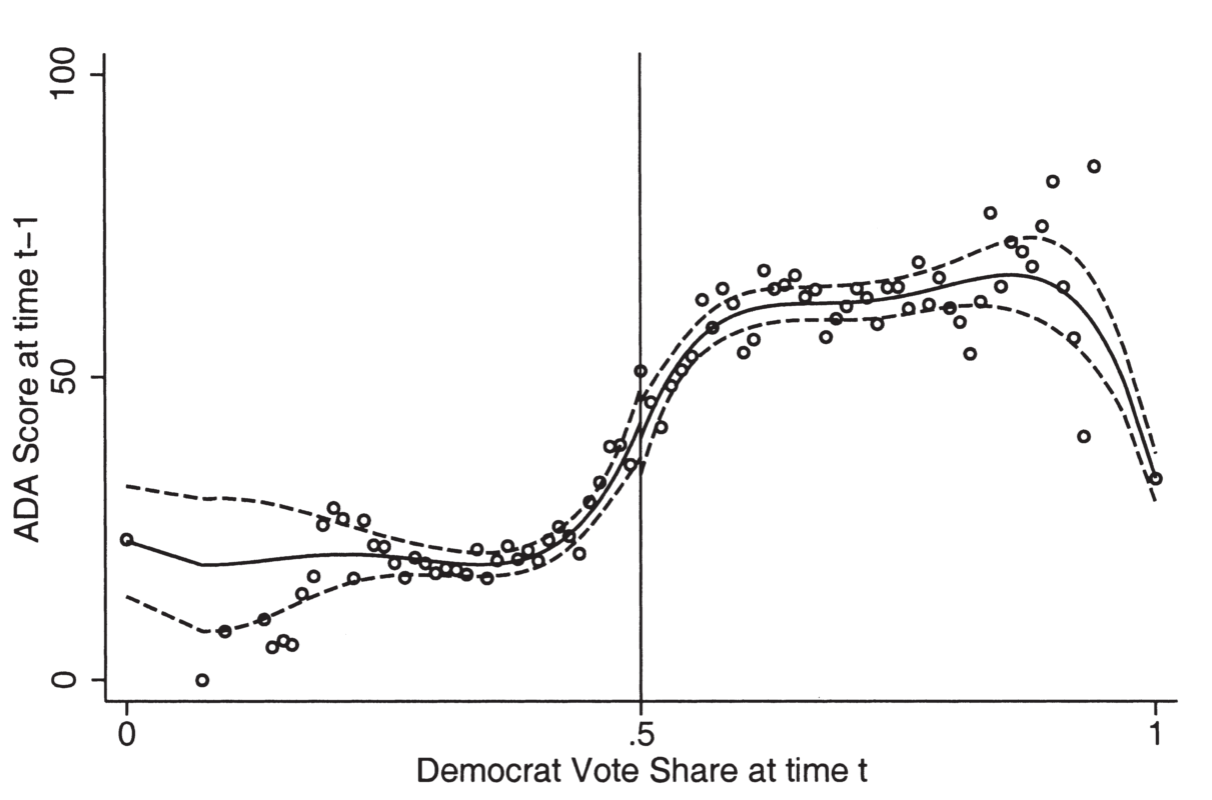

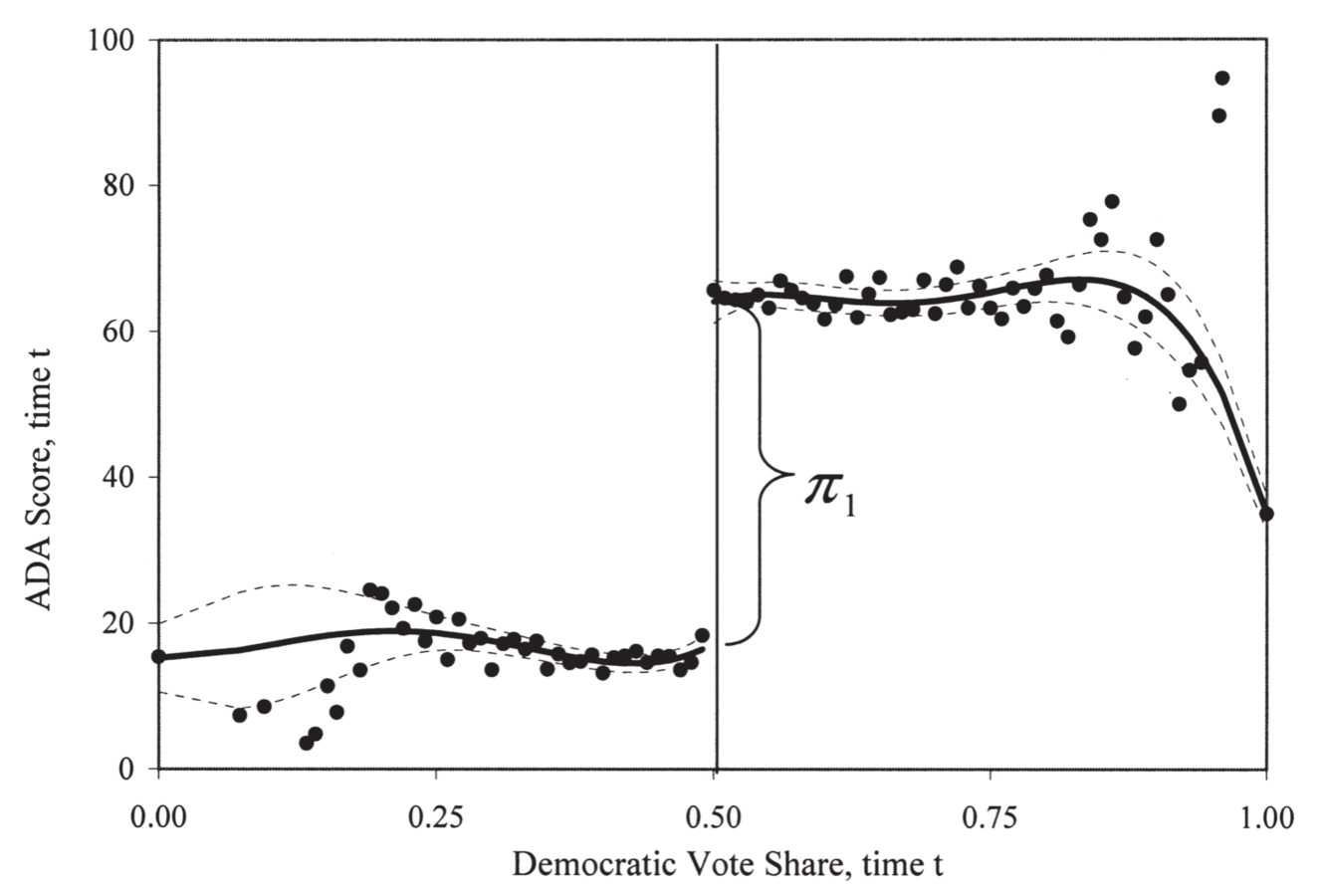

Outcome to look at:

Roll call votes

0

100

Liberal

Conservative

Quantify how liberal voting behaviour is (known as ADA Score)

Testing the no-commitment assumption (cont.)

Districts around 50% vote share are indeed similar

Source: Figure 5 of Lee et al. (2004)

But the winner's voting behaviour in Congress differs a lot

Source: Figure 2A of Lee et al. (2004)

Policy

Divergence

Summary

Available evidence suggests

politicians choose their ideal policy, not the median voter's

Citizen-candidate model helps understand such a world of politics

One candidate runs unopposed

Two party system (and its perpetual tendency)

Next lecture

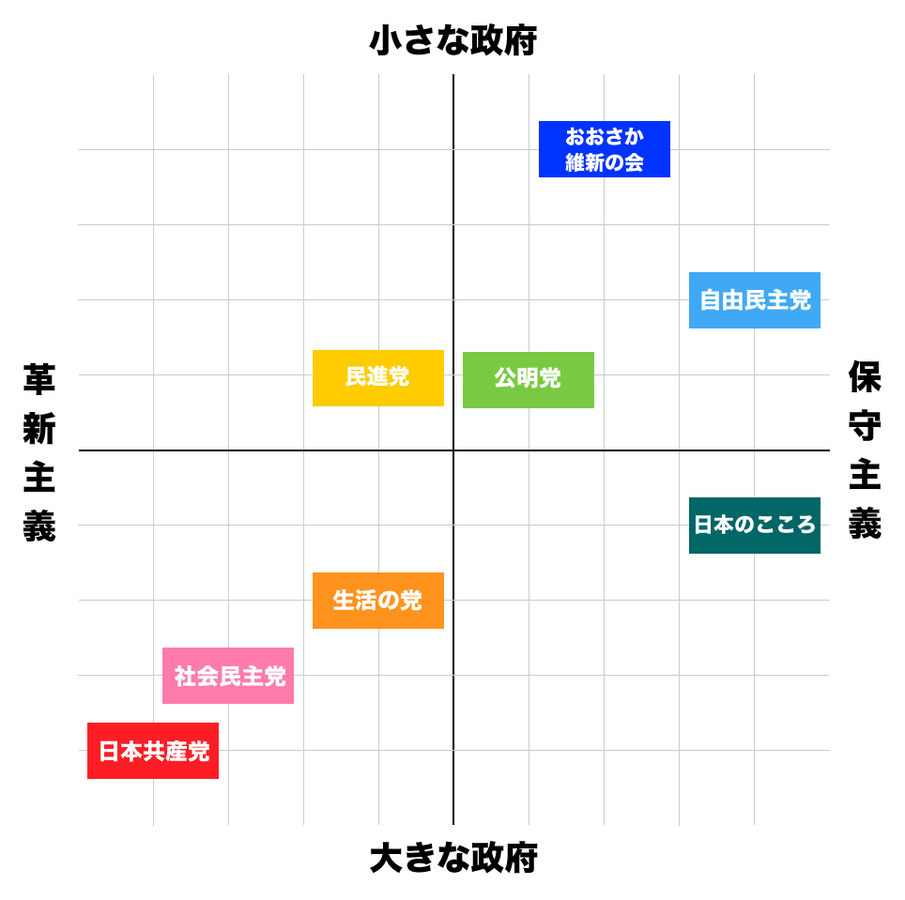

Who becomes a politician?

Next lecture

Why do politicians form

political parties?

Image source: nihonseiji.com/parties

This lecture is based on the following academic articles and books:

Besley, Timothy, and Stephen Coate. 1997. “An Economic Model of Representative Democracy.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 112(1): 85–114.

See also chapter 5 of Persson and Tabellini. 2000. Political Economics (MIT Press).

Lee, D. S., E. Moretti, and M. J. Butler. 2004. “Do Voters Affect or Elect Policies? Evidence from the U. S. House.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(3): 807–59.

Politics through the Lens of Economics: Lecture 4 Citizen-candidate Model

By Masayuki Kudamatsu

Politics through the Lens of Economics: Lecture 4 Citizen-candidate Model

- 4,380