Errors and logs

SHODO

Hello! I'm Nathan.

- Co-founder of Shodo Lille

- Backend developer

- Pushing Go to production since 2014

- Worked 10 years at OVHcloud

- Inclusion & Diversity activist

- https://bento.me/nathan-castelein

What about you?

The next four hours

Schedule

Morning session

- 9h: Session start

- 10h: 5 minutes break

- 11h: 10 minutes break

- 12h: 5 minutes break

- 13h: Session ends

Afternoon session

- 14h: Session start

- 15h: 5 minutes break

- 16h: 10 minutes break

- 17h: 5 minutes break

- 18h: Session ends

What do you expect

from this training?

Content

- Handling error properly

- Write efficient logs

- Check the performances of your code

- Security best practices

- A quick overview of diagnostics

- Tools to make build and release easier

A four-hours training means ...

- Something like 50% of theory, 50% of practice

- A lot of resources will be provided to go further outside of the training session

- Some topics are excluded from this training session

- Sometimes, it's my point of view

- I'm available for any question following the session: nathan.castelein@shodo-lille.io

Prerequisites

- Go v1.22

- Visual Studio Code

- Git

Error handling

The importance of error handling

https://golang.withcodeexample.com/blog/mastering-error-handling-logging-go-guide/

- User Experience: When errors occur, users expect clear and informative error messages. Handling errors gracefully enhances the user experience by providing understandable explanations and guidance on how to proceed.

- Stability: Unhandled errors can lead to program crashes or unexpected behavior, potentially compromising the stability of your application.

The importance of error handling

- Debugging: Properly handled errors provide developers with valuable insights into what went wrong. This information can be crucial for debugging and fixing issues.

- Maintainability: Code that handles errors effectively is easier to maintain and extend. It’s more resilient to changes and less prone to introducing new bugs.

If err != nil ...

There is a common pattern in Go to handle errors, sometimes described as a pain point of the language.

The pattern is ... to not handle it!

result, err := MyFunction()

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}Returning an error

When you get a non-nil error, you need to decide what to do with the error.

You have two choices:

- Stopping the error propagation. Do something with the error, like logging it or saving the error state in a database, then continue your process.

- Propagate the error, by returning it.

Depending of your current execution context, both approaches are fine.

Understanding the error type

Creating a new error

err := errors.New("something went wrong")

err := fmt.Errorf("invalid input: %s", input)Standard library provides ways to create a new error from a string, thanks to the errors package (https://pkg.go.dev/errors#New), or fmt package (https://pkg.go.dev/fmt#Errorf).

Fizzbuzz with error

Add error management on FizzbuzzWithError function.

Return an error if:

- Given number is 0

- Given number is negative

The error message must contain the invalid input.

file/to/open.go$ go test -run TestFizzBuzzWithErrorFile to open:

Test your code:

errorhandling/fizzbuzz.goFizzbuzz with error

func FizzbuzzWithError(input int) (string, error) {

if input == 0 {

return "", errors.New("input cannot be equal to 0")

}

if input < 0 {

return "", fmt.Errorf("input cannot be negative: %d", input)

}

return Fizzbuzz(input), nil

}Typed errors

For now, errors are just strings.

Let's now imagine we want to have different behaviours regarding the type of error. In our case with Fizzbuzz, imagine we have a process that calls Fizzbuzz:

- If input is equal to 0, then we just want to discard the error and continue the process

- If input is negative, then we want to stop the process

How can we properly handle this?

Sentinel errors

var ErrDivideByZero = errors.New("divide by zero")

func Divide(a, b int) (int, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0, ErrDivideByZero

}

return a / b, nil

}Your package can expose sentinel errors, ie. errors that can be checked for explicitely.

Checking a sentinel error

func main() {

result, err := Divide(30, 3)

if errors.Is(err, ErrDivideByZero) {

log.Fatal(err)

}

log.Infof("got result: %d", result)

}The errors package provides a function to check if an error is a sentinel error.

Before go 1.13

Before go 1.13, errors package didn't contained the errors.Is function.

Errors were checked with equality. This is not recommended anymore.

func main() {

result, err := Divide(30, 3)

if err == ErrDivideByZero {

log.Fatal(err)

}

log.Infof("got result: %d", result)

}Standard sentinel errors

Some examples of sentinel errors from standard packages:

- sql.ErrNoRows: https://pkg.go.dev/database/sql#pkg-variables

- io.EOF: https://pkg.go.dev/io#pkg-variables

func main() {

...

err := db.QueryRowContext(ctx, "SELECT username, created_at FROM users WHERE id=?", id).Scan(&username, &created)

if errors.Is(err, sql.ErrNoRows) {

...

}

}Fizzbuzz with sentinel error

Declare two new variables:

-

ErrZeroInput

-

ErrNegativeInput

Patch FizzbuzzWithSentinelError function to properly return your new errors.

Write MyFizzbuzzProcess function to fulfil the algorithm.

File to open:

errorhandling/fizzbuzz_sentinel.goFizzbuzz with sentinel error

var (

ErrZeroInput = errors.New("invalid input, can not be zero")

ErrNegativeInput = errors.New("invalid input, can not be negative")

)

func FizzbuzzWithSentinelError(input int) (string, error) {

if input == 0 {

return "", ErrZeroInput

}

if input < 0 {

return "", ErrNegativeInput

}

return Fizzbuzz(input), nil

}Fizzbuzz with sentinel error

func MyFizzbuzzProcess(input int) error {

result, err := FizzbuzzWithSentinelError(input)

if err != nil {

if errors.Is(err, ErrZeroInput) {

return nil

} else if errors.Is(err, ErrNegativeInput) {

return err

} else {

return err

}

}

fmt.Printf("Fizzbuzz of %d is %s\n", input, result)

return nil

}Conclusion

Sentinel error is a good way to go if you want to type an error.

But as errors are declared as variables, you can't add information inside an error.

What if we want to customise an error with some contextual data?

Introduce the error interface

type error interface {

Error() string

}The error type is actually...an interface!

Any type matching the interface can be used as an error.

Introduce the error interface

type DivideByZeroError struct {

value int

}

func (e DivideByZeroError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("cannot divide %d by zero", e.value)

}

func Divide(a, b int) (int, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0, DivideByZeroError{value: a}

}

return a / b, nil

}Matching a specific error

func main() {

result, err := Divide(10, 2)

if err != nil {

var divErr DivideByZeroError

if errors.As(err, &divErr) {

log.Fatalf("got a DivideByZeroError: %d", divErr.value)

} else {

log.Fatal("got an unexpected error")

}

}

fmt.Println(result)

}The errors package provides a function to cast an error to a specific type.

Create your own error

Create a new InvalidInput type, which stores the input, then implements the error interface and use the type in FizzbuzzWithCustomError.

Then use errors.As in MyFizzbuzzProcessWithCustomError.

file/to/open.go$ go test -run TestFizzBuzzWithCustomErrorFile to open:

Test your code:

errorhandling/fizzbuzz_custom_error.goCreate your own error

type InvalidInput struct {

input int

}

func (i InvalidInput) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("got invalid input %d", i.input)

}

func FizzbuzzWithCustomError(input int) (string, error) {

if input <= 0 {

return "", InvalidInput{input: input}

}

return errorhandling.Fizzbuzz(input), nil

}Create your own error

func MyFizzbuzzProcessWithCustomError(input int) error {

result, err := FizzbuzzWithCustomError(input)

if err != nil {

if errors.As(err, &InvalidInput{}) {

return nil

} else {

return err

}

}

fmt.Println(result)

return nil

}Error handling

Since the introduction of errors.As and errors.Is, using custom errors became simplier. Creating custom types is one of the good way to go.

No need to create a new error type for each error, do it when it is meaningful.

Wrapping errors

var ErrNotFound = errors.New("not found")

// FetchItem returns the named item.

//

// If no item with the name exists, FetchItem returns an error

// wrapping ErrNotFound.

func FetchItem(name string) (*Item, error) {

if itemNotFound(name) {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("%q: %w", name, ErrNotFound)

}

// ...

}Golang introduces a concept of wrapping errors. Using errors.Is and errors.As is preferred as it works with wrapping.

Wrapping errors

var ErrInvalidInput = errors.New("invalid input")

func FizzbuzzWithWrappingError(input int) (string, error) {

if input == 0 {

return "", fmt.Errorf("%w: input equals 0", ErrInvalidInput)

}

if input < 0 {

return "", fmt.Errorf("%w: input is negative: %d", ErrInvalidInput, input)

}

return errorhandling.Fizzbuzz(input), nil

}Wrapping errors

func TestFizzbuzzWithWrappingError(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

for _, input := range []int{0, -3} {

// Act

_, err := FizzbuzzWithWrappingError(input)

// Assert

if err == nil {

t.Fatal("test failed, expecting error but got nil")

}

if !errors.Is(err, ErrInvalidInput) {

t.Fatalf("test failed, expecting error type ErrInvalidInput")

}

}

}Some best practices

Define high level errors:

- ErrInvalidParameter

- ErrNotFound

- ErrInternal

- ...

Then wrap those errors into more defined errors. Depending of the context, the caller can check errors from a high level point of view, or a lower level one.

Panic

Something went wrong

Sometimes, your program can encounter some unexpected errors:

- Use of unitialized pointer

- Wrong slice iteration

- ...

Panic

panic: runtime error: index out of range [0] with length 0 [recovered]

panic: runtime error: index out of range [0] with length 0

goroutine 18 [running]:

testing.tRunner.func1.2({0x111c5e0, 0xc0000ae018})

/usr/local/go/src/testing/testing.go:1526 +0x24e

testing.tRunner.func1()

/usr/local/go/src/testing/testing.go:1529 +0x39f

panic({0x111c5e0, 0xc0000ae018})

/usr/local/go/src/runtime/panic.go:884 +0x213

github.com/nathancastelein/go-course-production/errorhandling.Panic()

/Users/nathan/dev/training/go-course-production/errorhandling/panic.go:8 +0x18

github.com/nathancastelein/go-course-production/errorhandling.TestPanic(0x0?)

/Users/nathan/dev/training/go-course-production/errorhandling/panic_test.go:6 +0x17

testing.tRunner(0xc000082b60, 0x1132e40)

/usr/local/go/src/testing/testing.go:1576 +0x10b

created by testing.(*T).Run

/usr/local/go/src/testing/testing.go:1629 +0x3ea

exit status 2A panic results in a crash of your program with a stacktrace

Panic

func ThisWillPanic() {

// Do something

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}A panic can also be raised manually. Not recommended, except when there's no other workaround.

Recovering from a panic: introduce the defer keyword

Before going further on panic recovery, meet the defer keyword!

A defer statement defers the execution of a function until the surrounding function returns.

The deferred call's arguments are evaluated immediately, but the function call is not executed until the surrounding function returns.

Defer

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

defer fmt.Println("world")

fmt.Println("hello")

}Defer

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

for i := 1; i <= 5; i++ {

defer fmt.Println(i)

}

}Defer can be used multiple times inside the same function. It "stacks" the functions to call at the end.

What is the output of this function?

Defer

Fix the WriteFile function to ensure file will always be closed.

File to open:

errorhandling/defer.goDefer

func WriteFile() error {

file, err := os.CreateTemp(os.TempDir(), "")

if err != nil {

return err

}

var closeError error

defer func() {

closeError = file.Close()

}()

for i := 0; i < 100; i++ {

res, err := FizzbuzzWithError(i)

if err != nil {

return err

}

file.WriteString(fmt.Sprintf("%d: %s", i, res))

}

return closeError

}Defer & Panic

func Panic() {

defer func() {

if r := recover(); r != nil {

fmt.Println("Recovered in f", r)

}

}()

fmt.Println([]int{}[0])

}Defer & Panic

Recovering from panic is often something to do on your main program.

It recovers from unexpected errors by avoiding your program to crash.

Web Frameworks provide middlewares to recover from panic (example: https://echo.labstack.com/docs/middleware/recover).

Conclusion

Error management in Go is unusual regarding other languages. This is why errors definition and management must be part of your development.

The toolkit provided by Go can help to define a good way of working with errors.

A part of handling errors is also to learn how to log it!

Log

Log

Standard package provides a simple logger: https://pkg.go.dev/log

Thanks to this package, you can create a logger, add prefix to each log (based on flags or custom).

It provides three helpers functions:

- Print: print the log

- Fatal: print and stop the program

- Panic: print and panic

Standard log package

The standard library provides a logging package, log, since Go’s initial release over a decade ago.

Over time, structured logging became important to Go programmers. Standard log package does not provide this feature.

A lot of different community packages were developed to fill this gap.

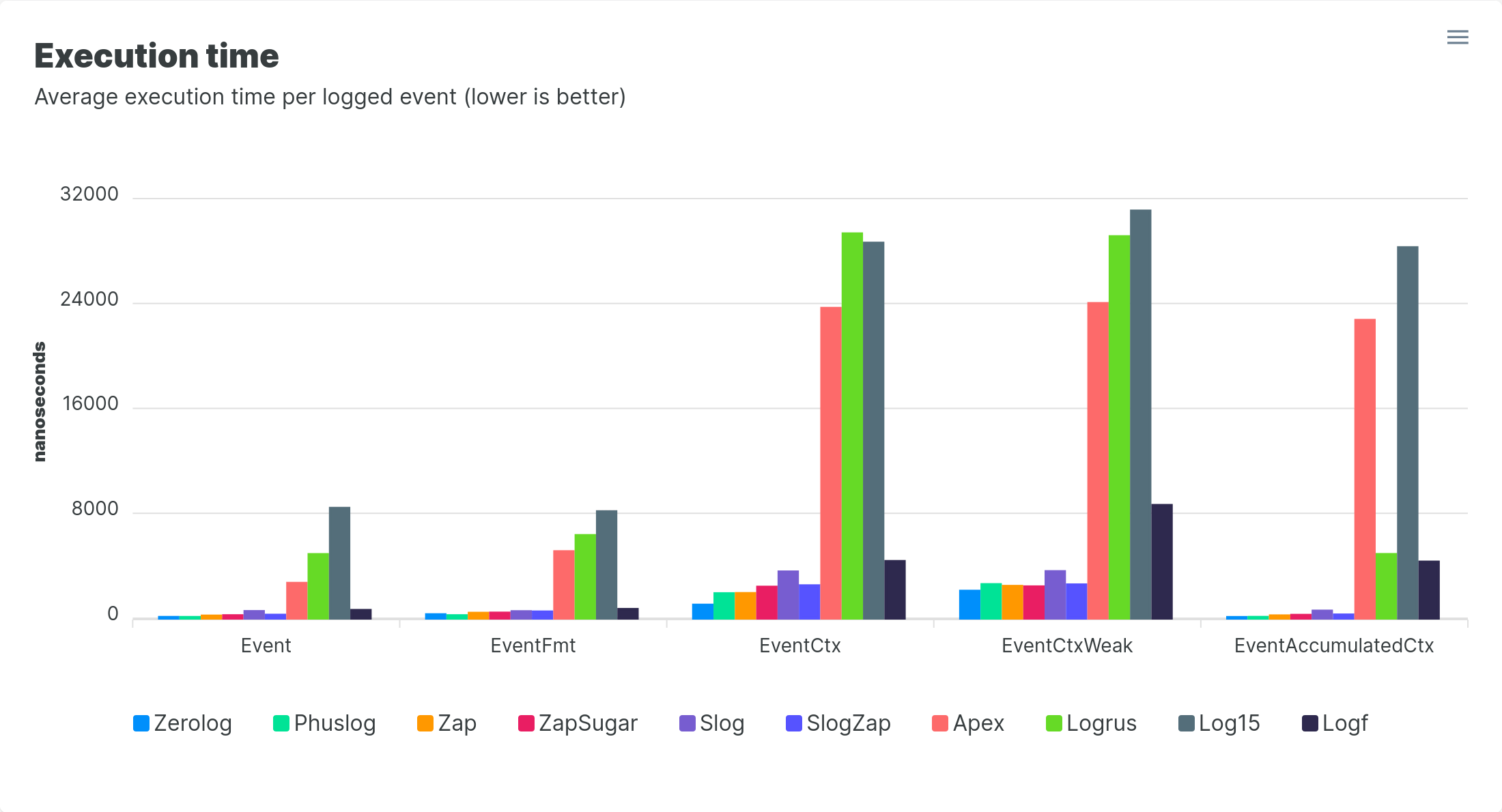

Famous log packages

| Name | Github | # of stars |

|---|---|---|

| Logrus | https://github.com/sirupsen/logrus | 24k |

| Zerolog | https://github.com/rs/zerolog | 10k |

| Zap | https://github.com/uber-go/zap | 21k |

| Log | https://github.com/apex/log | 1.5k |

| Glog | https://github.com/golang/glog | 3.5k |

Choosing the right log package

The logging library is something often hard to change when your project is in production.

How to choose the right log package?

By looking at the standard library since Go 1.21!

Introduce log/slog

slog, for structured logging

Structured logging is the practice of logging application and server errors or access events in a well-structured and consistent format that can be easily read, searched, and analyzed by any application or an interested individual.

Structured logging often implies:

- A datetime

- A message

- A severity (debug, info, warn, error)

- A context, expressed in key-value pairs

Structured logging

{

"time":"2023-02-24T11:52:49.554074496+01:00",

"level":"INFO",

"msg":"incoming request",

"method":"GET",

"time_taken_ms":158,

"path":"/hello/world?q=search",

"status":200,

"user_agent":"Googlebot/2.1 (+http://www.google.com/bot.html)"

}Initialise a new logger

logger := slog.New(slog.NewTextHandler(os.Stderr, nil))

logger.Info("bonjour", "user", "Nathan")

// Output: time=2022-11-08T15:28:26-05:00 level=INFO msg=bonjour user=Nathan

logger := slog.New(slog.NewJSONHandler(os.Stdout, nil))

logger.Info("bonjour", "user", "Nathan")

// Output: {"time":"2022-11-08T15:28:26-05:00","level":"INFO","msg":"bonjour","user":"Nathan"}slog provides way to create a new logger with different options

slog.Handler

To initialise a new logger, you need to provide a slog.Handler.

The handler defines how (and where) the log will be printed.

Handler is an interface that can implemented regarding your needs.

slog.Handler

Standard package provides two implementations:

- TextHandler: https://pkg.go.dev/log/slog@master#TextHandler

- JSONHandler: https://pkg.go.dev/log/slog@master#JSONHandler

You can also find Handler from the community!

Example with a GraylogHandler: https://github.com/samber/slog-graylog

Log level

const (

LevelDebug Level = -4

LevelInfo Level = 0

LevelWarn Level = 4

LevelError Level = 8

)Each log entry has a level, defining its severity. Level is defined by an integer. The higher the level, the more important or severe the event!

slog provides four levels by default, but there's room to add new ones.

Setting log level

logger := slog.New(slog.NewJSONHandler(os.Stdout, &slog.HandlerOptions{Level: slog.LevelInfo}))

logger := slog.New(slog.NewJSONHandler(os.Stdout, &slog.HandlerOptions{Level: slog.LevelDebug}))

logger := slog.New(slog.NewJSONHandler(os.Stdout, &slog.HandlerOptions{Level: slog.LevelWarn}))Defining the log level should be done according to the environment your code is running on. For example, debug are printed only on dev or staging environment, etc.

Log attributes

slog defines the concept of attributes (Attr). An attribute is a key-value pair that will give context to a log.

Attributes can be passed directly to a logger:

logger.Info("my log event", "user", "Nathan", "environment", "production")But it is safer and more efficient to use the Attr type to do so.

Attr

slog.Info("hello", slog.String("user", "Nathan"), slog.String("environment", "production"))

// Provided helpers:

slog.String("key", "value")

slog.Int("key", 42)

slog.Bool("key", true)

slog.Time("key", time.Now())

slog.Any("key", &User{Firstname: "Ada", Lastname: "Lovelace"})slog package provides helper to easily create Attr for common types.

The LogValuer interface

slog package gives you the possibility to define how a structure or a type will be displayed on the logs.

It gives you a way to protect some sensitive information to be printed on logs (password, token, etc.).

type LogValuer interface {

LogValue() Value

}LogValuer

type Email string

func (e Email) LogValue() slog.Value {

return slog.StringValue("*******@******.***")

}

type User struct {

Username string

Password string

}

func (u User) LogValue() slog.Value {

return slog.StringValue(u.Username)

}Default logger

func InitLogger() {

logger := slog.New(slog.NewJSONHandler(os.Stdout, nil)).

With(

slog.String("application", "api"),

)

slog.SetDefault(logger)

}In our main file, we defined a default logger for all our application.

Any code using slog.Info will use this logger.

Let's work with slog!

Use case: You're writing an API, and you want to add some logs on your API.

To do so, you create a new middleware to log each incoming request. Use slog.With to create a logger with new fields from the Default logger.

Open the first exercise. You can test your implementation with go test, or start the API using go run api/main.go!

File to open:

logging/exercise1.mdLogging middleware

func Logger() echo.MiddlewareFunc {

return func(next echo.HandlerFunc) echo.HandlerFunc {

return func(c echo.Context) error {

requestId := c.Request().Header.Get("X-Request-Id")

if requestId == "" {

requestId = uuid.New().String()

}

logger := slog.With(

slog.String("http_method", c.Request().Method),

slog.String("http_uri", c.Request().RequestURI),

slog.String("request_id", requestId),

)

logger.Info("handle request")

start := time.Now()

if err := next(c); err != nil {

return err

}

logger.Info("request handled", slog.Int64("elapsed_time", time.Since(start).Milliseconds()))

return nil

}

}

}Propagating the logger

To propagate the logger:

- Global variable

- Function parameter

- Field in struct

- Context

context.Context

The context.Context

Package context defines the Context type, which carries deadlines, cancellation signals, and other request-scoped values across API boundaries and between processes.

Do not store Contexts inside a struct type; instead, pass a Context explicitly to each function that needs it. The Context should be the first parameter, typically named ctx.

The context.Context

Incoming requests to a server should create a Context, and outgoing calls to servers should accept a Context.

The chain of function calls between them must propagate the Context, optionally replacing it with a derived Context.

At Google, we require that Go programmers pass a Context parameter as the first argument to every function on the call path between incoming and outgoing requests. This allows Go code developed by many different teams to interoperate well. It provides simple control over timeouts and cancellation and ensures that critical values like security credentials transit Go programs properly.

https://go.dev/blog/context

The context.Context

Contexts can be used for cancellation and propagation of the cancellation, especially when you work with goroutines.

It also provides an API to store key/values in a context.

Create a context

Two methods to create a new context:

- context.Background(): returns a non-nil, empty Context. It is typically used by the main function, initialization, and tests, and as the top-level Context for incoming requests.

- context.TODO(): returns a non-nil, empty Context. Use it when it's unclear which Context to use or it is not yet available.

context.WithValue

ctx := context.Background()

ctx = context.WithValue(ctx, "my-key", "my-value")Contexts are immutable objects, provided functions always create sub-context.

Retrieve a value

value := ctx.Value("my-key")

valueString, ok := value.(string)

if !ok {

... error

}Store and retrieve a value from context

Let's now provide two methods to manipulate the context:

- Store and retrieve the request id

- Store and retrieve the logger

File to open:

logging/exercise2.mdStore and retrieve a value from context

func NewContextWithRequestID(ctx context.Context, requestId string) context.Context {

return context.WithValue(ctx, "requestIdKey", requestId)

}

func GetRequestIDFromContext(ctx context.Context) (string, error) {

value := ctx.Value("requestIdKey")

if value == nil {

return "", ErrRequestIDNotFound

}

requestId, ok := value.(string)

if !ok {

return "", ErrRequestIDNotFound

}

return requestId, nil

}Store and retrieve a value from context

func NewContextWithLogger(ctx context.Context, logger *slog.Logger) context.Context {

return context.WithValue(ctx, "loggerKey", logger)

}

func GetLoggerFromContext(ctx context.Context) (*slog.Logger, error) {

value := ctx.Value("loggerKey")

if value == nil {

return nil, ErrLoggerNotFound

}

logger, ok := value.(*slog.Logger)

if !ok {

return nil, ErrLoggerNotFound

}

return logger, nil

}Using string for keys?

The linter is probably warning:

should not use built-in type string as key for value; define your own type to avoid collisions

It is not recommended to use string as key for value. It's better to define our own internal type!

Defining a type for keys

type key int

const (

requestIdKey key = 0

loggerKey key = 1

)

func NewContextWithRequestID(ctx context.Context, requestId string) context.Context {

return context.WithValue(ctx, requestIdKey, requestId)

}

...Get values from context

Usually, when providing functions to get a specific value from the context, you shouldn't return an error.

It's preferred to return a new instance of the requested object if not found.

func GetLoggerFromContext(ctx context.Context) *slog.Logger {

logger := ctx.Value(loggerKey).(*slog.Logger)

if logger == nil {

return slog.Default()

}

return logger

}Propagating the logger and request id with context

func Logger() echo.MiddlewareFunc {

return func(next echo.HandlerFunc) echo.HandlerFunc {

return func(c echo.Context) error {

...

ctx := c.Request().Context()

ctx = NewContextWithRequestID(ctx, requestId)

ctx = NewContextWithLogger(ctx, logger)

c.SetRequest(c.Request().WithContext(ctx))

...

}

}

}Let's now fix our middleware to store the logger in the context:

Add proper logs in handler

Now that everything is ready to propagate a contextualized logger, let's use it in our HTTP handler!

Remind that you can always start the API to see the result.

File to open:

logging/exercise3.mdAdd logs in handler

func Hello(c echo.Context) error {

user := c.QueryParam("user")

logger, err := GetLoggerFromContext(c.Request().Context())

if err != nil {

return err

}

logger.With(slog.String("user", user)).Info("saying hello")

if user == "" {

logger.Warn("empty user")

}

return c.String(http.StatusOK, fmt.Sprintf("Hello %s!", user))

}Performances

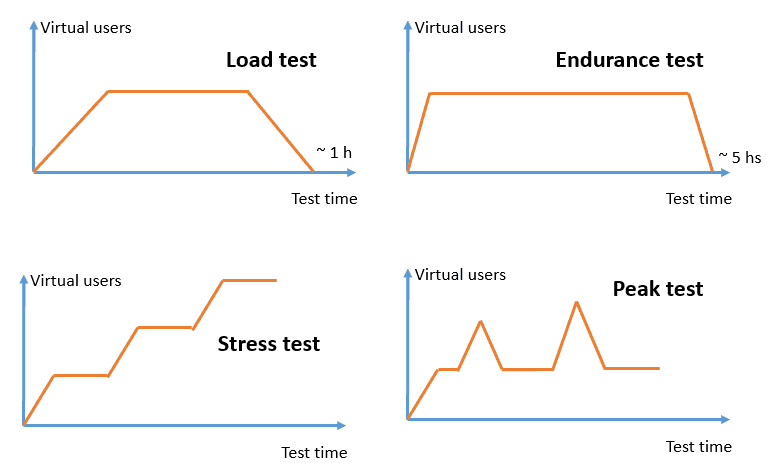

Performance testing

Performance testing assesses the speed, responsiveness, and stability of a software program, network, device, or web or mobile application under a specific workload.

There are multiple types of performance testing.

Performance testing

Benchmark testing

Benchmark testing

Benchmark testing is a subset of performance testing that refers to a set of metrics or a reference point against which you can quality check your software or applications.

The purpose of this testing is to compare the previous, present, and future updates of the application against a set reference.

Introduce testing.Benchmark

Go standard package provides tools to perform benchmarks easily.

Let's have a look on it!

We will see that writing benchmarks is quite easy. The most difficult part is to automate benchmarks comparisons through time.

Writing benchmarks

// fib.go

func Fib(n int) int {

if n < 2 {

return n

}

return Fib(n-1) + Fib(n-2)

}

// fib_test.go

func BenchmarkFib10(b *testing.B) {

// run the Fib function b.N times

for n := 0; n < b.N; n++ {

Fib(10)

}

}Benchmarks are written in *_test.go file. They follow a specific signature.

Let's operate a change and check benchmarks

Let's now add some benchmarks on our logging middleware.

Then we operate a change in the code, and we will check new performances.

File to open:

logging/exercise4.mdBenchstat

➜ logging git:(main) ✗ benchstat old.txt new.txt

goos: darwin

goarch: arm64

pkg: github.com/nathancastelein/go-course-production/solution/logging

│ old.txt │ new.txt │

│ sec/op │ sec/op vs base │

Logging-8 2.479µ ± 2% 2.727µ ± 2% +10.00% (p=0.000 n=10)

│ old.txt │ new.txt │

│ B/op │ B/op vs base │

Logging-8 1.328Ki ± 0% 1.445Ki ± 0% +8.82% (p=0.000 n=10)

│ old.txt │ new.txt │

│ allocs/op │ allocs/op vs base │

Logging-8 21.00 ± 0% 26.00 ± 0% +23.81% (p=0.000 n=10)The new implementation is less performant! Let's revert.

Automate benchmarks

To use the power of benchmarks, you need to compare your code before and after a change.

In a CI/CD point of view, it means running benchmarks on main, then on the branch ready to be merged, then compare the results.

Ideally, this should be run on the same machine.

benchstat and a bit of bash can help on this.

Security

Golang provides some best practices when writing Go code.

Let's have a look on it.

Check for vulnerabilities

➜ go-course-production git:(main) ✗ govulncheck ./...

Scanning your code and 168 packages across 14 dependent modules for known vulnerabilities...

No vulnerabilities found.Go provides a tool, named govulncheck, to check vulnerabilities. Use it in your CI/CD!

Code is checked for vulnerabilities known in a public database: https://vuln.go.dev/

If your code is using a vulnerable dependency, it will be raised by the tool.

Check for race conditions

Go has a built-in race detector. When you start to use concurrency in your program, checking for race conditions becomes a must have.

By using -race flag during go test, go build, go run, a warn will be printed on a race condition.

Look for hazardous code

Go vet is a tool to analyse code and check for strange patterns:

- Unreachable code

- Unused variables

- Useless assignments

- ...

➜ go-course-production git:(main) ✗ go vet ./...Vendor your imports

The go mod vendor command constructs a directory named vendor in the main module’s root directory containing copies of all packages needed to build and test packages in the main module.

go build and go test load packages from the vendor directory instead of accessing the network.

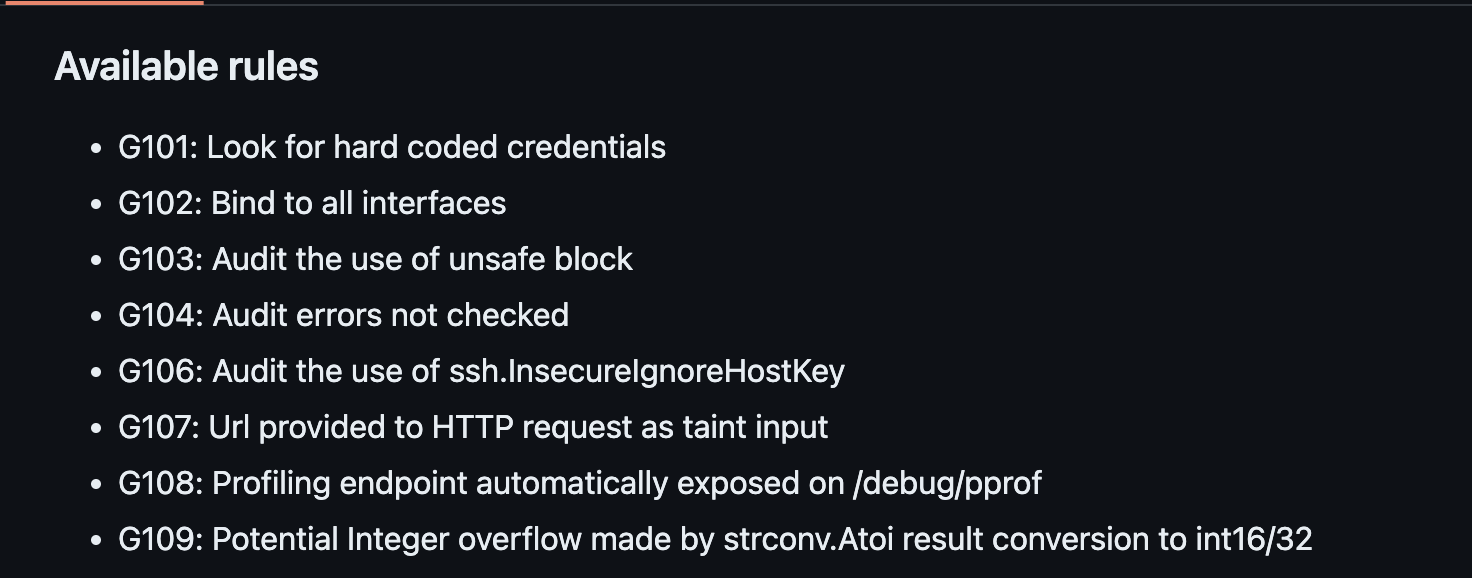

Use third-party tools

Gosec, for Go Security, Inspects source code for security problems.

It checks a list of known security issues:

Diagnostics

Diagnostics

https://go.dev/doc/diagnostics

When it comes to diagnose your code, you have multiple approaches:

- Profiling: Profiling tools analyze the complexity and costs of a Go program such as its memory usage and frequently called functions to identify the expensive sections of a Go program.

- Tracing: Tracing is a way to instrument code to analyze latency throughout the lifecycle of a call or user request. Traces provide an overview of how much latency each component contributes to the overall latency in a system. Traces can span multiple Go processes.

Diagnostics

https://go.dev/doc/diagnostics

- Debugging: Debugging allows us to pause a Go program and examine its execution. Program state and flow can be verified with debugging.

- Runtime statistics and events: Collection and analysis of runtime stats and events provides a high-level overview of the health of Go programs.

Go provides tools to help you on this. Those tools are complex and may require a specific module. We will not go deeper in this training session.

Profiling

The Go runtime provides profiling data in a pprof format. Data can then be visualized using dedicated tools.

Using predefined profiles can give you an overview of:

- CPU usage

- Heap and memory allocation

- Current goroutines

- Mutex and lock contention

- ...

Profiling

Data can be collected during go test, or can be exposed as an HTTP endpoint on your program.

// Adding HTTP routes

import _ "net/http/pprof"

// OR

import "github.com/labstack/echo-contrib/pprof"

router := echo.New()

pprof.Register(router)go tool pprof -http=localhost:8081 http://localhost:8080/debug/pprof/profile # 30-second CPU profile

go tool pprof -http=localhost:8081 http://localhost:8080/debug/pprof/heap # heap profile

go tool pprof -http=localhost:8081 http://localhost:8080/debug/pprof/block # goroutine blocking profileGoing further on profiling

Reading pprof documentation is a good start: https://github.com/google/pprof/blob/main/doc/README.md

There's also a blog post on go.dev: https://go.dev/blog/pprof

Quick introduction with working example: https://dev.to/agamm/how-to-profile-go-with-pprof-in-30-seconds-592a

Build to prod

GoReleaser

GoReleaser is designed to make the release of your code much more easier.

It helps you to cross-compile your code for different architectures, to release it on your release platform, to create Docker images with a signature, etc.

Buildpacks

Buildpacks, born in Heroku, is now a CNCF project aiming to make the building of container images much more easier and secure.

Instead of writing a Dockerfile, use Buildpacks to do it for you. It will be done according to compliance standards.

What's next?

- Write maintainable Go programs: https://dave.cheney.net/practical-go/presentations/qcon-china.html#_error_handling

- Write slog handlers: https://github.com/golang/example/blob/master/slog-handler-guide/README.md

- The ultimate guide to log with slog: https://betterstack.com/community/guides/logging/logging-in-go/

- Getting started with OpenTelemetry: https://opentelemetry.io/docs/languages/go/getting-started/

- Understanding context.Context: https://medium.com/@jamal.kaksouri/the-complete-guide-to-context-in-golang-efficient-concurrency-management-43d722f6eaea

- Profiling in Go: https://blog.stackademic.com/profiling-go-applications-in-the-right-way-with-examples-e784526e9481

Thanks! Questions?

Let's go to production

By Nathan Castelein

Let's go to production

- 221