The Book

Amaranth Borsuk

University of Washington, Bothell

@amaranthborsuk

amaranthborsuk.com

Clay Bulla (Sumer, 3500 BCE) Clay Tablet (Mesopotamia, 2800) Scroll (Papyrus: 1900, Parchment: 1600) Jiance (China, 1600)

Sutra (India and Sri Lanka, 450) Khipu (Peru, 2500/1500) Waxed Tablet (Greece, 400) Parchment notebook (Rome, 55)

Concertina (China, 618 CE) Butterfly (960) Wrapped back (1127) Stab binding (1644)

Abbreviated timeline

- 2800 BCE – 100 CE — Clay tablet

- 2600 BCE – 700 CE — Papyrus Scroll

- 150 CE – present — Codex

- 600–1200 — Monastic illuminated manuscripts

- 1041 — Chinese movable type

- 1450 — Printing press, movable type, oil-based ink

- 1932 — Audiobook records for the visually impaired

- 1971 — Project Gutenberg Ebooks (Michael S. Hart)

- 1986 — Earliest e-readers (Franklin, NuvoMedia)

- 2007 — Kindle e-reader

Material metaphors

Literature was never only words, never merely immaterial verbal constructions. Literary texts, like us, have bodies, an actuality necessitating that their materialities and meanings are deeply interwoven into each other.

—N. Katherine Hayles

Writing Machines (2002)

Chansonnier de Jean de Montchenu (ca. 1470, coll. BNF), 2007 facsimile, image via UC Libraries.

Artists' Books

[An artist's book] integrates the formal means of its realization and production with its thematic or aesthetic issues. […] It has to have some conviction, some soul, some reason to be and to be a book in order to succeed.

—Johanna Drucker

The Century of Artists’ Books (2004)

Alison Knowles, The Big Book (1967).

Between Page & Screen

Mediated Reading

As much acts of interpretation as material things, as much processes as objects, media are not merely storage mechanisms somehow independent of the acts of reading they record.

—Craig Dworkin

No Medium (2013)

Tender Claws, Pry (2014).

the Reader

It might be any art: an artist’s book could be music, photography, graphics, intermedial literature. The experience of reading it, viewing it, framing it—that is what the artist stresses in making it.

—Dick Higgins

"A Preface" (1985)

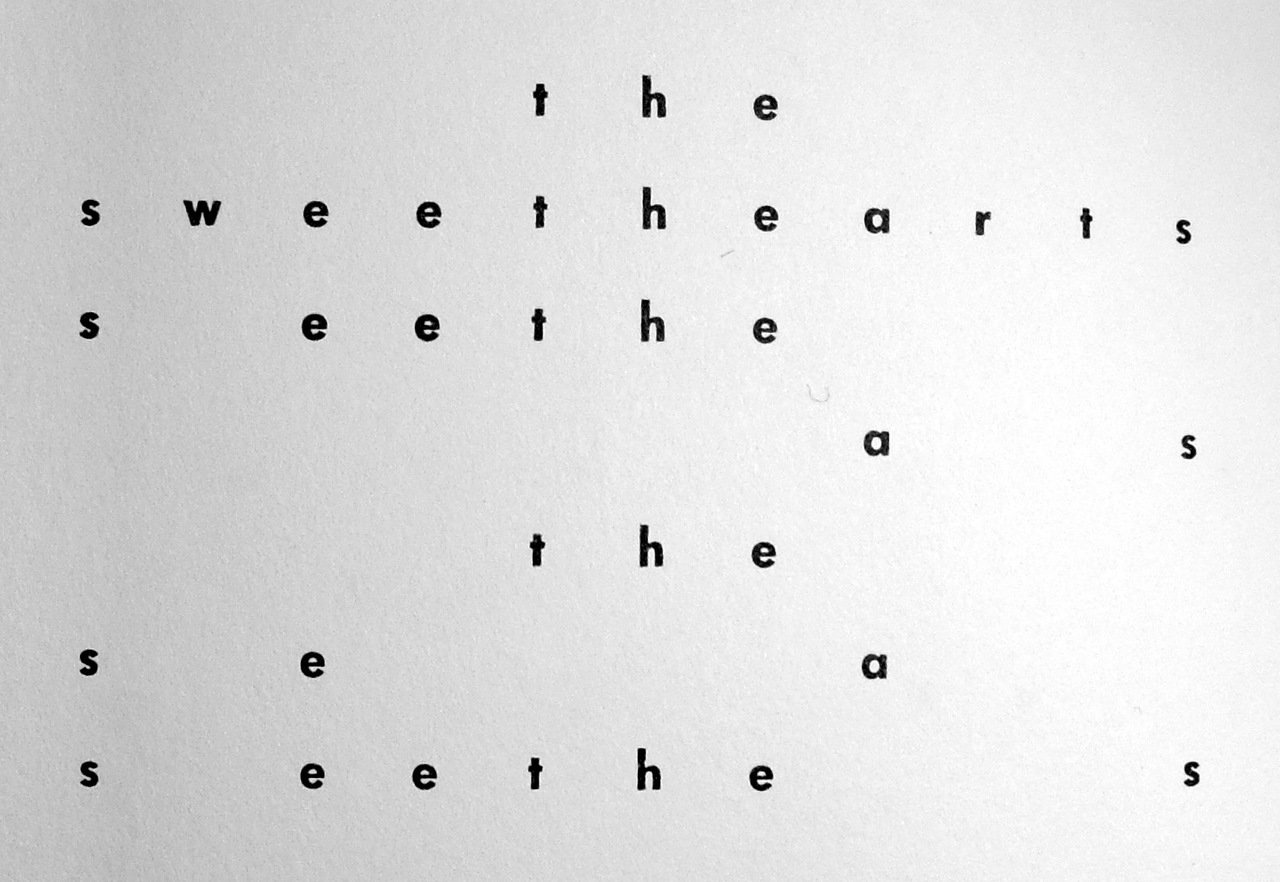

Emmett Williams, Sweethearts (1967).

Sweethearts, digital facsimile by Mindy Seu, sweetheartsweetheart.com

- The Book as Object

- The Book as Content

- The Book as Idea

- The Book as Interface

The book

The Book as VR

A book is a sequence of spaces.

Each of these spaces is perceived at a different moment - a book is also a sequence of moments.

. . . .

A book is not a case of words, nor a bag of words, nor a bearer of words.

—Ulises Carrión

“The New Art of Making Books” (1975)

Tunnel Under The Thames (S & J Fuller, London, 1826). Hand-colored peepshow. Collection of State Library of South Australia.

The Book as Cinematic Space

Michael Snow, Cover to Cover (1975).

The Book as Recombinant Structure

Regiomontanus, Calendrium (Venice: Maler, Ratdolt & Löslein, 1476).

| Raymond Queneau, Cent Mille milliards de poèmes (Gallimard, 1961).

The Book as ephemeral

Wait, later this will be nothing

—Dieter Roth

Snow (1964/65)

Dieter Roth, Literaturwurst (1969).

The Book as mute object

Alisa Banks, Edges: Cornrow (2007).

The book as interface

Books don’t simply mediate a meeting of minds between reader and author. They also broker (or buffer) relationships among the bodies of successive and simultaneous readers—or even between one person who holds the book and others before whose gaze, or over whose dead body, she turns its pages.

—Leah Price, How to Do Things with Books

in Victorian Britain

A House of Dust

a house of (material)

(location)

using (light source)

inhabited by (inhabitants)

ALISON KNOWLES & JAMES TENNEY

(COLOGNE: GBR KONIG VERLAG, 1968)

A book of dust

Based on Nick Montfort's reimplementation

of Alison Knowles and James Tenney's House of Dust,

a 1967 computer-generated poem in Fortran, using Javascript.

The Book

By Amaranth Borsuk

The Book

Brown Bag talk, MIT Press, September 2017

- 1,663