Advanced features and Sofware Craft

SHODO

Hello! I'm Nathan.

- Co-founder of Shodo Lille

- Backend developer

- Pushing Go to production since 2014

- Worked 10 years at OVHcloud

- Inclusion & Diversity activist

- https://bento.me/nathan-castelein

What about you?

The next four hours

Welcome to the "Advanced features and Software Craft" training

This presentation is in English. Many terms do not have a proper translation in French.

This is my early stages as Go trainer. If you have any question at any time, feel free to ask.

Schedule

Morning session

- 9h: Session start

- 10h: 5 minutes break

- 11h: 10 minutes break

- 12h: 5 minutes break

- 13h: Session ends

Afternoon session

- 14h: Session start

- 15h: 5 minutes break

- 16h: 10 minutes break

- 17h: 5 minutes break

- 18h: Session ends

What do you expect

from this training?

Content

- Generics

- Interfaces

- Software Craft & Code Design

- (bonus) Concurrency

A four-hours training means ...

- A lot of resources will be provided to go further outside of the training session

- Some topics are excluded from this training session

- Sometimes, it's my point of view

- I'm available for any question following the session: nathan.castelein@shodo-lille.io

Prerequisites

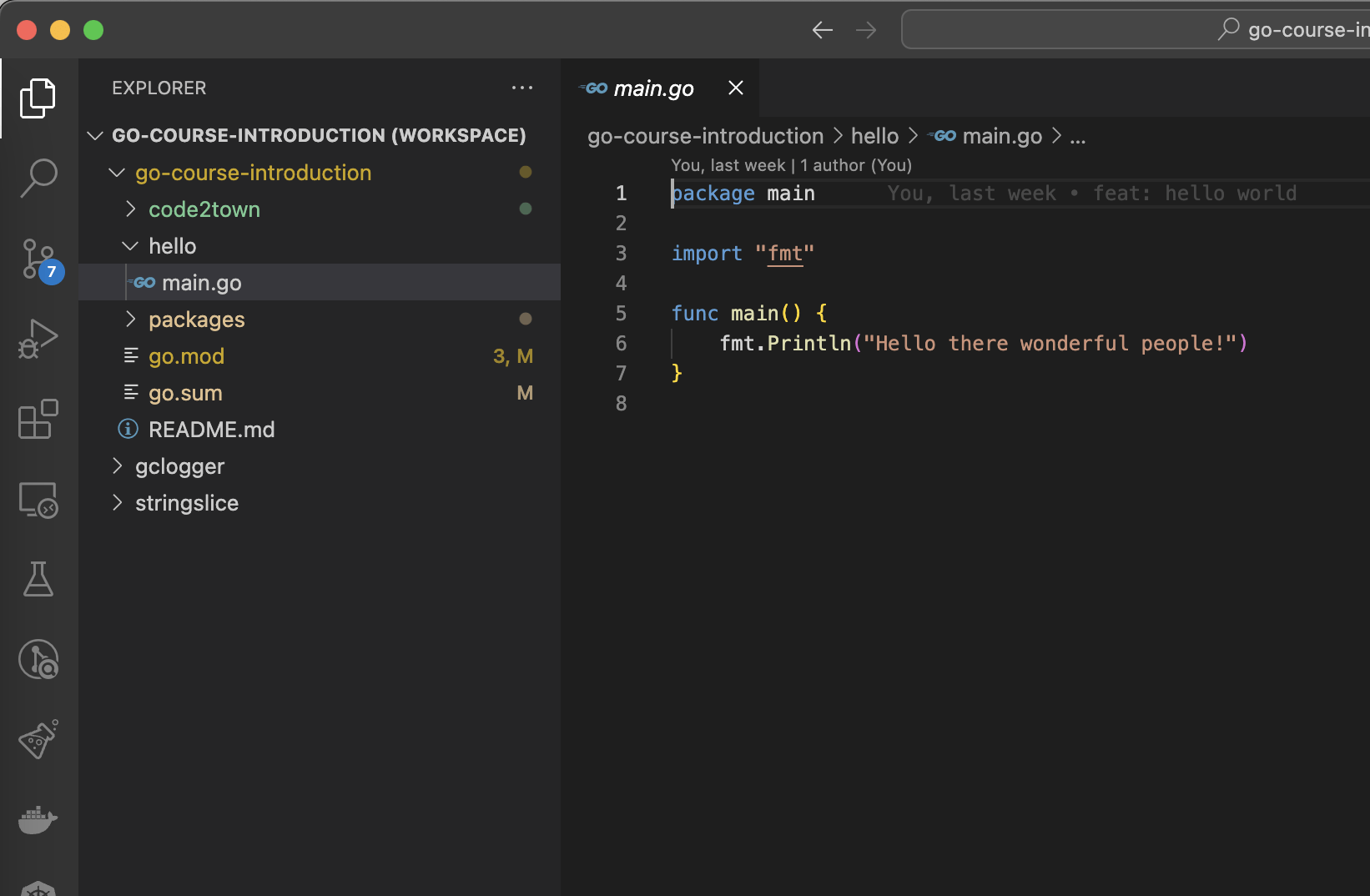

- Go v1.22

- Visual Studio Code

- Git

Generics

Generics

Also known as parametric polymorphism, this concept allows a single piece of code to be given a "generic" type, using variables in place of actual types, and then instantiated with particular types as needed.

It forms the basis of generic programming.

Let's start with a simple exercise

Let's refresh our memory by writing simple functions and unit tests!

File to open:

generics/exercise1.mdA simple example

func ContainsString(slice []string, elem string) bool {

for _, sliceElem := range slice {

if sliceElem == elem {

return true

}

}

return false

}

func ContainsInt(slice []int, elem int) bool {

for _, sliceElem := range slice {

if sliceElem == elem {

return true

}

}

return false

}A bit redundant, isn't it?

Introducing Generics in Go

func Count[T comparable](slice []T, elem T) int {

count := 0

for _, sliceElem := range slice {

if sliceElem == elem {

count++

}

}

return count

}Since Go 1.18, generics have been integrated the language.

Focus on function signature

func Count

[T

comparable]

(slice []T,

elem T)

int {

}Let's have a focus on function signature

Type constraints

Type constraints in generics are interfaces required to be matched by the types.

It defines an expected behaviour for the types, so we can perform actions on it. Typical used constraints:

- any

- comparable

- constraints.Ordered

- basic types: int, float, complex, etc.

- interface

Type constraints

func Sum[T int64 | float64](slice []T) T {

var total T

for _, element := range slice {

total += element

}

return total

}You can create an union of multiple constraints using the pipe "|" char.

Write your first generic function

Let's use generics to rewrite our function!

File to open:

generics/exercise1.mdWrite your first generic function

func Contains[T comparable](slice []T, elem T) bool {

for _, sliceElem := range slice {

if sliceElem == elem {

return true

}

}

return false

}

func ContainsMap[K, V comparable](m map[K]V, elem V) bool {

for _, mapElem := range m {

if mapElem == elem {

return true

}

}

return false

}Generics in struct declaration

Generics can be used in function declaration, but they can also be used for structs.

We can easily extend data structures with new helpers functions: an ordered map, a queue, a list, etc.

Let's have an example with maps.

Generics in struct

type Map[Key comparable, Value any] struct {

store map[Key]Value

}

func NewMap[Key comparable, Value any]() *Map[Key, Value] {

return &Map[Key, Value]{

store: map[Key]Value{},

}

}Generics in struct

func (m Map[Key, Value]) Keys() []Key {

keys := make([]Key, len(m.store))

var i int

for key := range m.store {

keys[i] = key

i++

}

return keys

}

func (m *Map[Key, Value]) Store(key Key, value Value) {

m.store[key] = value

}Generics in struct

func TestMapKeys(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

m := NewMap[string, int]()

m.Store("hello", 1)

m.Store("world", 2)

// Act

keys := m.Keys()

// Assert

require.Len(t, keys, 2)

require.Equal(t, []string{"hello", "world"}, keys)

}A generic queue?

A Queue has been implemented!

But it works only with int, it's a shame isn't it?

Let's rewrite a bit with generics!

File to open:

generics/exercise2.mdA generic queue

type Queue[T any] struct {

elements []T

}

func (f *Queue[T]) Push(element T) {

f.elements = append(f.elements, element)

}

func (f *Queue[T]) Pop() (T, error) {

if len(f.elements) == 0 {

var zeroValue T

return zeroValue, errors.New("no more elements")

}

element, newSlice := f.elements[0], f.elements[1:]

f.elements = newSlice

return element, nil

}When to use generics?

If you find yourself writing the exact same code multiple times, where the only difference is that the code uses different types, you can use a generic type parameter.

Avoid type parameters until you notice that you are about to write the exact same code multiple times.

Tips:

- Generics are good with data structures

- Start by writing code, not generics

- Rewrite with generics if needed, not by design

Generics example

You have many examples of Generics in this library: https://github.com/samber/lo?tab=readme-ov-file#-spec

Consider reading this library and reimplementing some stuffs for your needs!

Interfaces

Interfaces

An interface type is defined as a set of method signatures.

A value of interface type can hold any value that implements those methods.

Interfaces

Interfaces are one of the strongest feature of the language.

Interfaces are implemented implicitly. If your struct implements the proper methods, then the interface is satisfied and your type can be used as the interface.

If a function or a method requires an interface to work with, then you can easily write your own implementation.

Known interfaces

Example

type Speaker interface {

Speak() string

}

type Cat struct{}

func (c Cat) Speak() string {

return "Meow!"

}

type Dog struct{}

func (d Dog) Speak() string {

return "Wouf!"

}Example

func MakeSomeNoise(animals []Speaker) {

for _, animal := range animals {

fmt.Println(animal.Speak())

}

}

// in _test.go

func TestMakeSomeNoise(t *testing.T) {

// ...

// Act

MakeSomeNoise([]Speaker{

Cat{},

Dog{},

Cat{},

})

// Will print "Meow!", "Wouf!", "Meow!"

}A store of compute and storage

You're now owner of some code of an online store which sells compute and storage.

There's a code smell in the code: looks like it can be refreshed with an interface!

File to open:

interfaces/store/exercise1.mdA store of compute and storage

type Compute struct {

NumberOfVCPUs int

}

func (c Compute) GetPrice() float64 {

unitPrice := 3.0

return float64(c.NumberOfVCPUs) * unitPrice

}type Storage struct {

QuantityInGB float64

}

func (s Storage) GetPrice() float64 {

var unitPrice float64

switch {

case s.QuantityInGB >= 1024*10:

unitPrice = 1.0

case s.QuantityInGB >= 1024:

unitPrice = 1.5

default:

unitPrice = 2.0

}

return unitPrice * s.QuantityInGB

}type Pricer interface {

GetPrice() float64

}A store of compute and storage

type Basket struct {

Products []Pricer

}

func (b Basket) GetTotalPrice() float64 {

totalPrice := 0.0

for _, product := range b.Products {

totalPrice += product.GetPrice()

}

return totalPrice

}

func (b *Basket) AddProduct(product Pricer) {

b.Products = append(b.Products, product)

}Check if your structure matches a specific interface

var (

_ Pricer = &Storage{}

)

var (

_ Pricer = &Compute{}

)To confirm your structure properly implements a given interface, you can add a simple snippet into your code. This will help to detect any issue on interface implementation in your package.

A store of compute and storage

Unit tests

func TestGetTotalPrice(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

compute := Compute{NumberOfVCPUs: 4} // total price is 12

storage := Storage{QuantityInGB: 2000} // total price is 3000

basket := Basket{Products: []Pricer{compute, storage}}

expectedTotalPrice := 3012.0

// Act

totalPrice := basket.GetTotalPrice()

// Assert

if expectedTotalPrice != totalPrice {

t.Fatalf("expected total price %.2f, got %.2f", expectedTotalPrice, totalPrice)

}

}Something wrong with this test?

Testing Basket structure

For now, if you change the business rule to get the price of storage for example, then you have to modify the unit test of your Basket's GetTotalPrice method.

I'd not recommend to have this kind of design! Let's write a custom Pricer for our unit tests.

File to open:

interfaces/store/exercise2.mdTesting Basket structure

type StubPricer struct{}

func (StubPricer) GetPrice() float64 {

return 1.0

}

func TestGetTotalPriceWithStub(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

basket := Basket{Products: []Pricer{StubPricer{}, StubPricer{}, StubPricer{}, StubPricer{}}}

expectedTotalPrice := 4.0

// Act

totalPrice := basket.GetTotalPrice()

// Assert

if expectedTotalPrice != totalPrice {

t.Fatalf("expected total price %.2f, got %.2f", expectedTotalPrice, totalPrice)

}

}Interfaces in unit tests

Interfaces, when wisely used, can be a strong feature to keep your unit tests independent and properly scoped.

For this exercise, we just created a stub pricer, following the Test Double pattern we discussed in the previous module about tests (https://martinfowler.com/bliki/TestDouble.html).

It gives us a full control of the object's behaviour, so we test only the algorithm of GetTotalPrice.

To go this way, remind that you need to create unit tests for Compute and Storage structure!

Interface composition

type ReadWriter interface {

Reader

Writer

}An interface can be composed of ... an addition of other interfaces!

If you want to meet the ReadWriter interface, you need to meet the interface of Reader, and Writer.

Interfaces mindset

Interfaces should not embed an infinite list of methods. Prefer small interfaces and a bit of composed interfaces. Prefer naming interfaces for their behaviour, not by entity!

The bigger the interface, the weaker the abstraction.

Rob Pike

Clients should not be forced to depend on methods they do not use.

Robert C. Martin

Software Craft and code design

Software Craft?

The path to write good code

Let's start with Agile

What's Agile Software Development?

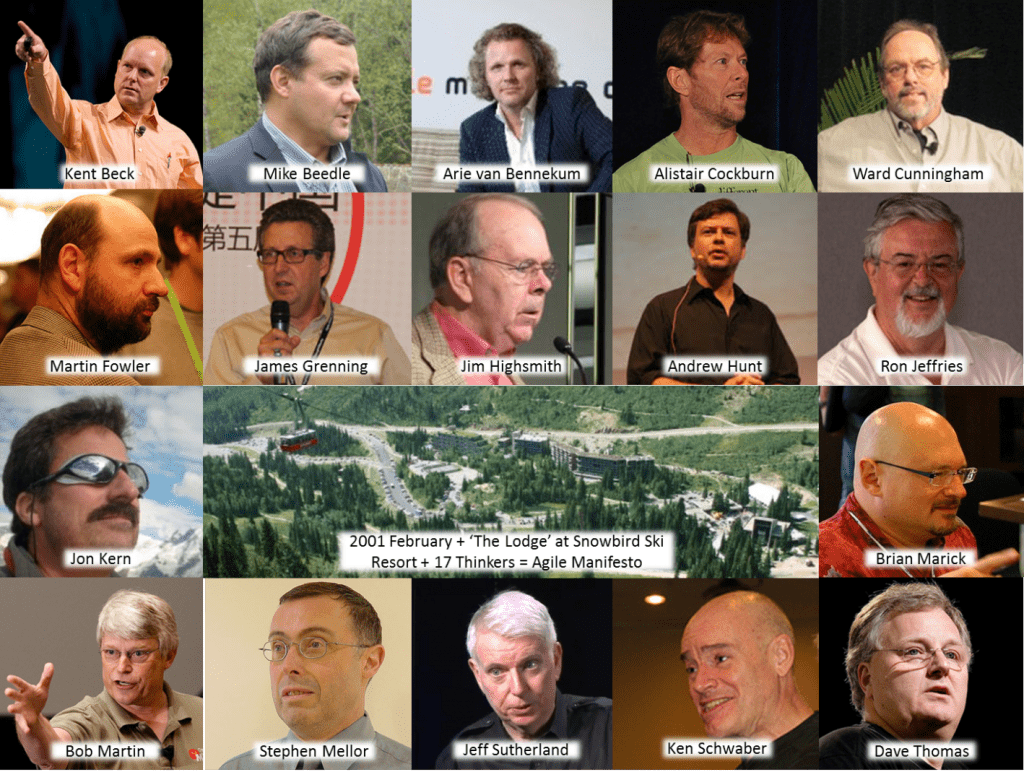

Agile in 2001

The Agile Software Development concept has been written down by 17 software developers in February 2001.

They created the Agile Manifesto.

Agile Manifesto

We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it. Through this work we have come to value:

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

Working software over comprehensive documentation

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Responding to change over following a plan

That is, while there is value in the items on

the right, we value the items on the left more.

And?

And that's all!

Scrum, Kanban, SAFE, etc. are just (good or bad) ways to achieve this goal. They're not agility, they're just tools!

You can have a look on this keynote by Alexandre Boutin: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wbr-eceBvto

And Software Craftsmanship?

Almost ten years after the Agile Manifesto, a group around Bob Martin wrote an extension to it: the Software Craftsmanship Manifesto (ie. Software Craft).

This document has been based on the work of various people who worked on software design and quality since many years (with books like Pragmatic Programmers in 1999, Software Craftsmanship in 2001, etc.).

Software Craft Manifesto

As aspiring Software Craftsmen we are raising the bar of professional software development by practicing it and helping others learn the craft. Through this work we have come to value:

Not only working software, but also well-crafted software

Not only responding to change, but also steadily adding value

Not only individuals and interactions, but also a community of professionals

Not only customer collaboration, but also productive partnerships

That is, in pursuit of the items on the left we have found the items on the right to be indispensable.

Software Craft

Software craft is the idea of pushing back the developer in the center of Software Development.

It is a response by software developers to the perceived ills of the mainstream software industry, including the prioritization of financial concerns over developer accountability.

A toolbox

Following this guide, Software Craft can be seen as a toolbox of practices, designs, ways of working together and self-improvement.

For example: TDD, BDD, DDD, Clean Architecture, Hexagonal Architecture, SOLID principles, Example Mapping, Event Storming, Pair Programming, Mob Programming/Software Teaming, etc.

Software Craft covers much more than writing code.

Software Craft in a Go training?

Regarding this training, we will mainly focus on some important design patterns we can use with Go.

It's a small part of Software Craft, but I hope I'll create some curiosity about those practices!

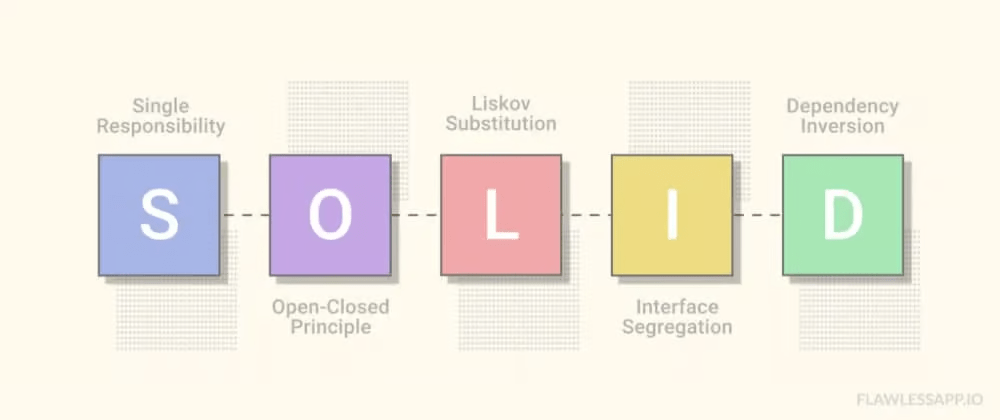

SOLID principles

SOLID principles

Designed by Robert C. Martin in the early 2000's, SOLID groups five design principles intended to make object-oriented designs more understandable, flexible, and maintainable.

It is an acronym!

Thanks to interfaces, it's easy to follow those principles.

SOLID Principles

Signs of bad code we want to get rid of with SOLID principles:

- Rigidity: Code to be difficult to change even if the change is small

- Fragility: Code to break whenever a new change is introduced in the system

- Immobility: Code being not reusable

- Viscosity: Hacking rather than finding a solution that preserve the design when it comes to change

Single-responsibility principle

type User struct {

FirstName string

LastName string

Email string

}

func (u *User) ChangeEmail(newEmail string) {

u.Email = newEmail

}

func (u *User) GetFullName() string {

return u.FirstName + " " + u.LastName

}

func (u *User) Save() error {

// Save user to the database

}Single-responsibility principle

type UserRepository struct {

db *sql.DB

}

func (u *UserRepository) Save(user User) error {

// Save user to the database

}There should never be more than one reason for a class to change. In other words, every class should have only one responsibility.

Do one thing, and do it well.

type User struct {

FirstName string

LastName string

Email string

}

func (u *User) ChangeEmail(newEmail string) {

u.Email = newEmail

}

func (u *User) GetFullName() string {

return u.FirstName + " " + u.LastName

}Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

type PaymentMethod struct {

Type string

}

func MakePayment(paymentMethod PaymentMethod) {

switch paymentMethod.Type {

case "CreditCard":

// Pay by credit card

case "PayPal":

// Pay by PayPal

...

}

}Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

type Payer interface {

Pay()

}

func MakePayment(paymentMethod Payer) {

paymentMethod.Pay()

}

type CreditCard struct {}

func (c *CreditCard) Pay() {

...

}

type PayPal struct {}

func (p *PayPal) Pay() {

...

}Software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification.

Liskov substitution principle (LSP)

type Swimmer interface {

Swim() string

}

type Shark struct{}

func (*Shark) Swim() string {

return "Shark is swimming."

}

func PoolParty(s Swimmer) string {

return s.Swim()

}In an object-oriented class-based language, the concept of the Liskov substitution principle is that a user of a base class should be able to function properly of all derived classes.

Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

type Bird interface {

Fly() string

Sing() string

}

type Pigeon struct{}

func (p *Pigeon) Fly() string {

return "Pigeon is flying."

}

func (p *Pigeon) Sing() string {

return "Pigeon is singing."

}

type Penguin struct{}

func (p *Penguin) Fly() string {

panic("I can't fly")

}

func (p *Penguin) Sing() string {

return "Penguin is singing."

}Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

This principle states that clients should not be forced to depend on interfaces they do not use.

If we violate this principle, we may have interfaces that are too large and contain methods that are not relevant to some clients, which can lead to code that is difficult to understand and maintain.

type Singer interface {

Sing() string

}

type Flyer interface {

Fly() string

}

type Pigeon struct{}

func (p *Pigeon) Fly() string {

return "Pigeon is flying."

}

func (p *Pigeon) Sing() string {

return "Pigeon is singing."

}

type Penguin struct{}

func (p *Penguin) Sing() string {

return "Penguin is screaming."

}Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

type Command interface {

Execute() ([]byte, error)

ValidateInput() bool

}Split your interfaces by behaviour or by clients, not by entities.

This principle encourages creating smaller, more focused interfaces rather than large, monolithic ones.

type Command interface {

Execute() ([]byte, error)

}

type CommandWithInput interface {

Command

ValidateInput() bool

}Don't

Do

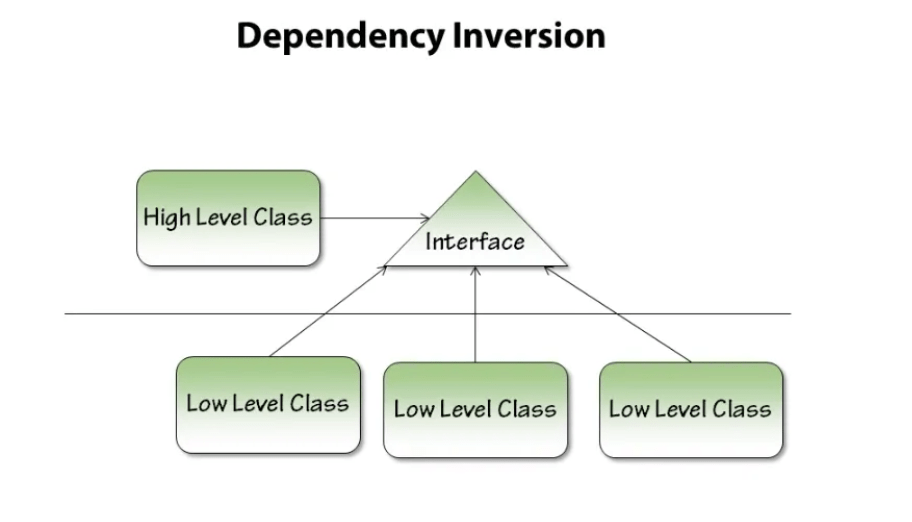

Dependency Inversion Principle (DIV)

type Mail struct {

from string

to []string

message string

}

func (m Mail) Send() error {

return smtp.SendMail("ssl0.ovh.net:587", "smtp-authentication", m.from, m.to, m.message)

}

type NotificationService struct {}

func (n NotificationService) Notify(m Mail) error {

// Do some stuff

return m.Send()

}Dependency Inversion Principle (DIV)

The Dependency Inversion Principle states that high-level modules should not depend on low-level modules, but both should depend on abstractions.

This principle promotes loose coupling between components, making the code more maintainable and testable.

Dependency Inversion Principle (DIV)

type Sender interface {

Send() error

}

type Mail struct {

from string

to []string

message string

}

func (m Mail) Send() error {

return smtp.SendMail("ssl0.ovh.net:587", "smtp-authentication", m.from, m.to, m.message)

}

type NotificationService struct {}

func (n NotificationService) Notify(s Sender) error {

// Do some stuff

return s.Send()

}Dependency Inversion Principle (DIV)

This principle is probably the most important of SOLID principles.

Strictly following this one will help you to keep a strong codebase, reactive to changes.

Interfaces

Interfaces will be a key feature to implement SOLID principles in our code.

It will help to loose coupling between components in a proper way.

Let's have an example!

A SOLID API

Let's understand how to properly use interfaces to separate different components of an application and loose coupling.

First of all, let's have a look on the existing codebase.

File to open:

craft/exercise1.mdadapters package

type UserSQL struct {

db *sql.DB

}

func NewUserSQL(db *sql.DB) user.Lister {

return &UserSQL{db: db}

}

func (u *UserSQL) List() ([]user.User, error) {

rows, err := u.db.Query(`SELECT firstname, lastname FROM users`)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

defer rows.Close()

users := make([]user.User, 0)

for rows.Next() {

var user user.User

if err := rows.Scan(&user.Firstname, &user.Lastname); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

users = append(users, user)

}

return users, nil

}user package

type Lister interface {

List() ([]User, error)

}type User struct {

Firstname string

Lastname string

}port.go

user.go

Fix the upper layer

Now that our user package is properly fixed, let's have a look on the http package.

File to open:

craft/exercise2.mdFix the upper layer

type Server struct {

listeningPort int

router *echo.Echo

user user.Lister

}

func NewServer(listeningPort int, user user.Lister) *Server {

router := echo.New()

server := &Server{

listeningPort: listeningPort,

router: router,

user: user,

}

router.GET("/user", server.GetUsers)

return server

}Fix the upper layer

func (s *Server) ListUsers(ctx echo.Context) error {

users, err := s.user.List()

if err != nil {

return ctx.JSON(http.StatusBadRequest, err.Error())

}

return ctx.JSON(http.StatusOK, users)

}Fixing the unit test?

Now we have to fix the unit test.

How to do it properly?

With a stub!

File to open:

craft/exercise3.mdFixing the unit test

type UserListerStub struct{}

func (u *UserGetterStub) List() ([]user.User, error) {

return []user.User{

{

Firstname: "SpongeBob",

Lastname: "SquarePants",

},

{

Firstname: "Patrick",

Lastname: "Star",

},

}, nil

}

var (

_ user.Lister = &UserListerStub{}

)Fixing the unit test

func TestListUsers(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

e := echo.New()

req := httptest.NewRequest(http.MethodGet, "/user", nil)

rec := httptest.NewRecorder()

c := e.NewContext(req, rec)

c.SetPath("/user")

server := &Server{user: &UserListerStub{}}

// Act

err := server.ListUsers(c)

// Assert

require.NoError(t, err)

require.Equal(t, http.StatusOK, rec.Code)

require.JSONEq(t,

`[{"Firstname": "SpongeBob", "Lastname": "SquarePants"}, {"Firstname": "Patrick", "Lastname": "Star"}]`,

rec.Body.String())

}Take a step back

With some simple usages of interfaces, we just removed a lot of coupling between our components.

Unit tests are often a really good indicator of the stickiness of your components together.

Even if it seems a bit overkill, this will help you to maintain a reliable codebase.

And (probably) without noticing, you just use a strong architecture pattern: the hexagonal architecture!

Hexagonal Architecture

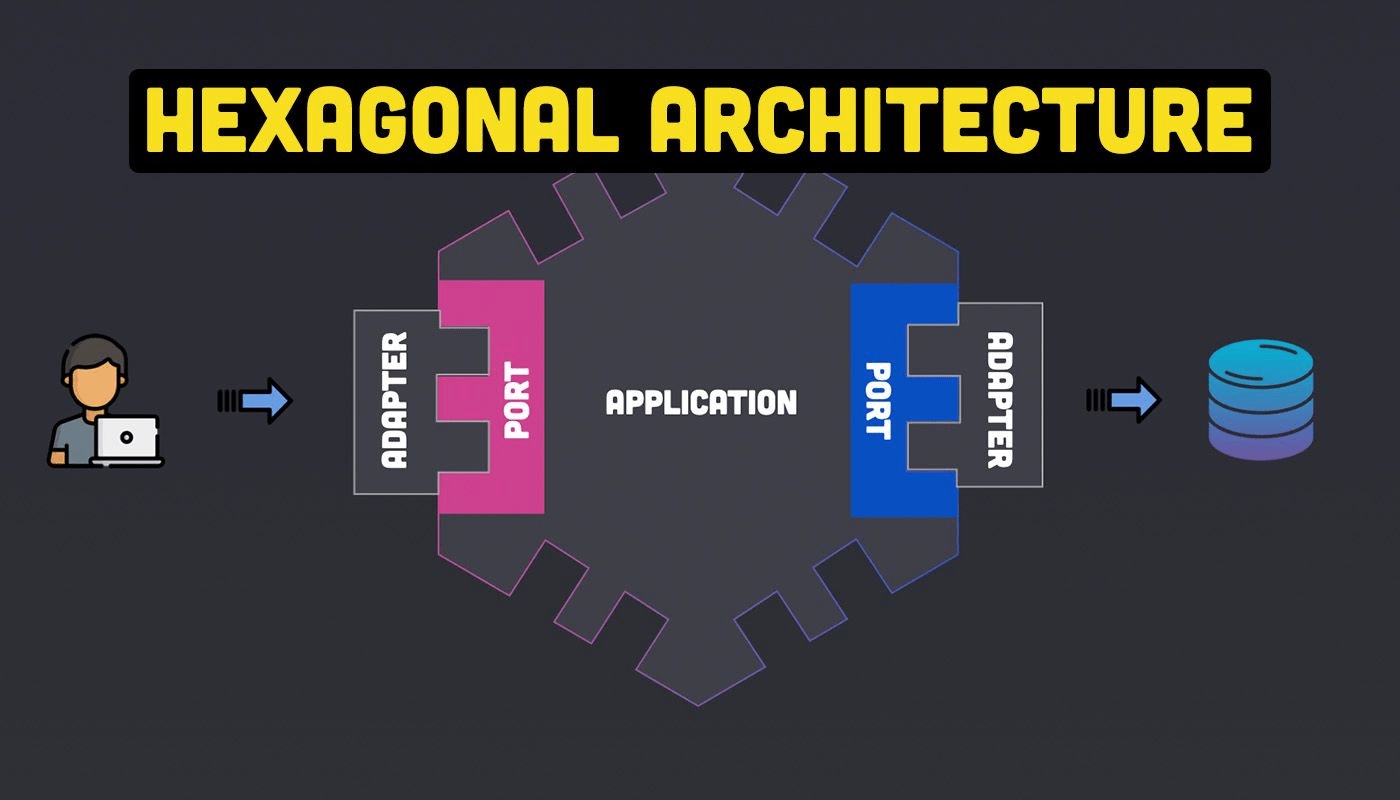

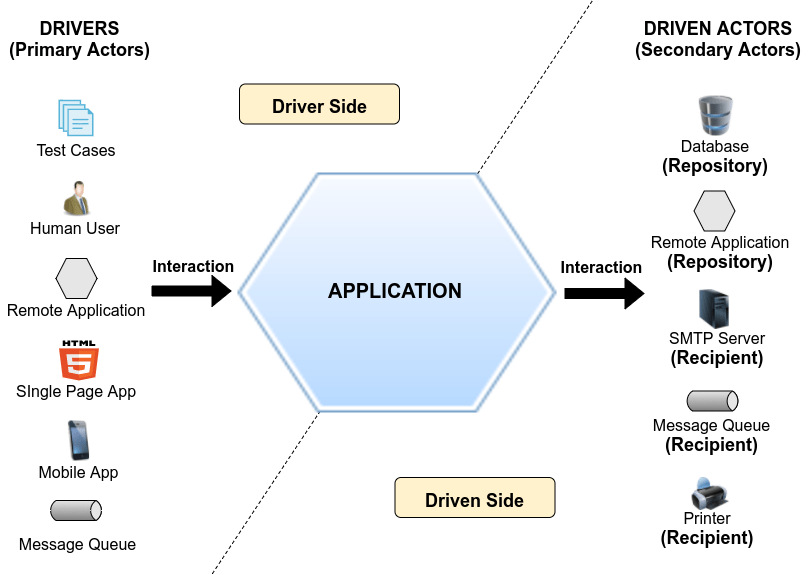

Hexagonal Architecture

Introduced by Alistair Cockburn (Agile Manifesto & Software Craft Manifesto) in 2005.

The Hexagonal Architecture aims at creating loosely coupled application components that can be easily connected to their software environment by means of ports and adapters. This makes components exchangeable at any level and facilitates test automation.

Hexagonal Architecture

Hexagonal Architecture

Goals

The application should be equally controllable by users, other applications, or automated tests.

For the business logic, it makes no difference whether it is invoked from a user interface, a REST API, or a test framework.

Goals

The business logic should be able to be developed and tested in isolation from the database, other infrastructure, and third-party systems.

From a business logic perspective, it makes no difference whether data is stored in a relational database, a NoSQL system, XML files, or proprietary binary format.

Goals

Infrastructure modernization (e.g., upgrading the database server, adapting to changed external interfaces, upgrading insecure libraries) should be possible without adjustments to the business logic.

Let's have a look on some code

Folder to open:

solution/hexagonal/Conclusion

Hexagonal Architecture is one of the many tools of the Software Craft perspective !

Using this port/adapter pattern can be a game changer for large codebase.

And Go is providing a proper way to do it thanks to interfaces!

Project organization

One layout to rule them all?

Go provides a small blog article to organize your code: https://go.dev/doc/modules/layout

There's also a non-official layout is proposed here: https://github.com/golang-standards/project-layout

This repository provides tips and usage on how properly create a new project in Go, based on what is recommended on the standard library, and what can be found in famous Go projects.

The internal directory

The internal directory is a feature introduced in Go 1.4, to limit the exposition of some functions to the outside.

It's a good way to define clear boundaries and avoid the usage of some pieces of code you want to keep internal to your package, without put those pieces as private.

The internal package

/api

/pkg

/account

/internal

/user

In this example, the user package:

- can be imported in pkg and account package

- cannot be imported in api package

This mechanism helps to manage the exposition of your code.

Concurrency

Concurrency

Concurrency in computing enables different parts of a program to execute independently, potentially improving performance and allowing better use of system resources.

Concurrency is the composition of independently executing tasks. It’s about dealing with a lot of things at once.

Concurrency is a way to structure a program by breaking it into pieces that can be executed independently.

Concurrency is not Parallelism

Parallelism is about doing a lot of things at once.

It’s a subset of concurrency, where the execution of tasks literally happens at the same time, like splitting the data processing task over multiple CPU cores.

In programming, concurrency is the composition of independently executing processes, while parallelism is the simultaneous execution of (possibly related) computations.

An example

Adding concurrency

Adding parallelism

goroutines

A Goroutine is a lightweight thread of execution.

The term comes from the phrase “Go subroutine”, reflecting the fact that Goroutines are functions or methods that run concurrently with others.

Starting a goroutine

package main

import "fmt"

func HelloWorld() {

fmt.Println("Hello world from my function!")

}

func main() {

go HelloWorld()

fmt.Println("Hello world from main!")

}The keyword go starts an execution in a goroutine.

What's the output of this program?

Waiting the end of a subroutine

By default, a goroutine starts a new concurrent process, leaving the main program to continue.

At the end of the main program, the program will stop, closing all goroutines even if their work is not finished.

Simple solution: let's add a time.Sleep!

Waiting the end of a subroutine

Not really elegant, isn't it?

Go provides other ways to do it:

- sync.WaitGroup

- channels

sync.WaitGroup

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

var waitgroup sync.WaitGroup

func HelloWorld() {

defer waitgroup.Done()

fmt.Println("Hello world from my function!")

}

func main() {

waitgroup.Add(1)

go HelloWorld()

fmt.Println("Hello world from main!")

waitgroup.Wait()

}Channels

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func HelloWorld(done chan bool) {

defer func() {

done <- true

}()

fmt.Println("Hello world from my function!")

}

func main() {

done := make(chan bool)

go HelloWorld(done)

fmt.Println("Hello world from main!")

<-done

}

Channels

Channels in Go are a conduit through which Goroutines communicate and synchronize execution.

They can transmit data of a specified type, allowing Goroutines to share information in a thread-safe manner.

Notably, they align with Go’s philosophy of “Do not communicate by sharing memory; instead, share memory by communicating.”

Channels

fmt.Println("receive from a channel")

boolFromChannel := <- channel

fmt.Println("received bool", boolFromChannel)Channels have two primary operations:

send and receive, denoted by the <- operator.

fmt.Println("send to a channel")

channel <- trueChannel operations are blocking

The send and receive operations are blocking by default.

When data is sent to a channel, the control is blocked in the send statement until some other Goroutine reads from that channel.

Similarly, if there is no data in the channel, a read from the channel will block the control until some Goroutine writes data to that channel.

Your first goroutines

Let's add some concurrency with a simple use case, using:

- WaitGroup

- Channel

File to open:

concurrency/exercise1.mdWaitGroup

func main() {

waitgroup := new(sync.WaitGroup)

for jobNumber := 0; jobNumber < 10; jobNumber++ {

waitgroup.Add(1)

go ConcurrentJob(jobNumber, waitgroup)

}

waitgroup.Wait()

}

func ConcurrentJob(jobNumber int, waitgroup *sync.WaitGroup) {

defer waitgroup.Done()

fmt.Printf("starting job %d\n", jobNumber)

time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(500)) * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Printf("ending job %d\n", jobNumber)

}Channels

func main() {

done := make(chan bool)

for jobNumber := 0; jobNumber < 10; jobNumber++ {

go ConcurrentJob(jobNumber, done)

}

for jobNumber := 0; jobNumber < 10; jobNumber++ {

<-done

}

}

func ConcurrentJob(jobNumber int, done chan bool) {

defer func() {

done <- true

}()

fmt.Printf("starting job %d\n", jobNumber)

time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(500)) * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Printf("ending job %d\n", jobNumber)

}Conclusion

As you might notice, concurrency can be easily done in Go.

But it requires a bit of practice to master it.

Working on concurrency often requires a bit of attention, and a lot of coffee!

What's next?

- Concurrency, going further: https://bwoff.medium.com/the-comprehensive-guide-to-concurrency-in-golang-aaa99f8bccf6

- Mastering Generics: https://medium.com/hprog99/mastering-generics-in-go-a-comprehensive-guide-4d05ec4b12b

- How to structure a Go application: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oL6JBUk6tj0

- Software Craft: https://www.dunod.com/sciences-techniques/software-craft-tdd-clean-code-et-autres-pratiques-essentielles

- Egoless Crafting: https://egolesscrafting.org/

- Hexagonal Architecture: https://blog.octo.com/architecture-hexagonale-trois-principes-et-un-exemple-dimplementation

Thanks! Questions?

Advanced features and Software Craft

By Nathan Castelein

Advanced features and Software Craft

- 211