Advanced Concurrency

SHODO

Hello! I'm Nathan.

- Co-founder of Shodo Lille

- Backend developer

- Pushing Go to production since 2014

- Worked 10 years at OVHcloud

- Inclusion & Diversity activist

- https://bento.me/nathan-castelein

What about you?

The next four hours

Schedule

Morning session

- 9h: Session start

- 10h: 5 minutes break

- 11h: 10 minutes break

- 12h: 5 minutes break

- 13h: Session ends

Afternoon session

- 14h: Session start

- 15h: 5 minutes break

- 16h: 10 minutes break

- 17h: 5 minutes break

- 18h: Session ends

What do you expect

from this training?

Content

- Introduction to concurrency

- Sync package

- Channels

- Concurrency patterns in Go

A four-hours training means ...

- A lot of resources will be provided to go further outside of the training session

- Some topics are excluded from this training session

- Sometimes, it's my point of view

- I'm available for any question following the session: nathan.castelein@shodo-lille.io

Prerequisites

- Go v1.21

- Git

Concurrency

What's concurrency programming?

Concurrency is about doing more than one thing at a time.

Concurrency is not (only) about parallelism. It's a bit more than that!

This is a property of a system. A concurrent system is one where a computation can advance without waiting for all other computations to complete.

Concurrency is everywhere: think about a simple web server !

Threads?

Concurrency is often discussed with threads and multithreading.

Are goroutines another name for threads? Not exactly.

Goroutines are part of the Go language since its first version. They're managed by the go runtime.

Goroutines vs. Threads

| Goroutines | Threads |

|---|---|

| Managed by go runtime | Managed by kernel |

| Not hardware dependent | Hardware dependent |

| Easy communication with channels | No easy communication medium |

| Fast communication | High-latency communication |

| Growable stack | No growable stack |

| Cheap | More expensive |

| Faster starter time | Slower starter time |

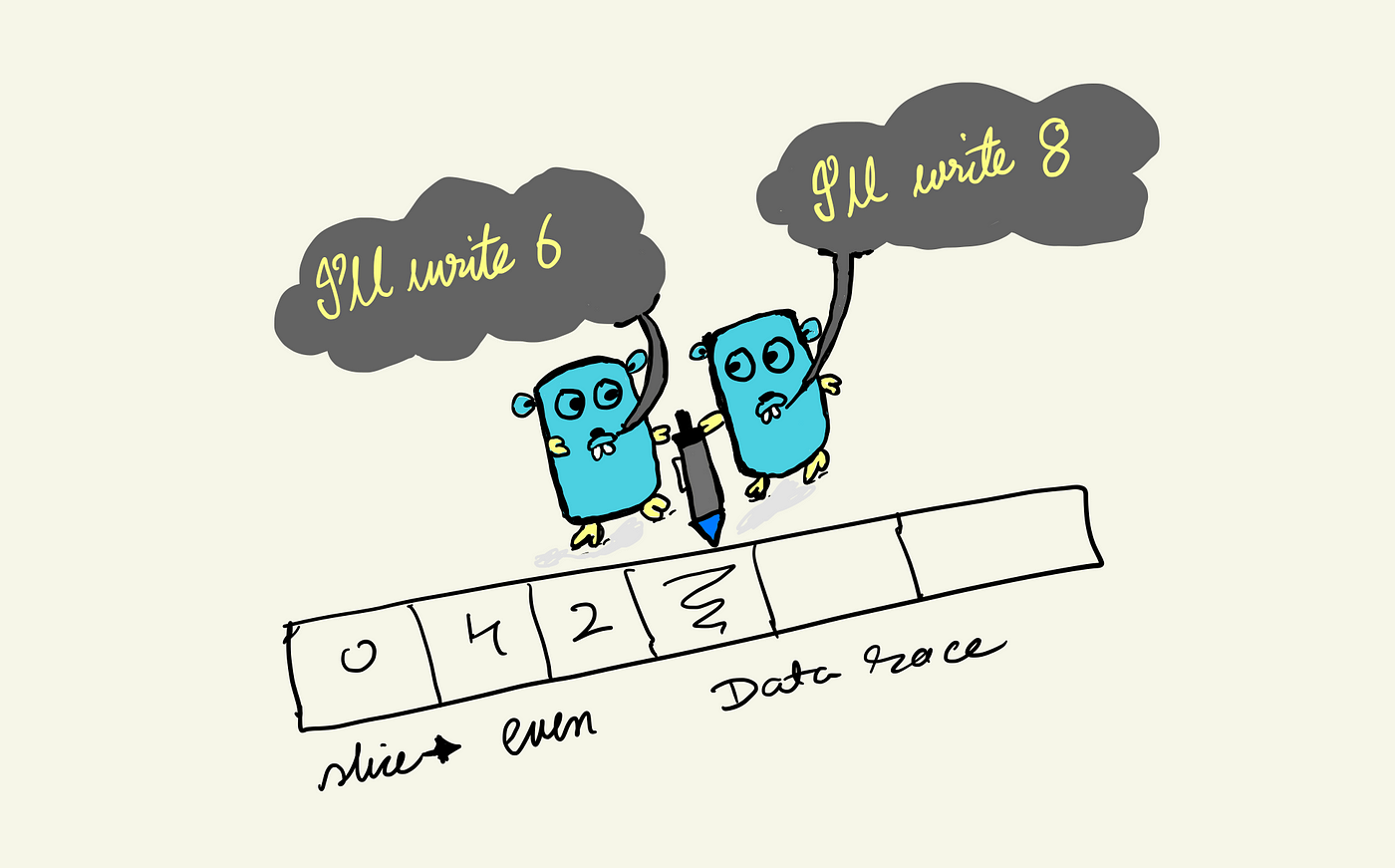

Concurrent programming: common issues

- Race conditions

- Deadlocks

- Resource starvation

Race conditions

Deadlocks

A deadlock is any situation in which no member of some group of entities can proceed because each waits for another member, including itself, to take action, such as sending a message or, more commonly, releasing a lock.

Edward G. Coffman described deadlocks in 1971!

Deadlocks

Following Coffmann's definition, a deadlock can occur only if the following conditions occur simultaneously:

- Mutual exclusion: At least one resource must be held in a non-shareable mode

- Hold and wait or resource holding: a process is currently holding at least one resource and requesting additional resources which are being held by other processes

- No preemption: a resource can be released only voluntarily by the process holding it

- Circular wait: each process must be waiting for a resource which is being held by another process, which in turn is waiting for the first process to release the resource

Resource starvation

Resource starvation is a problem encountered in concurrent computing where a process is perpetually denied necessary resources to process its work.

Avoiding those issues?

Go provides tools and patterns to avoid those issues.

We will take time to have a look on it during this workshop!

Concurrency patterns

Concurrency is a huge topic in computer science.

Many people worked on design patterns about concurrency:

- Worker pool

- Semaphore

- Pipeline

- Fan-in/Fan-out

- ...

We will explore some of them.

Sync package

Sync package

This package provides primitives to help while working with concurrency:

- WaitGroup

- Mutexes

- Once type

WaitGroup

Thanks to three methods, this type is a powerful tool to wait goroutines to end:

- Add: declare a new goroutine to wait for

- Done: a goroutine declares its end

- Wait: blocks and waits until all goroutines declared their end

WaitGroup

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

var urls = []string{

"http://www.golang.org/",

"http://www.google.com/",

"http://www.example.com/",

}

for _, url := range urls {

wg.Add(1)

go func(url string) {

defer wg.Done()

http.Get(url)

}(url)

}

wg.Wait()

}What do you think about this code?

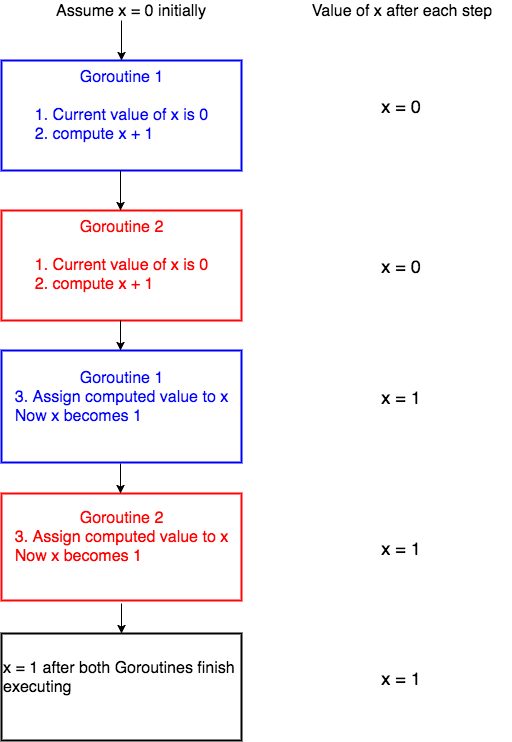

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

var x = 0

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for i := 0; i < 1000; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

x = x + 1

}()

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Printf("X = %d\n", x)

}

Mutexes

$ go run main.go

X = 951

$ go run main.go

X = 918

$ go run main.go

X = 966

$ go run main.go

X = 931

Go race detector

Go provides a tool to check for race conditions, with a -race flag available on build, test, run and install.

When the -race command-line flag is set, the compiler instruments all memory accesses with code that records when and how the memory was accessed.

Because of its design, the race detector can detect race conditions only when they are actually triggered by running code.

Go race detector

Race-enabled binaries can use ten times the CPU and memory. Thus it is not recommended to use it all the time. But it requires some workload to be efficient.

Use race-detector:

- During load tests or integration tests

- Deploy race flag one one of your pod in your production pool

Go race detector

$ go run -race main.go

==================

WARNING: DATA RACE

Read at 0x000104b51f00 by goroutine 16:

main.main.func1()

/Users/nathan/dev/training/go-course-concurrency/sync/mutex/example/main.go:19 +0x70

Previous write at 0x000104b51f00 by goroutine 10:

main.main.func1()

/Users/nathan/dev/training/go-course-concurrency/sync/mutex/example/main.go:19 +0x88

Goroutine 16 (running) created at:

main.main()

/Users/nathan/dev/training/go-course-concurrency/sync/mutex/example/main.go:15 +0x50

Goroutine 10 (finished) created at:

main.main()

/Users/nathan/dev/training/go-course-concurrency/sync/mutex/example/main.go:15 +0x50

==================Mutexes

var x = 0

var mu sync.Mutex

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for i := 0; i < 1000; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

mu.Lock()

defer mu.Unlock()

defer wg.Done()

x = x + 1

}()

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Printf("X = %d\n", x)

}Mutex

Let's add a mutex to prevent race condition.

File to open:

sync/mutex/exercise1.mdMutex

type Storage struct {

storage map[string]string

mu sync.Mutex

}

func (s *Storage) StoreIfNotExists(key, value string) {

s.mu.Lock()

defer s.mu.Unlock()

if _, exists := s.storage[key]; !exists {

slog.Info("store element")

s.storage[key] = value

} else {

slog.Info("element already exists")

}

}RWMutex

Sync package provides a RWMutex object with two sets of methods, one for the Read accesses, the other for the Write accesses:

- RLock() & RUnlock()

- WLock() & WUnlock()

It provides the opportunity to properly scope your locks.

Singleton pattern

In software engineering, the singleton pattern is a software design pattern that restricts the instantiation of a class to a singular instance.

We want to ensure a single instantiation!

Singleton pattern

type DB struct{ id string }

var (

databaseConnection *DB

)

func GetDB() *DB {

if databaseConnection == nil {

slog.Info("connecting to database")

databaseConnection = &DB{id: uuid.New().String()}

}

return databaseConnection

}func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

db := GetDB()

slog.Info("got database connection!", slog.Any("database", db))

}()

}

wg.Wait()

}Singleton pattern

$ go run *go

2024/06/30 15:10:06 INFO connecting to database

2024/06/30 15:10:06 INFO connecting to database

2024/06/30 15:10:06 INFO connecting to database

2024/06/30 15:10:06 INFO got database connection! database=&{id:fcb869f6-adda-4295-8c0c-9b113edcfc9b}

2024/06/30 15:10:06 INFO got database connection! database=&{id:15cfe965-1e21-4f84-ab48-97c5224bc87c}

2024/06/30 15:10:06 INFO got database connection! database=&{id:b62af6c7-73bc-4d12-9535-863ed6ad7883}Do we have only one instantiation?

Fix with a Mutex?

func GetDB() *DB {

mu.Lock()

defer mu.Unlock()

if databaseConnection == nil {

slog.Info("connecting to database")

databaseConnection = &DB{id: uuid.New().String()}

}

return databaseConnection

}func GetDB() *DB {

if databaseConnection == nil {

mu.Lock()

defer mu.Unlock()

slog.Info("connecting to database")

databaseConnection = &DB{id: uuid.New().String()}

}

return databaseConnection

}sync.Once

Go provides a tool for this issue: the sync.Once structure!

Once is an object that will perform exactly one action.

It provides only one method: Do(f func())

The f func() will be executed one time exactly for the same sync.Once variable.

sync.Once

Let's use sync.Once to fix the issue.

File to open:

sync/once/exercise1.mdsync.Once

type DB struct{ id string }

var (

databaseConnection *DB

once sync.Once

)

func GetDB() *DB {

once.Do(func() {

slog.Info("connecting to database")

databaseConnection = &DB{id: uuid.New().String()}

})

return databaseConnection

}sync.Once

type DB struct{ id string }

var (

databaseConnection *DB

once sync.Once

)

func GetDB() *DB {

if databaseConnection == nil {

once.Do(func() {

slog.Info("connecting to database")

databaseConnection = &DB{id: uuid.New().String()}

})

}

return databaseConnection

}Race detector is not happy with this!

sync/atomic

Last but not least, Go provides an atomic package to perform atomic actions on basic types in a concurrent environment.

We will not go deeper on this package, as it is recommended only on very low-level applications.

Channels

Channels

Channels are your best options to communicate between tasks.

Channels are simple but very strong when it comes to share data between multiple goroutines!

Channel features set

Channel provides a small features set:

- Create a channel (with a size)

- Read from a channel

- Send to a channel

- Close a channel

Create a channel

func main() {

var ch1 chan int

ch2 := make(chan int)

ch3 := make(chan int, 3)

}To properly create a channel, you must use the make instruction.

Channel is instanciated for a given type, that cannot be changed after.

Create a channel

The size of a channel is a very important notion, as it will change the behaviour of the channel.

A channel with a size greater than 0 is called buffered channel, or asynchronous channel.

A channel with a size of 0, or no size specified is called unbuffered channel, or synchronous channel.

Buffered channels

These channels possess a buffer size, which is beneficial when the sender needs to send data in bursts, while the receiver processes it at a different pace.

The buffer stores data temporarily, allowing the sender to continue sending without immediate blocking.

It’s crucial to select an appropriate buffer size.

If the buffer is full or if there is nothing to receive, a buffered channel will behave very much like an unbuffered channel.

Unbuffered channels

They ensure that data sent by the sender is immediately received by the receiver, leaving no room for delays.

It’s important to note that both sender and receiver must be ready before data can be sent or received.

Buffered or unbuffered?

Use unbuffered channels for synchronization: Unbuffered channels are useful for synchronizing the execution of two goroutines.

Use buffered channels for communication: Buffered channels can be used for asynchronous communication between goroutines.

One way channels

When using channels as function parameters, you can specify if a channel is meant to only send or receive values.

This specificity increases the type-safety of the program.

One way channels

func main() {

ch := make(chan string, 1)

sendOnlyFunc(ch)

receiveOnlyFunc(ch)

}

func receiveOnlyFunc(ch <-chan string) {

s := <-ch

fmt.Println(s)

}

func sendOnlyFunc(ch chan<- string) {

ch <- "hello"

}Read from a channel

myValue := <- myChannel

for myValue := range myChannel {

// process myValue

}The operator <- is used to read from a channel.

You can use the range statement to continually read values from a chan.

The range stops when channel is closed.

Closing a channel

Close channels when they are no longer needed.

Closing a channel indicates that no more data will be sent on that channel.

It is important to close channels when they are no longer needed to avoid blocking goroutines that are waiting to read from the channel.

Who close the channel?

If the channel is dedicated to a goroutine, it makes sense that the Sender is responsible for both sending data into the channel and closing it when no more data will be sent.

ch := make(chan int)

go func() {

for i:=0; i < 3; i++{

ch <- 1

}

close(ch)

}()Who close the channel?

var wg sync.WaitGroup

ch := make(chan int)

for i:= 0; i<3 ;i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func(i int){

defer wg.Done()

ch <- 1

}(i)

}

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(ch)

}()If the channel is shared between multiple goroutines which send data, then additional mechanisms like sync.WaitGroup may be needed to decide who gets to close the channel.

Operations on channels

| Operation | Nil chan | Closed chan | Not-nil not-closed chan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | panic | panic | succeed |

| Send value to | block for ever | panic | block or send |

| Receive value from | block for ever | never block | block or receive |

Signalling channels

func main() {

done := make(chan struct{})

go func() {

doLongRunningThing()

close(done)

}()

doOtherStuff()

<-done

}Signalling channels are a particular type of channels, where the data sent are not important and we just want to play with the block mechanism.

It is similar to a WaitGroup with a single element.

Select

Select

Before going further, let's introduce a new keyword in the language: select

Select statement is just like switch statement, but in the select statement, case statement refers to communication, i.e. sent or receive operation on the channel.

Select

func main() {

ch1 := make(chan string, 1)

defer close(ch1)

ch2 := make(chan string, 1)

defer close(ch2)

go func() {

time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(100)) * time.Millisecond)

ch1 <- "goroutine 1"

}()

go func() {

time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(100)) * time.Millisecond)

ch2 <- "goroutine 2"

}()

select {

case msg := <-ch1:

fmt.Printf("Hello from %s\n", msg)

case msg := <-ch2:

fmt.Printf("Hello from %s\n", msg)

}

}Select with timer and ticker

Let's use the select statement with a simple usecase.

file/to/open.go$ go test .File to open:

Test your code:

select/exercise1.mdSelect with timer and ticker

func TimerTicker(timerDuration time.Duration, tickerDuration time.Duration) {

timer := time.NewTimer(timerDuration)

ticker := time.NewTicker(tickerDuration)

for {

select {

case <-timer.C:

fmt.Println("Time to say goodbye")

ticker.Stop()

timer.Stop()

return

case <-ticker.C:

fmt.Println("Hello from ticker")

}

}

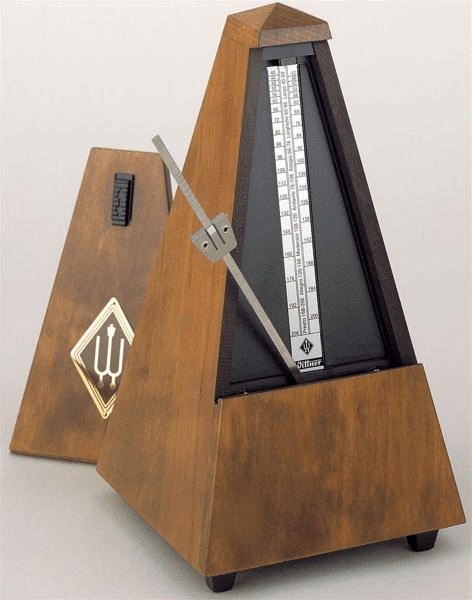

}Timer & Ticker

Timer & Ticker are two strong features of the time package.

Coupled with a select, it gives you a way to declare timeouts on some process!

time.After & time.Tick?

Time package provides two functions equivalent to time.Timer and time.Ticker:

- func After(d Duration) <-chan Time

- func Tick(d Duration) <-chan Time

But their usage is less recommended as it can leak some goroutines.

Concurrency patterns

Concurrency patterns

The history of software development with concurrency comes with a certain number of patterns.

Let's have a look on some of them that might be useful for your developments!

It's also a great way to understand the power and the easiness of concurrency in Go.

Our project

First of all, let's have a look on our project.

Adding some concurrency

Let's start simply by just adding some concurrency.

File to open:

datacenterfind/exercise1.mdAdding some concurrency

func WaitGroup(resourceName string, finders []Finder) {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for _, finder := range finders {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

slog.Info("starting find", slog.Any("datacenter", finder))

found := finder.Find(resourceName)

slog.Info("got result", slog.Any("datacenter", finder), slog.Bool("found", found))

}()

}

wg.Wait()

}The Scatter-Gather pattern

The Scatter-Gather pattern is a pattern where computation is first scattered, then all results are then gathered in a second step.

We want to separate the computation of the result and the handling of it.

The Scatter-Gather pattern

func WaitGroup(resourceName string, finders []Finder) {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for _, finder := range finders {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

slog.Info("starting find", slog.Any("datacenter", finder))

found := finder.Find(resourceName)

slog.Info("got result", slog.Any("datacenter", finder), slog.Bool("found", found))

}()

}

wg.Wait()

}Scatter-Gather pattern

Let's rewrite this function using channels!

File to open:

datacenterfind/exercise2.mdScatter-Gather pattern

func ScatterGather(resourceName string, finders []Finder) {

results := make(chan Result, len(finders))

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// Scatter

for _, finder := range finders {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

slog.Info("starting find", slog.Any("datacenter", finder))

results <- Result{

datacenter: finder,

found: finder.Find(resourceName),

}

}()

}

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(results)

}()

// Gather

for result := range results {

slog.Info("got result", slog.Any("datacenter", result.datacenter), slog.Bool("found", result.found))

}

}Redundant requests

This pattern provides a solution to a different issue: you want to spread one request per datacenter, but you are just interested into the first answer, not all the answers.

Once you have your first answer, then you can ignore (and cancel) the other calls.

Cancellation?

Go provides a way to cancel a goroutine using context.Context.

It requires a bit of work, as it requires your function to handle a context and its cancellation.

Cancellation

func (d *datacenter) FindWithContext(ctx context.Context, resourceName string) (bool, error) {

timer := time.NewTimer(d.responseDelay)

defer timer.Stop()

select {

case <-timer.C:

return true, nil

case <-ctx.Done():

slog.Info("deadline exceeded", slog.Any("finder", d))

return false, context.DeadlineExceeded

}

}To handle cancellation in your function, you need to accept a context.Context parameter, and handle when something is sent to ctx.Done().

Signature of this method: Done() <-chan struct{}

Cancellation

func main() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

doSomeStuff()

cancel()

}To obtain a cancellable context, you need to create it with the context.WithCancel function.

Redundant requests

Let's use cancellation contexts with redundant requests pattern.

File to open:

datacenterfind/exercise3.mdRedundant requests

func Redundant(resourceName string, finders []Finder) {

results := make(chan Result, len(finders))

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

for _, finder := range finders {

go func() {

slog.Info("launching find", slog.Any("datacenter", finder))

found, err := finder.FindWithContext(ctx, resourceName)

if err == nil {

results <- Result{

datacenter: finder,

found: found,

}

}

}()

}

result := <-results

cancel()

close(results)

slog.Info("got result", slog.Any("datacenter", result.datacenter), slog.Bool("found", result.found))

}With errors?

func (d *datacenter) FindWithError(ctx context.Context, resourceName string) (bool, error) {

// do some stuff

if err != nil {

return false, err

}

// do other stuff

}What if our function returns an error?

With errors?

func ErrGroup(resourceName string, finders []Finder) {

results := make(chan Result, len(finders))

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for _, finder := range finders {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

found, err := finder.FindWithError(context.TODO(), resourceName)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

results <- Result{

datacenter: finder,

found: found,

}

}()

}

wg.Wait()

close(results)

for result := range results {

slog.Info("got result", slog.Any("datacenter", result.datacenter), slog.Bool("found", result.found))

}

}Introducing ErrGroup

ErrGroup is a WaitGroup capable of handling errors.

Let's use it!

File to open:

datacenterfind/exercise4.mdIntroducing ErrGroup

func ErrGroup(resourceName string, finders []Finder) {

results := make(chan Result, len(finders))

errGroup, ctx := errgroup.WithContext(context.Background())

for _, finder := range finders {

errGroup.Go(func() error {

found, err := finder.FindWithError(ctx, resourceName)

if err != nil {

return err

}

results <- Result{

datacenter: finder,

found: found,

}

return nil

})

}

if err := errGroup.Wait(); err != nil {

slog.Error("an error occured", slog.String("error", err.Error()))

return

}

close(results)

for result := range results {

slog.Info("got result", slog.Any("datacenter", result.datacenter), slog.Bool("found", result.found))

}

}ErrGroup

ErrGroup handles the context cancellation as soon as one goroutine returns an error.

In our case, it can happen after some data have been sent to the channel.

It's up to you to decide to handle those data or to drop everything, regarding your needs.

Hedged requests in a nutshell:

- start one request

- if the request takes too much time, then start another one on a different backend

- repeat, until one of the requests provides an answer

This pattern avoids to send useless requests all over the world and overload your backends.

Hedged requests

func Hedged(resourceName string, finders []Finder) {

results := make(chan bool, len(finders))

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

for _, finder := range finders {

go func() {

slog.Info("launching find", slog.Any("datacenter", finder))

found, err := finder.FindWithContext(ctx, resourceName)

if err == nil {

results <- found

}

}()

}

found := <-results

cancel()

close(results)

slog.Info("got result", slog.Bool("found", found))

}Regarding everything you know about concurrency, how can we achieve this goal?

Hedged requests

Use a timer.Timer and a select statement to use the hedged requests pattern.

File to open:

datacenterfind/exercise5.mdHedged requests

func Hedged(resourceName string, finders []Finder) {

results := make(chan bool)

defer close(results)

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

defer cancel()

for _, finder := range finders {

timer := time.NewTimer(75 * time.Millisecond)

defer timer.Stop()

go func() {

slog.Info("launching find", slog.Any("datacenter", finder))

found, err := finder.FindWithContext(ctx, resourceName)

if err == nil {

results <- found

}

}()

select {

case result := <-results:

slog.Info("got result", slog.Bool("found", result))

return

case <-timer.C:

continue

}

}

}Semaphore pattern

Let's now get back to 2020. It's COVID time again. You're a baker.

Even if you have 200 chocolatines to sell for the day, it's 5 person maximum in your bakery.

So you need to limit the number of people in the same time in your bakery: welcome to the semaphore concurrency pattern!

Semaphore pattern

func Semaphore(resourceName string, finders []Finder) {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for _, finder := range finders {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

slog.Info("starting find", slog.Any("datacenter", finder))

found := finder.Find(resourceName)

slog.Info("got result", slog.Any("datacenter", finder), slog.Bool("found", found))

}()

}

wg.Wait()

}How can we achieve this?

Semaphore pattern

Let's implement the semaphore pattern!

File to open:

datacenterfind/exercise6.mdSemaphore pattern

func Semaphore(resourceName string, finders []Finder) {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

maxParallelAccesses := 2

semaphore := make(chan struct{}, maxParallelAccesses)

defer close(semaphore)

for _, finder := range finders {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

semaphore <- struct{}{}

defer func() { <-semaphore }()

slog.Info("starting find", slog.Any("datacenter", finder))

found := finder.Find(resourceName)

slog.Info("got result", slog.Any("datacenter", finder), slog.Bool("found", found))

}()

}

wg.Wait()

}Weighted semaphore

Let's go back to your bakery. The French President comes to buy some bread.

As it's the French President, he comes with 2 bodyguards. So even if it's only one customer, he took 3 spots in your bakery.

Weighted semaphore is a proper answer to this issue!

Some of your goroutines take more place (have a higher weight) than some other ones.

Weighted semaphore

Go provides an in-built library for weighted semaphore. Let's use it!

File to open:

datacenterfind/exercise7.mdWeighted semaphore

func WeightedSemaphore(resourceName string, finders []Finder) {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

sem := semaphore.NewWeighted(30)

ctx := context.Background()

for _, finder := range finders {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

if err := sem.Acquire(ctx, finder.Weight()); err != nil {

slog.Error("fail to acquire semaphore", slog.String("error", err.Error()))

return

}

defer sem.Release(finder.Weight())

slog.Info("starting find", slog.Any("datacenter", finder))

found := finder.Find(resourceName)

slog.Info("got result", slog.Any("datacenter", finder), slog.Bool("found", found))

}()

}

wg.Wait()

}Weighted semaphore

Be careful with weighted semaphore: if one of your weight is higher than the semaphore capacity, then your program will end in error because one of your goroutine will never be able to acquire the lock.

Can we rewrite our first semaphore with this standard library?

(Weighted) semaphore

func WeightedSemaphore(resourceName string, finders []Finder) {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

sem := semaphore.NewWeighted(2)

ctx := context.Background()

for _, finder := range finders {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

if err := sem.Acquire(ctx, 1); err != nil {

slog.Error("fail to acquire semaphore", slog.String("error", err.Error()))

return

}

defer sem.Release(1)

slog.Info("starting find", slog.Any("datacenter", finder))

found := finder.Find(resourceName)

slog.Info("got result", slog.Any("datacenter", finder), slog.Bool("found", found))

}()

}

wg.Wait()

}

What's next?

- Channels:

- Concurrency patterns:

Thanks! Questions?

Advanced Concurrency

By Nathan Castelein

Advanced Concurrency

- 111