Test your code

SHODO

Hello! I'm Nathan.

- Co-founder of Shodo Lille

- Backend developer

- Pushing Go to production since 2014

- Worked 10 years at OVHcloud

- Inclusion & Diversity activist

- https://bento.me/nathan-castelein

What about you?

The next four hours

Schedule

Morning session

- 9h: Session start

- 10h: 5 minutes break

- 11h: 10 minutes break

- 12h: 5 minutes break

- 13h: Session ends

Afternoon session

- 14h: Session start

- 15h: 5 minutes break

- 16h: 10 minutes break

- 17h: 5 minutes break

- 18h: Session ends

What do you expect

from this training?

Content

- Introduction to tests

- Unit testing in Go

- Mock

- Integration tests

A four-hours training means ...

- A lot of resources will be provided to go further outside of the training session

- Some topics are excluded from this training session

- Sometimes, it's my point of view

- I'm available for any question following the session: nathan.castelein@shodo-lille.io

Prerequisites

- Go v1.22

- Visual Studio Code

- Git

Introduction to tests

Why testing your code?

Software testing is a crucial activity in the software development life cycle that aims to evaluate and improve the quality of software products. Thorough testing is essential to ensure software systems function correctly, are secure, meet stakeholders’ needs, and ultimately provide value to end users.

https://www.computer.org/resources/importance-of-software-testing

Testing your code

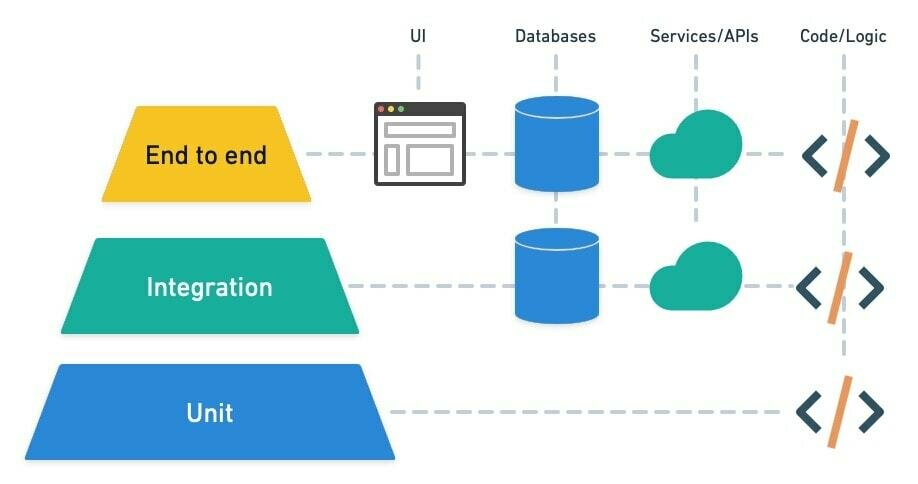

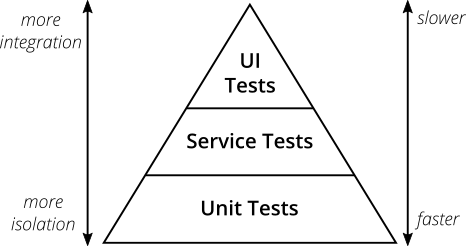

When it is time to test your code, you can have different approaches.

Martin Fowler provided a good overview of software testing thanks to a graphical approach: the Test Pyramid.

The Test Pyramid

The cost of Test Pyramid

Unit tests

Unit tests aim to validate the behaviour of a small piece of software, a "code unit". This "code unit" can be a method, a class, a function, ...

Integration tests

An integration test determines if some or all application components, after being unit tested, still operate properly while working together.

End to end tests

End to end tests check that all components, from the UI to the external dependencies (databases, external REST APIs, etc.) are working together.

Aiming for more quality

Automate your tests

Writing tests is a good start, but the good practice is to automate the run of your tests.

Unit tests should run automatically during your development process.

Integration and end to end tests should be launched through your continuous delivery.

Add performance and load tests

Ensure your application is working for a given numbers of users.

Define proper objectives, detect your SPOF, know the limits of your application.

Detect performances regressions between two versions of your application.

What about this training session?

In this training session, we will go through:

- Unit testing, a lot

- Some examples of integration testing

Unit testing

Unit testing: tests are F.I.R.S.T.

Unit tests should follow the F.I.R.S.T. approach:

- F: fast

- I: isolated, independent

- R: repeatable

- S: self-verifying

- T: timely, thorough

F, for fast

The feedback loop is a key point for good unit tests.

If launching unit tests is a pain point due to the execution time, then they will be skipped for productivity reasons.

Unit tests are not supposed to go over milliseconds, to ensure they are included during development and regularly launched.

I, for isolated, independent

A single test must be autonomous, and must not depend of other tests execution.

We should be able to run all tests in parallel, without any order of execution.

R, for repeatable

A unit test must be infinitely repeatable, on different environments.

The result must remain the same on a same codebase, whatever the environment.

If an application relies on the environment (like using time, etc.), we should substitute with a proper abstraction.

S, for self-verifying

The result of a test must be objectifiable. Either it's a positive result, either it's a failure.

In case of failure, the result must readable and understandable by itself.

Reading a failure must not require a deep human intervention.

T, for timely, thorough

Develop tests as opportunities: write use cases you think of, use bugs and issues to create new tests then fix your code. Waiting that your feature is written before thinking about tests makes your code harder to test.

One test should cover a maximum of one use case. Separate your use cases in multiple tests: nominal cases, borderline cases, error cases, etc.

Follow the F.I.R.S.T. approach

Following this approach will help you to write efficient tests. Ignoring it can result to write code hard to test or to maintain, or tests that are hard to launch on a regular basis.

More information: https://dzone.com/articles/first-principles-solid-rules-for-tests

Or chapter 8 of this (wonderful) book: https://www.dunod.com/sciences-techniques/software-craft-tdd-clean-code-et-autres-pratiques-essentielles

Unit testing in Go

Introduce the testing package!

Go provides a standard package for writing tests: https://pkg.go.dev/testing

This package is self-sufficient for quite all use cases. It's a simple package, but very powerful, combined with the go test command and its options.

Testing package in a nutshell

| Test | Write tests for your code (unit tests, integration tests) |

| Fuzzing | Write fuzzing tests for your code |

| Benchmark | Write benchmarks for your code |

Writing your first test

package math

import "testing"

func TestSum(t *testing.T) {

got := Sum(1, 2, 3)

if got != 6 {

t.Errorf("Sum(1, 2, 3) = %d; want 6", got)

}

}All tests must be written in a _test.go file.

package math

func Sum(numbers ...int) int {

sum := 0

for _, number := range numbers {

sum += number

}

return sum

}sum.go

sum_test.go

The *testing.T type

The testing.T type provides functions to:

- Log information during the test run

- Fail a test

- Skip a test

Logging and failing

Log

- t.Log("...") / t.Logf("..."): logs will be printed only if the test fails or with go test -v

Fail

- t.Fail(): marks the function as having failed but continues execution

- t.FailNow(): marks the function as having failed and stops its execution

Log & fail

- t.Error("...") / t.Errorf("..."): t.Log & t.Fail

- t.Fatal("...") / t.Fatalf("..."): t.Log & t.FailNow

Skipping

Skip

- t.SkipNow(): marks the test as having been skipped and stops its execution

- t.Skip("...") / t.Skipf("..."): t.Log & t.SkipNow

- testing.Short(): check if we are in a short mode

If a test fails and is then skipped, it's still considered as failed.

func TestAVeryLongTest(t *testing.T) {

if testing.Short() {

t.Skip("skipping test in short mode.")

}

...

}Run your tests

$ go test

$ go test -v

$ go test -run TestStuff

$ go test -skip TestStuff

$ go test -short

$ go test -timeout 1m

$ go test ./...Go test is your weapon to run your tests!

Run your tests: gotestsum

$ go install gotest.tools/gotestsum@latest

$ gotestsum --watch

Watching 3 directories. Use Ctrl-c to to stop a run or exit.Used to extend the go test output format. Run go test -json and change the output. Also provide a watcher!

Test FizzBuzz

Write 4 unit tests to test the behaviour of the FizzBuzz function:

- Return the same number when not multiple of 3 or 5

- Return Fizz when multiple of 3 but not 5

- Return Buzz when multiple of 5 but not 3

- Return FizzBuzz when multiple of 3 and 5

file/to/open.go$ go test .File to open:

Test your code:

unit/fizzbuzz/fizzbuzz_test.goTest FizzBuzz

func TestShouldReturnSameNumberWhenItIsNotMultipleOfThreeOrFive(t *testing.T) {

if result := Fizzbuzz(1); result != "1" {

t.Errorf("FizzBuzz(1) = %s; want 1", result)

}

}

func TestShouldReturnFizzWhenNumberIsMultipleOfThree(t *testing.T) {

if result := Fizzbuzz(3); result != "Fizz" {

t.Errorf("FizzBuzz(3) = %s; want Fizz", result)

}

}Testing: the AAA pattern

The AAA pattern

While writing tests, it becomes quite a standard to divide your test method into three sections:

- Arrange

- Act

- Assert

The AAA pattern

| Arrange | Set up the conditions for your test. This might involve creating objects, setting up variables or anything else that’s required for your test. |

| Act | This is where you actually execute the code that you are testing. |

| Assert | Verify that the code you’re testing behaves as expected. This might involve checking the value of a variable, or verifying that a certain method was called. |

Test FizzBuzz

func TestShouldReturnSameNumberWhenItIsNotMultipleOfThreeOrFive(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

number := 1

// Act

result := fizzbuzz.Fizzbuzz(number)

// Assert

if result != "1" {

t.Errorf("FizzBuzz(1) = %s; want 1", result)

}

}Back to FizzBuzz tests

You wrote four methods to unit test the different behaviours of the Fizzbuzz function.

A bit redundant, isn't it?

For this kind of situation, you can have a look on the table-driven tests pattern!

Table-Driven Tests

Table-driven tests

Table-driven is a test pattern to make tests easier to write when your tests differ in the Arrange part, but not in the Act and Assert part.

To do so, we will create a temporary structure to hold input values and expected values, then declare a slice to hold all use cases.

https://dave.cheney.net/2019/05/07/prefer-table-driven-tests

Table-driven tests

func TestSum(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

type test struct {

input []int

expected int

}

tests := []test{

{input: []int{1, 2, 3}, expected: 6},

{input: []int{0, 0, 1}, expected: 1},

{input: []int{5, 5}, expected: 10},

{input: []int{}, expected: 0},

}

for _, testcase := range tests {

// Act

got := Sum(testcase.input...)

// Assert

if got != testcase.expected {

t.Fatalf("expected: %v, got: %v", testcase.expected, got)

}

}

}Test FizzBuzz with TDT

Rewrite the 4 unit tests to a single test, using Table-Driven Tests pattern.

file/to/open.go$ go test -run TestFizzBuzzWithTableDrivenTestFile to open:

Test your code:

unit/fizzbuzz/fizzbuzz_tdt_test.goTest FizzBuzz with TDT

func TestFizzBuzzWithTableDrivenTest(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

type test struct {

input int

expected string

}

tests := map[string]test{

"should return same number when it is not multiple of three or five": {

input: 1,

expected: "1",

},

"should return Fizz when number is multiple of three": {

input: 3,

expected: "Fizz",

},

"should return Buzz when number is multiple of five": {

input: 5,

expected: "Buzz",

},

"should return FizzBuzz when number is multiple of three and five": {

input: 30,

expected: "FizzBuzz",

},

}

...Test FizzBuzz with TDT

func TestFizzBuzzWithTableDrivenTest(t *testing.T) {

...

// Act

for name, test := range tests {

result := Fizzbuzz(test.input)

// Assert

if result != test.expected {

t.Fatalf("%s failed, expected %s, got %s", name, test.expected, result)

}

}

}What if FizzBuzz is a long process?

Let's now imagine that FizzBuzz is a long process.

In your test, change the call to FizzBuzz to LongFizzBuzz then run go test!

func LongFizzbuzz(input int) string {

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond)

return Fizzbuzz(input)

}Two seconds later

By default, go test runs each test one by one, without parallelism.

But if you properly followed the F.I.R.S.T. approach, especially the Independent part, then your tests can be run in parallel!

The same issue comes with the table-driven tests, which are run sequentially.

The testing package provides a function to run tests in parallel.

Running tests in parallel

https://pkg.go.dev/testing#T.Parallel

Parallel signals that this test is to be run in parallel with (and only with) other parallel tests.

func TestShouldReturnSameNumberWhenItIsNotMultipleOfThreeOrFive(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

// Arrange

number := 1

// Act

result := fizzbuzz.Fizzbuzz(number)

// Assert

if result != "1" {

t.Errorf("FizzBuzz(1) = %s; want 1", result)

}

}Running table-driven tests in parallel?

The Parallel() function can be used inside a test to declare parallelism.

How to use parallelism with table-driven tests?

Run sub-tests

https://pkg.go.dev/testing#T.Run

Run runs a function as a subtest. It runs the function in a separate goroutine and blocks until the function returns or calls t.Parallel to become a parallel test.

func TestWithSubTests(t *testing.T) {

t.Run("first test", func(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

// do some stuff

})

t.Run("second test", func(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

// do some stuff

})

}Parallelism with go test

Once your code has been written to be executed in parallel, you can provide the -parallel n flag with the go test command.

This allows to manage parallel execution of tests written with t.Parallel().

By default, the flag value is set to the value of the GOMAXPROCS env variable. Providing a value higher than the max number of processors of your machine can result to CPU contention.

Adding sub-tests

Add sub-tests in the Table-Driven tests with t.Run and t.Parallel function.

file/to/open.go$ go test -run TestFizzBuzzWithTableDrivenTestAndParallelismFile to open:

Test your code:

unit/fizzbuzz/fizzbuzz_tdt_run_test.goAdding sub-tests

func TestFizzBuzzWithTableDrivenTestAndParallelism(t *testing.T) {

...

// Act

for name, test := range tests {

t.Run(name, func(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

result := LongFizzbuzz(test.input)

// Assert

if result != test.expected {

t.Fatalf("%s failed, expected %s, got %s", name, test.expected, result)

}

})

}

}Does it work properly?

Let's add some logs to check the behaviour.

Depending on your Go version, we will have some surprises...

func TestFizzBuzzWithTableDrivenTestAndParallelism(t *testing.T) {

...

t.Logf("executing test %s", name)

...

}Addind sub-tests

func TestFizzBuzzWithTableDrivenTestAndParallelism(t *testing.T) {

...

// Act

for name, test := range tests {

currentTest := test

currentName := name

t.Run(name, func(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

result := fizzbuzz.LongFizzbuzz(currentTest.input)

// Assert

if result != currentTest.expected {

t.Fatalf("%s failed, expected %s, got %s", currentName, currentTest.expected, result)

}

})

}

}An issue has been fixed in the latest version of Go, the Go 1.22.

You can check all information here: https://go.dev/wiki/LoopvarExperiment

Clojures and goroutines

Coverage

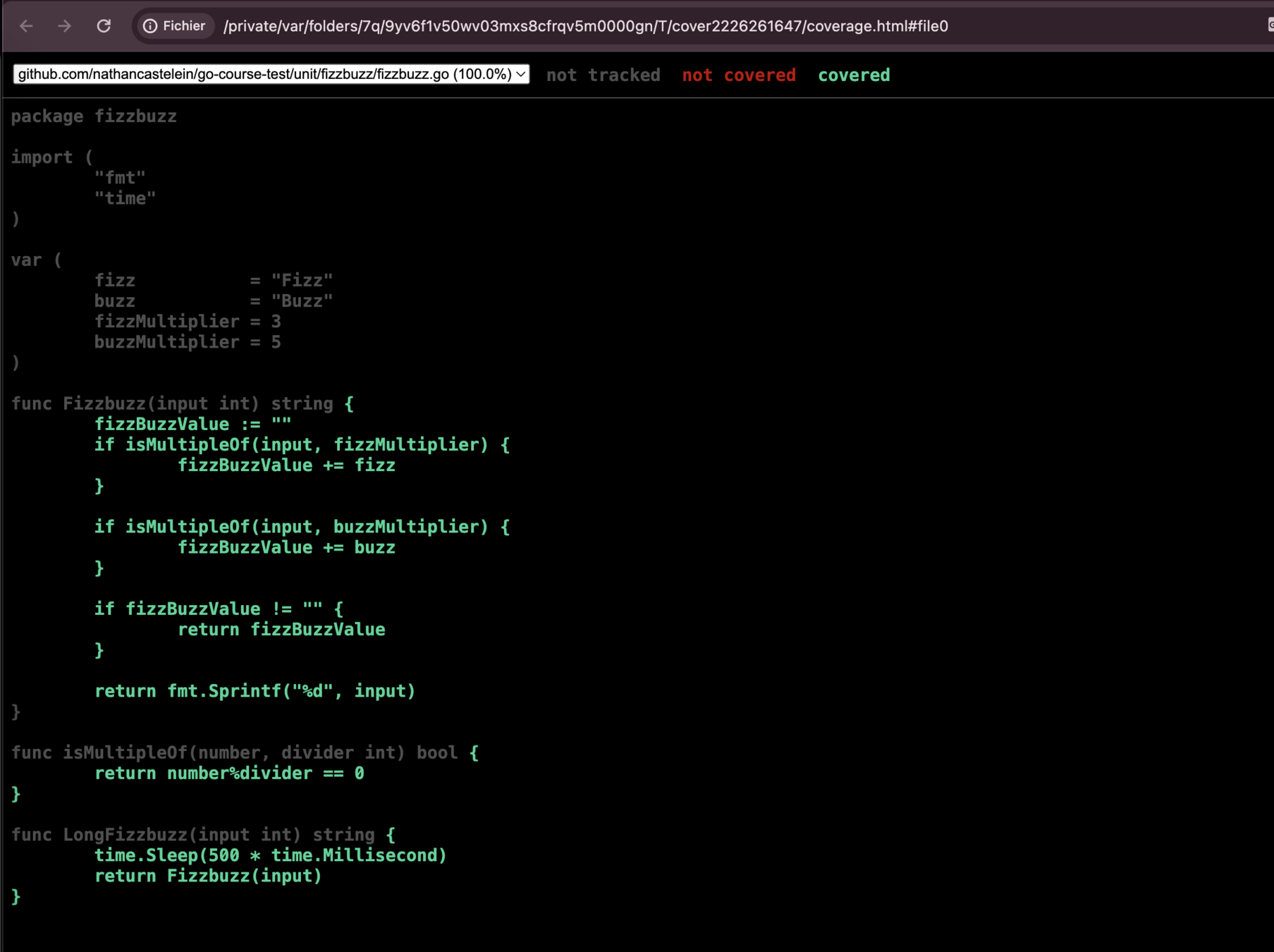

Test coverage

In software engineering, code coverage is a percentage measure of the degree to which the source code of a program is executed when a particular test suite is run. A program with high test coverage has more of its source code executed during testing, which suggests it has a lower chance of containing undetected software bugs compared to a program with low test coverage.

Test coverage

$ go test -cover

ok github.com/nathancastelein/go-course-test/unit/fizzbuzz 2.385s coverage: 100.0% of statements

$ go test -coverprofile=cover.out

$ go tool cover -html="cover.out"Go test provides an easy way to generate coverage.

cover.html

Visual Studio Code can be configured to show coverage in the IDE.

Coverage

The coverage is an indicator of the part of the code which is unit tested.

Aiming for a good coverage percentage can be a good quality measurement, but aiming for 100% is a non-sense.

Write tests because you need them, not to only increase the coverage.

Fuzz testing

Fuzz testing

Fuzz testing or fuzzing is an automated software testing method that injects invalid, malformed, or unexpected inputs into a system to reveal software defects and vulnerabilities. A fuzzing tool injects these inputs into the system and then monitors for exceptions such as crashes or information leakage.

Fuzz testing has been introduced in Go 1.18: https://go.dev/doc/security/fuzz/

Tutorial: https://go.dev/doc/tutorial/fuzz

Fuzz testing

There are two modes of running fuzz tests: as a unit test (with go test) or with fuzzing (go test -fuzz=FuzzXXX).

Running with fuzzing will generate many different inputs to inject in your function, to test strange behaviours.

Fuzz testing

func FuzzReverse(f *testing.F) {

f.Add("Hello world")

f.Add("This is a corpus")

f.Fuzz(func(t *testing.T, orig string) {

rev := Reverse(orig)

doubleRev := Reverse(rev)

if orig != doubleRev {

t.Errorf("Before: %q, after: %q", orig, doubleRev)

}

if utf8.ValidString(orig) && !utf8.ValidString(rev) {

t.Errorf("Reverse produced invalid UTF-8 string %q", rev)

}

})

}Fuzz testing

go test

Run fuzzing only with the corpus.

go test -fuzz=Fuzz

Run fuzzing with the corpus and with generated inputs.

Stops on an error.

Add -fuzztime=5s to stop after a given time.

Fuzzing in FizzBuzz?

How can we use fuzzing to detect issues on FizzBuzz?

Fuzzing in FizzBuzz

Write the FuzzFizzbuzz unit test with fuzzing to check that:

- Either output is one of Fizz, Buzz or FizzBuzz

- Either output can be converted to a number and is the input number

file/to/open.go$ go test -run=Fuzz -fuzz=Fuzz -fuzztime=5sFile to open:

Test your code:

unit/fizzbuzz/fizzbuzz_fuzzing_test.goFuzz testing FizzBuzz

func FuzzFizzbuzz(f *testing.F) {

f.Add(1) // Use f.Add to provide a seed corpus

f.Add(3)

f.Add(5)

f.Add(30)

f.Fuzz(func(t *testing.T, number int) {

result := Fizzbuzz(number)

switch result {

case "Fizz", "Buzz", "FizzBuzz":

return

default:

numberFromString, err := strconv.Atoi(result)

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("got invalid result for input %d: %s (error %s)", number, result, err)

}

if numberFromString != number {

t.Fatalf("number should not be different: expected %d got %d", number, numberFromString)

}

}

})

}Fuzz testing FizzBuzz

$ go test -fuzz=Fuzz -fuzztime=5s

fuzz: elapsed: 0s, gathering baseline coverage: 0/4 completed

fuzz: elapsed: 0s, gathering baseline coverage: 4/4 completed, now fuzzing with 8 workers

fuzz: elapsed: 3s, execs: 776964 (258970/sec), new interesting: 4 (total: 8)

fuzz: elapsed: 5s, execs: 1289080 (248523/sec), new interesting: 4 (total: 8)

PASS

ok github.com/nathancastelein/go-course-test/solution/unit/fizzbuzz 6.048sMock

Mocks, or tests double?

In 2006, Martin Fowler wrote about "Test Double". Test Double is a generic term for any case where you replace a production object for testing purposes.

There are various kinds of double:

- Dummy objects are passed around but never actually used. Usually they are just used to fill parameter lists.

- Fake objects actually have working implementations, but usually take some shortcut which makes them not suitable for production (an InMemoryTestDatabase is a good example).

Mocks, or Test Double?

- Stubs provide canned answers to calls made during the test, usually not responding at all to anything outside what's programmed in for the test.

- Spies are stubs that also record some information based on how they were called. One form of this might be an email service that records how many messages it was sent.

- Mocks are pre-programmed with expectations which form a specification of the calls they are expected to receive. They can throw an exception if they receive a call they don't expect and are checked during verification to ensure they got all the calls they were expecting.

Mocks, or Test Double?

You probably never heard about Test Double, but more often about mocks, or mocking. Mocks are a part of Test Double, but is more and more used to replace the term "Test Double".

Mocks and Go

Let's now have a look on how to use mocks to test code with dependancies to:

- HTTP API

- SQL

Mock HTTP

httptest

By the standard: httptest

Go provides a standard package for http unit tests: httptest

This library provides tools to:

- Test http handlers: create http.Request and http.ResponseWriter recorder to test a handler

- Test requests to an external server: create http.Server as an endpoint for your calls

Test http handlers

func HelloWorldHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintln(w, "Hello world!")

}We want to test this handler:

Test http handlers

func TestHelloWorldHandler(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

request := httptest.NewRequest(http.MethodGet, "/", nil)

responseRecorder := httptest.NewRecorder()

// Act

HelloWorldHandler(responseRecorder, request)

// Assert

if responseRecorder.Code != http.StatusOK {

t.Fatalf("expected status code %d, got %d", http.StatusOK, responseRecorder.Code)

}

body, err := io.ReadAll(responseRecorder.Body)

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("got an error while reading body: %s", err)

}

if string(body) != "Hello world!\n" {

t.Fatalf("expected body Hello world!, got %s", string(body))

}

}Test http requests

func HelloHTTPCall(url string) (string, error) {

res, err := http.Get(url + "/hello")

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

body, err := io.ReadAll(res.Body)

defer res.Body.Close()

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

return string(body), nil

}We want to test this function:

Test http requests

func TestHelloHTTPCall(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

testServer := httptest.NewServer(http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if r.Method != http.MethodGet {

t.Fatalf("expected method GET, got %s", r.Method)

}

if r.URL.Path != "/hello" {

t.Fatalf("expected path /hello, go %s", r.URL.Path)

}

fmt.Fprintln(w, "Hello world!")

}))

defer testServer.Close()

// Act

result, err := HelloHTTPCall(testServer.URL)

// Assert

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("got an error while making call: %s", err)

}

if result != "Hello world!\n" {

t.Fatalf("expected body Hello world!, got %s", result)

}

}gock

Using gock

- Intercepts any HTTP outgoing request via http.DefaultTransport or custom http.Transport used by any http.Client.

- Matches outgoing HTTP requests against a pool of defined HTTP mock expectations in FIFO declaration order.

- If at least one mock matches, it will be used in order to compose the mock HTTP response.

- If no mock can be matched, it will resolve the request with an error, unless real networking mode is enable, in which case a real HTTP request will be performed.

A piece of code to test

func PerformRequest() (*http.Response, error) {

response, err := http.Get("http://myapi.com")

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return response, nil

}Using Gock

func TestPerformRequest(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

defer gock.Off()

gock.New("http://myapi.com").

Get("/").

Reply(http.StatusOk)

// Act

response, err := PerformRequest()

// Assert

...

}Using Gock

gock.New("http://foo.com").

MatchHeader("Authorization", "^foo bar$").

HeaderPresent("Accept").

MatchParam("page", "1").

PathParam("user", "123").

MatchType("json").

JSON(map[string]string{"foo": "bar"}).

Reply(http.StatusOK).

SetHeader("Server", "gock").

BodyString("foo foo").

JSON(map[string]string{"foo": "bar"})Code to test

type Information struct {

FirstName string `json:"first_name"`

LastName string `json:"last_name"`

}

func GetInfos(userId int) (*Information, error) {

response, err := http.Get(fmt.Sprintf("https://yourapitomock.io?user=%d", userId))

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

if response.StatusCode != http.StatusOK {

return nil, errors.New("invalid status code received")

}

defer response.Body.Close()

body, err := io.ReadAll(response.Body)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

info := &Information{}

err = json.Unmarshal(body, info)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return info, nil

}Testing GetInfo

Using Gock, add unit test for GetInfo.

file/to/open.go$ go test -run TestGetInfoFile to open:

Test your code:

unit/mocking/http_test.goTesting GetInfo

func TestGetInfo(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

defer gock.Off() // Flush pending mocks after test execution

gock.New("https://yourapitomock.io").

Get("/").

MatchParam("user", "1").

Reply(http.StatusOK).

JSON(map[string]string{

"first_name": "Parisa",

"last_name": "Tabriz",

})

// Act

info, err := mocking.GetInfo(1)

// Assert

...

}Testing AddUser

Using Gock, add unit test for AddUser.

file/to/open.go$ go test -run TestAddUserFile to open:

Test your code:

unit/mocking/http_test.goTesting AddUser

func TestAddUser(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

defer gock.Off() // Flush pending mocks after test execution

gock.New("https://yourapitomock.io").

Post("/user").

MatchType("application/json").

JSON(&mocking.Information{FirstName: "Grace", LastName: "Hopper"}).

Reply(http.StatusOK).

JSON(map[string]int{"id": 42})

// Act

id, err := mocking.AddUser(&mocking.Information{FirstName: "Grace", LastName: "Hopper"})

// Assert

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("unexpected error: %s", err)

}

if id != 42 {

t.Fatal("id is expected to be 42")

}

}Testing UpdateUser

Using Gock, add unit test for UpdateUser.

file/to/open.go$ go test -run TestUpdateUserFile to open:

Test your code:

unit/mocking/http_test.goTesting UpdateUser

func TestUpdateUser(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

defer gock.Off() // Flush pending mocks after test execution

gock.New("https://yourapitomock.io").

Put("/user/1").

MatchType("application/json").

JSON(&mocking.Information{FirstName: "Grace", LastName: "Hopper"}).

Reply(http.StatusNoContent)

// Act

err := mocking.UpdateUser(1, &mocking.Information{

FirstName: "Grace",

LastName: "Hopper",

})

// Assert

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("unexpected error: %s", err)

}

}Testing with Gock

We wrote our first test with Gock, on a nominal case. Remind that you should test nominal cases, but also borderline cases and error cases.

Attention: be careful while using Gock with parallel tests, and read the documentation to keep independent tests.

Mock SQL

When you have pieces of code performing requests to a database, you can create unit tests and mock the SQL database thanks to a tool.

We will use go-sqlmock to make this possible.

go-sqlmock

func TestDatabaseQuery(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

db, mock, err := sqlmock.New() // db is a *sql.DB, mock is a sqlmock.SqlMock

mock.

// ExpectXXX

ExpectQuery("SELECT ...").

ExpectExec("UPDATE ...").

// WithXXX

WithArgs(...).

WithoutArgs().

// WillReturnXXX

WillReturnError(errors.New("...")).

WillDelayFor(5 * time.Second).

WillReturnRows(

sqlmock.NewRows([]string{"id", "name"}).

AddRow(1, "Grace")

)

// Act

user, err := GetUser(db, 1)

// Assert

}go-sqlmock

// Testing db.Query("SELECT * FROM products WHERE id = $1", 42)

func TestFindProduct(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

db, mock, err := sqlmock.New()

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("error while getting mock: %s", err)

}

mock.ExpectQuery(regexp.QuoteMeta("SELECT * FROM products WHERE id = $1")).

WithArgs(42).

WillReturnRows(

sqlmock.NewRows([]string{"id", "product_name", "price"}).

AddRow(42, "Computer", 899.99),

)

// Act

...

// Assert

...

}Test ListUsers

Write unit test with SQL mock for ListUsers function.

file/to/open.go$ go test -run TestListUsersFile to open:

Test your code:

unit/mocking/sql.go

unit/mocking/sql_test.goTestListUsers

func TestListUsers(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

db, mock, err := sqlmock.New()

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("error while getting mock: %s", err)

}

databaseService := mocking.NewDatabaseService(db)

mock.ExpectQuery("SELECT id, first_name, last_name FROM users").

WillReturnRows(

sqlmock.NewRows([]string{"id", "first_name", "last_name"}).

AddRow(1, "Grace", "Hopper"),

)

// Act

...

// Assert

...

}Mocks

Mocks (HTTP or SQL) are often seen as the easy way to go to test some part of your code.

But usually, while mocking, you are in fact mocking some dependencies you don't own.

Integration tests are often a better way to go!

"Don't mock what you don't own"

Test FindUserByID

Write unit tests with SQL mock for FindUserByID function.

Write two tests:

- Nominal case: TestFindUserByID

- Error case: TestFindUserByIDNoRows

file/to/open.go$ go test -run TestFindUserByID

$ go test -run TestFindUserByIDNoRowsFile to open:

Test your code:

unit/mocking/sql.go

unit/mocking/sql_test.goTestFindUserByID

...

mock.ExpectQuery(regexp.QuoteMeta("SELECT id, first_name, last_name FROM users WHERE id = $1")).

WithArgs(1).

WillReturnRows(

sqlmock.NewRows([]string{"id", "first_name", "last_name"}).

AddRow(1, "Grace", "Hopper"),

)

...TestFindUserByIDNoRows

...

mock.ExpectQuery(regexp.QuoteMeta("SELECT id, first_name, last_name FROM users WHERE id = $1")).

WithArgs(1).

WillReturnRows(sqlmock.NewRows([]string{"id", "first_name", "last_name"}))

...Using fake data

Using fake data

Sometimes, you have to generate random data for your tests.

Faker is a package providing function to generate fake data: https://github.com/bxcodec/faker

Many data types are provided: https://pkg.go.dev/github.com/bxcodec/faker/v4#section-documentation

Testify

Testify is a toolkit to write tests in Go.

It comes with three main features:

- Assert

- Require

- Suite

Testify assert

func TestSomething(t *testing.T) {

assert.Equal(t, 123, 123, "they should be equal")

assert.NotEqual(t, 123, 456, "they should not be equal")

assert.Nil(t, object)

assert.NoError(err)

...

}Provide helpers to make assertion easier.

Testify require

func TestSomething(t *testing.T) {

require.Equal(t, 123, 123, "they should be equal")

require.NotEqual(t, 123, 456, "they should not be equal")

require.Nil(t, object)

require.NoError(err)

...

}Same as assert, but with a FailNow.

Testify suite

The suite package provides functionality that you might be used to from more common object-oriented languages.

With it, you can build a testing suite as a struct, build setup/teardown methods and testing methods on your struct, and run them with 'go test' as per normal.

Testify suite

type TestSuite struct {

suite.Suite

}

func (t *TestSuite) TestFunction1() {}

func (t *TestSuite) TestFunction2() {}

func (t *TestSuite) SetupSuite() {}

func (t *TestSuite) TearDownSuite() {}

func (t *TestSuite) SetupTest() {}

func (t *TestSuite) TearDownTest() {}

func TestMain(t *testing.T) {

suite.Run(t, &TestSuite{})

}Execution order:

- SetupSuite

- SetupTest

- TestFunction1

- TearDownTest

- SetupTest

- TestFunction2

- TearDownTest

- TearDownSuite

Rewrite SQL tests with Testify

Let's rewrite SQL tests with Testify.

Documentation: https://pkg.go.dev/github.com/stretchr/testify/suite

Example: https://github.com/stretchr/testify?tab=readme-ov-file#suite-package

file/to/open.go$ go testFile to open:

Test your code:

unit/mocking/sql_testsuite_test.goSQL tests with testify suite

type TestDatabaseServiceSuite struct {

suite.Suite

database *sql.DB

databaseMock sqlmock.Sqlmock

service *mocking.DatabaseService

}

func (t *TestDatabaseServiceSuite) SetupSuite() {

var err error

t.database, t.databaseMock, err = sqlmock.New()

t.Require().NoError(err)

t.service = mocking.NewDatabaseService(t.database)

}

func (t *TestDatabaseServiceSuite) TearDownSuite() {}

func (t *TestDatabaseServiceSuite) SetupTest() {}

func (t *TestDatabaseServiceSuite) TearDownTest() {

t.Require().NoError(t.databaseMock.ExpectationsWereMet())

}SQL tests with testify: TestListUsers

func (t *TestDatabaseServiceSuite) TestListUsers() {

// Arrange

t.databaseMock.ExpectQuery("SELECT id, first_name, last_name FROM users").

WillReturnRows(

sqlmock.NewRows([]string{"id", "first_name", "last_name"}).

AddRow(1, "Grace", "Hopper"),

)

// Act

users, err := t.service.ListUsers()

// Assert

t.Require().NoError(err)

t.Require().Len(users, 1, "length should be one")

t.Require().Equal(users[0], &mocking.User{ID: 1, FirstName: "Grace", LastName: "Hopper"}, "they should be equal")

}SQL tests with testify: TestFindUserByID

func (t *TestDatabaseServiceSuite) TestFindUserByID() {

t.databaseMock.ExpectQuery(regexp.QuoteMeta("SELECT id, first_name, last_name FROM users WHERE id = $1")).

WithArgs(1).

WillReturnRows(

sqlmock.NewRows([]string{"id", "first_name", "last_name"}).

AddRow(1, "Grace", "Hopper"),

)

// Act

user, err := t.service.FindUserByID(1)

// Assert

t.Require().NoError(err)

t.Require().NotNil(user)

t.Require().Equal(user, &mocking.User{ID: 1, FirstName: "Grace", LastName: "Hopper"}, "they should be equal")

}SQL tests with testify: TestFindUserByIDNoRows

func (t *TestDatabaseServiceSuite) TestFindUserByIDNoRows() {

t.databaseMock.ExpectQuery(regexp.QuoteMeta("SELECT id, first_name, last_name FROM users WHERE id = $1")).

WithArgs(1).

WillReturnRows(sqlmock.NewRows([]string{"id", "first_name", "last_name"}))

// Act

user, err := t.service.FindUserByID(1)

// Assert

t.Require().ErrorIs(err, sql.ErrNoRows)

t.Require().Nil(user)

}SQL tests with testify: run your suite

func TestDatabaseService(t *testing.T) {

suite.Run(t, &TestDatabaseServiceSuite{})

}Testify

Testify will make your tests easier to write and read:

- by aggregating the Arrange section thanks to the Setup

- by aggregating part of the Assert section thanks to the TearDown

- by making the Assert part easier to write

Integration testing

Integration tests

You might have noticed that mocking can be a solution for some use cases, but it does not fit all of them.

Especially when it comes to mock database. Spoiler: it becomes harder to test a database while using an ORM, for example. Or a SDK to a HTTP API.

This is why we should rely on integration tests to properly test the behaviour of an external service, by using or spawning the external service during tests.

Build tags

Build Tags in Go is an identifier (in the form of a single line comment) added to the top level of your file, which tells the Go Compiler to what to do with the file during the build process.

Build tags are used during the go build process, but also during the go test one!

Build tags can then be used to properly separate your test files.

Using build tags

// +build integration

package sql

func TestSqlQuery(t *testing.T) {

...

}For example, you will be able to tag some files with a given tag, like integration. By default, go test command will ignore those files, unless you run go test -tags=integration.

$ go test -tags=integrationUsing build tags

By doing so, you will be able to run integration tests only on the proper environment where your external dependencies are started.

Integration tests should run on your CI/CD, with a staging or preproduction environment.

But you can also use some tools to start your dependencies directly from your tests!

Testcontainers

Testcontainers

Testcontainers is an open source framework for providing throwaway, lightweight instances of databases, message brokers, web browsers, or just about anything that can run in a Docker container.

Testcontainers

func TestWithRedis(t *testing.T) {

ctx := context.Background()

req := testcontainers.ContainerRequest{

Image: "redis:latest",

ExposedPorts: []string{"6379/tcp"},

WaitingFor: wait.ForLog("Ready to accept connections"),

}

redisC, err := testcontainers.GenericContainer(ctx, testcontainers.GenericContainerRequest{

ContainerRequest: req,

Started: true,

})

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Could not start redis: %s", err)

}

defer func() {

if err := redisC.Terminate(ctx); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Could not stop redis: %s", err)

}

}()

}Testing Database Service with testcontainers

Let's rewrite our unit tests with testcontainers so it's based on a PostgreSQL container instead of SQL mocks.

File to open:

solution/integration/sql/testdata/

solution/integration/sql/sql_test.goTestcontainers conclusion

Testcontainers can spawn any container from your code. You can write your own modules to make things easier, but it also comes with community modules you can use directly.

Be careful about keeping your tests independent!

Introduction to TDD

(bonus)

What's next?

- Learn how to use Test Driven Development: https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/test-driven-development/0321146530/

- Write unit tests for Echo: https://echo.labstack.com/docs/testing

- Mock Go interfaces:

- More about Test Double: https://medium.com/@matiasglessi/mock-stub-spy-and-other-test-doubles-a1869265ac47

- More about build tags: https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/customizing-go-binaries-with-build-tags

Thanks! Questions?

Test your code

By Nathan Castelein

Test your code

- 290