COMP2511

24T2 Week 4

Wednesday 2PM - 5PM (W14A)

Thursday 11AM - 2PM (H11A)

Slides by Christian Tolentino (z5420628)

Make sure to fill in the assignment 1 pair preference form!

Today

- Law of Demeter

- Liskov Substitution Principle

- Design by Contract

- Streams & Lambdas

Law of Demeter

"Principle of least knowledge"

Law of Demeter

What is it?

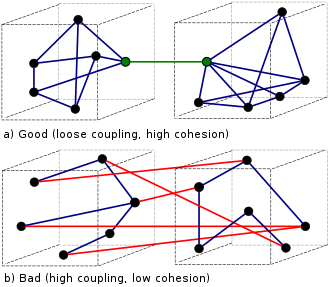

Law of Demeter (aka principle of least knowledge) is a design guideline that says that an object should assume as little as possible knowledge about the structures or properties of other objects.

It aims to achieve loose coupling in code.

Law of Demeter

What does it actually mean?

A method in an object should only invoke methods of:

- The object itself

- The object passed in as a parameter to the method

- Objects instantiated within the method

- Any component objects

- And not those of objects returned by a method

E.g., don't do this

o.get(name).get(thing).remove(node)This is not a hard-and-fast rule. Sometimes it is unavoidable.

Code Review

Law of Demeter

Code Review

In the unsw.training package there is some skeleton code for a training system.

- Every employee must attend a whole day training seminar run by a qualified trainer

- Each trainer is running multiple seminars with no more than 10 attendees per seminar

In the TrainingSystem class there is a method to book a seminar for an employee given the dates on which they are available. This method violates the principle of least knowledge (Law of Demeter).

Code Review

In the unsw.training package there is some skeleton code for a training system.

- Every employee must attend a whole day training seminar run by a qualified trainer

- Each trainer is running multiple seminars with no more than 10 attendees per seminar

In the TrainingSystem class there is a method to book a seminar for an employee given the dates on which they are available. This method violates the principle of least knowledge (Law of Demeter).

/**

* An online seminar is a video that can be viewed at any time by employees. A

* record is kept of which employees have watched the seminar.

*/

public class OnlineSeminar extends Seminar {

private String videoURL;

private List<String> watched;

}

/**

* An in person all day seminar with a maximum of 10 attendees.

*/

public class Seminar {

private LocalDate start;

private List<String> attendees;

public LocalDate getStart() {

return start;

}

public List<String> getAttendees() {

return attendees;

}

}

public class TrainingSystem {

private List<Trainer> trainers;

public LocalDate bookTraining(String employee, List<LocalDate> availability) {

for (Trainer trainer : trainers) {

for (Seminar seminar : trainer.getSeminars()) {

for (LocalDate available : availability) {

if (seminar.getStart().equals(available) &&

seminar.getAttendees().size() < 10) {

seminar.getAttendees().add(employee);

return available;

}

}

}

}

return null;

}

}

/**

* A trainer that runs in person seminars.

*/

public class Trainer {

private String name;

private String room;

private List<Seminar> seminars;

public List<Seminar> getSeminars() {

return seminars;

}

}

How and why does it violate this principle?

What other properties of this design are not desirable?

/**

* An online seminar is a video that can be viewed at any time by employees. A

* record is kept of which employees have watched the seminar.

*/

public class OnlineSeminar extends Seminar {

private String videoURL;

private List<String> watched;

}

/**

* An in person all day seminar with a maximum of 10 attendees.

*/

public class Seminar {

private LocalDate start;

private List<String> attendees;

public LocalDate getStart() {

return start;

}

/**

* Try to book this seminar if it occurs on one of the available days and

* isn't already full

* @param employee

* @param availability

* @return The date of the seminar if booking was successful, null otherwise

*/

public LocalDate book(String employee, List<LocalDate> availability) {

for (LocalDate available : availability) {

if (start.equals(available) &&

attendees.size() < 10) {

attendees.add(employee);

return available;

}

}

return null;

}

}

public class TrainingSystem {

public List<Trainer> trainers;

/**

* Try to booking training for an employee, given their availability.

*

* @param employee

* @param availability

* @return The date of their seminar if booking was successful, null there

* are no empty slots in seminars on the day they are available.

*/

public LocalDate bookTraining(String employee, List<LocalDate> availability) {

for (Trainer trainer : trainers) {

LocalDate booked = trainer.book(employee, availability);

if (booked != null)

return booked;

}

return null;

}

}

/**

* A trainer that runs in person seminars.

*/

public class Trainer {

private String name;

private String room;

private List<Seminar> seminars;

public List<Seminar> getSeminars() {

return seminars;

}

/**

* Try to book one of this trainer's seminars.

* @param employee

* @param availability

* @return The date of the seminar if booking was successful, null if the

* trainer has no free slots in seminars on the available days.

*/

public LocalDate book(String employee, List<LocalDate> availability) {

for (Seminar seminar : seminars) {

LocalDate booked = seminar.book(employee, availability);

if (booked != null)

return booked;

}

return null;

}

}TrainingSystemno longer has knowledge ofSeminar- Each class has their own responsibility (good cohesion)

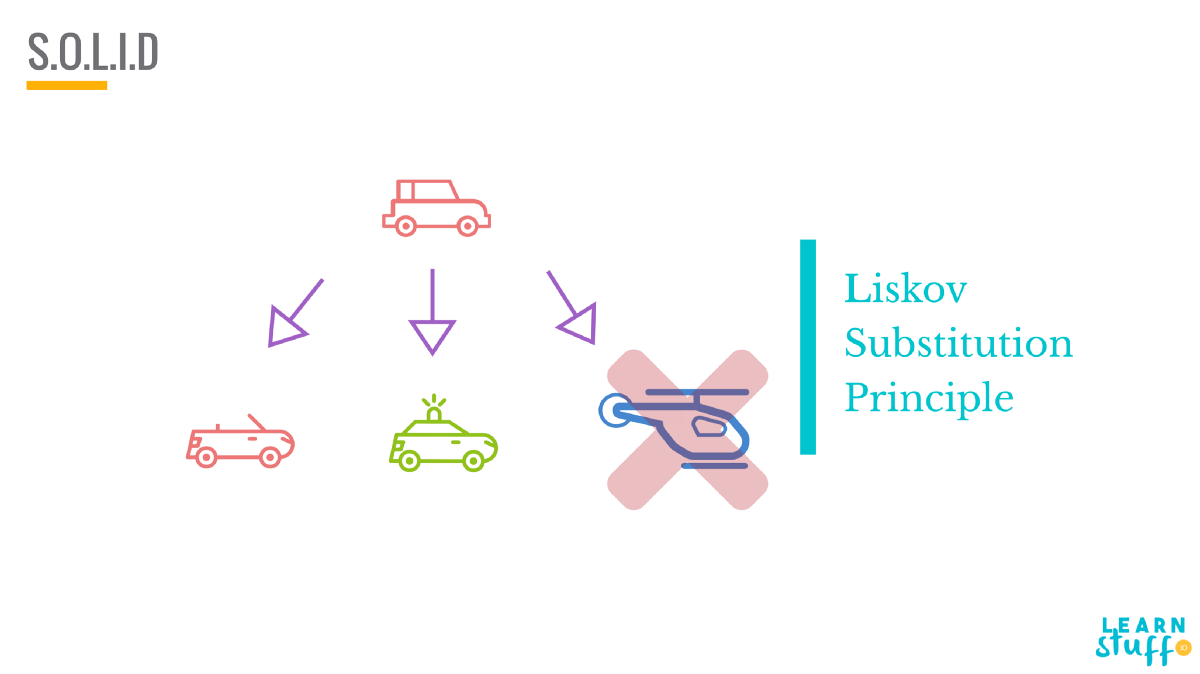

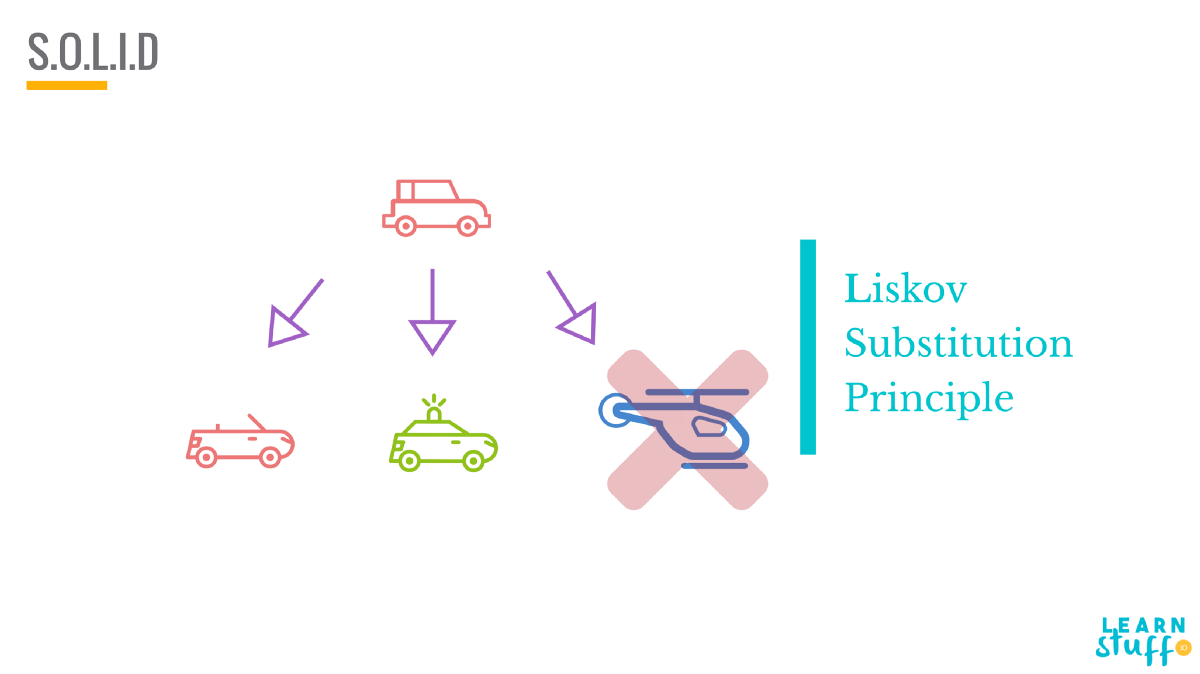

Liskov Substitution Principle

Liskov Substitution Principle

What is it?

Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) states that objects of a superclass should be replaceable with objects of its subclasses without breaking the application.

*inheritance arrows are the other way around

Liskov Substitution Principle

Solve the problem without inheritance

- Delegation - delegate the functionality to another class

- Composition - reuse behaviour using one or more classes with composition

Design principle: Favour composition over inheritance

If you favour composition over inheritance, your software will be more flexible, easier to maintain, extend.

Liskov Substitution Principle

/**

* An online seminar is a video that can be viewed at any time by employees. A

* record is kept of which employees have watched the seminar.

*/

public class OnlineSeminar extends Seminar {

private String videoURL;

private List<String> watched;

}

/**

* An in person all day seminar with a maximum of 10 attendees.

*/

public class Seminar {

private LocalDate start;

private List<String> attendees;

public LocalDate getStart() {

return start;

}

public List<String> getAttendees() {

return attendees;

}

}

Where does OnlineSeminar violate LSP?

OnlineSeminar doesn't require a list of attendees

Streams

Streams

Streams abstract away the details of data structures and allows you to access all the values in the data structure through a common interface

List<String> strings = new ArrayList<String>(Arrays.asList(new String[] {"1", "2", "3", "4", "5"}));

for (String string : strings) {

System.out.println(string);

}

List<String> strings = new ArrayList<String>(Arrays.asList(new String[] {"1", "2", "3", "4", "5"}));

strings.stream().forEach(x -> System.out.println(x));Map<String, Integer> map = new HashMap<>();

map.put("One", 1);

map.put("Two", 2);

map.put("Three", 3);

map.entrySet().stream().forEach(x -> System.out.printf("%s, %s\n", x.getKey(), x.getValue()));Streams

Common uses of streams are:

- forEach

- filter

- map

- reduce

Sort of similar to the Array prototypes/methods in JavaScript

Code Demo

Streams

Code Demo

Convert the following to use streams

package stream;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<String> strings = new ArrayList<String>(Arrays.asList(new String[] { "1", "2", "3", "4", "5" }));

for (String string : strings) {

System.out.println(string);

}

List<String> strings2 = new ArrayList<String>(Arrays.asList(new String[] { "1", "2", "3", "4", "5" }));

List<Integer> ints = new ArrayList<Integer>();

for (String string : strings2) {

ints.add(Integer.parseInt(string));

}

System.out.println(ints);

}

}package stream;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<String> strings = new ArrayList<String>(Arrays.asList(new String[] { "1", "2", "3", "4", "5" }));

// Same thing

strings.stream().forEach(x -> System.out.println(x));

// Use if there is more than one line of code needed in lambda

strings.stream().forEach(x -> {

System.out.println(x);

});

List<String> strings2 = new ArrayList<String>(Arrays.asList(new String[] { "1", "2", "3", "4", "5" }));

List<Integer> parsedStrings = strings2.stream().map(x -> Integer.parseInt(x)).collect(Collectors.toList());

strings2.stream().map(x -> Integer.parseInt(x)).forEach(x -> System.out.println(x));

}

}Design By Contract

Design By Contract

At the design time, responsibilities are clearly assigned to different software elements, clearly documented and enforced during the development and using unit testing and/or language support.

- Clear demarcation of responsibilities helps prevent redundant checks, resulting in simpler code and easier maintenance

- Crashes if the required conditions are not satisfied. May not be suitable for highly availability applications

Design By Contract

Every software element should define a specification (or a contract) that govern its transaction with the rest of the software components.

A contract should address the following 3 conditions:

- Pre-condition - what does the contract expect?

- Post-condition - what does that contract guarantee?

- Invariant - What does the contract maintain?

Design By Contract

public class Calculator {

public static Double add(Double a, Double b) {

return a + b;

}

public static Double subtract(Double a, Double b) {

return a - b;

}

public static Double multiply(Double a, Double b) {

return a * b;

}

public static Double divide(Double a, Double b) {

return a / b;

}

public static Double sin(Double angle) {

return Math.sin(angle);

}

public static Double cos(Double angle) {

return Math.cos(angle);

}

public static Double tan(Double angle) {

return Math.tan(angle);

}

}public class Calculator {

/**

* @preconditions a, b != null

* @postconditions a + b

*/

public static Double add(Double a, Double b) {

return a + b;

}

/**

* @preconditions a, b != null

* @postconditions a - b

*/

public static Double subtract(Double a, Double b) {

return a - b;

}

/**

* @preconditions a, b != null

* @postconditions a * b

*/

public static Double multiply(Double a, Double b) {

return a * b;

}

/**

* @preconditions a, b != null, b != 0

* @postconditions a / b

*/

public static Double divide(Double a, Double b) {

return a / b;

}

/**

* @preconditions angle != null

* @postconditions sin(angle)

*/

public static Double sin(Double angle) {

return Math.sin(angle);

}

/**

* @preconditions angle != null

* @postconditions cos(angle)

*/

public static Double cos(Double angle) {

return Math.cos(angle);

}

/**

* @preconditions angle != null, angle != Math.PI / 2

* @postconditions tan(angle)

*/

public static Double tan(Double angle) {

return Math.tan(angle);

}

}Liskov Substitution Principle

Precondition Weakening & Postcondition Strengthening

Liskov Substitution Principle

What is it?

Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) states that objects of a superclass should be replaceable with objects of its subclasses without breaking the application.

*inheritance arrows are the other way around

Precondition Weaking

- An implementation or redefinition (method overriding) of an inherited method must comply with the inherited contract for the method

- Preconditions may be weakened (relaxed) in a subclass, but it must comply with the inherited contract

- An implementation or redefinition may lesson the obligation of the client, but not increase it

from 0 <= theta <= 90 to 0 <= theta <= 180 is weakening

[0, 90] => [0, 180]

Why?

LSP. I should be able to use the subclass's implementation in place of my super class.

COMP2511 Week 4 24T2

By Christian Tolentino

COMP2511 Week 4 24T2

- 165