Welcome to Econ 51

To navigate: press "N" to move forward and "P" to move back.

To see an outline, press "ESC". Topics are arranged in columns.

Today's Agenda

Part 1: Course Overview

Part 2: Review of Econ 50

Introductions and Welcome

Three Themes and a Goal

Class Organization and Policies

Unit Overview

Budget sets and Preferences

Constrained Optimization

Specific Utility Functions

Demand and Offer Curves

To Do Before Next Class

Introductions and Welcome

Chris Makler

- B.A.: Humanities, Yale

- Ph.D.: Economics, Penn

(search & matching theory)

- 10 years in the education technology industry

- Sixth time teaching Econ 51

- Office: Landau Econ Building, Room 144

Welcome to Econ 51!

TA Introductions

Sharon

Andy

Econ Department Peer Advising

Other Resources

VPTL Peer Tutoring

Three Themes and a Goal

Theme I: Efficiency and Equity

Why does the market system lead to efficient but

(potentially) inequitable allocations of goods?

Move from looking at bundles of good for a single individual to allocations of goods across individuals.

Under what kinds of circumstances does

everyone solving their own optimization problem

not lead to efficient outcomes?

Theme II: Time

(1) We'll treat "good 1" as "consumption now" and "good 2" as "consumption later" and apply the usual consumer model to "intertemporal choice" models of borrowing and saving.

In Econ 50 we looked only at "static" models in which people were making a decision at a single point in time.

In Econ 51 we'll think of time in two ways:

(2) We'll look at sequential and repeated games, in which players don't move at the same time, but respond to each others' past moves.

Theme III: Information

(1) We'll treat "good 1" as "consumption in one state of the work" and "good 2" as "consumption in another state of the world" and apply the usual consumer model to analyze "risk aversion" and models of insurance and diversification.

In Econ 50 we looked only at "deterministic" models in which everyone had all relevant information about each transaction.

In Econ 51 we'll think of information in two ways:

(2) We'll look at games of incomplete information, when players don't know other players' payoffs or actions.

Overall Goal of the Course:

Refine the Toolset of Econ 50 for More Realistic Applications

Econ 1

Econ 50

Econ 51

Finance

Labor and Education

Public Goods and Optimal Tax

Environmental Economics

Strategic Competition

Auctions and Market Design

Vocabulary

Tools

Refinements

Applied Micro Field Courses

Optimization

Comparative

Statics

Equilibrium

Efficiency

Time

Information

Applications

Micro/Macro

Supply and Demand

Scarcity and Choice

Class Organization

Before Lecture

- Do the reading

- Take online quizzes (easy!)

- 5% of grade

- Graded for correctness, not just completion

Lecture

- Estabish motivation and context

- Work through simple examples

Homework

- Apply concepts from lecture to new situations, more complex examples

- Full credit: earn 100 points in 10 weeks

- 20% of grade

Exams

-

Midterm: Units I & II

(30% of grade) -

Final: Units III & IV

(45% of grade)

[declarative]

[strategic/

schematic]

[procedural]

[cumulative]

Homework Policy

-

Exercises are posted after each lecture, and should be uploaded to Canvas by midnight a few days later. (Tuesday lectures are due Friday night, Thursday lectures are due Monday night.) Solutions are posted at 8am, so homeworks uploaded after 8am are not accepted.

-

Old exam questions are included in each problem set to give you extra practice and help prepare for tests.

-

Each exercise or old exam problem is worth 3-5 points. Your goal is to earn at least 100 pointsfor the quarter (about 10 points per week). Earning beyond 100 points doesn't help your grade, but earning below 100 points will hurt it.

-

Goal: everyone gets 100% homework grade, in the most useful way for them.

Use the problem sets to identify which areas you've got down cold, and which you need more help with. Earn needed points by doing old exam questions on areas you find hard. -

Don't stop when you reach 100 points! Doing exercises is how you learn; people who stop at 100 points tend to do worse on the final by about one letter grade.

Intermediate Microeconomics

by Hal Varian

(Edition is unimportant.)

Strategy

by Joel Watson

No Electronics in Lecture

No phones.

No tablets.

No laptops.

No video or audio recording.

Missing Work

Quizzes

Exercises

Exams

Drop lowest three scores

You just need to earn 100 points over the quarter.

Illness or emergency: contact me before the test starts.

If you do less on one assignment, just do more on another!

Unit Overview

Unit II

The Edgeworth Box and Efficiency

Tuesday 4/30

Midterm on Units I and II

Unit III

Games with Full Information

Unit IV

Bayesian Games and Mechanism Design

Tuesday 6/11

Final Exam on Units III and IV

Course Units (4-5 lectures each)

Unit I

Optimization from an Endowment

[10 minute break]

Sign up for Piazza.

Budget Sets

Good 1 - Good 2 Space

Two "Goods" : Good 1 and Good 2

A "consumption bundle" is a pair of quantities.

Budget Constraint

GOOD 1

GOOD 2

Preferences

Every consumption bundle has a cost.

Given a bundle and prices,

we can divide the choice space

into "more expensive" and

"less expensive bundles.

Given a bundle and preferences,

we can divide the choice space

into "preferred" and

"dispreferred" bundles.

Every consumption bundle has a benefit.

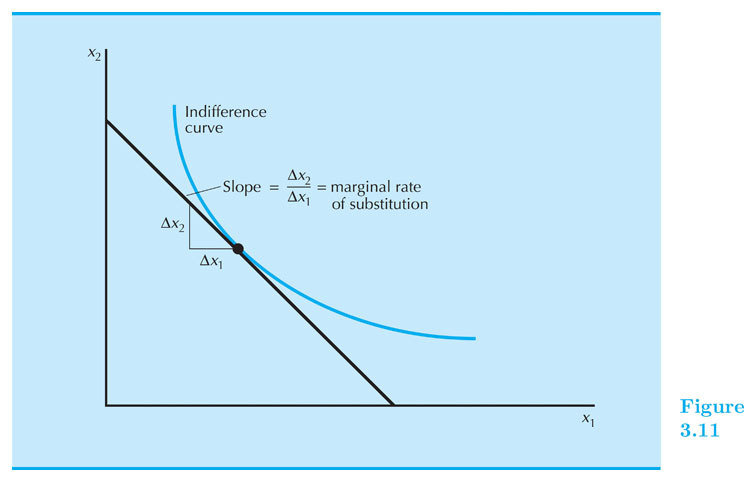

MRS: Slope of the Indifference Curve

"How many units of good 2 are you willing to give up

to get another unit of good 1?"

"How much good 2 would I need to give you

in order to give up one unit of good 1?"

Or, in the special case where good 1 is "this good"

and good 2 is "dollars spent on other things:"

"How much money (

i.e., units of good 2) would you be willing to pay

for an additional unit of this good (

i.e., good 1)?"

(or equivalently)

The “Gravitational Pull"

Towards Optimality

Indifference curve is

steeper than the budget line

Indifference curve is

flatter than the budget line

Moving to the right

along the budget line

would increase utility.

Moving to the left

along the budget line

would increase utility.

More willing to give up good 2

than the market requires.

Less willing to give up good 2

than the market requires.

GOOD 1

GOOD 2

IF...

THEN...

The consumer's utility function is "well behaved" -- smooth, strictly convex, and strictly monotonic

The indifference curves do not cross the axes

The budget line is a simple straight line

The optimal consumption bundle will be characterized by two equations:

More generally: the optimal bundle may be found using the Lagrange method

- Write an equation for the tangency condition.

- Write an equation for the budget line.

- Solve for x1* or x2*.

- Plug value from (3) into either equation (1) or (2).

Procedure for Solving a Well-Behaved Optimal Choice Problem

When not well-behaved: use logic!

Utility Functions

We'll focus on three "forms" of utility functions:

Weighted average of some common "one-good" utility function v(x):

"Quasilinear": one good enters linearly

(in this case \(x_2\)), another nonlinearly:

Perfect complements:

not used as often, but helpful

Cobb-Douglas (decreasing MRS)

Weak Substitutes (decreasing MRS)

Perfect Substitutes (constant MRS)

Concave (increasing MRS)

Quasilinear

Demand and Offer Curves

(Gross) Demand Functions

Demand Curve for Good 1

Price Offer Curve for Good 1

Demand curves show the functional relationships between price and quantity demanded.

Offer curves show sets of possible endogenous variables.

(Gross) demand functions are mathematical expressions

of endogenous choices as a function of exogenous variables (prices, income).

To Do Before Next Class

Be sure you're signed up for a section.

Do the reading and the quiz -- due at 11:15am on Thursday!

Read the syllabus carefully.

Look over the summary notes for this class.

Econ 51 | 01 | Welcome to Econ 51

By Chris Makler

Econ 51 | 01 | Welcome to Econ 51

Welcome to Econ 51

- 2,046