Montréal-Django

Introduction to Coding Principles, Unit Testing and Mocking in Django

https://slides.com/ctrlweb/django-3/live

Welcome

Daniel LeBlanc

CEO at ctrlweb

@danidou

https://ca.linkedin.com/in/dleblanc78

YulDev Organizer

Montréal-Django Organizer

daniel@ctrlweb.ca

Job Offers

Job Seekers

Tonight's Objectives

- Key principles

- The Tester's Mantra

- The methodologies

- Mocking

This is an

introductory

talk

Key Principles

“ The intelligent have plans; the wise have principles. ”

- Raheel Farooq

DRY

Don't Repeat Yourself

"Every piece of knowledge must have a single, unambiguous, authoritative representation within a system."

KISS

Keep it simple, stupid

"Most systems work best if they are kept simple rather than made complicated; therefore simplicity should be a key goal in design and unnecessary complexity should be avoided."

YAGNI

You aren't gonna need it

"Always implement things when you actually need them, never when you just foresee that you need them."

SOLID

- single responsibility

- open-closed

- Liskov substitution

- interface segregation

- dependency inversion

Single responsibility

A class should have only a single responsibility.

Single responsibility

class BlogPost(models.Model):

title = models.CharField(max_length=255)

body = models.TextField()

slug = models.SlugField()

author = models.ForeignKey(User, related_name='posts')

create_date = models.DateTimeField(auto_now_add=True)

modified_date = models.DateTimeField(auto_now=True)

publish_date = models.DateTimeField(null=True)

Traditional, "fat" model

Single responsibility

from .behaviors import Authorable, Permalinkable, Timestampable, Publishable

class BlogPost(Authorable, Permalinkable, Timestampable, Publishable, models.Model):

title = models.CharField(max_length=255)

body = models.TextField()Compositional model

Single responsibility

class Authorable(models.Model):

author = models.ForeignKey(User)

class Meta:

abstract = True

class Permalinkable(models.Model):

slug = models.SlugField()

class Meta:

abstract = True

class Publishable(models.Model):

publish_date = models.DateTimeField(null=True)

class Meta:

abstract = True

[...]Reusable behaviours

Open/closed

Software entities should be opened to extension, but closed to modification.

Open/closed

In dynamic languages (such as Python), this is done by leveraging duck typing

Open/closed

Example: "QuackFlap" problem

for x in range(1, 46):

if x % 3 == 0 and x % 5 == 0:

print("Quack! *Flap*")

elif x % 5 == 0:

print("Quack!")

elif x % 3 == 0:

print("*Flap*")

else:

print(x)

Open/closed

class QuackFlapFactory:

def create():

rules = [QuackFlapRule(), FlapRule(), QuackRule(), NormalRule()]

return QuackFlap(rules)

create = staticmethod(create)

class QuackFlap:

def __init__(self, rules):

self.rules = rules

def say(self, x):

for rule in self.rules:

if rule.is_handled(x):

return rule.say(x)

class Rule:

def is_handled(self, x):

pass

def say(self, x):

pass

Example: "QuackFlap" problem with OCP

Open/closed

class NormalRule(Rule):

def is_handled(self, x):

return True

def say(self, x):

return x

class QuackRule(Rule):

def is_handled(self, x):

return x % 3 == 0

def say(self, x):

return "Quack!"

class FlapRule(Rule):

def is_handled(self, x):

return x % 5 == 0

def say(self, x):

return "*Flap*"

Example: "QuackFlap" problem with OCP

Open/closed

class QuackFlapRule(Rule):

def is_handled(self, x):

return x % 5 == 0 and x % 3 == 0

def say(self, x):

return "Quack! *Flap*"

if __name__ == '__main__':

quack_flap = QuackFlapFactory.create()

for i in range(1, 46):

print(quack_flap.say(i))

Example: "QuackFlap" problem with OCP

Liskov substitution

Objects in a program should be replaceable with instances of their subtypes without altering the correctness of that program.

Liskov substitution

Bad Example

def can_quack(animal):

if isinstance(animal, Duck):

return True

elif isinstance(animal, Snake):

return False

else:

raise RuntimeError('Unknown animal!')

if __name__ == '__main__':

print(can_quack(Duck()))

print(can_quack(Snake()))

print(can_quack(Elephant()))Liskov substitution

Better Example

def can_quack(animal):

return animal.can_quack()

class Animal(object):

def can_quack(self):

pass

class Duck(Animal):

def can_quack(self):

return True

class Snake(Animal):

def can_quack(self):

return False

if __name__ == '__main__':

print(can_quack(Duck()))

print(snake.can_quack(Snake()))Interface Segregation

Many client-specific interfaces are better than one general-purpose interface

Interface Segregation

The good news is: with duck typing, this is implicit.

Dependency Inversion

One should depend upon Abstractions, and not upon concretions.

Dependency Inversion

Bad Example

class Airline:

def book(self, origin, destination, date):

pass

class FlightBooker:

def __init__(self, starting_point, destination):

self.airline = Airline()

self.origin = starting_point

self.destination = destination

def book_two_way(self, start_date, return_date):

# Note: the definition for Airline.book is Airline.book(from, to, date)

self.airline.book(self.origin, self.destination, start_date)

self.airline.book(self.destination, self.origin, return_date)

def book_one_way(self, date):

self.airline.book(self.origin, self.destination, date)

Dependency Inversion

Better Example

class FlightBooker:

def __init__(self, airline, origin, destination):

self.airline = airline

self.origin = origin

self.destination = destination

def book_two_way(self, start_date, return_date):

# Note: the definition for Airline.book is Airline.book(from, to, date)

self.airline.book(self.origin, self.destination, start_date)

self.airline.book(self.destination, self.origin, return_date)

def book_one_way(self, date):

self.airline.book(self.origin, self.destination, date)

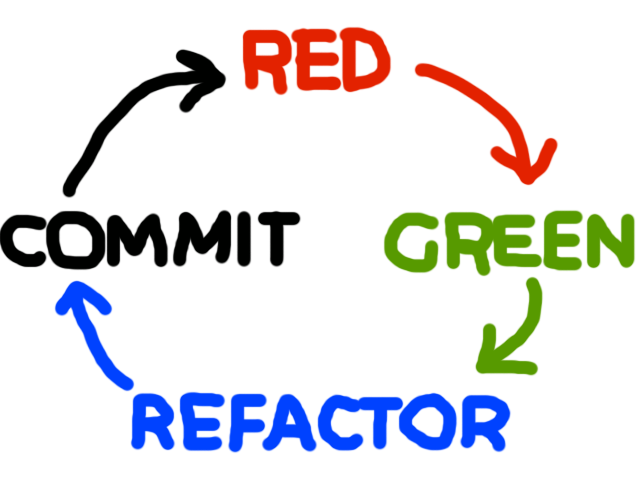

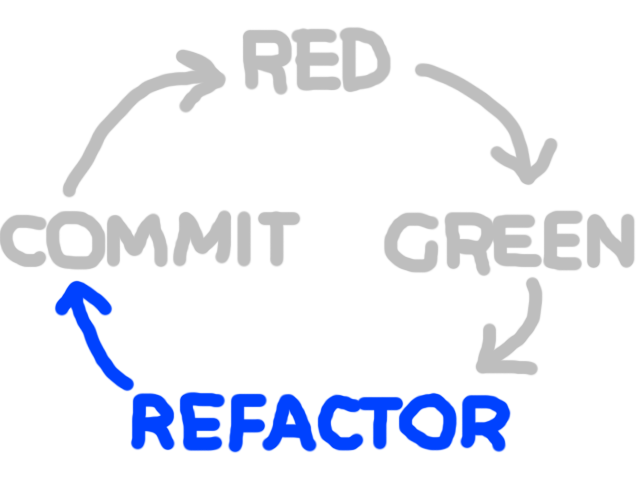

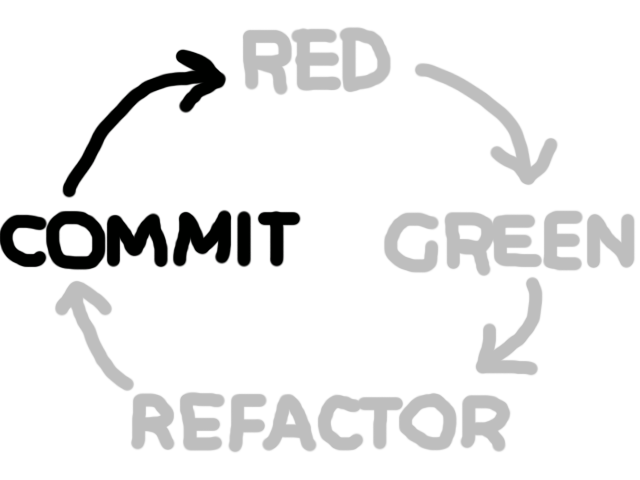

The Tester's Mantra

WRITE THE TEST

WRITE CODE WHICH

PASSES THE TEST

MAKE SURE ALL TESTS PASS &

REFACTOR SOME CODE

COMMIT CHANGES

Test Driven Development

(TDD)

“ Code without tests is broken as designed. ”

- Jacob Kaplan-Moss

What is it?

A software development process that relies on the repetition of a very short development cycle:

- write a unit test that defines a desired improvement or new function

- produce the minimum amount of code to pass that test

- refactor the new code to acceptable standards

- commit it

As a dev

- More robust code

- Simpler designs

- Breaks negative feedback loop

- Less time debugging

- Happiness

As a manager

- Compatible with agile project management

- Maintains a constant cost of change

- Happiness

Benefits

< DRY KISS!

< SOLID!

"Traditional" project

TDD/Agile project

As a dev

- Risk of "blind spots" in tests / code (unless peer reviewed)

- Doesn't fully cover functional tests (user interface, db, network, etc.)

As a manager

- Slower pace at the beginning

- Organizational support crucial to TDD application

- Quality of tests crucial to maintenance overhead costs

Cons

Six steps

- Add a test

- Run all tests and see if the new one fails

- Write some code

- Run test

- Refactor code

- Commit

(Rinse and repeat)

Step 1 - Add a test

from django.test import TestCase

from myapp.models import Animal

class AnimalTestCase(TestCase):

def setUp(self):

Animal.objects.create(name="lion", sound="roar")

Animal.objects.create(name="cat", sound="meow")

def test_animals_can_speak(self):

"""Animals that can speak are correctly identified"""

lion = Animal.objects.get(name="lion")

cat = Animal.objects.get(name="cat")

self.assertEqual(lion.speak(), 'The lion says "roar"')

self.assertEqual(cat.speak(), 'The cat says "meow"')< Creates test data

< Tests behaviours

Step 2 - Run all tests and see if the new one fails

$ ./manage.py test

Creating test database for alias 'default'...

E

======================================================================

ERROR: unittests.tests (unittest.loader._FailedTest)

----------------------------------------------------------------------

ImportError: Failed to import test module: unittests.tests

Traceback (most recent call last):

[...]

ImportError: cannot import name 'Animal'

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 0.000s

FAILED (errors=1)

Destroying test database for alias 'default'...

$ _Step 3 - Write some code

from django.db import models

class Animal(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=30)

sound = models.CharField(max_length=30)

def speak(self):

return 'The %s says "%s"' % (self.name, self.sound)Step 4 - Run test

$ ./manage.py test

Creating test database for alias 'default'...

.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 0.003s

OK

Destroying test database for alias 'default'...

Step 5 - Refactor code

from django.db import models

class Animal(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=30)

sound = models.CharField(max_length=30)

def speak(self):

return 'The %s says "%s"' % (self.name, self.sound)

def __unicode__(self):

return self.name

< WRONG! It's a new UNTESTED functionality!

In this case, the code isn't complex enough to require refactoring.

< YAGNI!

Git Flow

You are working in a feature branch. You can commit more than once per test cycle, but a pull request only when step 5 is completed.

Git

You are hopefully working in develop, or perhaps (gasp!) in master. In any case, don't commit until step 5 is completed.

Step 6 - Commit

Pro tip : USE GIT FLOW.

Behaviour Driven Development

(BDD)

“ Planning is everything. Plans are nothing.. ”

- Field Marshal Helmuth Graf von Moltke

What is it?

An extension of TDD which specifies that tests should be written in the form of user stories which describe the desired behaviour of the unit.

As a dev

- User stories are embedded in tests

- Implicitly improved understanding of user requirements

- More functional coverage

As a manager

- Compatible with agile project management

- Maintains a constant cost of change

- Greater business involvement

Benefits

As a dev

- Another library/tool to master

- More code to write

- Behaviour can be hard to describe in test format

As a manager

- Slower pace throughout the project

- Requires greater business involvment

Cons

Behave

Lettuce

A few frameworks

Salad

(Lettuce + Splinter)

Cucumber

(Ruby)

An example in Behave

Feature: Behave example

In order to play with Behave

As beginners

We'll test Google Search

Scenario: Find ctrlweb

Given I search for "ctrlweb"

Then the result page will include "CTRL+WEB"

Scenario: Find Montreal-Django

Given I search for "Montreal-Django"

Then the result page will include "Django Meetups"

tutorial.feature:

An example in Behave

from behave import *

from pytest import fail

from selenium.common.exceptions import NoSuchElementException

@given('I search for "{text}"')

def step_impl(context, text):

context.browser.get('https://www.google.ca/search?q='+text)

@then('the result page will include "{text}"')

def step_impl(context, text):

try:

context.browser.find_element_by_partial_link_text(text)

except NoSuchElementException:

fail('%r not in result page' % text)

pass

tutorial.py:

An example in Behave

from selenium import webdriver

def before_all(context):

context.browser = webdriver.Chrome()

def after_all(context):

context.browser.quit()

environment.py:

An example in Behave

$ behave

Feature: Behave example # tutorial.feature:1

In order to play with Behave

As beginners

We'll test Google Search

Scenario: Find ctrlweb # tutorial.feature:6

Given I search for "ctrlweb" # steps/tutorial.py:6 1.773s

Then the result page will include "CTRL+WEB" # steps/tutorial.py:11 0.067s

Scenario: Find Montreal-Django # tutorial.feature:10

Given I search for "Montreal-Django" # steps/tutorial.py:6 0.508s

Then the result page will include "Django Meetups" # steps/tutorial.py:11 0.397s

1 feature passed, 0 failed, 0 skipped

2 scenarios passed, 0 failed, 0 skipped

4 steps passed, 0 failed, 0 skipped, 0 undefined

Took 0m2.745s

$ _Domain-Driven Design

(DDD)

“ The heart of software is its ability to solve domain-related problems for its user. ”

- Eric Evans

What is it?

DDD is an approach to software development for complex needs by connecting the implementation to an evolving model. The premise of domain-driven design is the following:

- placing the focus on the core domain logic;

- basing complex designs on a model of the domain;

- initiating collaboration between technical and domain experts to iteratively refine a conceptual model that addresses particular domain problems.

To learn more about it:

Domain-Driven Design:

Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software

by Eric Evans

Mocking

What is it?

A mock is a simulated object which mimics the behaviour of a real object in a controlled way.

Versus stub / fake?

A fake is a class that implements an interface but contains fixed data and no logic.

A stub is like a mock class, but without the ability to verify that methods have been called or not called.

Restaurant example

Let's say you want to test a system in which a waiter takes an order from a client, gives it to the cook, receives food from the cook and gives it to the client.

Specifically, you want to test that the food made by the cook matches the order.

Restaurant example

A fake cook would pretend preparing food using tv dinners and a microwave.

A fake usually takes shortcuts in order to make its objects suitable for tests, but not for production.

Restaurant example

A stub cook would always prepare hot dogs no matter what the order.

A stub provide predefined answers to calls made during a test.

Restaurant example

A mock cook would be a cop pretending to be a cook in an undercover operation.

A mock is an object pre-programmed with specifications of the calls they are expected to receive.

Mock example

from django.test import TestCase

from unittest.mock import Mock

from django.utils import timezone

from .models import BlogPost

class BlogPostTestCase(TestCase):

def test_blog_post_is_published(self):

blogpost = Mock(spec=BlogPost)

blogpost.publish_date = timezone.now()

self.assertTrue(blogpost.is_published)

< Mock instance

< This will work

$ ./manage.py test mocking.tests

Creating test database for alias 'default'...

.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 0.001s

OK

Destroying test database for alias 'default'...

$ _Nice, but...

One of the main advantages of mocks is to allow speedy tests, without the need to write to database all the time.

This advantage is negated by the use of sqlite as a database engine for tests in Django, which will execute tests only in memory.

Recommandation

Don't use mocks.

Add this to your settings to use real data instead :

import sys

if 'test' in sys.argv or 'test_coverage' in sys.argv:

DATABASES['default'] = {'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.sqlite3'}References

Clean Coder - Robert C. Martin Domain-Driven Design - Eric Evans Django Model Behaviors - Kevin Stone Using Mocks in Python - José R.C. Cruz Mocking Django - Matthew J. Morrison

Merci!

Thank you!

Introduction to Unit Testing and Mocking in Django

By Daniel LeBlanc

Introduction to Unit Testing and Mocking in Django

Montréal Django #3

- 776