Public Goods

and Public Choice

Christopher Makler

Stanford University Department of Economics

Econ 51: Lecture 19

Today's Agenda

Hour 1: Optimal Provision

Hour 2: Social Choice

Classifying goods: rival/excludable

When to provide a public good

How much of a public good to provide

Funding mechanisms

Voluntary contribution and Free Riding

Voting over public goods

Classifying Goods

Rivalry in Consumption

One agent's consumption affects others' ability to consume it the same good.

Excludability

Agents may be prevented from consuming the good

Rival

Nonrival

Excludable

Nonexcludable

Private Goods

Common Resources

Public Goods

Club Goods

These aren't hard-and-fast categories

- Interstate 280 at 4am is a public good (nonrival, nonexcludable)

- Interstate 280 at 4pm is a common resource (rival, nonexcludable)

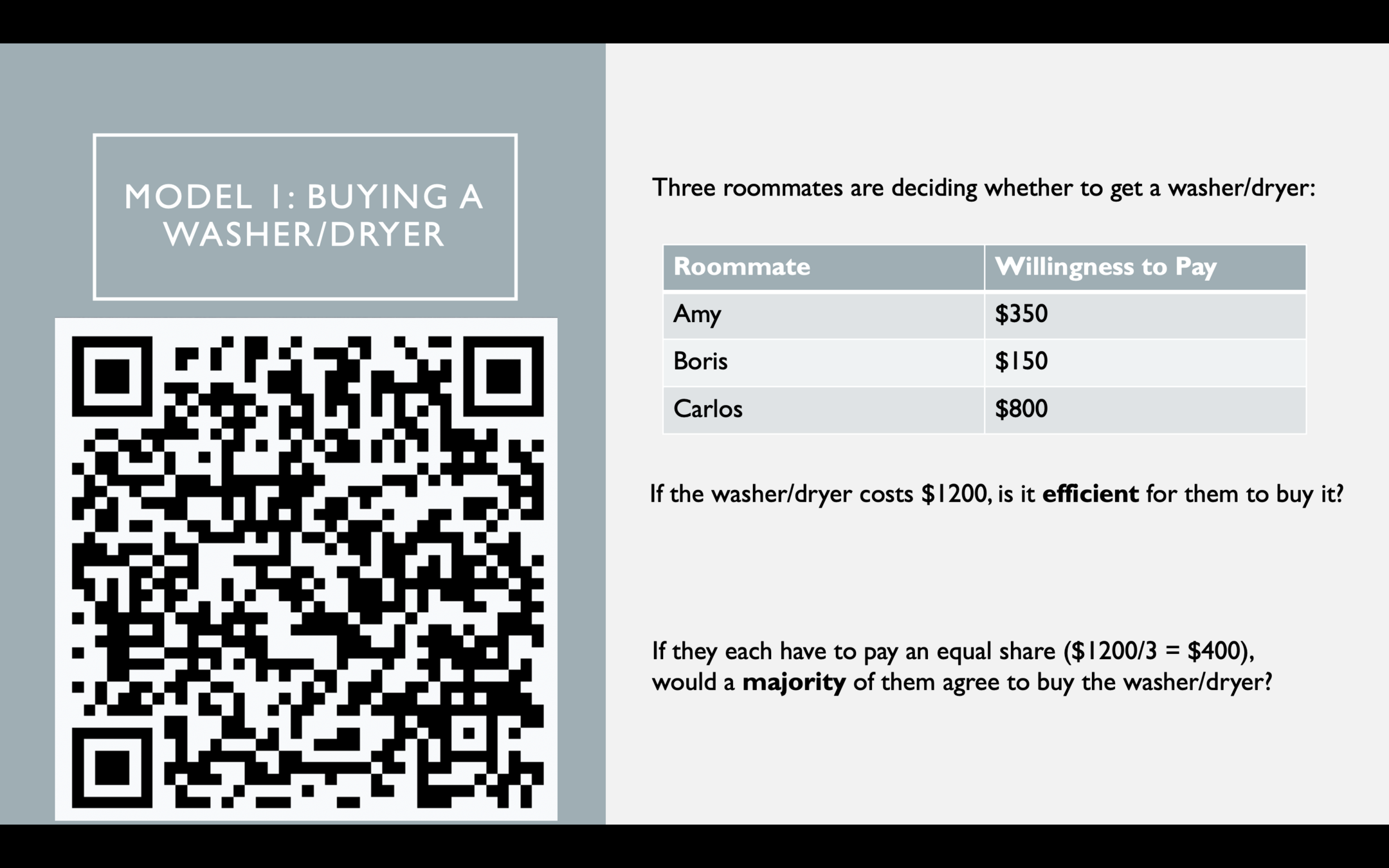

When to Provide a Public Good

How Much Public Good to Provide

When the benefits of a good accrue to everyone,

everyone has an incentive to shirk their contribution

Model 2: Voluntary Contribution to a Public Good, and the Free Rider Problem

Two people, 1 and 2, can contribute to a public good. Each has income \(m = 12\).

Write payoffs in terms of strategies:

Write payoffs in terms of strategies:

We could start to write out a payoff matrix...

but the strategy space is continuous so we could never list out every possible (real number) contribution.

Instead, let's think about a best response function

What is player 1's best response to player 2 choosing to contribute some amount \(g_2\)?

Write payoffs in terms of strategies:

Solve for each player's best response function

What is player 1's best response to player 2 choosing to contribute some amount \(g_2\)?

To maximize give the other's strategy, take the derivative of your payoff function

with respect to your own strategy and set it equal to zero:

BEST RESPONSE FUNCTIONS

BEST RESPONSE FUNCTIONS

In a Nash equilibrium, each player is choosing a strategy which is a best response to the other's strategy.

To solve, plug one's BR into the other:

BEST RESPONSE FUNCTIONS

In a Nash equilibrium, each player is choosing a strategy which is a best response to the other's strategy.

To solve, plug one's BR into the other:

Could they both do better?

What would a social planner do?

Private goods: aggregate preferences by summing demand curves horizontally.

Public goods: aggregate preferences by summing demand curves vertically.

Since the demand curve represents the MRS, this means the efficient amount to produce is where the sum of the MRS's equals the cost.

Model 3: A Fireworks Show

A town is preparing to have a fireworks show.

Let \(G\) be the total number of minutes of fireworks

Each minute of fireworks costs $200.

Model 3: A Fireworks Show

A town is preparing to have a fireworks show.

Let \(G\) be the total number of minutes of fireworks

Let \(g_i \ge 0\) be the amount citizen \(i\) contributes to the show;

each person has income \(m_i\), so their private consumption is \(x_i = m_i - g_i\).

Each minute of fireworks costs $200.

There are two types of citizen:

200 kinda love fireworks

Note: \(x_i\) is private consumption (dollars left over after contributing \(g_i\)) so we can also write

100 really love fireworks

\(G\) = total number of minutes of fireworks

\(g_i \ge 0\) = amount citizen \(i\) contributes

Each minute of fireworks costs $200

There are two types of citizen:

100 really love fireworks

200 kinda love fireworks

Questions:

What is the efficient length of a fireworks show?

What is the fairest way to pay for the fireworks?

How can the town decide how long of a show to have?

\(G\) = total number of minutes of fireworks

\(g_i \ge 0\) = amount citizen \(i\) contributes

100 really love fireworks

200 kinda love fireworks

What is the efficient length of a fireworks show?

Cost

"Samuelson Condition" : set the sum of the MB's equal to the MC:

\(G\) = total number of minutes of fireworks

\(g_i \ge 0\) = amount citizen \(i\) contributes

100 really love fireworks

200 kinda love fireworks

What is the efficient length of a fireworks show?

Cost

Suppose everyone else had contributed some amount \(G\).

How much would each type voluntarily contribute?

For example, suppose everyone else had contributed enough for a 4-minute-long show.

What is the marginal benefit of each type?

This is called the free rider problem.

\(G\) = total number of minutes of fireworks

\(g_i \ge 0\) = amount citizen \(i\) contributes

100 really love fireworks

200 kinda love fireworks

What mechanism can achieve the efficient quantity of \(G^* = 25\)?

Cost

Suppose you knew everyone's type, and could charge them differently.

You could charge everyone half their valuation:

$30 for people who love fireworks, $10 for people who kinda love fireworks.

What's the problem with this?

\(G\) = total number of minutes of fireworks

\(g_i \ge 0\) = amount citizen \(i\) contributes

100 really love fireworks

200 kinda love fireworks

Suppose people voted on the fireworks show. There are 300 people, so \(G = 300g/200 = 3g_i/2\)

What would a majority vote for?

Social Choice

To navigate: press "N" to move forward and "P" to move back.

To see an outline, press "ESC". Topics are arranged in columns.

Big Ideas

We're going from individual choice to social choice.

Up to now we've had an individual agent choosing something.

Societies also make choices: how much to tax and spend, who to lead them, etc.

How do we evaluate mechanisms for aggregating preferences?

It's "impossible" to find an aggregation method that works in general.

However, under certain more restrictive assumptions on preferences,

some mechanisms will work better than others, with predictable outcomes.

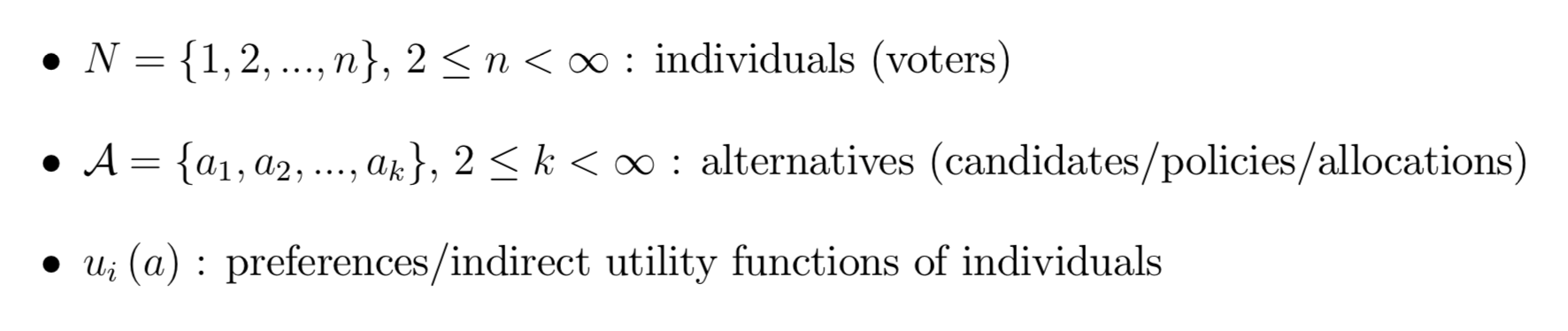

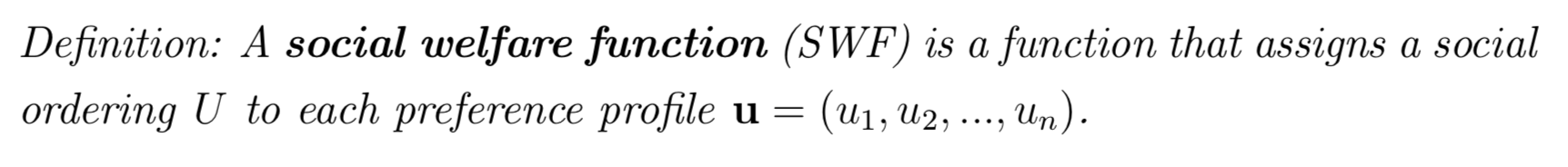

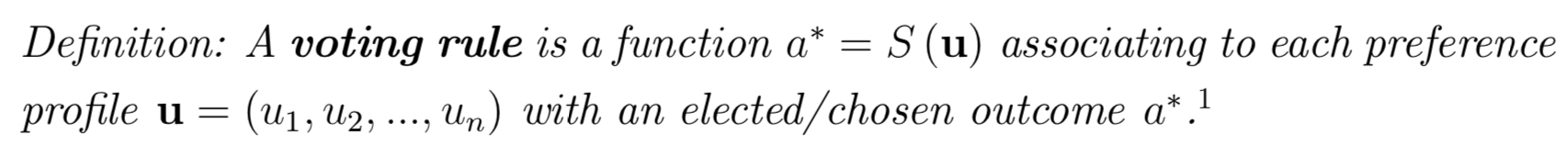

From Social Preferences to Social Choice

Terminology

A SWF ranks all possible alternatives:

e.g., has indifference curves within the Edgeworth Box

Just needs to pick a winner;

sometimes called a Social Choice Function (SCF)

Arrow's Impossibility Theorem

Desirable Properties of a Social Welfare Function

- Non-dictatorship: it isn't just simply the preferences of one dictator.

- Unanimity: if everyone likes A better then B, then society cannot prefer B to A.

- Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives: if society prefers A to B when C isn't an option, it cannot prefer B to A when C is an option.

Arrow's Theorem: There is no complete and transitive SWF that satisfies all three of these.

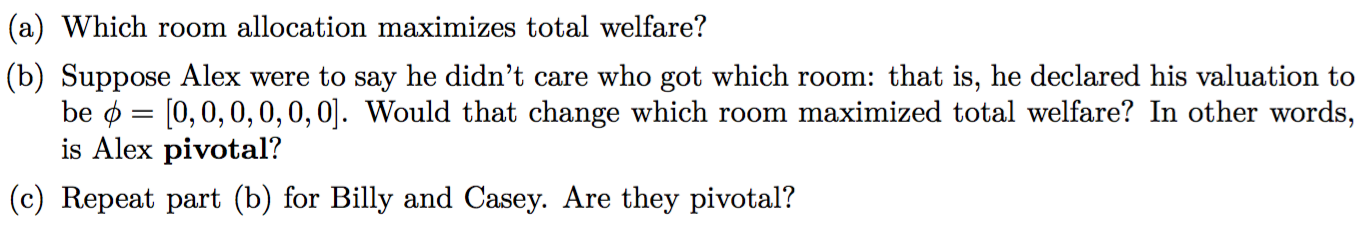

Example: Failure of Majority Rule

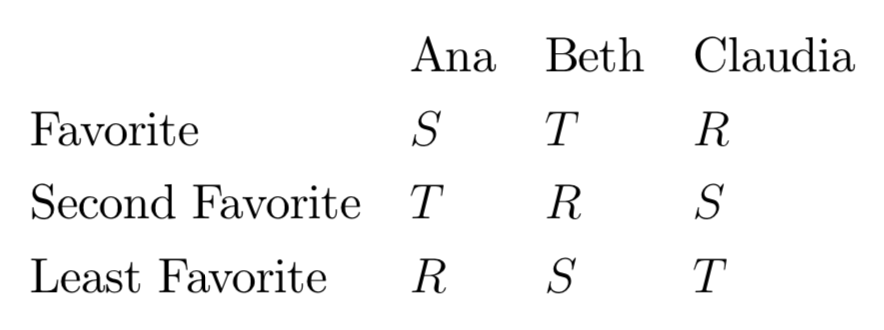

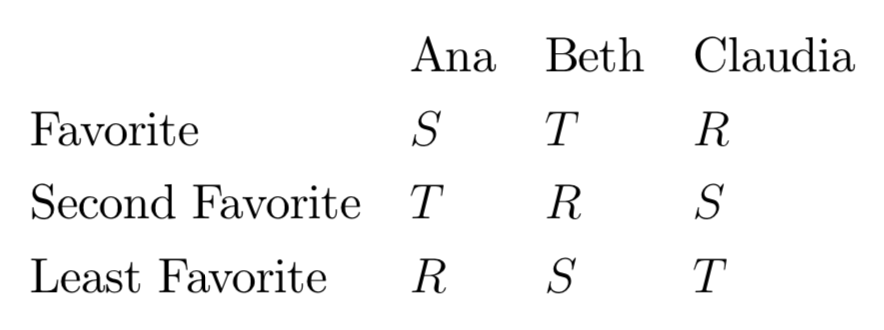

Ana, Beth, and Claudia are buying a television.

They can buy an RCA (R), Sony (S), or Toshiba (T).

Their preference rankings are given by the following:

Suppose we were to create a social preference ordering by pairwise ranking each alternative, choosing the preferred one by majority rule.

Then society prefers R to S...

and S to T...

and T to R...

which isn't transitive!

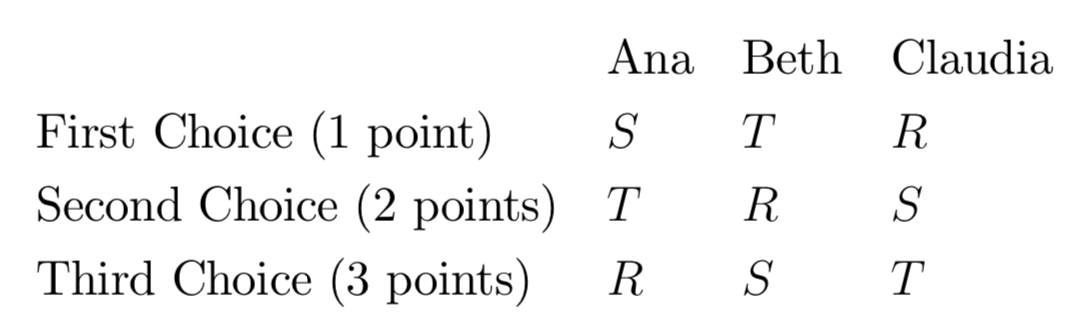

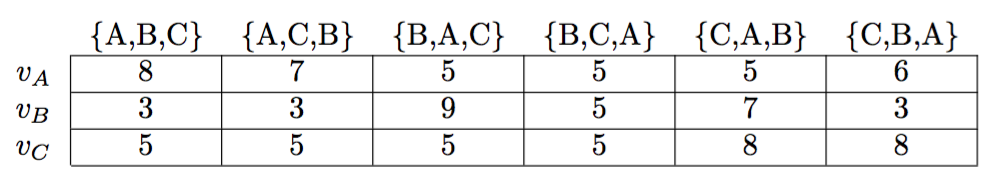

Another Mechanism: Borda Count

Let's assign a point value to your choice ranking:

Now we see that this is a tie: each gets 6 points.

But now let's look to see what happens if there's a fourth option, a Zenith:

Now R has 6 points, but S and T have 7. So the introduction of Z changes the preferences over

R, S, T => violates the independence of irrelevant alternatives axiom.

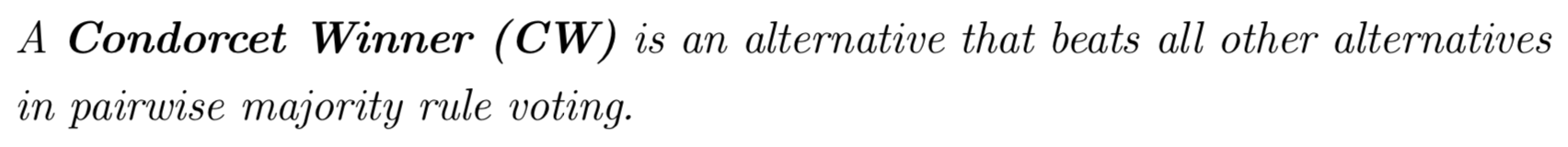

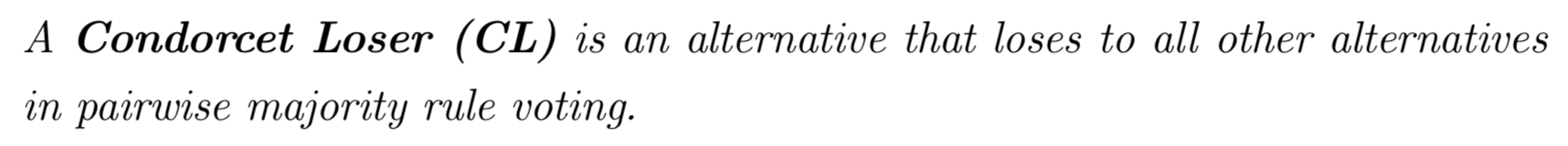

The Condorcet Paradox

As in the TV question, a CW or CL may not always exist, which can result in a voting cycle!

If you set the voting rule,

you can choose the winner.

| Voting Rule | Winner |

|---|---|

| S vs T, then winner vs. R | R |

| R vs T, then winner vs. S | S |

| S vs R, then winner vs. T | T |

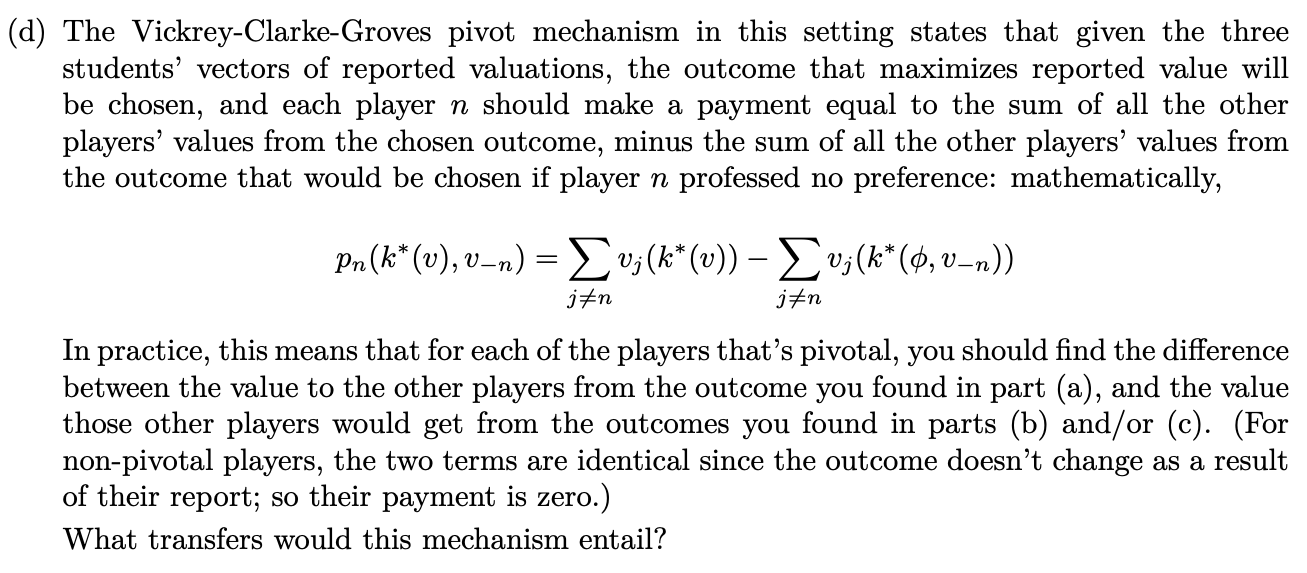

I do not expect you to solve a VCG problem on the final exam; however, it is fair game to ask what problem it is trying to solve,

and its approach to solving that problem.

Note

The VCG Mechanism

General class of problems: a group of people with

private information has to make a collective choice.

For example: suppose three roommates are moving into a new apartment,

so there are 6 possible ways they could be assigned to rooms.

They each have preferences over all 6 possible combinations.

How can they decide who gets which room?

General Formulation

There are people \(i = 1,...,N\) and possible decisions \(k = 1,...,K\).

Person \(i\) would get payoff \(v_{ik}\) if option \(k\) is chosen.

The goal is to collect accurate information about individual values and pick the decision \(k^*\) that maximizes the total value:

A direct mechanism asks each person to report their values for each outcome and select the one that maximizes total welfare.

\(W(k) = v_{1k} + \cdots + v_{Nk}\)

Each player can, by its report, force the selection of any outcome, so why would it always choose \(k^*\)?

Goal: align payoffs of individuals with the total social payoff.

Mechanism: define a series of transfer payments based on stated valuations that encourage truthful revelation of value.

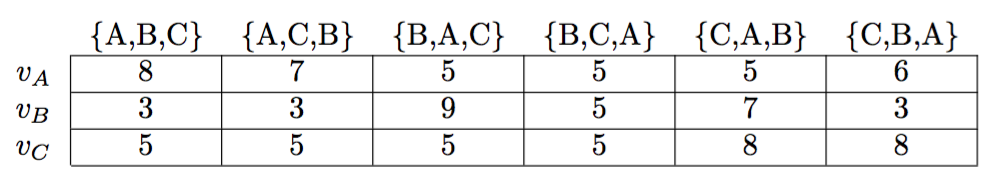

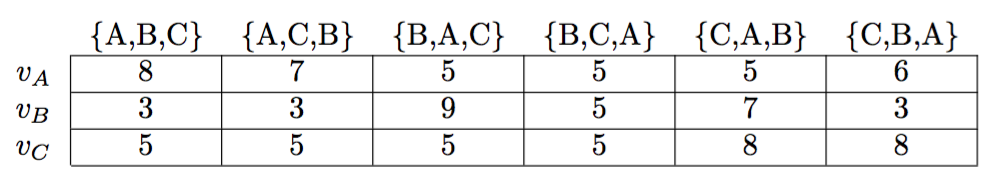

Vickrey-Clarke-Groves Mechanism

1. Each player reports their vector of values for each of the \(K\) alternatives: \(v_i = (v_{i1}, ... , v_{iK})\). They can lie if they want.

3. When the "center" chooses \(k\), it pays player \(i\):

Analysis of incentives: player \(i\) wants to induce the center to choose the \(k\) that maximizes:

2. The "center" selects the \(k^*\) that maximizes the total reported value.

They do this by reporting truthfully!

A player is said to be pivotal when its reported vector of values

changes the outcome of the mechanism,

compared to the case in which they didn't participate

(i.e., reported just a vector of zeroes).

In a pivot mechanism, only the pivotal players have a side payment.

In particular, they have to pay the amount

by which they change other people's (reported) utility.

Thoughts on the Last 20 Weeks

Thank You

Econ 51 | 21 | Public Goods

By Chris Makler

Econ 51 | 21 | Public Goods

- 829