React JS

Introduction

Introduction to React JS

But before Starting,

Imagine this...

you open a webpage…

You click a button.

Something changes!

A message appears.

A cat picture loads.

The button turns green.

That’s not magic, it’s JavaScript talking to the browser!

But how does that work under the hood?

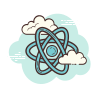

When your browser loads an HTML file, it doesn’t just display it, it builds a living, breathing structure behind the scenes called the DOM (Document Object Model).

Every <div>, <h1>, <button> becomes a room or object inside that house

And the best part? JavaScript can walk through this house and rearrange furniture anytime!

Think of it like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<title>Document</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello, World!</h1>

<h2>Welcome to my website</h2>

</body>

</html>Your HTML = blueprint

The DOM = actual house the browser builds from that blueprint

Example

<button id="toggleBtn">Show/Hide Secret</button>

<p id="secret">Shhh… I’m a secret! 🤫</p>const btn = document.getElementById("toggleBtn");

const msg = document.getElementById("secret");

btn.addEventListener("click", () => {

if (msg.style.display === "none") {

msg.style.display = "block";

} else {

msg.style.display = "none";

}

});Let’s say we want to hide a secret message when someone clicks a button. Here’s how we’d do it with plain JavaScript:

It works!

But… what if we have 10 secrets? 100 buttons? Suddenly we’re writing the same code over and over… and forgetting which element has which ID…

The Real Problem

As your app grows, DOM manipulation becomes fragile and hard to track. Why?

-

Too many moving parts: You update one element, but forget it affects another.

-

No single source of truth: Is the data in a variable? In the DOM? In localStorage?

-

Performance issues: Changing the DOM is slow, browsers weren’t built for constant updates

-

Readability nightmare: Your code looks like a bowl of callback spaghetti 🍝

You start spending more time fixing bugs than building features !

Imagine you’re building a shopping cart. Simple, right?

But now:

The user adds an item → you create a new <div>, set its text, attach an event listener, update the total

They remove an item → you find the right <li>, delete it, recalculate the total, check if the cart is empty

They change quantity → you parse the input, update price, maybe show a “Max 5 items!” warning

And it works… until:

⚠️ They click “Remove” twice → you try to delete an element that’s already gone → ERROR

⚠️ The total shows $24.98 instead of $24.99 → floating-point math + manual updates = 💥

⚠️ You need to sync the cart across tabs → now you’re wrestling with localStorage AND the DOM

- You’re not building a cart anymore—you’re debugging a house of cards.

const item = document.createElement("li");

item.innerText = name;

item.addEventListener("click", () => { ... });

cartList.appendChild(item);

totalPrice.innerText = "$" + (currentTotal + price);

// ...and 20 more lines like thisNow imagine a different world.

My cart contains these items:

T-shirt ($15.99) × 1

Mug ($8.50) × 2

So the UI should show those items and a total of $32.99.

That’s it.

React takes that list of items (your data) and builds the entire cart UI from scratch—every time.

It uses a Virtual DOM (a lightweight copy) to:

But don’t panic! It doesn’t actually rebuild the whole page.

1. Render the “new” cart in memory

2. Compare it with the “old” one

3. Update only the real DOM parts that changed (e.g., just the total number)

So you write less code, make fewer mistakes, and never wonder “Did I update the price?”

This is the power of thinking in React:

Instead of:

“Find the price element, parse its text, add the new item’s cost, round it, and set innerText…”

You just:

“Add the item to my list. The UI will reflect the truth.”

Your code becomes:

✅ Simpler (no DOM queries)

✅ More predictable (UI = function of data)

✅ Easier to reason about (one source of truth)

And when your app grows?

Adding a “Save for Later” section, a coupon code, or real-time inventory checks…

feels natural, not terrifying.

Because you’re not wrestling the DOM anymore.

You’re describing reality—and React makes the screen match it

So what is React—really?

It’s not a framework.

It’s not a language.

React is an open-source JavaScript library for building user interfaces by breaking them into reusable pieces called components.

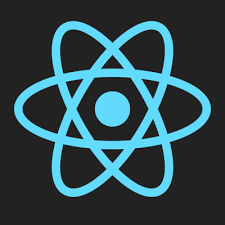

Analogie !

Think of React as a LEGO set for building UIs: you create small, reusable pieces (components) and snap them together to build something amazing.

But more importantly:

React handles the DOM updates for you, so you can focus on what your app should do, not how to poke the browser.

And it’s smart: it only updates the parts of the page that actually changed (thanks to the Virtual DOM).

Why Use React JS

Key Features & Benefits

&

Code Reusability

const UserCard = ({ user }) => {

return (

<div className="user-card">

<img src={user.avatar} alt={user.name} className="avatar" />

<div className="user-details">

<h2>{user.name}</h2>

<p>Email: {user.email}</p>

</div>

</div>

);

};

Efficiency and Performance

Virtual DOM

Efficiently updates only necessary parts of the UI

Components

Everything in React is a component!

Modular building blocks for UI

Vibrant Community

- Large developer community

- Abundance of open-source libraries

Popularity

Widely adopted by major companies and developers worldwide

Dev

Environement

Before we write a single line of React code…

we need a workspace where:

- Our fancy modern JavaScript works in every browser

- We can split code into neat files (not one giant script!)

- We can use new react features (like JSX, import, etc.)

But browsers? They’re… kinda old-school.

They don’t understand import React from 'react'

So we need a secret translator + organizer.

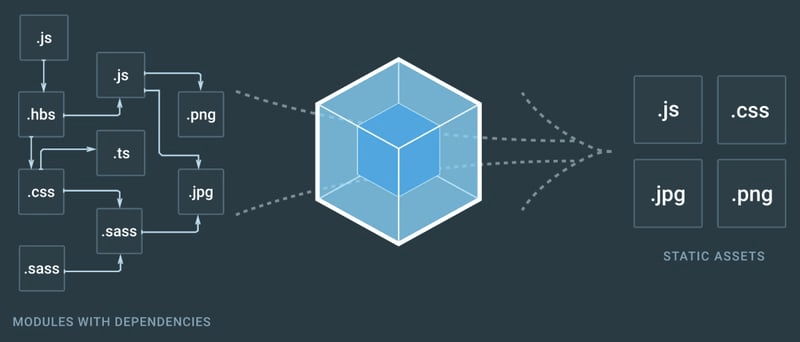

What are bundlers ?

A bundler does 3 things:

- Combines all your files into one (or few) files browsers can load.

- Transpiles modern JS/JSX into older JS that even Internet Explorer (RIP) could almost understand.

- Optimizes everything (minify, compress, cache) so your app loads fast.

Popular bundlers for React

CRA

Create React App is the traditional way to create single-page React applications. It sets up a new React project with a pre-configured build setup using webpack and Babel.

Vite

Vite is a next-generation build tool for frontend development. It focuses on speed and efficiency by leveraging ES Module imports and server-side rendering (SSR) capabilities.

But wait, how does Vite convert your code so fast?

SWC excels in performance and modern JavaScript/TypeScript support, making it ideal for projects that require fast compilation times and support for the latest ECMAScript features.

SWC

Babel, while slightly slower in compilation speed compared to SWC, offers unparalleled flexibility, extensive plugin support, and broad compatibility across different JavaScript environments and syntax versions.

Babel

Creating a new React project using Vite

1. Open your terminal and type:

npm create vite@latest 2. Select your project settings

3. run your app

cd app-name

npm install

npm run devYour app is live at http://localhost:5173 (or similar), and it hot-reloads (changes appear instantly as you code)!

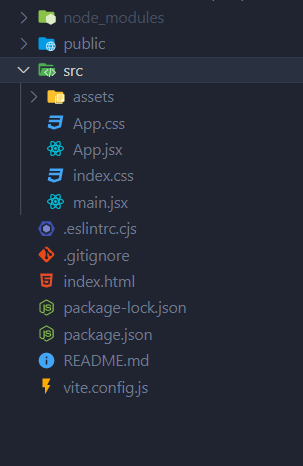

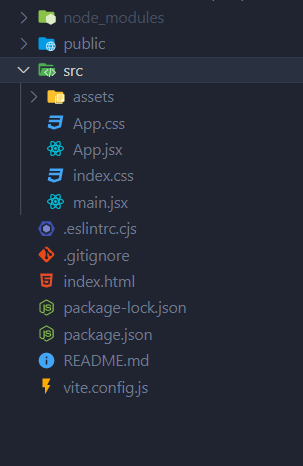

Understanding the project structure

Understanding the project structure

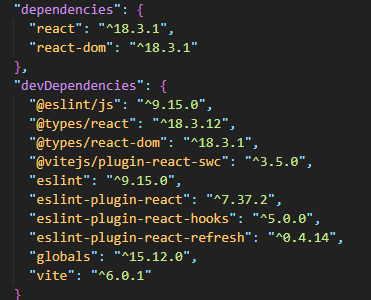

Managing project dependencies with npm

Creating and using components in React

TS Compiler

configuration

How to configure TS

-

tsconfig.json is a configuration file for TypeScript projects.

-

It specifies the root files and the compiler options required to compile the project.

-

Basic Structure of '

tsconfig.json'

{

"compilerOptions": {

// Compiler options go here

},

"include": [

// List of files to include

],

"exclude": [

// List of files to exclude

]

}Key Compiler Options

- module: Specifies the module system t for the compiled code.

"module": "commonjs"- strict: Enables all strict type-checking options

"strict": true- jsx: Specifies how JSX should be compiled.

"jsx": "react"- target: Specifies the target JS version for the compiled output.

"target": "es6"Important Compiler Options

- moduleResolution: Determines how modules are resolved.

"moduleResolution": "node"- esModuleInterop: Enables compatibility with CommonJS modules.

"esModuleInterop": true-

skipLibCheck: Skips type checking of declaration files

(.d.ts).

"skipLibCheck": true-

forceConsistentCasingInFileNames: Prevents case-sensitive import mismatches.

"forceConsistentCasingInFileNames": trueImportant Compiler Options

-

rootDir: Specifies the source directory containing TypeScript files.

"rootDir": "./src"-

outDir: Defines the output directory for compiled.jsfiles.

"outDir": "./dist"-

noEmitOnError: Prevents TypeScript from generating.jsfiles if there are compilation errors.

"noEmitOnError": trueExample tsconfig.json

{

"compilerOptions": {

"target": "es6", // Compile to ES6 JavaScript

"module": "commonjs", // Use CommonJS modules

"strict": true, // Enable all strict type-checking options

"jsx": "react", // Support React JSX

"moduleResolution": "node", // Use Node.js-style module resolution

"esModuleInterop": true, // Enable ES module interoperability

"skipLibCheck": true, // Skip type-checking of declaration files

"forceConsistentCasingInFileNames": true, // Ensure consistent file casing

"outDir": "./dist", // Output directory for compiled files

"rootDir": "./src" // Root directory for source files

},

"include": ["src/**/*"], // Include all files in the src directory

"exclude": ["node_modules", "dist"] // Exclude node_modules and dist directories

}How to go from JS to TS

Basic TypeScript Syntax

Types and Type Annotations

Javascript

- number

- string

- boolean

- null

- undefined

- object

Typescript

- any

- unknown

- never

- enum

- tuple

- generics

let age: number = 30;

let name: string = "Fatima";

let isStudent: boolean = false;The any Type

The any type in TypeScript allows a variable to hold values of any type. It effectively disables TypeScript’s type checking, making it similar to regular JavaScript.

let data: any = "Hello";

data = 42; // No error, but could lead to bugs

function render(document: any) {

console.log(document)

}Here, data can be reassigned to any value without restrictions.

Using any removes TypeScript's benefits, such as type safety and autocompletion. It can lead to runtime errors and make debugging harder.

The unknown Type

The unknown type is a safer alternative to any, as it restricts how the value can be used. It represents a value that is not known at compile time.

let data: unknown;

data = "Hello";

data = 42;

data = true;

As a best practice, avoid unknown unless absolutely necessary, and prefer explicitly typed variables for better type safety!

Advanced TypeScript Features

Functions in TypeScript

TypeScript allows us to define function parameters and return types to ensure type safety and catch errors early.

function greet(name: string, age?: number): string {

return age ? `Hello, ${name}, you are ${age} years old.` : `Hello, ${name}!`;

}

console.log(greet("Alice")); // ✅ "Hello, Alice!"

console.log(greet("Bob", 25)); // ✅ "Hello, Bob, you are 25 years old."

Enums in TypeScript

Enums (Enumerations) in TypeScript allow you to define a set of named constants

enum Status {

Pending, // 0

InProgress, // 1

Completed // 2

}

let taskStatus: Status = Status.InProgress;

console.log(taskStatus); // Output: 1enum Role {

User = 1,

Admin = 5,

SuperAdmin = 10

}

console.log(Role.Admin); // Output: 5Tuples in TypeScript

A tuple in TypeScript is a fixed-length array where each element has a specific type. Unlike regular arrays, tuples enforce strict type positioning.

let user: [string, number] = ["Alice", 25]; - Enforces a fixed structure with specific types.

- Useful for returning multiple values with known positions (e.g.,

[status, message]).

Objects in TypeScript

In TypeScript, objects can have strict type definitions to ensure their structure remains consistent.

let user: {id: number; name: string; email: string } = {

id: 1,

name: "Fatima",

age: "test@gmail.com"

};

Interfaces and Type Aliases

interface User {

id: number;

name: string;

email: string;

}

type Employee = {

name: string;

position: string;

};

type ID = number | string;

So far, we've seen how TypeScript allows us to define object types explicitly. However, as our code grows, repeating object structures can become inefficient and hard to maintain

When to Use Type vs Interface

Type

type ID = string | number;

type Coordinates = [number, number];

type Status = "active" | "inactive";- Use for creating primive types.

- Use for creating union types.

- Use for creating tuples.

- Use for creating intersections.

When to Use Type vs Interface

Interface

type ID = string | number;

type Coordinates = [number, number];

type Status = "active" | "inactive";

interface Animal {

name: string;

}

interface Dog extends Animal {

breed: string;

}- Use for defining object structures (shapes).

- Preferred for extending (inheritance).

Exercice

const product = {

name: "Shampoo",

price: 2.99,

images: ["image-1.png", "image-2.png"],

status: "published",

};

- create a type describing this object

- use an enum for the "status" field

From Objects to Generics

So far, we've defined types explicitly for functions, objects, and arrays. But what if we need a flexible way to handle multiple types while maintaining type safety?

This is where Generics come in ✨

Generics

- Generics allow us to write reusable and type-safe code without specifying exact types upfront.

- They enable us to create components, functions, and data structures that work with different types dynamically.

-

Why use generics

- Avoid code duplication by making functions & components flexible.

- Maintain type safety without sacrificing reusability.

- Work with any data type while still enforcing constraints.

Generic Functions

Without Generics (Bad Practice)

function identity(value: any): any {

return value;

}

const result = identity(42); // No type safety 😬

With Generics (Best Practice)

function identity<T>(value: T): T {

return value;

}

const num = identity(42); // num is inferred as number

const text = identity("Hello"); // text is inferred as string

Problem: We lose type safety because any can be anything.

-

<T>represents a generic type. - TypeScript infers the type automatically!

Generic Constraints

Sometimes, we want to restrict the types that can be used.

interface HasLength {

length: number;

}

function logLength<T extends HasLength>(value: T): void {

console.log(`Length: ${value.length}`);

}

logLength("Hello"); // ✅ Works (string has length)

logLength([1, 2, 3]); // ✅ Works (array has length)

// logLength(42); ❌ Error (number has no length)

T extends HasLength restricts T to only types with a .length property.

Utility Types

Partial<T>

interface User {

id: number;

name: string;

age: number;

}

type PartialUser = Partial<User>;

// PartialUser is { id?: number; name?: string; age?: number; }Omit<T, K>

type UserWithoutEmail = Omit<User, 'email'>;

// UserWithoutAge is { id: number; name: string; }Pick<T, K>

type UserName = Pick<User, 'name'>;

// UserName is { name: string; }- Makes all properties in a type optional.

- Removes specific properties from a type.

- Picks specific properties from a type.

TypeScript with React

Setting Up a TypeScript + Vite React Project

Installing Vite with TypeScript

npm create vite@latest Navigate to the project and install dependencies

cd my-react-app

npm installVite automatically generates a tsconfig.json file.

Typing Props

interface UserProps {

name: string;

age: number;

isActive?: boolean; // Optional prop

}

const User = ({ name, age, isActive = true }: UserProps) => {

return (

<div>

<p>Name: {name}</p>

<p>Age: {age}</p>

<p>Status: {isActive ? "Active" : "Inactive"}</p>

</div>

);

};type ButtonProps = {

label: string;

onClick: () => void;

};

const Button: React.FC<ButtonProps> = ({ label, onClick }) => {

return <button onClick={onClick}>{label}</button>;

};Typing Hooks

useState

const [count, setCount] = React.useState<number>(0);

const [user, setUser] = React.useState<User | null>(null);useReducer

type Action = { type: "INCREMENT" } | { type: "DECREMENT" };

const counterReducer = (state: number, action: Action): number => {

switch (action.type) {

case "INCREMENT":

return state + 1;

case "DECREMENT":

return state - 1;

default:

return state;

}

};- explicitly defining the state type helps prevent errors

- Reducers benefit from strong TS typing

useEffect

- doesn’t require explicit typing

Typing Events

Input Events

const InputField: React.FC = () => {

const [value, setValue] = useState<string>("");

const handleChange = (event: React.ChangeEvent<HTMLInputElement>) => {

setValue(event.target.value);

};

return <input type="text" value={value} onChange={handleChange} />;

};Click Events

const Button: React.FC = () => {

const handleClick = (event: React.MouseEvent<HTMLButtonElement>) => {

console.log("Button clicked!");

};

return <button onClick={handleClick}>Click Me</button>;

};Typing API Calls (Fetching Data)

Typing API Responses

type User = {

id: number;

name: string;

email: string;

};

const fetchUsers = async (): Promise<User[]> => {

const response = await fetch("https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users");

return response.json();

};Using TypeScript with API calls ensures correct data handling

React introduction

By Fatima BENAZZOU

React introduction

- 35