Computational Biology

(BIOSC 1540)

Apr 8, 2025

Lecture 13A

Cheminformatics

Foundations

Announcements

- Today is our last quiz

Assignments

Quizzes

Final exam

OMETs

- I will drop your lowest assignment if the response rate is 80% or higher.

- Current response rate: 63%

After today, you should have a better understanding of

Quiz 04

Please put away all materials as we distribute the quiz

Fill out the cover page, and do not start yet

Sit with an empty seat between you and your neighbors for the quiz

Quiz ends around 9:55 am

When you are finished, please hold on to your quiz and feel free to doodle or write anything on the last page

After today, you should have a better understanding of

Ligand-based drug design

Structural insight into a disease is a privilege

Phenotypic drug screening involves testing compounds on an organism level to identify potential leads

Example: Drug screening on an antibiotic-resistant bacterial strain to identify potential new leads

LBDD uses known compounds to guide drug discovery

Ligand-based drug design (LBDD) relies on the properties of known bioactive compounds

LBDD does not require the structure of the target protein, making it useful when this is unknown

Assumption: Similar structures can lead to similar—hopefully improved—biological effects

Motivation: If we find compounds with little bioactivity, we can use LBDD to find compounds with similar chemical features to improve specific outcomes

Key differences between structure- and ligand-based drug design

Structure-Based Drug Design:

- Requires 3D structure of the target protein.

- Uses the binding site structure to model potential interactions.

- Often employs docking and molecular simulations.

Ligand-Based Drug Design:

- Requires no structural information of the target.

- Uses the chemical structure and activity of known ligands as guides.

- Relies on molecular similarity rather than direct binding predictions.

Chemical space exploration is still challenging, and now we need to identify similar compounds

After today, you should have a better understanding of

Molecular properties

Molecular properties are used to predict how a compound behaves in the body, before any biological testing

These properties help prioritize molecules for synthesis and testing by estimating solubility, permeability, bioavailability, and toxicity.

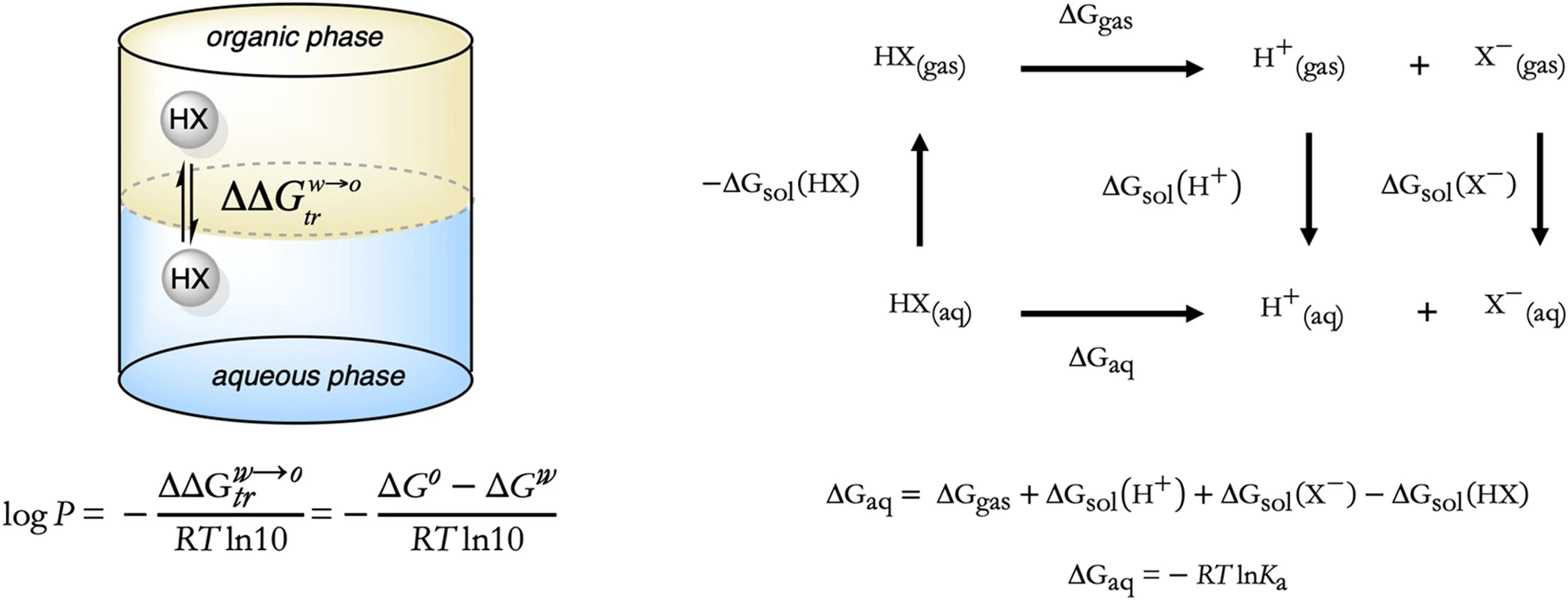

LogP quantifies lipophilicity, which affects absorption, distribution, and membrane permeability

LogP is the logarithm of a compound’s partition coefficient between octanol and water.

High LogP values indicate lipophilic (fat-loving) molecules that may permeate membranes more easily, but also may have poor solubility and toxicity risks.

Low LogP values mean hydrophilicity (water-loving), which helps with solubility but may hinder permeability.

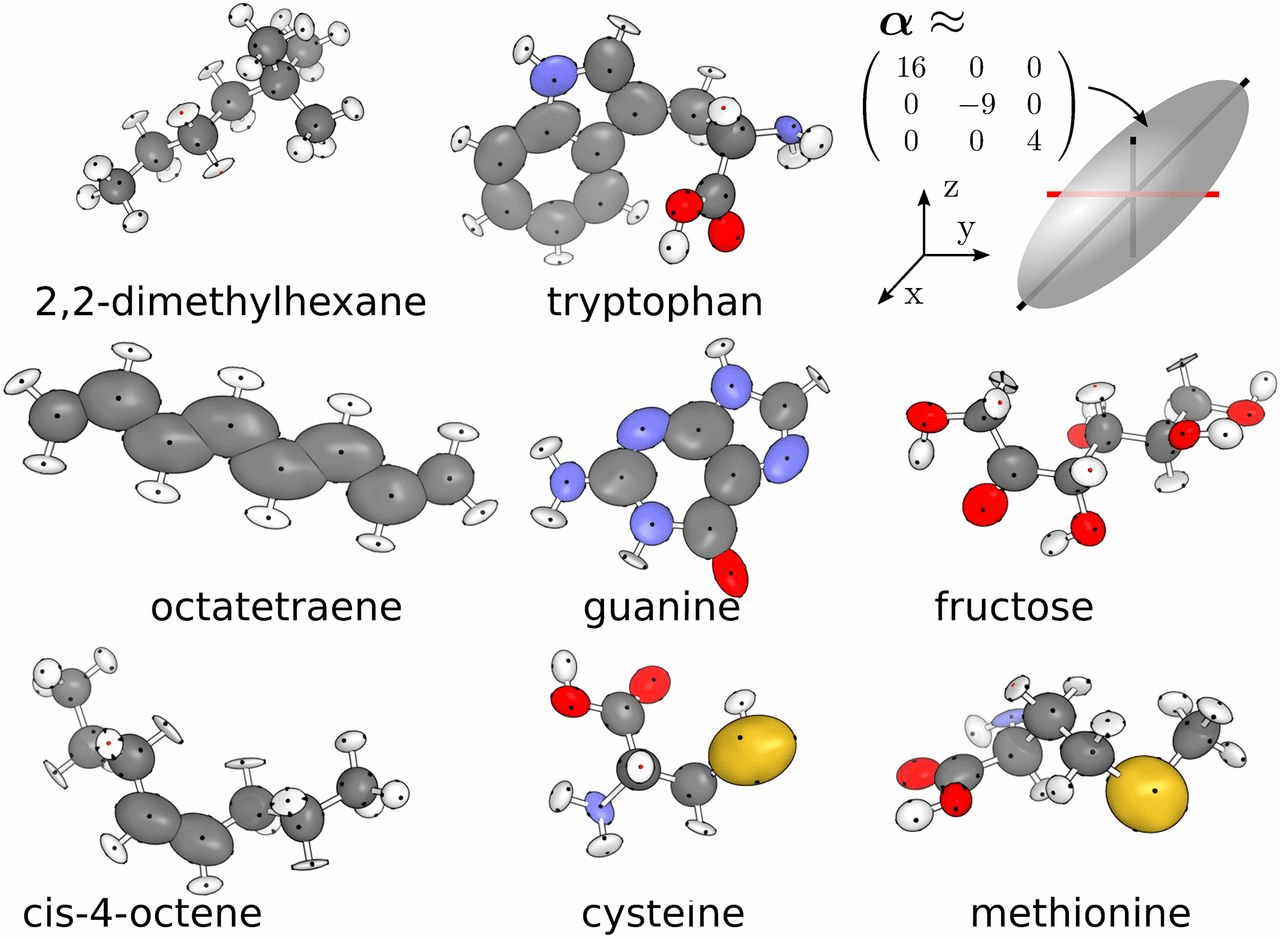

Molar refractivity (MR) measures polarizability and molecular volume

It is also used as a proxy for molecular volume—important in steric compatibility with binding pockets.

MR depends on molecular size and the type of atoms present.

Higher MR suggests greater polarizability, which can enhance binding via dispersion forces.

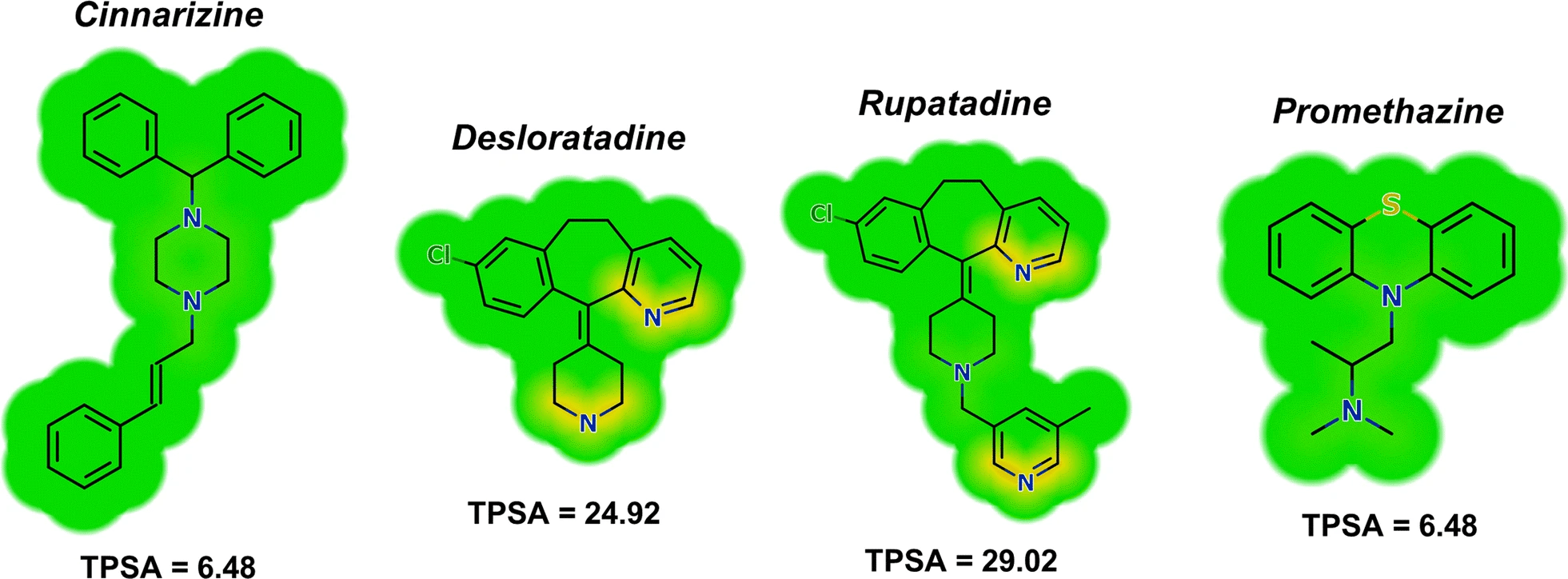

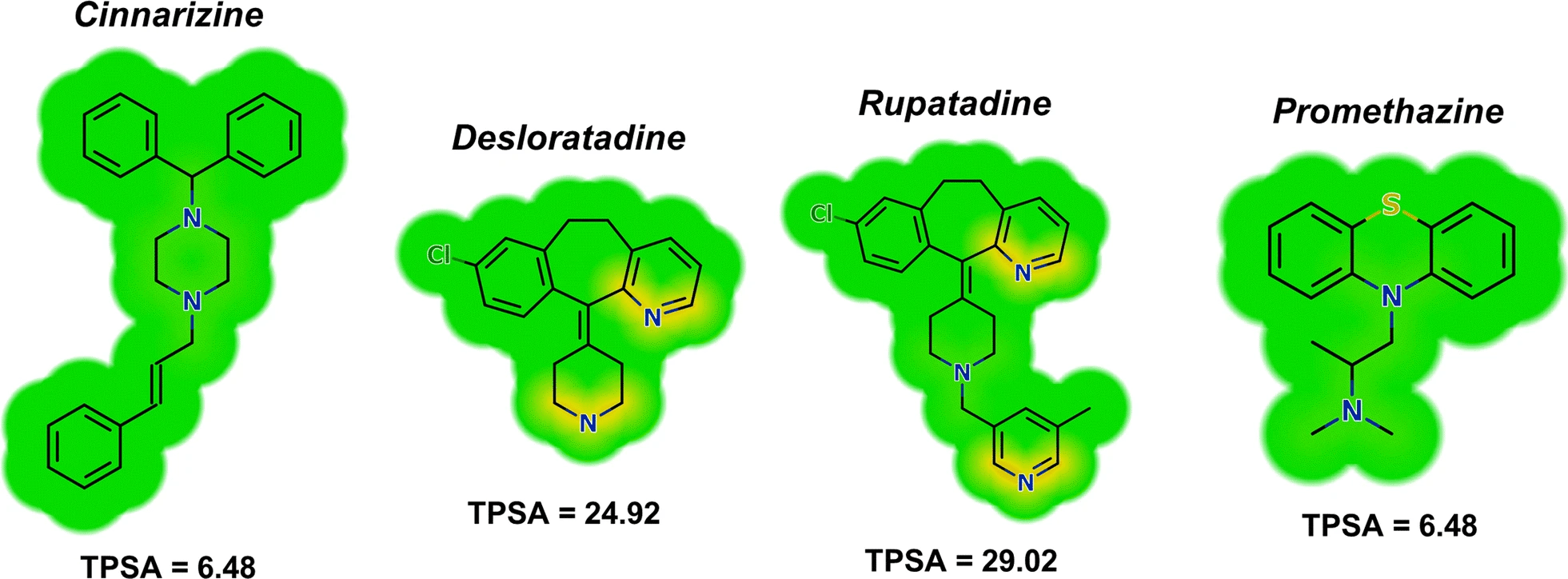

Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) predicts membrane permeability

Lower TPSA values (<90 Ų) suggest good potential for crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB).

It is calculated from the surface area of oxygen and nitrogen atoms (and their attached hydrogens).

Molecules with TPSA >140 Ų typically show poor oral bioavailability.

Rotatable bonds contribute to molecular flexibility

Drug-like molecules often have fewer than 10 rotatable bonds.

Fewer rotatable bonds generally mean better oral bioavailability and metabolic stability.

Highly flexible molecules may pay a greater entropic cost upon binding, reducing affinity.

While molecular properties provide crucial insight, they do not fully describe a molecule’s structure or function

Two compounds can have similar LogP, TPSA, and molecular weights—but behave very differently due to subtle structural variations (e.g., isomers or stereochemistry).

Properties are global summaries, but molecular similarity often depends on local structural features like functional groups, ring systems, or atom connectivity.

After today, you should have a better understanding of

Molecular similarity

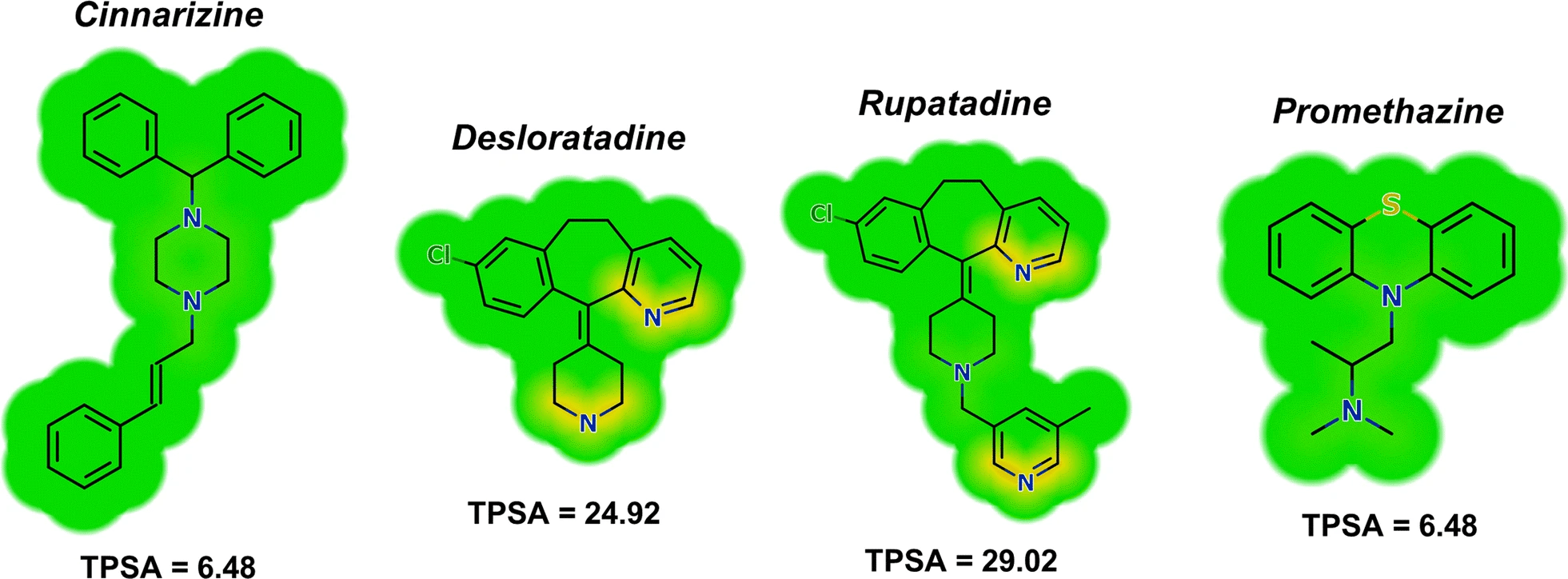

Quantifying molecular similarity is challenging

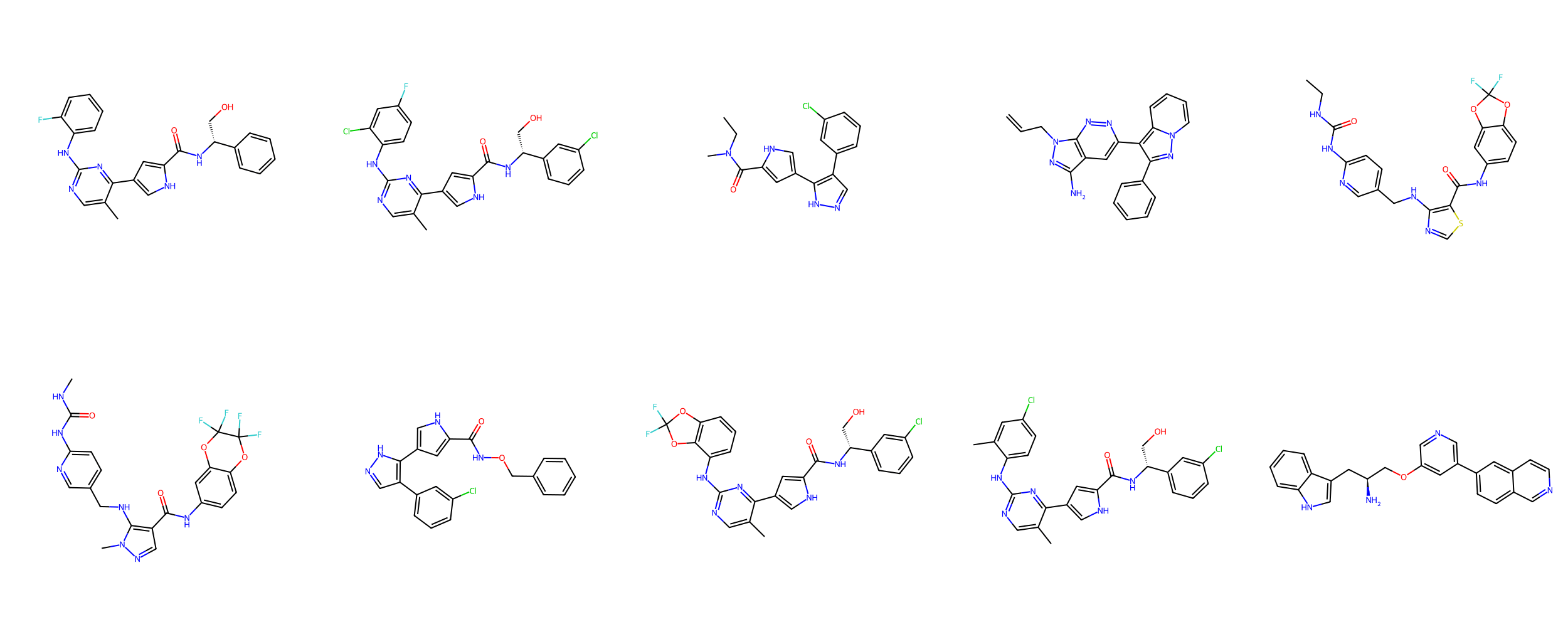

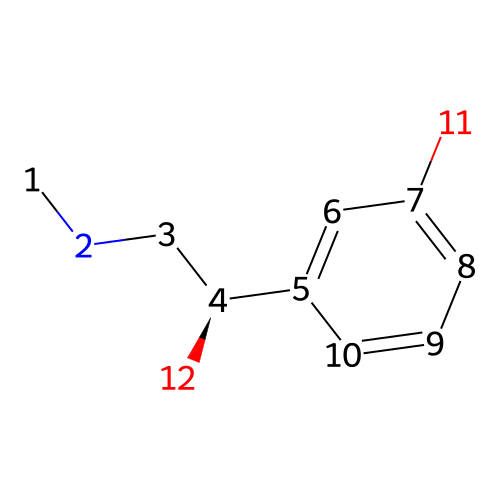

Which group of molecules should we pursue for increased bioafinity?

With your neighbors, determine how you would choose the group of molecules to pursue.

Suppose we performed an experimental high-throughput screen and identified these

potential leads

Group A

Group B

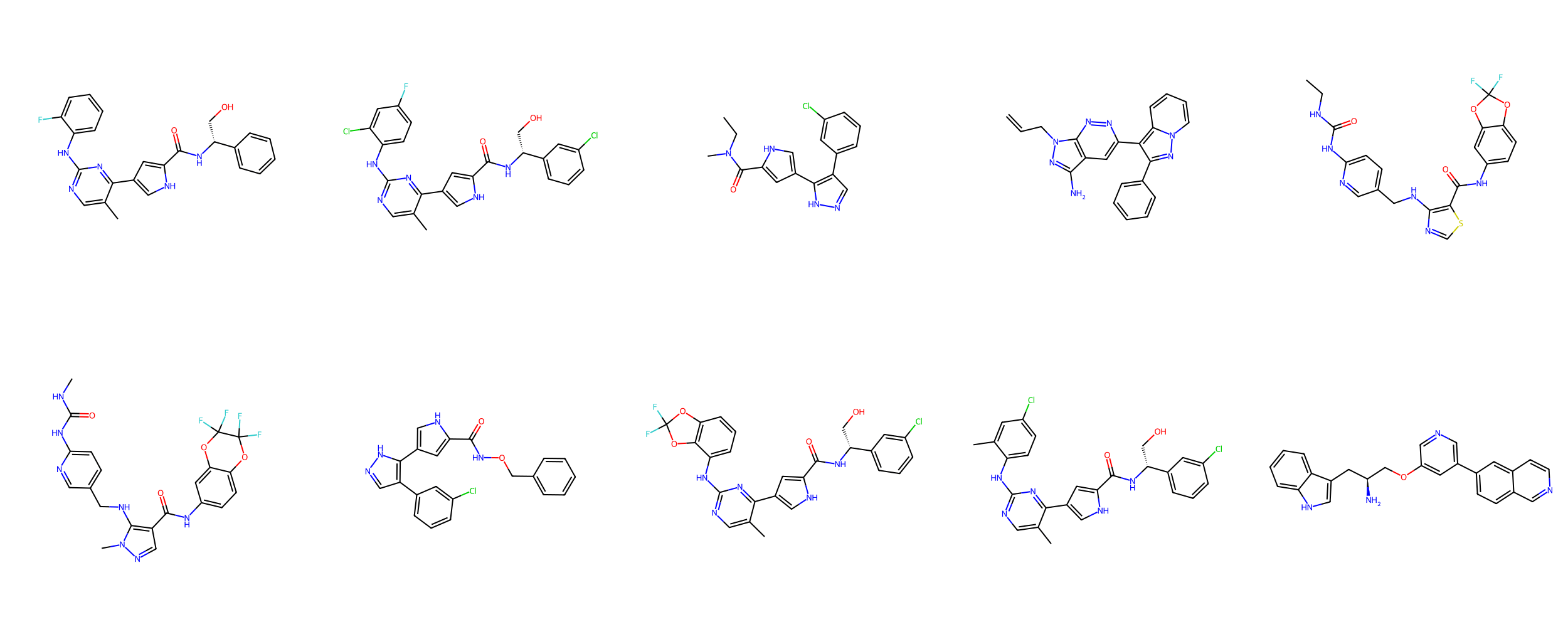

Molecular descriptors numerically encode chemical properties

Computed with SwissADME

Molecular weight

565.09 g/mol

475.97 g/mol

Indicates the overall size of the molecule, impacting drug distribution and elimination rates in the body.

LogP

4.08

4.30

Measures lipophilicity, which influences a molecule's ability to cross cell membranes and affects absorption and bioavailability.

Molar Refractivity

156.23

134.72

Relates to polarizability and electron cloud distribution, affecting intermolecular interactions and binding affinity.

TPSA

122.76 Ų

102.93 Ų

Estimates the molecule’s ability to form hydrogen bonds, impacting solubility and permeability across biological membranes.

Num. rotatable bonds

10

8

Reflects molecular flexibility, which can influence binding affinity and oral bioavailability.

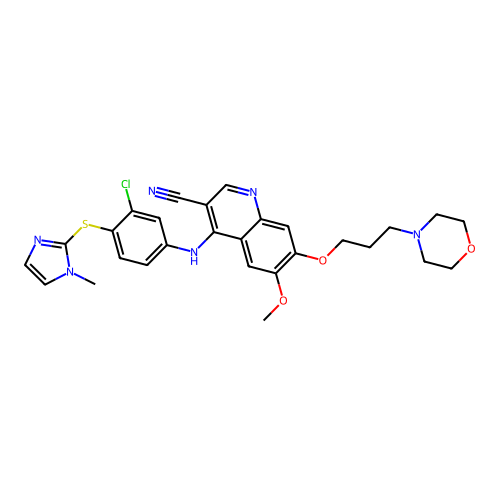

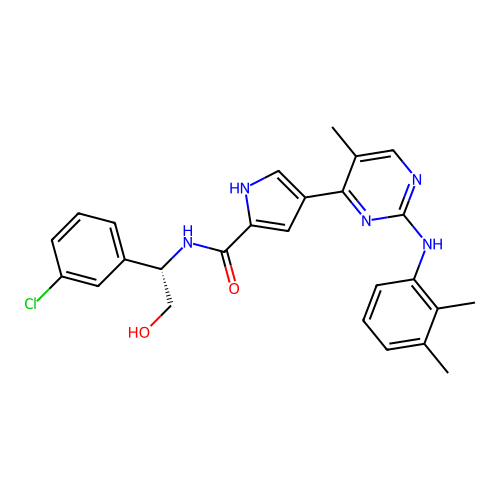

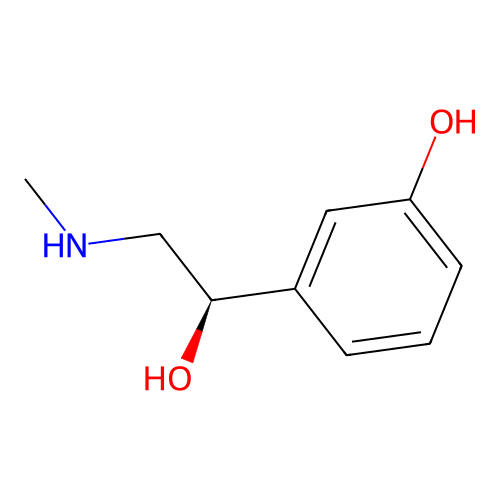

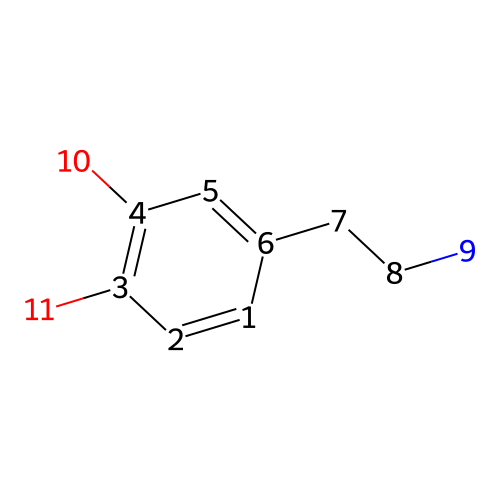

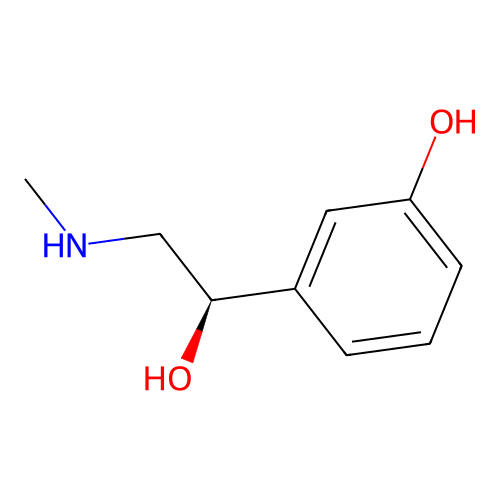

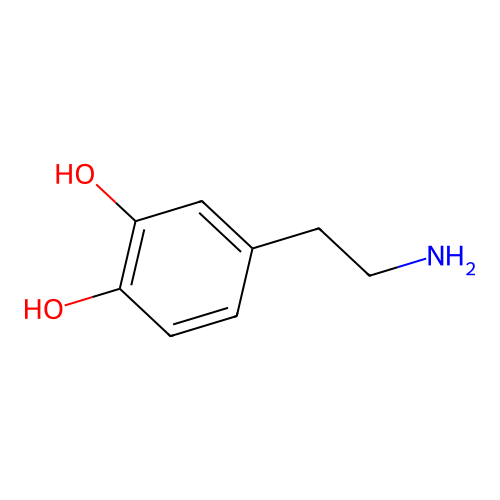

Molecules can have similar properties, with slight structural differences causing widely different functions

Computed with SwissADME

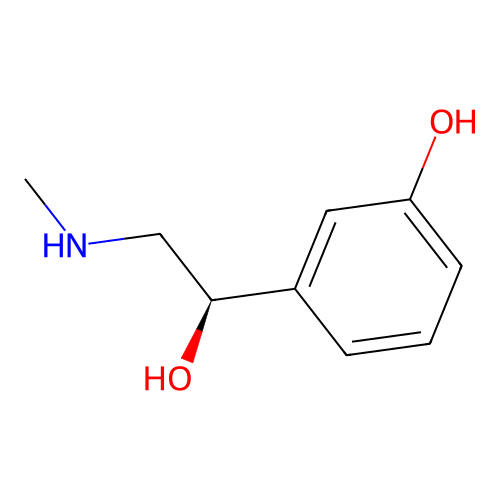

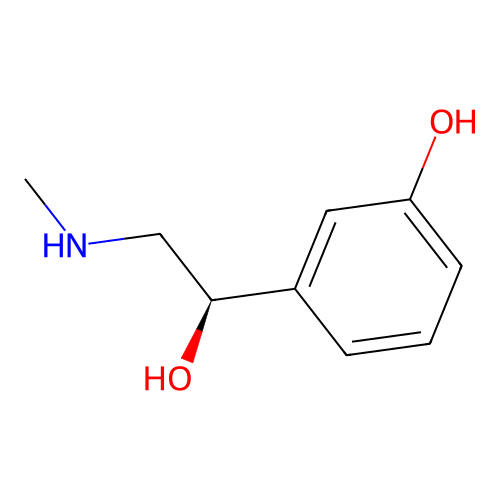

is a synthetic compound that acts as a vasoconstrictor by stimulating alpha-adrenergic receptors

Phenylephrine

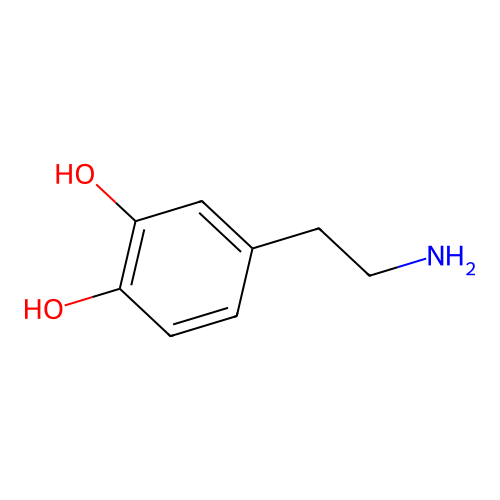

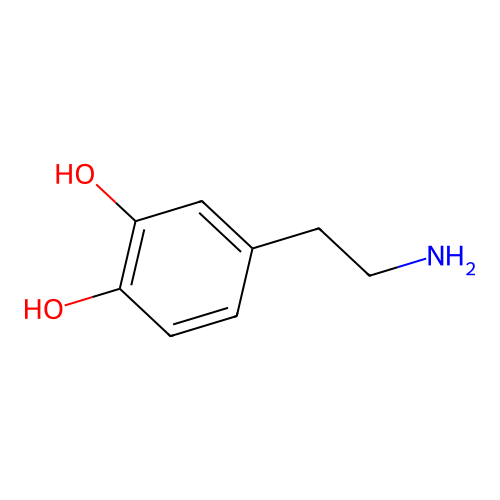

is a naturally occurring neurotransmitter in the brain and interacts with dopamine receptors

Dopamine

Simple descriptor comparisons are not sufficient for computing molecular similarity

Phenylephrine

Dopamine

Molecular weight

LogP

Molar Refractivity

TPSA

Num. rotatable bonds

Molecular weight

LogP

Molar Refractivity

TPSA

SMILES

167.21 g/mol

0.65

47.01

52.49 Ų

3

CNC[C@@H](C1=CC(=CC=C1)O)O153.18 g/mol

0.46

42.97

66.48 Ų

2

C1=CC(=C(C=C1CCN)O)OMolecular fingerprints encode structural information

Phenylephrine

Dopamine

Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) encode structural features into numerical representations

10011000000000000001000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000010000010000000000000000000010000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000100000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001000000000000000000000000000000000000000100000000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000010000000000001000000000000000000010000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001000000000000100100000000000000000000000000001000000001000000100000000000000000000000000000001000000000000000010000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000010000000000000000010010010000001001100000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000010000000000000000000000000000000000000001000000010000001000000000000000000000000001000000000000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000010000000000000000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001000100000000010010100000000000000000000000000000000010000000000000000000000000000000000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001000000000000000001001000000000from rdkit import Chem

from rdkit.Chem import rdFingerprintGenerator

fmgen = rdFingerprintGenerator.GetMorganGenerator(

radius=3, fpSize=1024,

atomInvariantsGenerator=rdFingerprintGenerator.GetMorganFeatureAtomInvGen()

)

mol = Chem.MolFromSmiles("C1=CC(=C(C=C1CCN)O)O")

print(fmgen.GetFingerprint(mol))How do we compute this?

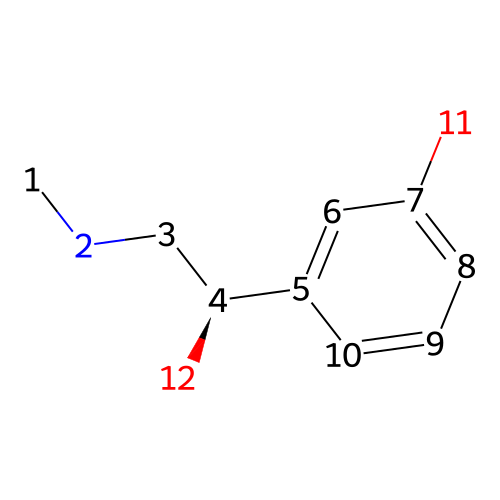

Hash functions are used to encode chemical information

For each heavy atom (i.e., not H), hash atom-specific properties

id10_iter0 = hash((6, 3, 0, 1))

print(id10_iter0) # 7468469475583712974

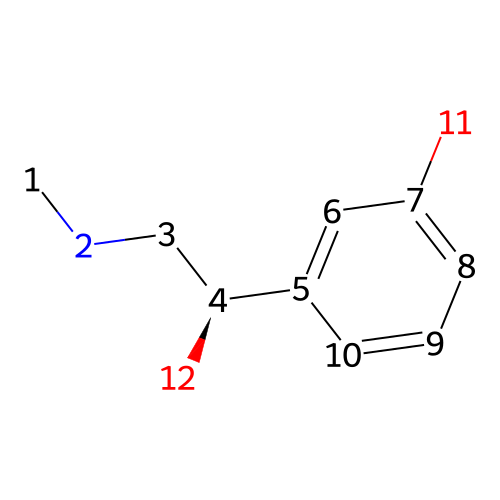

Let's look at carbons 6 and 10

Because of the same element and connectivity, they have the same ID0

id6_iter0 = hash((6, 3, 0, 1))

print(id6_iter0) # 7468469475583712974

Iteration 0 identifier

Atomic number

Valence

Formal charge

Ring membership

"Encoding" is a computational term for transforming information in a numerical format for computers

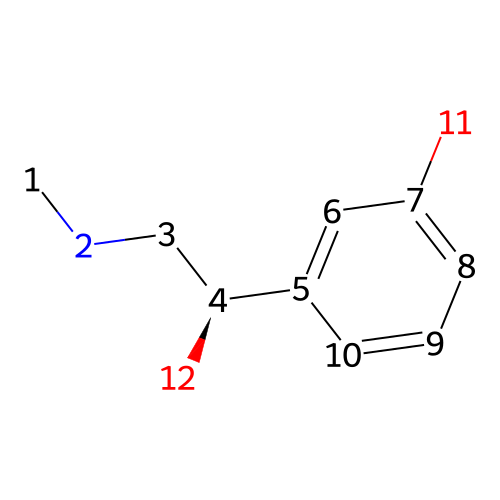

For each additional iteration of n, incorporate the hashes of connected atoms that are n bonds away

Each iteration encodes local chemical information into each atom's ID

We can repeat the process for larger n, which captures more chemical information at a (small) computational cost

Repeat for all atoms while hashing n - 1 IDs

Next, encode the atom IDs that are exactly one bond away

id6_iter1 = hash((

1, 7468469475583712974, # ID for atom 6

2, 901285887933171736, # ID for atom 5

1, 901285887933171736 # ID for atom 7

))

print(id6_iter1) # -1070477880882296059

Format:

(IterationNumber, AtomID, BondOrder1, AtomID1, BondOrder2, AtomID2, ...)

id10_iter1 = hash((

1, 7468469475583712974, # ID for atom 10

1, 901285887933171736, # ID for atom 5

2, 7468469475583712974 # ID for atom 9

))

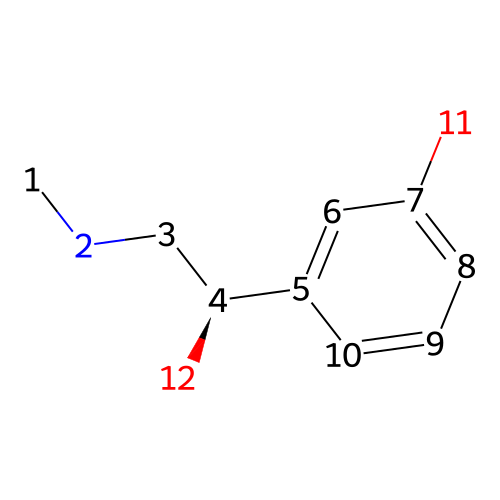

print(id10_iter1) # 9113858623660175530We keep track of atom IDs at each iteration to encode multiple "levels" of chemical information

# Iteration 0

[-96873481, -5237400, -608624, -40896092, 13106358, 39304191, 13106358, 39304191, 39304191, 39304191, 18495798, 18495798]

# Iteration 1

[-12887828, 34836456, -82428984, -76182021, 57441373, 18535308, 36698099, -16062189, -71082609, -16062189, -13803757, -35226747]

# Iteration 2

[-30242937, -22342045, -3701095, -83323106, -81401022, -79585126, 259777, -18164777, -83853893, -9624634, -63890015, -86218719]

# Iteration 3

[24482285, -67056973, -1049934, 58183281, 9686245, 65319696, -89546467, 90525418, -96278682, -31838946, -41820336, -42202112]# Iteration 0

[39304191, 39304191, 13106358, 13106358, 39304191, 13106358, -608624, -608624, -2248911, 18495798, 18495798]

# Iteration 1

[-16062189, -16062189, -54942758, -54942758, 18535308, 80518135, -46276084, 85303560, -4225841, -13803757, -13803757]

# Iteration 2

[45202524, -32527659, 91315393, -86313403, 74663225, 43056615, -92441264, 61456743, 35268850, -86729888, -86729888]

# Iteration 3

[17051553, -83857497, -10864101, 42020134, 84228020, 88509243, 53634925, 58427327, 85169475, -62345869, -23012595]Similar structural features will share atom IDs

until our iteration starts incorporating different structural features

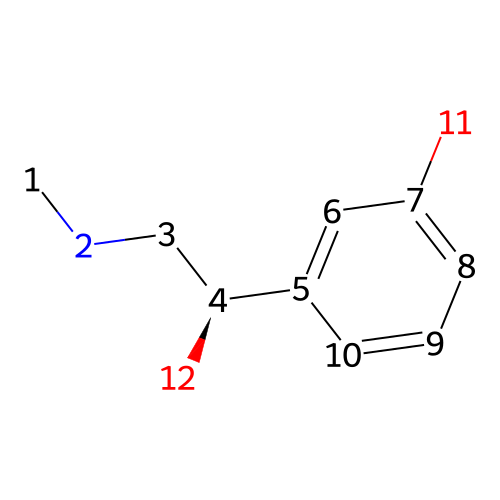

Atom IDs are encoded into a bit array

We can get a collection of atom IDs, but how would we rapidly compare molecules with different number of atoms?

We use bit arrays, which are fixed-length collections of ones and zeros

10101100 10101100

AND 11011010

--------

10001000

11011010This allows efficient operations

10101100

OR 11011010

--------

11111110Features that are in both molecules

Features that are in either molecules

Converting atom IDs to bit arrays

ecfp = [0, 0, 0, 0, ..., 0, 0, 0]-1070477880882296059 % 1024 = 908Decide on length of bit array, for example, 1024 and fill with zeros

Divide each atom ID by the length of the array and determine the remainder

Set the value of the bit array at that index to 1

ecfp[908] = 1

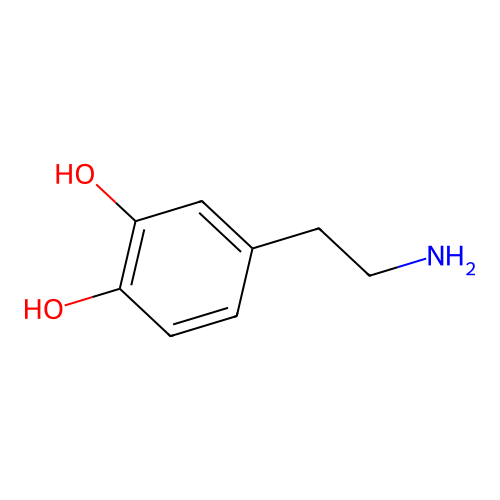

10011000000000000001000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000010000010000000000000000000010000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000100000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001000000000000000000000000000000000000000100000000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000010000000000001000000000000000000010000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001000000000000100100000000000000000000000000001000000001000000100000000000000000000000000000001000000000000000010000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000010000000000000000010010010000001001100000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000010000000000000000000000000000000000000001000000010000001000000000000000000000000001000000000000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000010000000000000000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001000100000000010010100000000000000000000000000000000010000000000000000000000000000000000000000000100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001000000000000000001001000000000Tanimoto similarity compares the ECFPs between two molecules

Using bit operations, we can compute similarity using Tanimoto

- a is the number of bits set to 1 in vector A.

- bbb is the number of bits set to 1 in vector B.

- ccc is the number of bits set to 1 in both vectors A and B (the intersection).

This formula measures the ratio of the shared features to the total number of unique features between two molecules.

a = len(fp1_bits)

b = len(fp2_bits)

c = len(fp1_bits & fp2_bits)Molecular similarity: The concept that similar molecules often show similar biological effects.

Tanimoto similarity ranges

Phenylephrine

Dopamine

How similar does ECFPs and Tanimoto say these molecules are?

After today, you should have a better understanding of

Quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR)

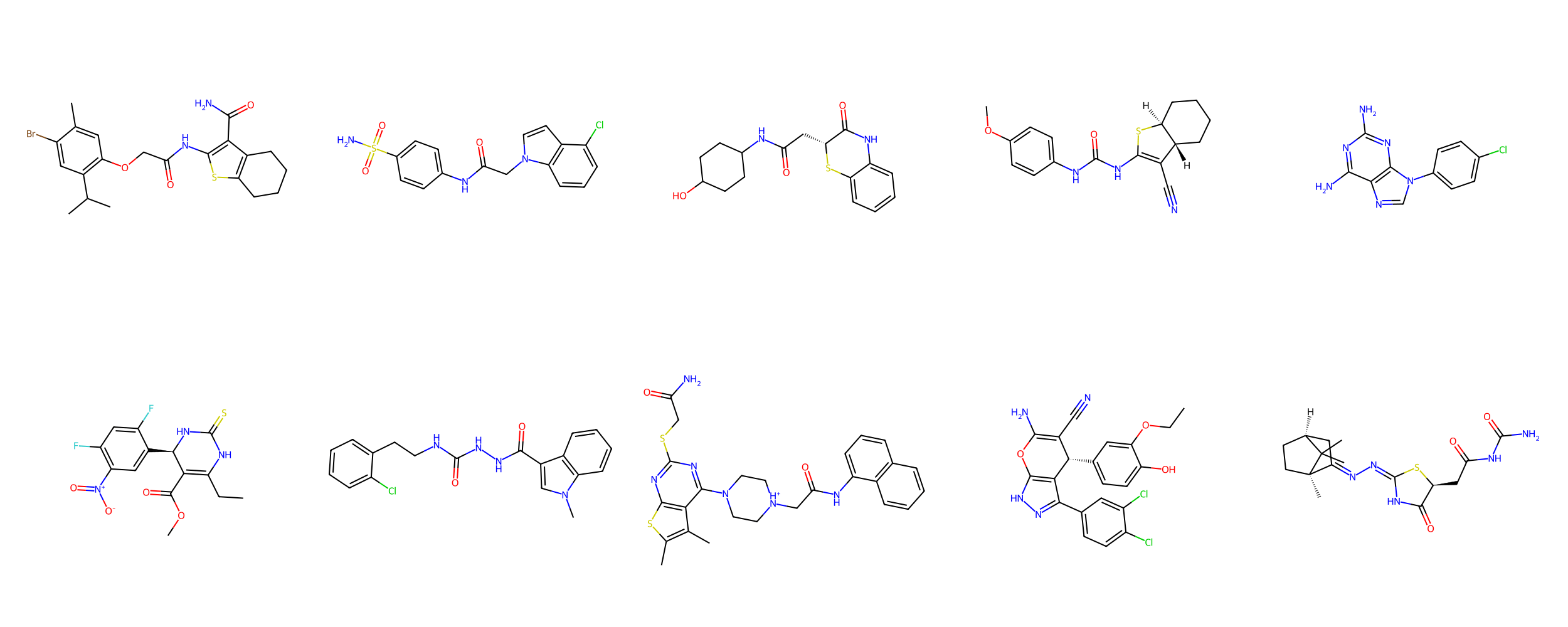

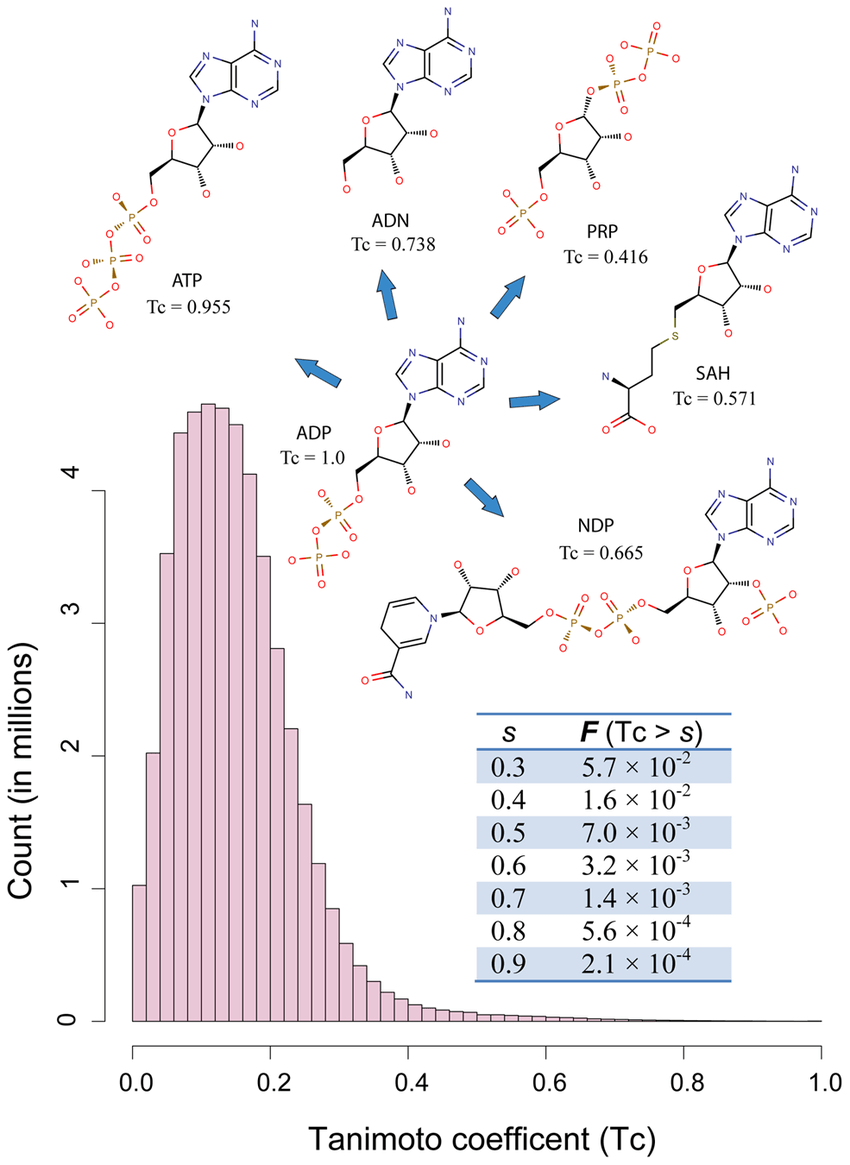

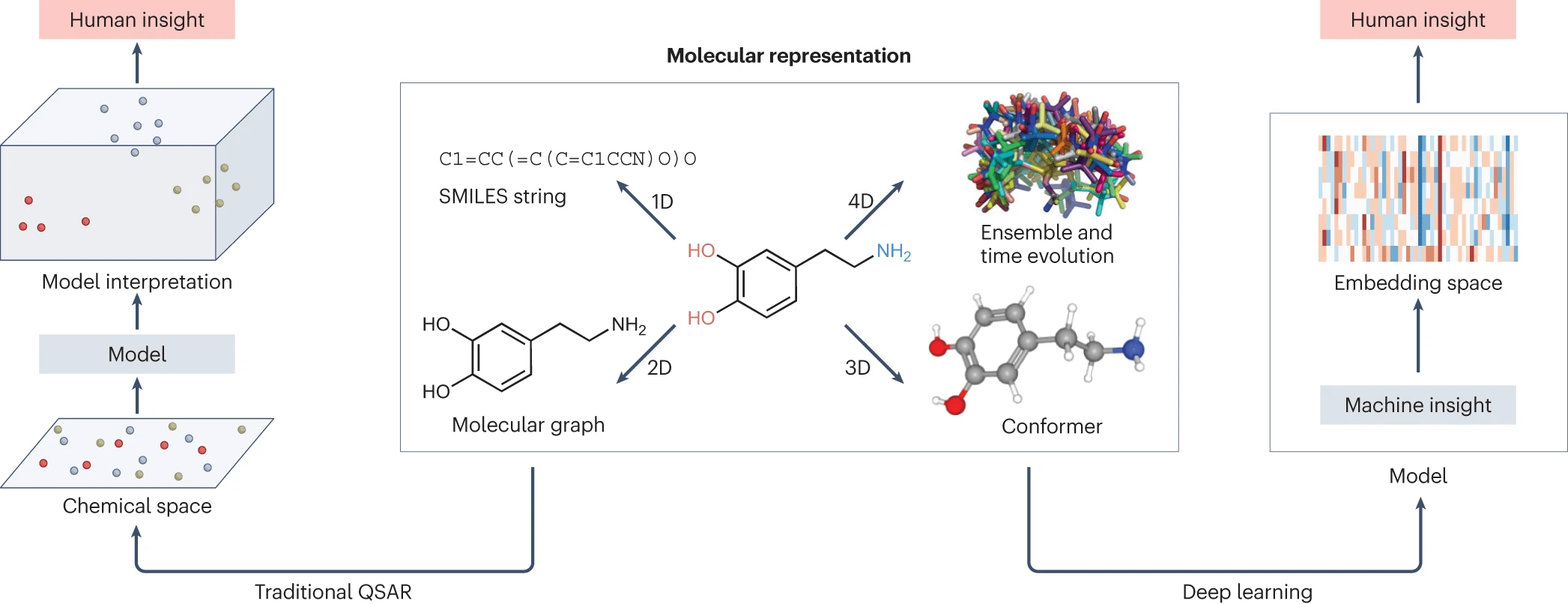

QSAR models link chemical structure with biological activity

Purpose: To predict the biological activity of molecules based on their structure.

Motivation:

- Reduces the need for experimental screening.

- Helps identify potential drugs quickly and cost-effectively.

Example: Predicting if a compound is likely to be an inhibitor of a target enzyme based on known inhibitors.

Types of QSAR Models:

- Linear Models: Simple, interpretable, e.g., linear regression.

- Nonlinear Models: Capture complex relationships, e.g., neural networks.

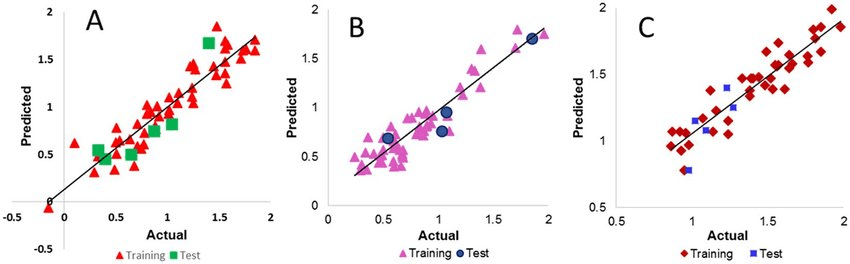

Developing a QSAR model follows systematic steps

- Data Collection: Gather biological activity and molecular data.

- Descriptor Calculation: Calculate numerical descriptors for each molecule.

- Model Selection and Training: Use machine learning to correlate descriptors with activity.

- Model Validation: Test model accuracy with independent datasets.

- Interpretation and Application: Use the model for predicting new molecules.

Linear regression models are simple but effective for QSAR analysis

Fits a linear relationship between descriptors and output

- Advantages: Easy to interpret.

- Limitations: Limited to linear relationships; struggles with complex datasets.

Nonlinear models capture complex relationships in QSAR data

Examples of Nonlinear Models:

- Neural Networks: Capture complex, nonlinear patterns in large datasets.

- Random Forests: Effective for high-dimensional data, robust against overfitting.

Example: Predicting toxicity, where relationships between descriptors and outcomes are often nonlinear.

After today, you should have a better understanding of

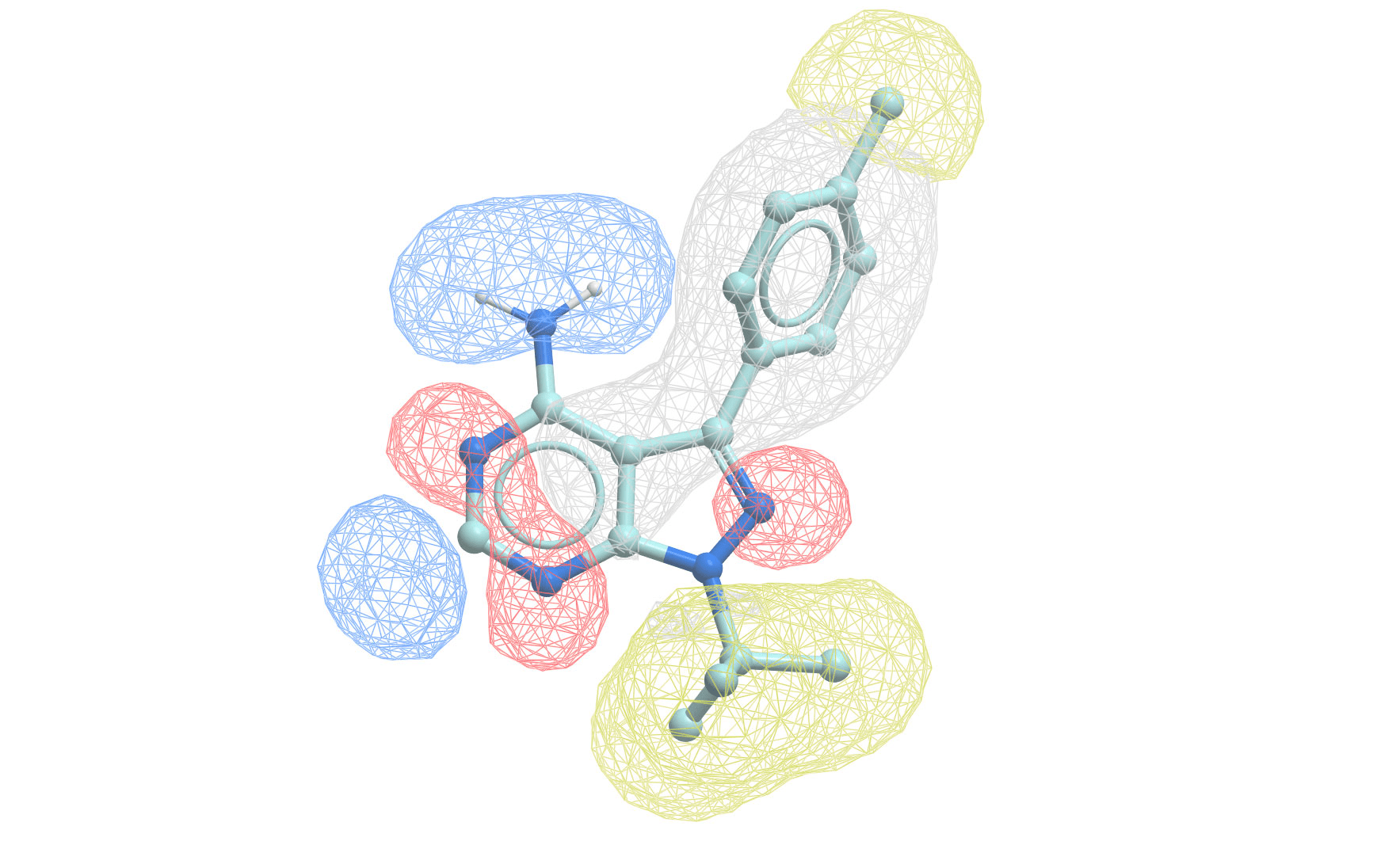

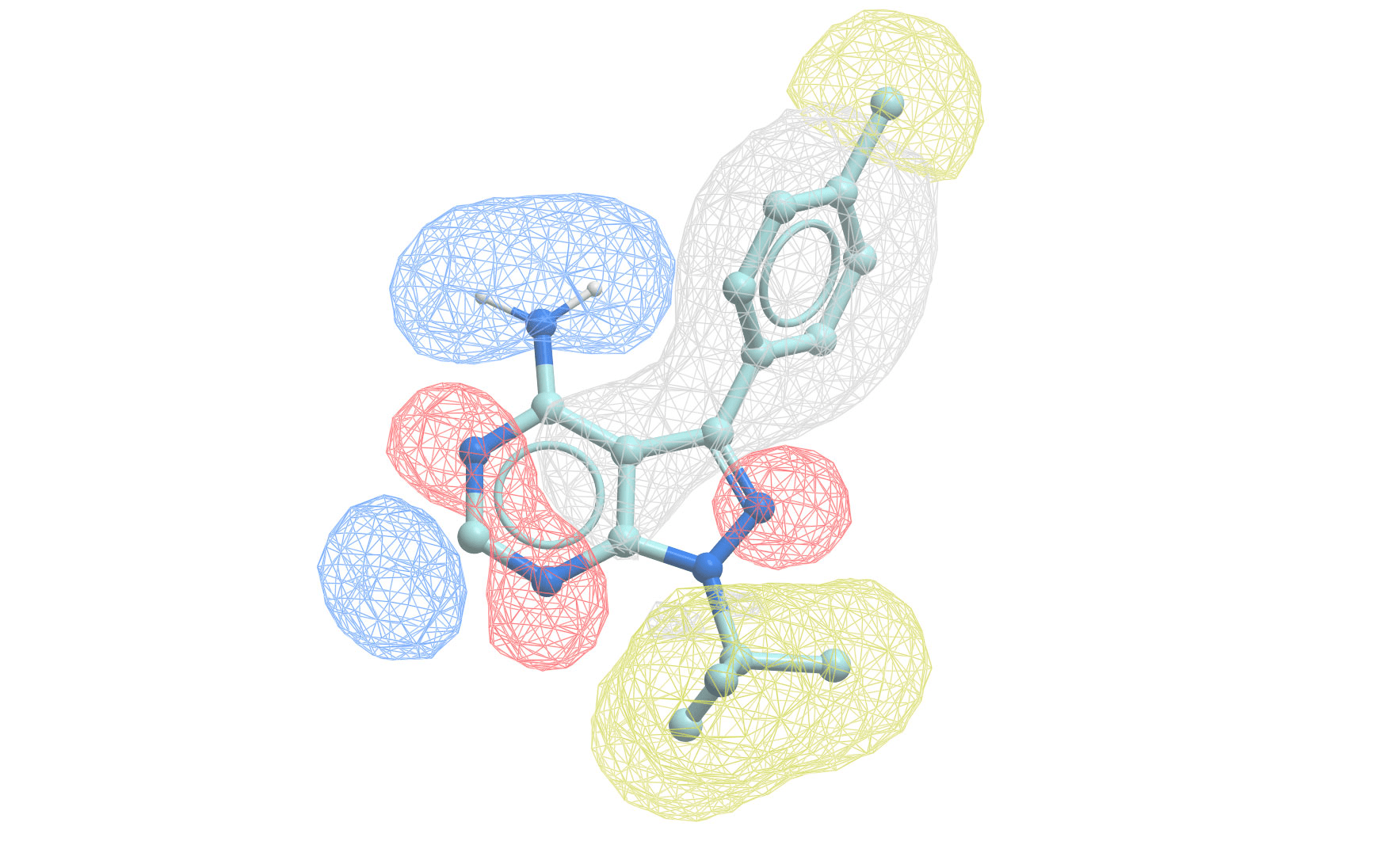

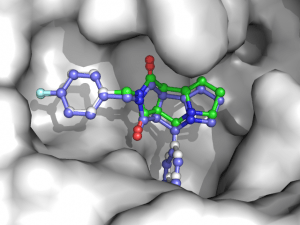

The role of pharmacophore modeling in identifying essential molecular features for activity.

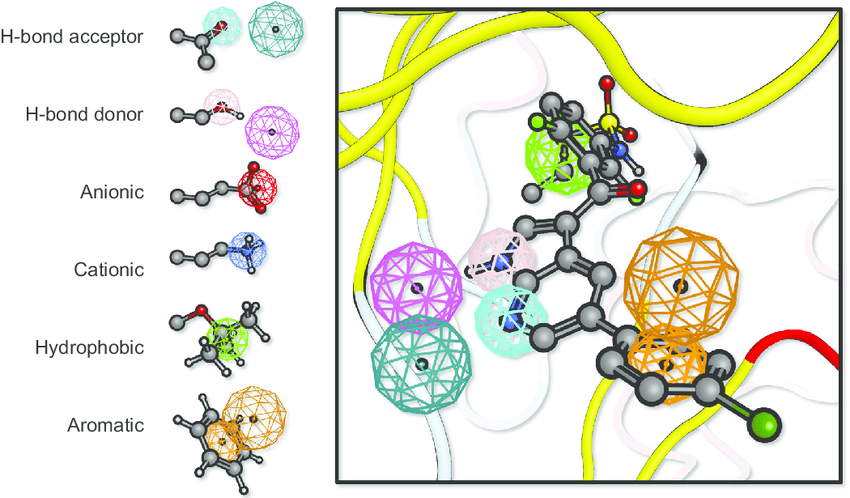

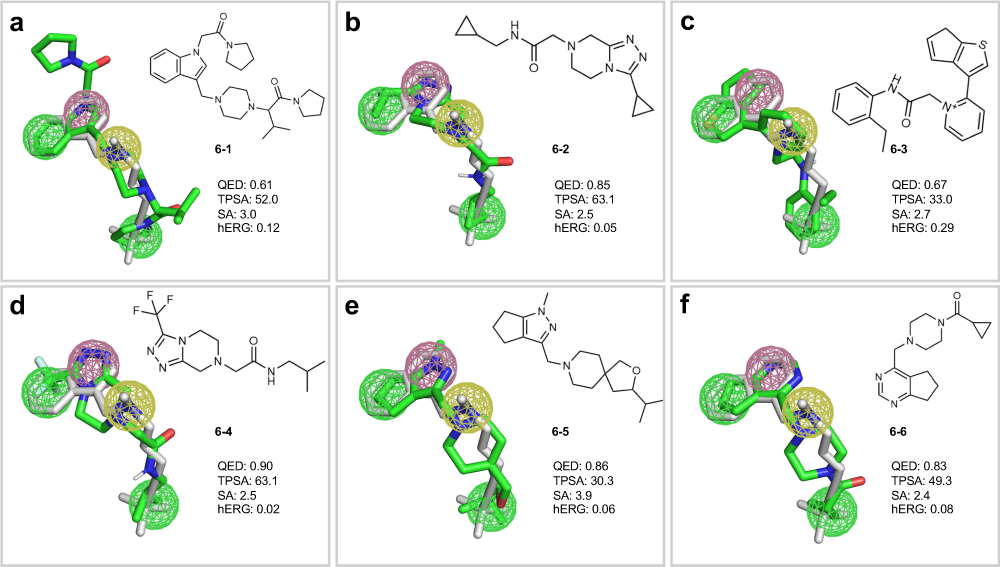

Where QSAR quantifies activity, pharmacophore modeling identifies critical molecular features for activity

Pharmacophore modeling defines the essential features needed for biological activity

A pharmacophore is the 3D arrangement of molecular features required for biological activity

Building a pharmacophore model requires multiple active compounds

Step 1: Align active molecules

- Identify common structural features

- Determine spatial relationships

- Consider multiple conformations

Step 2: Define feature locations

- Mark shared pharmacophoric points

- Establish distance constraints

- Set tolerance spheres

Before the next class, you should

Lecture 13B:

Cheminformatics -

Methodology

Lecture 13A:

Cheminformatics -

Foundations

Today

Thursday

BIOSC 1540: L13A (Cheminformatics)

By aalexmmaldonado

BIOSC 1540: L13A (Cheminformatics)

- 166