k-means, LASSO, and Random Forest

Applications for Machine Learning Working Group from

The Mortality and Medical Costs of Air Pollution: Evidence from Changes in Wind Direction

paper Summary

- Measure the impact of fine particulate matter pollution (PM 2.5) on mortality and healthcare use

- IV approach that leverages local wind changes on (non-local) pollution

- Use machine learning to simulate life-years lost (LYL) due to pollution exposure

- K-means for data cleaning

- Hazard rate refinement using high-dimensional datasets

- LASSO

- Random Forest

- Chernozhukov et al. (2018) ML for heterogeneity (I won't cover, highly technical that would probably need its own session)

Empirical strategy

- How to estimate how long someone has to live?

- Cox proportional hazards model

Empirical strategy

- How to estimate how long someone has to live?

- Cox proportional hazards model:

Baseline survival rate

Individual characteristics

Empirical strategy

- How to estimate how long someone has to live?

- Cox proportional hazards model:

Baseline survival rate

Individual characteristics

>1: increased risk

<1: decreased risk

Empirical strategy

- How to estimate how long someone has to live?

- Cox proportional hazards model:

Baseline survival rate

Individual characteristics

Estimate with log partial likelihood

Empirical strategy

- How to estimate how long someone has to live?

- Cox proportional hazards model:

Estimate with log partial likelihood

Empirical strategy

- How to estimate how long someone has to live?

- Cox proportional hazards model:

Observe death =1

The risk set: the entire set of subjects at risk at time i

Characteristics of those individuals

Empirical strategy

- How to estimate how long someone has to live?

- Cox proportional hazards model:

Maximize this, or rather, minimize the negative of this

Intuitively, choose β such that it weights riskier characteristics more

Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proportional_hazards_model and http://www.sthda.com/english/wiki/cox-proportional-hazards-model

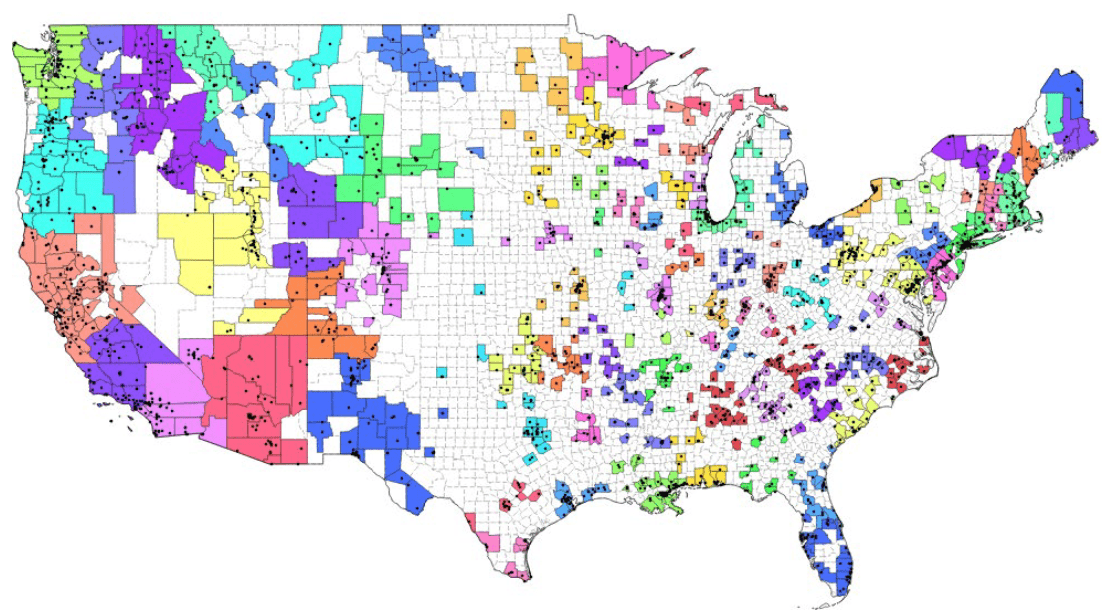

Problem:

- There are nearly 1,400 PM 2.5 monitors in the country, but they are sparsely placed.

- Locally produced pollution will generate data noise based on proximity to certain monitors.

- Local pollution unlikely to reach all individuals in a given area.

Measurement Error!

Problem:

- There are nearly 1,400 PM 2.5 monitors in the country, but they are sparsely placed.

- Locally produced pollution will generate data noise based on proximity to certain monitors.

- Local pollution unlikely to reach all individuals in a given area.

Measurement Error!

Focus on systematic pollution by grouping together monitors in multiple counties

Problem:

- There are nearly 1,400 PM 2.5 monitors in the country, but they are sparsely placed.

- Locally produced pollution will generate data noise based on proximity to certain monitors.

- Local pollution unlikely to reach all individuals in a given area.

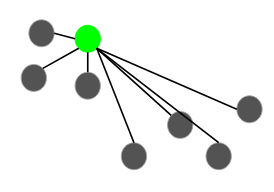

- Unsupervised machine learning technique

- Partitions data around associated centroids, based on the number of clusters k chosen in advance

- Simple method (the "OLS of clustering") of classifying geospatial or even data that might not have interpretable distance (e.g. Spotify songs)

k-means clustering

If we want to be more sophisticated than just picking the monitor groups ourselves...

The algorithm

- (Possibly, especially if not geospatial)

scale and normalize features - Select K points for initial centroids

-

Begin while loop

- Form K clusters by assigning all

points to the closest centroid - Recompute the centroid for each

cluster

- Form K clusters by assigning all

- Stop loop when centroids are stable (usually fairly rapidly but complexity increases in data points, clusters K, and features)

Source: https://github.com/jgscott/ECO395M

The algorithm

- (Possibly, especially if not geospatial)

scale and normalize features - Select K points for initial centroids

-

Begin while loop

- Form K clusters by assigning all

points to the closest centroid - Recompute the centroid for each

cluster

- Form K clusters by assigning all

- Stop loop when centroids are stable (usually fairly rapidly but complexity increases in data points, clusters K, and features)

- Might need to spot-check clusters, if possible

- Each iteration will be different

- Set seed, or

- Use 20+ starts (many packages will choose the start with the lowest within-cluster variation), or

- Use a different initialization strategy K-means++

Some Issues

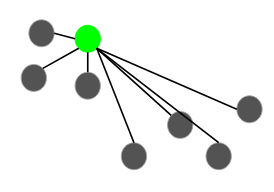

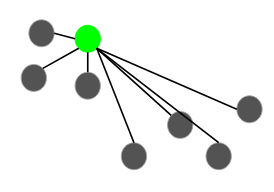

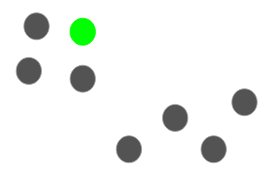

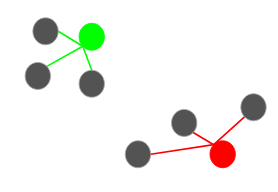

Choose initial

centroid

K-means++

Choose initial

centroid

Compute distance to x's

K-means++

Choose initial

centroid

Compute distance to x's

Probabilistically weight furthest as next centroid

K-means++

Choose initial

centroid

Compute distance to x's

Probabilistically weight furthest as next centroid

Stop when you reach K centroids

K-means++

Source: https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2019/08/comprehensive-guide-k-means-clustering/

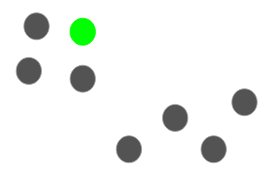

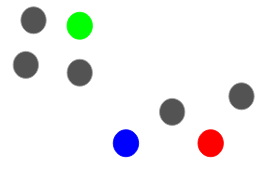

Toy Example

Problem:

- How do we know what is important for how long someone will live?

- We could use some economic intuition to guess, but this is subjective

Problem:

- How do we know what is important for how long someone will live?

- We could use some economic intuition to guess, but this is subjective

- Huge dataset with more than 1000 variables, so simply testing one against another is infeasible

Problem:

- How do we know what is important for how long someone will live?

- We could use some economic intuition to guess, but this is subjective

- Huge dataset with more than 1000 variables, so simply testing one against another is infeasible

Reduce Dimensions

Problem:

- How do we know what is important for how long someone will live?

- We could use some economic intuition to guess, but this is subjective

- Huge dataset with more than 1000 variables, so simply testing one against another is infeasible

Reduce Dimensions

Machine Learning can train on data to select important variables

Problem:

- How do we know what is important for how long someone will live?

- We could use some economic intuition to guess, but this is subjective

- Huge dataset with more than 1000 variables, so simply testing one against another is infeasible

- Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- Makes explicit the tradeoff between choosing covariates to minimize the differences between predicted y and observed y (goodness of fit) and selecting on too many variables (overfitting)

- Can be applied easily to linear regression, proportional hazard, and many other empirical strategies, when it is not clear what is important

LASSO

Solution 1:

LAsso

- LASSO takes the generic form

where dev is closeness of fit and pen is a penalty function on any beta that is non-zero.

- In linear regression using L1 regularization as the penalty, we get a Lagrangian optimization problem that takes the form

How is this Machine Learning?

How is this Machine Learning?

- Chosen value of lambda is data-dependent

- Apply validation tools (e.g. cross-validation to determine optimal value)

How is this Machine Learning?

- Chosen value of lambda is data-dependent

- Apply validation tools (e.g. cross-validation to determine optimal value)

algorithm

- Start with \( \lambda_1 \) so big that any \( \hat{\beta} =0 \)

- For each iteration update \( \hat{\beta} \) to be optimal under \( \lambda_t < \lambda_{t-1} \)

- Use a testing set to pick the best \( \lambda \)

- Need a rule, such as minimum \( \lambda \) or 1se rule (pick the largest \( \lambda \) still within 1 standard error of minimum)

Source: https://github.com/jgscott/ECO395M

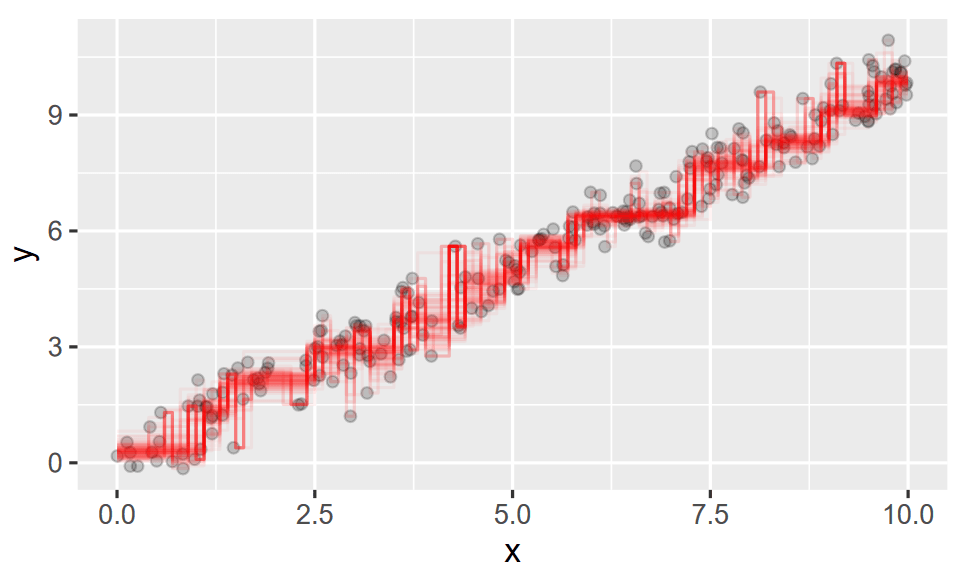

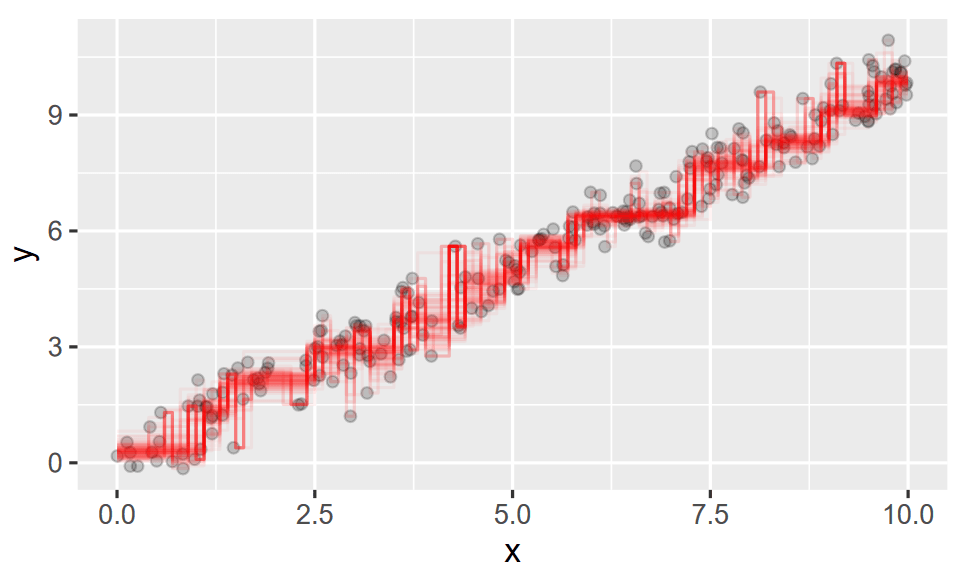

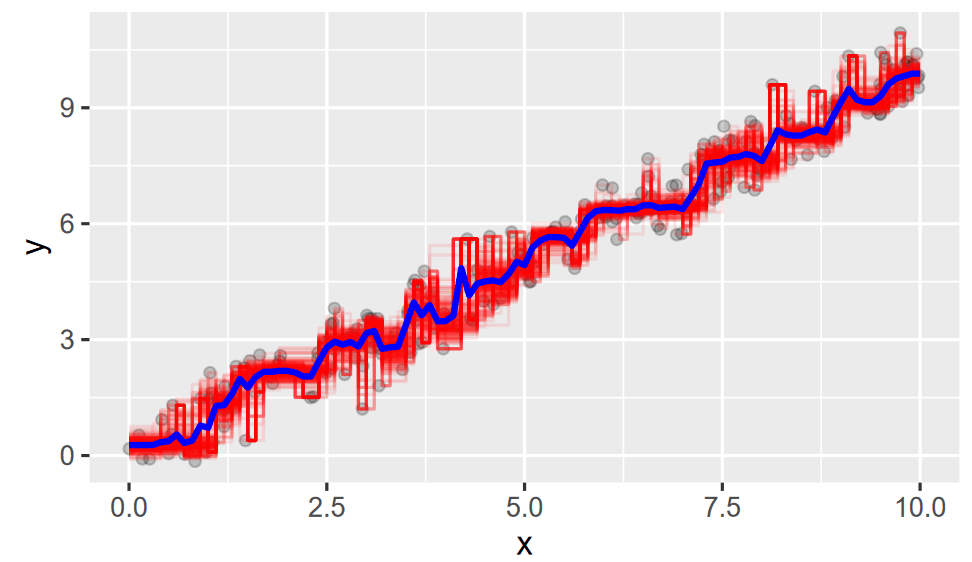

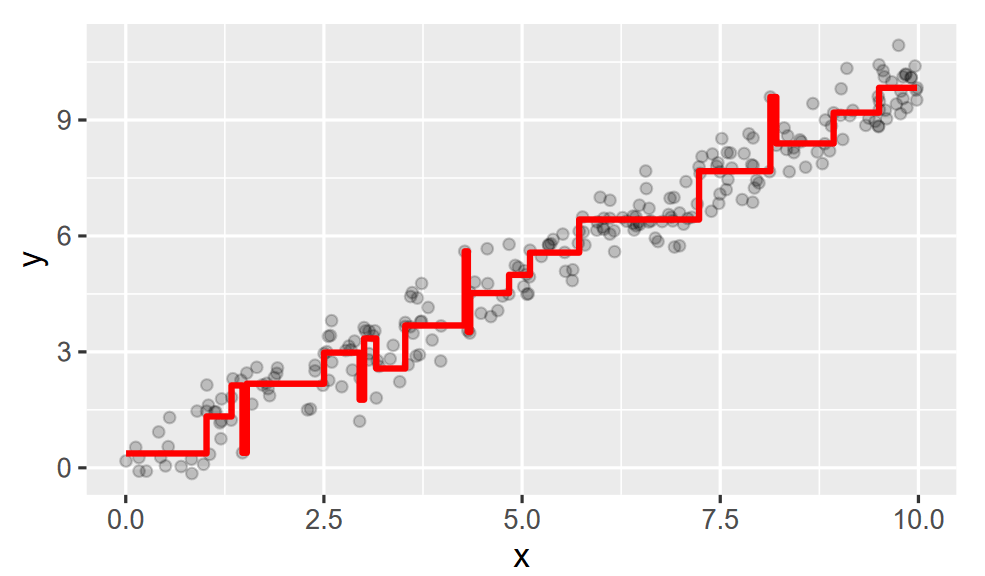

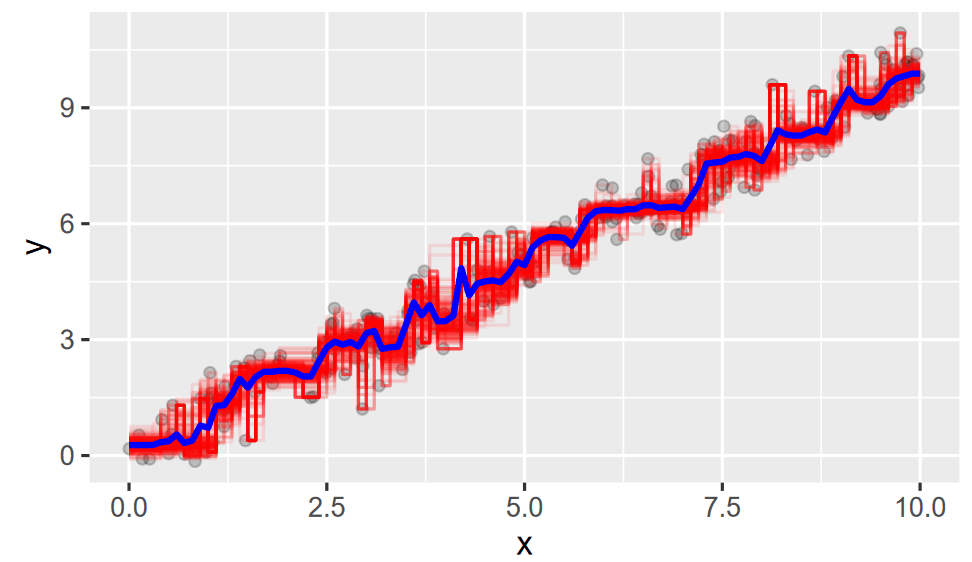

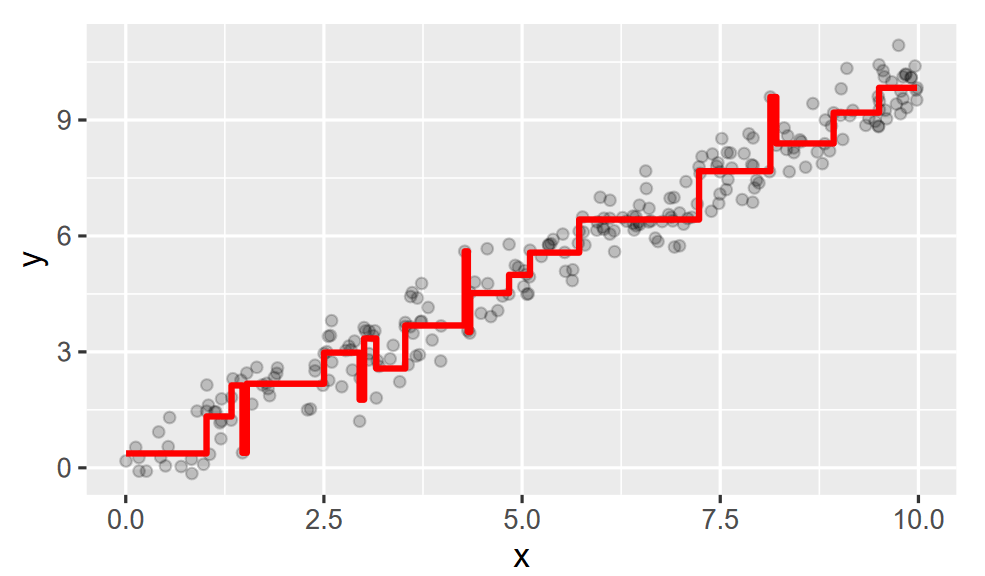

Toy Example

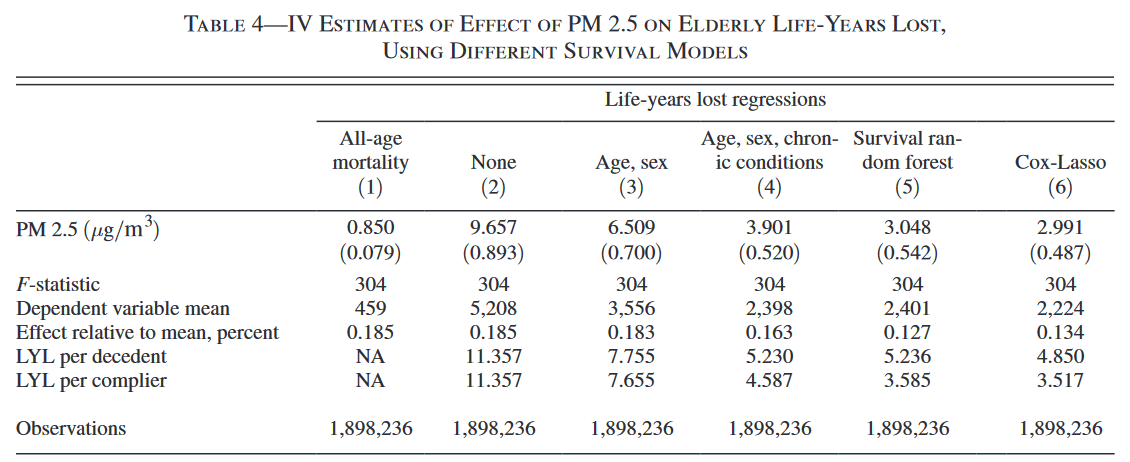

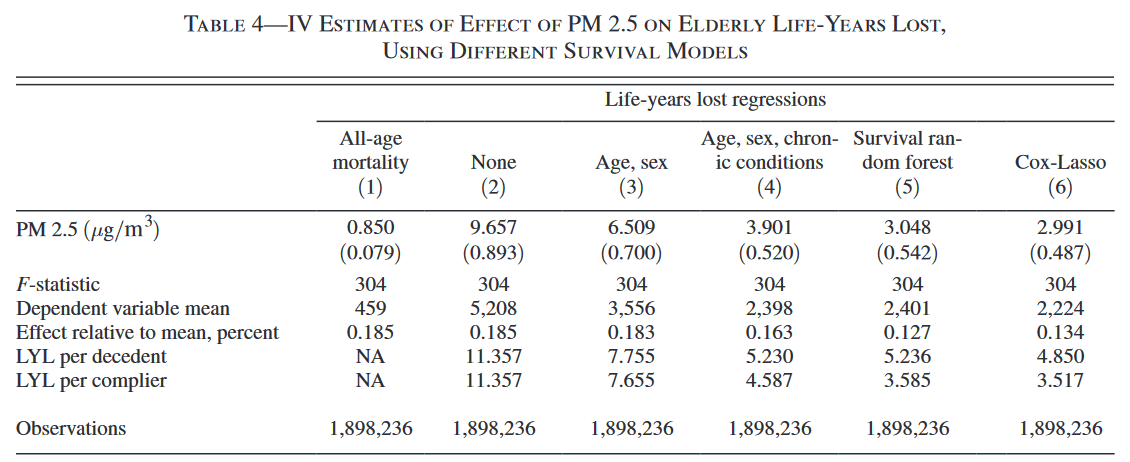

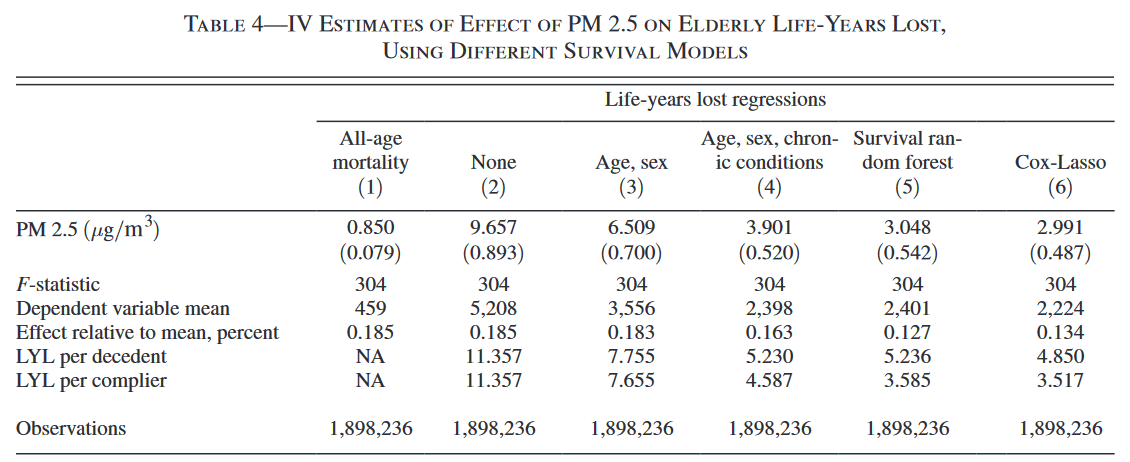

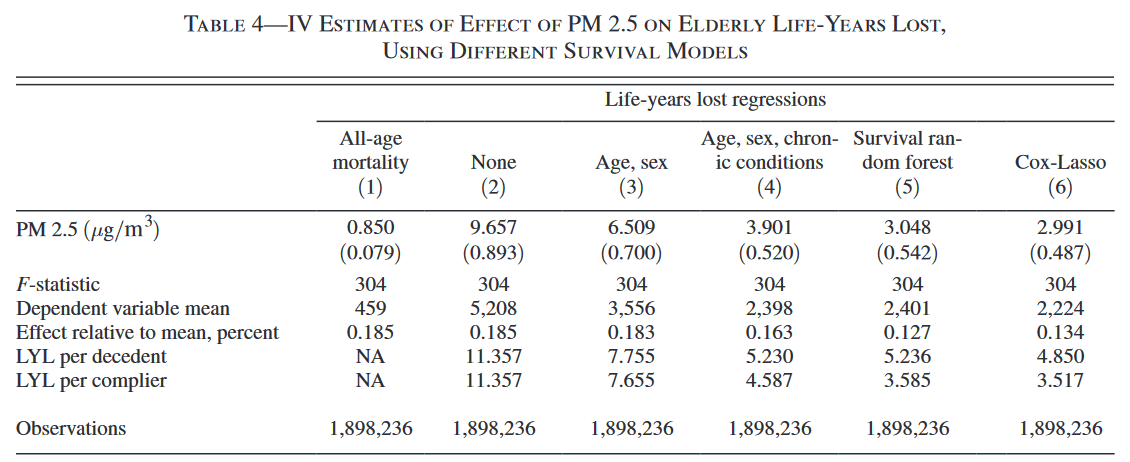

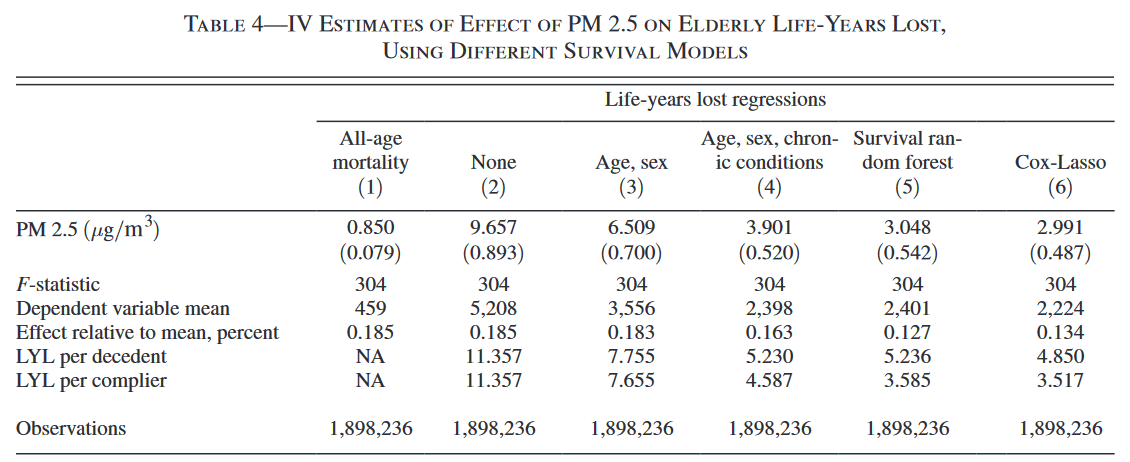

Results

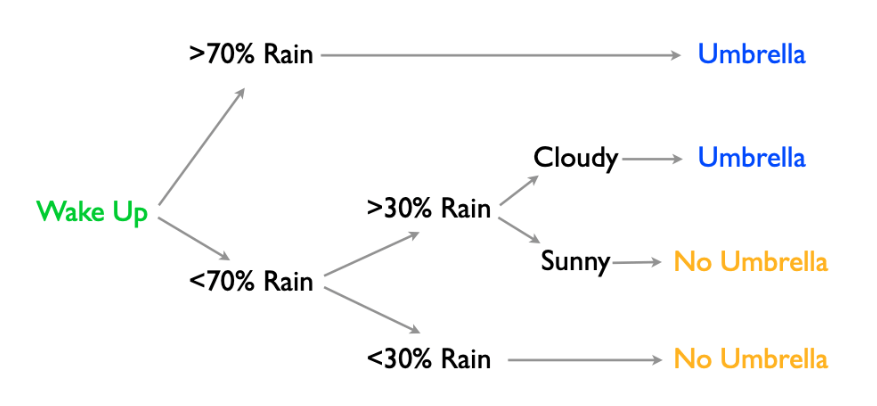

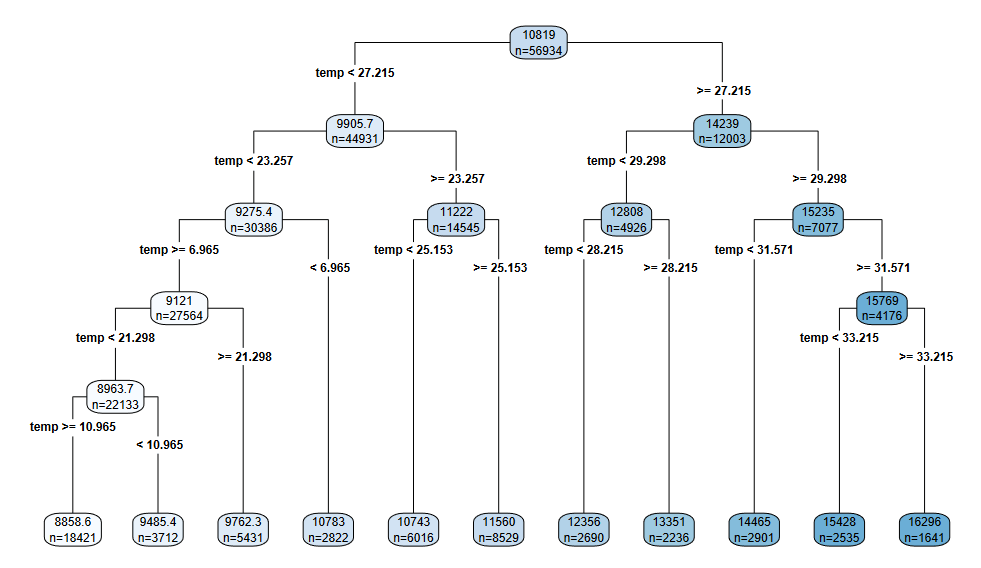

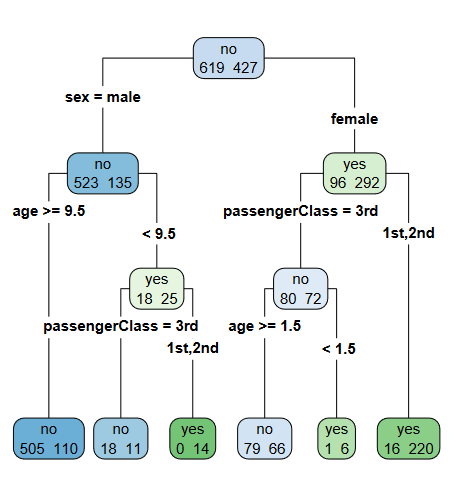

- Trees are sequential decision nodes that branch on inputs to predict the output

Random forest

Solution 2:

Source: https://github.com/jgscott/ECO395M

- Trees are sequential decision nodes that branch on inputs to predict the output

Random forest

Source: https://github.com/jgscott/ECO395M

- Trees are sequential decision nodes that branch on inputs to predict the output

- Based on previous data, use to either

- Categorize: \( P(Y|X) \)

- Estimate: \( E(Y|X) \)

- For numeric x, the decision rule is x<c

Random forest

Source: https://github.com/jgscott/ECO395M

- Trees are sequential decision nodes that branch on inputs to predict the output

- Based on previous data, use to either

- Categorize: \( P(Y|X) \)

- Estimate: \( E(Y|X) \)

- For numeric x, the decision rule is x<c

Random forest

Source: https://github.com/jgscott/ECO395M

- Trees are sequential decision nodes that branch on inputs to predict the output

- Based on previous data, use to either

- Categorize: \( P(Y|X) \)

- Estimate: \( E(Y|X) \)

- For numeric x, the decision rule is x<c

- For categorical x, the rule says a set of categories goes left

Random forest

Source: https://github.com/jgscott/ECO395M

- Trees are sequential decision nodes that branch on inputs to predict the output

- Based on previous data, use to either

- Categorize: \( P(Y|X) \)

- Estimate: \( E(Y|X) \)

- For numeric x, the decision rule is x<c

- For categorical x, the rule says a set of categories goes left

Random forest

Source: https://github.com/jgscott/ECO395M

- Trees are sequential decision nodes that branch on inputs to predict the output

- Based on previous data, use to either

- Categorize: \( P(Y|X) \)

- Estimate: \( E(Y|X) \)

- For numeric x, the decision rule is x<c

- For categorical x, the rule says a set of categories goes left

- The result is a partitioned space that makes choices on inputs and sends them down the tree

Random forest

Source: https://github.com/jgscott/ECO395M

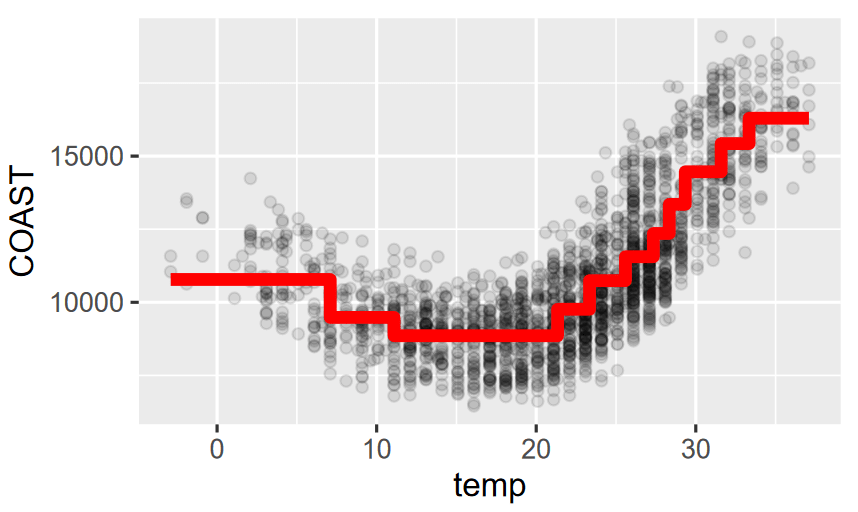

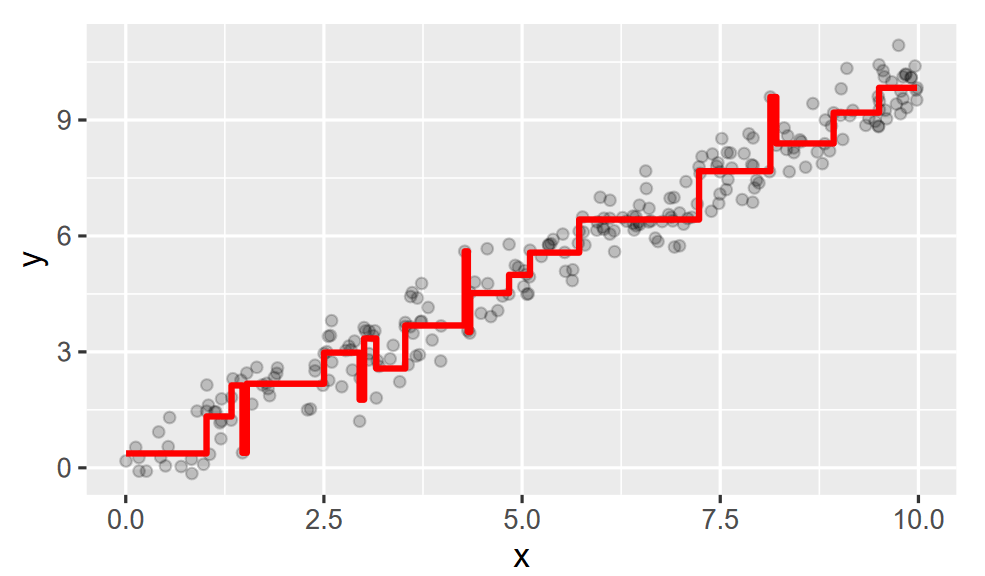

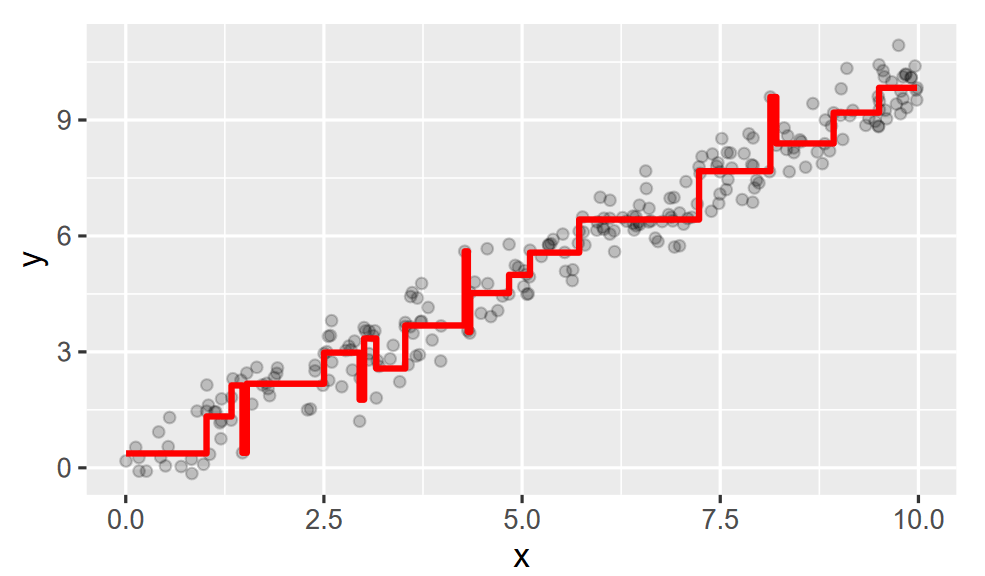

Pruning Trees

- Trees are always step functions

Pruning Trees

- Trees are always step functions

Pruning Trees

- Trees are always step functions

- They always consider interaction terms and nonlinearities (automatically because each node considers past nodes)

- It also automatically ignore unimportant variables because they never increase fit

- Pros: fast to fit, interpretable, and easily switch between numeric and categorical variables

- Cons: don't scale well, each individual tree can be quite bad at predicting against the testing set

- We'll need to prune!

Pruning Trees

- Grow big:

- Search over each possible splitting rule for the one that gives the biggest increase in fit

- Stop once you reach a minimum threshold (e.g. we only have 10 observations per leaf)

- This is probably overfitted!

- Prune back

- Search over all chosen splits for the one that is the least useful split for goodness of fit

- Stop when you have only a single node

- This has lost most explanatory power!

- But these two processes give a sequence of trees that each of a bias-variance tradeoff that can be cross-validated

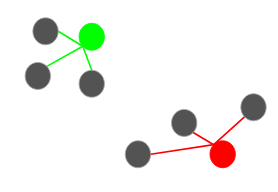

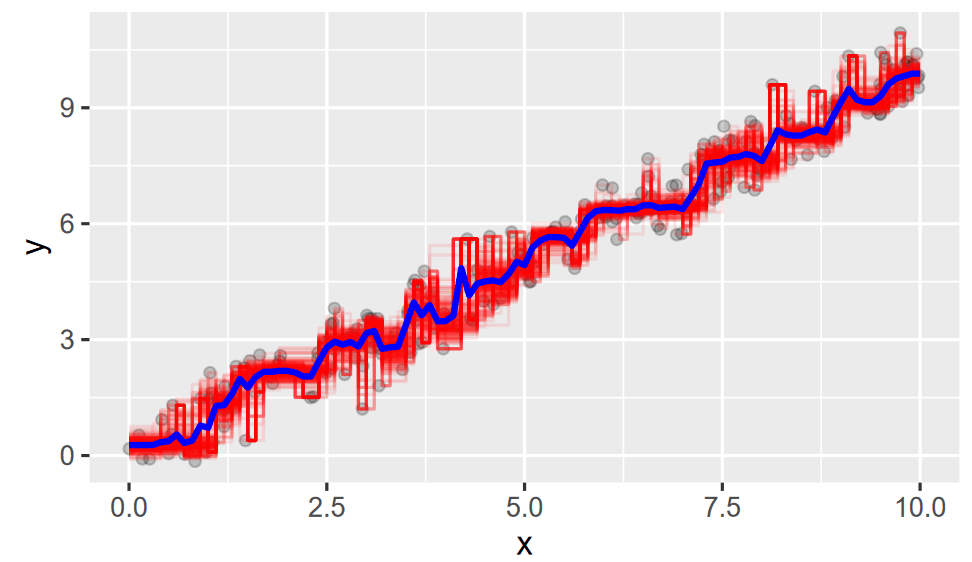

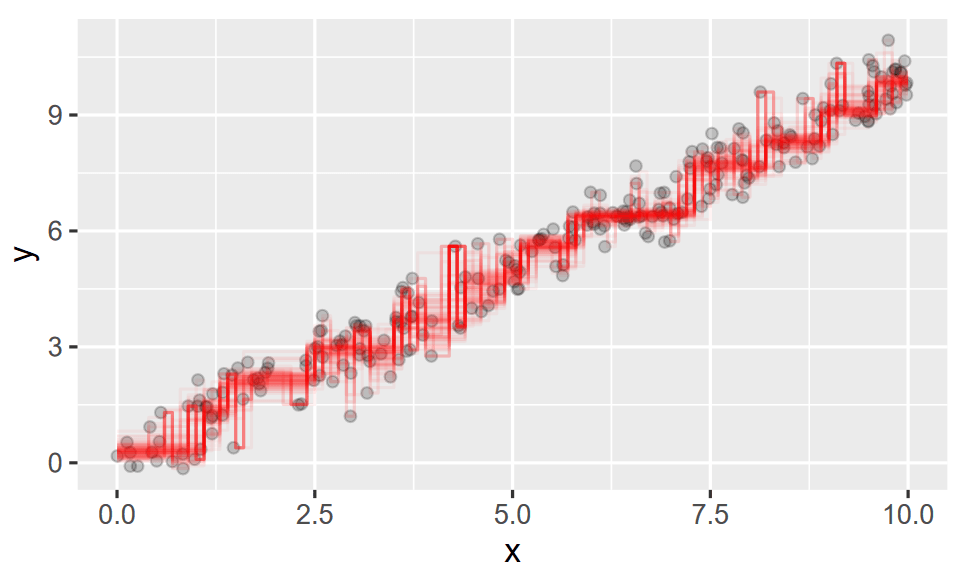

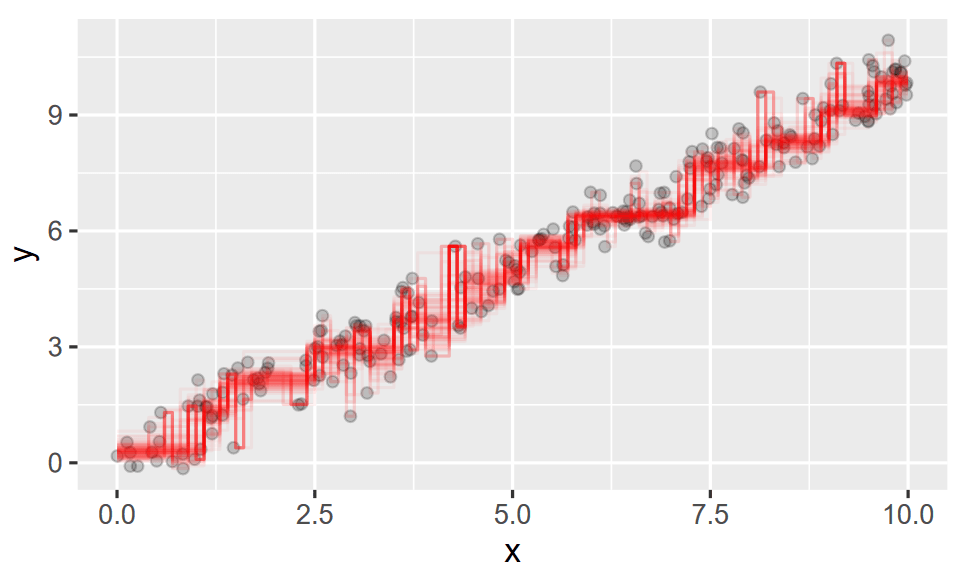

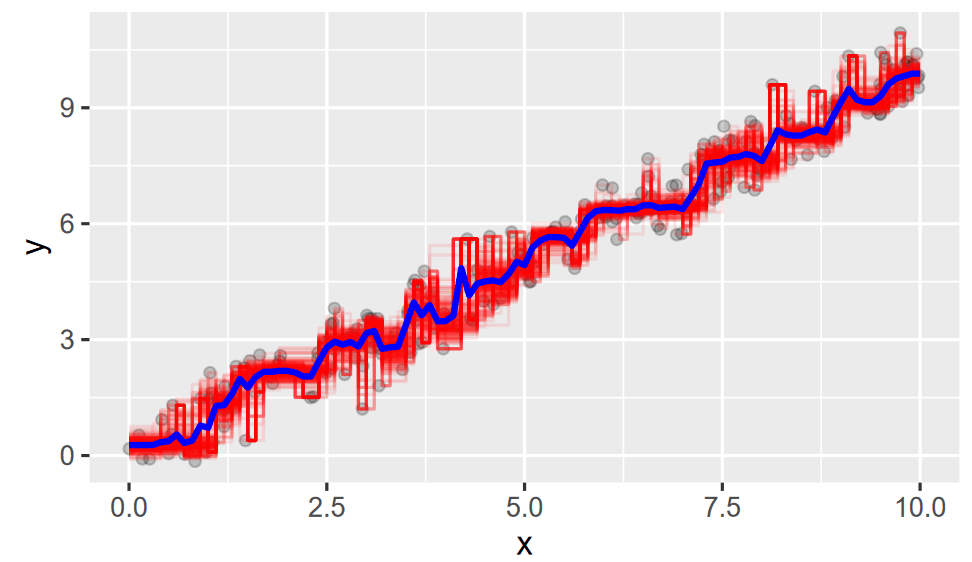

Seeing the Forest

- Bootstrap aggregate ("bagging") over a huge collection of big and pruned trees to get a large selection of trees

- Take the average of those trees and you get the forest

Seeing the Forest

- Bootstrap aggregate ("bagging") over a huge collection of big and pruned trees to get a large selection of trees

- Take the average of those trees and you get the forest

Seeing the Forest

- Bootstrap aggregate ("bagging") over a huge collection of big and pruned trees to get a large selection of trees

- Take the average of those trees and you get the forest

Seeing the Forest

- Bootstrap aggregate ("bagging") over a huge collection of big and pruned trees to get a large selection of trees

- Take the average of those trees and you get the forest

Toy Example

Results

Results

"The richness of our controls suggest this final estimate is about as good a representation of the true value as can be obtained empirically."

Results

"This drop indicates that mortality effects of PM 2.5 tend to be larger among individuals with characteristics that Cox-Lasso associates with lower life expectancy, even after conditioning on age, sex, and chronic conditions."

machine_learning_PM25

By bjw95

machine_learning_PM25

- 93