Title Text

Text

An Educational and Training Conference on DevOps

The event was called, "Achieve Agile Nirvana Through DevOps," and was held at the General Services Administration at 1800 F Street, NW, in Washington DC.

Approximately 100 guests attended from government and industry, and there was a panel of five speakers and moderators. For three hours, the panel members addressed questions from the audience and from one another.

The purpose of the event was to tackle the tough issues—including those raised by naysayers and skeptics—and provide progressive answers.

The American Council for Technology-Industry Advisory Council (ACT-IAC) is a non-profit educational organization established to improve government through the efficient and innovative application of information technology. The American Council for Technology (ACT) was founded in 1979. In 1989, they established the Industry Advisory Council (IAC) to bring business and government executives together to collaborate on IT issues of interest to the Government. The new partnership was called ACT-IAC.

This unique, public-private partnership is dedicated to helping Government use technology to serve the public. The organization communicates, educates, informs, collaborates, and promotes the profession of public IT management. ACT-IAC offers a wide range of programs to achieve these aims.

ACT-IAC welcomes the participation of all public and private organizations committed to improving the delivery of public services through the effective and efficient use of IT. For membership and other information, visit the ACT-IAC website.

ACT-IAC

GSA 18F

GSA 18F is a small group within the General Services Administration (GSA) focused on user-centric digital services and the interaction between government and the people and businesses it serves. This newly formed organization encompasses the Presidential Innovation Fellows program and an in-house digital delivery team to help other agencies deliver on their mission.

Speakers

Noah Kunin: Chief of Infrastructure at the General Services Administration (GSA).

Kaitlin Devine: Director of Engineering Services for 18F. Previously at the Sunlight Foundation.

Mark Schwartz: CIO of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), champion of agile/DevOps.

Lisa Gelobter: Chief Digital Service Officer at the U.S. Department of Education (DoEd), formerly at Black Entertainment Television (BET) where she ran Digital Product, Technology & Operations.

Moderators

Greg Godbout: CTO of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Formerly Executive Director and co-Founder at 18F.

Jared Townshend: Senior Manager at Deloitte.

David Patton: Federal Practice Director at C.C. Pace Systems, Inc.

General topics of discussion were:

-

How IT Development Operations (DevOps) can help improve speed-to-market.

-

DevOp challenges and how business and federal agencies are addressing them.

-

Good first steps to take on the journey towards full DevOps realization.

-

How to break down the opposition to adopting DevOps.

-

DevOps inspiration—people and organizations.

-

How to integrate DevOps into the ever-present compliance functions.

- About the ACT-IAC Conference #1

- About DevOps #7

- General Topics of Discussion #2

- DevOps Basics #14

- Release Management #29

- About the Presentation #4

- Questions Raised #5

- Security & Risk #31

- Inspiration & Innovation #38

- Where Do We Go From Here? #40

This presentation is a summary of the ACT-IAC "Achieve Agile Nirvana Through DevOps!" educational and training conference.

NCI's Agile Technology Sector volunteered the services of Senior Vice President and General Manager Lawrence Fitzpatrick and Corporate Writer Heidi Heider, who wrote and prepared this presentation for ACT-IAC.

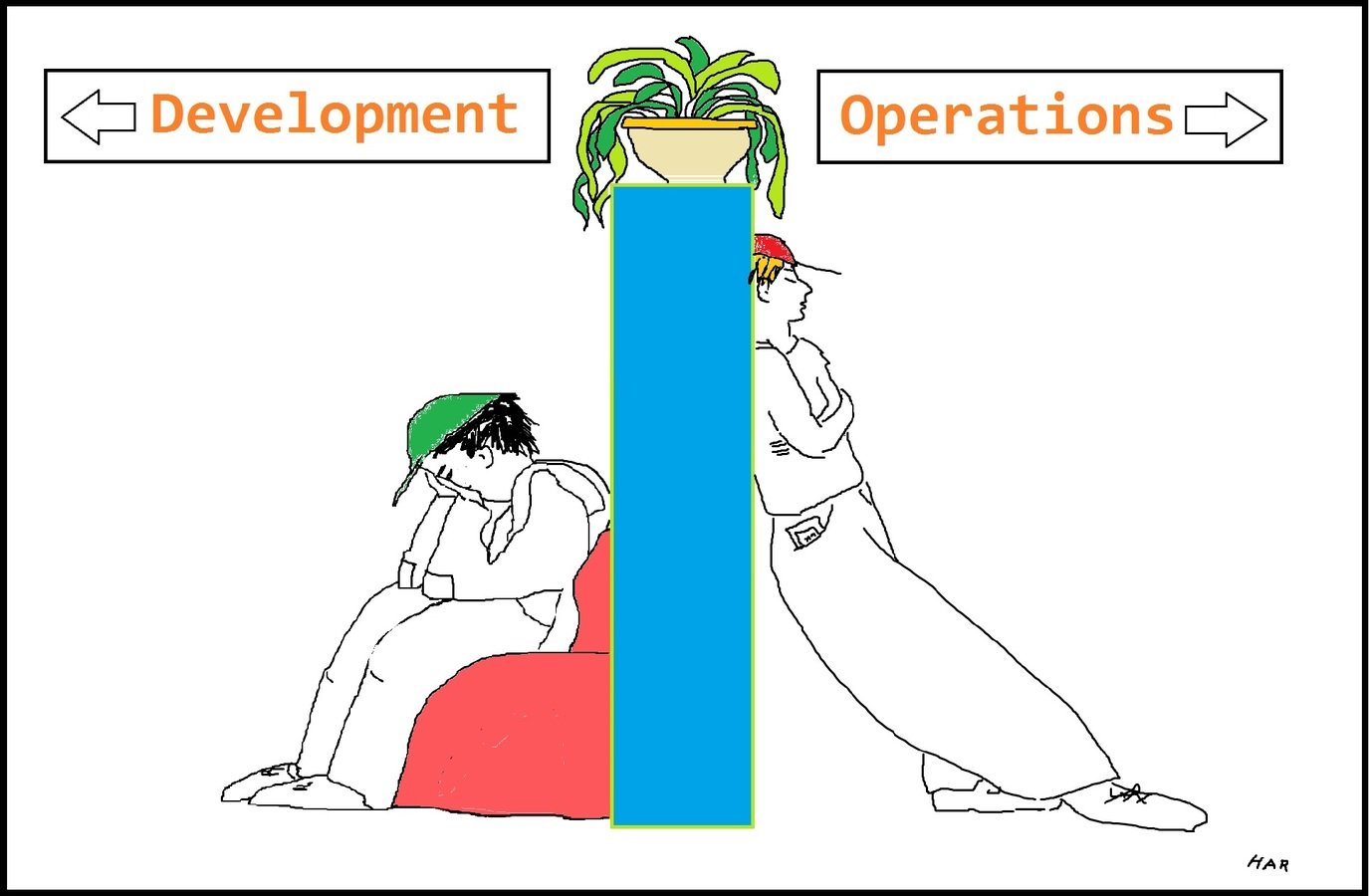

The panel discussion has been organized by subject, and contains additional comments and explanations to clarify salient points and make the conversation accessible to a wider audience. The authors have enhanced the presentation with sidebars, graphics, and original drawings by H.A. Raebeck.

-

How do I know this isn’t another buzzword?

-

How do you apply DevOps to legacy systems?

-

How do you unify DevOps, software engineering, and release engineering?

-

Does DevOps mean I have to do agile?

-

How do you go from a silo culture to a methodology that is the antithesis of that culture; where do I start?

-

Can you acquire DevOps?

-

What is the first step you take to make sure a cross-functional team works together?

-

Is DevOps being accepted by organizations?

-

How does DevOps change how you think about change control boards (CCBs)?

-

Why should those crazy developers have more control over release?

-

How do you apply devops to legacy systems development?

-

How do you work with DevOps and the security world?

-

Is there still a real need to have policies that contain risk aversion?

-

What models have been inspirational?

-

What are your thoughts on driving innovation?

-

How does DevOps hurt or help security?

-

How do you deal with all of the policy hurdles in the IT environment?

-

What information should be public and what should stay private?

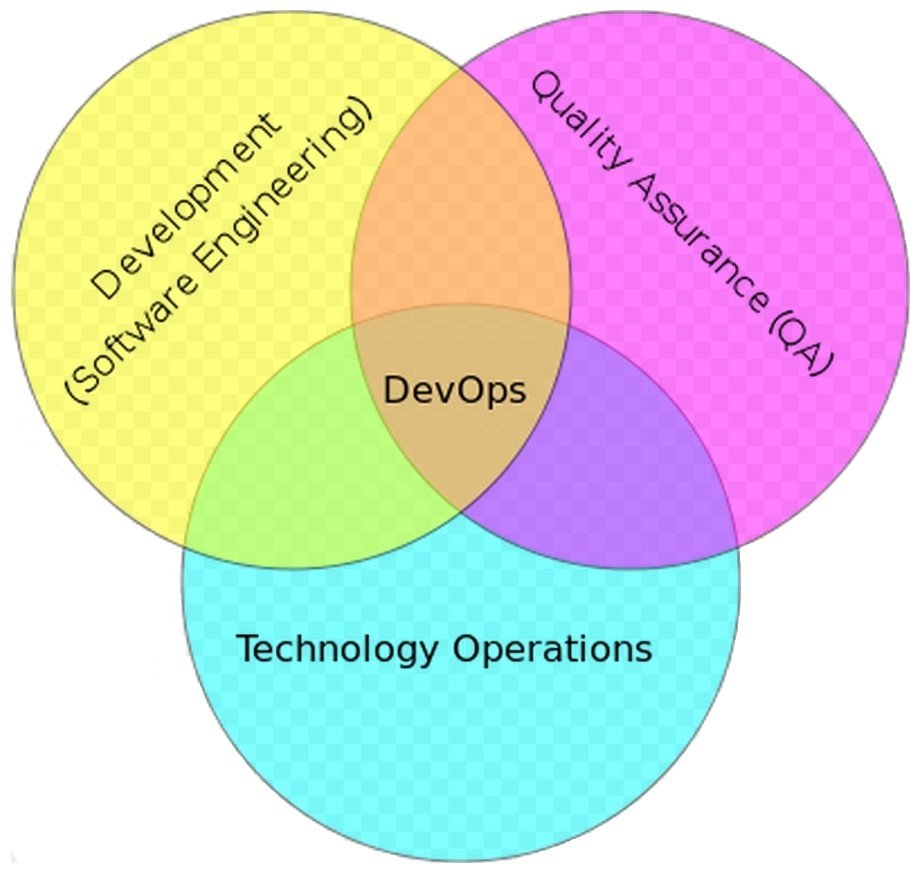

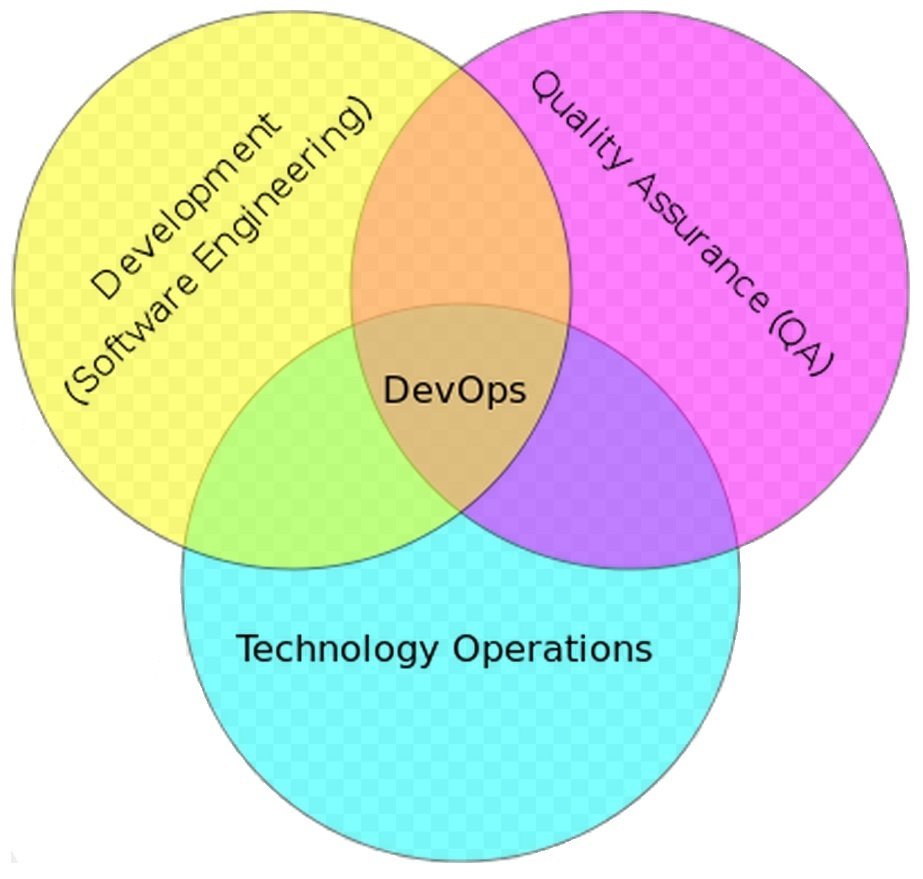

DevOps is a set of IT principles and practices that aim to reduce the cycle time between dev and ops (development and operations) and improve quality.

To do this, you have to include all of the related IT functions, such as security operations, etc. Ultimately, you want rapid, short feedback cycles from production. This is a standard way of operating; everyone should be doing this.

For example, one purpose of 18F is to improve the way government builds application services; making them better, faster, and more frequent; and this wouldn’t be possible without DevOps.

DevOps is more than a buzzword. It is here to stay.

DevOps is something that we should always have been doing.

Once people see it in action, it will stick.

DevOps is much more than configuration management (CM). CM—the set of processes and tools that control the source code of the software system—can be the seed from which DevOps grows, but it is not sufficient on its own.

DevOps addresses build (turning the source code into executables); automated testing (unit, system, smoke); compliance (security, 508, privacy, etc.); environment management; deployment—pushing code from one environment to another—dev to test, test to acceptance test (AT), AT to production, etc.; and service monitoring (monitoring the apps and platforms in production).

Leadership matters. To apply DevOps successfully, you need smart folks at the helm who know what they’re doing.

In order to reduce cycle time significantly, compliance people (involved with FISAM security, Privacy Act, etc.) need to engage with the DevOps team and they need to do this early in the process. Do not wait to check compliance until right before releasing to production. Have the compliance staff test and evaluate alongside and in parallel with the dev and ops teams, from the git-go.

Full transparency of all relevant artifacts, at all times, to all stakeholders, makes a big difference in getting everyone on board and it raises productivity levels.

Don't let the tools stand in the way of productivity. If your standard tools are not getting the job done, throw them in the trash. Adopt the tools that help you get going.

DevOps promotes continual improvement. Examine impediments and don't be afraid to jettison baggage that's slowing down the team.

Recommended reading: The Phoenix Project

- Always make the work accessible to everyone.

- Create systems that allow work to continually move forward and change.

-

Choose a distributed version control system and put everything in it, now.

- If tools are hurting your organization, get rid of them. (Trash your office apps if it will improve products and/or processes.)

The impact of DevOps hasn’t fully been felt because it’s still new. In many cases, it has reduced stress over things that go to production, but people involved have to adjust to operating at a faster pace.

Customers, on the other hand, will easily accept DevOps when they get products and services faster. And if everything is running smoothly, people rarely question why.

You can use good technical practices and good people practices, and agility is not necessarily part of that. But you should at least be using agile for your highest value requirements.

The team that’s creating a solution should be small and agile helps you to get higher value.

DevOps cuts out all the waste; and we test a lot so that we don’t have another healthcare.gov. We recommend using the same techniques as Google, Amazon, etc., and they are using agile along with DevOps.

Also see: Agile and Compliance

Back to: Managing Risk

The massive scale internet companies—Google, Facebook, Netflix, Amazon—have pioneered the application of agile practices in the operations world.

Concepts like continuous delivery, A/B testing, and release engineering have coalesced into highly disciplined functions.

For insights into the degree of discipline and automation, watch Chuck Rossi's video (of Facebook) on release engineering or talks on continuous delivery by Diane Marsh (of Netflix).

To make sure a cross-functional team works together:

- Start small and show that the process has worked really well.

- Identify a line of business that gets little attention from IT and do something awesome for them by promising agile [“work with the willing & needy”].

- Leverage that success to sell to the mainstream. (Sell your strategy to leaders of business units.)

- Then take the big jump by selling to directors and higher up.

Stay in touch with the teams.

Get involved in your vendor’s activities.

-

Testing should be built into your process from the jump.

- Work with security early.

- By changing priorities in a backlog, you can start a large project immediately.

- Talk to stakeholders and speak in their voice. Don't make them do all the work.

- Let the stakeholders know that this is about making them successful.

The trick is finding good product management.

The benefit of being a product owner is you have complete transparency; when you outsource that you lose it.

As an agency, you should act as your own system integrator. This helps to form a team mentality. It keeps federal staff involved and invested in moving things forward; the more you do it, the easier it becomes. This idea of government being its own integrator is an important thing.

The trend for government contracting has been to do FFP (firm-fixed-priced contracts), but now we're coming back to T&M (time and materials), which makes more sense. It’s hard for the client to grasp that building and managing IT systems is not like buying a car.

Recommended reading: Amazon's Approach to Product Management

The trend to firm-fixed-price (FFP) contracting was spurred by the idea that you could ship risk to the contractor. What they didn't understand was that for most software it's impossible to spec it well enough to get realistic bids; to do so requires outstanding collaborative product management from the government.

Now, people are recognizing that, indeed, time and materials (T&M) contracting is a much more efficient way to get the right resources, directed by good product management—and it leads to better/cheaper products.

It doesn’t work well to “acquire” DevOps in isolation, because it is a complex set of people, hardware, and software that cuts across traditional organizational silos.

The danger is that you will push all the work onto the contractor you have hired, and this will create pressure that can lead to failure.

It’s important to get all stakeholders, from apps to ops to management to customers, engaged, involved, and on board.

It makes no sense to write a contract for a team of people to implement DevOps as a standalone group without acknowledging that key collaborations will be required with many other functions. DevOps cannot succeed on it’s own; it is part of a larger organism.

You cannot adequately test software if you’re keeping developers out of production environments.

Testing has to address environment incompatibility. The differences between environments (dev, test. prod) must be covered by the testing protocols.

The scary part about giving developers more access is that when you give them more power you give them more responsibility.

Can they and will they accept the new responsibilities?

In his article, "High Performance Evolution: Going Agile Throughout the IT Organization," published in the Cutter Consortium, 30 December 2014

To regression-test a large complicated legacy system without automated regression testing is very expensive. At some companies, test teams can be three times larger than dev teams. [That is a 3:1 ratio; and while there is no perfect number of testers to developers, a ratio greater than 1:3 is unusual.]

Much of the DevOps focus is on new development, but many legacy systems were constructed without the benefit of a DevOps mindset.

So, how do you apply DevOps to legacy systems?

Testing automation is lacking for legacy systems. So it's harder to make changes quickly and deploy them when you don't have an automated way to tell whether the system works after you've made changes. This is why regression testing can be lengthy and time consuming. However, over time, for some systems, there may be some remediations for the automated testing deficits. [In the meantime, there are other parts of the problem, such as provisioning and deployment that can be successfully addressed using DevOps and automation.]

Recommended reading: Working Effectively with Legacy Code

Back to: Inspiration & Innovation

Full transparency is good, but there are times when you can't share everything.

Teams should determine, up front, which data should be shared and which data is not appropriate for public viewing.

Also see: Transparency vs. Information Protection

In his article, "High Performance Evolution: Going Agile Throughout the IT Organization," published in the Cutter Consortium, 30 December 2014

Regular, accurate, and salient communication is essential to collaboration, and collaboration is critical to both changing an organization and running projects effectively. By "salient communication," we mean communication that focuses on outcomes — on what matters. But transparency is more than communication. Transparency introduces an intention to be open and is a fundamental shift in thinking that veers away from viewing communication as a control activity. Working in a transparent environment encourages people to communicate regularly and, of equal importance, to think carefully about the information they disseminate.

"Regular" communication means that project information must be readily available to anyone who needs it, 24/7. Transparency should allow peers, management, and customers to watch the project in real time as it progresses, using the same lens as the team members themselves.

Change control becomes a periodic auditing process to make sure that you’re still following discipline. The benefit of a change control board (CCB) is that it tends to ask for evidence that you've tested thoroughly, which makes it critical that you test well, prior to deployment.

A change control process can satisfy audit requirements if the CCB looks at real evidence [like metrics from test results] to determine if software is ready to be released [not just artifacts created to satisfy the CCB].

But often the CCB isn’t very effective because they ask for irrelevant documentation to prove viability. A more effective change process would require real artifacts and actual evidence, and so, the change control process needs to be changed.

The change control process might not have to be a board—it could become an independent validation activity for deployment decisions.

One function of DevOps is to streamline the move of code to production. Change control boards (CCBs) are concerned with making sure that what goes to prodution should go to production. So DevOps practices—automation and metrics—can aid the change activities.

Technical debt can be a problem if you fail to build or fix something that is required.

But it can be okay not to implement certain features, as long as you're doing it intentionally, in order to build "the minimum viable product."

In other words, intentionally incurring technical debt can be a good way to get minimally sufficient products into the marketplace quickly.

The government tends to deal with technical debt by planning a massive swap of old versus new, usually involving a large legacy modernization project, which is high risk and very costly.

In many cases, a smarter alternative is to remove technical debt incrementally, in small pieces.

Remove Technical Debt Incrementally

Back to: Inspiration & Innovation

Stay in touch with the teams.

When an environment has one contractor/vendor for ops and another on the dev side; one or the other can start feeling paranoid. [Their missions are often at cross purposes, so there is a natural divide—one to safeguard stability—the other to improve capability.]

Is it wise to have one vendor handle the dev side and the ops side?

But when accountability is properly aligned, it doesn’t matter if there are multiple vendors or one vendor. It’s about skill set.

Get involved in your vendor’s activities.

Being your own systems integrator helps to mitigate the tension and unify the goals.

Organizations often struggle to do releases. Releases can be inconsistent and often are unsuccessful. Some of the challenges faced:

- How fast can you push from one environment to the next, including production?

- How reliably and consistently can you push from one environment to the next?

- How stable is the product that you pushed? [One common source of problems is multiple environments with unique configurations, which cause the software to behave differently.]

- Once diagnosed, how quickly can you push a corrected version of the software; or make an environment modification to deal with the issue (which may involve adding resources, etc.)?

- When you find a problem in an environment, how quickly can you diagnose the problem? Can you get the information you need from logs, etc.?

[DevOps addresses these points by increasing the speed with which you can release software, while increasing the certainty that the release activity actually works as intended. Double win.]

DevOps aims to unify software engineering and release engineering. You can do this by adding better tools to the broader toolset to improve processes and performance.

Traditionally, deployment takes forever. But by rotating developers through the DevOps team they can “walk a mile in the other man’s shoes,” and this gives the developers greater understanding (and empathy) and makes the entire process, (inlcuding release) smoother, faster, and better.

- If you’re not including security in the DevOps process, you’re not doing DevOps.

- Monitor production—and if you find something—the time required to repair it is so fast that it reduces risk. [DevOps automation allows the teams to go through the cycle of software fix, build, regression test, and deploy very quickly—tens or hundreds of times faster than the all-to-common manual practices.]

- DevOps will increase security, if only because of automated test pipelines, static code analysis for every build, and the use of the same diagnostics continually.

- You have to work with security early.

- The issue is how to convince the policy people that DevOps is safe.

- Security policies can present an obstacle. Instead of laying blame, offer to work together to make the policies better.

- When it comes to security policies, always examine each policy and ask why. There are often good reasons for the policies, but you have to understand what they are.

- You need to treat others with respect and not dismiss their objectives or requirements out of hand. Find common ground.

- Recognize that oversight is about reducing risk, and propose that your technique reduces risk as much as possible. Also, you can stay a bit below the radar by continuing to make small incremental changes.

Back to: Managing Risk

One function of DevOps is to streamline the move of code to production. Change control boards (CCBs) are concerned with making sure that what goes to prodution should go to production. So DevOps practices—automation and metrics—can aid the change activities.

-

Communicate your understanding of their goal before you suggest new procedures to achieve it.

-

Then demonstrate how the new approach will meet or exceed their expectations, even if the means of arriving there is not what they expected or envisioned.

-

When all else fails, use the burning platforms all around you. Point out that, “94% of federal IT projects fail.” Use this information to turn things around. Explain that their policies were in force during all of the failures, so the policies need to be revised.

- The policy folks almost always want to state what people should do or should not do to protect the organization, and since they see this as their job, it’s not surprising. But they usually have a hard time describing the actual outcomes they want to achieve. Often the route they suggest is not the most direct path to their desired result, and this is your leverage.

- Use a sales approach. [Emphasize that you agree with the policy makers and enforcers about the fact that security requirements must be met. Show them that you can better meet their needs and achieve the objectives of the organization by doing things in a new way.]

- Recognize that oversight is about reducing risk, and propose that your technique reduces risk as much as possible. Also, you can stay a bit below the radar by continuing to make small incremental changes.

- All DevOps information should be kept in open repositories for sharing, and that includes security documents.

- Try to be proactive and outline the things up front that should not be made public.

- You need to conduct your analysis up front to identify this information and determine how it should be protected. But use restraint—try not to achieve your security goals by relying on "security through obscurity" [a well known tactic, akin to the intellectual property model known as "trade secret"].

- If information needs to be protected, be open and straightforward about what and why. There should be no hazy areas.

Also see: Fostering Transparency

Most policy is about risk aversion. You need to deal with risk mitigation instead.

Using agile/interative prioritization requires the government, or the customer, to constantly make decisions about what’s next so that vendors only work on what is needed “now.” When that mission is accomplished, a new set of priorities is identified. More work up front results in much less waste down the line and lower costs across the board.

Identify the risks inherent in the legacy approaches as well as any risks posed by new methods or technologies.

Many studies have shown that most of the features built under the waterfall model of the SDLC are never used. (The Standish group study found that two thirds of features built are rarely if ever used.)

This means two thirds of the budget was thrown away. And this is due to the “Big Requirements Up Front” (waterfall) development model. This model says, “Tell me all the things you want and I'll build them for you.” The agile model says, “I'll build your most important requirements in the next month. Then we’ll repeat the process.”

People frequently hire an outside integrator, believing that it is less risky to make just one person accountable (have "one neck to choke"), but often it increases risk. And this is because it is usually less risky to place key decision-making authority in the hands of someone more closely aligned to the organization’s mission.

It's almost always safer to do less than more. The people closest to the mission—the customer—should be trained to prioritize. When work gets too complicated, sometimes the only viable action is to simplify.

The government, or the customer, is in the best position to correct problems (reduce scope, reprioritize), and this minimizes the biggest risks.

Perhaps the risk aversion that is baked into security policy is not a real need. There is a great deal of oversight in government. The traditional environment tends to be low trust and high criticism, so risk aversion is a natural response. Avoiding risk is now built in to the program, but “at all costs” increases costs, as well as complexity. In the end, it can cost more to avoid all risk than to tolerate a certain amount of “controlled risk.” [Excessive oversight also squelches innovation.]

There is an organization that embeds security engineers in every agile team and this has been so successful that the entire security and compliance function has become agile. They integrate their security requirements as “stories” on the backlog and execute them as part of the two week sprints; anyone can do this.

Also see: Managing Policy Hurdles

Agile and Compliance

Back to: Does DevOps Require Agile?

To innovate, create a sandbox where people can experiment and fail, and this will reduce the cost of actual failure. DevOps is perfect for this.

[Because DevOps lets you build, deploy, and test so efficiently and quickly; you can run this cycle with really small changes, which may not even be noticed. This inherently reduces risk of failure and allows for experimentation.]

The Twelve Factor App and Heroku. These principles involve keeping your configuration coupled or decoupled; testing; rapid deployment.

Moving from full builds to packages; Amazon.

Inspiring DevOps Models

Amazon's transformation to service oriented architecture (SOA). They moved away from big monolithic apps to everything as a service. Now, they can enhance, fix, and deploy changes to pieces much easier than to the huge apps they had previously. The new major apps are just assemblies of SOA parts.

He defines legacy as not having automated testing. Lack of automated tests is a barrier to getting DevOps into legacy systems.

You must move incrementally. That means having good test, build, deploy.

Also see: Enterprise DevOps

Jez Humble, Netflix; Copy their playbook; they’re innovating with corporate culture practices as well as with DevOps.

Legacy systems need to be approached in a way that injects loose coupling—slowly teasing apart the components of the systems. When replacing legacy systems, you can’t risk losing functionality as you replace segments, so you can't tear out pieces.

Michael Feathers book on legacy code.

Inspiring DevOps Models

We don't have to invent this stuff, we just need to borrow what's been learned by innovative companies ahead of us. When asked about innovation, Doug Cutting, the creator of Hadoop and Lucene—two popular open source plafforms— said that “Google is living a few years in the future and sending the rest of us messages.”

Don't we owe it to our customers, and to our mission, to listen?

Based on this discussion, we can say that:

- DevOps can cover a lot of ground.

- It still has its challenges, but solutions to each problem abound and many companies and organizations are already experiencing great benefits.

- It’s compatible with other popular process improvements frameworks.

- DevOps is not a fad but is here to stay. It’s not a question of whether you should get onboard the DevOps train, but when.

- Resistance is more likley to come from staff members and vendors who may not want to take on more responsibility or work faster (or erronesously believe they are giving up control), than it is from customers who are getting better, faster service.

ACT-IAC DevOps Conference

By NCI Agile Technology Sector

ACT-IAC DevOps Conference

ACT-IAC DevOps Conference

- 1,673